Abstract

Ligand exchange reactions are widely used for imparting new functionality on or integrating nanoparticles into devices. Thiolate - for - thiolate ligand exchange in monolayer protected gold nanoclusters has been used for over a decade; however, a firm structural basis of this reaction has been lacking. Herein, we present the first single-crystal X-ray structure of a partially exchanged Au102(p-MBA)40(p-BBT)4 (p-MBA = para-mercaptobenzoic acid, p-BBT = para-bromobenzene thiol) with p-BBT as the incoming ligand. The crystal structure shows that 2 of the 22 symmetry-unique p-MBA ligand sites are partially exchanged to p-BBT under the initial fast kinetics in a 5 minute time scale exchange reaction. Each of these ligand-binding sites is bonded to a different solvent exposed Au atom, suggesting an associative mechanism for the initial ligand exchange. Density functional theory calculations modeling both thiol and thiolate incoming ligands postulate a mechanistic pathway for thiol based ligand exchange. The discrete modification of a small set of ligand binding sites suggests Au102(p-MBA)44 as a powerful platform for surface chemical engineering.

Keywords: Ligand exchange, gold nanoparticles, gold nanoclusters

INTRODUCTION

Surface chemical modification of nanoparticles is of fundamental importance in their assembly,1,2 implementation in biology3 and medicine,4 and also affects their electronic5,6 and optical7 properties. Ligand exchange reactions are a primary means for surface modification of metal8 and semiconductor9 nanoclusters as well as nanocrystals. Such reactions generally proceed as a stoichiometric 1:1 replacement of metal nanocluster bound ligands for freely solvated ligands. For the gold thiolated monolayer protected nanocluster (AuMPC) class of nanoparticles, ligand exchange is usually determined as proceeding by an associative (SN2-like) mechanism.10–15 Traditionally, AuMPCs have been understood as consisting of high-symmetry gold cores of truncated Oh, truncated Dh or full Ih geometry16–19 with organothiolate ligands bonded to vertex, edge and face sites. These distinct sites have been postulated to account for three ligand exchange environments and has been observed10 to be independent of the nanocluster core size.15 However, recent single crystal X-ray structures of Au25(SR)18, Au38(SR)24 and Au102(SR)4420–23 show that while AuMPC core Au(0) atoms conform to high symmetry (Ih or D5h), the surface layer of these nanoclusters imposes lower overall symmetries (C2, C3) due to the surface-covalent Au-S interaction, with the outermost Au(I) atoms bridging (μ) between SR in moieties.

The nanocluster of the present study, Au102(SR)44, is composed of 79 Au(0) core atoms in D5h symmetry with 23 formally Au(I) atoms held in RS(Au(I)SR)x (x=1, staple or x=2, hemiring) structural motifs on the surface,24 imposing C2 symmetry on the entire nanocluster. As a result of the C2 symmetry, the Au102(SR)44 nanocluster contains 22 symmetrically unique ligands within its crystallographic asymmetric unit. Because of the surprisingly low symmetry and unpredicted surface structure of these nanoclusters, it has been unclear how to reconcile structural data with multiple ligand exchange environments, and the structural mechanism of ligand exchange has been obscure.

To determine the structural basis for ligand exchange, we endeavored to determine which of the 22 symmetrically unique ligands of Au102(p-MBA)44 are most readily exchanged. To accomplish this, we solved X-ray crystal structures of single crystals containing partially ligand-exchanged Au102(p-MBA)44 nanoclusters. We used p-bromobenzene thiol (p-BBT) as the incoming ligand and probed the initial fast (time scale 5 min) ligand exchange reactions, which restricts the reaction to take place only at the most kinetically favorable exchange sites. Our results give the first unambiguous structural picture of the widely used thiolate place-exchange reaction on a gold nanocluster. The experimental results underpin a computational DFT study on energetics, reaction intermediates and pertinent transition states.

Our results suggest the possibility of targeting discrete ligand positions for exchange in a manner reminiscent of site directed mutagenesis of proteins, which are of similar size and topological complexity as Au102(p-MBA)44.

METHODS

Materials

Unless specified, reagents were sourced from Fisher Scientific or Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Tetrachloroauric (III) acid trihydrate (HAuCl4·3H2O, 99.99%) was received from Alfa Aesar and p-mercaptobenzoic acid (>95%) from TCI America. Nanopure H2O was purified to a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ-cm using a Barnstead NANOpure water system.

Au102(P-MBA)44 Synthesis

The AuMPCs used in this study were synthesized by modifications of a previously published method.25 HAuCl4·3H2O (0.209 g, 0.50 mmol, a non-metal spatula should be used to weigh out HAuCl4·3H2O) was dissolved in nanopure H2O (19.0 mL, 0.028 M based on Au) in a 50 mL conical. In a separate 50 mL conical, p-mercaptobenzoic acid (0.292 g, 1.89 mmol) was dissolved in a solution of nanopure H2O (18.43 mL) and 10 M NaOH (0.57 mL, 5.70 mmol). The resulting p-mercaptobenzoic acid/NaOH solution should be 0.10 M based on p-mercaptobenzoic acid and 0.30 M based on NaOH. A 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask was equipped with a stir bar and nanopure H2O (51.5 mL). In three separate beakers the following solutions were dispensed: a) 0.028 M HAuCl4 solution (17.8 mL, 0.5 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), b) 0.10 M p-mercaptobenzoic acid/0.30 M NaOH (15.5 mL, 1.5 mmol, 3.0 equiv. of p-mercaptobenzoic acid and 5.7 mmol, 11.4 equiv. of NaOH) solution, and c) MeOH (75 mL). Under stirring, the HAuCl4 solution was poured into the 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing H2O, immediately followed by the addition of the p-mercaptobenzoic acid/NaOH solution, the solution then turned from yellow to orange. MeOH was then added immediately afterward and the reactants were allowed to stir at room temperature for 1 h. During this time, the reaction turned from dark orange to light orange. After 1 hour, pulverized solid NaBH4 (20.8 mg, 0.55 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) was added to the reaction and it was allowed to stir at room temperature for 17 h. The reaction turned black upon addition of solid NaBH4. The reaction was then transferred to a 1000 mL Erlenmeyer flask and precipitated with the addition of MeOH (750 – 850 mL) and 5 M NH4OAc (35 – 45 mL). The reaction was then split into twenty 50 mL conicals and centrifuged at 4 ºC for 10 min at 4,000 rpm. The supernatants were decanted and the conicals were inverted on a paper towel to drain the remaining liquid, then the pellets were then allowed to air dry for 1 hour. The precipitate in each conical was then dissolved in 50 – 150 μL of 2 M NH4OAc and the black solution was combined into four 50 mL conicals. The residual material in the conicals was washed with 100 – 300 μL H2O and then combined with the previously dissolved nanoclusters. MeOH was then added until the total volume in each conical was 40 – 48 mL and the conicals were centrifuged again at 4 ºC, 4,000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was removed and the precipitates were dried in vacuo at room temperature for at least 2 h. The nanoclusters were stored as a solid at −20 ºC or resuspended in nanopure H2O. Gel electrophoresis visualization was done with a 20% polyacrylamide gel (19:1, acrylamide : bisacrylamide) at 110 V for 2 h.

Ligand Exchange

The ligand place exchange reaction was carried out as follows: p-bromobenzene thiol (p-BBT) was dissolved in THF at a working 3X stock concentration of 1.34 mg/mL (7.09 mM). Au102(p-MBA)44 (10 μL, 849 μM, 1.02 × 10−2 μmol) was transferred to a 1.5 mL tube, then 5 μL of the p-BBT stock solution (2:1 feed ratio of incoming thiol:gold = 2:44 feed ratio of incoming thiol:outgoing thiol) was added and the solution was vortexed for exactly 5 minutes before being quenched with 100 μL of isopropanol and 5 μL of 5 M NH4OAc. The solution pH was not explicitly controlled or measured in this reaction due to the impracticality of measuring pH for the small volume of reaction, and the desire to minimize the number of components in the reaction, knowing that both thiol and thiolate forms of sulfur are capable of exchange. The 1.5 mL tube was then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at rt. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended and washed in 10 μL of a 1:1 solution of nanopure H2O and THF to remove any remaining free thiol from solution. The solution was then precipitated again with the addition of 100 μL isopropanol and 5 μL 5 M NH4OAc, then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was dried in vacuo. The pellet was then resuspended in 10 μL nanopure H2O and allowed to crystallize in hanging drop well plates with the original mother liquor solution in which Au102(p-MBA)44 was crystallized23 (0.3 M NaCl, 0.1 M NaOAc, 40% MeOH, pH 2.5) over a period of 3 – 7 days. Once X-ray quality single crystals had formed, they were mounted onto nylon loops in a working mounting solution of 40 μL MeOH, 40 μL mother liquor and 15 μL 2-methyl-1,3-propanediol (MPD) as a cryoprotectant. Crystals were flash frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen prior to data collection.

Single Crystal Data Collection

Crystallographic data was collected on Beamline 4.2.2 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab Advanced Light Source. Typical wavelength was 0.827 Å. Data was collected to at least 1.5 Å (usually to 1.2 Å) resolution for both ligand exchanged and control crystals. Approximately 250 ligand exchanged crystals were screened for initial diffraction. Of these, 10 were screened and 7 crystals could be confirmed by X-ray fluorescence measurements to contain Br. A total of 10 crystals resulting from ligand exchanged products were judged sufficient for complete data collection. Of those 10 crystals, 2 were confirmed to have both Br fluorescence and suitable diffraction quality to complete crystallographic refinement to locate the positions of Br.

Single Crystal Data Processing

The two crystals with adequate data for processing gave quantitatively similar results, where we observed Br density attributed to ligand exchange in the PMBA2 and PMBA3 positions. For comparison, four crystals, which were not exchanged, were subjected to the same refinement strategy, where Br failed to refine into any position. The difficulty in obtaining high quality diffraction on heterogeneous crystals comprised of large liganded metal nanoclusters is reminiscent of the experiences reported by others.26 Data was reduced and indexed with XDS27 and XPREP28. Static Substitutional Refinement was carried out by attempting refinement of Br atoms in place of COOH groups for all 22 ligand positions in both control and experimental crystals. This was followed by anisotropic refinement of Br in four of the ligand positions to fully eliminate all but two locations in the exchange position and none in the wild type crystals (Table 1). Final refinement statistics from SHELX-9728 for the best ligand exchange crystal were R1 = 0.0840, R1(Free) = 0.1830 for 5512 reflections, R1 = 0.1420 and R1(Free) = 0.2459 for all 9650 reflections.

Table 1.

Summary of crystallographic data for Au102(p-MBA)x(p-BBT)y single-crystals.

| Ligand Exchange | Wild Type | |

|---|---|---|

| Location for data collection | ALS BL 4.2.2 | SSRL BL 11-1 |

| Symmetry Group | C2/c | C2/c |

| Unit cell dimensions | 30.33 Å × 57.05 Å × 38.18 Å | 30.40 Å × 58.18 Å × 37.91 Å |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.5 Å | 1.5 Å |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.827Å | 0.979 Å |

| Number of unique reflections | 9,334 | 9,234 |

| Completeness (%)* | 95.8% (92.9%) | 95.5% (94.1%) |

| <I/σI>* | 9.3 (2.55) | 21.34 (12.49) |

| Rsym‡ (%)* | 11.9% (50.0%) | 7.28% (16.89%) |

| § R (%)* | 8.40% (14.72%) | 8.01% (9.14%) |

| Free R¶ (%)* | 18.30% (24.59%) | 9.98% (11.22%) |

| GooF | 1.08 | 1.037 |

Number in parentheses represents the value for highest resolution shell

Rsym = ΣΣ|Ij - <I>|ΣΣj|Ij|

Free R calculated from 5% of reflections chosen at random

Computational Methods

For the computational modeling of ligand exchange in the Au102(SR)44 nanocluster, we used the density-functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the real-space code-package GPAW29,30 and PBE31 as the exchange-correlation functional. For computational reasons we replaced the p-MBA ligands with simple SH groups in most of our calculations and used methane thiolate as the model for the incoming ligand. For completeness, reaction energies were also estimated using true p-BBT/p-MBA ligands. In structure optimization we used 0.2 Å grid spacing and 0.05 eV/Å convergence criterion for the maximum forces acting on atoms in nanoclusters with SCH3/SH ligands and 0.1 eV/Å criterion for the nanoclusters with p-BBT/p-MBA ligands. The starting configuration for each step was taken from the optimized geometry of the previous step. The GPAW setups for Au include scalar-relativistic corrections.

Reaction paths for the ligand-exchange (shown in Figure 3) were solved using constrained structural optimization with a fully dynamic system, i.e., no fixed atoms. As a reaction coordinate we used, in the first part, the distance from the sulfur atom of the incoming thiol/thiolate to the gold atom of the active staple, and in the second part the distance from the sulfur atom of the outgoing thiol/thiolate to the core Au-atom binding site of the staple. The above-mentioned S-Au distances were gradually varied and were then fixed for the structural optimization of each step of the reaction. Additional calculations on plausible reaction paths were done where atoms beyond 6Å from the active exchange site were fixed.

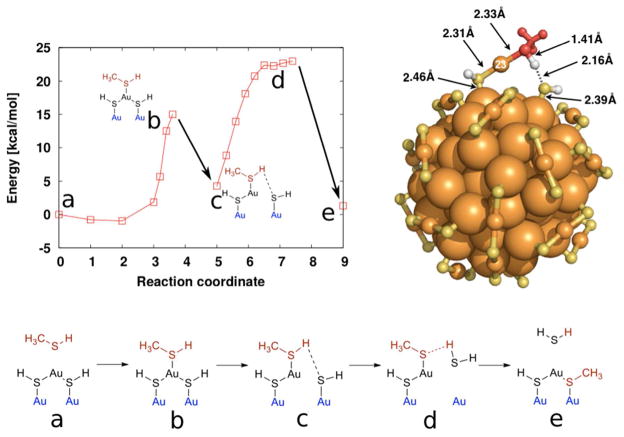

Figure 3.

Proposed ligand exchange process with methane thiol shown as energy behavior in the top-left panel and depicted as a sketch in the bottom panel. Top-right panel shows a full rendering of the hemiring-like transition state c. Configurations close to b and d have been confirmed to be at the local energy maximum by structural relaxations to the intermediate and final states, which are shown here by the arrows from b to c and from d to e respectively. Reaction coordinate is based on the distances from the sulfur of the adsorbed thiol to the Au23 atom from a to b, and from the sulfur of the desorbed thiol to the core Au-atom binding site of the staple from c to d. The structure in the top panel corresponds to reaction intermediate c.

RESULTS

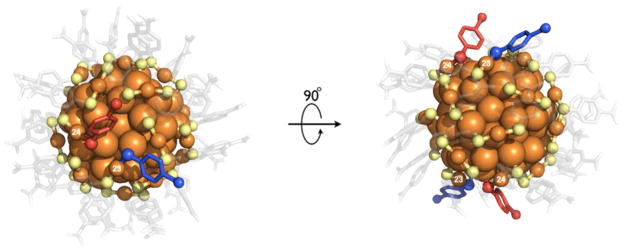

We observe ligand place-exchange occurring in two of the 22 symmetrically unique ligand sites (Figure 1). As judged by partial Br occupancy in the heterogeneous crystals at position 4 on the phenyl group of each ligand, 48.6% and 60.3% of ligands number 2 and 3 were exchanged. We name the ligands correspondingly as PMBA2 and PMBA3 as found in the crystallographic information file (CIF) in the supporting information. The same convention was used in the initial report of the Au102(p-MBA)44 crystal structure.23 The extent of place exchange at these four ligand positions accounts for ~9.1% of the total ligand population on the nanocluster, consistent with previous studies on Au38(SR)24 and Au144(SR)60 nanoclusters that find the largest rate constant for ligand exchange occurring for 8% – 25% of the total ligand population.14,15 Ligand exchange was also done with an approximate feed ratio of 2 p-BBT ligands per nanocluster. At equilibrium, exactly 1 ligand would be exchanged at this feed ratio; the experimental sum of the occupancies is determined to be 1.08 ligands per nanocluster, suggesting that the exchange reaction reached equilibrium under our experimental conditions.

Figure 1.

Down-axis and face-on views of highlighting exchanged ligands and associated relevant Au(I) atoms. The exchanged ligands are identified according to previously established convention as PMBA2 and PMBA3 and are rendered in red and blue respectively. The Au(I) atoms associated with these ligands (labeled in white numerals) are important in mechanistic interpretation and are also identified according to the previously established numbering convention. The p-MBA ligand layer is rendered semi-transparent.

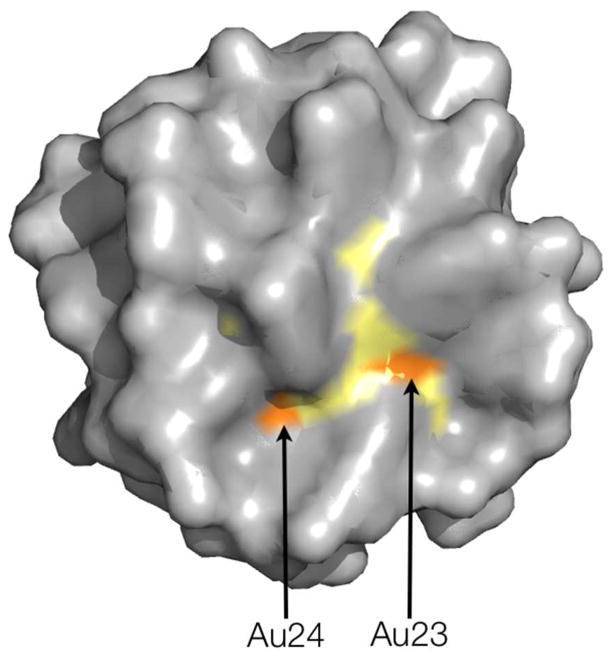

Conventionally, ligand exchange is thought to take place via an associative mechanism. Such a mechanism necessarily implies accessibility of ligand-binding gold atoms, residing in the ligand shell, to ‘nucleophilic attack’ by the incoming thiol(ate), creating an intermediate that has both incoming and outgoing ligands simultaneously bound to the accessible gold atom, suggesting in our system a transient (*) [Au102(SR)44SR’]* or [Au102(SR)44HSR’]* complex. A solvent accessibility calculation32 reveals two solvent accessible gold atoms in the crystallographic asymmetric unit, Au23 and Au24 (Figure 2) that are solvent exposed for associative ligand exchange on Au102(pMBA)44. Since PMBA2 and PMBA3 are bound to Au23 and Au24 respectively, the ligand-exchanged structure supports a simple associative exchange.

Figure 2.

A solvent accessibility surface rendering of the crystal structure with carbon, oxygen, sulfur and gold rendered in grey, grey, yellow and orange respectively. The two solvent exposed gold atoms in the asymmetric unit are labeled according to convention. The orientation of the structure in this figure is identical to the orientation of the structure in the left panel of Figure 1.

To gain more insight, we used density functional theory (DFT) computations to study details of associative reaction mechanisms for the incoming ligand in both thiol and thiolate form. Each form may be relevant under our experimental (pH) conditions, additionally both forms are reported as exchange-capable.11 For computational expediency the calculations were done for a single nanocluster in a finite computational cell, without solvent (water), and with p-MBA ligands approximated as simple SH groups. We abbreviate these idealized SH ligands as L, since they represent the most generic possible thiolate ligand. In the simplified Au102L44 model we considered associative ligand exchange of ligand position L2 from the staple unit L8 – Au23 – L2 because Au23 is the most solvent exposed gold atom (Figure 2). We considered the ‘nucleophilic attack’ of this atom with either HSCH3 (methane thiol) or SCH3− (methane thiolate) as the incoming ligand. Because the minimal ligand model used here should not participate in van der Waals interactions, the PBE exchange-functional is appropriate, since it also does not account for van der Waals interactions.

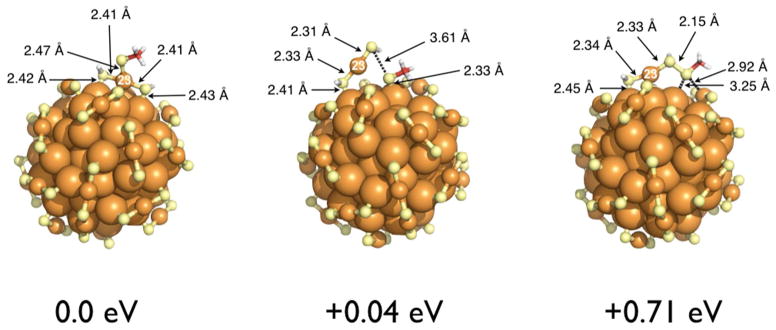

Adsorption of an incoming ligand at Au23 is the first step of associative ligand exchange, for which our calculations show a very weak adsorption minimum for methane thiol on Au23 (Figure 3a) with a much stronger adsorption minimum for the corresponding thiolate (Figure 4, left panel), at −0.05 eV (1 kcal/mol) and about −2.5 eV (59 kcal/mol) respectively. The Au23-HSCH3 and Au23-SCH3− bond distances are calculated to be approximately 3.5 Å and 2.5 Å respectively. The thiolate-Au23 bond distance is similar to the other S-Au distances in the nanocluster. Two other locally stable intermediate configurations of methane thiolate-Au23 were also found (Figure 4, middle and right panel). In one of the stable configurations (Figure 4, middle panel) the L8-Au23-L2 unit is partially desorbed from the gold core to which the excess thiolate is attached. Surprisingly, the total energy of this intermediate configuration is nearly the same as the intermediate in Figure 3 in which thiol is the incoming ligand. In the third stable methane thiolate-Au23 configuration (Figure 4, right panel) the thiolate does not bind to the core gold atom but forms a disulfide bond. This configuration is clearly endothermic with respect to the others and implies that formation of disulfide bonds is not likely in any part of the reaction.

Figure 4.

Three local minimum-energy configurations of [Au102(SH)44SCH3]−1. The energies are compared to the first configuration on the left, where the methane thiolate is strongly adsorbed on the Au23 atom. Configuration in the middle has an open protecting unit with SCH3− bound to the core separately. The rightmost structure is energetically unfavorable including sulfur-sulfur bonding.

We were able to complete a plausible reaction path for exchange using methane thiol as an incoming ligand, as summarized in Figure 3 (bottom panel). As mentioned previously, the neutral methane thiol has a low adsorption energy, about 1 kcal/mol, to the unit L8-Au23-L2. We find an activation barrier of 15.0 kcal/mol (0.65 eV) to an interesting intermediate configuration (intermediate c in Figure 3), in which the incoming methane thiol is inserted into the Au23-L2 bond of the L8-Au23-L2 staple. This intermediate is further illustrated in the top right panel of Figure 3. The geometry of this metastable intermediate, L2-H-SCH3-Au-L8 is strikingly similar to the well known “hemiring” L-Au-L-Au-L unit that is observed in all crystallographically determined thiolate protected gold nanoclusters, and is the exclusive protecting unit in all Au25(SR)18 nanocluster structures.20, 21 However, in this intermediate, one of the Au atoms in the “hemiring” is replaced by an H atom. Depending on the orientation of the residue, the observed bond lengths between the hydrogen of the incoming ligand and the sulfur of L2 vary from 1.9 Å to 2.2 Å for the longer hydrogen bond and from 1.4 Å to 1.5 Å for the shorter covalent bond. The energy of this intermediate (intermediate c in Figure 3) is slightly endothermic (4.3 kcal/mol or 0.19 eV) with respect to the initial state (Au102L44 nanocluster and an isolated methane thiolate). To complete the reaction, the L2 must be released from the structure as SH2 as described in steps from c to e in Figure 3. During desorption, the hydrogen atom of the adsorbed methane thiol is transferred to the ligand L almost immediately. The hydrogen atom selects from the two neighboring sulfurs and binds to the one that has effectively lower coordination. At the transition point (Figure 3d), a SCH3-Au-L8-Au(core) moiety is pointing out from the nanocluster to which the desorbing HSH is (still) weakly bound with a single hydrogen bond between the open-end S of the staple and H of HSH. The energy barrier for the desorption of HSH is 18.7 kcal/mol (0.81 eV). After the transition point SH2 is released from the sulfur of the open end of the active staple and the methane thiolate binds to the core gold atom forming the final configuration (Figure 3e). The total effective activation barrier for the ligand exchange process with methane thiol is 23 kcal/mol (1.0 eV). The configuration space of the second transition state is large because of the competing flexibility in energetics due to increase/decrease in the opening angle of the active staple and due to the changes in the weak hydrogen bond. Because of the flexibility, we estimate ± 0.1 eV accuracy for the activation energy at the second transition state around which we did separate calculations to sparsely map the configurations and energetics.

We determined the energetics of the net reactions for both methane thiol and methane thiolate reactions and find them both to be essentially thermoneutral (minus and plus signs of the reaction energy denote exothermic and endothermic reactions, respectively):

Control calculations for the exchange of p-MBA to p-BBT at PMBA2 and PMBA3 sites in thiol and thiolate forms yield only slightly more exothermic (−4 to −7 kcal/mol) reaction energies which were obtained by structural optimization of the initial (3a) and the final (3e) states. Although the van der Waals interactions are not included in the PBE exchange-functional, it can be assumed that the contribution to the energy of the initial and final state would be similar, as the only difference is the replacement of the COOH group with a Br atom. Consequently, in the absence of clear enthalpic contributions, the calculations suggest that this reaction is driven by entropic mixing of the chemical entities in the ligand layer. Finally, our calculated value for dissociation energy of a whole RS-Au(I)-SR unit from the nanocluster is higher than 46 kcal/mol, suggesting that a dissociative mechanism is quite energetically costly and consequently improbable.

Structural Nature of Exchange

This crystal structure was solved from a heterogeneous crystal where the ‘static substitutional disorder’ for each exchanged ligand was quantified in the crystallographic refinement process. The relative occupancies of p-BBT ligands in each exchanging site provide several insights into the structural and chemical kinetic nature of ligand exchange.

Previous studies of ligand exchange, from kinetic, NMR and EPR spectroscopic methods, generally suggested ligand exchange as an associative mechanism, and at least one previous study suggests that an RS-Au(I)-SR moiety may represent a functional unit of exchange.33

While the exchange of PMBA2 and PMBA3 is consistent with the associative exchange mechanisms, this study makes the overall picture of ligand exchange somewhat more complex. For instance, the different Br occupancy values of 48.6% and 60.3% suggest some mechanistic insights not suggested in previous studies. First, while associative mechanisms imply a dominant role for accessibility of the ‘electrophilic’ atom, solvent accessibility of the Au(I) atoms in the ligand layer does not predict absolute reactivity of the Au(I) atom toward ligand exchange. Specifically, the solvent accessibility area for Au23 and Au24 is estimated to be 1.13 Å2 and 0.19 Å2 respectively assuming a probe size of 1.4 Å, corresponding to water molecule as a solvent. However, the less exposed Au24 results in ligand exchange with greater exchanged ligand occupancy. Also, a simple associative exchange mechanism would imply that both thiolate ligands bonded to Au23 and Au24 should exchange, perhaps even at equivalent rates, meaning we should also observe substantial exchange of PMBA8 and PMBA9, bonded to Au23 and Au24 respectively.

The differences from the simple ligand exchange picture and the one observed here may be partially explained by non-covalent (i.e., π-stacking) interactions in the ligand layer and possibly selective crystallization of some ligand exchange products. The non-covalent interactions in the ligand layer are a further challenge for modeling as well, as it would require a reliable account of dispersion forces that is missing in the standard DFT computations. Possible ligand-ligand interactions should increase the activation barriers of the ligand-exchange process. Interactions with solvent molecules increase the number of possible reaction paths as well as their complexity. Selective crystallization may also mean that we do not observe exchange of ligands in the crystal structure that in fact exchanged in solution. An analysis of ligands involved in crystal contacts shows that 11 of the 22 ligands in the asymmetric unit mediate some form of crystal contact. Of the ligands attached to solvent accessible Au atoms, PMBA2, PMBA3 and PMBA9 are not involved in crystal contacts, while PMBA8 is. This analysis suggests that selective crystallization might have suppressed observation of PMBA8, but not PMBA9. In the context of these experimental complications, a full explanation of ligand exchange at solvent exposed Au(I) atoms may require a more detailed structural study of ligand exchange reactions.

Ensemble measurements of the extent of ligand exchange prior to crystallization could give insight into the extent to which selective crystallization influences our crystallographic observations. We found such measurements to be difficult, as NMR and MALDI-MS are complicated for the Au102(SR)44 system34 and elemental analysis would require grams of material, which is presently an impractical amount, to accurately quantify the small amount of Br in the exchanged product.

A further question unaddressed by this structure is how ligands that are not bonded to solvent accessible Au(I) atoms might exchange. The mechanism of exchange implied by the present X-ray crystal structure can account for exchange of 2 of the 22 symmetry unique ligands in this nanocluster. Many if not all of the 20 remaining ligands are presumed to be exchangeable, implying the existence of at least one additional mechanism of exchange.

Other structural mechanisms that are suggested as relevant for ligand exchange on MPCs include exchange of entire RS-Au(I)-SR units and translation of ligands from non-exchanging sites into exchanging sites. The ligand exchange structure suggests that RS-Au(I)-SR unit exchange cannot be the only mechanism of ligand exchange, but does not rule it out as a possible secondary mechanism of exchange for other ligands. Future work may reveal additional structural mechanisms of ligand exchange.

The differing ligand occupancies also provide some insight with regard to the kinetics of exchange. From a standpoint of chemical kinetics, previous literature suggests three exchange environments. This literature notes several deviations from ideal behavior. The dramatically different occupancies of the two symmetry unique ligands that exchange in this structure suggest an even more kinetically complicated picture in which potentially each symmetry unique ligand-exchanging site has its own exchange constant. The previously studied compounds in ligand exchange are of higher inorganic core symmetry than Au102; Au25, Au38, and Au144 conform to distorted Oh, D3, and I point groups, respectively. Both differences may result in an even more kinetically complex exchange environment on Au102(SR)44 as compared to Au25(SR)18, Au38(SR)24, and Au144(SR)60.

We notice a parallel between this work and the previous work of Stellacci and colleagues. In Stellacci’s previous work, reactivity of larger 10 and 20 nm gold nanoparticles for ligand exchange is shown to be greatest atop the highest symmetry axes (poles) of these nanoparticles.35 Similarly, we see greatest ligand reactivity for ligands atop the pseudo-5-fold symmetry axis in Au102(p-MBA)44. The ‘hairy ball theorem’36 may partially explain both results.

CONCLUSIONS

Finally, we note that just as proteins can be conceptualized as a C1 symmetric rigid alpha-carbon backbone with chemical functional groups (amino acid sidechains) in precise 3-D location/orientation, the Au102(SR)44 nanocluster can be similarly viewed as possessing a low symmetry (C2), rigid inorganic core and chemical functional groups (thiolate ligands) in precise 3-D location and orientation. We show here that these amino acid like groups can be discretely exchanged, with notable occupancy differences among those that are exchanged which may arise from kinetic differences in reactivity. Previous work suggests that most or all of these ligands are exchangeable in more aggressive exchange conditions. Since differences in the reaction kinetics of competing reactions are the foundation for all of synthetic chemistry, kinetic differences in exchange rates of the 22 symmetrically unique ligands in Au102(p-MBA)44 might enable the modification of this low symmetry macromolecule to display a very ‘protein-like’ molecular surface, with precisely positioned functional groups displaying desired charge, hydrophobicity or polarity properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by CSU Startup funds (C.J.A) and the Academy of Finland (H.H). This research was conducted while C.J.A. was a New Investigator in Alzheimer’s Disease Grant recipient from the American Federation for Aging Research. The authors acknowledge Oren Anderson and Dave Bushnell for helpful discussions of crystallography and crystallographic refinement and Jay Nix for crystallographic data collection. The DFT computations were performed at CSC – the Finnish IT Center for Science. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393) and the National Center for Research Resources (P41RR001209). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS, NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. The crystallographic information file may be found in the supporting information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Dong A, Chen J, Vora PM, Kikkawa JM, Murray CB. Nature. 2010;466:474–477. doi: 10.1038/nature09188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirkin C, Letsinger R, Mucic R, Storhoff J. Nature. 1996;382:607–609. doi: 10.1038/382607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safer D, Hainfeld JF, Wall J, Reardon J. Science. 1982;218:290–291. doi: 10.1126/science.7123234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi HS, Liu W, Liu F, Nasr K, Misra P, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Nature Nanotechnol. 2010;5:42–47. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo R, Murray R. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;127:12140–12143. doi: 10.1021/ja053119m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hicks JF, Templeton AC, Chen S, Sheran KM, Jasti R, Murray RW. Anal Chem. 1999;71:3703–3711. doi: 10.1021/ac990432w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy CJ, Lisensky GC, Leung LK, Kowach GR, Ellis AB. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8344–8348. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sardar R, Funston A, Mulvaney P, Murray R. Langmuir. 2009;25:13840–13851. doi: 10.1021/la9019475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullen C, Mulvaney P. Langmuir. 2006;22:3007–3013. doi: 10.1021/la051898e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hostetler M, Templeton A, Murray R. Langmuir. 1999;15:3782–3789. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song Y, Murray R. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7096–7102. doi: 10.1021/ja0174985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montalti M, Prodi L, Zaccheroni N, Baxter R, Teobaldi G, Zerbetto F. Langmuir. 2003;19:5172–5174. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nerambourg N, Werts MHV, Charlot M, Blanchard-Desce M. Langmuir. 2007;23:5563–5570. doi: 10.1021/la070005a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donkers RL, Song Y, Murray RW. Langmuir. 2004;20:4703–4707. doi: 10.1021/la0497494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo R, Song Y, Wang G, Murray RW. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2752–2757. doi: 10.1021/ja044638c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whetten RL, Khluryl JT, Alvarez MM, Murthyl S, Vezmarl I, Wang ZL, Stephen PW, Cleveland CL, Landman U. Adv Mater. 1996;8:428–433. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez MM, Khoury JT, Schaaff TG, Shafigullin M, Vezmar I, Whetten RL. Chem Phys Lett. 1997;266:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleveland C, Landman U, Shafigullin M, Stephens P, Whetten R. Z Phys D Atom Mol Cl. 1997;40:503–508. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleveland C, Landman U, Schaaff T, Shafigullin M, Stephens P, Whetten R. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;79:1873–1876. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu M, Aikens CM, Hollander FJ, Schatz GC, Jin R. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5883–5885. doi: 10.1021/ja801173r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heaven MW, Dass A, White PS, Holt KM, Murray RW. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3754–3755. doi: 10.1021/ja800561b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian H, Eckenhoff WT, Zhu Y, Pintauer T, Jin R. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8280–8281. doi: 10.1021/ja103592z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jadzinsky PD, Calero G, Ackerson CJ, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Science. 2007;318:430–433. doi: 10.1126/science.1148624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter M, Akola J, Lopez-Acevedo O, Jadzinsky PD, Calero G, Ackerson CJ, Whetten RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9157–9162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levi-Kalisman Y, Jadzinsky PD, Kalisman N, Tsunoyama H, Tsukuda T, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2976–2982. doi: 10.1021/ja109131w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tran N, Powell D, Dahl L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:4121–4125. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4121::aid-anie4121>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabsch W. Acta Cryst D. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldrick GM. Acta Cryst. 2008;64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mortensen JJ, Hansen LB, Jacobsen KW. Phys Rev B. 2005;71:035109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enkovaara J, Rostagaard C, Mortensen JJ, Chen J, Dułak M, Ferrighi L, Gavnholt J, Glinsvad C, Haikola V, Hansen HA, et al. J Phys Condens Matter. 2010;22:253202. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/25/253202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee B, Richards FM. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song Y, Huang T, Murray RW. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11694–11701. doi: 10.1021/ja0355731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong OA, Heinecke CL, Simone AR, Whetten RL, Ackerson CJ. Nanoscale. 2012;4:4099–4012. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30259d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeVries GA, Brunnbauer M, Hu Y, Jackson AM, Long B, Neltner BT, Uzun O, Wunsch BH, Stellacci F. Science. 2007;315:358–361. doi: 10.1126/science.1133162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rapino S, Zerbetto F. Small. 2007;3:386–388. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.