Abstract

Thrombosis can affect any venous circulation. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes deep-vein thrombosis of the leg or pelvis, and its complication, pulmonary embolism. VTE is a fairly common disease, particularly in older age, and is associated with reduced survival, substantial health-care costs, and a high rate of recurrence. VTE is a complex (multifactorial) disease, involving interactions between acquired or inherited predispositions to thrombosis and various risk factors. Major risk factors for incident VTE include hospitalization for surgery or acute illness, active cancer, neurological disease with leg paresis, nursing-home confinement, trauma or fracture, superficial vein thrombosis, and—in women—pregnancy and puerperium, oral contraception, and hormone therapy. Although independent risk factors for incident VTE and predictors of VTE recurrence have been identified, and effective primary and secondary prophylaxis is available, the occurrence of VTE seems to be fairly constant, or even increasing.

Introduction

Thrombosis can affect any branch of the venous circulation. This Review is focused on the epidemiology of venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) of the leg or pelvis, and its complication, pulmonary embolism (PE). Thrombosis affecting the superficial leg veins (such as the saphenous vein) and other venous circulations (such as those of the arms, and cerebral, mesenteric, renal, hepatic, and portal veins) is beyond the scope of this Review. VTE is a multifactorial disease, involving interactions between clinical risk factors and predispositions to thrombosis, either acquired or inherited (thrombophilias).1–5 Moreover, the type of VTE event (PE versus DVT) might also be partly heritable.6,7 In this Review, I have attempted to summarize and integrate the data relating to VTE incidence (including trends in incidence), recurrence (including predictors of recurrence), attack rates, survival (including predictors of survival), health-care costs, and risk factors.

Scope of the Review

This Review is focused on comprehensive studies of the epidemiology of objectively-diagnosed VTE, which reported the racial demography and included the full spectrum of disease occurring within a well-defined geographical area over time, separated by event type and incident versus recurrent event, as well as studies of VTE survival and recurrence that included a relevant duration of follow-up. Most epidemiological studies of VTE have addressed populations of predominantly European origin, and the data discussed in this Review primarily relate to these populations. Where they were available, data from populations originating from other continents have also been discussed. The term ‘risk factors’ relates to characteristics that have been shown by logistic regression to be associated with incident VTE, whereas ‘predictors’ relates to characteristics associated with VTE recurrence and survival via Cox proportional hazards modelling. ‘Independent’ risk factors and predictors are those characteristics that have been significantly associated with the occurrence of VTE in multivariable analyses.

Incidence of VTE

The estimated annual incidence rates of VTE among people of European ancestry range from 104 to 183 per 100,000 person-years,8–18 rates that are similar to that of stroke.19,20 Overall VTE incidence might be higher in African American populations21–23 and lower in Asian,24 Asian American,25,26 and Native American populations,27 and might vary in the African American population according to US geographical location.23 Reported incidence rates for PE (with or without DVT), and for DVT alone (without PE), range from 29 to 78, and 45 to 117, per 100,000 person-years, respectively.10,12,14–18

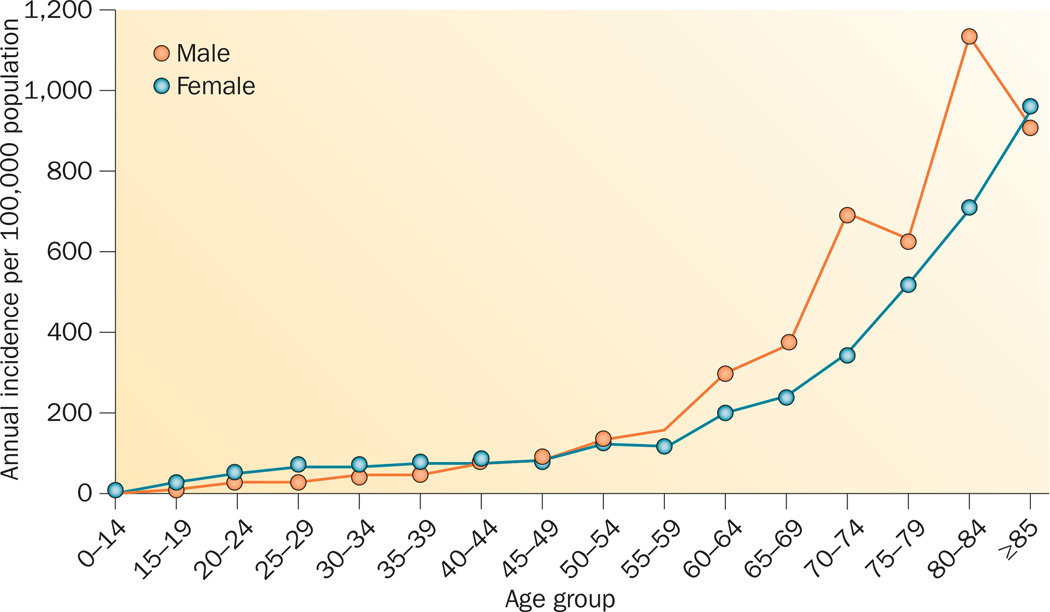

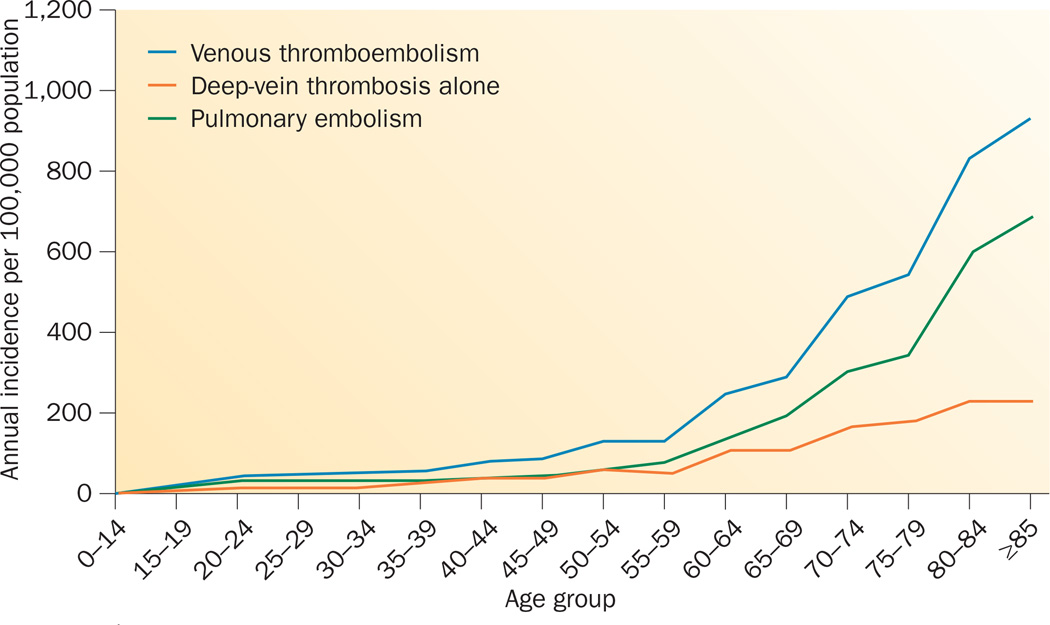

VTE is predominantly a disease of older age, and is rare prior to late adolescence.8,10–15,18 Incidence rates increase markedly with age for men and women (Figure 1) and for DVT and PE (Figure 2).10,14,15 The overall age-adjusted annual incidence rate is higher for men (130 per 100,000) than for women (110 per 100,000).10,15 Incidence rates are somewhat higher in women during childbearing years (16–44 years) compared with men of similar age, whereas incidence rates in individuals aged >45 years are generally higher in men. PE accounts for an increasing proportion of VTE with increasing age in both sexes.10 In populations of European and African origins, the percentage of incident VTE events that are idiopathic ranges from 25% to 40% (F. A. Spencer, personal communication).26,28 In one study, 19% of incident events in a study population from Asia and the Pacific Islands were found to be idiopathic.26

Figure 1.

Annual incidence of venous thromboembolism among residents of Olmsted County, MN, USA, from 1966 to 1990, by age and sex. Permission obtained from the American Medical Association © Silverstein, M. D. et al. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 585–593 (1998).

Figure 2.

Annual incidence of venous thromboembolism among residents of Olmsted County, MN, USA, from 1966 to 1990, by age. The overall incidence of venous thromboembolism is shown, along with the incidence of deep-vein thrombosis alone, and pulmonary embolism (with or without deep-vein thrombosis). Permission obtained from the American Medical Association © Silverstein, M. D. et al. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 585–593 (1998).

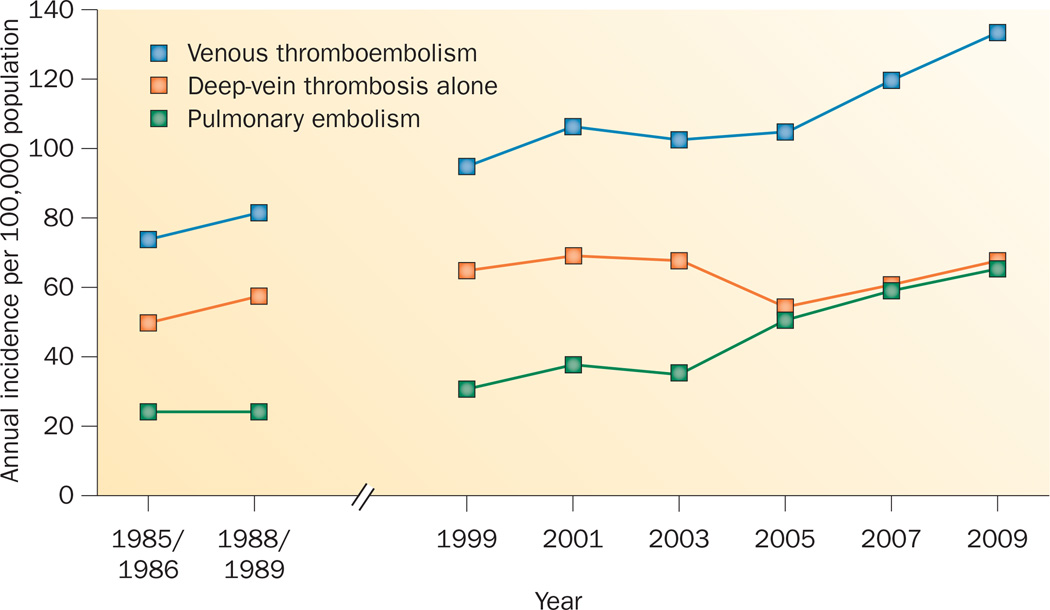

Data relating to trends in VTE incidence are limited. Incidence rates for VTE, DVT, and PE either remained constant or increased from 1981 to 2000, with a susbstantial increase in the incidence rate of VTE occurring from 2001 to 2009, mostly owing to an increasing incidence of PE (Figure 3).10,14,18,29 The rates of incident cancer-associated VTE, secondary VTE not associated with cancer, and idiopathic VTE were fairly constant from 1999 to 2009 (F. A. Spencer, personal communication). The observed increases in the rates of VTE and PE could, at least in part, reflect increased utilization of objective imaging, and improved image resolution, particularly with CT pulmonary angiography and MRI.18

Figure 3.

Trends over time in the incidence of venous thromboembolism, deep-vein thrombosis alone, and pulmonary embolism (with or without deep-vein thrombosis) among residents of Worcester, MA, USA. Permission obtained from Elsevier © Huang, W. et al. Secular trends in occurrence of acute venous thromboembolism: the Worcester VTE study (1985–2009). Am. J. Med. 127, 829–839 (2014).

Recurrence of VTE

VTE recurs frequently, and around 30% of patients with VTE experience recurrence within 10 years.16,30–40 Reported rates of recurrent VTE, DVT, and PE are 19–39, 4–13, and 15–29 per 100,000 person-years, respectively.18 In a study of residents of Olmsted County, MN, USA with incident VTE diagnosed from 1966 to 1990, the estimated cumulative incidence of first overall VTE recurrence was 1.6% at 7 days, 5.2% at 30 days, 8.3% at 90 days, 10.1% at 180 days, 12.9% at 1 year, 16.6% at 2 years, 22.8% at 5 years, and 30.4% at 10 years.31 The risk of first recurrence varies with the time since the incident event, and is highest within the first 6–12 months, with rates per 1,000 person-days of 170 at 7 days, 130 at 30 days, 30 at 90 days, 20 at 180 days and 1 year, 10 at 2 years, 6 at 5 years and 5 at 10 years.31 Although secondary prophylaxis is effective in preventing recurrence, the duration of acute treatment does not affect the rate of recurrence beyond an initial 3 months of prophylactic anticoagulation medication.33,34,41–45 These observations suggest that VTE is a chronic disease with episodic recurrence.31,32,46,47

Independent predictors of recurrence include increasing patient age,31,32,34,35,48–53 increasing BMI,31,51,53–56 male sex,31,34,50,56–64 active cancer,12,30,31,48,65–70 and neurological disease with leg paresis.31 Additional predictors of recurrence include idiopathic VTE,30,35,43,58,66,67,71–73 persistent lupus anticoagulant or antiphospholipid antibody,42,74–76 deficiency of antithrombin, protein C, or protein S,77–79 hyperhomocysteinaemia,80 persistently elevated plasma d-dimer in patients with idiopathic VTE,81–84 and, possibly, residual vein thrombosis.85,86 The risk of recurrence is modestly increased in heterozygous carriers of the factor V Leiden (F5 rs6025) or prothrombin 20210G>A (F2 rs1799963) mutations, and in patients with blood types other than O.87,88 Patients with homozygous factor V Leiden mutations or heterozygous factor V Leiden mutations combined with deficiencies of antithrombin, protein S, or protein C have an increased risk of recurrence. In patients with active cancer, factors associated with increased risk of VTE recurrence are cancer site (pancreatic, brain, lung, and ovarian cancer, myeloproliferative or myelodysplastic disorders), stage IV cancer, cancer stage progression, and leg paresis.70

Several risk factors, when present at the time of the incident VTE event, are associated with either a reduced risk of recurrence, or are not predictive of recurrence.30–32,44,58,89 In women, pregnancy or puerperium,31,38 oral contraception,31 hormone therapy,62,90 and gynaecological surgery31 at the incident VTE are associated with reduced risk of recurrence. HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibitor (statin) treatment following hospital discharge after PE reduces the risk of recurrent PE.91 Recent surgery and trauma or fracture have been reported to have no predictive value,31 or to predict a reduced risk of recurrence.30,92 Additional baseline characteristics that are not predictive of VTE recurrence include recent immobilization, tamoxifen therapy, and failed prophylaxis (incident VTE despite prophylaxis).31 For these patients, who do not have an increased risk of recurrence, and for patients with isolated calf-vein thrombosis, a shorter duration of acute therapy (heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist, or a target-specific oral anticoagulant) is probably adequate.44,66 Data relating to the use of the type of incident event as a predictor of recurrence are conflicting.31,35,36,44,49,56,93–97 However, a significant association has been found between the type of incident event and the type of recurrent event.49 Patients with sub-segmental PE have a similar 3-month recurrence risk to patients with more proximal PE.98

Several VTE recurrence prediction algorithms have been derived for the stratification of recurrence risk in patients with incident idiopathic or cancer-associated VTE. In the development of the ‘Men continue and HERDOO2’ rule, no predictors of a reduced risk of recurrence were identified in men with incident idiopathic VTE. By contrast, women with incident idiopathic VTE who had ≤1 of a set of risk factors had a significantly lower risk of VTE recurrence than those with >1.99 The risk factors were older age (≥65 years), obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), increased d-dimer level prior to stopping warfarin therapy, and signs of post-thrombotic syndrome.99 In the Vienna prediction model,100 male sex, incident VTE type (PE and/or proximal DVT versus isolated calf DVT), and increasing d-dimer levels are predictors of recurrence after idiopathic incident VTE. In the DASH prediction model,101 persistently increased d-dimer level after termination of anticoagulation therapy, age <50 years, male sex, and—in women—VTE unrelated to hormonal therapy predicted an increased risk of recurrence after an idiopathic incident VTE. The only inconsistent risk factor in these models is patient age, given that older age is associated with a higher recurrence risk among women in the HERDOO2 model,99 younger age is associated with a higher risk in men and women in the DASH model,101 and age is not a predictor of recurrence in the Vienna model.100 Depending on the model, patients with a low score have recurrence rates of 1.6–4.4% per year.102,103 If these recurrence rates were considered to be acceptable, around 50% of patients with idiopathic incident VTE and a low prediction score could avoid secondary prophylaxis, and the associated risk of bleeding complications.99–101 Among patients with active cancer and VTE, female sex, cancer site (lung) and previous VTE are high-risk predictors of VTE recurrence, and cancer site (breast) and stage (stage I rather than stage II, III, or IV) are low-risk predictors in patients receiving anticoagulation therapy.69,104

VTE attack rates

Estimated VTE attack rates (including incident and recurrent VTE) range from 142 to >300 per 100,000 person-years. Estimated attack rates for DVT and PE are 91–255 and 51–75 per 100,000 person-years, respectively.18,105 VTE attack rates related to current or recent hospitalization are much higher than the rates for people residing in the community (330 versus 8 per 100,000 person-years, respectively).105

Information is scarce regarding the total number of VTE events (incident and recurrent) occurring each year, and available estimates vary widely. In an incidence-based modelling study, the estimated total number of symptomatic VTE events per year in six European Union countries was 465,000.106 Using age-specific and sex-specific incidence rates for 1991–1995, projected to 2000, ≥260,000 incident cases of VTE have been estimated to occur in the US white population annually.13 If incidence rates are similar, then around 27,000 additional incident cases will occur in the US African American population annually. In an incidence-based modelling study that included hospital-acquired and community-acquired, incident and recurrent VTE events, 600,000 nonfatal VTE events (370,000 DVT and 270,000 PE) were estimated to occur in the USA in 2005, two-thirds of which were related to current or recent hospitalization.13 Using 2007–2009 National Hospital Discharge Survey diagnosis codes, an estimated average of 548,000 hospitalizations with VTE occurred each year among US residents aged ≥18 years, of which 349,000 were DVT and 278,000 were PE.107

Costs attributable to incident VTE

In a population-based study, adjusted mean predicted costs were found to be 2.5-fold higher for patients with VTE related to current or recent hospitalization for acute illness (US$62,838) than for hospitalized control patients matched by active cancer status ($24,464; P <0.001).108 Costs were calculated from the VTE event date (or index date for controls) to 5 years post-index, and cost differences between cases and controls were greatest ($16,897) within the first 3 months.108 Similarly, the 5-year costs were predicted to be 1.5-fold higher for patients with VTE related to current or recent hospitalization for major surgery ($55,956) than for hospitalized control patients matched by the type of surgery and active cancer status ($32,718; P <0.001).109 Again, cost differences between cases and controls were greatest ($12,381) in the first 3 months after the index date. Predicted costs over 5 years were also nearly twofold higher for patients with VTE and active cancer ($49,351) than for patients with active cancer but no VTE ($26,529; P <0.001; J. A. Heit, unpublished work). VTE associated with hospitalization was the leading cause of disability-adjusted life-years in low-income and middle-income countries, and the second most common cause in high-income countries.110

Predictors of survival after incident VTE

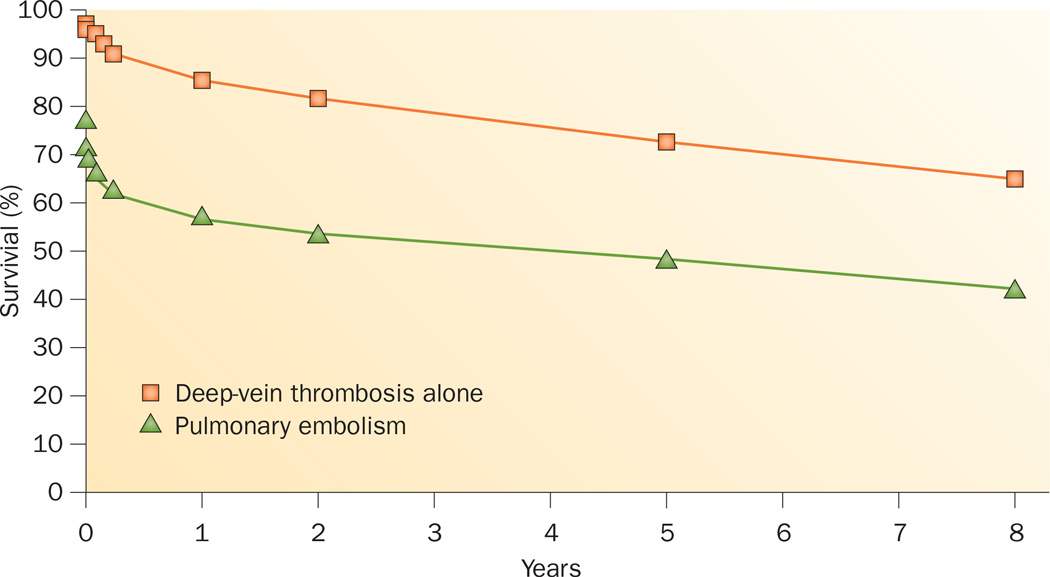

Overall, survival after VTE is worse than the expected survival in a population of similar age, sex, and ethnic distribution, and survival after PE is much worse than after DVT alone (Figure 4).36,111–115 The risk of early death in patients experiencing PE is 18-fold higher than in patients with DVT but not PE.111 PE is an independent predictor of reduced survival (compared with patients with incident DVT alone) for up to 3 months after the event, although beyond 3 months, survival after PE is similar to expected survival.15,111,112 For almost one-quarter of patients experiencing PE, the initial clinical presentation is sudden death.103 Independent predictors of reduced early survival after VTE include older age, male sex, lower BMI, confinement to a hospital or nursing home at the onset of VTE, congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, serious neurological disease, and active cancer.40,111,112,116 Additional clinical predictors of poor early survival after PE include syncope and arterial hypotension.116,117 Evidence of right heart failure, on the basis of clinical examination, plasma markers (such as cardiac troponin T and B-type natriuretic peptide), or echocardiography, predicts poor survival among normotensive patients with PE.116 Survival over time might be improving for those patients with PE who are living sufficiently long to be diagnosed and treated.111,113,118,119 Mortality is similar in patients with subsegmental PE and those with more proximal PE.98

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival among residents of Olmsted County, MN, USA with incident venous thromboembolism diagnosed 1966–1990.111 Pulmonary embolism includes cases with or without deep-vein thrombosis, where pulmonary embolism was the cause of death.

Risk factors for incident VTE

Investigators in a case–control study identified 726 women with incident VTE between 1988 and 2000 in Olmsted County, MN, USA.120 In this group, independent risk factors for incident VTE were major surgery (OR 18.95), active cancer with or without concurrent chemotherapy (OR 14.64), neurological disease with leg paresis (OR 6.10), hospitalization for acute illness (OR 5.07), nursing-home confinement (OR 4.63), trauma or fracture (OR 4.56), pregnancy or puerperium (OR 4.24), oral contraception (OR 4.03), noncontraceptive oestrogen plus progestin (OR 2.53), oestrogen (OR 1.81), progestin (OR 1.20), and BMI (OR 1.08). Among previously identified VTE risk factors, age, varicose veins, and progestin were not significantly associated with incident VTE in this multivariate analysis.120 Other risk factors for incident VTE include central vein catheterization or transvenous pacemaker placement, prior superficial vein thrombosis, urinary tract infection, increased baseline plasma fibrin d-dimer, and family history of VTE, whereas patients with chronic liver disease have a reduced risk of VTE.121–127 Compared with residents in the community, hospitalized patients have >100-fold increased incidence of VTE.128 Hospitalization and nursing-home residence together account for almost 60% of incident VTE events in the community.28,129 Notably, hospitalization for illness and hospitalization for surgery account for almost equal proportions of VTE (22% and 24%, respectively).28,129 Nursing-home residence independently accounts for over one-tenth of all VTE disease in the community.28,129

The risk of VTE in patients undergoing surgery can be stratified on the basis of patient age, type of surgery, smoking status, and the presence or absence of active cancer.130–132 The incidence of postoperative VTE is increased in patients who are aged ≥65 years.133 Surgical procedures associated with a high risk of VTE include neurosurgery, major orthopaedic surgery of the leg, renal transplantation, cardiovascular surgery, and thoracic, abdominal, or pelvic surgery for cancer.124,133,134 Obesity,135–138 and poor physical status according to American Society of Anesthesiology criteria,139 are risk factors for VTE after total hip arthroplasty.

The risk of VTE in patients hospitalized for acute illness can be stratified on the basis of age, obesity, previous VTE, thrombophilia, cancer, recent trauma or surgery, tachycardia, acute myocardial infarction or stroke, leg paresis, congestive heart failure, prolonged immobilization (bed rest), acute infection or rheumatological disorder, hormone therapy, central venous catheter, admission to an intensive or coronary care unit, white blood cell count, and platelet count.140–146 Although risk-assessment models have been derived for prediction of VTE in hospitalized, nonsurgical patients, these models are highly variable in terms of the number and type of predictors, and the strengths of associations with VTE, and lack generalizability and adequate validation.147,148

Active cancer accounts for almost 20% of all incident VTE occurring in the community.28,129 The risk of VTE is higher in patients with cancers of the brain, pancreas, ovaries, colon, stomach, lungs, kidneys, or bones, compared with other locations,149,150 and in patients with metastases.150 Patients with cancer who are receiving immunosuppressive or cytotoxic chemotherapy, including l-aspariginase,151,152 thalidomide153 or lenalidomide,154 or tamoxifen,155 are at even higher risk of VTE.121,150 Routine screening for occult (undiagnosed) cancer is controversial and probably not warranted.156,157 However, if clinical features suggest a possible occult cancer (such as idiopathic VTE, especially among patients with abdominal-vein or bilateral leg-vein thrombosis,158 or in whom VTE recurs159), then the only imaging study shown to be useful is a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis.159 Among patients with cancer, the risk of chemotherapy-associated VTE is increased in patients with pancreatic or gastric cancer, platelet count ≥350 × 109/l, haemoglobin <100 g/l or use of red cell growth factors, leukocyte count ≥11 × 109/l, or BMI ≥35 kg/m2;160 biomarkers (plasma soluble P-selectin and d-dimer) add further predictive value.161

A central venous catheter or transvenous pacemaker accounts for 9% of all incident VTE occurring in the community.28 Central venous access via femoral vein catheters is associated with a higher incidence of VTE compared with subclavian vein catheterization.162 Prior superficial vein thrombosis is an independent risk factor for subsequent DVT or PE, remote from the episode of superficial thrombophlebitis.121,163 The risk of DVT associated with varicose veins is uncertain, and seems to vary with patient age.121,164,165 Long haul (>4–6 h) air travel is associated with a slightly increased risk of VTE (1 VTE event per 4,656 flights166–168), which is preventable by the use of elastic compression stockings.169 Statin therapy can result in a 20–50% reduction in the risk of VTE.170–172 Hypertriglyceridaemia doubles the risk of VTE in postmenopausal women.173 However, the risk associated with atherosclerosis, or other risk factors for atherosclerosis, remains uncertain.126,174–178 Diabetes mellitus,120 myocardial infarction,179 current or past tobacco smoking, HDL-cholesterol level, lipoprotein(a) level, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are not independent risk factors for VTE.121,180,181 The risk associated with congestive heart failure, independent of hospitalization, is low.121,130

In women, additional risk factors for VTE include oral contraception,120,130,182–184 hormone therapy,120,185,186 pregnancy and puerperium,130,183,187 and therapy with the selective oestrogen-receptor modulator, raloxifene.188 First-generation and third-generation oral contraceptives convey higher risks than second-generation oral contraceptives.184 Injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception is associated with a threefold increased risk of VTE, whereas a levonorgestrel intrauterine device imparts no risk.189 Hormone therapy is associated with a twofold to fourfold increased risk of VTE,120,185 depending on the type of oestrogen and the mode of delivery, with evidence suggesting possibly no risk with transdermal oestrogen.190 The overall incidence of pregnancy-associated VTE is around 200 events per 100,000 women-years, a fourfold relative risk compared with nonpregnant women of childbearing age.187,191 The risk of VTE during the postpartum period is around fivefold higher than the risk during pregnancy.187 Prior superficial vein thrombosis is an independent risk factor for VTE during pregnancy or puerperium.192,193 Additional risk factors for incident VTE associated with pregnancy include varicose veins, urinary tract infection, pre-existing diabetes mellitus, stillbirth, obesity, obstetric haemorrhage, preterm delivery, and delivery by Caesarean section.194

Other conditions associated with VTE include autoimmune disorders,178 Behçet’s disease, coeliac disease,195 heparin-induced thrombocytopenia,196 homocystinuria and hyperhomocysteinaemia,197,198 hyperthyroidism,199 immune thrombocytopenia,200,201 infection,123 inflammatory bowel disease,202 intravascular coagulation and fibrinolysis/disseminated intravascular coagulation (ICF/DIC), myeloproliferative neoplasms (especially polycythaemia rubra vera and essential thrombocythaemia),203,204 chronic kidney disease with severely reduced glomerular filtration rate,205 nephrotic syndrome,206 paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria,207 rheumatoid arthritis,208,209 obstructive sleep apnoea,210,211 thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger disease), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, sickle-cell disease,212 systemic lupus erythematosus, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis).213

Studies of twins and families show that VTE is highly heritable and follows a complex mode of inheritance, involving interaction with clinical risk factors.1,3,4,7 Inherited reductions in plasma levels of natural anticoagulants, such as antithrombin, protein C, or protein S, have long been recognized as uncommon, but potent, risk factors for VTE.214–217 More recent discoveries of additional reduced natural anticoagulants218–223 or anticoagulant cofactors,224 impaired downregulation of the procoagulant system (for example, activated protein C resistance, factor V Leiden [F5 rs6025]),29,225–227 increased plasma concentrations of procoagulant factors (such as factor I [fibrinogen], factor II [prothrombin; prothrombin 20210G>A [F2 rs1799963], factors VIII, IX, and XI, von Willebrand factor [ABO rs8176719]),56,215,228–245 increased basal procoagulant activity,122,246,247 impaired fibrinolysis,248 and increased basal innate immunity activity and reactivity,249,250 have added new paradigms to the list of inherited or acquired disorders predisposing to thrombosis (thrombophilias). These plasma haemostasis-related factors, or markers of coagulation activation, correlate with increased thrombotic risk and are highly heritable.2,251–255 Inherited thrombophilias interact with obesity and tobacco smoking,254,256,257 and clinical risk factors such as oral contraception,258–261 pregnancy,262,263 hormone therapy,264–266 minor trauma,267 surgery,268,269 and cancer,270 to compound the risk of incident VTE. Similarly, interactions between genetic risk factors further increase the risk of incident VTE.271

Conclusions

VTE is a fairly common disease that recurs frequently, and is associated with reduced survival and substantial health-care costs. Although independent risk factors for VTE and predictors of VTE recurrence have been identified, and effective primary and secondary prophylaxis is available, the occurrence of VTE is generally constant or even increasing. Future research should be directed towards identification of the optimal targets for VTE prophylaxis. Groups currently considered to be at high risk of VTE, such as all patients undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery, include few individuals who would experience VTE in the absence of prophylaxis. The requirement is to identify the individuals within these groups who are at high risk of incident or recurrent VTE, who would benefit most from primary or secondary prophylaxis, thereby minimizing the risk of bleeding complications incurred by treatment of those at low risk.

Key points.

-

▪

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurs as often as stroke, and recurs frequently, with around 30% of patients with VTE experiencing recurrence within 10 years

-

▪

Occurrence of VTE, especially pulmonary embolism (PE), is associated with reduction in survival, and PE is an independent predictor of reduced survival for up to 3 months

-

▪

VTE is associated with high health-care costs and increased disability-adjusted life-years

-

▪

Despite identification of VTE risk factors, development of new prophylaxis regimens, and improved uptake of VTE prophylaxis, the occurrence of VTE is increasing

Acknowledgements

The author was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under Award Number R01HL66216. Research support was also provided by the Mayo Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.Souto JC, et al. Genetic susceptibility to thrombosis and its relationship to physiological risk factors: the GAIT study. Genetic Analysis of Idiopathic Thrombophilia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:1452–1459. doi: 10.1086/316903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariëns RA, et al. Activation markers of coagulation and fibrinolysis in twins: heritability of the prethrombotic state. Lancet. 2002;359:667–671. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07813-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen TB, et al. Major genetic susceptibility for venous thromboembolism in men: a study of Danish twins. Epidemiology. 2003;14:328–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heit JA, et al. Familial segregation of venous thromboembolism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004;2:731–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7933.2004.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zöller B, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Familial risk of venous thromboembolism in first-, second- and third-degree relatives: a nationwide family study in Sweden. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;109:458–463. doi: 10.1160/TH12-10-0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zöller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. A nationwide family study of pulmonary embolism: identification of high risk families with increased risk of hospitalized and fatal pulmonary embolism. Thromb. Res. 2012;130:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zöller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Shared familial aggregation of susceptibility to different manifestations of venous thromboembolism: a nationwide family study in Sweden. Br. J. Haematol. 2012;157:146–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson FA, Jr, et al. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1991;151:933–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansson PO, Welin L, Tibblin G, Eriksson H. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the general population. ‘The Study of Men Born in 1913’. Arch. Intern. Med. 1997;157:1665–1670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverstein MD, et al. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158:585–593. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oger E. Incidence of venous thromboembolism: a community-based study in Western France. EPI-GETBP Study Group. Groupe d’Etude de la Thrombose de Bretagne Occidentale. Thromb. Haemost. 2000;83:657–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cushman M, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Am. J. Med. 2004;117:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heit JA. Venous thromboembolism: disease burden, outcomes and risk factors. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:1611–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer FA, et al. The Worcester Venous Thromboembolism study: a population-based study of the clinical epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006;21:722–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naess IA, et al. Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;5:692–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer FA, et al. Incidence rates, clinical profile, and outcomes of patients with venous thromboembolism. The Worcester VTE study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2009;28:401–409. doi: 10.1007/s11239-009-0378-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tagalakis V, Patenaude V, Kahn SR, Suissa S. Incidence of and mortality from venous thromboembolism in a real-world population: the Q-VTE Study Cohort. Am. J. Med. 2013;126:832.e13–832.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang W, Goldberg RJ, Anderson FA, Kiefe CI, Spencer FA. Secular trends in occurrence of acute venous thromboembolism: the Worcester VTE study (1985–2009) Am. J. Med. 2014;127:829.e5–839.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothwell PM, et al. Change in stroke incidence, mortality, case-fatality, severity, and risk factors in Oxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004 (Oxford Vascular Study) Lancet. 2004;363:1925–1933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koton S, et al. Stroke incidence and mortality trends in US communities, 1987 to 2011. JAMA. 2014;312:259–268. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White RH, Zhou H, Romano PS. Incidence of idiopathic deep venous thrombosis and secondary thromboembolism among ethnic groups in California. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998;128:737–740. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider D, Lilienfeld DE, Im W. The epidemiology of pulmonary embolism: racial contrasts in incidence and in-hospital case fatality. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 2006;98:1967–1972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zakai NA, et al. Racial and regional differences in venous thromboembolism in the United States in 3 cohorts. Circulation. 2014;129:1502–1509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheuk BL, Cheung GC, Cheng SW. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in a Chinese population. Br. J. Surg. 2004;91:424–428. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA, Poggi J. Risk of pulmonary embolism and/or deep venous thrombosis in Asian-Americans. Am. J. Cardiol. 2000;85:1334–1337. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White RH, Zhou H, Murin S, Harvey D. Effect of ethnicity and gender on the incidence of venous thromboembolism in a diverse population in California in 1996. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;93:298–305. doi: 10.1160/TH04-08-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hooper WC, Holman RC, Heit JA, Cobb N. Venous thromboembolism hospitalizations among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Thromb. Res. 2002;108:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heit JA, et al. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002;162:1245–1248. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heit JA, Sobell JL, Li H, Sommer SS. The incidence of venous thromboembolism among Factor V Leiden carriers: a community-based cohort study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:305–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prandoni P, et al. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;125:1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-1-199607010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heit JA, et al. Predictors of recurrence after deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based cohort study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:761–768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansson PO, Sörbo J, Eriksson H. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after deep vein thrombosis: incidence and risk factors. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:769–774. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Dongen CJ, Vink R, Hutten BA, Büller HR, Prins MH. The incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism after treatment with vitamin K antagonists in relation to time since first event: a meta-analysis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163:1285–1293. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.11.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulman S, et al. Post-thrombotic syndrome, recurrence, and death 10 years after the first episode of venous thromboembolism treated with warfarin for 6 weeks or 6 months. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:734–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prandoni P, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after discontinuing anticoagulation in patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. A prospective cohort study in 1,626 patients. Haematologica. 2007;92:199–205. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spencer FA, et al. Patient outcomes after deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: the Worcester Venous Thromboembolism Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:425–430. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nieto JA, et al. Clinical outcome of patients with major bleeding after venous thromboembolism. Findings from the RIETE Registry. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;100:789–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White RH, Chan WS, Zhou H, Ginsberg JS. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after pregnancy-associated versus unprovoked thromboembolism. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;100:246–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kyrle PA, Rosendaal FR, Eichinger S. Risk assessment for recurrent venous thrombosis. Lancet. 2010;376:2032–2039. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60962-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verso M, et al. Long-term death and recurrence in patients with acute venous thromboembolism: the MASTER registry. Thromb. Res. 2012;130:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulman S, et al. The duration of oral anticoagulant therapy after a second episode of venous thromboembolism. The Duration of Anticoagulation Trial Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:393–398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702063360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kearon C, et al. A comparison of three months of anticoagulation with extended anticoagulation for a first episode of idiopathic venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:901–907. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903253401201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agnelli G, et al. Three months versus one year of oral anticoagulant therapy for idiopathic deep venous thrombosis. Warfarin Optimal Duration Italian Trial Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:165–169. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulman S, et al. A comparison of six weeks with six months of oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of venous thromboembolism. Duration of Anticoagulation Trial Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1661–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506223322501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agnelli G, et al. Extended oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of pulmonary embolism. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003;139:19–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-1-200307010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prandoni P, et al. Residual venous thrombosis as a predictive factor of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002;137:955–960. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-12-200212170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: the Austrian Study on Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2003;115:471–474. doi: 10.1007/BF03041030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Douketis JD, Foster GA, Crowther MA, Prins MH, Ginsberg JS. Clinical risk factors and timing of recurrent venous thromboembolism during the initial 3 months of anticoagulant therapy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:3431–3436. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murin S, Romano PS, White RH. Comparison of outcomes after hospitalization for deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Thromb. Haemost. 2002;88:407–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kyrle PA, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in men and women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2558–2563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laczkovics C, et al. Risk of recurrence after a first venous thromboembolic event in young women. Haematologica. 2007;92:1201–1207. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim TM, et al. Clinical predictors of recurrent venous thromboembolism: a single institute experience in Korea. Thromb. Res. 2009;123:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eichinger S, et al. Overweight, obesity, and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:1678–1683. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romualdi E, Squizzato A, Ageno W. Abdominal obesity and the risk of recurrent deep vein thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 2007;119:687–690. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Fuster MJ, et al. Long-term prospective study of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients younger than 50 years. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 2005;34:6–12. doi: 10.1159/000088541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heit JA, et al. Genetic variation within the anticoagulant, procoagulant, fibrinolytic and innate immunity pathways as risk factors for venous thromboembolism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;9:1133–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agnelli G, Becattini C, Prandoni P. Recurrent venous thromboembolism in men and women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:2015–2018. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200411043511919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baglin T, Luddington R, Brown K, Baglin C. Incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism in relation to clinical and thrombophilic risk factors: prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362:523–526. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baglin T, Luddington R, Brown K, Baglin C. High risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in men. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004;2:2152–2155. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McRae S, Tran H, Schulman S, Ginsberg J, Kearon C. Effect of patient’s sex on risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:371–378. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lijfering WM, et al. A lower risk of recurrent venous thrombosis in women compared with men is explained by sex-specific risk factors at time of first venous thrombosis in thrombophilic families. Blood. 2009;114:2031–2036. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Le Gal G, et al. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after a first oestrogen-associated episode. Data from the REVERSE cohort study. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;104:498–503. doi: 10.1160/TH09-10-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Christiansen SC, Lijfering WM, Helmerhorst FM, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC. Sex difference in risk of recurrent venous thrombosis and the risk profile for a second event. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2159–2168. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Douketis J, et al. Risk of recurrence after venous thromboembolism in men and women: patient level meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d813. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hutten BA, et al. Incidence of recurrent thromboembolic and bleeding complications among patients with venous thromboembolism in relation to both malignancy and achieved international normalized ratio: a retrospective analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:3078–3083. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pinede L, et al. Comparison of 3 and 6 months of oral anticoagulant therapy after a first episode of proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism and comparison of 6 and 12 weeks of therapy after isolated calf deep vein thrombosis. Circulation. 2001;103:2453–2460. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.20.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prandoni P, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding complications during anticoagulant treatment in patients with cancer and venous thrombosis. Blood. 2002;100:3484–3488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Louzada ML, Majeed H, Dao V, Wells PS. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism according to malignancy characteristics in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis: a systematic review of observational and intervention studies. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 2011;22:86–91. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328341f030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Louzada ML, et al. Development of a clinical prediction rule for risk stratification of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2012;126:448–454. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.051920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chee CE, et al. Predictors of venous thromboembolism recurrence and bleeding among active cancer patients: a population-based cohort study. Blood. 2014;123:3972–3978. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-549733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iorio A, et al. Risk of recurrence after a first episode of symptomatic venous thromboembolism provoked by a transient risk factor: a systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:1710–1716. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baglin T, et al. Does the clinical presentation and extent of venous thrombosis predict likelihood and type of recurrence? A patient-level meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2436–2442. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kovacs MJ, et al. Patients with a first symptomatic unprovoked deep vein thrombosis are at higher risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism than patients with a first unprovoked pulmonary embolism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:1926–1932. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schulman S, Svenungsson E, Granqvist S. Anticardiolipin antibodies predict early recurrence of thromboembolism and death among patients with venous thromboembolism following anticoagulant therapy. Duration of Anticoagulation Study Group. Am. J. Med. 1998;104:332–338. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garcia D, Akl EA, Carr R, Kearon C. Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of recurrence after a first episode of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. Blood. 2013;122:817–824. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jayakody Arachchillage D, Greaves M. The chequered history of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Br. J. Haematol. 2014;165:609–617. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van den Belt AG, et al. Recurrence of venous thromboembolism in patients with familial thrombophilia. Arch. Intern. Med. 1997;157:2227–2232. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.19.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vossen CY, et al. Risk of a first venous thrombotic event in carriers of a familial thrombophilic defect. The European Prospective Cohort on Thrombophilia (EPCOT) J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:459–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brouwer JL, et al. High long-term absolute risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with hereditary deficiencies of protein S, protein C or antithrombin. Thromb. Haemost. 2009;101:93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.den Heijer M, et al. Homocysteine lowering by B vitamins and the secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Blood. 2007;109:139–144. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Verhovsek M, et al. Systematic review: D-dimer to predict recurrent disease after stopping anticoagulant therapy for unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;149:481–490. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-7-200810070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Douketis J, et al. Patient-level meta-analysis: effect of measurement timing, threshold, and patient age on ability of D-dimer testing to assess recurrence risk after unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010;153:523–531. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-8-201010190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cosmi B, et al. Usefulness of repeated D-dimer testing after stopping anticoagulation for a first episode of unprovoked venous thromboembolism: the PROLONG II prospective study. Blood. 2010;115:481–488. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palareti G, et al. D-dimer to guide the duration of anticoagulation in patients with venous thromboembolism: a management study. Blood. 2014;124:196–203. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-548065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tan M, Mos IC, Klok FA, Huisman MV. Residual venous thrombosis as predictive factor for recurrent venous thromboembolim in patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis: a sytematic review. Br. J. Haematol. 2011;153:168–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Le Gal G, et al. Residual vein obstruction as a predictor for recurrent thromboembolic events after a first unprovoked episode: data from the REVERSE cohort study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011;9:1126–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ho WK, Hankey GJ, Quinlan DJ, Eikelboom JW. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with common thrombophilia: a systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:729–736. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.7.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gándara E, et al. Non-OO blood type influences the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. A cohort study. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;110:1172–1179. doi: 10.1160/TH13-06-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhu T, Martinez I, Emmerich J. Venous thromboembolism: risk factors for recurrence. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:298–310. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cushman M, et al. Hormonal factors and risk of recurrent venous thrombosis: the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism trial. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:2199–2203. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Biere-Rafi S, et al. Statin treatment and the risk of recurrent pulmonary embolism. Eur. Heart J. 2013;34:1800–1806. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.White RH, Murin S, Wun T, Danielsen B. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after surgery-provoked versus unprovoked thromboembolism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:987–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Douketis JD, Crowther MA, Foster GA, Ginsberg JS. Does the location of thrombosis determine the risk of disease recurrence in patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis? Am. J. Med. 2001;110:515–519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eichinger S, et al. Symptomatic pulmonary embolism and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004;164:92–96. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jiménez D, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with unprovoked symptomatic deep vein thrombosis and asymptomatic pulmonary embolism. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;95:562–566. doi: 10.1160/TH05-10-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Boutitie F, et al. Influence of preceding length of anticoagulant treatment and initial presentation of venous thromboembolism on risk of recurrence after stopping treatment: analysis of individual participants’ data from seven trials. BMJ. 2011;342:d3036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Galanaud JP, et al. Incidence and predictors of venous thromboembolism recurrence after a first isolated distal deep vein thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;12:436–443. doi: 10.1111/jth.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.den Exter PL, et al. Risk profile and clinical outcome of symptomatic subsegmental acute pulmonary embolism. Blood. 2013;122:1144–1149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rodger MA, et al. Identifying unprovoked thromboembolism patients at low risk for recurrence who can discontinue anticoagulant therapy. CMAJ. 2008;179:417–426. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Eichinger S, Heinze G, Jandeck LM, Kyrle PA. Risk assessment of recurrence in patients with unprovoked deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: the Vienna prediction model. Circulation. 2010;121:1630–1636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.925214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tosetto A, et al. Predicting disease recurrence in patients with previous unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a proposed prediction score (DASH) J. Thromb. Haemost. 2012;10:1019–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Clinical scores to predict recurrence risk of venous thromboembolism. Thromb. Haemost. 2012;108:1061–1064. doi: 10.1160/TH12-05-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Poli D, Palareti G. Assessing recurrence risk following acute venous thromboembolism: use of algorithms. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2013;19:407–412. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328363ed7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.den Exter PL, Kooiman J, Huisman MV. Validation of the Ottawa prognostic score for the prediction of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:998–1000. doi: 10.1111/jth.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Heit JA. Estimating the incidence of symptomatic postoperative venous thromboembolism: the importance of perspective. JAMA. 2012;307:306–307. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cohen AT, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. The number of VTE events and associated morbidity and mortality. Thromb. Haemost. 2007;98:756–764. doi: 10.1160/TH07-03-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Venous thromboembolism in adult hospitalizations—United States, 2007–2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2012;61:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cohoon KP, et al. Costs of venous thromboembolism associated with hospitalization for medical illness. Am. J. Manag. Care. 2015;21:e255–e263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cohoon KP, et al. Direct medical costs attributable to venous thromboembolism among persons hospitalized for major surgery: a population-based longitudinal study. Surgery. 2015;157:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.ISTH Steering Committee for World Thrombosis Day. Thrombosis: a major contributor to the global disease burden. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014;12:1580–1590. doi: 10.1111/jth.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Heit JA, et al. Predictors of survival after deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based, cohort study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999;159:445–453. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Goldhaber SZ, Visani L, De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) Lancet. 1999;353:1386–1389. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Janata K, et al. Mortality of patients with pulmonary embolism. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2002;114:766–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Andresen MS, et al. Mortality and recurrence after treatment of VTE: long term follow-up of patients with good life-expectancy. Thromb. Res. 2011;127:540–546. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Søgaard KK, Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Horváth-Puhó E, Sørensen HT. 30-year mortality after venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study. Circulation. 2014;130:829–836. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Agnelli G, Becattini C. Acute pulmonary embolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:266–274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0907731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Konstantinides S, et al. Association between thrombolytic treatment and the prognosis of hemodynamically stable patients with major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. Circulation. 1997;96:882–888. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Horlander KT, Mannino DM, Leeper KV. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979–1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163:1711–1717. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.14.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tsai J, Grosse SD, Grant AM, Hooper WC, Atrash HK. Trends in in-hospital deaths among hospitalizations with pulmonary embolism. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:960–961. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Barsoum MK, et al. Is progestin an independent risk factor for incident venous thromboembolism? A population-based case-control study. Thromb. Res. 2010;126:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Heit JA, et al. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cushman M, et al. Fibrin fragment D-dimer and the risk of future venous thrombosis. Blood. 2003;101:1243–1248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Smeeth L, et al. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet. 2006;367:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sweetland S, et al. Duration and magnitude of the postoperative risk of venous thromboembolism in middle aged women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bezemer ID, van der Meer FJ, Eikenboom JC, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. The value of family history as a risk indicator for venous thrombosis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009;169:610–615. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Roach RE, Lijfering WM, Flinterman LE, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC. Increased risk of CVD after VT is determined by common etiologic factors. Blood. 2013;121:4948–4954. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cannegieter SC, et al. Risk of venous and arterial thrombotic events in patients diagnosed with superficial vein thrombosis: a nationwide cohort study. Blood. 2015;125:229–235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-577783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Heit JA, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients vs community residents. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2001;76:1102–1110. doi: 10.4065/76.11.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Noboa S, Mottier D, Oger E EPI-GETBO Study Group. Estimation of a potentially preventable fraction of venous thromboembolism: a community-based prospective study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:2720–2722. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Samama MM. An epidemiologic study of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in medical outpatients: the Sirius study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160:3415–3420. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Geerts WH, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133:381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sweetland S, et al. Smoking, surgery, and venous thromboembolism risk in women: United Kingdom cohort study. Circulation. 2013;127:1276–1282. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.White RH, Zhou H, Romano PS. Incidence of symptomatic venous thromboembolism after different elective or urgent surgical procedures. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;90:446–455. doi: 10.1160/TH03-03-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Edmonds MJ, Crichton TJ, Runciman WB, Pradhan M. Evidence-based risk factors for postoperative deep vein thrombosis. ANZ J. Surg. 2004;74:1082–1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Goldhaber SZ, Tapson VF DVT FREE Steering Committee. A prospective registry of 5,451 patients with ultrasound-confirmed deep vein thrombosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2004;93:259–262. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Anderson FA, Jr, Hirsh J, White K, Fitzgerald RH., Jr Hip and Knee Registry Investigators. Temporal trends in prevention of venous thromboembolism following primary total hip or knee arthroplasty 1996–2001: findings from the Hip and Knee Registry. Chest. 2003;124(Suppl. 6):349S–356S. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6_suppl.349s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.White RH, Gettner S, Newman JM, Trauner KB, Romano PS. Predictors of rehospitalization for symptomatic venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1758–1764. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Parkin L, et al. Body mass index, surgery, and risk of venous thromboembolism in middle-aged women: a cohort study. Circulation. 2012;125:1897–1904. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mantilla CB, Horlocker TT, Schroeder DR, Berry DJ, Brown DL. Risk factors for clinically relevant pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in patients undergoing primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:552–560. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200309000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zakai NA, Wright J, Cushman M. Risk factors for venous thrombosis in medical inpatients: validation of a thrombosis risk score. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004;2:2156–2161. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chopard P, Spirk D, Bounameaux H. Identifying acutely ill medical patients requiring thromboprophylaxis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:915–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Barbar S, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;8:2450–2457. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Rothberg MB, Lindenauer PK, Lahti M, Pekow PS, Selker HP. Risk factor model to predict venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. J. Hosp. Med. 2011;6:202–209. doi: 10.1002/jhm.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Spyropoulos AC, et al. Predictive and associative models to identify hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE. Chest. 2011;140:706–714. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Woller SC, et al. Derivation and validation of a simple model to identify venous thromboembolism risk in medical patients. Am. J. Med. 2011;124:947.e2–954.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zakai NA, Callas PW, Repp AB, Cushman M. Venous thrombosis risk assessment in medical inpatients: the medical inpatients and thrombosis (MITH) study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:634–641. doi: 10.1111/jth.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Samama MM, Combe S, Conard J, Horellou MH. Risk assessment models for thromboprophylaxis of medical patients. Thromb. Res. 2012;129:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Rothberg MB. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for medical patients: who needs it? JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:1585–1586. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Chew HK, Wun T, Harvey D, Zhou H, White RH. Incidence of venous thromboembolism and its effect on survival among patients with common cancers. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:458–464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Blom JW, et al. Incidence of venous thrombosis in a large cohort of 66,329 cancer patients: results of a record linkage study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:529–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kucuk O, Kwaan HC, Gunnar W, Vazquez RM. Thromboembolic complications associated with L-asparaginase therapy. Etiologic role of low antithrombin III and plasminogen levels and therapeutic correction by fresh frozen plasma. Cancer. 1985;55:702–706. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850215)55:4<702::aid-cncr2820550405>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Liebman HA, Wada JK, Patch MJ, McGehee W. Depression of functional and antigenic plasma antithrombin III (AT-III) due to therapy with L-asparaginase. Cancer. 1982;50:451–456. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820801)50:3<451::aid-cncr2820500312>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zangari M, et al. Increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis in patients with multiple myeloma receiving thalidomide and chemotherapy. Blood. 2001;98:1614–1615. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Knight R, DeLap RJ, Zeldis JB. Lenalidomide and venous thrombosis in multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:2079–2080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc053530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Meier CR, Jick H. Tamoxifen and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998;45:608–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Baron JA, Gridley G, Weiderpass E, Nyrén O, Linet M. Venous thromboembolism and cancer. Lancet. 1998;351:1077–1080. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Piccioli A, et al. Extensive screening for occult malignant disease in idiopathic venous thromboembolism: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004;2:884–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Tafur AJ, et al. The association of active cancer with venous thromboembolism location: a population-based study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011;86:25–30. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Carrier M, et al. Systematic review: the Trousseau syndrome revisited: should we screen extensively for cancer in patients with venous thromboembolism? Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;149:323–333. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Lyman GH, Francis CW. Development and validation of a predictive model for chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111:4902–4907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Ay C, et al. Prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. Blood. 2010;116:5377–5382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Merrer J, et al. Complications of femoral and subclavian venous catheterization in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:700–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.6.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Decousus H, et al. Superficial venous thrombosis and venous thromboembolism: a large, prospective epidemiologic study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010;152:218–224. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-4-201002160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Goldhaber SZ, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary embolism. The Framingham Study. Am. J. Med. 1983;74:1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Cogo A, et al. Acquired risk factors for deep-vein thrombosis in symptomatic outpatients. Arch. Intern. Med. 1994;154:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Dalen JE. Economy class syndrome: too much flying or too much sitting? Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163:2674–2676. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Kuipers S, et al. The absolute risk of venous thrombosis after air travel: a cohort study of 8,755 employees of international organisations. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Chandra D, Parisini E, Mozaffarian D. Meta-analysis: travel and risk for venous thromboembolism. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:180–190. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Watson HG, Baglin TP. Guidelines on travel-related venous thrombosis. Br. J. Haematol. 2011;152:31–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Ray JG, et al. Use of statins and the subsequent development of deep vein thrombosis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001;161:1405–1410. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.11.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Lacut K, et al. Statins but not fibrates are associated with a reduced risk of venous thromboembolism: a hospital-based case-control study. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;18:477–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Glynn RJ, et al. A randomized trial of rosuvastatin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1851–1861. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Doggen CJ, et al. Serum lipid levels and the risk of venous thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1970–1975. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143134.87051.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Prandoni P, et al. An association between atherosclerosis and venous thrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1435–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Marcucci R, et al. Increased plasma levels of lipoprotein(a) and the risk of idiopathic and recurrent venous thromboembolism. Am. J. Med. 2003;115:601–605. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Tsai AW, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism incidence: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Arch. Intern. Med. 2002;162:1182–1189. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Sørensen HT, Horvath-Puho E, Pedersen L, Baron JA, Prandoni P. Venous thromboembolism and subsequent hospitalisation due to acute arterial cardiovascular events: a 20-year cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370:1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61745-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Zöller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Venous thromboembolism does not share strong familial susceptibility with coronary heart disease: a nationwide family study in Sweden. Eur. Heart J. 2011;32:2800–2805. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Barsoum MK, et al. Are myocardial infarction and venous thromboembolism associated? Population-based case-control and cohort studies. Thromb. Res. 2014;134:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Folsom AR, Chamberlain A. Lipoprotein(a) and venous thromboembolism. Am. J. Med. 2008;121:e17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Chamberlain AM, Folsom AR, Heckbert SR, Rosamond WD, Cushman M. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and venous thromboembolism in the Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE) Blood. 2008;112:2675–2680. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Chasan-Taber L, Stampfer MJ. Epidemiology of oral contraceptives and cardiovascular disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998;128:467–477. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-6-199803150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Rosendaal FR. Risk factors for venous thrombotic disease. Thromb. Haemost. 1999;82:610–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Gomes MP, Deitcher SR. Risk of venous thromboembolic disease associated with hormonal contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy: a clinical review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004;164:1965–1976. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Grady D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease. The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000;132:689–696. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Grady D, Hulley SB, Furberg C. Venous thromboembolic events associated with hormone replacement therapy. JAMA. 1997;278:477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Heit JA, et al. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005;143:697–706. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Adomaityte J, Farooq M, Qayyum R. Effect of raloxifene therapy on venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women. A meta-analysis. Thromb. Haemost. 2008;99:338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.van Hylckama Vlieg A, Helmerhorst FM, Rosendaal FR. The risk of deep venous thrombosis associated with injectable depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate contraceptives or a levonorgestrel intrauterine device. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:2297–2300. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.211482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Smith NL, et al. Esterified estrogens and conjugated equine estrogens and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA. 2004;292:1581–1587. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.James AH. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009;29:326–331. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.184127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Danilenko-Dixon DR, et al. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism during pregnancy or post partum: a population-based, case-control study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;184:104–110. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.107919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Roach RE, et al. The risk of venous thrombosis in individuals with a history of superficial vein thrombosis and acquired venous thrombotic risk factors. Blood. 2013;122:4264–4269. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-518159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Sultan AA, et al. Risk factors for first venous thromboembolism around pregnancy: a population-based cohort study from the United Kingdom. Blood. 2013;121:3953–3961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-469551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Ludvigsson JF, Welander A, Lassila R, Ekbom A, Montgomery SM. Risk of thromboembolism in 14,000 individuals with coeliac disease. Br. J. Haematol. 2007;139:121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Shantsila E, Lip GY, Chong BH. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. A contemporary clinical approach to diagnosis and management. Chest. 2009;135:1651–1664. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Tsai AW, et al. Serum homocysteine, thermolabile variant of methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), and venous thromboembolism: Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE) Am. J. Hematol. 2003;72:192–200. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.den Heijer M, Lewington S, Clarke R. Homocysteine, MTHFR and risk of venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.van Zaane B, et al. Increasing levels of free thyroxine as a risk factor for a first venous thrombosis: a case-control study. Blood. 2010;115:4344–4349. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Severinsen MT, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with primary chronic immune thrombocytopenia: a Danish population-based cohort study. Br. J. Haematol. 2011;152:360–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Boyle S, White RH, Brunson A, Wun T. Splenectomy and the incidence of venous thromboembolism and sepsis in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2013;121:4782–4790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-467068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Grainge MJ, West J, Card TR. Venous thromboembolism during active disease and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:657–663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61963-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Dentali F, et al. JAK2V617F mutation for the early diagnosis of Ph- myeloproliferative neoplasms in patients with venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Blood. 2009;113:5617–5623. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Barbui T, et al. Thrombosis in primary myelofibrosis: incidence and risk factors. Blood. 2010;115:778–782. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Folsom AR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and venous thromboembolism: a prospective study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010;25:3296–3301. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 206.Kayali F, Najjar R, Aswad F, Matta F, Stein PD. Venous thromboembolism in patients hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome. Am. J. Med. 2008;121:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 207.Brodsky RA. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: stem cells and clonality. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2008;2008:111–115. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]