Abstract

Background

Through 2 international traveler-focused surveillance networks (GeoSentinel and TropNet), we identified and investigated a large outbreak of acute muscular sarcocystosis (AMS), a rarely reported zoonosis caused by a protozoan parasite of the genus Sarcocystis, associated with travel to Tioman Island, Malaysia, during 2011–2012.

Methods

Clinicians reporting patients with suspected AMS to GeoSentinel submitted demographic, clinical, itinerary, and exposure data. We defined a probable case as travel to Tioman Island after 1 March 2011, eosinophilia (>5%), clinical or laboratory-supported myositis, and negative trichinellosis serology. Case confirmation required histologic observation of sarcocysts or isolation of Sarcocystis species DNA from muscle biopsy.

Results

Sixty-eight patients met the case definition (62 probable and 6 confirmed). All but 2 resided in Europe; all were tourists and traveled mostly during the summer months. The most frequent symptoms reported were myalgia (100%), fatigue (91%), fever (82%), headache (59%), and arthralgia (29%); onset clustered during 2 distinct periods: “early” during the second and “late” during the sixth week after departure from the island. Blood eosinophilia and elevated serum creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels were observed beginning during the fifth week after departure. Sarcocystis nesbitti DNA was recovered from 1 muscle biopsy.

Conclusions

Clinicians evaluating travelers returning ill from Malaysia with myalgia, with or without fever, should consider AMS, noting the apparent biphasic aspect of the disease, the later onset of elevated CPK and eosinophilia, and the possibility for relapses. The exact source of infection among travelers to Tioman Island remains unclear but needs to be determined to prevent future illnesses.

Keywords: infectious disease outbreak, sarcocystosis, parasitic disease, Malaysia, travel

On 25 October 2011, GeoSentinel, the surveillance program of the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [1], was notified of a cluster of ill German patients recently returned from Tioman Island, off the eastern coast of peninsular Malaysia (Figure 1) [2, 3]. These patients had an unusual clinical presentation: All of them reported fever and significant muscle pain, had blood eosinophilia and elevated serum creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels, and tested seronegative for trichinellosis and toxoplasmosis. A muscle biopsy from one of these patients was diagnostic for acute muscular sarcocystosis (AMS), a rarely reported zoonotic infection. The GeoSentinel (available at: http://www.istm.org/geosentinel and http://www.istm.org/eurotravnet) and TropNet (available at: http://www.tropnet.net) networks contacted their members and alerted relevant public health authorities to conduct additional case finding. Within days of the network alerts, additional patients were identified, prompting further investigation [2, 4].

Figure 1.

Tioman Island, Malaysia, and locations visited by 68 case patients with acute muscular sarcocystosis, 2011–2012. Marker color represents the frequency of visitation to each village or attraction for the 61 case patients with these data available; each patient may have visited multiple locations. Other locations visited but not mapped include “south of Tekek” (n = 4), “between Ayer Batang and Salang” (n = 3), “between Ayer Batang and Genting” (n = 1), “Tekek to Juara” (n = 1), “northwest of island” (n = 3), and a snorkeling trip circumnavigating the island by boat with multiple stops (n = 1). Tioman Island is not drawn to scale relative to the mainland.

Human muscular sarcocystosis is caused by an intracellular protozoan parasite of the genus Sarcocystis (available at: http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/sarcocystosis/index.html). First described in 1843, approximately 130 species of Sarcocystis have been identified from a variety of wild and domestic mammals, birds, and reptiles [5]. These organisms have an obligatory 2-host life cycle, alternating between predator and prey (the definitive–intermediate hosts). Humans are the definitive host for Sarcocystis hominis and Sarcocystis suihominis, acquired by eating undercooked sarcocyst-containing beef or pork, respectively. Definitive host infection is limited to the intestine and may cause acute gastroenteritis, although most infections are probably asymptomatic [6]. Humans can also become the accidental dead-end intermediate host for an unknown number of other Sarcocystis species, presumably acquired by ingesting sporocyst-containing food or water contaminated with feces from infected carnivores. In the intermediate host, generations of reproduction occur in the vasculature, ultimately leading to the formation of characteristic cysts (sarcocysts) within myocytes of skeletal, cardiac, and, infrequently, smooth muscle.

Until recently, <100 cases of human muscular sarcocystosis were reported in the literature, particularly from Malaysia [7–9]. The majority of these cases were diagnosed incidentally in asymptomatic persons or in patients whose symptoms were not clearly related to their Sarcocystis infection. At most, 10 of these cases had symptomatic AMS [10–13]; an additional recent report describes an outbreak involving 89 patients with AMS acquired on Pangkor Island, off the west coast of peninsular Malaysia [14]. Effective treatment for this disease has not been determined.

The principal objectives of this investigation were to describe the clinical, laboratory, and epidemiologic characteristics of this outbreak of AMS. We also sought to identify possible sources of infection among the ill travelers, and to alert clinicians to consider AMS when evaluating ill returned travelers.

METHODS

Epidemiologic Investigation

GeoSentinel is a global provider-based, traveler-focused sentinel surveillance network established collaboratively by ISTM and the CDC [1]. The 57 GeoSentinel sites in 24 countries consist of travel and tropical medicine clinics that actively monitor travel-related morbidity. TropNet is a European travel and tropical medicine research and surveillance network [15]. Together, these networks encompass >110 travel and tropical medicine sites and >225 participating affiliated sites worldwide.

After the first patients were reported, members of these networks were notified of the outbreak through e-mail alerts and other informal channels. In addition, the networks communicated to the larger infectious diseases community through ProMED Mail postings [16–19] and published outbreak alerts [2, 4]. Relevant global public health authorities were also notified. All were encouraged to report patients suspected of having AMS to GeoSentinel. Clinicians were asked to complete 2 structured questionnaires: one for demographic and clinical data and one for travel and exposures. They were also asked to document the date of onset for a list of symptoms that were based on our experience with the first reported patients, as well as a literature review. This outbreak investigation was determined to be public health response, and thus institutional review board review was not required. All patients gave informed consent.

We report only those patients meeting an intentionally specific outbreak case definition of probable or confirmed AMS. A probable case required travel to Tioman Island after 1 March 2011, with myositis, eosinophilia >500 cells/μL, and negative trichinellosis serology. Myositis required at least 1 of the following: a complaint of muscle pain and a CPK level >200 IU/L; muscle tenderness documented on physical examination; or histologic evidence of myositis in a muscle biopsy. Case confirmation required histologic observation of intramuscular cysts compatible with sarcocysts or the isolation of Sarcocystis species DNA from a muscle biopsy.

Laboratory Analysis

Diagnostic testing was at the discretion of the clinician but could include complete blood counts and differentials, serum biochemical testing, electrocardiography, echocardiography, imaging studies, and electromyography. Some patients were tested for specific diseases such as malaria, intestinal parasites, toxocariasis, filariasis, and dengue, chikungunya, and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Serum samples were requested, and testing at the CDC Parasitic Diseases Reference Laboratory for trichinellosis, toxoplasmosis, and strongyloidiasis was performed on available samples not previously tested as part of the initial clinical evaluation. Sera were also used by the CDC for developing a serological assay for human sarcocystosis using both whole digested merozoites and recombinant surface peptides of Sarcocystis neurona.

At the discretion of the clinician, some patients underwent muscle biopsy. All biopsies were examined histologically by a pathologist at the institution where collected. When possible, tissue blocks, frozen tissue, and extracted DNA cryoprecipitate were sent to the CDC Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch for additional examination, including histopathology, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection, and DNA sequencing analysis of Sarcocystis species 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) amplicons. For histopathologic examination, 3-μm sections were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded muscle biopsy specimens and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For electron microscopy (EM), a paraffin section was embedded in Epon-Araldite epoxy resin, removed from the slide and glued to a blank EM block, sectioned and stained, and examined in an FEI Tecnai Spirit microscope. PCR amplification was performed with a primer pair designed to amplify a fragment of approximately 800 base pairs from the 18S rRNA gene of different species of Sarcocystis [20]. Amplicons were sequenced by using BigDye version 3.1 chemistry (Applied Biosystems), and sequence data were analyzed as previously described [21].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were estimated using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Epidemiologic Characteristics of Case Patients

Demographic and Travel Characteristics

From October 2011 through April 2013, 99 ill persons who returned home after travel to Tioman Island were reported to GeoSentinel as having suspected AMS. Overall, 68 (69%) patients met the case definition and were included in the analysis; 62 were probable and 6 were confirmed cases. The median age of these patients was 34 years (range, 4–72 years); 39 (57%) were female. Of the 31 who did not meet the case definition, 24 did not satisfy criteria for myositis and 5 did not have eosinophilia, trichinellosis testing, or both.

More than three-quarters of the case patients resided in either Germany (43%) or France (34%). Fourteen (21%) lived elsewhere in Europe (6 in the Netherlands, 3 in Switzerland, 2 each in Belgium and Spain, and 1 in Italy); the 2 non-Europeans resided in Canada and Singapore. Most traveled to Tioman Island during the European summer months (Figure 2); all were tourists. The median stay was 5 days (range, 3–16 days), with 49 (72%) of the travelers staying <7 days.

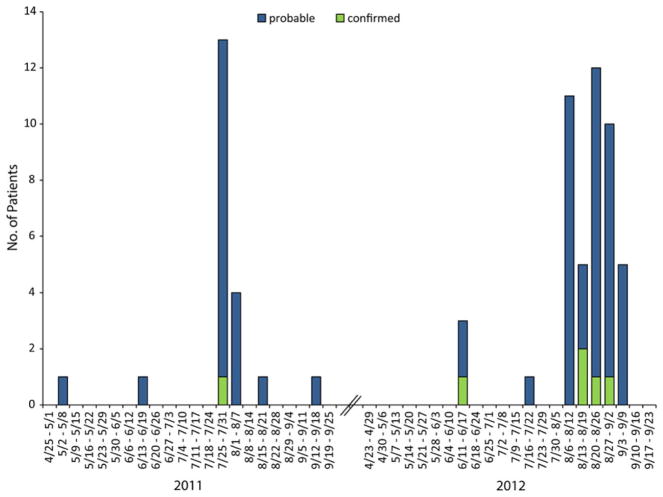

Figure 2.

Date of departure from Tioman Island, Malaysia, by week, of 68 travelers with probable and confirmed acute muscular sarcocystosis, 2011–2012. The date of departure from Tioman Island reflects the last possible point of exposure of the traveler to the Sarcocystis species parasite. The earliest departure date was 1 May 2011, and the latest was 5 September 2012.

Exposures

Complete travel and exposure data were submitted from 61 (90%) case patients. Most lodging, eating, and recreational activities were concentrated on the northwest coast of Tioman Island; no single village or attraction was visited by >40 (68%, data missing for 2) case patients (Figure 1). All travelers reported eating at restaurants and lodging at resorts, hotels, huts, or bungalows; no single eating or lodging establishment was visited by >22 (36%, Table 1). All case patients visited a beach, and all but 1 (98%) reported swimming in the ocean. All but 1 patient reported consuming drinks with ice, and most ate fresh produce that might have been washed with unsafe water and/or brushed their teeth using tap water. Cats were frequently observed in tourist areas. Reptiles (including snakes and lizards) and monkeys were infrequently contacted.

Table 1.

Exposures Reported by 61 of 68 Case Patients With Acute Muscular Sarcocystosis and With Data Available, Tioman Island, Malaysia, 2011–2012

| Travel Exposures (n = 61) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation to island | ||

| By ferry only | 42 | 69 |

| By air only | 8 | 13 |

| Both ferry and air | 11 | 18 |

| Activity exposures | ||

| Ate at restaurantsa | 61 | 100 |

| Stayed at resort, hotel, hut, or bungalowa | 61 | 100 |

| Visited a beach | 61 | 100 |

| Swam in the ocean | 60 | 98 |

| Swam in freshwater | 12 | 20 |

| Snorkeled | 53 | 87 |

| Scuba dived | 18 | 30 |

| Food/water exposuresb | ||

| Drank beverages with ice | 60 | 98 |

| Ate fresh vegetables or fruits | 47 | 77 |

| Brushed teeth with tap water | 40 | 66 |

| Animal exposures | ||

| Cats seen in restaurant kitchens, dining rooms, beachesc | 37 | 61 |

| Touched or fed a cat or kitten | 43 | 72 |

| Touched or fed a monkey | 8 | 14 |

| Touched or fed a lizard | 8 | 14 |

| Touched or fed a dog or puppy | 2 | 4 |

| Touched or fed a snake or rodent | 0 | 0 |

Missing values: Swam in fresh water (1), cats seen in restaurant kitchens, dining rooms, beaches (1), touched or fed a monkey (2), touched or fed a lizard (4), touched or fed a dog or puppy (4).

No single eating or lodging establishment was visited by >22 (36%) of travelers.

A single patient lacked any of these potential exposures.

Unsolicited information spontaneously reported in the questionnaire narrative; similar mention was not made for any other animals, including reptiles and monkeys.

Clinical and Laboratory Findings

Case patients first became ill a median of 11 days (range, 0–40 days) after departing from Tioman Island. The most frequent symptoms reported among the 68 case patients were myalgia (100%), fatigue (91%), fever (82%), headache (59%), and arthralgia (29%); other symptoms were less frequently reported (Figure 3). Patients were first evaluated by the reporting clinician at different points during the course of their illness; physical examination data were collected only on that first visit, which was a median of 44 days (range, 12–79 days) after departing from the island. Twenty-nine of 55 (53%) case patients were febrile (temperature ≥38°C); 19 of these had a temperature ≥39°C. Muscle tenderness was present among 47 of 64 (73%) and was described as moderate or severe in 32 (68%). Thirty-eight of 64 (88%) had tenderness involving their extremities; 1 reported tenderness of the masseter muscle of the face and another of the tongue. Skin rash, lung findings, and lymphadenopathy were each found in ≤3 patients. One patient reported subcutaneous nodules on the chin and neck that resolved prior to presentation, and another had muscle fasciculations involving all 4 extremities. One patient had a thrombosis of the left sigmoidal and transverse sinuses followed by pulmonary emboli; no clotting abnormality was found, and a sarcocystosis-related vasculitis could not be ruled out. One patient was pregnant at the time of infection; she experienced no complications. No patient was known to have an underlying medical condition (such as immunosuppression) that would have been expected to have affected the infection. At least 7 case patients (10%) were hospitalized; none required intensive care.

Figure 3.

Symptoms among 68 patients with acute muscular sarcocystosis, Tioman Island, Malaysia, 2011–2012. Shown are the proportions of patients experiencing each symptom at any time during the course of their illness. Symptoms reported in <5% of the case patients are not shown and include throat pain* (3%), loss of appetite (3%), and stiff neck* (1%). *Unsolicited symptom spontaneously reported in the questionnaire narrative.

Onset of the 5 most frequent symptoms appeared to cluster during 2 distinct periods: early during the second and late during the sixth week after departure (Figure 4A). No other symptom showed this pattern. To account for persons presenting at different times during the course of their illness, we also restricted the analysis to those who sought care after the fourth postdeparture week; the biphasic symptom-onset pattern persisted. For 25 (37%) patients, the illness was described as phasic, intermittent, or waxing–waning in character, with periods of symptoms separated by a period of relative improvement.

Figure 4.

Timing of specific elements of acute muscular sarcocystosis. A, Onset of the 5 most frequently reported symptoms of acute muscular sarcocystosis relative to the number of weeks since departing from Tioman Island; onset clustered during the second (early) and the sixth (late) postdeparture weeks. More than 1 onset date for at least 1 of these symptoms was reported by 15 patients (myalgia [n = 10], fever [n = 7], headache [n = 2], fatigue [n = 1]; none for arthralgia). For 25 (37%) patients, the illness was described as phasic, intermittent, or waxing–waning in character, with periods of symptoms separated by a period of relative improvement. B and C, All blood absolute eosinophil counts and serum creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) levels, respectively, for all patients relative to the number of weeks since departing Tioman Island. Each case patient may have had >1 of each laboratory determination. One absolute eosinophil count of 6200 cells/μL and 1 CPK level of 3900 U/L, each from a different patient, is not included in B and C, respectively. *Based on the case definition, >500 cells/μL is considered elevated. †Based on the case definition, >200 U/L is considered elevated.

Although few absolute eosinophil counts or serum CPK levels were performed during the first 4 postdeparture weeks, elevations in both were noted most frequently during the late period, after the fourth week postdeparture (Figure 4B and 4C). Of 10 case patients with a mildly elevated CPK-myocardial band (MB) fraction, 8 had a normal electrocardiogram (ECG), echocardiogram, or troponin, and none were thought to have cardiac pathology. One patient with a normal CPK-MB fraction, troponin, and ECG on presentation had an echocardiogram showing mild dilatation of right ventricular outflow and was thought clinically to have developed mild myocarditis. Eighteen (26%) case patients had positive Toxoplasma immunoglobulin G, but all those tested were immunoglobulin M negative (6 unknown). Strongyloides serology was positive in 4 (6%, 2 unknown). Attempts to develop and validate a serologic assay for human Sarcocystis species infection were unsuccessful due to inconsistent reactivity of sera from patients with confirmed sarcocystosis and cross-reactivity of sera from patients with known toxoplasmosis.

Patients were treated with a range of antiparasitic agents, including albendazole, as well as oral steroids. Some clinicians reported symptom improvement on oral steroids, although we could not determine whether improvement was due to the medication or the natural course of the illness. The patient with mild myocarditis was treated with oral steroids and improved, although causality could not be established.

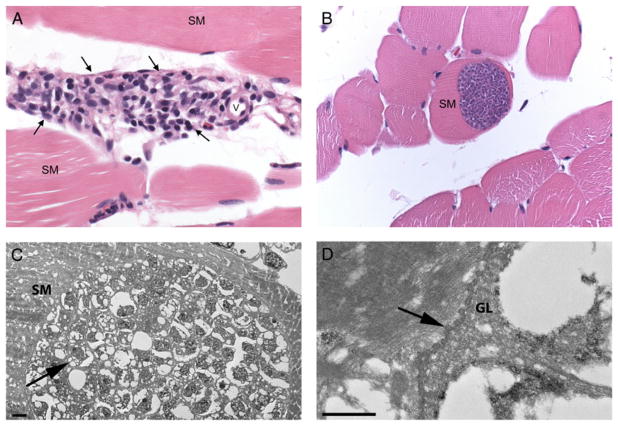

Histopathology and Species Identification

Fifteen patients had a muscle biopsy performed a median of 60 days postdeparture (range, 39–92 days). All tissue samples were examined histologically by a pathologist where collected. The CDC received tissue from a total of 14 (93%) biopsied patients, as tissue blocks, extracted DNA cryoprecipitate, frozen tissue, and/or prepared slides. Photographs of representative histopathology were received from 8 patients, 1 from the patient from whom tissue was not available. In all samples and photographs examined, histopathology showed inflammation that was predominantly perivascular within the endomysium and perimysium with a wide range of severity, from rare foci of predominantly lymphohistiocytic inflammation to more frequent foci of mixed inflammation (Figure 5A). Sarcocysts were observed histologically in the muscle of only 6 patients (40%), despite intensive searches including examination of >60 sections from a single muscle biopsy sample in which a lone sarcocyst was observed by a pathologist at the point where collected. When present, intramyocytic sarcocysts were characterized by single, large (up to 100 μm in width and several hundred micrometers in length), thin-walled, septated cysts containing innumerable, crescent-shaped bradyzoites that were approximately 4 × 8 μm (Figure 5B); no inflammation was observed immediately adjacent to any sarcocyst. By EM, large cysts were found embedded in skeletal muscle; they contained numerous, approximately 3.5 μm bradyzoites (Figure 5C). The cyst wall demonstrated short, undulating type 1 protrusions (Figure 5D) [5].

Figure 5.

Histopathology and electron microscopy. A, Skeletal muscle (SM) with inflammation (arrows) adjacent to a small vessel (v). Inflammation composed of lymphocytes and macrophages with small numbers of plasma cells, eosinophils, and rarely neutrophils. Original magnification ×400, hematoxylin and eosin staining. B, SM with intramyocytic sarcocyst. Note the absence of inflammation surrounding the sarcocyst-containing myocyte. Original magnification 400×, hematoxylin and eosin staining. C, Portion of a cyst within SM, containing abundant bradyzoites (arrow). D, Higher magnification of the cyst wall, showing short protrusions (arrow) and a fairly thin granular layer (GL). Bars = 2 μm (C) and 500 nm (D). Abbreviations: GL, granular layer; SM, skeletal muscle; v, small vessel.

Ten patients had PCR testing for Sarcocystis species DNA; 1 biopsy sample, also with sarcocysts visible on histopathology, was positive. The sequencing analysis of the amplified fragment showed 100% similarity with the 18S rRNA gene from Sarcocystis nesbitti (GenBank accession number HF544323).

DISCUSSION

We report 68 travelers with AMS acquired while vacationing on Tioman Island, Malaysia. The spectrum of AMS in humans is broad: from asymptomatic, which may characterize most infected patients [7–9], to severe and relapsing illness lasting years [11]. Comparable with other reports, the majority of the Tioman Island patients experienced muscle pain, fatigue, fever, and headache. In contrast, we did not find cough, rash, lymphadenopathy, swelling, facial tenderness, subcutaneous nodules, or cardiac abnormalities to be prominent, although patients were not examined at standardized intervals [10–14].

Onset of symptoms occurred in 2 distinct phases: early (beginning within the second week postdeparture) and late (beginning within the sixth week postdeparture). As others have reported, more than one-third of our patients experienced waxing and waning of symptoms [11, 14]. We found that the late phase corresponded with a rise in the serum CPK level and blood eosinophil count, possibly reflecting the onset of an immune-mediated myositis. All 15 muscle biopsies showed histologic evidence of varying degrees of diffuse multifocal myositis; all were done on or after the 39th day after departure from the island, and none had evidence of inflammation immediately adjacent to any observed sarcocyst. As few CPK determinations and no biopsies were done within 5 weeks of departure from the island, earlier development of myositis cannot be ruled out. The lack of clinical suspicion, reflected by the paucity of serum CPK and biopsy data in the early weeks, however, suggests that this is unlikely.

The phasic nature of AMS in humans reported here is well characterized in animals with experimentally induced intermediate-host infections [5]. Signs and symptoms of disease in animals reflect the stages of development and the migratory trajectories of the parasite as it passes from the intestine via the vascular endothelium to its final destination within the myocyte. The exact time course, however, depends on the specific species of infecting Sarcocystis and the specific host species that is infected [5]. Given the patterns observed among the Tioman Island patients, we hypothesize that disease in humans parallels that seen in animals. More work is needed to characterize the pathophysiology of disease in humans infected by Sarcocystis species as the intermediate host.

Despite the presence of swimming beaches and lodging across the island, the ill travelers concentrated most of their activities on the northwest portion; however, no obvious source of infection could be identified through epidemiologic analyses, although nearly all case patients reported potential exposure to untreated water. Cats were ubiquitous and were frequently observed in tourist areas, with nearly three-quarters of the case patients reporting having either touched or fed a cat. Although long-tailed macaques [22] and numerous reptile species, including water monitors and a variety of snakes [23], inhabit Tioman Island, few patients reported contacts. Interestingly, an environmental evaluation on the island conducted by the Malaysia Ministry of Health (MMoH) in response to this outbreak isolated Escherichia coli from almost all, and parasites from several, sampled water sources, although no Sarcocystis species were recovered [24]. In addition, no Sarcocystis species sporocysts were observed in the animal feces that were sampled, including from cats. Although the MMoH isolated Toxoplasma gondii from sampled cats, none of the case patients identified during this outbreak had evidence of acute toxoplasmosis, as might be expected if cats were the source of this outbreak. Notably, the MMoH did not sample any local rodent, bird, or reptile species during their survey of the island, and their investigation was limited in scope and conducted during the monsoon season, at a time when no infections among travelers were being reported [22–25]. Travelers to Tioman Island should be advised to practice proper precautions, including avoiding contact with animals, eating and drinking safe food and water, and washing hands frequently.

We identified S. nesbitti from the formalin-fixed muscle tissue of a patient with acute myositis and multiple sarcocysts observed on microscopic examination of histologic sections. This finding corroborates recent data showing that S. nesbitti was recovered from the muscle of 2 of 89 acutely ill patients [14]. Sarcocystis nesbitti has been considered to be a potential cause of human infections because it infects Southeast Asian species of nonhuman primates, including the long-tailed macaque, and because it resembles morphologically sarcocysts seen in humans [26–28]. Although the natural life cycle of this organism has not yet been definitively determined, evidence is mounting that S. nesbitti has a snake species as its natural definitive host [29–31]. An understanding of the natural life cycle of this zoonotic parasite would aid the development of preventive measures and messaging.

AMS among travelers is largely a clinical diagnosis that requires an understanding of symptoms and symptom progression and the geographic risk distribution of the disease. Early diagnosis is made difficult by the nonspecific nature of the early phase of the disease and the absence of a simple and accurate diagnostic test, such as serology. Diagnosis in the later phase may be easier because relatively few infectious diseases are characterized by clinical myositis and eosinophilia, the most notable exception being trichinellosis. In addition, the biphasic nature of the illness may offer a hint to the clinician. Currently, definitive diagnosis requires histologic observation of sarcocysts in or amplification of Sarcocystis species DNA by PCR from a muscle biopsy sample. However, we found that sarcocysts are likely distributed diffusely and difficult to find. Although there is currently no treatment regimen that has been shown to be effective, anti-inflammatory agents may be helpful in the management of pain. The value of specific antiparasitic agents is an area for further exploration.

These data have several limitations. At the outset of this investigation, AMS in humans was not well characterized and relevant data may have gone unrecorded. Data were gathered retrospectively and at different stages of disease, potentially affecting the accuracy of patient recall. Many clinicians from a variety of countries and practice settings participated in data collection, which may have introduced variability in data consistency. Finally, our methods likely identified more severely affected patients. Our data may not reflect disease among all patients infected with S. nesbitti, some of whom may have been asymptomatic.

Our data largely corroborate previous descriptions of human sarcocystosis and offer important new details on this emerging disease. Foremost among these is the suggestion of a 2-phase clinical presentation, commencing about 2 and 6 weeks after infection. Unfortunately, the outbreak investigation did not lend itself to determining what proportion of those infected remain asymptomatic, assessing the various therapeutic measures, or determining the typical duration of illness. Clinicians who see posttravel illness should add AMS to their differential diagnosis of the ill patient returning from Malaysia with myalgia, with or without fever, noting the apparent biphasic aspect of the disease, the later onset of elevated CPK and eosinophilia, and the possibility for relapses. Although only 1 biopsy was positive by PCR, our work and the work of others suggest S. nesbitti as a cause of human AMS. Further studies should focus on confirming the natural life cycle of this organism to develop preventive recommendations, following patients along the full course of their illnesses, and studying treatment options. To prevent future illnesses among travelers to Tioman Island, the exact source of the outbreak needs to be determined and transmission interrupted.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patients and families who gave generously and energetically of their time to contribute data to this report. We thank David O. Freedman, MD, for his many contributions early in this investigation; Alice M. Spivey, MSTCP, for her expertise and effort in creating Figures 1 and 4; Kira Harvey, MPH, for her contribution to data entry; and Emily W. Lankau, DVM, Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer, for her contribution to the design and planning and the early collection and analysis of the data.

Financial support. This work was supported by the CDC.

APPENDIX

Tioman Island Sarcocystosis Investigation Team

Members of the investigation team who contributed data and background information were Erwin Van Den Enden (deceased) and Marjan Van Esbroeck, Department of Clinical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; Wayne Ghesquiere, Vancouver General Hospital and Vancouver Island Health Authority, Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia, Canada; Duc Nguyen and Marie-Catherine Receveur, Travel Clinics and Division of Tropical Medicine–Clinical International Health, Department of Infectious and Tropical Medicine, University Hospital Center, Bordeaux, France; François Peyron, Institut de Parasitologie et de Mycologie Médicale, Hôpital de la Croix-Rousse, Lyon, France; Philippe Parola, University Hospital Institute for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Aix-Marseille University and Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Marseille, Marseille, France; Hélène Savini, Department of Tropical and Infectious Diseases, Laveran Military Teaching Hospital, Marseille, France; Eric Caumes, AP-HP, Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière, Université Pierre et Marie Curie University, Paris, France; Alice Perignon, AP-HP, Infectious and Tropical Diseases Department, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France; Michel Develoux, Service de Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales, APHP Hôpital Tenon, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France; Christophe Rapp, Service de Pathologie Infectieuse et Tropicale, Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées Bégin, Saint-Mandé, France; Christian A. Keller, Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany; Martin Haditsch, Labor Hannover, Hannover, Germany; Wolfgang Güthoff and Ines Liebold, Klinik für Gastroenterologie und Infektiologie, Klinikum Ernst von Bergmann, Potsdam, Germany; Johannes Schäfer, Tropenklinik Paul-Lechler-Krankenhaus, Tübingen, Germany; Federico Gobbi, Centre for Tropical Diseases, Hospital Sacro Cuore-Don Calabria, Negrar, Verone, Italy; Willemijn Kortmann and Gitte van Twillert, Medisch Centrum Alkmaar, Alkmaar, The Netherlands; Abraham Goorhuis, Vanessa Harris, Michèle van Vugt, and Kees Stijnis, Centre of Tropical Medicine and Travel Medicine, Department of Infectious Diseases, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Eleonora Aronica, Department of (Neuro)Pathology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Lisette van Lieshout and Meta Roestenberg, Laboratory for Parasitology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands; Jan van Wout, Bronovo Hospital, The Hague, The Netherlands; Timothy Barkham, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; Poh Lian Lim, Department of Infectious Diseases, Institute of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore; Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Singapore; Christoph Hatz, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland; Silvio D. Brugger and Hansjakob Furrer, Department of Infectious Diseases, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; François Chappuis and Yann Michel, Division of International and Humanitarian Medicine, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland; Sanya Choochumporn, Bangkok Hospital Medical Center, Thailand; Than Narkwiboonwong, Bangkok Samui Hospital, Ko Samui, Thailand; Matthew S. Dryden, Hampshire Hospitals Foundation Trust, Royal Hampshire County Hospital, Winchester, Hampshire, UK; Theresa Benedict, Sukwan Handali, and Patricia P. Wilkins, Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria, Center for Global Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Wun-Ju Shieh and Sherif Zaki, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; Laura Kogelman, Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; and Steven Hatch, Division of Infectious Disease and Immunology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester.

Footnotes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are the findings and conclusions of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han PV, et al. United States 1997–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esposito DH, Freedman DO, Neumayr A, Parola P. Ongoing outbreak of an acute muscular Sarcocystosis-like illness among travellers returning from Tioman Island, Malaysia, 2011–2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17 pii:20310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tappe D, Ernestus K, Rauthe S, et al. Initial patient cluster and first positive biopsy findings in an outbreak of acute muscular Sarcocystis-like infection in travelers returning from Tioman island, peninsular Malaysia in 2011. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:725–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03063-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: acute muscular sarcocystosis among returning travelers—Tioman Island, Malaysia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubey JP, Speer CA, Fayer R. Sarcocystosis of animals and man. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fayer R. Sarcocystis spp. in human infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:894–902. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.894-902.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaver PC, Gadgil RK, Morera P. Sarcocystis in man: a review and report of five cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:819–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pathmanathan R, Kan SP. Three cases of human Sarcocystis infection with a review of human muscular sarcocystosis in Malaysia. Trop Geogr Med. 1992;44:102–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong KT, Pathmanathan R. High prevalence of human muscle sarcocystosis in south-east Asia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:631–2. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffrey HC. Sarcosporidiosis in man. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1974;68:17–29. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(74)90247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arness MK, Brown JD, Dubey JP, Neafie RC, Granstrom DE. An outbreak of acute eosinophilic myositis attributed to human sarcocystis parasitism. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:548–53. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van den Enden E, Praet M, Joos R, Van Gompel A, Gigasse P. Eosinophilic myositis resulting from sarcocystosis. J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;98:273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehrotra R, Bisht D, Singh PA, Gupta SC, Gupta RK. Diagnosis of human sarcocystis infection from biopsies of the skeletal muscle. Pathology. 1996;28:281–2. doi: 10.1080/00313029600169164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abubakar S, Teoh BT, Sam SS, et al. Outbreak of human infection with Sarcocystis nesbitti, Malaysia, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1989–91. doi: 10.3201/eid1912.120530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouchaud O, Mühlberger N, Parola P, et al. Therapy of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Europe: MALTHER—a prospective observational multicentre study. Malar J. 2012;11:212. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman DO, Stich A, von Sonnenburg F. Sarcocystosis, human, Malaysia: Tioman Island. [Accessed 11 August 2014];ProMed. 2011 Oct 31; Available at: http://www.promedmail.org. Archive no. 20111031.3240.

- 17.Freedman DO, Caumes E. Sarcocystosis, human—Malaysia (02): Tioman Island. [Accessed 11 August 2014];ProMed. 2012 Aug 24; Available at: http://www.promedmail.org. Archive no. 20120826.1262494.

- 18.Visser LG. Sarcocystosis, human—Malaysia (03): new cases, travel related. [Accessed 11 August 2014];ProMed. 2012 Oct 21; Available at: http://www.promedmail.org. Archive no. 20121021.1356457.

- 19.Nguyen D, Receveur MC, Albert O, Malvy D. Sarcocystosis—Malaysia: (Tioman Island) travel related, 2012. [Accessed 11 August 2014];ProMed. 2013 Feb 18; Available at: http://www.promedmail.org. Archive no. 20130309.1578678.

- 20.Oryan A, Sharifiyazdi H, Khordadmehr M, Larki S. Characterization of Sarcocystis fusiformis based on sequencing and PCR-RFLP in water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) in Iran. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:563–1570. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2412-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Almeida M, Steurer F, Koru O, Herwaldt B, Pieniazek NJ, da Silva AJ. PCR amplification and sequencing of a fragment of the rRNA internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS 2) for simultaneous diagnostic characterization of 10 Leishmania spp. An alternative approach for the laboratory diagnosis of leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3143–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01177-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim BL, Lim KKP, Yong HS. The terrestrial mammals of Pulau Tioman, peninsular Malaysia, with a catalog of specimens at the Raffles Museum, National University of Singapore. Raffles Bull Zool. 1999;(suppl 6):101–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim KKP, Lim LJ. The terrestrial herpetofauna of Pulau Tioman, peninsular Malaysia. Raffles Bull Zool. 1999;(suppl 6):131–55. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husna Maizura AM, Khebir V, Chong CK, Shah A, Hakim L. Surveillance for sarcocystosis in Tioman Island, Malaysia. Malaysian J Public Health Med. 2012;12:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sodhi NS. An annotated checklist of the birds of Pulau Tioman, peninsular Malaysia. Raffles Bull Zool. 1999;(suppl 6):125–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang ZQ, Wei CG, Zen JS, et al. A taxonomic re-appraisal of Sarcocystis nesbitti (Protozoa: Sarcocystidae) from the monkey Macaca fascicularis in Yunnan, PR China. Parasitol Int. 2005;54:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kan SP, Prathap K, Dissanaike AS. Light and electron microstructure of a Sarcocystis sp. from the Malaysian long-tailed monkey, Macaca fascicularis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1979;28:634–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong KT, Pathmanathan R. Ultrastructure of the human skeletal muscle sarcocyst. J Parasitol. 1994;80:327–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian M, Chen Y, Wu L, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of Sarcocystis nesbitti (Coccidia: Sarcocystidae) suggests a snake as its probable definitive host. Vet Parasitol. 2012;183:373–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau YL, Chang PY, Tan CT, Fong MY, Mahmud R, Wong KT. Sarcocystis nesbitti infection in human skeletal muscle: possible transmission from snakes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:361–4. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau YL, Chang PY, Subramaniam V, et al. Genetic assemblage of Sarcocystis spp. in Malaysian snakes. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:257. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]