Abstract

Digital ischemia is a painful and often disfiguring event. Such an ischemic event often leads to tissue loss and can significantly affect the patient’s quality of life. Digital ischemia can be secondary to a vasculopathy, vasculitis, embolic disease, trauma, or extrinsic vascular compression. It is an especially serious complication in patients with scleroderma. Risk stratification of patients with scleroderma at risk for digital ischemia is now possible with clinical assessment and autoantibody profiles. Because there are a variety of conditions that lead to digital ischemia, it is important to understand the pathophysiology underlying each ischemic presentation in order to target therapy appropriately. Significant progress has been made in the last two decades in defining the pathophysiological processes leading to digital ischemia in rheumatic diseases. In this article we review the risk stratification, diagnosis, and management of patients with digital ischemia and provide a practical approach to therapy, particularly in scleroderma.

Keywords: digital ischemia, scleroderma, digital ulcers, Raynaud’s phenomenon

Introduction

Inadequate blood flow to living tissue is an excruciatingly painful experience and threatens the life of the tissue involved. An ischemic event to digital tissue is comparable to a pulmonary embolism or a myocardial infarction in that viability of the affected tissue is often lost and can significantly affect the patient’s quality of life. Death of digital tissue not only results in both disfigurement and functional disability, it also is the clinical manifestation of an underlying systemic disease process. Although the differential for digital ischemia is broad, in this review we focus on digital ischemia in the setting of rheumatic disease, particularly in scleroderma.

Digital ischemia is an especially serious complication in patients with scleroderma. Morbidity from digital ischemia is remarkably high in patients with this rheumatic disease; 30% of patients with persistent digital ulcers develop irreversible tissue loss (Ingraham KM, Steen VD. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2006; 54(9 Suppl.):P578) and it often requires hospitalization. As a result, when ischemia threatens the livelihood of a digit, rapid aggressive actions must be taken to prevent permanent damage. Amputation is reported to occur in one or more digits due to ischemia in 20.4% of patients with scleroderma, 9.2% of which have multiple digit loss [1].

Digital tissue vitality can be threatened by many pathological processes that compromise arterial blood supply such as thrombosis, a vasculopathy, vasculitis, embolic, and traumatic; all complicated by secondary vasospasm. Because all etiologies of digital ischemia are not alike, it is important to understand the pathophysiology underlying each ischemic presentation in order to target therapy appropriately. Significant progress has been made in the last two decades in defining the pathophysiological processes leading to digital ischemia in rheumatic diseases. This knowledge has lead to many new treatment options. Because digital ischemia is present in greater than 95% of patients with scleroderma, it will be used as our model of the disease process and to review our approach to management.

Identifying Patients at Risk

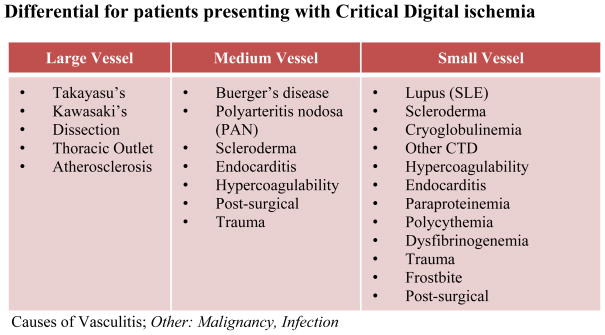

Digital ischemia results from an inadequate supply of oxygenated blood to digital tissue. The presence of digital pain associated with pallor or cyanosis of the skin of the affected digit(s) is the first clinical sign of impending digital tissue loss. When confronted with a painful discolored digit, it is imperative to quickly determine the likely etiology of the ischemia so that appropriate therapy can be promptly initiated to prevent tissue injury. An immediate assessment for predisposing risk factors for vascular disease should be conducted to elucidate the cause of the ischemic event (See Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Differential for patients presenting with Critical Digital ischemia.

Causes of Vasculitis; Other: Malignancy, Infection

Digital ulcers are representative of vascular involvement in scleroderma and occur in about 30–50% of patients with scleroderma [2] [3]. Predicting the patients who are at high risk for the development of significant vascular involvement and subsequent digital loss is important so that these high risk patients can be monitored closely to consider preventive measures and treated early when ischemia occurs. Autoantibodies and microvascular damage, as seen in nailfold capillary microscopy, are independent risk factors for predicting that the presence of Raynaud’s phenomenon is the manifestation of an underlying scleroderma disease process. Nailfold capillaries can be examined in the office using emersion oil placed on the skin and viewing the capillaries with either an ophthalmoscope or bifocal microscope. Dilated or enlarged loops with areas of capillary loss are seen in patients with scleroderma. Houtman and colleagues determined that there is an inverse relationship between the severity of Raynaud’s at first presentation and the capillary density in patients with connective tissue disease. These findings were specifically noted in patients with manifestations of the scleroderma phenotype such as sclerodactyly, digital ulcers, tuft resorption, and telangiectasias [4]. Other studies found that the association of the scleroderma specific antibodies, anti-topo I and anti-centromere antibody (ACA), with nailfold capillary microscopy increased the sensitivity in predicting that the presence of Raynaud’s is associated with a connective tissue disease [5]. Patients presenting with Raynaud’s phenomenon alone without a definite diagnosis who have a known scleroderma related autoantibody (ACA, anti-Th/To, anti-topoisomerase I, or anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies) and nailfold capillary changes are 60 times more likely to develop definite scleroderma [6] than patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon and normal capillary and negative serology. Patients with scleroderma who are positive for ACA are at an increased risk for severe digital ischemia and macrovascular events with digital loss [1, 7]. In addition, among scleroderma patients, anti-Scl70 positivity and early onset Raynaud’s is associated with an increased incidence of digital ulcers [8]. Likewise, scleroderma patients with anti-PM/Scl-75/100 antibodies are also more likely to develop digital ulcers [9].

Therefore, it is now understood that a positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), especially with positive scleroderma specific antibodies, and abnormal nailfold capillaries as detected by capillaroscopy, is predictive of secondary connective tissue disease and is not seen in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon [10–12]. ACA and anti-Th/To both predict capillary enlargement, and these antibodies and anti-RNP predict capillary loss. Interestingly, each of these antibodies was associated with a distinct rate of microvascular damage. Koenig and colleagues followed digital vascular changes defined by nailfold capillary microscopy and noted that enlarged capillaries occurred earlier in patients with anti-RNA polymerase III than in patients with anti-Th/Tho antibodies. The nailfold capillary changes occur the latest in the disease course in patients with ACA [6].

Recently, Caramaschi and colleagues studied the risk factors for ischemic digital ulcers (“DUs”) in patients with scleroderma. They found that scleroderma patients with ischemic DUs are characterized by early disease onset, delay in beginning Iloprost (a prostacyclin analog) therapy, a smoking habit, and presence of joint contractions. They proposed that a score reflecting the sum of these factors could be used to predict the risk of developing ischemic digital ulcers [13]. Alvernini and colleagues also identified major risk factors for digital ulcer development in scleroderma. They evaluated 34 Italian patients with skin ulcers and studied them prospectively over a 20-month period. They found that the most significant, independent parameters associated with the development of skin ulcers were lupus anticoagulant and the presence of avascular areas on nailfold capillaroscopy. Elevated serum IL-6 levels suggesting underlying inflammation also correlated with the above findings [14]. Both in the Caramaschi study and the study recently conducted in Germany by Sunderkotter and colleagues found that male sex, diffuse scleroderma, anti-Scl 70 positivity, inflammation, and the presence of pulmonary hypertension correlated with a high probability of presenting with digital ulcers [15]. These observations all contribute to defining the clinical phenotype of the highest risk patients.

Another means of identifying patients at risk for the development of scleroderma-related digital ulcers is through genetic studies. Combining gene expression data with clinical phenotypes more clearly defines disease subtypes. Milano and colleagues recently conducted a study using DNA microarrays and gene expression profiling with 61 skin specimens from 24 scleroderma patients. They were able to identify genes that had a high positive correlation with severe Raynaud’s and limited scleroderma patients. In addition, they identified genes in the diffuse scleroderma subgroup that correlated highly with the presence of DU’s. Interestingly, three of the patients with digital ulcers were negative for antibodies to anti-centromere antibody and anti-topoisomerase antibody suggesting the genetic profiling is an additional means of characterizing seronegative patients.

Bos and colleagues also used gene expression profiling in peripheral blood cells in an attempt to distinguish clinical subtypes in systemic sclerosis. They looked at the peripheral blood cells of twelve scleroderma patients and 6 controls and found that low expression of type I interferon response genes was associated with the presence of anti-centromere antibodies. Increased expression of type I interferon was associated with the appearance of digital ulcers and the absence of anti-centromere antibodies. As digital ulcer formation is believed to be at least partially related to imbalanced angiogenesis, and type I interferons are known to display antiangiogenic activity, the investigators speculated that there could be a role for increased type I interferon in the process of digital ulcer formation. This concept leads to another potential target in digital ulcer prevention. It is interesting, however, to note that Bos reports an inverse relationship in gene expression profiling between anticentromere antibodies and digital ulcers, as they are typically associated together in the clinical setting [16].

Another predictor of digital ulceration is the capillaroscopic skin ulcer risk index (CSURI). This tool was developed by Sebastiani and colleagues who found that the CSURI correlates with scleroderma patients who develop digital ulcers. If this tool is validated in a larger study, it could also be helpful in identifying at-risk patients, especially if used in combination with genetic profiles and clinical phenotyping [17]. In such cases, aggressive intervention and preventative measures could be taken to prevent ischemic complications.

Mechanisms of Ischemia in Scleroderma

Vasospasm

Vasospasm is seen in many of the rheumatic diseases and can manifest as benign reversible Raynaud’s phenomenon, or it can be associated with recurrent digital ischemia and tissue injury. The development of Raynaud’s phenomenon ultimately occurs as a result of interactions between nerve endings, smooth muscle cells, and the endothelium that is seen in the setting of soluble mediators (i.e., nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandins, neuropeptides etc) and is influenced by the patient’s surrounding environment, including temperature, smoking, and stress. [18].

Primary Raynaud’s disease (aka Raynaud’s phenomenon) is a vasospasm that occurs primarily as a result of sensitivity to cold temperatures or emotional stress. It occurs in 4–20% of women and 4–13% of men in the healthy population [19]. It is more common in young women, is entirely reversible, painless, and does not progress to tissue injury [20]. Several studies demonstrated a significant familial aggregation in primary Raynaud’s which suggests an inherited defect in thermoregulation [21–22]. Primary Raynaud’s is associated with distal digital color changes that progress from white to blue to red, representing the initial ischemia from the vasospasm (white), the subsequent slow circulation leading to increased amount of deoxygenated blood (blue), and the final hyperemic state after vessel dilation (red). All three stages of color change do not need to be present in order to diagnose Raynaud’s [23] (See Table 1). Although many patients with rheumatic disease have Raynaud’s phenomenon, without signs of tissue injury the presence of primary Raynaud’s is not associated with an underlying connective tissue disease [24].

Table 1.

Making the Diagnosis of Raynaud’s

| Ask the Following Questions: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Confirmed if positive response to all 3 questions | Excluded if response to 2 and 3 are negative |

Secondary Raynaud’s also occurs in response to cold temperature or emotional stress; however it occurs in the setting of underlying acquired vascular disturbance and is often associated with digital pain and ischemic ulcers. It also is occasionally associated with gangrene, which can lead to tissue loss or digital amputation. Secondary Raynaud’s is seen in 95% of scleroderma patients and is often the initial manifestation of the disease [25–26]. Secondary Raynaud’s often leads to critical ischemia in scleroderma because there is an obliterative vasculopathy of the peripheral arteries and microcirculation. It is manifest by structural disease often with a luminal narrowing greater than 75% of digital arteries due to underlying intimal fibrosis and luminal occlusion by thrombi [27–28]. Endothelial cell injury and activation lead to vascular dysfunction and vasospasm that can quickly obstruct the already marginal blood flow of the vasculopathic digital arteries.

Vasculopathy

Both the microvasculature and macrovasculature are involved in the development of digital ischemia in patients with scleroderma [29]. In scleroderma microangiopathy, a combination of intimal proliferation, medial hypertrophy, and adventitial fibrosis result in the narrowing of the vessel’s lumen and leads to progressive ischemia [30–31]. A complex interaction between activated endothelial cells, unregulated smooth muscle cells and pericytes, along with components of the extracellular matrix and intravascular circulating factors, is thought to contribute to the abnormal vascular reactivity and occlusive scleroderma vascular disease. Digital ischemia is one of the subsequent complications of this process. Macrovascular disease has been studied less than microvascular disease in scleroderma; however, it too plays a significant role in digital ischemia. Darbich and colleagues evaluated patients with scleroderma and found ulnar involvement in 56% of their 27 studied patients [32]. More recently, Hasegawa and colleagues found that macrovascular involvement was present in seven out of eight scleroderma patients with digital ulceration or gangrene who were screened by arteriography. In addition, vascular disease was not limited to the digit with ulcerations and gangrene but was also found in the surrounding non-ulcerated digits [33].

Interestingly, Caramaschi and colleagues recently noted that all of their scleroderma patients with both micro and macrovascular disease incurred digital amputation. The patients without clinical evidence of macrovascular involvement did not develop digital necrosis with need of amputation. They proposed that the combination of both micro and macrovascular involvement exceeds the compensation capacity of peripheral circulation and thus place the patients at an elevated risk of severe complications [13].

Vasculitis

The association of vasculitis and scleroderma is unusual but is reported in the literature. Of these cases, the most commonly reported vasculitis seen in scleroderma is ANCA-associated vasculitis [34]. P-ANCA seropositivity is known to predict vasculitis in patients with scleroderma [35–36]. Cases of ANCA vasculitis typically present in scleroderma as a pulmonary-renal syndrome or more commonly an ANCA associated glomerulonephritis, although reports exist with vasculitis of the nerves and skin [37–39]. ANCA is associated with digital ischemia in some patients with Wegener’s [40–42] and we witnessed digital ischemia in a patient with scleroderma and ANCA associated vasculitis.

Thrombotic phenomena

Although vein thrombosis and CNS events (e.g. stroke) are more likely, one other cause of digital gangrene in connective tissue disease is an associated hypercoaguable state due to anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS). APS is thought to not only cause a thrombotic microangiopathy, but there is also some in vitro evidence that suggests that certain anti-phospholipid antibodies (aPL) may be pro-atherogenic [43–44]. Interestingly, anti-beta2glycoprotein1 was recently reported to be independently associated with macrovascular disease in scleroderma. Boin and colleagues found that patients with digital loss in scleroderma were much more likely to be anti-beta2GPI positive and that these patients also ultimately have higher mortality rates [45]. The vascular events were associated with IgA and IgM isotypes of anti-beta2glycoprotien-1 and not the IgG isotype suggesting that these antibodies were a secondary phenomenon and not a causative factor.

Diagnosis

The approach to the patient with digital ischemia begins with a careful history which should guide the physician towards the etiology of the disease (See Figure 1). The history is followed by a thorough physical exam with particular focus on the patient’s vasculature and skin. This examination will often clarify the underlying diagnosis, the size of vessels involved, and the presence or absence of critical vascular compromise. On initial evaluation it is important to document the patient’s bilateral blood pressures and to look for any asymmetry in pressure or pulses. Asymmetrical blood pressures and asymmetrical or nonpalpable pulses can be an indication of underlying macrovascular disease as can be seen in vasculitis, atherosclerosis, embolic disease or extrinsic vascular obstruction. A positive Allen’s test in the wrists is suggestive of medium-vessel involvement and should ideally be performed in all patients with severe Raynaud’s and refractory digital ulcers on routine examination [46–47]. It is essential to listen over major arteries for bruits as this can provide insight on luminal narrowing which is noted most often in atherosclerosis, but also is seen with an underlying vasculopathy. Once these parameters are evaluated, it is necessary to look for physical signs that can direct one to the underlying diagnosis. A meticulous examination of the skin should include evaluation for sclerodactyly, telangiectases, hypopigmentation, digital pitting, loss of digital pulp, or calcinosis cutis, all of which would suggest scleroderma. Periungal capillary loop dilation is also a key finding and will place the patient in the group of patients with connective tissue diseases and can help differentiate between primary and secondary Raynaud’s. The presence of livedo reticularis or livedo rasemosa would be suggestive of antiphospholipid syndrome, while splinter hemorrhages, petechiae and/or purpura could point the examiner towards an underlying vasculitis.

Once the physical examination is complete, laboratory tests should be sent for further evaluation. However, if critical digital ischemia is present by examination, then it is an emergency and it is important not to wait until for all tests to return before initiating treatment. A listing of recommended laboratory tests is presented in Table 2, but it should be recognized that the history and examination will often dictate the priority laboratory testing needed.

Table 2.

Laboratory evaluation in digital ischemia

| Differential Diagnosis | Laboratory Testing |

|---|---|

| Scleroderma | Scl-70 antibodies, anti-centromere antibody, anti-RNP-polymerase III |

| Vasculitis (SLE, ANCA-related vasculitis, cryoglobulins, rheumatoid vasculitis, etc) | Anti-nuclear antibody screen, pANCA, cANCA, MPO, PR3, cryoglobulins, anti-dsDNA, RNP, Smith, C3, C4, ESR, CRP, RF |

| Embolic | Antiphospholipid antibodies (anti-cardiolipin antibody, Beta2 microglobulin, lupus anticoagulant) |

| Other | CMP, CBC with diff, TSH, lipid profile, urinalysis with micro |

Imaging

Doppler

Non-invasive assessment of the peripheral circulation will supplement the physical examination and may provide clues as to the cause and size of the vessels involved. Doppler ultrasound is a useful tool and a relatively cost effective way to evaluate patients with digital ischemia. The use of ultrasound is reported to differentiate between vasculopathy and vasculitis. In vasculopathy the luminal narrowing is evident, and the digital arteries can demonstrate decreased digital pulsation and are often chronically occluded. Alternatively, patients with vasculitis will often have an ultrasound image consistent with acute arterial occlusion [47–48]. Stafford and colleagues used ultrasound to evaluate macrovascular disease in scleroderma and described significant arterial narrowing with arterial walls characterized by smooth thickening along their entire length [46]. We recommend using Doppler ultrasound in the initial evaluation of all patients presenting with digital ischemia in order to quickly and accurately diagnose the size of vessels involved and to determine if surgical intervention is a viable option.

Laser Doppler imaging is a useful research tool used to evaluate microcirculatory flow [49, 50]. Because laser Doppler is able to assess more than one area of the hand at any given time it has shown to be more effective than a single probe Doppler [49]. Laser Doppler imaging can also be used to differentiate between primary Raynaud’s from patients with scleroderma [51]. Murray and colleagues suggested that combining laser Doppler with other imaging modalities such as nailfold capillaroscopy and thermal imaging is more effective than laser Doppler alone, but thermal imaging in not yet widely available [52].

Angiogram

Angiography is a well established imaging modality used to evaluate vascular disease. Digital arteriography was reported as far back as the 1960’s when several groups looked at patients whose digital vasculature was evaluated with this technique [53–55]. Takaro and colleagues noted the diagnostic utility of arteriography as they demonstrated both micro and macrovascular involvement in patients with scleroderma, and noted digital hypervascularity in patients with Raynaud’s. Dabich and colleagues later described a “characteristic pattern” of arterial involvement in the hands of patients with scleroderma. They noted, “The arch is usually of the balanced variety with broad communications between the ulnar and radial components. The radial artery is usually spared and the ulnar artery is frequently involved. The superficial arch and common digital arteries are most often uninvolved, while the proper digital arteries are obstructed in almost all patients in the mid and distal portions of the fingers.” [32].

Arteriography is now used in specific cases with digital ischemia when the underlying cause is in question or the option of surgery is considered. Park and colleagues recently studied a cohort of 19 scleroderma patients and recommended that patients with scleroderma associated with digital ulcers or severe Raynaud’s should consider angiography with ulnar revascularization if indicated because of the increased risk of digital loss with macrovascular disease [47, 56]. Angiography is also used to confirm the site of vascular occlusion prior to peripheral artery bypass grafts in the hands and feet of two patients with severe Raynaud’s [57]. The clinical application of angiography continues to grow, and based on the available data we recommend using this application to define the vascular anatomy of patients with severe digital ischemia who are candidates for angioplasty or surgery.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) is a newer, imaging modality that is used to evaluate vascular abnormalities of the hand. It is a fast, non-invasive exam that takes less than five minutes to perform and produces high quality images [58]. Allanore and colleagues used MRA to evaluate both arterial and venous lesions in patients with scleroderma. These investigators not only found substantial arterial and venous damage in the hands of these patients, but they also noted that the vascular lesions were associated with the extent of clinical disease and phenotype suggesting that MRA may be useful in evaluating disease progression [59]. MRA showed some promise in evaluating patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon when compared to conventional angiography as vasodilators are often used with conventional angiography and the true degree of vasospasm is often underestimated [58, 60]. In addition, diagnosing connective tissue disorders is also possible with MRA as these disorders in general are defined by characteristic findings on imaging such as tapering of the ulnar, radial, and proper digital arteries, superimposed vasospasm and areas of narrowing found between normal segments. The use of contrast enhanced MRA instead of standard angiography prior to vascular surgery of the hand has been proposed by some groups as it is a less invasive form of imaging [58]. The use of MRA, however, requires experienced radiologists [61]. To our knowledge, there are no large studies to date comparing MRA and conventional angiography use for imaging of the vasculature of the hand. Until such a study is conducted, conventional angiography should still be considered the gold standard for evaluating the vascular anatomy of the hand, particularly in the pre-operative setting.

Therapeutic Interventions

The approach to treating digital ischemia can be daunting given that it must be initiated quickly and effectively, and there are many new therapeutic options available. A recent study conducted in Germany by Herrgott and colleagues examined patients with digital ischemia who presented to subspecialists (rheumatologists, dermatologists, pulmonologists, and nephrologists). Their study demonstrated that cutaneous vascular complications of scleroderma are often undertreated or treated inappropriately [62]. In addition, the treatment of digital ulcers correlates with an improvement in functional status and quality of life [63]. It will be imperative in the future to standardize care for the management of the ischemic digit. We describe our approach to therapy below.

Non-medical therapy

The initial approach to treating a small ischemic digital area that presents as a mild discoloration at the tip of the finger is often is aimed at symptom control and improving tissue integrity and viability. Avoiding triggers such as cold temperatures and stress are helpful in reducing vasoconstriction. This includes adjustment of lifestyles to avoid extreme cold, shifting temperatures and proper clothing to keep the whole body warm. Studies looking at conditioning, biofeedback and relaxation techniques show variable outcomes. One large controlled trial in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon found no benefit in the use of biofeedback [64] and its use is also not recommended for secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon. The use of gloves is helpful in protecting the skin from trauma and keeping it warm in the cold. Ischemic lesions are painful and appropriate pain control is needed with acetaminophen, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and/or narcotics when needed. Smoking cessation is very important as smoking can contribute to the underlying vascular disease. In addition, topical creams and lotions can be applied to keep the affected skin moist. For more serious lesions, occlusive dressings serve to protect them from trauma and to promote healing. Hydrocolloid dressing also promote healing of digital ulcers [65].

Patients who are having a critical ischemic event should be put a rest and in a warm environment. This may mean hospitalization or stopping work for home care. Preventing trauma to the digits such as typing or repetitive hand work can improve blood flow and recovery in conjunction with other measures.

Medications

The agents used for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma vascular disease can be divided into agents that primarily work as vasodilators, those that have the potential to protect vessels form disease progression, and agents that prevent thrombosis. A given agent may have more than one effect. For example, prostaglandins can be vasodilators and protective of vessel damage. Our discussion will first outline currently used medications and then we will focus on our specific approach to critical ischemia.

Vasodilator Therapy

Alpha adrenergic blockers

Alpha adrenergic blockers were the first agents used with some success in treating Raynauds phenomenon. Alpha-2 adrenoreceptors are present throughout much of the vascular system and they play a significant role in cutaneous thermoregulation [31]. Prazosin was studied by several groups of investigators for treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon [66, 67]. A subsequent Cochrane systematic review concluded that Prazosin is modestly effective in treating Raynauds secondary to scleroderma, but that side effects can limit tolerability (Harding SE Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane.1998). In addition, several other members of this class of medications demonstrated a clinical benefit [66, 68]. Interestingly, the alpha 2c receptor, as subtype of the alpha adrenergic receptor, is specifically upregulated in cold exposure [69]. As a result, Wise and colleagues studied the efficacy and tolerability of a selective alpha 2C-adrenergic receptor blocker in scleroderma patients with vasospasm. They found that the time to rewarm a patient’s finger with secondary Raynaud’s after a cold challenge was decreased after ingestion of the drug, thus suggesting potential for therapeutic efficacy [70]. These results are promising, but these agents are not yet available and more studies are needed to validate the clinical efficacy. From a practical viewpoint, alpha adrenergic blocking agents are not the first line therapy for critical ischemia but the potential of selective new agents for the prevention of vasospasm in the digital and thermoregulatory circulation is of major interest.

Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium channel blockers are widely used for Raynaud’s and act on vascular smooth muscle to cause arterial dilation. Thompson and colleagues published a metanalysis looking at their use in Raynaud’s and reported moderate efficacy at best [71]. In addition, the magnitude of effect of calcium-channel blockers for Raynaud’s phenomenon associated with scleroderma is much smaller than in primary Raynaud’s, although a 35% improvement in attack severity and a mean reduction of about 8 attacks per 2 week period were still noted when compared to placebo. In addition, appropriate dosing is not always reached. Herrgott and colleagues showed that 92% of the German centers they surveyed did not aim for the recommended 360 mg of diltiazem or for the goal of 10 mg of amlodipine, and 80% did not aim for at least 40 mg of Nifedipine [62, 72]. Longer acting formulations can be used to minimize side effects of the medication and increase tolerability. Calcium channel blockers are also effective in the treatment of digital ulcers [73].

Nitrates

Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) has been studied in various means of administration. Initially the intravenous form was evaluated only to find that while there was an initial response, the effect was eventually blunted with disease progression [74]. GTN patches (0.2 mg/hour) were studied a few years later in patients with primary Raynaud’s and in patients with Raynauds secondary to scleroderma. The treatment was effective in both groups; however the side effects, particularly the headaches, were intolerable. Finally, Anderson and colleagues used GTN in the topical ointment formulation and found that it was effective with minimal side effects, even in patients with very thick skin [75]. While topical nitrates can improve digital blood flow, the use of these agents is limited by practical issues of difficulty with repeated application and side effects. Newer formulations are being tested and suggest some benefit in reducing Raynaud’s condition score [76]. It is our practice to use topical nitrates in conjunction with another vasodilator such as a calcium channel blocker during periods of critical ischemia of a digit.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDE-I’s)work by elevating levels of cGMP, causing intracellular calcium level to fall and leading to vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Through this mechanism PDE-I’s cause vasodilation and increase perfusion to distal tissues [77]. This class of drugs has demonstrated significant effects in patients with digital ischemia [78–81]. The five drugs available in this class of medications include sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil, pentoxifylline, and cilostazol, and the first two listed are better studied. Fries and colleagues conducted a double-blind, placebo controlled fixed dose crossover study with 16 patients to evaluate the effects of sildenafil on symptoms of capillary perfusion in patients with Raynaud’s. They found that sildenafil was associated with a decreased incidence and duration of Raynaud’s as well as a decreased Raynaud’s Condition Score. Capillary blood flow velocity increased in individual patients and the mean capillary blood flow velocity of all patients who received sildenafil more than quadrupled [78]. Although promising results are also reported anecdotally with vardenafil and tadalafil [82, 83], a recent randomized placebo controlled trial using tadalafil suggested no benefit over placebo [84]. Unfortunately, the numbers were small as only 39 patients with scleroderma were enrolled. Large randomized controlled trials are still needed to validate the use of phosphodiesterase inhibitors in secondary Raynaud’s. In our uncontrolled experience we have clinical success using a phosphodiesterase inhibitor for severe Raynaud’s secondary to scleroderma when used in conjunction with a calcium channel blocker but often see less benefit with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor alone..

Prostacyclins

Prostanoids are beneficial to both the micro and microvasculature as they induce vasodilation, increase intracellular cAMP, and prevent smooth muscle proliferation [85]. Prostacylcins in particular are found to be effective therapy for Raynaud’s and digital ischemia. Intravenous Iloprost is now a popular intervention outside the USA for the treatment of severe Raynaud’s secondary to scleroderma as it decreases the frequency and severity of attacks and prevents and heals digital ulcers [63, 86]. Cyclic Iloprost is now used for severe Raynaud’s and digital ulcers using various protocols [13, 63, 87–90]. These reports suggest that using prostacylcin by intravenous delivery intermittently can prevent digital ischemic events. Low dose (0.5 ng/kg compared to 2 ng/kg body weight per minute) Iloprost was shown to be equally effective [91]. Several authors reported that subcutaneous Treprostanil is also effective in the treatment of severe digital ulcerations [85, 92]. Of note, the efficacy of oral prostacyclins was also studied in the last decade for treatment of severe Raynaud’s and digital ulceration. However, several trials using oral Iloprost, beraprost, and cicaprost showed no significant benefit over placebo [93–95]. A trial testing a new formulation of oral Treprostinil is underway for the treatment of digital ulcers in patients with scleroderma. Inhaled preparations of Treprostinil and Iloprost are available but not studied in the treatment of Raynaud’s or digital ischemia.

Intravenous and Transdermal PGE1

Transdermal PGE1 ethyl ester was also reported to be effective in improving blood flow in capillaries in the skin in systemic scleroderma patients and in healing acral skin lesions in patients with scleroderma [96, 97]. However, this agent is not readily available. Intravenous PGE1 is used in the treatment of Raynaud’s and is an alternative to prostacyclin therapy [98].

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB’s) were also studied in scleroderma in relation to digital ischemia. Initial studies showed promise as captopril produced a significant improvement in cutaneous blood flow; however, it was not shown to alter the frequency or severity of Raynaud’s attacks [99]. A subsequent study also showed promise as enalapril demonstrated some promise in reducing the frequency of primary Raynaud’s attacks [100]. However, in further study and investigation with clinical trials, there were ultimately mixed results [101]. Most recently, Gliddon and colleagues organized a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating quinapril 80 mg/day, or the maximum tolerated dosage, in over 200 patients with limited scleroderma or with Raynaud’s phenomenon and the presence of scleroderma specific antinuclear antibodies. They treated the cohort for 2–3 years and were unable to demonstrate any benefit in limiting the occurrence of digital ulcers or influencing the frequency or severity of the Raynaud’s episodes [102]. As a result, this class of medications is not recommended for treatment of Raynaud’s or digital ulcers.

SSRI’s

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have the potential of increasing regional blood flow by blocking the uptake of the vasoconstrictor serotonin. A small study using fluoxetine demonstrated some benefit compared to low dose nifedipine in Raynaud’s although it is not studied for the treatment of digital ulcers [103]. We have used this agent in conjunction with a calcium channel blocker or when low blood pressure limits our ability to use more potent vasodilators.

Vasoprotective agents

Anti-platelet agents

Several groups reported elevated platelet activity in patients with scleroderma [104–107]. In one such study scleroderma platelet activation markers correlated with disease activity and severity [108]. In addition, through the use of combination therapy with aspirin and dipyramidole, significant reductions in circulating platelet aggregates and beta-thromboglobulin levels were achieved [104]. Although one double blind placebo-controlled trial reported no benefit with combination therapy with aspirin and dipyramidole versus placebo, it was a short trial over only a two year period in a group of only 28 patients. Therefore no meaningful conclusions can be drawn regarding long term benefits [109]. We regularly use low dose (81 mg) aspirin therapy in our scleroderma patients with significant vascular disease because it makes biological sense.

Endothelial Receptor antagonists

The endothelial receptor antagonists also show promise in preventing digital ulcers and have vasculoprotective effects. Korn and colleagues conducted a small preliminary study with 122 patients evaluating the effect on preventing digital ulcers. They found that patients receiving bosentan had a 48% reduction in the mean number of new ulcers during the treatment period, suggesting that it could be promising [110]. A second study, RAPIDS 2, found similar benefit in prevention of new ulcers, particularly in patients with a high number of digital ulcers at baseline. On the other hand, in RAPIDS 2, a trial of 24-week duration with 198 subjects, higher rates of healing of ulcers were seen with placebo than active drug. At the end of 24 weeks of drug therapy, there were no differences between active treatment and placebo in net DU burden, pain, measures of activities of daily living by HAQ or UK Functional Score (UKFS) or in hospitalization rates [111]. Larger studies will be needed to determine efficacy and long term outcomes, but these findings are encouraging.

Statins

Statins more recently became a focus of scleroderma research. Statins demonstrate vasculoprotective effects by decreasing LDL, increasing HDL, decreasing free radicals, coagulation, and blood viscosity, decreasing matrix metalloproteases, and increasing platelet function [31, 112, 113]. Abou-Raya and colleagues recently looked at 84 patients with scleroderma and matched them with 75 control subjects to evaluate the effects of statins on patients with Raynaud’s and digital ulcers. They found that the overall number of digital ulcers was significantly reduced in the statin group and that endothelial markers of activation were improved when comparing the statin and control groups [114]. Other studies have noted similar findings [115]. Although these results are promising, larger trials are still needed.

Thrombolytics

The role of thrombolytics in the treatment of digital ischemia and its complications has been studied on several occasions. The rationale for this is that in scleroderma, it is thought that the patients have an underlying balance towards clotting with elevated fibrinogen levels and defective TPA release [31, 116, 117], although not all groups agreed [118, 119].

At this time there is limited evidence supporting the use of fibrinolytic therapy in patients with digital ischemia, and the complications with the use of these medications can be severe. As a result they cannot be recommended for day-to-day use in the treatment of digital ischemia.

Other

Other medications that offer vascular modulating effects and that are currently still under evaluation include the tyrosine kinase inhibitors and the rho kinase inhibitors [120, 121]. Antioxidants such as allopurinol and vitamin E have surprisingly shown little benefit [122–124]. Notably, Probucol, a synthetic antioxidant, did demonstrate a significant reduction in the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s attacks when compared to controls [125]. N-acetylcysteine was recently studied prospectively in a cohort of 50 patients and reported to decrease the number of digital ulcers per year and decrease Raynaud’s attacks. It was well-tolerated in the long term with only flushing and minor headaches as side effects [126]. Other studies of anti-oxidants do not show a clear benefit for these agents, and thus we will need to wait for more data to develop clear guidelines for the use of anti-oxidants.

Botox is another reported therapeutic option for Raynaud’s and digital ischemia. Fregene and colleagues found that Botulinum toxin type A improves pain and healing in patients with Raynaud’s and scleroderma. They concluded that it is an effective treatment of vasospastic digital ischemia. Their study was limited by a small group of only 26 patients and a retrospective design [127]. Other small case series also demonstrated success with Botox in pain and healing for patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers [128]. Although promising, we await controlled trials to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of Botox in scleroderma patients with digital ischemia.

Sympathectomies

Sympathetic nerve mediated vasospasm is implicated as a major mechanism leading to digital ischemia. As a result, sympathectomies are used aimed at blocking this mechanism. Uncontrolled series of case reports suggest benefit for both Raynaud’s and for the treatment of refractory digital ulcers. Local “digital sympathectomy” done by surgical periarterial sympathectomies have also demonstrated have long term benefits in patients with digital ischemia secondary to autoimmune disease [129, 130] Hartzell and colleagues followed patients for 7.5 years and found that this intervention resulted in complete ulcer healing and decreases in the total number of ulcers in 75% of the patients in this subgroup [131]. Although it was a small group of only twenty patients, these results are promising for patients with refractory disease. Arterial revascularization is sometimes performed simultaneously and has also demonstrated success [47].

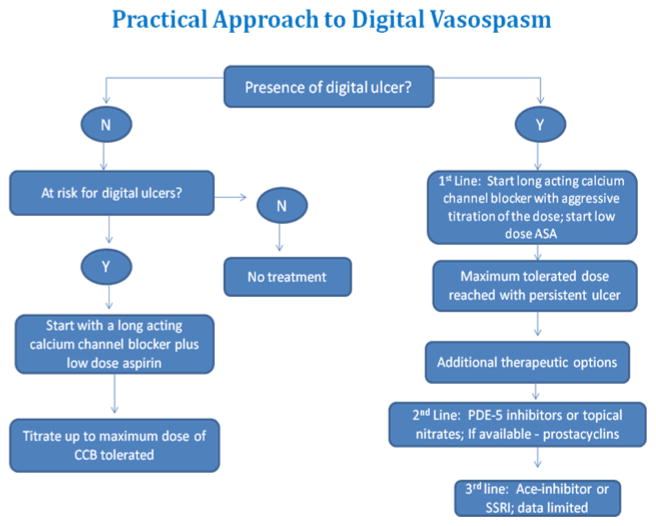

Summary on Treatment: A Practical Approach

The availability of many different therapeutic agents to treat Raynaud’s can lead to confusion when initiating therapy in the clinical setting. Accordingly, an outline of a practical approach to treatment is given based on our experience. Although specific studies are needed, we find this approach to therapy to be reasonable and effective (See Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Raynaud’s alone

In scleroderma patients with Raynaud’s without digital ulcers we first begin with supportive therapy, including the avoidance of triggers such as stress, smoking, and cold temperatures, and keeping the fingers warm with gloves. Next we begin low dose aspirin at 81 milligrams daily. At the same time, we begin a long acting calcium channel blocker, such as amlodipine, for preventative therapy and titrate it up to the highest dose tolerated needed for benefit. Toleration is limited by the possible side effects of this class of medications, including fluid retention, symptomatic hypotension, constipation, and aggravation of gastroesophogeal reflux disease. Most patients do well on low dose (e.g. amlodipine 5 mg daily) but we will titrate up the dose as needed (e.g. amlodipine 20 milligrams daily). Our goal is not to eliminate every Raynaud’s event but rather to improve the quality of life and prevent severe attacks and any progression to ischemic lesions. Thus, if a patient is not having digital lesions and reports improvement and reasonable tolerance then we continue on a calcium channel blocker alone with low dose aspirin. If the patient is still having severe symptoms once the calcium channel blocker is titrated to the maximal tolerated dose, then we will add a second agent recognizing there is few studies documenting the risk and benefits of additive therapy. Agents used include topical nitrates, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor or an SSRI based on availability and tolerance. We do use anti-oxidants but have no preference to a particular agent.

Raynaud’s with digital ulcers and severe RP

In patients with digital ulcers and severe Raynaud’s, we again stress supportive therapy, initiation of low dose aspirin, and titration of a long acting calcium channel to the highest dose tolerated. If the patient is still experiencing recurrent ulcers or moderate to severe Raynaud’s once the calcium channel blocker is at the highest dose tolerated, we then add a second agent. Usually our second agent is a topical nitrate or a phosphodiesterase inhibitor such as sildenafil; however both should not be used together as there is a risk of severe hypotension. Although not readily available in the United States, intermittent infusion of prostaglandins (e.g. Iloprost) is considered appropriate in conjunction with the calcium channel blocker. The exact interval for therapy is not well defined but previous studies suggest that benefits last about 10 weeks after a 5 day (6 hour each day) infusion of Iloprost is a period of continued benefit. If a combination of medications is not effective, and we have a nonhealing ulcer or chronic digital ischemia then we pursue a digital sympathectomy.

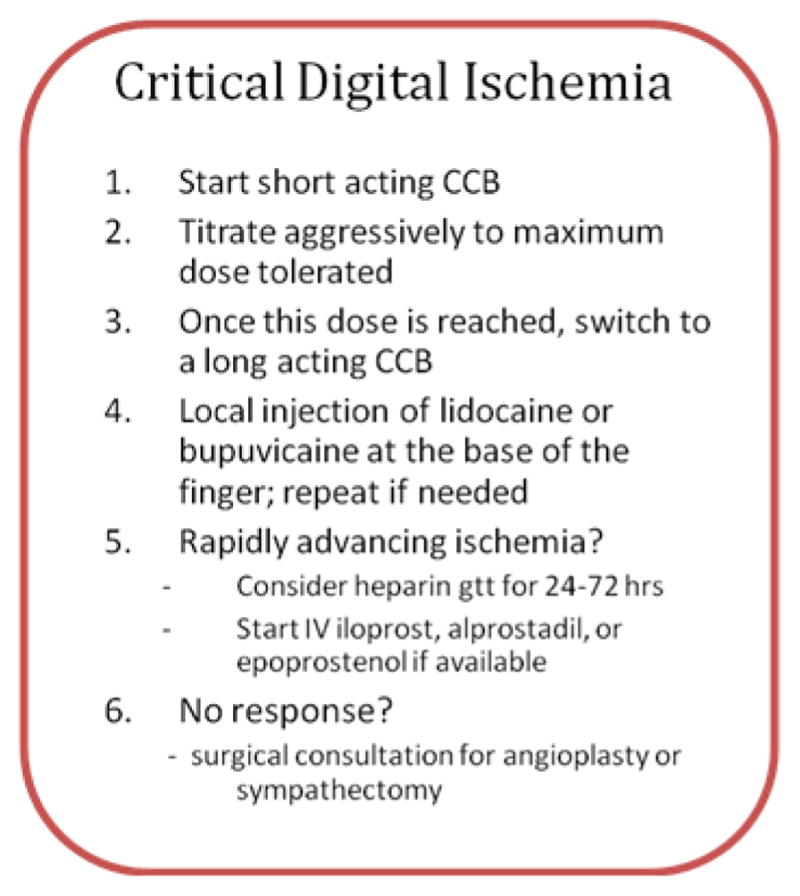

Critical ischemic event

In the setting of a critical ischemic crisis treatment must be initiated quickly and aggressively to prevent permanent tissue damage and digital loss (see Figure 3). During an ischemic crisis, irreversible vasospasm and severe pain are present. At initial presentation, a local injection of lidocaine or bupivicaine at the base of the finger can relieve pain and vasodilate rapidly. This can be repeated again if necessary. Systemic pain medication is often needed. If the patient is not on a vasodilator at the time of the crisis, then we initiate a short-acting calcium channel blocker and rapidly titrate it up to the maximal dose tolerated. Once that dose is reached, we change to a long acting calcium channel blocker at an equivalent dose if the crisis is improved. If the signs of digital ischemia continue to progress, we add a heparin drip for 24–72 hours and begin therapy with intravenous prostacyclin (epoprostenol or iloprost) continuous at low dose for about 5 days. If stable then we attempt to prevent relapse with continued calcium channel blocker alone or in combination with either a PDE inhibitor or topical nitrate. If this is still ineffective, we then recommend surgical consultation for digital sympathectomy. Doppler studies are done to investigate larger vessel disease and an MRA or angiogram is done in selected cases to localize potentially correctable arterial disease. If no larger vessel disease is found that can be corrected and the patient is not improving, then surgical sympathectomy is done. In critical ischemia with the presence of digital gangrene, it is always important to evaluate for underlying infection and add appropriate antibiotics if necessary. Surgical consultation may also be needed in this setting.

Fig. 3.

References

- 1.Wigley FM, et al. Anticentromere antibody as a predictor of digital ischemic loss in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35(6):688–93. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mawdsley AH. Patient perception of UK scleroderma services--results of an anonymous questionnaire. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(12):1573. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferri C, et al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81(2):139–53. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houtman PM, et al. Decreased nailfold capillary density in Raynaud’s phenomenon: a reflection of immunologically mediated local and systemic vascular disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44(9):603–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.44.9.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner ES, et al. Prognostic significance of anticentromere antibodies and anti-topoisomerase I antibodies in Raynaud’s disease. A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(1):68–77. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koenig M, et al. Autoantibodies and microvascular damage are independent predictive factors for the progression of Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: a twenty-year prospective study of 586 patients, with validation of proposed criteria for early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(12):3902–12. doi: 10.1002/art.24038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrick AL, et al. Anticardiolipin, anticentromere and anti-Scl-70 antibodies in patients with systemic sclerosis and severe digital ischaemia. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53(8):540–2. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.8.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker UA, et al. Clinical risk assessment of organ manifestations in systemic sclerosis: a report from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials And Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(6):754–63. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanke K, et al. Antibodies against PM/Scl-75 and PM/Scl-100 are independent markers for different subsets of systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(1):R22. doi: 10.1186/ar2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wigley FM. Clinical practice. Raynaud’s Phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(13):1001–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp013013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kallenberg CG. Raynaud’s phenomenon as an early sign of connective tissue diseases. Vasa Suppl. 1992;34:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houtman PM, et al. Diagnostic significance of nailfold capillary patterns in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. An analysis of patterns discriminating patients with and without connective tissue disease. J Rheumatol. 1986;13(3):556–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caramaschi P, et al. A score of risk factors associated with ischemic digital ulcers in patients affected by systemic sclerosis treated with iloprost. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(7):807–13. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alivernini S, et al. Skin ulcers in systemic sclerosis: determinants of presence and predictive factors of healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(3):426–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sunderkotter C, et al. Comparison of patients with and without digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: detection of possible risk factors. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(4):835–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bos CL, et al. Molecular subtypes of systemic sclerosis in association with anti-centromere antibodies and digital ulcers. Genes Immun. 2009;10(3):210–8. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sebastiani M, et al. Capillaroscopic skin ulcer risk index: a new prognostic tool for digital skin ulcer development in systemic sclerosis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(5):688–94. doi: 10.1002/art.24394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrick AL. Pathogenesis of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(5):587–96. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maricq HR, et al. Geographic variation in the prevalence of Raynaud’s phenomenon: Charleston, SC, USA, vs Tarentaise, Savoie, France. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(1):70–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeRoy EC, Medsger TA., Jr Raynaud’s phenomenon: a proposal for classification. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10(5):485–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman RR, Mayes MD. Familial aggregation of primary Raynaud’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(7):1189–91. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Susol E, et al. A two-stage, genome-wide screen for susceptibility loci in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(7):1641–6. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1641::AID-ANR30>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brennan P, et al. Validity and reliability of three methods used in the diagnosis of Raynaud’s phenomenon. The UK Scleroderma Study Group. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32(5):357–61. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.5.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suter LG, et al. The incidence and natural history of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the community. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1259–63. doi: 10.1002/art.20988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isenberg DA, Black C. ABC of rheumatology. Raynaud’s phenomenon, scleroderma, and overlap syndromes. BMJ. 1995;310(6982):795–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6982.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kallenberg CG. Early detection of connective tissue disease in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990;16(1):11–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freemont AJ, et al. Studies of the microvascular endothelium in uninvolved skin of patients with systemic sclerosis: direct evidence for a generalized microangiopathy. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126(6):561–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodnan GP, Myerowitz RL, Justh GO. Morphologic changes in the digital arteries of patients with progressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) and Raynaud phenomenon. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980;59(6):393–408. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198011000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho M, et al. Macrovascular disease and systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(1):39–43. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahaleh MB. Raynaud phenomenon and the vascular disease in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(6):718–22. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000138677.88694.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wigley FM. Vascular disease in scleroderma. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36(2–3):150–75. doi: 10.1007/s12016-008-8106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dabich L, et al. Digital arteries in patients with scleroderma. Arteriographic and plethysmographic study. Arch Intern Med. 1972;130(5):708–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasegawa M, et al. Arteriographic evaluation of vascular changes of the extremities in patients with systemic sclerosis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(6):1159–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rho YH, et al. Scleroderma associated with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26(5):369–75. doi: 10.1007/s00296-005-0011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Endo H, Hosono T, Kondo H. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in 6 patients with renal failure and systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(5):864–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Locke IC, et al. Autoantibodies to myeloperoxidase in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(1):86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyamura T, et al. Systemic sclerosis associated with microscopic polyangitis presenting with high myeloperoxidase (MPO) titer and necrotizing angitis: a case report. Ryumachi. 2002;42(6):910–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiraz S, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in systemic sclerosis. Clin Rheumatol. 1996;15(5):519–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02229659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez Ara J, et al. Progressive systemic sclerosis associated with anti-myeloperoxidase ANCA vasculitis with renal and cutaneous involvement. Nefrologia. 2000;20(4):383–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Binder C, Schattenkirchner M, Kruger K. Severe toe gangrene as an early manifestation of Wegener granulomatosis in a young patient. Z Rheumatol. 1998;57(4):227–30. doi: 10.1007/s003930050096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Handa R, Wali JP. Wegener’s granulomatosis with gangrene of toes. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25(2):103–4. doi: 10.3109/03009749609069216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.La Civita L, et al. Wegener’s granulomatosis of the elderly: a case report of uncommon severe gangrene of the feet. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(4):328. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.4.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasunuma Y, et al. Involvement of beta 2-glycoprotein I and anticardiolipin antibodies in oxidatively modified low-density lipoprotein uptake by macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107(3):569–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jara LJ, et al. Atherosclerosis and antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;25(1):79–88. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:25:1:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boin F, et al. Independent association of anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein I antibodies with macrovascular disease and mortality in scleroderma patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(8):2480–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stafford L, et al. Distribution of macrovascular disease in scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(8):476–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.8.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor MH, et al. Ulnar artery involvement in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) J Rheumatol. 2002;29(1):102–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmidt WA, et al. Colour duplex sonography of finger arteries in vasculitis and in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(2):265–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.039149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clark S, et al. Laser doppler imaging--a new technique for quantifying microcirculatory flow in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Microvasc Res. 1999;57(3):284–91. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark S, et al. Comparison of thermography and laser Doppler imaging in the assessment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Microvasc Res. 2003;66(1):73–6. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(03)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wigley FM, et al. The post-occlusive hyperemic response in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(11):1620–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780331103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray AK, et al. Noninvasive imaging techniques in the assessment of scleroderma spectrum disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(8):1103–11. doi: 10.1002/art.24645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strickland B, Urquhart W. Digital arteriography, with reference to nail dystrophy. Br J Radiol. 1963;36:465–76. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-36-427-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soila P, Wegelius U, Viitanen SM. Notes on the technique of angiography of the upper extremity. Angiology. 1963;14:297–305. doi: 10.1177/000331976301400605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takaro T, Hines EA., Jr Digital arteriography in occlusive arterial disease and clubbing of the fingers. Circulation. 1967;35(4):682–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park JH, et al. Ulnar artery vasculopathy in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29(9):1081–6. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-0906-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwon ST, et al. Peripheral arterial-bypass grafts in the hand or foot in systemic sclerosis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62(7):e216–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Connell DA, et al. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography of the hand. Radiographics. 2002;22(3):583–99. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma16583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allanore Y, et al. Hand vascular involvement assessed by magnetic resonance angiography in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2747–54. doi: 10.1002/art.22734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee VS, Lee HM, Rofsky NM. Magnetic resonance angiography of the hand. A review. Invest Radiol. 1998;33(9):687–98. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199809000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goldfarb JW, et al. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography and perfusion imaging of the hand. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(5):1177–82. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.5.1771177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herrgott I, et al. Management of cutaneous vascular complications in systemic scleroderma: experience from the German network. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28(10):1023–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wigley FM, et al. Intravenous iloprost infusion in patients with Raynaud phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis. A multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(3):199–206. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-3-199402010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Comparison of sustained-release nifedipine and temperature biofeedback for treatment of primary Raynaud phenomenon. Results from a randomized clinical trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(8):1101–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Milburn PB, Singer JZ, Milburn MA. Treatment of scleroderma skin ulcers with a hydrocolloid membrane. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(2 Pt 1):200–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wollersheim H, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of prazosin in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986;40(2):219–25. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Russell IJ, Lessard JA. Prazosin treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a double blind single crossover study. J Rheumatol. 1985;12(1):94–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paterna S, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon: effects of terazosin. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1997;45(5):215–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chotani MA, et al. Silent alpha(2C)-adrenergic receptors enable cold-induced vasoconstriction in cutaneous arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(4):H1075–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wise RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a selective alpha(2C)-adrenergic receptor blocker in recovery from cold-induced vasospasm in scleroderma patients: a single-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized crossover study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(12):3994–4001. doi: 10.1002/art.20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thompson AE, et al. Calcium-channel blockers for Raynaud’s phenomenon in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(8):1841–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1841::AID-ART322>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Riemekasten G, Sunderkotter C. Vasoactive therapies in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(Suppl 3):iii49–51. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rademaker M, et al. Comparison of intravenous infusions of iloprost and oral nifedipine in treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in patients with systemic sclerosis: a double blind randomised study. BMJ. 1989;298(6673):561–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6673.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Matucci-Cerinic M, Pietrini U, Marabini S. Local venomotor response to intravenous infusion of substance P and glyceryl trinitrate in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1990;8(6):561–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anderson ME, et al. Digital vascular response to topical glyceryl trinitrate, as measured by laser Doppler imaging, in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41(3):324–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chung L, et al. MQX-503, a novel formulation of nitroglycerin, improves the severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(3):870–7. doi: 10.1002/art.24351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rybalkin SD, et al. Cyclic GMP phosphodiesterases and regulation of smooth muscle function. Circ Res. 2003;93(4):280–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000087541.15600.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fries R, et al. Sildenafil in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon resistant to vasodilatory therapy. Circulation. 2005;112(19):2980–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.523324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lichtenstein JR. Use of sildenafil citrate in Raynaud’s phenomenon: comment on the article by Thompson et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):282–3. doi: 10.1002/art.10628. author reply 283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boin F, Wigley FM. Understanding, assessing and treating Raynaud’s phenomenon. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17(6):752–60. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000179944.35400.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Levien TL. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(7–8):1388–93. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baumhaekel M, Scheffler P, Boehm M. Use of tadalafil in a patient with a secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon not responding to sildenafil. Microvasc Res. 2005;69(3):178–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Caglayan E, et al. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition is a novel therapeutic option in Raynaud disease. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(2):231–3. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schiopu E, et al. Randomized Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial of Tadalafil in Raynaud’s Phenomenon Secondary to Systemic Sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(10):2264–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Engel G, Rockson SG. Treprostinil for the treatment of severe digital necrosis in systemic sclerosis. Vasc Med. 2005;10(1):29–32. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm579cr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pope J, et al. Iloprost and cisaprost for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000953. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Bettoni L, et al. Systemic sclerosis therapy with iloprost: a prospective observational study of 30 patients treated for a median of 3 years. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21(3):244–50. doi: 10.1007/pl00011223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Caramaschi P, et al. Does cyclically iloprost infusion prevent severe isolated pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis? Preliminary results. Rheumatol Int. 2006;27(2):203–5. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rehberger P, et al. Prostacyclin analogue iloprost influences endothelial cell-associated soluble adhesion molecules and growth factors in patients with systemic sclerosis: a time course study of serum concentrations. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89(3):245–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wigley FM, et al. Intravenous iloprost treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon and ischemic ulcers secondary to systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(9):1407–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kawald A, et al. Low versus high-dose iloprost therapy over 21 days in patients with secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon and systemic sclerosis: a randomized, open, single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(9):1830–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chung L, Fiorentino D. A pilot trial of treprostinil for the treatment and prevention of digital ulcers in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5):880–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vayssairat M. Controlled multicenter double blind trial of an oral analog of prostacyclin in the treatment of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. French Microcirculation Society Multicentre Group for the Study of Vascular Acrosyndromes. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(11):1917–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wigley FM, et al. Oral iloprost treatment in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(4):670–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199804)41:4<670::AID-ART14>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lau CS, et al. A randomised, double-blind study of cicaprost, an oral prostacyclin analogue, in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993;11(1):35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schlez A, et al. Transdermal application of prostaglandin E1 ethyl ester for the treatment of trophic acral skin lesions in a patient with systemic scleroderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(5):526–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schlez A, et al. Systemic scleroderma patients have improved skin perfusion after the transdermal application of PGE1 ethyl ester. Vasa. 2003;32(2):83–6. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.32.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Marasini B, et al. Comparison between iloprost and alprostadil in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33(4):253–6. doi: 10.1080/03009740310004711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rustin MH, et al. The effect of captopril on cutaneous blood flow in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117(6):751–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb07356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Janini SD, et al. Enalapril in Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1988;13(2):145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1988.tb00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Challenor VF. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in Raynaud’s phenomenon. Drugs. 1994;48(6):864–7. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gliddon AE, et al. Prevention of vascular damage in scleroderma and autoimmune Raynaud’s phenomenon: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor quinapril. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(11):3837–46. doi: 10.1002/art.22965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Coleiro B, et al. Treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40(9):1038–43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.9.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kahaleh MB, Osborn I, Leroy EC. Elevated levels of circulating platelet aggregates and beta-thromboglobulin in scleroderma. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(5):610–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-5-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cuenca R, et al. Platelet function study in primary Raynaud’s phenomenon and Raynaud’s phenomenon associated with scleroderma. Med Clin (Barc) 1990;95(20):761–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lau CS, et al. Increased whole blood platelet aggregation in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon with or without systemic sclerosis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1993;22(3):97–101. doi: 10.3109/03009749309099251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pamuk GE, et al. Increased circulating platelet-leucocyte complexes in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon and Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to systemic sclerosis: a comparative study. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2007;18(4):297–302. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328010bd05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Agache I, Radoi M, Duca L. Platelet activation in patients with systemic scleroderma--pattern and significance. Rom J Intern Med. 2007;45(2):183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Beckett VL, et al. Trial of platelet-inhibiting drug in scleroderma. Double-blind study with dipyridamole and aspirin. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27(10):1137–43. doi: 10.1002/art.1780271009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Korn JH, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelin receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(12):3985–93. doi: 10.1002/art.20676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Matucci-Cerinic M, Seibold JR. Digital ulcers and outcomes assessment in scleroderma. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(Suppl 5):v46–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M. Statins as immunomodulators in systemic sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1110:670–80. doi: 10.1196/annals.1423.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kuwana M. Potential benefit of statins for vascular disease in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18(6):594–600. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000245720.02512.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S, Helmii M. Statins: potentially useful in therapy of systemic sclerosis-related Raynaud’s phenomenon and digital ulcers. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(9):1801–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Del Papa N, et al. Simvastatin reduces endothelial activation and damage but is partially ineffective in inducing endothelial repair in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(7):1323–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ames PR, et al. The coagulation/fibrinolysis balance in systemic sclerosis: evidence for a haematological stress syndrome. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36(10):1045–50. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.10.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cerinic MM, et al. Blood coagulation, fibrinolysis, and markers of endothelial dysfunction in systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2003;32(5):285–95. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.50011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Matucci-Cerinic M, et al. Cutaneous and plasma fibrinolytic activity in systemic sclerosis. Evidence of normal plasminogen activation. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29(9):644–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lotti T, Campanile G, Matucci-Cerinic M. Cutaneous and plasma fibrinolytic activities are not deficient in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(5 Pt 1):813–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chung L, et al. Molecular framework for response to imatinib mesylate in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(2):584–91. doi: 10.1002/art.24221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Flavahan NA. Regulation of vascular reactivity in scleroderma: new insights into Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2008;34(1):81–7. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Herrick AL, Matucci Cerinic M. The emerging problem of oxidative stress and the role of antioxidants in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19(1):4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Herrick AL, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of antioxidant therapy in limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(3):349–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Cracowski JL, et al. Effects of short-term treatment with vitamin E in systemic sclerosis: a double blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial of efficacy based on urinary isoprostane measurement. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38(1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Denton CP, et al. Probucol improves symptoms and reduces lipoprotein oxidation susceptibility in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(4):309–15. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rosato E, et al. The treatment with N-acetylcysteine of Raynaud’s phenomenon and ischemic ulcers therapy in sclerodermic patients: a prospective observational study of 50 patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(12):1379–84. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fregene A, Ditmars D, Siddiqui A. Botulinum toxin type A: a treatment option for digital ischemia in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(3):446–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Van Beek AL, et al. Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(1):217–26. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yee AM, Hotchkiss RN, Paget SA. Adventitial stripping: a digit saving procedure in refractory Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(2):269–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kotsis SV, Chung KC. A systematic review of the outcomes of digital sympathectomy for treatment of chronic digital ischemia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(8):1788–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hartzell TL, Makhni EC, Sampson C. Long-Term Results of Periarterial Sympathectomy. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1454–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]