SUMMARY

BACKGROUND

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in children. Liver disease can be a cause of low bone mineral density. Whether NAFLD influences bone health is unknown.

AIM

To evaluate bone mineral density in obese children with and without NAFLD.

METHODS

Thirty-eight children with biopsy-proven NAFLD were matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity, height, and weight to children without evidence of liver disease from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Bone mineral density was measured by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. Age and sex-specific bone mineral density Z-scores were calculated and compared between children with and without NAFLD. After controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and total percent body fat, the relationship between bone mineral density and the severity of histology was analyzed in children with NAFLD.

RESULTS

Obese children with NAFLD had significantly (p<0.0001) lower bone mineral density Z-scores (−1.98) than obese children without NAFLD (0.48). Forty-five percent of children with NAFLD had low bone mineral density for age, compared to none of the children without NAFLD (p < 0.0001). Among those children with NAFLD, children with NASH had a significantly (p< 0.05) lower bone mineral density Z-score (−2.37) than children with NAFLD who did not have NASH (−1.58).

CONCLUSIONS

NAFLD was associated with poor bone health in obese children. More severe disease was associated with lower bone mineralization. Further studies are needed to evaluate the underlying mechanisms and consequences of poor bone mineralization in children with NAFLD.

Keywords: bone density, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry, obesity, children, adolescents, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

INTRODUCTION

Attention to skeletal health during childhood is important, as low bone mineral density (BMD) during this period has immediate and long-term consequences. In children, low BMD is associated with an increased risk of fracture.1–3 Fractures in childhood may disrupt normal activities such as school and sports, and can be detrimental to growth. In addition, low BMD in childhood has been shown to persist into early adulthood.1 This is important because peak bone accrual occurs before 20 years of age 3, and is the primary determinant of adult osteoporosis risk.4 Though several causes of low BMD in children have been identified, much remains unclear. In particular, the relationship between bone mineralization and obesity remains controversial, with numerous studies in conflict as to whether obesity increases or decreases BMD in children.5–11 Because low BMD in childhood has important consequences and obesity is very prevalent in children, it is important to identify factors underlying the discrepancy in prior studies of BMD and obesity. One potential factor related to BMD in obese children is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

NAFLD is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in children, estimated to affect up to one third of obese children.12 First reported in children in 1983 13, NAFLD was initially considered only as a spectrum of liver disease. However, further research has expanded the phenotype of NAFLD to include other health conditions, independent of obesity. For example, children with NAFLD have a worse cardiometabolic profile than equally obese children without NAFLD.14 Similarly bone health may also be an important issue that differs among obese children based on the presence or absence of NAFLD. An initial study from Turkey reported that obese children with abnormal liver ultrasonography suggestive of hepatic steatosis had lower spine BMD Z-scores than obese children with normal liver ultrasonography.15 However, this study did not include children with definitively diagnosed NAFLD by biopsy, and only examined spine BMD Z-score. Thus, we sought to determine whether children with biopsy-proven NAFLD have a lower total body BMD than obese children without NAFLD. NAFLD may be associated with poor bone mineralization, as the pathogenesis is thought to involve systemic inflammation,16 one of the known etiologies of low BMD in children.17–20 Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a severe, progressive form of NAFLD, is associated with a greater degree of inflammation.21 Thus, pediatric NAFLD, and particularly NASH, may be associated with low BMD. NAFLD is also strongly associated with obesity.12, 22 However, we hypothesize children with NAFLD have lower BMD than children without NAFLD, independent of the degree of obesity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We performed a case-control study of obese children in order to compare the BMD of children with and without NAFLD. The parent(s) or legal guardian of all subjects provided written informed consent. Written assent was obtained from all children. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of California, San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego.

Cases with NAFLD

Cases were children ages 10 to 17 years with biopsy-proven NAFLD seen at the Fatty Liver Clinic at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego. The diagnosis of NAFLD was based on liver biopsy with ≥ 5% of hepatocytes containing macrovesicular fat and exclusion of other causes of chronic liver disease, including hepatitis B (hepatitis B surface antigen), hepatitis C (hepatitis C antibody), alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (serum alpha-1 antitrypsin level and histology), autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibody, anti-smooth muscle antibody, and histology), Wilson’s disease (serum ceruloplasmin), drug toxicity, total parenteral nutrition, and chronic alcohol intake (clinical history).23 The determination of the presence or absence of steatohepatitis was based upon the features of steatosis, lobular and portal inflammation, and ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes. Children were excluded for factors that could have adversely influenced BMD including a history of a fracture within the past year, history of orthopedic surgery, or history of chronic glucocorticoid use.

Controls without NAFLD

Controls were selected from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004.24 Subjects with incomplete DXA data were excluded. In order to determine the absence of liver disease, controls had to have normal serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and be negative for hepatitis B (hepatitis B surface antigen), hepatitis C (hepatitis C antibody), and iron overload (transferrin saturation≥ 50%). In order to minimize the false classification of controls, a stringent definition of normal ALT, based upon recent biology-based thresholds for abnormal serum ALT, was used; thus boys with serum ALT >25 U/dL and girls with serum ALT >22 U/dL were excluded. 25 Controls were then matched with the cases for age, sex, race, ethnicity, height and weight.

Clinical data collection

Clinical data were obtained for each participant at a single fasting intake visit conducted at the Clinical and Translational Research Institute (CTRI) at the University of California, San Diego Medical Center (cases), or by trained NHANES personnel at sites throughout the United States (controls). Each participant’s age and gender were recorded. The race and ethnicity of the child was self-identified by the guardian present at the intake visit. Height was measured to the nearest tenth of a centimeter on a clinical stadiometer. Weight was measured on a clinical scale to the nearest tenth of a kilogram. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Phlebotomy was performed after a 12-hour overnight fast, and assays for serum ALT and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were performed using an enzymatic rate method.26

Bone and body composition measurements

All cases and controls underwent whole-body DXA scans with standard positioning.27 A fan-beam densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA) was used for cases (model QDR 4500W, software version 12.4) and controls (model QDR 4500A, software version 12.1). Both software versions include the same pediatric-specific data analysis package. Studies of similar differences in software versions in other models have not shown significant changes in body composition or BMD data.28 Total percent body fat and BMD were determined from the whole-body scan data. BMD Z-scores were calculated using race and sex-specific LMS curves based on over 1500 children.29 Low BMD for age was defined as a BMD Z-score of ≤ −2.0, as recommended by the International Society for Clinical Densitometry guidelines.30

Data analysis

Data are expressed as mean (SD) or as number and percentage. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t tests. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square tests. The BMD Z-scores of the case and control groups were compared using two-way ANCOVA, adjusting for percent body fat. The prevalence of low BMD for age (BMD z-score ≤ −2.0) in the case and control group was compared using conditional logistic regression and McNemar’s test exact method. After controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and total percent body fat, BMD Z-scores were compared among children with NAFLD, comparing those with and without NASH using linear regression. SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Study Sample

Thirty-eight obese children with biopsy-proven NAFLD were matched to 38 obese children without evidence of liver disease. Consistent with the epidemiology of NAFLD, there were more boys than girls among the groups. The demographic and clinical characteristics for cases and controls in the primary analysis are shown in Table 1. By study design cases and controls were matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity, height and weight. The mean age of the cases and controls was 13 ± 2 years. The matching for height and weight yielded the same mean BMI for both groups. Obese children with NAFLD did have significantly (p<0.001) higher mean ALT, AST, and total percent body fat than obese children without NAFLD. Of the 38 children with NAFLD, 20 had NASH.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population by Liver Status

| Characteristic | Normal Liver (N = 38) |

NAFLD (N = 38) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 13 (2) | 13 (2) |

| Sex, N (%) | ||

| Boys | 33 (86.8) | 33 (86.8) |

| Girls | 5 (13.2) | 5 (13.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity, N (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 34 (89.5%) | 34 (89.5%) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 4 (10.5%) | 4 (10.5%) |

| Weight, mean (SD), Kg | 81 (21) | 81 (21) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 159 (13) | 159 (14) |

| Body Mass Index (Kg/m2) | ||

| mean (SD) | 31 (5) | 31 (4) |

| ALT, mean (SD), U/L | 20 (3) | 133 (136)* |

| AST, mean (SD), U/L | 22 (4) | 73 (55)* |

| Body Fat, mean (SD), (%) | 39 (6) | 46 (7)* |

p < 0.001

Bone Mineral Density

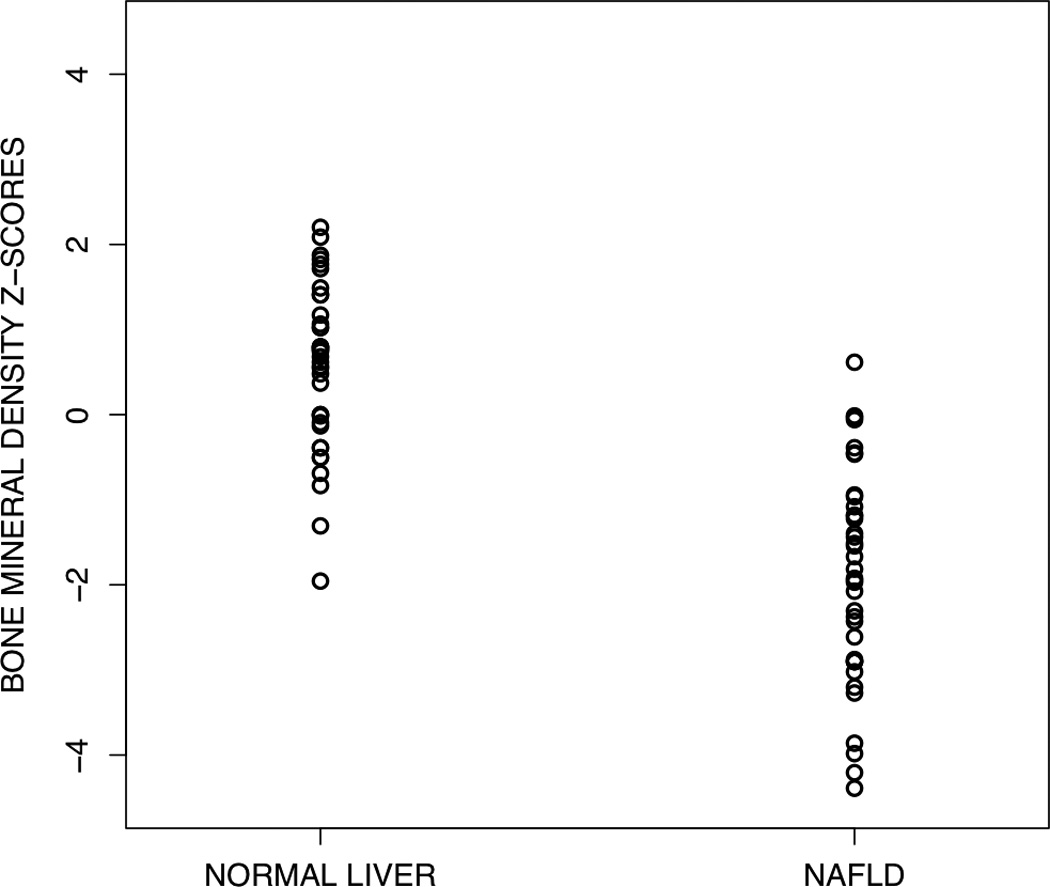

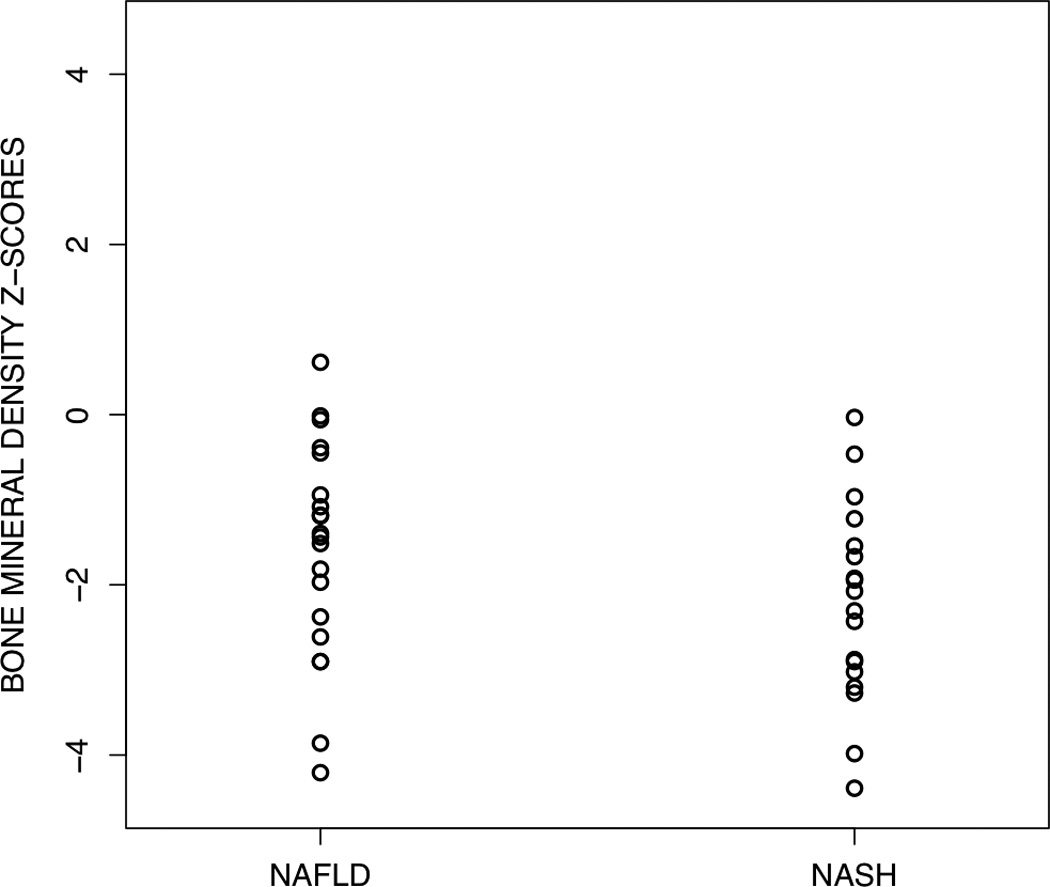

Obese children with NAFLD had a significantly (p<0.0001) lower BMD Z-score (−1.98) than obese children without liver disease (0.48), as shown in Figure 1. This relationship remained significant (p <0.0001) after adjusting for total percent body fat (mean BMD Z-score cases, −1.47; controls, −0.03). Among children with NAFLD, 45% (17/38) had BMD Z-scores ≤ −2.0, compared to none of the controls (p < 0.0001). Of the 17 children with NAFLD and BMD Z-scores < −2.0, 10 (59%) had NASH. As shown in Figure 2, among children with NAFLD, NASH was associated with the lowest BMD. Children with NASH had a significantly (p < 0.05) lower BMD Z-score (−2.37) than children without NASH (−1.58). Notably, those children who had NAFLD but did not have NASH still had a significantly lower BMD Z-score than matched controls of obese children without liver disease.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of bone mineral density Z-scores for obese children with and without NAFLD. Children with NAFLD had significantly (P <0.0001) lower BMD Z-scores than children without NAFLD.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of bone mineral density Z-scores for obese children NAFLD subdivided into those with and without NASH. Children with NASH had significantly (P <0.05) lower BMD Z-scores than children with NAFLD who did not have NASH.

DISCUSSION

We performed a case-control study of obese children with and without NAFLD in order to determine whether an association exists between NAFLD and BMD in children. Low BMD was a frequent finding among obese children with NAFLD, but not among obese children without NAFLD. This finding remained after controlling for total percent body fat. BMD also differed by the severity of histology. Children with NASH had lower BMD for age compared to children with NAFLD who did not have NASH.

In adults, the association between some forms of chronic liver disease and osteoporosis is well-established, with prevalence estimates of 1–21%, reaching as high as 50% in pre-transplant patients.31, 32 However, in contrast to the children with NAFLD in this study, in adults, markedly low BMD is rare in the absence of cirrhosis or advanced cholestatic disease.31 In addition, in the adult population much of the relationship between chronic liver disease and osteoporosis is ascribed to classic risk factors, such as advanced age, postmenopausal status, excessive alcohol consumption, hypogonadism, and the use of glucocorticoids 33 – risk factors that are not found in children with NAFLD. Furthermore, unlike many forms of chronic liver disease associated with low BMI, a risk factor for poor bone mineralization, NAFLD is strongly associated with obesity.22 Thus, though NAFLD in children may be a form of chronic liver disease associated with low BMD, considerations in evaluating this relationship are strikingly different from those in adults. Obesity is one important factor that may complicate the relationship between NAFLD and low BMD in children.

Obesity and bone mineralization in children has been studied extensively and remains a topic of great interest, as data are conflicting regarding whether obesity in this age group is detrimental or protective to bone. One reason for the controversy may be that obesity is not a unique phenotype. Rather it has become increasingly apparent that obesity is a heterogeneous condition, with significant differences existing even among children with the same degree of overweight. These differences may account for some of the discrepancies seen in the current BMD and obesity data. The distribution of body fat is one such difference among obese children that may affect bone mineral status. Visceral adipose tissue has been associated with low BMD in female adolescents.34 Inversely, subcutaneous adipose tissue has been positively associated with BMD.35 Moreover differences in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue may be related to differences in hepatic steatosis. Recent estimates suggest one-third of obese children are affected 12 and many of these children are undiagnosed.36, 37 Thus, NAFLD represents a common and under-recognized difference among obese children that may contribute to the inconsistencies in the assessment of BMD in this group.

Given the high prevalence of NAFLD and the adverse consequences of low BMD in childhood, understanding the mechanisms underlying the relationship between NAFLD and low BMD is important to prevent bone loss in this potentially vulnerable population. Why children with NAFLD, and particularly NASH, have low BMD compared to equally obese children without NAFLD is unknown, but, as hypothesized in other forms of chronic liver disease 38, 39, may involve the inflammatory response. Systemic inflammation is well known to contribute to low BMD in several disease states.17, 19, 20 The inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6, and interleukin-1 all increase osteoclast activity by up-regulating receptor activator of nuclear factor kβ ligand (RANKL).40 In addition, TNF-α inhibits osteoblast differentiation and promotes osteoblast apoptosis.41 These cytokines have been implicated in the pathogenesis of NAFLD as well.16 NASH is thought to develop in part from this persistent inflammatory state, via the activation of hepatic stellate and dendritic cells.42, 43 Thus, the presence of inflammation in NAFLD may contribute to the association between NAFLD and low BMD found here. However, the complete pathophysiology is likely to be complex and multifactorial. In order for future studies to elicit a mechanistic understanding of this association, they will need to have rigorous, accurate phenotyping of study subjects to include assessment of both the presence or absence of NAFLD and to determine disease severity based upon features such as steatohepatitis.

The strengths of this study were the inclusion of children with rigorously defined biopsy-proven NAFLD and the use of a control group that was matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity, height and weight. The large number of participants available in NHANES allowed for precise matching of cases and controls. This study did have limitations. Due to the use of NHANES for control participants, controls were determined to not have NAFLD based upon serum ALT activity, rather than biopsy or imaging. However, we used recently defined, biologically-based values for normal ALT, which are more stringent than the ALT values that are in widespread clinical use.25 Thus, the likelihood of falsely classifying a child in the control group as not having liver disease was relatively small. Furthermore, the misclassification of controls would favor the null hypothesis, rather than the large difference in BMD found in this study. In addition, the BMD of cases and controls was measured on different densitometers. However, all measurements were made using the same fan-beam technology from the same manufacturer and model series. Though the use of different machines may have produced small differences in BMD between cases and controls, it is very unlikely that the large difference seen in this study could be explained solely on this basis. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study allowed only for association rather than causation. Moreover, these data cannot be used to determine the timing of bone mineralization in obese children with or without NAFLD.

CONCLUSIONS

Poor bone mineralization was common among children with biopsy-proven NAFLD, but not among obese children without liver disease. Importantly, children with more severe histology had worse bone mineral status than children with more mild abnormalities. These differences persisted after controlling for total percent body fat. This relationship may be an important etiology underlying the discrepancy regarding whether obese children have higher or lower BMD than normal weight children, as many obese children have undiagnosed NAFLD. In addition, this finding has important implications for the long-term skeletal health of the child with NAFLD, and particularly the child with NASH. Whether fracture rates are higher in this population is unknown, though we have observed several clinically significant fractures among children with NAFLD in our clinic. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine whether rates of fracture are indeed higher in this population. Whether bone density screening should be recommended for children with NAFLD or NASH, and what interventions should be taken to improve low BMD in this population, await further research.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported in part by NHLBI T32RR023254 and by UL1RR031980 from the NCRR for the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at UCSD. The funders did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- BMC

bone mineral content

- BMD

bone mineral density

- DXA

dual energy x-ray absorptiometry

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Specific Author Contributions

Study concept and design: Pardee, Dunn, Schwimmer

Acquisition of Data: Pardee, Schwimmer

Statistical Analysis: Dunn

Interpretation of Data: Pardee, Schwimmer

Drafting of the manuscript: Pardee, Dunn

Critical revision of the manuscript: Schwimmer

Final Approval: Pardee, Dunn, Schwimmer

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheng S, Xu L, Nicholson PH, et al. Low volumetric BMD is linked to upper-limb fracture in pubertal girls and persists into adulthood: a seven-year cohort study. Bone. 2009;45(3):480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark EM, Ness AR, Bishop NJ, Tobias JH. Association between bone mass and fractures in children: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(9):1489–1495. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boot AM, de Ridder MA, van der Sluis IM, van Slobbe I, Krenning EP, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM. Peak bone mineral density, lean body mass and fractures. Bone. 2010;46(2):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285(6):785–795. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Timpson NJ, Sayers A, Davey-Smith G, Tobias JH. How does body fat influence bone mass in childhood? A Mendelian randomization approach. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(3):522–533. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stettler N, Berkowtiz RI, Cronquist JL, et al. Observational study of bone accretion during successful weight loss in obese adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(1):96–101. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pietrobelli A, Faith MS, Wang J, Brambilla P, Chiumello G, Heymsfield SB. Association of lean tissue and fat mass with bone mineral content in children and adolescents. Obes Res. 2002;10(1):56–60. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goulding A, Taylor RW, Jones IE, Manning PJ, Williams SM. Spinal overload: a concern for obese children and adolescents? Osteoporos Int. 2002;13(10):835–840. doi: 10.1007/s001980200116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janicka A, Wren TA, Sanchez MM, et al. Fat mass is not beneficial to bone in adolescents and young adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):143–147. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wetzsteon RJ, Petit MA, Macdonald HM, Hughes JM, Beck TJ, McKay HA. Bone structure and volumetric BMD in overweight children: a longitudinal study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(12):1946–1953. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollock NK, Laing EM, Baile CA, Hamrick MW, Hall DB, Lewis RD. Is adiposity advantageous for bone strength? A peripheral quantitative computed tomography study in late adolescent females. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(5):1530–1538. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1388–1393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran JR, Ghishan FK, Halter SA, Greene HL. Steatohepatitis in obese children: a cause of chronic liver dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78(6):374–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwimmer JB, Pardee PE, Lavine JE, Blumkin AK, Cook S. Cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Circulation. 2008;118(3):277–283. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirgon O, Bilgin H, Tolu I, Odabas D. Correlation of insulin sensitivity with bone mineral status in obese adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75(2):189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai D, Yuan M, Frantz DF, et al. Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-beta and NF-kappaB. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):183–190. doi: 10.1038/nm1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compeyrot-Lacassagne S, Tyrrell PN, Atenafu E, et al. Prevalence and etiology of low bone mineral density in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(6):1966–1973. doi: 10.1002/art.22691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnham JM, Shults J, Semeao E, et al. Whole body BMC in pediatric Crohn disease: independent effects of altered growth, maturation, and body composition. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(12):1961–1968. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubner SE, Shults J, Baldassano RN, et al. Longitudinal assessment of bone density and structure in an incident cohort of children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):123–130. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard MB. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in children: impact of the underlying disease. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 2):S166–S174. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2023J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wieckowska A, Papouchado BG, Li Z, Lopez R, Zein NN, Feldstein AE. Increased hepatic and circulating interleukin-6 levels in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(6):1372–1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Rauch JB, Behling C, Newbury R, Lavine JE. Obesity, insulin resistance, and other clinicopathological correlates of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr. 2003;143(4):500–505. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: definition and pathology. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21(1):3–16. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwimmer JB, Dunn W, Norman GJ, et al. SAFETY study: alanine aminotransferase cutoff values are set too high for reliable detection of pediatric chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(4):1357–1364. 1364 e1–1364 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Survey Examination and Laboratory Protocol. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Binkovitz LA, Henwood MJ. Pediatric DXA: technique and interpretation. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(1):21–31. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0153-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vozarova B, Wang J, Weyer C, Tataranni PA. Comparison of two software versions for assessment of body-composition analysis by DXA. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):229–232. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalkwarf HJ, Zemel BS, Gilsanz V, et al. The bone mineral density in childhood study: bone mineral content and density according to age, sex, and race. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(6):2087–2099. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon CM, Bachrach LK, Carpenter TO, et al. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry interpretation and reporting in children and adolescents: the 2007 ISCD Pediatric Official Positions. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11(1):43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leslie WD, Bernstein CN, Leboff MS. AGA technical review on osteoporosis in hepatic disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(3):941–966. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakchbandi IA, van der Merwe SW. Current understanding of osteoporosis associated with liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6(11):660–670. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collier J. Bone disorders in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2007;46(4):1271–1278. doi: 10.1002/hep.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell M, Mendes N, Miller KK, et al. Visceral fat is a negative predictor of bone density measures in obese adolescent girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1247–1255. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gilsanz V, Chalfant J, Mo AO, Lee DC, Dorey FJ, Mittelman SD. Reciprocal relations of subcutaneous and visceral fat to bone structure and strength. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3387–3393. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley MR, Bass NM, Rosenthal P, Merriman RB. Underdiagnosis of pediatric obesity and underscreening for fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome by pediatricians and pediatric subspecialists. J Pediatr. 2005;147(6):839–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fishbein M, Mogren J, Mogren C, Cox S, Jennings R. Undetected hepatomegaly in obese children by primary care physicians: a pitfall in the diagnosis of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2005;44(2):135–141. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diez Ruiz A, Santos Perez JL, Lopez Martinez G, Gonzalez Calvin J, Gil Extremera B, Gutierrez Gea F. Tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 in alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcohol Alcohol. 1993;28(3):319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez-Calvin JL, Gallego-Rojo F, Fernandez-Perez R, Casado-Caballero F, Ruiz-Escolano E, Olivares EG. Osteoporosis, mineral metabolism, and serum soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor p55 in viral cirrhosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(9):4325–4330. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kudo O, Fujikawa Y, Itonaga I, Sabokbar A, Torisu T, Athanasou NA. Proinflammatory cytokine (TNFalpha/IL-1alpha) induction of human osteoclast formation. J Pathol. 2002;198(2):220–227. doi: 10.1002/path.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilbert L, He X, Farmer P, et al. Expression of the osteoblast differentiation factor RUNX2 (Cbfa1/AML3/Pebp2alpha A) is inhibited by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(4):2695–2701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connolly MK, Bedrosian AS, Mallen-St Clair J, et al. In liver fibrosis, dendritic cells govern hepatic inflammation in mice via TNF-alpha. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(11):3213–3225. doi: 10.1172/JCI37581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nieto N. Oxidative-stress and IL-6 mediate the fibrogenic effects of [corrected] Kupffer cells on stellate cells. Hepatology. 2006;44(6):1487–1501. doi: 10.1002/hep.21427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]