Abstract

Tissue engineering promises to restore or replace diseased or damaged tissue by creating functional and transplantable artificial tissues. The development of artificial tissues with large dimensions that exceed the diffusion limitation will require nutrients and oxygen to be delivered via perfusion instead of diffusion alone over a short time period. One approach to perfusion is to vascularize engineered tissues, creating a de novo three-dimensional (3D) microvascular network within the tissue construct. This significantly shortens the time of in vivo anastomosis, perfusion and graft integration with the host. In this study, we aimed to develop injectable allogeneic collagen-phenolic hydroxyl (collagen-Ph) hydrogels that are capable of controlling a wide range of physicochemical properties, including stiffness, water absorption and degradability. We tested whether collagen-Ph hydrogels could support the formation of vascularized engineered tissue graft by human blood-derived endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in vivo. First, we studied the growth of adherent ECFCs and MSCs on or in the hydrogels. To examine the potential formation of functional vascular networks in vivo, a liquid pre-polymer solution of collagen-Ph containing human ECFCs and MSCs, horseradish peroxidase and hydrogen peroxide was injected into the subcutaneous space or abdominal muscle defect of an immunodeficient mouse before gelation, to form a 3D cell-laden polymerized construct. These results showed that extensive human ECFC-lined vascular networks can be generated within 7 days, the engineered vascular density inside collagen-Ph hydrogel constructs can be manipulated through refinable mechanical properties and proteolytic degradability, and these networks can form functional anastomoses with the existing vasculature to further support the survival of host muscle tissues. Finally, optimized conditions of the cell-laden collagen-Ph hydrogel resulted in not only improving the long-term differentiation of transplanted MSCs into mineralized osteoblasts, but the collagen-Ph hydrogel also improved an increased of adipocytes within the vascularized bioengineered tissue in a mouse after 1 month of implantation.

Keywords: Collagen hydrogels, Vascularization, Tissue engineering

1. Introduction

Creating large functional and transplantable tissues for organ replacement have failed in the past because of the limited diffusion distance of oxygen and nutrients to a few hundred micrometers. This can lead to necrosis at the central region of the large-sized tissue-engineered or highly vascularized tissues [1–3]. Host blood vessels usually take days or weeks to invade the centre of engineered tissue, so during this process an insufficient vascular supply leads the tissue to nutrient depletion and ischemia, which can compromise cell viability and function [2,4,5]. To overcome this problem, nutrients and oxygen need to be delivered via perfusion instead of diffusion alone [3]. Aside from current strategies promoting angiogenesis from the host, an alternative concept is to pre-vascularize a tissue that creates a vascular network within the tissue construct prior to implantation [6]. Vascularization generally refers to the formation of an in vitro well-connected microvessel network within an implantable tissue construct through vasculogenesis. Following implantation, this vasculature can rapidly anastomose with the host and enhances tissue survival and function [1,3]. Furthermore, microfabrication techniques have been applied as a means to control space and direct the growth of vascular networks in vitro [7–10]; however, these pre-engineered networks are too simple to grow and reform in response to specific physiological demands from the organs they are supporting in the host [1,11]. Therefore, we have demonstrated the formation of vascular networks, de novo, from encapsulating endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) in the liquid matrix prior to gelation, and injected or implanted subcutaneously in immune-deficient mice to form a 3D cell-laden vascularized construct within one week [12–14]. ECFCs circulating in peripheral blood participate in the formation of new blood vasculature and have been a promising source in producing non-invasive large quantities of autologous endothelial cells for clinical use [13,15]. Together with suitable support from scaffolds, MSCs can function as pericytes to promote vessel formation and maturation through secretion of specific pro-angiogenic cytokines [14,16]. Meanwhile, transplanted ECFCs provided critical angiocrine factors needed to preserve MSC as viable and further support ultimately long-term differentiation of transplanted MSCs to osteoblasts to form vascularized engineered bone tissue constructs by inducing specific stimulants of BMP-2 [12].

A critical requirement for engineering a tissue is the use of a suitable scaffold to mimic structural and functional properties of the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) that includes providing appropriate binding sites for cell–material interactions, mechanical properties to maintain cell function prior to host remodeling without negatively impacting the development of the capillary network, and biodegradation that matches the deposition rate of new extracellular matrix protein by the host [6]. Over the last few years, a variety of natural-based hydrogels [17] have been shown to be compatible with endothelial cell-mediated vascular morphogenesis, including natural materials (type I collagen gel [18–22], fibrin gels [19,23], Matrigel [12,24]), semi-synthetic materials, i.e. modified natural material (photo-crosslinkable methacrylated gelatin [10,14,16] and enzymatic-crosslinkable tyramine-modified gelatin hydrogels [25,26]). However, there still remains a significant discrepancy in how physicochemical properties of scaffolds, such as mechanical properties, density of cell-adhesive ligand (RGD) or degradable sites (MMP) of scaffolding affect the angiogenic potential of endothelial cells (EC) to form functional blood vessels in vivo. RGD-mediated and integrin-dependent bindings on native collagen nanofibrins support the development of sufficient matrix-transduced tensional forces necessary for EC sprouting and tube formation [27]. The stiffness of self-assembled collagen matrices affects cell spreading, migration, growth and matrix remodeling, all of which are critical components of vascular formation [20,28]. Varying collagen concentration of polymerized 3D collagen gels that alter matrix stiffness and fibril density has been shown to alter EC lumen size and tube length [18–20,28,29], but in this case the RGD is dependent on collagen concentrations. These issues raised the difficulties of discerning which matrix properties induce EC responses. The aforementioned results provide initial evidence that specific collagen matrix physical properties are important parameters in determining the ability of matrices to guide vessel formation. However, most studies [19,26,28,29] have not been followed up with investigations addressing whether physicochemical properties of matrices impact upon vessel formation and if they further influence the success of creating vascularized tissue construct in vivo, which would lead to more clinically relevant cell-based therapies.

So far, there have only been a few successful thick vascularized engineered tissue constructs, because the lack of proper scaffolding material that cannot only support vascularization in a short time period, but also directs transplanted MSCs differentiation into a specific lineage, remains a major challenge [4,5,11]. Although collagen offers an ideal injectable gel system in vascular tissue engineering, the extensive contraction, poor stiffness, rapid degradation and temperature instability of collagen gels limit their practical applications in regenerating and engineering living tissues, such as adipose or bone tissue grafts [22,30]. Thus, the development of collagen-based scaffolds that can maintain the mechanical integrity of the tissue, support the development and growth of complex microvessel networks, while simultaneously improving the mature differentiation of stem cells to meet the functional requirements of specific tissue, is more desirable. In response to these limitations, we aimed to develop chemical functionalization of natural-derived ECM proteins, i.e. injectable collagen-Ph hydrogels, which are capable of having controlled physicochemical properties over a wide range. To test the biocompatibility and potential for applications in tissue engineering, the ECFCs and MSCs were seeded on or inside collagen-Ph hydrogels to study the cell adhesion, proliferation and function in vitro. Pre-clinical studies with immunodeficient mice were carried out and demonstrated that functional human vascular networks can be generated in situ by means of post-injectable enzymatic polymerization that enables tuning of the final vascular density inside the collagen-Ph hydrogel constructs. We hypothesized that this cell-laden collagen-Ph construct would rapidly anastomose with host vasculature and improve vascularization and survival of the host abdominal muscle defect with the formation of ECFC-lined vascular networks throughout and in-between skeletal muscle fibers in the host. Finally, feasibility studies toward an ultimate goal of bioengineered 3D vascularized tissue grafts were developed and characterized. Our studies importantly suggest the capacity of ECM-based cell delivery hydrogel systems to incorporate physicochemical cues to modulate vessel formation and further evaluate the feasibility to engineer vascularized transplantable artificial tissues in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Extraction of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels from epidermis

Before collagen extraction, murine epidermal tissue was cut into small pieces (<25 mm2) and soaked into 70% ethanol for 2 min at a skin/solution ratio of 1:4 (w/v) to remove debris and sterile murine epidermis at room temperature. Collagen was extracted by incubating small pieces of tissue with a skin/pepsin (Sigma–Aldrich)/0.5 M acetic acid at ratio of 1 g:0.06 g: 30 ml at 4 °C with continuously overnight shaking. After 48 h, the supernatants of the extracted solutions were collected by centrifugation at 11,700g for 10 min at 4 °C, and then salted out by adding NaCl to a final concentration of solution at 3 M followed by centrifugation under the same conditions. The precipitate was re-dissolved in 0.5 M acetic acid of original volume before centrifugation, and then dialyzed against 0.1 M acetic acid for 10 times of dialyzed solution for 1 day at 4 °C. Before freeze-dried, the resultant collagen was further to dialyze against distilled water for 100 times of dialyzed solution to remove all salts out. The extracted murine collagen samples were weighed and the extraction yield calculated, then were subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS), amino acid analyzer (Waters, Model Workstation, USA), measurement of hydroxyproline (hyp) content [31], and tested for effects on cell behavior.

2.2. Synthesis and characterization of murine collagen-tyramine (murine collagen-Ph) conjugates

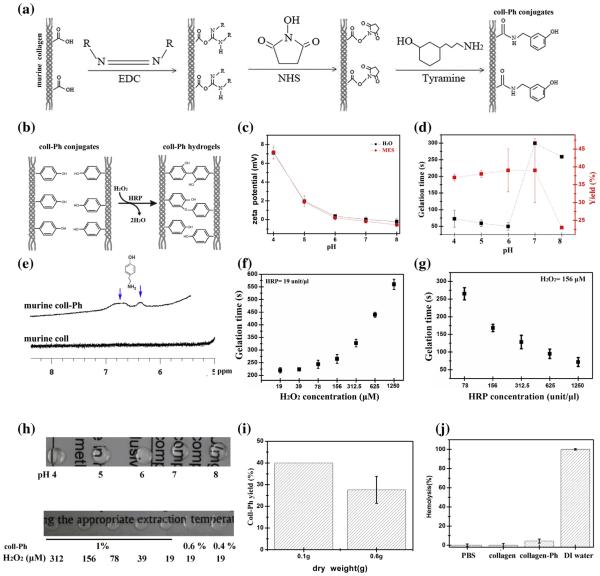

Murine collagen-phenolic hydroxyl (murine collagen-Ph) derivatives possessing phenolic hydroxyl (Ph) groups were synthesized by combining murine collagen and tyramine hydrochloride via the carbodiimide-mediated condenzation of the carboxyl groups of collagen and the amino groups of tyramine, resulting in the binding of a phenolic hydroxyl (Ph) group to the carboxyl group, shown in Fig. 2a. The freeze-dried murine collagen (0.05 g) was dissolved as 0.25% (w/v) in 40 ml of 0.1 M HCl aqueous solution at 4 °C overnight. Adding morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES, Sigma– Aldrich) of 0.781 g into murine collagen solutions and then adjusting pH to 4–8 by adding various amounts of 0.1 N NaOH solutions at 4 °C. Murine collagen-Ph conjugates was then prepared by activating the carboxyl groups of collagen with 0.135 g of EDC and 0.032 g of NHS followed by reacting with tyramine (0.167 g) in MES buffer (pH 4–8) (Fig. 2c) for 24 h at 4 °C, and then the reaction was stopped by addition of 0.1 N NaOH solutions to have a pH above 7.2 for 30 min. The resultant polymer solution was dialyzed against deionized water using an ultrafiltration membrane (MWCO: 3500) until the absorbance peak at 275 nm due to residual tyramine was unde-tectable in the filtered solution by ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrometer (Thermo). Finally, to obtain the powder form of murine collagen-Ph conjugates, the murine collagen solution was freeze-dried for 3 days at −50 °C and 50 mTorr.

Fig. 2.

Synthesis and characterization of murine collagen-Ph (coll-Ph) conjugates. (a) Reaction scheme for the synthesis of collagen-Ph conjugates. (b) Formation of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels by enzyme-catalyzed oxidation through the addition of HRP and H2O2 into collagen-Ph solutions. (c) Evolution of f potential measurements of extracted murine collagen dissolved in ddH2O and MES buffer at different pHs. (d) Effects of MES buffers with different pHs on the gelation time and yield of murine collagen-Ph conjugates. HRP and H2O2 concentrations are fixed at 78 units/μl and 78 μM, respectively. (e) 1H NMR of unmodified collagen and collagen-Ph conjugates dissolved in D2O. Dependence of gelation time of 1% (w/v) of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels on variable concentrations of (f) H2O2 and (g) HRP (n = 3). (h) A photograph of 1% (w/v) murine collagen-Ph solution synthesized at different pHs of MES buffers after adding 78 units/μl of HRP and 78 μM of H2O2 (upper row). A photograph of murine collagen-Ph solutions with various amounts of collagen-Ph and H2O2 at fixed HRP of 78 unit/μl (lower row). (i) Yields of collagen-Ph conjugate synthesized from different amounts of dried murine collagen (n = 5). (j) Hemolysis test of unmodified collagen and collagen-Ph conjugates (n = 3). A normal saline solution was set as a negative control, while distilled water was set as a positive control. The data are presented as average values ± standard deviation (n = 3–5).

In order to optimize conditions for chemical immobilization of tyramine on collagen, surface zeta-potential analysis (Malvern Zeta Nanosizer) was performed on murine collagen solutions dissolved in HCl and MES buffers. The conjugation of Ph groups to murine collagen was then investigated as a function of pH by measuring gelation time and conjugate yield. The conjugates were then dissolved at 1 mg per ml in D2O and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer at 4 °C to obtain an indication of how much tyramine was immobilized in the murine collagen conjugates. The exact amount of tyramine bounded to murine collagen was quantified [25,32,33] by dissolving the tyramine-substituted collagen as a 0.1% (w/w) solution in distilled water and measuring the absorbance at 275 nm on an ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrometer and estimating the content of introduced Ph groups using a calibration curve of different concentrations of tyramine hydrochloride in distilled water. Unmodified murine collagen serves as the control.

2.3. Hydrogel formation and gelation time

For hydrogel formation, freshly prepared solutions of enzyme horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (10 μl of each) (both from Sigma–Aldrich) at the indicated concentrations in calcium- and magnesium-free Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) were added to 80 ll of aqueous solution of 1.25% (w/v) murine collagen-Ph in Ca/Mg-free DPBS and mixed (step 2, Fig. 2b), then the solution was examined by gelation time, which starts to go viscous (Fig. S10).

2.4. Hydrogel characterization

Hemolysis assay were performed with adding 100 ll of whole blood of rabbits into 10 mL solution containing 0.1% (w/v) murine collagen-Ph conjugates in PBS, and incubated at 37 °C under mild shaking for 1 h. The samples were then centrifuged at 2000g for 5 min, and the concentration of hemoglobin with absorbance at 550 nm in the supernatant was determined by UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy. A negative control of PBS solution and a positive control of distilled water were also detected for comparison.

Rheological characteristics were carried out with a rheometer (AR-G2, TA instruments) operating with parallel plate geometry (25 mm diameter plates) at room temperature in the oscillatory mode. One day before measurement, rat tail collagen gels and murine collagen-Ph hydrogels were made, and immersed into PBS at room temperature. For each measurement, murine collagen-Ph hydrogels with varying concentrations of murine collagen-Ph conjugates, HRP and H2O2 were applied to the bottom plate and the upper plate was lowered to a measurement gap of 1.4 mm. A frequency of 10 rad/s and the strain of 1% were applied in the analysis to maintain the linear viscoelastic behavior. The measurement was continued until the storage modulus recorded reached a plateau value.

For swelling tests, murine collagen-Ph hydrogels crosslinked at desired conditions were prepared as described above. Each hydrogel was immersed in 1 ml of PBS overnight at 37 °C. Next day the swollen hydrogels were weighed and then lyophilized. The swelling ratio was taken as the extent of water absorption (swollen mass minus dried mass) divided by the dried mass (after lyophilization).

The in vitro enzymatic degradation properties of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels with different cross-linked degrees were determined in DPBS containing collagenase type I (0.2 U/ml, Sigma Aldrich) for 3–9 h at 37 °C. The percentage of mass loss was determined at different time points by the ratio of the weight to the original weight. in vivo degradation of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels were evaluated by injecting a murine collagen-Ph hydrogel (200 μl) into the subcutaneous space on the back of a six-week-old BALB/cAnN.Cg-Foxnlnu/CrlNarl nude mice. Each nude mouse carried two hydrogels on each side of its back. Rat tail type-I collagen gel (3 mg/mL in DPBS; pH = 7.4; 200 μl; BD Biosciences) served as a control [34–36]. After 7 days, the implants were taken out, imaged and weighed to determine the degradation degree of each hydrogel.

The nanostructures of the murine collagen-Ph hydrogels were observed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) at 15 kV as previously described.

2.5. Cell culture

ECFCs and MSCs were isolated from human cord blood and bone marrow, respectively, as described previously [13,37,38]. ECFCs were cultured on collagen type I (5 μg/cm2, BD)-coated tissue culture plates in endothelial basal medium (EBM-2; Lonza) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (20%, Hyclone), SingleQuots (except for hydrocortisone) (Lonza), and 1x penicillin–streptomycin (PS) (Invitrogen), called as ECFC-medium. MSCs were cultured on uncoated plates using mesenchymal stem cell growth medium (MSCGM) (Lonza) with FBS (10%), 1x PS and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (10 ng/mL, Millipore), called as MSC-medium. ECFCs and MSCs between passages 8 and 10 were used for all of the experiments. The number of attached or proliferated cells was assessed by MTS assay (Sigma–Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.6. Cell attachment, viability, proliferation and spreading assays on hydrogels

Murine collagen-Ph conjugates were dissolved in calcium- and magnesium-free DPBS at 1.25% (w/v) as stock solution. To this solution, 1/10 volume of a concentrated HRP, H2O2 solution and calcium- and magnesium-free DPBS were added, resulting in a final concentration of 0.4–1% (w/v) of murine collagen-Ph conjugates, 78 unit/μl of HRP and 19–312.5 μM of H2O2 in DPBS. Before gelation, the mixture (300 μl/well) was poured into each well in a 24-well plate, and collagen-Ph hydrogels were formed less than 10 min within each well at 37 °C. Rat tail collagen type-I gels were chosen as control gels to culture cells. Rat tail collagen solution (3.5 mg/ml, BD Bioscience) were mixed with 10× PBS, 1 N NaOH, 25 mM HEPES and sterile distilled water at a final concentration of 3 mg/ml at pH 7, and purred the mixture (300 μl/well) into each well in a 24-well plate at 37 °C for 2 h to form rat tail collagen gels. In order to understand the effects of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels cross-linked with different protein (0.4–1% (w/v)) and H2O2 (0.31–2.5 mM) concentrations at 78 unit/μl of HRP on cell adhesion, proliferation, viability and spreading, ECFCs or MSCs were seeded onto per hydrogel, and cultured for suitable culturing time period at 37 °C and in 5% CO2. ECFCs or MSCs were seeded onto per hydrogel at 4 × 104/cm2 and incubated for 4 h to allow for cell attachment. ECFCs or MSCs were seeded onto per hydrogel at 2 × 104/cm2 and incubated for 48 h to allow for cell proliferation. After an appropriate incubation period, the viability of cells on the gels was determined using Live/Dead staining kits (Invitrogen). The green-stained cells (live cells) and red-stained cells (dead cells) were imaged under a fluorescent microscope. Cells in ten randomly selected fields of view under 200x magnification were counted and analyzed by using ImageJ software. The attachment and proliferation was determined by live cell (green-stained cells) divided with seeded cells in the beginning. The viability and proliferation was determined by live cell (green-stained cells) divided with the sum of live (green-stained cells) and dead cells (red-stained cells). The spreading area and length occupied by each cell was measured using ImageJ software.

2.7. Viability and spreading of cells encapsulated in murine collagen-Ph hydrogels

For three-dimensional (3D) monoculture studies, ECFCs and MSCs were encapsulated at 4 × 106 cells/ml within 200 μl of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels with 0.6–1% (w/v) of murine collagen-Ph conjugates, 78 unit/μl of HRP and 19–312.5 μM of H2O2, and rattail collagen gels (control). Following 24–48 h of culture, viability of ECFCs and MSCs was measured using the Live/Dead staining kits (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The green-stained cells (live cells) and red-stained cells (dead cells) were imaged at ten randomly fields under fluorescent microscope under 100x magnification. For 3D co-culture studies, ECFCs and MSCs (4 × 106 cells/ml total; 2:3 ECFC/MSC ratio [24,35,39]) were resuspended in 200 μl of murine collagen-Ph solutions, and then concentrated H2O2 (19 μm) and HRP (78 unit/μl) were added to form 1% (w/v) murine collagen-Ph hydrogels. Cells in five randomly selected fields of view under 200x magnification were counted and analyzed by using ImageJ software. The viability and proliferation was determined by live cell (green-stained cells) divided with the sum of live (green-stained cells) and dead cells (red-stained cells).

2.8. Transmigration assay

Transwell inserts (6.5 mm diameter, 8.0 μM pore size; BD) were coated with 20 μl 0.4–1% (w/v) murine collagen-Ph hydrogels formed using 78 unit/μl HRP and different concentrations of H2O2. After 4 h, wash hydrogels with PBS several times to remove all collagenase type I and then seeded cells on the top of gels. ECFCs (1 × 104 cells in 100 μl of EBM-2, with 5% FBS) or MSCs (1 × 104 cells in 100 μl of MSCGM, with 5% FBS) were added to the top compartment of the transwell inserts. Inserts were then transferred into 24-well plates containing 1 mL/well of ECFC-medium or MSC-medium. After 48 h, transmigrated cells were visualized on the bottom side of the insert membrane and counted cell numbers by randomly taking 5–7 images by microscopy in 200× magnification.

2.9. in vivo cell engraftment assay

Male six- to eight-week-old BALB/cAnN.Cg-Foxnlnu/CrlNarl nude mice were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Taiwan. All procedures involving animals and their care were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Vasculogenesis was evaluated in vivo using our xenograft model as described previously [24,38,39]. Briefly, for murine collagen-Ph hydrogels, ECFCs and MSCs (2 × 106 total; 2:3 ECFC/MSC ratio) were suspended in 250 μl of murine collagen-Ph solution, and then concentrated H2O2 and HRP were added to give final concentrations of 0.4–1% (w/v) collagen-Ph conjugates, 78 units/μl of HRP, and 19–78 μM of H2O2. The mixture was then injected subcutaneously into mice and the hydrogel formed inside the mouse within 3 min. Rat tail type-I collagen gel (3 mg/ml in PBS, pH 7.4) (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) containing the same number of cells served as controls. In addition, cell-laden constructs were also implanted into anesthetized mice by creation of a 2 mm × 2 mm defect in the anterior abdominal wall of the mice. On BMP-2 induced subcutaneous mice model experiments [12], supplements were added to the cell laden collagen-Ph pre-polymer prior to implantation: BMP-2 (R&D Systems; 2 μg/implant). Directly after sacrifice at indicated time interval, implants with the surrounding tissues were retrieved and fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde solution (pH 7.2–7.4; Sigma–Aldrich). Then the specimens were serially dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol from 60% to 100% washes before embedded in paraffin wax. The 7 μm-thick sections were made and stained according to standard protocols for Hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E) (Sigma–Aldrich). All histological sections were analyzed with the image analysis system of ImageJ. All experiments were carried out 4 times, each on 1 or 2 mice; the value reported is the mean result for the 4 studies.

2.10. Histological and immunohistochemical analysis

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was used to detect luminal structures containing red blood cells. The von Kossa staining was used to visualize calcium deposits and mineralization properties. For immunohistochemistry, the sections were deparaffinized, and antigen retrieval carried out by heating the sections for 10 min at 93 °C in 10 mM Tris-base, 2 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 8.0. The sections were then blocked by incubation for 30 min at room temperature in blocking buffer (5% BSA in PBS) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with mouse anti-human CD31 antibodies (1:50 in blocking buffer; DakoCytomation, clone JC70A), mouse anti-human a-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) antibodies (1:200; Sigma–Aldrich, A2547 clone 1A4), mouse anti-human veimentin antibodies (1:200; abcam, V9), rabbit anti-osterix antibodies (1:200; abcam, ab22552,), or mouse/rabbit IgG (1:50 in blocking buffer; DakoCytomation). For mouse anti-human CD31 immuno-histochemistry, the sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated mouse secondary antibodies (1:200 in blocking buffer; Vector Laboratories), then bound antibody was detected using a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine detection kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, followed by hematoxylin counterstaining and Permount mounting. For mouse anti-human CD31 and mouse anti-human aSMA immunofluorescence studies, the sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with, respectively, Alexa Fluor 488- or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200; Invitrogen). All fluorescently stained sections were counterstained with DAPI (Invitrogen).

2.11. Microvessel density

Microvessels were quantified by evaluation of 10 randomly selected fields (400x magnification) of H&E-stained sections taken from the central part of the implant. Microvessels were identified as luminal structures containing red blood cells. Microvessel density was calculated by dividing the total number of red blood cell-containing microvessels by the area of each section and expressed as vessels/mm2. The percentage of human microvessels in the total microvessels and the luminal areas of the human microvessels were determined using ImageJ software after human-CD31 immunohistochemical staining. The values reported for each experimental condition are the mean ± the standard deviation for 3–5 individual mouse per condition.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Microcal Origin 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation). All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean. Comparison of values for different materials was carried out by one-way/two-way ANOVA. Significance levels were set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Collagen extraction from murine epidermal tissue facilitated by cell adhesion and proliferation

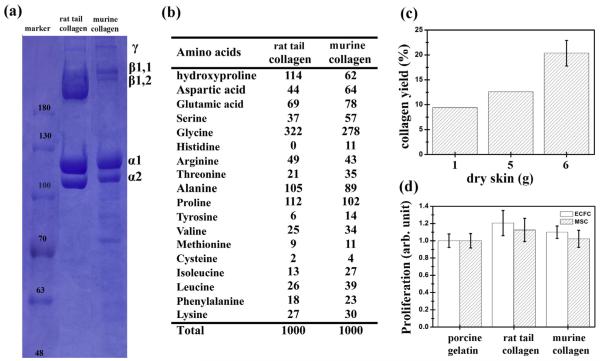

Protein patterns of collagen extracted from murine epidermis analyzed by the electrophoretic protein pattern (SDS) are shown in Fig. 1a. α1 and α2 chains of collagen with molecular weights of 117 and 108 kDa are similar to commercial collagen type I from rat tail. This result suggests that the majority of collagen extracted from murine epidermis tissue belongs to type I collagen. The a and β component band intensity of extracted collagen was lower than commercial collagen from rat tail and the purity was estimated to be around 40.45% by SDS patterns, while rat tail collagen served as control with 100% purity. The amino acid composition of collagen from rat tail and murine epidermis, expressed as residues per 1000 amino acid residues, is shown in Fig. 1b. Glycine constituted approximately one third of the total amino acid residues (278–332/1000 residues), which is a typical characteristic of different types of collagen. The presence of glycine at every third residue plays a major role in providing an inter-chain hydrogen bond perpendicular to the helical axis. Collagen from rat tail and murine epidermis was rich in proline, alanine, glutamic acid and hydroxyproline (hyp). The proline and hydroxyproline content of collagen derived from murine epidermis tissue was 164/1000 residues (16.4%). This is slightly lower than rat tail collagen (22.6%) and snapper skin collagen (18.7%). The content of hyp/protein of 0.115 mg/mg was measured and compared with commercial rat tail collagen (0.216 mg/mg) for hyp measurements. The low content of aromatic amino acids (tyrosine and phenylalanine) of 3.7% in collagen from murine epidermis tissue may contribute to a low level of antigenicity [40]. For evaluation of the procedure’s scalability, the yield of murine collagen extracted from 1, 5, and 6 g was around 9.4% (wt), 12.6% (wt) and 19.87 ± 1.99% (wt) of freeze-dried epidermal skin (Fig. 1c), respectively. Furthermore, the 19% (wt) yield was reached, which was almost the same amount as the collagen content in murine skin. Collagen is known to have the capacity to regulate cell behaviors such as adhesion, spreading, proliferation and migration, thus it has been extensively used to enhance cell–material interactions for both in vitro cell culture and in vivo tissue engineering applications [41]. To investigate the protein functionality of extracted murine collagen on cell proliferation, in vitro cell studies were carried out using human primary ECFCs and MSCs. Cell proliferation was assessed by the MTS assay, as shown in Figs. 1d and S2. After 2 days of culture, ECFCs and MSCs cultured on the surfaces coated with murine collagen and rat tail collagen (BD) showed almost the same proliferation capacity than those cultured on porcine gelatin (Sigma) coated plates. These results indicate that murine collagen extracted from epidermis has the same cell adhesion and proliferation capacity of human primary ECFCs and MSCs as rat-tail collagen control.

Fig. 1.

Characterizations of murine collagen extracted from murine dermis of skin. (a) SDS–PAGE patterns, (b) amino acid composition. (c) Yields of collagen extracted from 1, 5, and 6 g of dry murine skin. (d) Proliferation of ECFCs and MSCs grown on different coatings after 2 days of culture. Cells were cultured on a gelatin (Sigma)-, rat tail collagen (BD)- and murine collagen-coated polystyrene plates measured by MTS assay. Commercial rat tail type I collagen (BD) gels served as the control. The data are presented as average values ± standard deviation (n = 4).

3.2. Synthesis and characterization of collagen-Ph hydrogels

In order to conjugate more Ph groups to murine collagen, we measured the zeta potential of extracted murine collagen dissolved in HCl solutions and MES buffer as a function of pH. The zeta potential was 7.1–7.2 mV at pH 4 and then decreased to 0.18– 0.37 mV at pH 6, finally dropping from −0.2 to −0.5 mV at pH 8 in both HCl and MES solutions (Fig. 2c). Thus, the pHIEP (pH at which the zeta potential is zero) of extracted murine collagen was found to around 6.5 in HCl and MES buffer solution. From the 1H NMR spectra of murine collagen-Ph shown in Fig. 2e, the peaks at chemical shift (d) 6.6 ppm and 6.3 ppm, compared with unmodified murine collagen, indicated successful conjugation of tyramine with carboxyl groups in the amino acid residues to extracted murine collagen. With increasing pH values of MES buffers, the gelation time of collagen-Ph decreased from 75 s at pH 4 to 50 s at pH 6 and then increased to 275 to 300 s at pH 7 and pH 8 (Figs. 1d and S1b). Increasing conjugation reaction from 4 to 24 h was found to decrease the gelation time (Fig. S1c). The best condition for conjugating tyramine hydrochloride to murine collagen via the carbodiimide-mediated condenzation was shown in MES buffer with pH 6 at 4 °C for 24 h of reaction time, which resulted in the shortest gelation time and indicated a maximal immobilization of Ph groups (Figs. 1d and S1b-c). The total Ph content incorporated per gram of murine collagen under the preparation conditions was 4.9 × 10−2 g (murine collagen-Ph). Fig. 2f and g shows the dependence of gelation time on the concentrations of HRP and H2O2. Gelation time decreased from 560 ± 20 s to 220 ± 10 s with decreasing H2O2 concentration from 1250 μM to 19.5 μM at fixed HRP of 78 unit/μl. Furthermore, gelation time was tuneable from 265 ± 17 s to 71 ± 12 s with increasing HRP concentration from 78 units/μl to 1250 units/μl under a fixed concentration of H2O2 (156 μM). A significant result, which is promising for applications requiring in situ gelation, is that we could obtain murine collagen hydrogels within dozens of seconds, and in some cases within several minutes, by controlling the concentrations of HRP and H2O2. Increasing concentrations of H2O2 resulted in longer gelation times. From macroscopic images shown in Fig. 2h, there was no difference in the degree of opacity with increasing protein concentrations, H2O2 concentrations and synthesized pH values of MES after the formation of gels via HRP-catalysis. The yield of conjugation of tyramine to collagen was decreased slightly from 40% to 27% with a scale-up of the amount of dried murine collagen from 0.1 g to 0.6 g in a single immobilization process. The haemocom-patibility of extracted murine collagen and the synthesized murine collagen-Ph conjugates at concentrations of 1 mg/ml were also studied. As shown in Fig. 2j, murine collagen possessed less than 1% hemolysis, similar to the negative control (the normal PBS solution), while the positive control (distilled water) was set as 100% of hemolysis. After conjugating Ph groups to murine collagen, murine collagen-Ph still exhibited low hemolysis of 4.3 ± 2.0%.

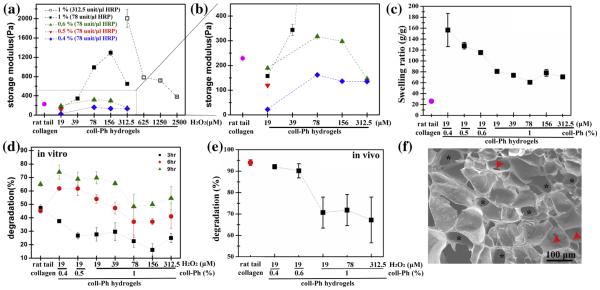

We used collagen-Ph hydrogels as our study model and the HRP concentration was optimized at 78 unit/μl as the gel point was within 5 min with increasing H2O2, which is very efficient for gel formation as an injectable system for clinical use. Fig. 3a and b summarizes the rheological properties of collagen-Ph hydrogels formed with varied collagen-Ph (0.4–1% (w/v)) and H2O2 (19–312 μM) concentrations at 78 unit/μl of HRP. Temperature/pH-sen sitivecross-linked rat tail collagen (BD) gels have less controllable in fabricating the desired structure with specific storage modulus, because the gels became 5 times more rigid as the pH of the collagen polymerization solution increased from 5 to 8 [42]. Here, BD gels serve as a control in having a storage modulus of 229 ± 12.9 Pa at pH 7.4. With increasing collagen-Ph concentration from 0.4% to 1%, the storage modulus (G′) increased from 22.1 ± 1.7 Pa to 189.3 ± 4.0 Pa at a fixed concentration of 19 μM of H2O2 and 78 unit/μl of HRP. The same trend where the storage modulus (G′) of 1% collagen-Ph hydrogels was significantly increased from 189.3 ± 4.0 Pa to 1293.4 ± 57.3 Pa, with an increase of H2O2 concentration from 78 to 156 unit/μl observed. The further increase in H2O2 concentrations to 312 μM resulted in a decline of G′ of 647.19 ± 18.13 Pa (Fig. 3a), which was potentially due to deactivation of the HRP with an excess amount of H2O2. In order to consume excess H2O2, we increased the HRP from 78 to 312 unit/μl, resulting in a higher storage modulus of 2005.5 ± 185.3 Pa. The G′ of murine collagen-Ph hydrogel could be tuneable, ranging from 22.1 ± 1.7 Pa to 2005.5 ± 185.3 Pa through various amounts of HRP, H2O2 and collagen-Ph conjugates. We also found that in contrast to the effect of H2O2 on hydrogel stiffness, a decrease in collagen-Ph concentration from 1% to 0.4% resulted in a significant decrease in hydrogel stiffness. The dependence of H2O2 concentration indicated that the more phenol moieties available in the system, the more H2O2 was needed to maximize the cross-linking density, namely with increasing gelation time. Thus, insufficient HRP would result in an incomplete enzyme-mediated reaction and a concomitant decrease in storage modulus and a slower gelation time (Fig. 3a). In our collagen-Ph system, excess H2O2 was observed at 312 μM of H2O2 under 78 unit/μl of HRP in 1% collagen-Ph hydrogels. The excess H2O2 not only deactivates HRP and decreases the stiffness of hydrogels, but also caused some toxicity to cells (Fig. S3). Whereas the storage moduli, biodegradation and swelling properties of collagen-Ph hydrogels changed sensitively with the cross-linking degrees, the approach taken in this study was to investigate how variation in cross-linking of collagen-Ph hydrogel influences vascular density and overall spatial organization of cells under angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. As a result of the higher crosslinking density in collagen-Ph hydrogels with higher concentration of H2O2 using a HRP concentration of 78 units/μl, the swelling ratio increased with a decrease in Ph content, i.e. lower concentration of collagen-Ph hydrogels, and with a decrease in the H2O2 concentration (Fig. 1g). Rat tail collagen gels had low swelling properties (25.98 ± 0.218) compared with the collagen-Ph hydrogels (60.8 ± 0.8–80.6 ± 1.64), regardless of the H2O2 concentration used, whereas the values for the decreasing concentration of collagen-Ph hydrogels ranged from 80.6 ± 1.64 to 156.5 ± 30.4. Collagen-Ph hydrogels also showed tuneable proteolytic degradability through precise control of H2O2 (19–312.5 μm) and content of collagen-Ph conjugates (0.4–1% (w/v)) at a fixed HRP of 78 unit/μl. Varying cross-linking degrees also resulted in concomitant changes in the degradation rates of collagen-Ph hydrogels both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 3d and e). No matter which cross-linked conditions were used, collagen-Ph hydrogels degraded slower than rat tail collagen (approximately 45%) after 3 h incubation with 0.2 unit/ml collagenase type I. After 6–9 h of incubation, 0.4–1% (w/v) collagen-Ph hydrogels cross-linked at a fixed HRP of 78 unit/μl and H2O2 of 19 μM, with the rate of degradation process faster than rat tail collagen gels (Fig. 3d). By further increasing H2O2 to 312.5 μM, the degradation increased in all test time points. Moreover, the same trend was also observed in the in vivo degradation profiles with increasing amounts of collagen-Ph or H2O2 slowing down the degradation rate of collagen-Ph hydrogels compared with the rat tail collagen gel (Fig. 3e). Furthermore, we observed relationships between storage moduli and biodegradation properties in different collagen-Ph hydrogels, e.g. higher storage moduli were measured and slower degradation properties were observed (Fig. 3a and d). The porosity and pore network structure of collagen-Ph hydrogels were investigated by SEM, revealing the microporous nature of the porosity (Fig. 3f, black asterisk) and high pore interconnection (Fig. 3f, red arrowhead). Taken together, we have successfully developed allogeneic murine collagen-Ph conjugates and the same techniques could be developed and utilized to have autologous biomaterials from a patients’ own skin to eliminate the possibility of a foreign body immune reaction or cross-species disease transmission. These collagen-Ph conjugates are easy to transport and can be stored at room temperature as a freeze-dried foam. To have collagen-Ph hydrogels with tuneable gelation time, mechanical properties and proteolytic degradability, collagen-Ph aqueous solutions were formed and gellable via a peroxidasecatalyzed enzyme reaction by simply mixing certain amounts of collagen-Ph conjugates, HRP and H2O2 in HCl solutions, which offers a broader range of stiffness extending to the application of an enzymatically cross-linked hydrogel system in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Fig. 3.

Tuneable mechanical, swelling and degradation properties of murine collagen-Ph (coll-Ph) hydrogels. (a and b) Modulation of rheological properties on murine collagen-Ph hydrogels with various amounts of murine collagen-Ph, H2O2 and HRP. (c) Swelling, (d) in vitro and (e) in vivo degradation profiles. Rat tail collagen gels (BD) were used as controls. (f) SEM analysis on the morphology of 1% (w/v) murine collagen-Ph hydrogels cross-linked at 78 unit/μl HRP and 156 μM H2O2 showed uniformed micro-sized pores (approximately 65 μM in diameter (black asterisk)) and interconnected pore structure (red arrows). The data are presented as average values ± standard deviation (n = 3–5). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

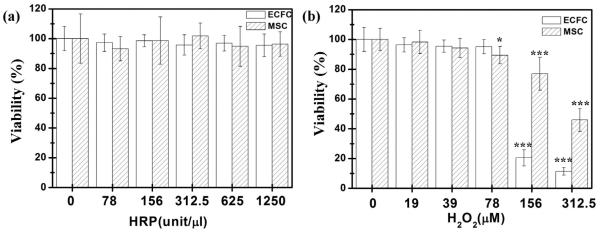

3.3. Biocompatibility of HRP and H2O2 on ECFCs and MSCs

We studied whether the presence of HRP and H2O2 could be causal parameters that directly affect cell viability and behavior. Thus, we added different concentrations of HRP and H2O2 directly into culture medium and evaluated the viability of ECFC and MSCs caused by these two chemicals after 2 days of incubation. We demonstrated that HRP and H2O2 were compatible with cell viability of both ECFCs and MSCs (viability >90%) throughout a wide range of HRP (0–1250 unit/ml) (Fig. 4a) and H2O2 (0–78 μM) (Fig. 4b); cell viability was only negatively affected beyond 156 μM of H2O2 exposure directly into medium. However, addition of HRP and H2O2 would react and combine immediately with collagen-Ph conjugates to form hydrogels, with residual and unreactive H2O2 decreasing, and which did not affect the viability capacity of ECFCs and MSCs in 2 days of culture. In further studies, we then selected a working range of H2O2 (19–78 μM) used to crosslink hydrogels and discussed the effects of collagen-Ph hydrogels on ECFC and MSCs.

Fig. 4.

Viability of ECFCs and MSCs cultured in the medium in addition with varied concentrations of (a) HRP (0–1250 unit/μl) or (b) H2O2 (0–312.5 μM). The data are the mean ± standard deviation for 3–5 independent experiments. *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001 compared with cells cultured in the medium without adding HRP or H2O2 (control).

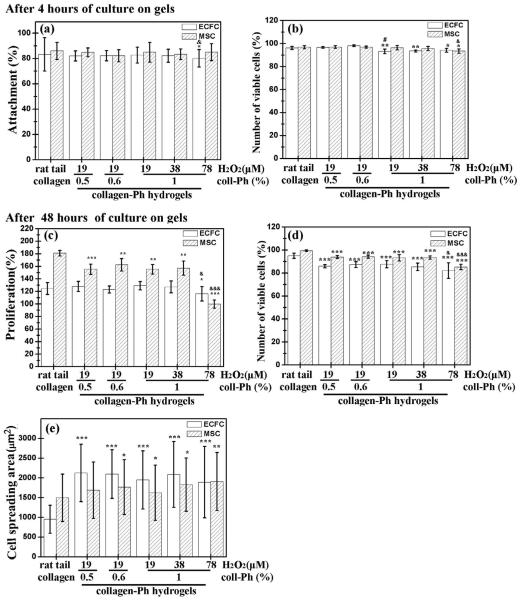

3.4. Cell behavior of ECFCs and MSCs grown on murine collagen-Ph hydrogels

We studied whether varying amounts of H2O2 and collagen-Ph could be used as parameters to modulate cell behavior grown on collagen-Ph hydrogels. To investigate the effect of collagen-Ph hydrogels on cell attachment and proliferation, in vitro studies were carried out using ECFCs and MSCs as models. Cell proliferation was assessed by the live/dead assay (Invitrogen), as shown in Figs. 5, S5 and S6. We sought to understand whether increasing the degree of polymerization of collagen-Ph hydrogels (Fig. 3) could compromise cellular behavior by altering concentrations of murine collagen-Ph and H2O2. First, concentrations of collagen-Ph in the range of 0.5–1% did not affect the capacity of ECFCs and MSCs to attach (>82%, Fig. 5a), proliferate (>123% for ECFCs and >155% for MSCs, Fig. 5c) and survive (>91%, Fig. 5b and d) compared with cells grown on rat tail collagen (BD) gels. Secondly, various amounts of H2O2 (19–78 μM) did not affect the capacity of ECFCs and MSCs to attach (>80% for ECFCs and >84% for MSCs, Fig. 5a) and survive (>92% for ECFCs and >93% for MSCs, Fig. 5b) compared with cells grown on rat tail collagen (BD) gels. However, the degree of cross-linking through adjustment of H2O2 concentration modulated cell proliferation and spreading on collagen-Ph hydrogels (Fig. 5c). For longer culture of 2 days, with increasing H2O2 from 19 to 78 μM, the MSC proliferation rate was maintained at 155.4 ± 7.7% and 157.0 ± 11.3% at H2O2 levels of 19 and 39 μM, respectively, and then decreased to 99.8 ± 6.6% at H2O2 of 78 μM (Fig. 5c). Additionally, we explored the spreading area of ECFC on collagen-Ph hydrogels at different cross-linked degrees at concentrations of H2O2 (19 μM: 1948.9 ± 737.6 μM2; 39 μM: 2088.2 ± 834.5 μM2; 78 μM: 1891.1 ± 904.9 μM2) were larger than ECFCs spread out on rat tail collagen gels (950.7 ± 354.3 μM2). However, MSCs retain almost the same spread size grown on collagen-Ph hydrogels (19 μM: 1623.2 ± 702.7 μM2; 39 μm: 1828.1 ± 675.1 μm2; 78 μm: 1908.6 ± 736.0 μm2) and rat tail collagen gels (1495.4 ± 600.3 μm2) (Fig. 5e). There was no statistically significant increase in cell spread and/or proliferation observed when the amounts of collagen-Ph conjugates and H2O2 concentration increased from 0.5% to 1% (w/v) at 19 μM of H2O2 and 19 to 39 μm at 1% (w/v) of collagen-Ph conjugates, respectively. However, a further increase of H2O2 concentrations to 78 μM at 1% (w/v) of collagen-Ph conjugates resulted in a significant decline of proliferation rate on ECFC and MSCs, which could be attributed to its high stiffness (G′ > 900 Pa). The results indicate that the amounts of H2O2 used in cross-linking collagen-Ph hydrogels significantly altered the cell proliferation behavior and largely improved the ECFCs and MSCs ability to spread. As reported previously, cell proliferation was often directly correlated to the stiffness of the substrate where cells resided and were grown in 2D culture [43–45].

Fig. 5.

Effects of the degree of cross-linking of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels on various functions of ECFCs and MSCs. (a) Attachment, (b) number of viable cells after 4 h of culture, (c) proliferation, (d) number of viable cells, and (e) spreading area after 48 h of culture of ECFCs (white bars) or MSCs (hatched bars) on 1% (w/v) murine collagen-Ph hydrogels with varying H2O2 concentrations (0–78 μM) at 78 unit/μl HRP and collagen concentrations. Rat tail collagen type I (BD) serve as controls. The data are the mean ± standard deviation for 3–5 independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared with the rat tail collagen type I (control). #p < 0.05 compared with the 0.5% (w/v) collagen-Ph hydrogels formed using 19 μM of H2O2 and 78 unit/μl of HRP. &p < 0.05 and &&&p < 0.001 compared with the 1% (w/v) collagen-Ph hydrogels formed using 19 μM of H2O2 and 78 unit/μl HRP.

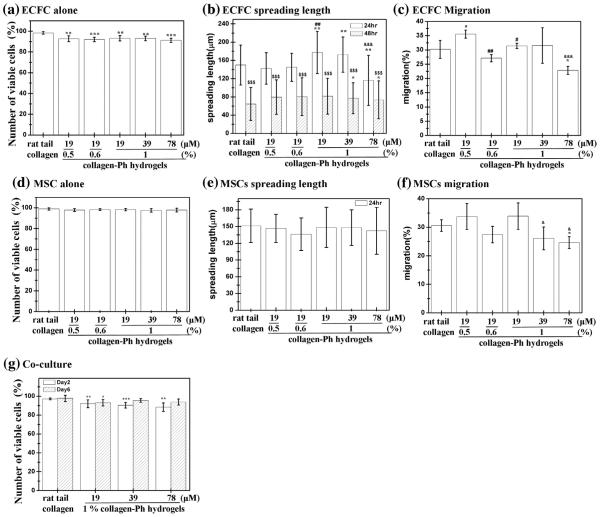

3.5. Monoculture of ECFCs or MSCs and co-culture of ECFCs and MSCs inside murine collagen-Ph hydrogels

Previous studies have shown that cross-linking degrees do compromise the cell viability and ability to spread, especially on primary stem cells [14,16,19,46,47]. To assess the effect of the degree of cross-linking of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels on 3D cell behavior, the 3D cell culture system was established and investigated in vitro. ECFCs and MSCs were encapsulated into collagen-Ph hydrogels independently and co-cultured in endothelial growth medium 2 supplemented with FBS (2%, Hyclone), SingleQuots containing human epidermal growth factor, human recombinant fibroblast growth factor-b, vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor, ascorbic acid, heparin, gentamicin/ amphotericin-B (Lonza), and 1x PS (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested into each hydrogel after 1 and 2 days of culture, and viability of encapsulated cells was evaluated using the live/dead kit to accurately distinguish the percentage of viable cells within each hydrogel (Fig. 6). For monoculture, the cell viability was above 92% for ECFCs and 97% for MSCs with increasing concentrations of collagen-Ph hydrogels from 0.5% to 1% at 19 μM of H2O2 and 78 unit/μl of HRP. Cell viability was above 89% for ECFCs and 97% for MSCs throughout various amounts of H2O2 (19–78 μm) at 78 unit/μl of HRP after 2 days in culture (Fig. 6a and d). Specifically, we found that increasing the concentration of H2O2 from 19 to 78 μm progressively diminished the capacity of both ECFCs and MSCs to spread inside collagen-Ph hydrogels (Fig. 6b and e) as well as the ability to migrate through collagen-Ph hydrogels (Fig. 6c and f). Qualitative images of intact hydrogels showed that the ECFCs spread well and underwent self-assembly to form interconnections, indicating an ability to form capillary network structures inside collagen-Ph hydrogels. Moreover, these resulting structures rapidly regressed after 2 days of culture and the same phenomena were observed in rat tail collagen gels and other published literature [3,41,48,49] (Figs. 6b and S7). On the other hand, MSCs were able to spread in all of the collagen-Ph hydrogels used, although the interconnected cellular network that formed was less extensive as the cross-linking degree increased (Figs. 6e and S8). These results were anticipated because higher concentrations of H2O2 increase the degree of polymerization on collagen-Ph hydrogels; in fact, provision of exogenous collagenase partially recovered the migratory capacity of the cells at higher H2O2 concentrations of 156 μm (data not shown), suggesting that cell spread and motility were likely inhibited as a result of too much collagen-Ph hydrogel cross-linking, resulting in stiffer and lower biodegradation. Next, we evaluated the ability of ECFCs and MSCs to proliferate, spread and organise when co-cultured (2:3 ECFC/MSC ratio) inside murine collagen-Ph hydrogels with different cross-linking degrees (Fig. 6g). Similar to monoculture, we found that both viability of ECFCs and MSCs slightly decreased with increased concentrations of H2O2 at any given time point (19 μM: 92.0 ± 4.2%; 39 μm: 90.4 ± 2.9%; 78 μm: 88.4 ± 4.5%; 156 μM), which was slightly lower than cells inside rat tail collagen gels (97.1 ± 1.0%) after 2 days of culture (Fig. 6g). After 6 days of co-culture, cell viability inside murine collagen-Ph hydrogels with various H2O2 increased to above 93% (19 μM: 93.1 ± 3.4%; 39 μM: 95.5 ± 1.9%; 78 μm: 93.9 ± 3.2%; 156 μM) but was still a little lower than cells inside rat tail collagen gels (97.8 ± 3.3%). In summary, the crosslinking degree modulated cell spreading and motility in collagen-Ph hydrogels compared with various concentrations of collagen-Ph conjugates. Moreover, we observed important differences between the monocultures and the co-cultures. The overall survival of ECFCs was increased by the presence of MSCs, although their survival was still compromized by higher cross-linking degrees.

Fig. 6.

Effects of the degree of cross-linking of murine collagen-Ph hydrogels on embedded monoculture of ECFCs or MSCs and co-culture with ECFCs and MSCs. (a) Number of viable cells (after 48 h); (b) cell spread length (after 24 and 48 h); (c) migration (after 48 h) of embedded ECFCs; (d) number of viable cells (after 48 h); (e) cell spread length (after 24 and 48 h); (f) migration of embedded (after 48 h) MSCs; (g) number of viable cells of co-culture with ECFCs and MSCs after 2 (white bars) and 6 (hatched bars) days of culture. The data are presented as average values ± standard deviation (n = 4–5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared with the rat tail collagen type I (control). &p < 0.05, &&p < 0.01 and &&&p < 0.001 compared with the 1% (w/v) collagen-Ph hydrogels formed using 19 μM of H2O2 and 78 unit/μl of HRP. #p < 0.05 and ###p < 0.001, compared to the 0.5% (w/v) collagen-Ph hydrogels formed using 19 μM of H2O2 and 78 unit/μl of HRP. $$$p < 0.001 compared with cells cultured for 24 h.

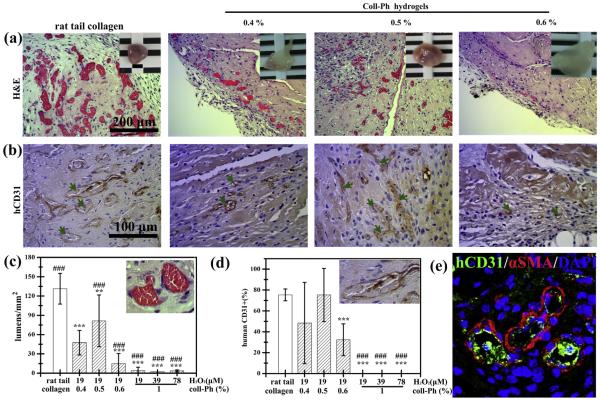

3.6. Anastomosis of engineered and host vasculatures

We therefore compared the extent of vascular network formation in murine collagen-Ph constructs to rat tail collagen type-I gels that commonly used in this field of research. Rat tail collagen type-I cell-laden constructs were formed by adding human ECFCs and MSCs to a solution of collagen type-I (3 mg/ml), then 250 μl (2 × 106 cells; 2:3 ECFC: MSC ratio) was injected subcutaneously into nude mice before gelation. As shown in Fig. 7, as expected from our previous results [7,18,30,32], rat tail type-I collagen were suitable for ECFC/MSC-mediated vascular network formation (131 ± 24 lumens/mm2). For the murine collagen-Ph cell-laden constructs, 250 μl of Ca/Mg-free DPBS containing 0.4–1% (w/v) collagen-Ph conjugates, 78 units/μl of HRP, 19–78 μM of H2O2, and human ECFCs and MSCs (2 × 106 cells; 2:3 ECFC: MSC ratio) was injected subcutaneously, then, after 7 days in vivo, the constructs were recovered and evaluated. H&E staining revealed that vascular network formation was affected by collagen-Ph concentration, as the number of lumens inside the construct increased with decreasing collagen-Ph concentrations (Fig. 7a–d). Quantitative evaluation of the explants revealed a significant increase in the total number of perfused blood vessels with a decrease in collagen-Ph concentrations from 1% (4 ± 5 lumens/mm2) to 0.5% (81 ± 40 lumens/mm2), followed by a decrease at lower collagen-Ph concentrations of 0.4% (47 ± 19 lumens/mm2) (Fig. 7c). The same trend of an increase in the percentage of the newly formed mature human microvessels, identified by staining for hCD31+/ aSMA+ (Fig. 7e), followed by a decrease with increasing collagen-Ph concentration (Fig. 7b and d), was seen within the collagen-Ph hydrogel. Moreover, we examined whether amounts of H2O2 (19, 39 and 78 μM) used to crosslink the 1% collagen-Ph gel modulated functional perfused vessel formation in vivo. H&E staining revealed few perfused blood vessels (<5 lumens/mm2, Fig. 7c and d), which were predominantly found as individual cells inside the construct, suggesting a lack of cell motility in 1% collagen-Ph hydrogels cross-linked using 78 units/μl of HRP and 19, 39 or 78 μM of H2O2. In order to demonstrate how biophysical/chemical investigations of collagen-Ph hydrogels influence the extent of the vascular network formation, perfused functional lumen density within implanted collagen-Ph constructs was then plotted against the corresponding physicochemical properties of collagen-Ph hydrogels (Table 1). Correlation was assessed using the slope of linear regression and the r2 (correlation coefficient) value. The lumen density is proportional to the in vivo biodegradation rate (r2 = 0.91⁄⁄) and swelling properties (r2 = 0.76⁄⁄), but inversely proportional to the storage modulus (r2 = −0.5⁄) of collagen-Ph hydrogels. The investigation revealed that the extent of the vascular network formation is highly dependent on in vivo biodegradation and swelling property of collagen-Ph hydrogels. Low degree of biodegradation and swelling of collagen-Ph hydrogels translates into constructs having lower microvessel density and smaller lumens; these observations are in line with recent reports [14,16,25,28] and our previous study [25] that correlate to ECM mechanical properties and capillary cell shape and function.

Fig. 7.

Enzymatic modulation of engineered vascular network in collagen-Ph constructs in vivo. Murine collagen-Ph conjugate mixtures with ECFCs and MSCs were subcutaneously injected into nude mice and enzymatically polymerized using 78 unit/μl of HRP and the indicated concentration of collagen-Ph and H2O2; the constructs were then removed and evaluated after 7 days in vivo. (a) Representative H&E-stained sections of constructs with different degrees of cross-linking of collagen-Ph hydrogels. The insets in the top panels show macroscopic views of the explants (scale bar 2 mm). (b) Human CD31+ECFCs identified by immunohistochemistry. The green arrows indicate areas with perfused lumens lined by hCD31+ECFCs. (c and d) The extent of human vascular network formation was quantified by counting luminal structures containing erythrocytes: (c) microvessel density and (d) percentage of the total blood vessels that are human CD31-expressing. (e) Representative confocal stained images of 0.5% collagen-Ph hydrogels using Alexa 488-conjugated-anti-CD31 antibodies (green) to label human ECFC-lined vessels and Alexa 594-conjugated anti-aSMA antibodies (red) to label perivascular cells. Nuclei were stained with 4′ ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The data are the mean ± standard deviation for 4–6 independent experiments. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.01 compared with rat tail collagen type I (control; BD). ###p < 0.01 compared with 0.4% collagen-Ph hydrogels formed using 19 μM of H2O2 and 78 unit/ μl of HRP. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Correlation between the physicochemical properties of collagen-Ph hydrogels and the formation of functional engineered ECFC-lined microvessels.

| Correlation coefficient (r2) | Lumen density | In vivo biodegradation | Swelling | Storage modulus (G′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumen density | 1.00 | |||

| In vivo biodegradation | 0.91** | 1.00 | ||

| Swelling | 0.76** | 0.87 | 1.00 | |

| Storage modulus (G′) | −0.50* | −0.62 | −0.74 | 1.00 |

Significance levels were set at

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

and *** p < 0.001.

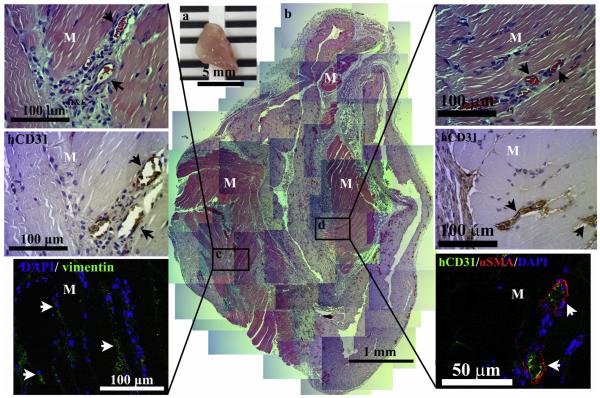

3.7. Engineered functional perfused vascular networks integrate with host skeleton muscle tissue

To determine whether the engineered vascular network was functional in supporting host tissues, cell-laden constructs were implanted intramuscularly into mouse anterior abdominal muscle defects to analyze the survival, integration and vascularization of the cell-laden implant in host. After 1 week of implantation, constructs were sectioned and immunostained using H&E staining, anti-human specific endothelial antibodies (hCD31) and h-vimentin antibodies (Fig. 8). In the H&E staining, lots of blood vessels and ingrowth of skeleton muscle cells were detected inside the implanted construct with very thin and barely detectable fibrous tissue around the implant (Fig. 8b). Mature human blood vessels (hCD31+) completely covered by aSMA-positive perivascular cells (Fig. 8c and d, arrows) containing intraluminal red blood cells were found inside MSC–ECFC implants, which originated mostly from donor cells, suggesting the rapid formation of functional anastomoses between the bioengineered human vascular network and the host vasculature. Additionally, these engineered human vascular networks were observed within elongated host skeleton muscle tissues to increase survival and support integration with host (Fig. 8c and d). These results suggest that engineering human vascular networks and their connection with host blood vessels inside collagen-Ph hydrogels can function and integrate with host tissues to provide sufficient nutrient and oxygen through timely and efficient vascularization in vivo.

Fig. 8.

Engineered vascular network supports the survival of host muscle tissue in vivo. 0.5% murine collagen-Ph conjugate mixtures with ECFCs and MSCs were injected into anesthetized mice by creation of a 2 mm × 2 mm defect in the anterior abdominal wall of the mice and enzymatically polymerized using 78 unit/μl of HRP and 19 μM of H2O2; the constructs were then removed and evaluated after 7 days in vivo. (n = 3) (a) The macroscopic view of the explants (scale bar, 5 mm). (b) Representative H&E-stained sections of constructs reveal vascularized host skeletal muscle tissue. Skeletal muscle area, M. (c) Images at higher magnification show human-CD31-expressing vessels carrying murine erythrocytes (arrows) and Alexa 488-conjugated-human-vimentin-expressing bmMSC-derived cells (green). (d) Representative confocal images of sections stained using Alexa 488-conjugated-anti-CD31 antibodies (green) to label human ECFC-lined vessels and Alexa 594-conjugated anti-aSMA antibodies (red) to label perivascular cells. The nuclei were stained by 4′ ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

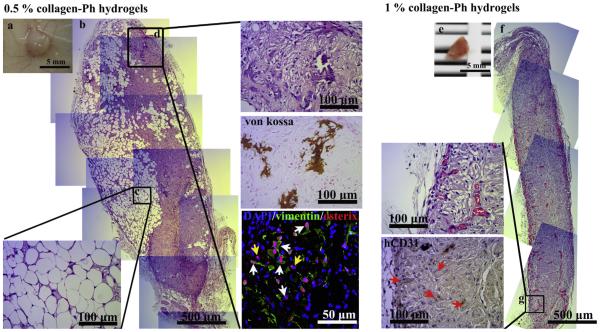

3.8. Tissue-engineered vascularized grafts in vivo

In order to examine the in vivo regenerative capacity of MSCs, we studied long-term co-transplantation of MSCs and ECFCs using an exogenous BMP-2-induced subcutaneous model to inject the cell-laden construct into nude mice. Rat tail type I collagen gel served as a control. At 1 month, the rat tail collagen implants were completely degraded and there was no sign of the collagen implants at the implantation site. Meanwhile, the 0.5% (Figs. 9a–d and S9a-b) and 1% (Fig. 9e–g and S9c-d) collagen-Ph cell-laden grafts were still present at the implantation site after 1 month in vivo. Histological examinations of explanted grafts showed extensive adipose tissue (730 ± 50 adipocytes/mm2; 42.35 ± 0.84% of area of a construct, Fig. 9c) and some mineralized nodule formation (0.84 ± 0.67% of area of a construct from von Kossa staining, Fig. 9d) inside 0.5% collagen-Ph grafts, whereas sparse vessel formation (approximately 28 lumens/mm2) was observed inside 1% collagen-Ph gels (Fig. 9e–g). The mineralized tissue (Fig. 9d) observed within 0.5% collagen-Ph hydrogels was derived from implanted cells rather than invading host cells confirmed by the h-vimentin staining. Of note, unlike other reports that used stiffer polymer scaffolds [50,51] (G′ rv kPa), the storage modulus (G′) of the 0.5% collagen-Ph hydrogel is only 119.3 ± 4.9 Pa, that is even softer than the rat tail collagen gel (G′ rv 229 ± 12.9 Pa). In the 0.5% collagen-Ph grafts, numerous osterix+ osteoblasts and mineralization distributed throughout the implant to form bone-like tissue (Fig. 9d). Most osteoblasts found inside implants originated from donor human MSCs (osterix+/h-vimentin+ cells), confirming that MSCs embedded under the influence of BMP-2 and collagen-Ph gels differentiated into mineralized osteoblasts to increase mineralized matrix deposition. On the other hand, inside 1% collagen-Ph constructs, only a few blood vessels (<5 lumens/mm2) containing erythrocytes were detected at day 7 (Fig. 7c and d). After 1 month, higher numbers of murine perfused blood vessels (hCD31-negative lumens (Fig. 9g); approximately 28 lumens/mm2) were uniformly distributed along the boundary of implants but there was still no sign of adipocytes and mineralized tissue inside 1% collagen-Ph constructs (Figs. 9e–g and S9c-d). These results indicate that the degree of polymerization of collagen-Ph hydrogel could be used to modulate not only the extent of hCD31+ECFC-lined vascular network formation, but also the regenerative capacity of MSCs in vivo. Taken together, cell growth and interim mechanical stability provided by collagen-Ph hydrogels not only improved short-term neovascularization of ECFC but also helped to improve the differentiation capacity of the transplanted MSCs for tissue regeneration and integration.

Fig. 9.

Enzymatic modulation of engineered vascularized tissue graft in cell-laden collagen-Ph hydrogels. 0.5% and 1% murine collagen-Ph conjugate mixtures with ECFCs and MSCs were subcutaneously injected into nude mice and enzymatically polymerized using 78 unit/μl of HRP and 19 μM of H2O2; cell-laden (a–d) 0.5% and (e–g) 1% collagen-Ph constructs were then removed and evaluated after 1 month of implantation (n = 3). (a) The macroscopic view of the 0.5% cell-laden collagen-Ph explant (scale bar, 5 mm). (b) The representative H&E-stained section of entire constructs contains (c) adipose tissue formation and (d) mineralized matrix. The calcium deposition and mineralization revealed by von Kossa staining. Human MSC-derived cells express h-vimentin (green). Osteoblasts express osterix (red). Whites: human osteoblasts osteoblasts (h-vimentin+/osterix+); yellow arrows: murine osteoblasts (h-vimentin-/osterix+). The nuclei were stained by 4′ ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (e) The macroscopic view of the 1% cell-laden collagen-Ph explant (scale bar, 5 mm). (f) The representative H&E-stained section of an entire construct. (g) Images at selected area in higher magnification show murine vessels (human-CD31-negavtive) carrying erythrocytes (arrows). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

To date, natural-based materials used extensively in the vascularization of tissue engineering constructs have several distinct advantages, such as biocompatibility to promote cell adhesion and cell growth, biodegradability to facilitate tissue remodeling and porous structure to allow vessel growth as well as nutrient and waste product transport [2,3]. Although the naturally derived matrices can provide abundant biological signals and degrade into physiologically tolerable compounds, they are still xenogeneic or allogeneic [52]. This may raise the risks of pathogen transmission and provocation of undesirable inflammatory and immunological reactions, leading to undesirable damage to the regenerated tissues and organs [4,52]. To avoid these risks, the use of autologous cells and scaffolds would eliminate negative host immune responses and lead to optimal tissue regeneration. The attainment of autologous cells from patients and the techniques to isolate, culture and expand autologous bone-marrow derived MSCs [53–55] and blood derived ECs [13,56] had been well established, but the availability of autologous scaffolds from donor tissues is highly limited. Collagen is a major component of the ECM (approximately 30% of total protein) and plays a vital role in the formation of tissues in animals [22]. Herein, we suggest that epidermal tissue can be an excellent source of autologous collagen and the extraction technique of type I collagen from murine epidermis has been successfully developed and well characterized in this study.

Currently, studies involving direct injection of stem/progenitor cells into tissues or circulation have shown limited success because of the short survival rate of transplanted cells, inefficient and inconsistent retention of transplanted cells following injection into tissues and lack of a suitable cellular microenvironment to modulate differentiation and timely new vessel formation [6,57–59]. One strategy to improve cell-based therapies is to design biomaterials with suitable biochemical and biophysical features as carriers that direct vessel formation in a predictable and reproducible means. Collagen scaffolds have also been shown to function as suitable carriers for EC-based strategies in vascular tissue engineering, respectively, but little is known regarding how specific properties of collagen gels correlate with endothelial-mediated vessel formation in vivo. Several in vitro studies have shown certain properties of collagen matrices, namely fibril density, stiffness and cell adhesive (RGDs)/degradable peptides (MMPs), can modulate EC/ECFC (CD31+)-mediated blood vessel densities and total vascular areas [18,19,27–29]. Moreover, collagen molecules self-assemble into fibrils with ordered structure is conducted in its physic-chemical properties, including pH, temperature, ionic strength, ion species and surfactants through the electrostatic interactions that occur during fibril and gel formation. By altering the pH value and gelation temperature, mechanical and chemical stability of collagen gels could be manipulated, but it is still difficult to precisely control the electrostatic interactions so far [42]. Thus, instead of using electrostatic interactions to form collagen gels, we fabricated collagen-Ph hydrogels formed from collagen-Ph conjugates by HRP-/H2O2-induced crosslinking via C–C or C–O bonds to form covalent bonds between the tyramine moieties added to the collagen. The mechanical properties, swelling behavior, and proteolytic degradability of collagen-Ph hydrogels were easily controlled as compared with collagen gels. In this study, we have shown that altering physicochemical properties of polymerized collagen-Ph hydrogels influence ECFC blood vessel formation in vivo using an established xenograft animal transplant model. More specifically, biodegradability, swelling and mechanical properties of collagen-Ph hydrogels, controlled by changing collagen concentration and cross-linking degrees, were found to affect ECFC and MSC remodeling as well as ECFC-lined vessel density, proportion of ECFC-lined to host vessels and human blood vascular areas. A notable finding was that decreasing cross-linking degrees and collagen-Ph concentration of collagen-Ph hydrogels showed an increase in overall vessel density and percentage of human-CD31-expressing blood vessels and total vascular area, suggesting the potential for increased blood perfusion. These findings demonstrate that matrix physicochemical properties directly impact ECFC-mediated vascularization, and therefore represent an important design criterion for cell-based delivery strategies.

The control of differentiation of stem cells into specific cell lineages is vital in regenerating specific tissues in the injured areas of the body. Sprouting of blood vessels has to occur in order to transport nutrients to transplanted cells, and the created tissue has to integrate with the host, leading to eventual heal damage [60]. Several groups showed that in the absence of biochemical signals, the physical cues from the matrix/scaffolds were enough to determine the differentiation phenotype for stem cells on 2D substrates in vitro [44,45,61], but the effect of stiffening 3D hydrogels is not so easy to discern [43,46,62]. In reality, the cells reside in a complex 3D environment that sends spatial, temporal and physicochemical signals to the cells to elicit specific responses in vivo. On the other hand, some studies have demonstrated that the presence of soluble induction growth factors could re-program the lineage specification in the initial stages of cell culture, leading to desired phenotypes but after several weeks in culture, the cells diverge into different lineage commitments by matrix elasticity [45,61]. These results raise the important question of whether biochemical stimulations can override physical cues to direct lineage specification of stem cell fate. In Zouani’s in vitro model [61], when the gels were covalently functionalized with osteogenesisinducing BMP-2 mimetic peptides, MSCs favoured differentiation to the osteogenic over myogenic lineage on soft gels, which were previously shown to induce myoblast formation in the absence of this biochemical ligand. These in vitro studies demonstrated that biochemical cues can modulate the way the cell senses the mechanical properties of this matrix to dominate the stem cell fate in a controlled environment outside of a living organism; however, in animal studies the biological environment in situ is more complicated. Although scaffold stiffness can guide and affect stem cell differentiation [60], it is still difficult to define a suitable scaffold that optimally stimulates a particular type of tissue regeneration in vivo, because biochemical cues within scaffolds are complex and varied with specific damaged tissues. Thus, the combined effect of the cooperation or co-regulation between the mechanical properties and the growth factors on the stem cell fate has not been well investigated. In a recent in vivo study [58], when MSCs were injected into the heart of mice after artificially inducing myocardial infarction, they showed calcified bone formation instead of the expected differentiation into heart muscle cells. This result was attributed to a stiff microenvironment created by scarred tissues at the damaged site, which no longer induced myogenic differentiation. As with our study, Lin et al. [12] used a BMP-2-induced subcutaneous animal model in which both ECFCs and MSCs were embedded as single cells in Matrigel to demonstrate that ECFCs can function as paracrine mediators to establish a perfused vascular network and improve the osteogenic regeneration from bone marrow derived MSCs in Matrigel [12]. However, Matrigel is derived from murine harboring Engelbreth–Holm Swarm (EHS) tumours, so immunological considerations limit its use for tissue engineering applications in clinic [63]. From our data, we demonstrated that the lack of support by the matrix impedes the onset of perfused blood vessels, which further affected the survival, long-term differentiation and regenerative capacity of trans-planted MSCs. Specifically, extensive adipose tissue formation and bone-like tissue were coexistence in our BMP-2 stimulated cell-laden constructs. Only few transplanted MSCs committed to osteogenic differentiation may be stimulated by soluble induction factors of BMP-2 in the early time period. These indicate that local physicochemical environments would affect the long-term differentiation behavior of transplanted stem cell in vivo, thereby increasing the viability and precisely controlled differentiation of locally transplanted MSCs that play important roles in engineering a particular tissue. Finally, the cell-laden collagen-Ph hydrogel shows very encouraging results in being able to engineer a vascularized tissue construct that brings very promising clinical applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Although we have initially engineered new vascularized tissue constructs by human blood-derived ECFC and bone marrow-derived MSCs with the support from suitable collagen-Ph gels at subcutaneous sites, more studies are needed to achieve the controlled differentiation of transplanted MSCs into the specific lineage to fabricate a desired vascularized tissue construct. Furthermore, in future studies, autologous progenitor or stem cells from immune-competent animals combined with autologous collagen-Ph gels may be considered for the development of applications in tissue regeneration.

5. Conclusion

Introducing cells or tissues grafts, native to the injured tissues, to promote the regenerative process is the ideal strategy in tissue engineering. Thus, somatic cell-based therapeutic studies can be considered an important tool in regenerative medicine. They rely on the successful delivery of living cells to the target location where they can produce a desired therapeutic effect by paracrine delivery of growth factors, cytokines and hormones to replace lost or damaged cells with donor cells that can integrate and regenerate into the damaged tissue. Despite the recent advances and promising results of cell-based therapies, substantial challenges remain in controlling the fate of transplanted cells. The success of these strategies might be significantly improved with the use of adequate cell carriers/scaffolds. Collagen-based matrices stand out as ideal materials for such applications. In this study, we reported a method for preparing autologous extracellular matrix scaffolds, murine collagen-Ph hydrogels, and demonstrated the suitability of injectable and enzymatically cross-linkable collagen-Ph hydrogels for use in supporting human progenitor cell-based formation of 3D vascular networks in vitro and in vivo. We also demonstrated that the biodegradability, swelling properties and stiffness of collagen-Ph hydrogels controlled by altering the degree of crosslinking could be used to tune not only the extent of vascular network but also adipose and mineralized tissue formation in vivo. This study emphasizes the importance of ECM in providing appropriate signals for endothelial-mediated vascular formation, which is critical for the earliest stages of organogenesis to engineer cell-based 3D tissue constructs. Moreover, this addresses some current clinical problems associated with cell-based therapies and may contribute to the design and optimization of clinically-compatible ECMs for ECFCs and MSCs. Based on these data, we propose the use of collagen-Ph hydrogels in regenerative engineering applications, including the engineering of 3D thick tissues and organs that require an adequate vascular supply to guarantee their survival and function.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

We reported a method for preparing autologous extracellular matrix scaffolds, murine collagen-Ph hydrogels, and demonstrated its suitability for use in supporting human progenitor cell-based formation of 3D vascular networks in vitro and in vivo. Results showed extensive human vascular networks can be generated within 7 days, engineered vascular density inside collagen-Ph constructs can be manipulated through refinable mechanical properties and proteolytic degradability, and these networks can form functional anastomoses with existing vasculature to further support the survival of host muscle tissues. Moreover, optimized conditions of cell-laden collagen-Ph hydrogel resulted in not only improving the long-term differentiation of transplanted MSCs into mineralized osteoblasts, but the collagen-Ph hydrogel also improved an increased of adipocytes within the vascularized bioengineered tissue in a mouse.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan Grant (NSC 102-2221-E-134-001 and MOST 103-2221-E-134-001 to Y.-C.C.) and a National Institutes of Health – United States Grant (R00EB009096, to J.M.M.-M.). The authors acknowledge the National Laboratory Animal Center, funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, for technical support in the histology-related experiments. The authors also thank the core facility of Multiphoton and Confocal Microscope System (MCMS) in College of Biological science and Technology, National Chiao-Tung University, Hsinchu, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2015.09. 002.

References

- [1].Jain RK, Au P, Tam J, Duda DG, Fukumura D. Engineering vascularized tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:821–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt0705-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Baiguera S, Ribatti D. Endothelialization approaches for viable engineered tissues. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tian L, George SC. Biomaterials to prevascularize engineered tissues. J. Cardiovasc Transl. Res. 2011;4:685–698. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shieh SJ, Vacanti JP. State-of-the-art tissue engineering: from tissue engineering to organ building. Surgery. 2005;137:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]