Abstract

Background

Genesis of persistent gastro-esophageal reflux symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy is not fully understood. We aimed at determining reflux patterns on 24-h pH-impedance monitoring performed on PPI and correlating impedance patterns and symptom occurrence in PPI non-responders.

Methods

78 PPI non-responder patients underwent 24-h pH-impedance monitoring on PPI. Reflux impedance characterization included gastric and supragastric belches and proximal extent of reflux. Symptoms were considered associated with reflux if occurring within 5 min after a reflux event. Patients were classified into 3 groups: persistent acid reflux (acid esophageal exposure (AET) >5% of time), reflux sensitivity (AET<5%, symptom index (SI) ≥50%), and functional symptoms (AET<5%, SI<50%). Dominant impedance pattern was determined for each patient.

Key results

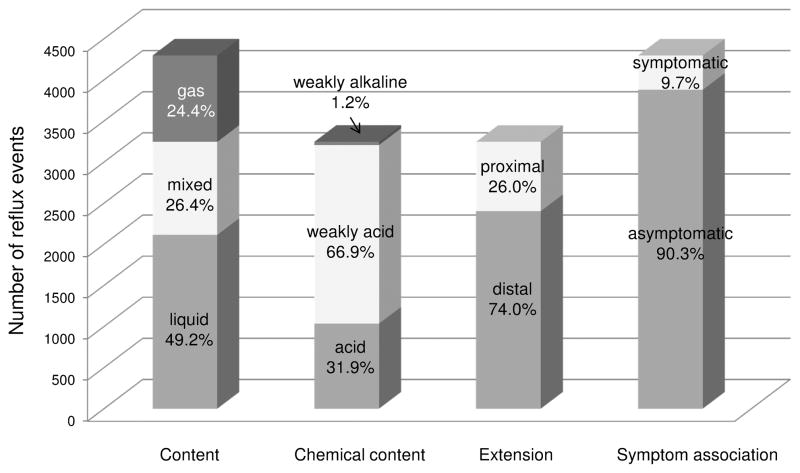

7 patients (9%) had persistent acid reflux, 28 (36%) reflux sensitivity and 43 (55%) functional symptoms. A total of 4,296 reflux events were identified (median per patient 45 (range 4–221)). Although liquid reflux was the most common pattern in all groups, patients with reflux sensitivity and functional symptoms had much more variability in their pattern profile with a large proportion being associated with gastric and supra-gastric belching. Only 417 reflux events (9.7%) were associated with symptoms. Reflux with a supragastric component and proximal extent were more likely to be associated with symptoms.

Conclusions & Inferences

The impedance reflux profile in PPI non-responders was heterogeneous and the majority of reflux events were not associated with symptoms. Thus, the treatment of PPI non-responders should focus on mechanisms beyond reflux, such as visceral hypersensitivity and hypervigilance.

Keywords: Gastro-esophageal reflux disease, pH-impedance monitoring, symptom, proton pump inhibitors

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms are frequently encountered in Western countries; they affect around 20% of the population. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the mainstay of GERD treatment and they add substantial cost to the health care system (1). While the success rate for healing esophagitis is very high (80 to 90%) (2), 20 to 60% of patients with GERD symptoms remain unsatisfied or symptomatic despite PPI therapy (3). Reasons for dissatisfaction and non-response are multiple: non-adherence to treatment, persistent esophageal acid exposure, reflux hypersensitivity or esophageal hypervigilance. Understanding the mechanisms of PPI non-response in GERD is of importance to develop and offer the best therapeutic options to patients. It may also help to decrease health cost by decreasing unnecessary PPI use.

Esophageal reflux monitoring is helpful in determining the association between reflux events and symptom occurrence. Combined pH-impedance monitoring detects reflux events based on the presence of liquid and gas into esophagus. These events are further characterized based on their pH as acid, weakly acidic or weakly alkaline (4). While reflux events are physiological and encountered in asymptomatic controls, they tend to be more frequent (5), more likely acidic (6) and more likely associated with symptoms (7) in patients who report GERD symptoms.

Investigators have attempted to determine reflux characteristics that might be associated with symptoms perception. In a series of 1,807 reflux episodes identified in 32 patients who underwent 24-h esophageal pH-impedance monitoring off PPI, only 203 (11.2%) were symptomatic (8). Compared to non-symptomatic episodes, symptomatic reflux episodes had lower nadir pH, higher proximal extent, longer volume and acid clearance time, and were preceded by greater esophageal cumulative acid exposure. In a similar study performed in 20 patients with typical GERD symptoms despite double-dose PPI therapy, 1,273 reflux episodes were identified and 312 (24.5%) were associated with symptoms (9). The only factor associated with perception was high proximal extent. Other studies suggested that reflux perception was enhanced by the presence of gas in the refluxate in patients with non-erosive reflux disease (10) and in patients with poor response to acid suppressive therapy (11). This is consistent with the observation of Bravi et al. that air swallowing might be an important factor in PPI non-response (12). Among patients with typical GERD symptoms and abnormal esophageal acid exposure off PPI, the frequency of air swallowing was greater in the 26 patients who failed to respond to PPI therapy compared to 18 patients who responded. Moreover, symptoms of PPI non-responders were more often preceded by mixed gas-liquid reflux events than those of PPI responders. Based on these observations, proximal extent of reflux and an air component may play a role in the persistence of GERD symptoms on PPI therapy.

Given the above data, we hypothesized that a more accurate description and categorization of reflux events may be helpful in explaining symptom correlation. We hypothesized that reflux patterns, including the direction of gas movement (belch versus supragastric belch), the timing between liquid and gas components (i.e. gas component preceding liquid component versus gas component within the liquid component) and proximal extent of the liquid component of the reflux might play roles in symptom genesis in patients who did not respond to PPI therapy. Hence, our goal was to describe detailed reflux patterns with ambulatory pH-impedance monitoring on PPI therapy and determine whether these patterns influence symptom generation in PPI non-responders.

Methods

Patients

We prospectively enrolled 78 consecutive PPI non-responder patients (28 males, mean age 51 years (range 19–76), mean body mass index (BMI) 29.3 kg/m2 (range 18.6–44.1)) who underwent 24-h pH-impedance monitoring on PPI from July 2011 to July 2014 at Northwestern University, Chicago, IL. PPI non-response was defined as persistent GERD symptoms despite PPI treatment and the requirement for further evaluation using ambulatory reflux testing. Patients presented with various symptoms of GERD: heartburn, regurgitations, chest pain, cough or sore throat. Patients with previous a history of scleroderma, esophagogastric surgery, or Barrett’s esophagus were excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board. All patients signed informed consent form.

Study protocol

High resolution manometry (HRM) (ManoScan, Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN) was performed prior to 24-h pH-impedance monitoring (Sandhill Scientific, Inc, Highlands Ranch, CO) to localize the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) and rule out major esophageal motility disorders. The pH-impedance catheter was positioned to measure esophageal pH 5 cm above the proximal border of the EGJ and impedance 3, 5, 7, 9, 15 and 17 cm above the proximal border of the EGJ. Study was performed on once-daily PPI in 25 patients and twice-daily in 53 patients. Patients were encouraged to maintain their daily activities, sleep schedule, and eat meals at their normal times. They were also instructed to press the event marker button on the pH-impedance data logger whenever they experienced a symptom suggestive of reflux.

Data analysis

Clinical data and high resolution manometry

Clinical data were obtained by searching patients’ medical records and baseline questionnaire profile. Esophageal HRM were analyzed using Manoview software (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN). EGJ end-expiratory pressure was measured in absence of swallowing and esophageal motility disorders were diagnosed using the Chicago Classification version 3.0 (13).

pH impedance study

pH-impedance recordings were analyzing using dedicated software (Bioview Analysis®, version 5.5.5.1, Sandhill Scientific Inc., Highlands Ranch, CO). Automated analysis was run first (Autoscan® function of Bioview Analysis® software) and tracings were then reviewed independently by 2 investigators (SR and HI). Disagreements were arbitrated by a 3rd investigator (JEP). Meals were excluded from the analysis.

Liquid reflux events were defined as a retrograde 50% drop in impedance starting distally at the level of the EGJ and propagating to at least the next 2 impedance channels. Only liquid reflux lasting more than 3 seconds were scored. Gas events were defined as a rapid (3,000 ohms/s) increase in impedance to >5,000 ohms, occurring simultaneously in at least 2 impedance channels. They were further subdivided into “gastric belch” when a rapid increase in impedance moved from distal to proximal channels and “supragastric belch” when a very rapid increase in impedance moved from proximal to distal followed by a retrograde decrease in impedance to baseline (14). Mixed liquid-gas events were defined as gas occurring immediately before or during a liquid reflux and were further subdivided into reflux starting with a gastric belch (when gastric belch preceded liquid component of the reflux), reflux induced by supragastric belch (when supragastric belch preceded liquid component of the reflux), reflux associated with gastric belch (when gastric belch occurred during the liquid component of the reflux), and reflux associated with supragastric belch (when supragastric belch occurred during the liquid component of the reflux). Liquid reflux events were considered swallow-induced if a swallow occurred immediately prior to the reflux event. Reflux events were considered to have reached the proximal esophagus when the liquid component of the reflux reached at least 15 cm above the EGJ. Thus, reflux events were classified as having one of 6 impedance patterns: gastric belch (no liquid reflux), supragastric belch (no liquid reflux), liquid reflux with gastric belch (either starting or associated with belch), liquid reflux with supragastric belch (either induced by or associated with supragastric belch), swallow-induced liquid reflux (no belching), and liquid reflux (no belching, no association with swallow). Liquid reflux with gastric or supragastric belch, swallow-induced liquid reflux and liquid reflux were further divided into proximal and distal events.

Nadir pH of each liquid and mixed reflux event was measured. Liquid and mixed reflux events were then classified as acidic when the pH dropped below 4, as weakly acidic when the nadir pH was between 4 and 7, and as weakly alkaline when nadir pH was above 7. Acid exposure time (AET) was calculated as total time at pH < 4 (including only pH drops associated with reflux events detected with impedance) divided by recording duration and expressed in percent.

Symptoms were considered associated with reflux events if occurring within 5 min after the reflux event (15). Symptom index (SI) was calculated as the number of symptoms associated with reflux events divided by the total number of symptoms and was expressed as percent.

Finally, patients were classified into 3 groups: persistent acid reflux (AET> 5% of time), reflux sensitive esophagus (AET<5%, symptom index (SI) ≥ 50%), and functional symptoms (AET<5% and SI<50%). As our purpose was to evaluate the direct relationship between reflux event and symptom, we used SI rather than Symptom Association Probability (SAP) to define the groups of PPI non-responders. Based on the most frequent impedance pattern observed in each patient, patients were also classified into 5 dominant impedance patterns: “gastric belch component” (if reflux events with gastric belch component were the most frequent events in the patient), “supragastric belch component” (if reflux events with supragastric belch component were the most frequent events), “swallow-induced reflux” (if swallow-induced reflux events were the most frequent events), “proximal reflux events” (if proximal reflux events were the most frequent events), and “liquid reflux” (if none of the above patterns was dominant).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as percentage or median (range) and compared using Chi-square or Mann Whitney tests. Dominant impedance pattern was determined for each patient and clinical and HRM characteristics of these dominant patterns were compared using Chi-square or Mann Whitney tests. Hierarchical linear models were used to estimate the probability of symptoms within a time interval of 5 minutes following reflux events. Models evaluated alternative contrasts of impedance patterns. In addition, the logistic relationship between nadir pH and symptom probabilities was estimated.

Results

Phenotypes of PPI non-responders

Among the 78 PPI non-responder patients included in this cohort, median acid exposure time was 0.5% (0.0–35.5) of total time and median number of reflux events (liquid, gas or mixed) per patient was 45 (4–221). Seven patients (9%) had persistent acid reflux, 28 (36%) reflux-sensitive esophagus and 43 (55%) functional symptoms. Characteristics of these groups are described in Table 1. While there was no difference in the detection of esophageal motility disorders among groups, reflux-sensitive patients had a more hypotensive EGJ than the others (8 mmHg (0–24) vs 11 (0–38), p=0.02). There was no difference between patients on PPI once daily and those on PPI twice daily; in particular distribution of persistent acid reflux, reflux sensitive esophagus and functional symptoms was similar.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics according to the group: persistent acid, sensitive esophagus, and functional symptoms. Data are expressed as median (range).

| Characteristics | Persistent acid reflux (n=7) | Sensitive esophagus (n=28) | Functional symptoms (n=43) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54 (29–58) | 48 (19–76) | 53 (26–75) |

| Sex (males) | 1 (14%) | 11 (39%) | 16 (37%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.3 (26.2–42.5)† | 27.8 (18.6–42.8) | 27.0 (18.8–44.1) |

| Esophagitis n (%) | 3/6 (50%)‡ | 3/19 (16%) | 4/32 (12.5%) |

| Acid exposure time (%) | 11.3 (5.5–35.5)* | 0.5 (0–4.2) | 0.3 (0–4.9) |

| Reflux events, n | 53 (4–84) | 55 (20–221)* | 41 (11–95)* |

| Number of symptoms reported per hour | 0.23 (0.00–5.95) | 0.28 (0.05–5.52) | 0.27 (0.00–7.70) |

| Symptom index | 52 (13–100) | 67 (50–100)* | 21 (0–43)* |

| Symptom index ≥50% | 3 (43%) | 28 (100%)* | 0* |

p<0.01 vs other groups;

p=0.06 vs other groups;

p=0.07 vs other groups

Characterization of impedance patterns

A total of 4,296 reflux events were identified. Reflux characteristics are presented in Figure 1. Impedance patterns were distributed as follow: gastric belch 17.2%, supragastric belch 7.3%, liquid with gastric belch 15.4% (starting and associated with gastric belch 13.5% and 1.9%, respectively), liquid reflux with supragastric belch 11.0% (induced by and associated with supragastric belch 8.6% and 2.4%, respectively), proximal liquid reflux 12.4%, swallow-induced liquid reflux 5.8%, and distal liquid reflux 30.9%.

Figure 1.

Characterization of the 4,296 reflux events detected. Reflux content, chemical content, extension and association with symptom are presented. Note that only reflux events with a liquid component (i.e. liquid and mixed reflux) were characterized with chemical content and proximal extension.

Regarding the occurrence of impedance patterns per patient, all patients exhibited liquid events. Gastric belches were encountered in 92% of patients, supragastric belches in 56%, reflux starting with gastric belch in 91%, reflux induced by supragastric belch in 61%, reflux associated with gastric belch in 55%, reflux associated with supragastric belch in 47%. Swallow-induced liquid or mixed reflux events were noticed in 83% patients, and proximal (liquid or mixed) reflux events in 88%. The occurrence of these different patterns was similar in patients with persistent acid reflux, reflux sensitive esophagus and functional symptoms. The only exception was that patients with functional symptoms exhibited less proximal reflux than the others (81% versus 97%, p = 0.03). Dominant patterns were similarly distributed in patients on PPI once and twice daily.

Distribution of dominant impedance patterns is presented in Table 2. Liquid reflux was the most frequent dominant pattern observed in our cohort. Patients with a dominant pattern of supragastric belching had lower BMI than patients with other dominant patterns (median BMI 23.6 (range 18.6–27.9) kg/m2 vs 28.8 (18.8–44.1) p<0.01). Ineffective esophageal motility was the most frequent motility disorder (41%) observed in patients with distal liquid reflux as a dominant pattern while HRM was most frequently normal in the other patterns (60%; p=0.04).

Table 2.

Dominant impedance patterns in the 3 groups of PPI non-responders

| Dominant impedance pattern | Persistent acid reflux (n=7) | Sensitive esophagus (n=28) | Functional symptoms (n=43) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric belch component | 1 (14%) | 7 (25%) | 13 (30%) |

| Gastric belch alone | 1 (14%) | 7 (25%) | 8 (19%) |

| Liquid reflux starting with gastric belch | 0 | 0 | 5 (12%)* |

| Supragastric belch component | 0 | 5 (18%) | 4 (9%) |

| Supragastric belch alone | 0 | 2 (7%) | 4 (9%) |

| Liquid reflux induced by supragastric belch | 0 | 3 (11%)* | 0 |

| Swallow-induced reflux | 0 | 1 (3.5%) | 0 |

| Proximal reflux | 0 | 1 (3.5%) | 3 (7%) |

| Liquid reflux | 6 (86%) ‡ | 14 (50%) | 23 (53%) |

p<0.05 vs other groups;

p=0.09 vs other groups

Reflux-symptom association

A total of 1,178 symptoms were reported with a median of 6 (0–159) symptoms reported per patient. Among the 4,296 reflux events identified, only 417 (9.7%) were associated with symptoms. The median number of symptoms per patient and per hour was 0.3 (0.0–7.7) and the median number of symptom associated with reflux event per hour was 0.1 (0.0–4.7). For the 66 patients who reported at least one symptom event, the symptom index was 42% (0–100). Patients with a dominant pattern of “supragastric belch component” had higher SI than the others (85 (13–100) vs 40 (0–100), p=0.02).

Based on hierarchical linear models analysis, the estimated probability that a reflux event was associated with symptom was 9.3% (95% confidence interval (CI) = 6.6–12.9). Proximal reflux events were more likely associated with symptoms than distal reflux events (12.7% (95% CI = 9.9–17.7) vs 7.8% (95% CI = 5.3–11.3), p=0.001). Reflux events with a supragastric belch component were more likely associated with symptoms than reflux with a gastric belch component (12.4% (95% CI = 7.8–19.2) vs 8.6% (95% CI = 6.2–12.0), p=0.017). Nadir pH was not significantly related to symptom probability (OR (95%CI) = 0.931 (0.839–1.034), p=0.18). Table 3 reports the results of a model taking into account belch component, proximal extent and swallow-induced events. Gastric belch alone, distal liquid reflux events alone, distal liquid reflux associated with gastric belch and swallow-induced distal reflux were less likely associated with symptoms than proximal liquid reflux associated with supragastric belch or swallow-induced proximal liquid reflux.

Table 3.

Impedance patterns and probability of association with symptoms

| Pattern | Number of patients with this pattern | Number of events | Mean number of events per patient | Probability of association with symptom (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric belch (without liquid reflux) | 72 | 738 | 10.3 | 7.5% (4.7–11.5) |

| Gastric belch with distal liquid reflux | 70 | 583 | 8.3 | 7.7% (5.0–11.5) |

| Gastric belch with proximal liquid reflux | 33 | 77 | 2.3 | 10.9% (5.4–20.9) |

| Supragastric belch (without liquid reflux) | 45 | 312 | 6.9 | 10.6% (6.4–16.9) |

| Supragastric belch with distal liquid reflux | 53 | 278 | 5.3 | 11.5% (6.8–18.6) |

| Supragastric belch with proximal liquid reflux | 23 | 194 | 8.4 | 17.1% (10.8–25.9)* |

| Swallow-induced distal liquid reflux | 58 | 212 | 3.7 | 8.8% (5.6–13.5) |

| Swallow-induced proximal reflux | 21 | 38 | 1.8 | 20.3% (10.4–35.8) ‡ |

| Distal liquid reflux (not swallow induced) | 77 | 1330 | 17.3 | 8.2% (5.6–11.7) |

| Proximal liquid reflux (not swallow induced) | 61 | 534 | 8.8 | 11.0% (7.3–11.1) |

p<0.05 vs gastric belch, gastric belch with reflux, distal liquid reflux, swallow-induced distal reflux and supragastric belch with distal liquid reflux

p<0.05 vs gastric belch, gastric belch with reflux, distal liquid reflux, swallow-induced distal reflux and proximal liquid reflux

Discussion

The major finding of this study was that PPI non-responder patients have a heterogeneous profile on pH-impedance monitoring. Although liquid reflux events were the most frequent patterns in all three PPI non-responders subtypes (persistent acid reflux, sensitive esophagus and functional symptoms), patients with sensitive esophagus and functional symptoms had much more variability in their impedance profile with a large proportion being associated with both sub- and supragastric belching. Furthermore, less than 10% of reflux events were associated with symptoms and the majority of symptoms recorded were not associated with reflux. Even if some reflux patterns tended to be more likely associated with symptoms, the association remained weak.

Our initial hypothesis that different impedance patterns might explain symptoms in PPI non-responders was not confirmed by these data. Rather we observed heterogeneity in the impedance profiles and no profile that was clearly associated with subtypes of PPI non-responders. This finding might question the role of pH-impedance monitoring in PPI non-responders. Previous studies have also searched for predictive factors of response to PPI therapy based on pH-impedance criteria. In a series of 100 patients who underwent pH impedance monitoring off PPI, Zerbib et al. failed to find any reflux characteristics that might predict response to PPI therapy (16). Patel et al. demonstrated that impedance profile did not predict response to PPI, but acid exposure time off PPI did predict response (17). Hence, the classical impedance parameters that include gas and liquid content and proximal extent have not been shown to be useful in predicting PPI response.

Our choice of using esophageal acid exposure rather than total number of reflux events is directly based on the study of Patel et al. (17) as esophageal acid exposure was the only factor able to predict PPI response. Further we decided to consider the threshold of 5% for pathological esophageal acid exposure as the aim of PPI treatment is to relieve symptoms and also to “normalize” esophageal acid exposure. We felt that using threshold established in healthy controls on PPI was somewhat artificial to define disease state.

In our study we chose using a 5-minute time frame to evaluate the association between reflux and symptom instead of the common 2-minute time frame. We acknowledge that 2-minute time frame is the optimal time to diagnose symptom-reflux association (18) and using a longer time frame is a limitation of our study. Our purpose was to assess symptom mechanisms and thus we decided to increase the sensitivity of this association by increasing the time frame to 5 minutes. Despite this longer time frame, a low proportion of reflux events were associated with symptoms in our series. This was previously noted by Tutuian et al. in a series of 120 patients who underwent pH-impedance monitoring on PPI using a 5-minute frame for reflux-symptom association as us (11). They observed that mixed reflux and reflux with proximal extent were more likely associated with symptoms. Our results are in line with those findings and provide a more detailed description of the type of gas-reflux pattern. The reflux events that were most likely symptomatic reached not only the proximal esophagus but were also associated with a supragastric component or were swallow-induced. The role of supragastric belches in the genesis of symptoms was reported in 90 patients who underwent 24-h impedance monitoring off PPI as part of the work-up for reflux symptoms (19). We demonstrated that this mechanism was also preponderant in PPI non-responders. Supragastric events and swallow-induced events share a common feature: both of them start with a swallow component. Thus, these events may or may not be induced voluntarily. They may also be secondary to sensitization or hypervigilance and are aimed at relieving some digestive tract discomfort.

Our results may have important clinical implications as the current paradigm is to treat all reflux events the same. Acidity is the primary target and PPIs are very effective in controlling acid exposure as evident by the low number of patients with abnormal acid exposure on PPI therapy. When PPIs fail to relieve symptoms, it has been proposed to target the number of reflux events as this should decrease reflux burden. However, our results suggest that there are major problems with this approach and that this could potentially explain why the improvement in symptom control with reflux inhibitors has been poor. For example, lesogaberan, a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-B receptor agonist which reduces the frequency of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations, resulted in symptom relief in 16% of patients who did not respond to PPI therapy versus 8% for placebo (p=0.03) when used as PPI add-on therapy (20). Arbaclofen placarbil, a pro-drug of the GABA-B agonist baclofen, was not superior to placebo as add-on therapy in PPI non-responders (21). Due to the minimal (if any) efficacy of these drugs, most companies have abandoned their development. The heterogeneity we observed in our cohort of PPI non-responders may help explain the failure of these medications. None of the reflux inhibitors targeted a specific type of reflux and it is unlikely that any of these agents would preferentially reduce supragastric events or reduce proximal extent. On a purely numerical level, it is unlikely that reducing reflux event numbers would substantially reduce symptoms when only a small portion of reflux events are associated with symptoms. This approach would appear to be futile in PPI non-responders and treatment approaches should shift toward improving symptoms, as opposed to reducing reflux as there is little direct evidence to support a reflux-symptom correlation.

Our study has limitations. All patients were enrolled from a single center and sample size for each impedance pattern was limited. However, compared to previous studies, we included a substantial higher number of PPI non-responder patients. For example Bredenoord et al. (8) and Zerbib et al. (9) who examined the correlation between reflux patterns and symptoms occurrence reported on 32 and 20 patients respectively. Another limitation of the current study was the fact that we did not evaluate baseline impedance in our series as some data suggests this may help predict PPI response in patients with GERD symptoms. De Bortoli et al. showed that PPI response was associated with lower impedance baseline in patients with functional heartburn (negative endoscopy, negative acid exposure time, negative SI) (22). Instead of searching for predictive factors of PPI response, we chose to focus on patients identified as PPI non-responders and search for specific impedance patterns associated with symptoms.

In conclusion, PPI non-responders have a heterogeneous reflux profile as determined by multichannel intraluminal impedance monitoring. Most reflux events are not associated with symptoms and the type of reflux pattern was not predictive of symptom perception. This suggests that the target of treatment in PPI non-responders should be shifted to focus on altering sensitivity and reducing hypervigilance. Speech therapy might be also an option in patients with reflux with supra-gastric component. Escalation of anti-reflux therapy in this patient group should be approached cautiously as a reduction in reflux number may not be the appropriate therapeutic endpoint for patients not responding to PPI.

Key messages.

The heterogeneity of PPI non-responders profiles might explain the failure of reflux inhibitors and the treatment of these patients should be focused on mechanism beyond reflux.

The goal of our study was to determine reflux patterns on 24-h pH-impedance monitoring performed on PPI and to correlate impedance patterns and symptom occurrence in PPI non-responders.

Reflux impedance patterns were characterized on 24-h pH-impedance monitoring performed on PPI in 78 PPI non-responder patients. Association between reflux impedance patterns and symptom occurrence was studied.

The impedance reflux profile in PPI non-responders was heterogeneous and the majority of reflux events were not associated with symptoms

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by R01 DK092217 (JEP-LK) from the United States’ National Institutes of Health—Digestive Diseases and Kidney (NIDDK).

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: John E Pandolfino, MD.

Specific author contributions: SR, LK and JEP wrote the paper; JEP and LK designed the study; PK, KE, LF and BM collected the data; SR, IH and JEP analyzed the data; ZM performed the statistical analysis; all the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Potential competing interests: Sabine Roman serves as a paid consultant for Given Imaging/Covidien/Medtronic. John E. Pandolfino serves as a paid consultant for AstraZeneca.

References

- 1.Everhart JE, Ruhl CE. Burden of digestive diseases in the United States part I: overall and upper gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:376–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards SJ, Lind T, Lundell L, Das R. Systematic review: standard- and double-dose proton pump inhibitors for the healing of severe erosive oesophagitis -- a mixed treatment comparison of randomized controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:547–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag H, Becher A, Jones R. Systematic review: persistent reflux symptoms on proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care and community studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:720–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sifrim D, Castell D, Dent J, Kahrilas PJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux monitoring: review and consensus report on detection and definitions of acid, non-acid, and gas reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1024–31. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Tutuian R, et al. The role of nonacid reflux in NERD: lessons learned from impedance-pH monitoring in 150 patients off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2685–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sifrim D, Holloway R, Silny J, et al. Acid, nonacid, and gas reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease during ambulatory 24-hour pH-impedance recordings. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1588–98. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bredenoord AJ. Mechanisms of reflux perception in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:8–15. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Curvers WL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Determinants of perception of heartburn and regurgitation. Gut. 2006;55:313–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zerbib F, Duriez A, Roman S, Capdepont M, Mion F. Determinants of gastro-oesophageal reflux perception in patients with persistent symptoms despite proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2008;57:156–60. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.133470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerenziani S, Sifrim D, Habib FI, et al. Presence of gas in the refluxate enhances reflux perception in non-erosive patients with physiological acid exposure of the oesophagus. Gut. 2008;57:443–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.130104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tutuian R, Vela MF, Hill EG, Mainie I, Agrawal A, Castell DO. Characteristics of symptomatic reflux episodes on Acid suppressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1090–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bravi I, Woodland P, Gill RS, Al-Zinaty M, Bredenoord AJ, Sifrim D. Increased prandial air swallowing and postprandial gas-liquid reflux among patients refractory to proton pump inhibitor therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:784–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160–74. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Sifrim D, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Aerophagia, gastric, and supragastric belching: a study using intraluminal electrical impedance monitoring. Gut. 2004;53:1561–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiener GJ, Richter JE, Copper JB, Wu WC, Castell DO. The symptom index: a clinically important parameter of ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:358–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zerbib F, Belhocine K, Simon M, et al. Clinical, but not oesophageal pH-impedance, profiles predict response to proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 2012;61:501–6. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A, Sayuk GS, Gyawali CP. Acid-based parameters on pH-impedance testing predict symptom improvement with medical management better than impedance parameters. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:836–44. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam HG, Breumelhof R, Roelofs JM, Van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. What is the optimal time window in symptom analysis of 24-hour esophageal pressure and pH data? Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:402–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02090215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kessing BF, Bredenoord AJ, Velosa M, Smout AJ. Supragastric belches are the main determinants of troublesome belching symptoms in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1073–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boeckxstaens GE, Beaumont H, Hatlebakk JG, et al. A novel reflux inhibitor lesogaberan (AZD3355) as add-on treatment in patients with GORD with persistent reflux symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor therapy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60:1182–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.235630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vakil NB, Huff FJ, Cundy KC. Randomised clinical trial: arbaclofen placarbil in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--insights into study design for transient lower sphincter relaxation inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:107–17. doi: 10.1111/apt.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Bortoli N, Martinucci I, Savarino E, et al. Association Between Baseline Impedance Values and Response Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients with Heartburn. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]