Summary

Brown adipocytes (BAs) play important roles in body temperature regulation, energy balance, and carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Activities of BAs are remarkably diminished in obese and diabetic patients, providing possibilities of transplanting functional BAs resulting in therapeutic benefit. Here, we show generation of functional BAs by cellular reprogramming procedures. Transduction of the PRDM16 gene into iPSC-derived embryoid bodies induced BA phenotypes (iBAs). Moreover, normal human fibroblasts were directly converted into BAs (dBAs) by C/EBP-β and C-MYC gene transduction. Approximately 90% of the fibroblasts were successfully converted within 12 days. The dBAs were highly active in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism. Mouse dBAs were induced by Prdm16, C/ebp-β, and L-myc genes, and after transplantation, they significantly reduced diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in an UCP1-dependent manner. Thus, highly functional BAs can be generated by cellular reprogramming, suggesting a promising tailor-made cell therapy against metabolic disorders including type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Highlights

-

•

Transduction of PRDM16 into iPSC-derived embryoid body cells induces BA phenotypes

-

•

Human fibroblasts are directly converted into BAs by C/EBP-β and c-Myc transduction

-

•

The efficiency of direct conversion is approximately 90%

-

•

Reprogrammed BAs are metabolically active and reduce obesity and type 2 diabetes

iPSC-derived embryoid body cells were induced into brown adipocytes (iBAs) by PRDM16 gene transduction. Human fibroblasts were directly converted into BAs (dBAs) by C/EBP-β and c-Myc gene transduction with an efficiency of 90%. The dBAs exhibited high metabolic activity. Mouse dBAs were induced by PRDM16, C/EBP-β, and L-Myc genes and significantly reduced insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in an UCP1-dependent manner.

Introduction

Brown adipocytes (BAs) have unique roles in energy expenditure and non-shivering thermogenesis, which is contrary to white adipocytes (WAs) that store excess energy obtained from food in the form of lipids (Gesta et al., 2007, Chechi et al., 2013). The BAs specifically express uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) at the mitochondrial inner membrane to dissipate the electrochemical proton gradient as heat, playing a pivotal role in regulation of body temperature, energy balance, and adiposity. In rodents, BAs prevent diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance, and type II diabetes (Kontani et al., 2005). Until recently, however, the significance of BAs in human remained controversial, because BAs are rarely detectable in the adult human. Since 2009, positron emission tomography (PET) using 18F-fluorodeoxyglocose (FDG) has clearly visualized metabolically active brown adipose tissue (BAT) in supraclavicular, mediastinal, paravertebral, and perirenal regions characterized by robust uptake of 18F-FDG upon acute cold exposure (Saito et al., 2009, van Marken Lichtenbelt et al., 2009, Cypess et al., 2009). Interestingly, the BA activity considerably varies from person to person and correlates inversely with age, fasting plasma glucose levels, and BMI (Saito et al., 2009, Ouellet et al., 2011, Ouellet et al., 2012). These findings strongly suggest the importance of BAs in physiological regulation of the whole-body energy balance and body fat accumulation, as well as the pathophysiology of obesity and metabolic diseases in humans. If human BAs with high energy expenditure activity can be artificially generated, the technology may greatly facilitate basic as well as applied research of these BAs. Especially, transplantation of such BAs may provide a regenerative therapy to control metabolic diseases, including diabetes mellitus.

Yamanaka’s group demonstrated that mammalian somatic cells can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) with embryonic-stem-cell-like characteristics by transducing genes for transcription factors, Octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4 (OCT4), SOX2, KLF-4, and C-MYC (so called reprogramming factors; Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006, Takahashi et al., 2007), strongly suggesting that a small number of key transcription factors may globally change epigenetic programming in somatic cells to convert their fates (Meissner, 2010, Papp and Plath, 2011). More recently, somatic cells were redirected into another differentiated cell lineage, without passing an intermediate pluripotent stage, by transducing a set of transcription factors that play crucial regulatory roles in the differentiation of the destination cell; direct conversion, or direct reprogramming, of murine fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes (Ieda et al., 2010, Inagawa et al., 2012, Inagawa and Ieda, 2013), neurons (Kim et al., 2011, Kim et al., 2012, Caiazzo et al., 2011, Han et al., 2012), chondrocytes (Hiramatsu et al., 2011), and hepatocytes (Sekiya and Suzuki, 2011, Huang et al., 2011), as well as of human fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes (Wada et al., 2013, Nam et al., 2013), neurons (Pang et al., 2011, Caiazzo et al., 2011, Kim et al., 2012), and hematopoietic cells (Szabo et al., 2010) have been reported. Although the efficiencies of direct conversion were generally low (0.005%–30% of fibroblasts were successfully converted into the cells of interest; Thier et al., 2012, Sekiya and Suzuki, 2011, Pang et al., 2011, Nam et al., 2013, Kim et al., 2011, Kim et al., 2012, Inagawa et al., 2012, Inagawa and Ieda, 2013, Ieda et al., 2010, Huang et al., 2011, Han et al., 2012, Caiazzo et al., 2011), these technologies may be quite valuable for generation of the desired cells that could be used in basic research as well as in regenerative therapy for various human disorders. We have recently succeeded in directly reprogramming human fibroblasts into osteoblasts that massively produced bone matrix and contributed to bone regeneration with an efficiency as high as 80% (Yamamoto et al., 2015).

In the current study, we directed our efforts to generate BAs from iPSCs and fibroblasts by introducing the genes that play central roles in BA development as well as in somatic cell reprogramming and analyzed their functions in culture and transplanted animals.

Results

iBAs Induced from iPSCs Suppressed Obesity and Diabetes

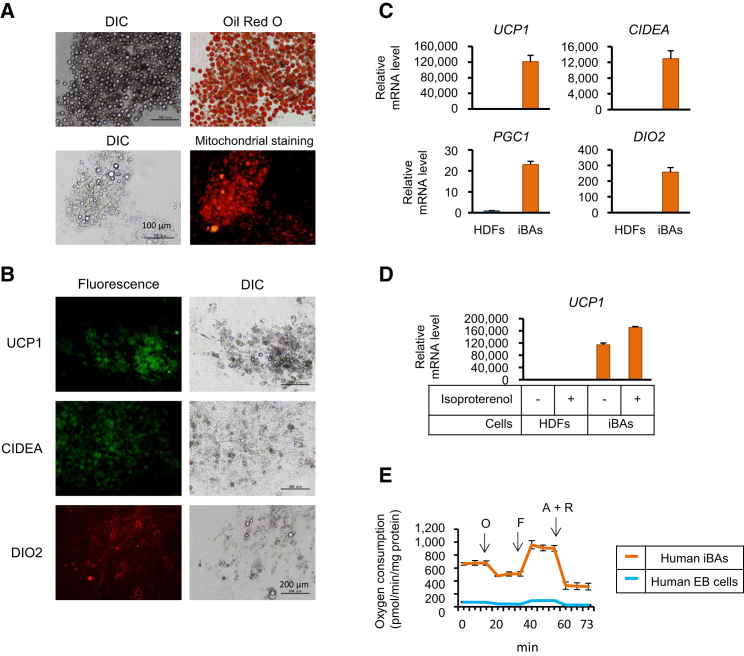

Human iPSCs were cultured with retinoic acid (RA) at doses of 25 μM (initial 7 days) and 50 μM (next 10 days), followed by transduction of the gene encoding the PRDM16 (PRD1-BF1-RIZ1 homologous domain containing 16) that was reported as the key regulator of BA differentiation (Seale et al., 2007, Seale et al., 2008). After culturing for another 12 days, approximately 75% of the cells showed BA-like appearance characterized by multilocular lipid droplets and abundant mitochondria (Figure 1A). The cells highly expressed UCP1, CIDEA, and DIO2 genes that are known to be specifically expressed in BAs (Figures 1B and 1C). Stimulation of these cells (namely iBAs) with isoproterenol, a general agonist of β-adrenergic receptors, resulted in further elevation of expression level of UCP1 mRNA, which is a typical adrenergic response of BAs (Figure 1D). The human iBAs showed remarkably high rates of oxygen consumption and uncoupling respiration (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Human iBAs Induced from iPSCs

(A and B) Human iPSCs were cultured in the presence of RA followed by transduction with PRDM16 retroviral vector. After culturing for 12 days, cells were subjected to Oil Red O and mitochondrial staining (A), as well as immunostaining with the indicated antibodies (B). Original magnification was 100×.

(C) Real-time RT-PCR was performed to evaluate mRNA levels of the indicated genes in HDFs and hiBAs.

(D) Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) and human iBAs were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of isoproterenol. Twelve hours later, UCP1 mRNA levels were evaluated by real-time RT-PCR.

(E) Oxygen consumption of the indicated cells was evaluated. Oligomycin (O), FCCP (F), and antimycin A and rotenone (A + R) were serially added to the culture at the indicated time periods.

In (A)–(E), n = 3 cultures per group. In (C) and (D), values (average ± SD) were normalized to β-ACTIN mRNA and expressed relative to values for the HDFs (set to 1.0; n = 3 cultures per group). In (E), values are average ± SD (n = 3 cultures per group). The experiments were repeated more than three times.

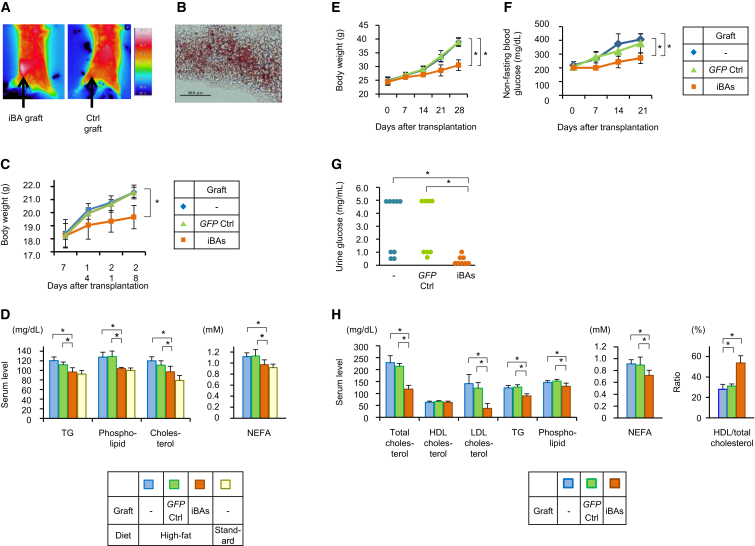

We obtained mouse iBAs as above and assessed their metabolic activities in vitro and in vivo. The mouse iBAs expressed Ucp1 and Cidea mRNA at comparable levels to those in the BAT (Figure S1A). They were rich in lipid deposits and mitochondria (Figure S1B) and showed a high rate of uncoupling respiration (Figure S1C). The iBAs were subcutaneously transplanted into syngenic mice, and their heat-producing activity was measured. As shown in Figure 2A, cold exposure resulted in heat production at site of the graft. Histological examinations revealed the presence of Oil Red O-positive iBAs in the graft (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

iBAs Suppressed Diet-Induced Obesity and Diabetes in Mice

(A and B) C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously transplanted with syngenic iBAs or control cells that had not been transduced with Prdm16 (d0). Two weeks after the transfection, thermographic images of mice were captured after exposure to 4°C for 2 hr (A). Mice were then sacrificed, and graft tissue sections were stained with Oil Red O (B; original magnification was 40×).

(C and D) C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously transplanted with syngenic iBAs or GFP-transduced cells as control and housed on either standard- or high-calorie diet. Body weights of mice were measured (C), and serum lipid concentrations were determined 4 weeks after transplantation (D).

(E–H) KK-Ay diabetic mice were subcutaneously transplanted with syngenic iBAs or GFP-transduced fibroblasts as a control. Body weights (E) and non-fasting serum glucose levels (F) of the mice are shown. Urine glucose levels were measured 3 weeks after the transplantation (G), and serum lipid concentrations were determined 4 weeks after the transplantation (H).

In (C)–(H), values are average ± SD (n = 8 mice per group) for one out of two independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05 (two-sided Student’s t test). In (A) and (B), n = 3 mice per group. The experiments were repeated more than twice. See also Figures S1 and S2.

The mice transplanted with iBAs were given a high-fat diet. A shown in Figure 2C, they gained body weight less significantly than controls. Serum lipid analyses indicated that the dyslipidemia caused by high-calorie diet was significantly restored by the iBA transplantation (Figure 2D).

Next, experiments were performed to confirm the effect of iBAs on metabolic aberration using a different mouse model, i.e., type 2 diabetic KK-Ay mice (Kennedy et al., 2010, Tomino, 2012, O’Brien et al., 2013). iPSCs were established from fibroblasts of KK-Ay mice (Figure S2), and iBAs induced from the iPSCs were transplanted into syngenic hosts. As shown in Figures 2E and 2F, the iBA-transplanted mice showed significantly lower body weight gain and serum glucose elevation. The iBA transplantation also reduced urine glucose (Figure 2G) and serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides (TGs), phospholipid, and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) (Figure 2H). Although HDL cholesterol level was not significantly affected, the ratio of HDL/total cholesterol was remarkably increased by the iBA transplantation (Figure 2H).

These results demonstrated that iBAs were metabolically active in vivo and significantly suppressed diet-induced obesity, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes.

Direct Conversion of Fibroblasts into BAs

We next tried to directly convert human fibroblasts into BAs. Retroviral vectors containing the PRDM16 (P) and C/EBP-β (C) genes, as well as those containing the reprogramming factor genes (Klf4 [K], L-MYC [L], C-MYC [M], and Glis1 [G]) were prepared, and various combinations of the retroviral vectors were infected into dermal fibroblasts. Oil Red O staining suggested that some combinations of genes, such as PCLMG, CLMG, PCLM, CLM, and CM, strongly evoked fibroblasts to accumulate lipid droplets (Figure S3A).

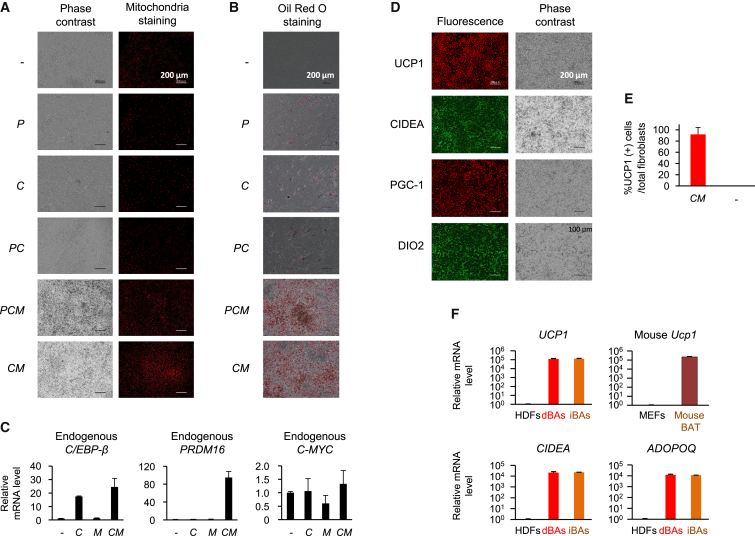

Thus, we transduced PRDM16, C/EBP-β, and/or C-MYC genes to the cells and examined the efficiency of induction of BA-like characteristics in more detail. The results are shown in Figures 3A and 3B. Oil Red O-positive lipid droplets were only faintly induced in C- and PC-transduced cells. Meanwhile, the PCM mixture more drastically induced accumulation of the lipid depots and an increase in number of mitochondria in the cells. Interestingly, the combination CM converted fibroblasts into cells with a BA-like phenotype at the highest rate.

Figure 3.

Human Dermal Fibroblasts Were Efficiently Converted into BAs by Defined Factors

(A and B) HDFs were transduced with the indicated retroviral vectors, and after culturing for 12 days, cells were subjected to mitochondria staining (A) and Oil Red O staining (B). Original magnification was 100×.

(C) HDFs transduced with C and/or M retrovirus vectors were cultured for 14 days, and mRNA levels for the indicated genes were evaluated by real-time RT-PCR.

(D) CM-transduced HDFs were cultured for 12 days and immunostained with the indicated antibodies (original magnification was 100×; immunostaining images were obtained using haze reduction). In (A) and (D), representative images of three independent experiments (n = 3 cultures per group) are shown.

(E) CM-transduced HDFs and untransduced HDFs were cultured for 12 days and stained with DAPI (nuclear staining) and anti-UCP1 antibody as above. Proportions of UCP1-staining cells are shown as average ± SD (representative of three independent experiments; n = 3 cultures per group).

(F) RNA was obtained from HDFs, iBAs, and CM-infected HDFs cultured for 12 days (dBAs). Relative mRNA levels for the indicated genes were evaluated.

In (C) and (F), values (average ± SD) were normalized to β-ACTIN mRNA and expressed relative to values for the HDFs (set to 1.0). The experiments were repeated more than three times. See also Figures S3 and S4.

Cells transduced with C and/or M were tested for mRNA expression of endogenous PRDM16, C/EBP-β, and C-MYC genes. Exogenous C/EBP-β induced endogenous C/EBP-β, whereas both C/EBP-β and C-MYC were required for induction of PRDM16 (Figure 3C). Thus, CM transduction induced endogenous C/EBP-β and PRDM16 gene expression, which may have caused conversion of fibroblasts into BA-like cells. Fibroblasts expressed endogenous c-myc mRNA at low level, which was not affected by transduction with C and/or M.

The CM-transduced cells were referred to as directly converted BAs (dBAs) and examined in more detail. Immunostaining showed that the dBAs highly expressed BA-specific proteins (Figure 3D). It was found that 92.1% ± 12.1% of the fibroblasts became UCP1-positive cells (Figure 3E). The cells expressed mRNA for UCP1, CIDEA, and ADIPOQ at extremely high levels compared with fibroblasts. The mice BAT expressed comparable levels of mRNA for these genes (Figure 3F).

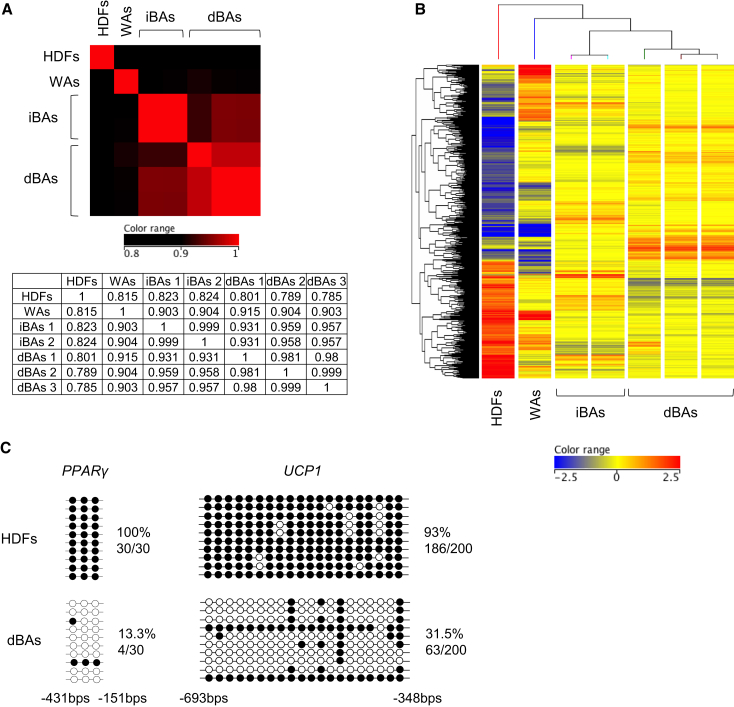

We also performed DNA microarray analysis to examine genome-wide mRNA expression profiles. Hierarchical clustering analysis revealed that gene expression profile of dBAs was closer to that of iBAs than those of fibroblasts and WAs (Figures 4A and 4B).

Figure 4.

Characterization of dBAs

HDFs were transduced with CM retroviruses as in Figure 3D, and after culturing for 12 days, the cells were uses as dBAs.

(A and B) RNA was extracted from HDFs, WAs, iBAs (obtained from two independent induction experiments), and dBAs (obtained from three independent induction experiments). DNA microarray analyses were performed. Heatmap and correlation coefficient values for all genes are shown (A). Among 29,096 genes tested, 3,517 genes were shown differentially expressed among the cells (greater than three folds), and heatmap and hierarchical clustering analysis of the differentially expressing genes are shown (B). Red and blue colorations indicate increased and decreased expression, respectively.

(C) Genomic DNA was extracted from HDFs and human dBAs and tested for CpG methylation at the PPAR-γ and UCP1 gene upstream regions (n = 10 plasmid clones per group). The experiments were repeated more than three times.

See also Table S2.

We analyzed the effects of CM transduction on the epigenetic status of BA-related genes. In untransduced fibroblasts, genomic DNA was heavily methylated at CpG dinucleotides at the upstream regions of the PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ) and UCP1 gene loci. In sharp contrast, the CpG sequences were mostly unmethylated 12 days after CM transduction (Figure 4C).

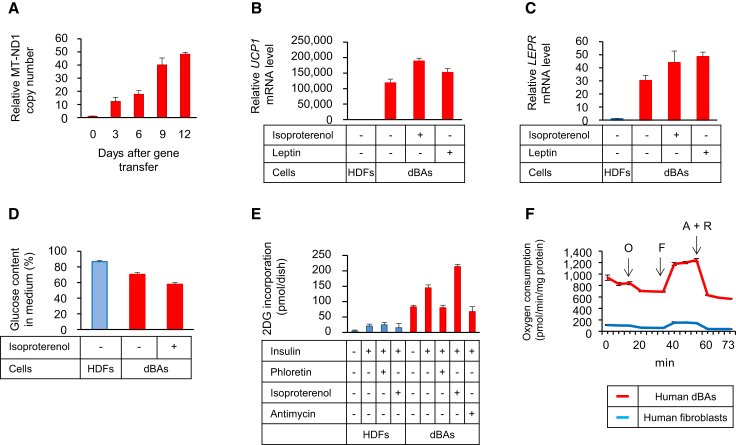

Functional features of the dBAs were assessed in vitro. As shown in Figure 5A, the copy number of mitochondrial DNA rapidly increased after CM transduction of fibroblasts, which was consistent with an increase in the number of mitochondria (Figure 3A). Addition of leptin and isoproterenol prompted dBAs to highly express mRNA for UCP1 and the leptin receptor (LEPR) (Figures 5B and 5C). dBAs consumed more glucose than fibroblasts, as indicated by the decrease in glucose content in the culture medium (Figure 5D) and uptake of 2-deoxy glucose (2DG) (Figure 5E). The glucose uptake by dBAs was further elevated after stimulation with insulin, which in turn could be inhibited by phloretin, an inhibitor of the glucose transporter, and antimycin, a suppressor of the electron transport chain. dBAs also showed a higher rate of oxygen consumption than fibroblasts (Figure 5F). The oxygen uptake of dBAs was only partially suppressed by oligomycin, an inhibitor of mitochondrial ATP synthase, demonstrating a high rate of uncoupling respiration. It is virtually impossible to obtain viable BAs from human BAT and culture them for functional analyses; therefore, metabolic activity of human BAs has not been fully evaluated. Our results indicated that human dBAs were highly active in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative metabolism.

Figure 5.

Metabolic Features of dBAs

(A) DNA was extracted from CM-transduced HDFs on the indicated days after transduction. Relative copy number of MT-ND1 was determined by real-time PCR.

(B and C) Cells were stimulated with 100 nM leptin for 6 hr or 1 μM isoproterenol for 2 hr. mRNA for UCP1 (B) and LEPR (C) genes were evaluated.

(D) HDFs, dBAs, and dBAs pre-stimulated with isoproterenol were cultured for 24 hr. Glucose content in the supernatant was determined.

(E) Cells were cultured with or without insulin, whereas some cell aliquots were also treated with the indicated reagents. Thirty minutes after addition of 2DG, incorporated 2DG was evaluated.

(F) Oxygen consumption of the indicated cells was evaluated as in Figure 1E.

Values in (A)–(F) are average ± SD (n = 3 cultures per group). The experiments were repeated more than three times.

We examined whether dBAs were actually converted from fibroblasts without passing an immature pluripotent stage. After transduction with CM, fibroblasts were immunostained with anti-NANOG antibody every day during days 1–5 post-transduction. No significant expression of NANOG, which is an essential transcription factor for pluripotent cells, was detected at all during the experimental periods, whereas UCP1 was detected as early as day 5 (Figure S3B). These results suggest that dBAs were directly converted from fibroblasts.

The dBAs expressed retroviral C/EBP-β and C-MYC transgenes at high levels (Figure S4A). We assessed whether continuous expression of these exogenous genes is required for dBAs to maintain their phenotype. Using the Tet-On promoter system, fibroblasts were allowed to express retroviral C and M genes only during the first 20 days, followed by culturing for another 22 days without induction of the exogenous gene expression. Because the Tet-On promoter achieved relatively low levels of expression of C and M genes even in the presence of doxycycline, efficiency of conversion was lower than that obtained by conventional CM retrovirus vectors; thus, we picked up colonies with lipid droplets for qRT-PCR analysis. As results, the cells retained the BA-like character on day 42 (Figures S4B and S4C), although they no longer expressed exogenous C and M genes (Figure S4A). Therefore, dBAs, once established by transient CM expression, may have developed intrinsic program that stably maintained the dBA phenotype even in the absence of the exogenous gene expression.

We tried to convert mouse fibroblasts into dBAs. Interestingly, transduction of CM that successfully converted human fibroblasts into dBAs failed to significantly induce Ucp1 mRNA in MEFs (mouse embryonic fibroblasts) per se, whereas PCL was found the most-effective gene combination for mouse dBA direct reprogramming (Figure S5A). Transduction of CM and CL induced expression of PRDM16 in human (Figures 3B and S5B, lower), but not mouse (Figure S5B, upper), fibroblasts, which may be the reason why exogenous Prdm16 is required for the conversion of mouse fibroblasts into dBAs. The PCL-transduced cells (mouse dBAs) expressed Ucp1 and Cidea mRNA as strongly as mouse BAT (Figure S5C) and shared similar gene expression profiles with mouse BAT, but not with MEFs (Figure S5D). The mouse dBAs also showed high rates of basal oxygen consumption and uncoupling respiration (Figure S5E).

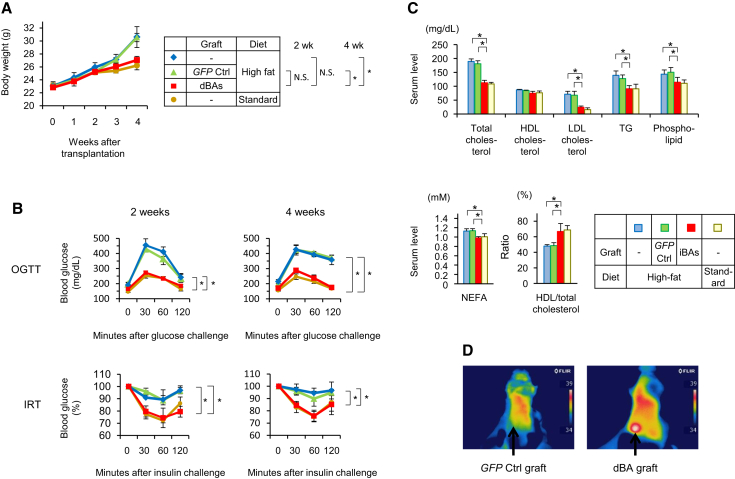

dBAs Significantly Improved Metabolic Traits In Vivo

Mouse dBAs were subcutaneously transplanted into syngenic mice, and high-fat diet was given to them. The diet-induced obesity was remarkably prevented by the dBA transplantation (Figure 6A). Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity were significantly improved as early as 2 weeks after the dBA transplantation (Figure 6B), when body weights of mice did not significantly differ among groups (Figure 6A), strongly suggesting that the improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity was not secondarily resulted from the suppression of body weight gain. Serum lipid analyses indicated that dBA transplantation reduced total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, TG, phospholipid, and NEFA levels and significantly elevated the HDL/total cholesterol ratio (Figure 6C). The graft area showed high temperature (Figure 6D), suggesting that the dBAs may have expended the dietary energy as heat. Immunohistochemical analysis of graft tissue demonstrated tyrosine hydroxylase-positive cells (Figure S6A), strongly suggesting sympathetic innervation of the dBA graft.

Figure 6.

dBAs Suppressed Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice

C57BL/6 MEFs were transduced with either PCL or GFP retroviral vectors (day −12), and the resultant cells (dBAs and GFP control, respectively) were subcutaneously transplanted into syngenic mice (day 0). These mice, as well as non-transplanted mice, were housed on either standard- or high-calorie diet.

(A) Body weights of the mice are shown.

(B) Two and four weeks after transplantation, oral glucose tolerance test (upper) and insulin resistance test (lower) were performed.

(C) Serum lipid concentrations on day 28 are shown. Values are average ± SD for one out of two independent experiments (n = 8 mice per group). ∗p < 0.05 (two-sided Student’s t test).

(D) Two weeks after transplantation, mice were exposed to 4C for 2 hr. Shown are thermographic images of the representative mice (n = 4 mice per group). The experiments were repeated more than twice.

See also Figures S5 and S6A.

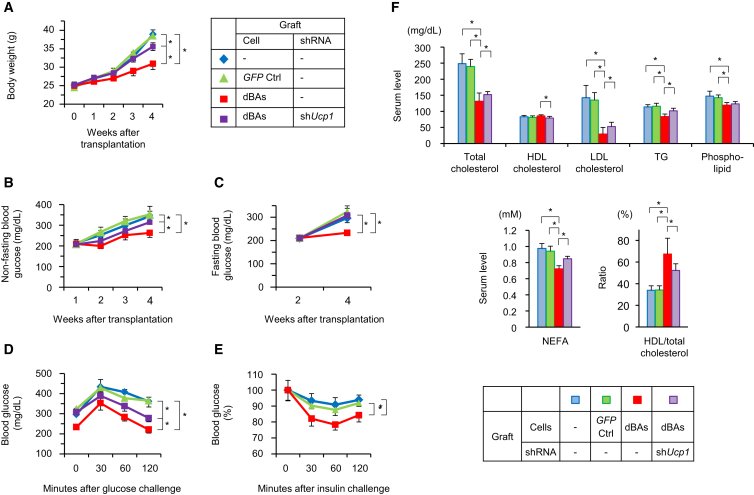

Finally, we investigated whether dBA transplantation affected insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes. KK-Ay diabetic mice were transplanted with dBAs obtained from syngenic MEFs. The mice showed significantly lower body weight gain (Figure 7A) and serum glucose levels (Figures 7B and 7C) compared with controls. The glucose tolerance of diabetic mice was significantly improved by the dBA transplantation, which also reduced insulin resistance (Figures 7D and 7E). Serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, TG, phospholipid, and NEFA were reduced by the dBAs as well (Figure 7F).

Figure 7.

dBAs Suppressed Diabetes in Mice

KK-Ay MEFs were transduced with either PCL or GFP retroviral vectors (day −12) to obtain dBAs and GFP control cells, respectively. Other cells were transduced with both PCL and shUCP1. The cells were subcutaneously transplanted into syngenic mice (day 0).

(A–C) Body weights of mice (A) as well as fasting and non-fasting serum glucose levels (B and C) of the mice are shown.

(D–F) On day 28, oral glucose tolerance test (D) and insulin resistance test (E) were performed, while serum lipid concentrations were evaluated (F). Values are average ± SD (n = 8 mice per group). The experiments were repeated more than twice.

In an attempt to clarify the mechanism of suppression of insulin resistance by dBAs, some mice were grafted with dBAs that had been transfected with shRNA specific for Ucp1. The shRNA treatment suppressed Ucp1 mRNA to approximately 14% (Figure S6B). As result, the silencing of Ucp1 significantly cancelled the effects of dBAs on body weight gain (Figure 7A), serum glucose levels (Figures 7B and 7C), glucose tolerance (Figure 7D), and dyslipidemia (Figure 7F).

Discussion

Two different lineages of BAs have been known. Classical BAs are derived from Myf-5 expressing common progenitors for myoblasts and BAs (Seale et al., 2008). The myoblastic precursors originate from the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). PRDM16 is crucially involved in the differentiation of myoblasts into classical BAs (Seale et al., 2007, Seale et al., 2008, Kajimura et al., 2009). PRDM16 interacts with C/EBP-β to form an active transcription complex that enhances expression of genes involved in brown adipogenesis, such as PGC-1α (Kajimura et al., 2009). Ahfeldt et al. (2012) induced human iPSCs to differentiate into MSCs and subsequently transduced them with the PPAR-γ2 and C/EBP-β (with/without PRDM16) genes. The resultant cells expressed UCP1 approximately 20-fold higher than WAs (Ahfeldt et al., 2012). Nishio et al. (2012) cultured human iPSCs and ESCs with a cocktail of hematopoietins and succeeded in inducing the classical BAs. The cells improved oral fat and glucose tolerance of normal mice 16 hr after transplantation (Nishio et al., 2012). Our iBAs were induced from iPSCs via a myoblast-like state, and only PRDM16 was required for the conversion of the myoblast-like cells into iBAs (Figure 1), which is consistent with previous literature on the contribution of PRDM16 in differentiation of classical BAs (Seale et al., 2007, Seale et al., 2008, Kajimura et al., 2009).

Meanwhile, inducible BAs, also referred to as brite (brown in white), beige, or brown-like adipocytes, are directly converted from MYF-5-negative adipocytes in white lipid depots (Giralt and Villarroya, 2013, Lo and Sun, 2013, Chechi et al., 2013). The induction of the BA-like phenotype (browning) is caused by chronic cold exposure, hormonal or β-adrenergic signals, or pharmacological activation of PPAR-γ. Again, PRDM16 plays a crucial role in the browning; it binds to CTBP1 (C-terminal-binding protein 1) and CTBP2 to repress transcription of various WA-specific genes, whereas an association of PRDM16 with PGC-1α and PGC-1β results in induction of genes involved in BA differentiation (Kajimura et al., 2008). It is also been shown that the vascular endothelium of adipose tissue can transdifferentiate into WAs and BAs (Tran et al., 2012).

Unlike these physiological differentiation pathways of BAs, i.e., differentiation of classical BAs from MSCs via myoblasts, and transdifferentiation of inducible BAs from WAs, we succeeded in artificial conversion of unrelated somatic cells into highly functional BAs. In a previous report, not only myoblasts but also immortalized and normal fibroblasts were co-transduced with PRDM16 plus C/EBP-β genes (Kajimura et al., 2009). After the transduction, the immortalized mouse fibroblasts expressed Ucp1 mRNA approximately 1,000-fold higher than untransduced cells, whereas normal human and mouse fibroblasts had approximately 7 and 20 times higher expression levels than untransduced ones, respectively. Mouse BAT expresses approximately 200,000 times higher Ucp1 mRNA compared with fibroblasts that express this gene very faintly (Figure 3F). Our experiments also showed that PRDM16 plus C/EBP-β (PC) very faintly induced the BA-like phenotype in human fibroblasts (Figures 3A and 3B). In contrast, the dBAs induced by C/EBP-β and C-MYC (CM) expressed UCP1 mRNA approximately 100,000-fold higher than untransduced fibroblasts (Figure 3F) and showed a much more significant BA-like phenotype than PC-transduced cells (Figures 3A and 3B). Thus, C-MYC must have played an indispensable role in the reprogramming of normal fibroblasts into fully functional dBAs. C-MYC is one of the Yamanaka’s reprogramming factors (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006, Takahashi et al., 2007), and although it is not a prerequisite for iPSCs generation (Nakagawa et al., 2008), C-MYC is shown to play important roles in direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts into neural stem cells (Han et al., 2012, Thier et al., 2012) and chondrocytes (Hiramatsu et al., 2011). In our procedure, C-MYC induced PRDM16 gene in cooperation with C/EBP-β, which may be crucial for reprogramming of fibroblasts into dBAs (Figure 3C).

The present study showed that transplantation of iBAs and dBAs markedly reduced diet-induced obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance in mice (Figures 2, 6, and 7). The dBAs controlled insulin resistance in an UCP1-dependent fashion, strongly suggesting the UCP1-mediated energy expenditure as the principal mechanism underlying the control of insulin resistance (Figure 7). Gunawardana and Piston (2012) transplanted BAT from mouse embryos into type 1 diabetic mice and showed significant suppression of diabetic markers. Stanford et al. (2013) transplanted BAT from the interscapular region of adult mice into syngenic mice and found significant improvement in the high-calorie-diet-associated metabolic traits. The present study demonstrated artificial generation of highly functional BAs capable of controlling insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

The present study suggests the possibility of a cell therapy for the metabolic diseases using tailor-made BAs. Such regenerative therapies may be particularly efficacious to those patients who have lost functional BAT due to aging and/or progression of metabolic diseases (Saito et al., 2009, Ouellet et al., 2011).

Experimental Procedures

Cells

aHDF (normal human dermal fibroblasts) was purchased from Kurabo (cat no. KF-4109), whereas the PLAT-GP and PLAT E packaging cell lines were purchased from Cell Biolabs (cat nos. VPK-305 and VPK-303, respectively). They were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) (Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 mM non-essential amino acids (NEAA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Complete medium). SNL feeder cells were purchased from DS Pharma Biomedical (cat no. EC07032801-F0). Human iPSCs were established from NHEK (human epidermal keratinocytes; cat no. FC-0025; Kurabo) by transfecting Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-based episomal vectors encoding OCT3/4, KLF-4, SOX2, C-MYC, and LIN28 as described (Takahashi et al., 2007). KK-Ay mouse iPSCs were established from tail tip fibroblasts by transduction with retroviral vectors containing murine Oct3/4, Klf-4, Sox2, and C-myc genes (Figure S3). Every cell line had been determined to be negative for mycoplasma contamination.

Retroviral Vectors

The coding sequences for human PRDM16 and C/EBP-β genes (DNAFORM cDNA clone library; DNAFORM) were amplified by RT-PCR and cloned into EcoRI-digested pMXs vector (Cell Biolabs). pMXs vectors containing human Krueppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), Glis family zinc finger 1 (GLIS1), C-MYC, and L-MYC genes were a kind gift of Professor S. Yamanaka (Kyoto University). PLAT-GP packaging cells (5.5 × 106) were plated on geratin-coated 10-cm dishes and cultured overnight. They were co-transfected with pCMV-VSV-G and one of the pMX plasmids containing transcriptional factor genes as above using the X-treme Gene 9 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) diluted in Opti-MEM. Twenty-four hours later, the culture supernatant was replaced by anti-biotic free culture medium. After culturing for another 24 hr, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45-μm pore-size filter. The coding sequences for mouse Prdm16 and C/ebp-β genes (DNAFORM) were amplified by RT-PCR. Ecotrophic retroviral vectors were constructed as above, except that PLAT-E packaging cells were used instead of PLAT-GP. The GFP retroviral vector was kindly provided by Professor S. Yamanaka of Kyoto University.

Induction of BAs from iPSCs

Human iPSCs were induced to differentiate into embryoid bodies by culturing in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 25 μM RA in nonadherent culture dishes. On day 7, cells were collected, allowed to adhere to plastic dishes, and cultured for another 10 days in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μM RA. Cells were then transduced with the retroviral vector encoding human PRDM16, followed by further culturing in BA1 medium (10% FBS, 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxantine [IBMX], 1 μM dexamethasone, 125 nM indomethacin, 850 nM insulin, 1 nM triiodothyronine [T3], and 1 μM rosiglitazone) for 2 days and subsequently in BA2 medium (10% FBS, 850 nM insulin, 1 nM T3, and 1 μM rosiglitazone) for 8 days. Mouse iPSCs were cultured in DMEM/10% FBS under nonadherent conditions. RA was added to the culture medium to a final concentration of 25 μM (days 3–5) and 50 μM (days 5–7) to obtain embryoid bodies. On day 7, cells were collected and cultured for another 10 days in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 μM RA under adherent conditions. The cells were transfected with an episomal vector containing the mouse PRDM16 gene by electroporation, followed by further culturing in BA1 medium for 2 days and in BA2 medium for 8 days.

Direct Conversion of Fibroblasts into BAs

Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) were seeded onto culture dishes or plates at a density of 1.5–2.0 × 104 cells/ml. On the next day, cells were transduced with various combinations of retroviral vectors (Figures 3A–3B, S3A, and S5) or a mixture of C/EBP-β and C-MYC retroviral vectors (CM) (Figures 3C–3E, 4, 5, and S3B) in the presence of 4 μg/ml polybrene (day 0). On day 1, culture supernatant was replaced by fresh type 1 medium (10% FBS, 850 nM insulin, 1 nM T3, 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM dexamethasone, 125 nM indomethacin, and 1 μM rosiglitazone). After culturing for 2 days, culture supernatant was replaced by type 2 medium (10% FBS, 850 nM insulin, 1 nM T3, and 1 μM rosiglitazone). Culture medium was refreshed once every 2 days. MEFs derived from C57BL/6 and KK-Ay mice were transduced with various combinations of retroviral vectors (Figure S5A) or a mixture of Prdm16, C/ebp-β, and L-myc retroviral vectors (PCL) (Figures 6, 7, and S5B–S5E) as above.

Cell Staining

For mitochondrial staining, MitoTracker Red probe (Invitrogen) was added to the culture to a final concentration of 200 nM and cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% humidified air for 15 min. For Oil Red O staining, cells were washed with PBS (−) and fixed with 60% isopropanol. After staining with the Oil Red O solution (0.048% w/v Oil Red O in 60% isopropanol), cells were washed with 60% isopropanol followed by washing with distilled water.

Immunostaining

The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were stained with the following antibodies, all at the optimally titrated dose. To stain human UCP1 and DIO2, cells were incubated with goat anti-human UCP1 (cat no. PAB6905; Abnoba) and goat anti-human DIO2 (cat no. NBP1-00178; Novus Biologicals), respectively, followed by washing and incubation with secondary antibody (either Alexa-488-labeled anti-goat IgG [cat no. A11070; Invitrogen] or PE-labeled anti-goat IgG [cat no. PA1-29953; Thermo Scientific] antibody). To stain human CIDEA, rabbit anti-human CIDEA (cat no. NBP1-46987; Novus Biologicals) and Alexa-488-labeled anti-rabbit Ig (cat no. A11070; Invitrogen) antibodies were used. Human PGC1 was stained using rabbit anti-human PGC1 (cat no. NBP1-04676; Novus Biologicals) and PE Cy5-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (cat no. sc-45110; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. To stain mouse UCP1, CIDEA, and DIO2, cells were incubated with anti-mouse UCP1 (cat no. MAB6158; R&D Systems), rabbit anti-mouse CIDEA (cat no. PAB11960; Abnoba), and goat anti-mouse DIO2 (cat no. NBP1-0017; Novus Biologicals) antibodies, followed by staining with CF488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (cat no. 20014; Biotium), Alexa-488-labeled anti-rabbit Ig (cat no. A11070; Invitrogen), and PE-conjugated anti-goat IgG (cat no. sc45110; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies, respectively.

Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using ISOGEN II (Nippon Gene) and reverse transcribed using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO). In some experiments, dBAs were stimulated with 100 nM leptin for 24 hr or 1 μl isoproterenol for 2 hr before RNA extraction. RNA was also extracted from BAT isolated from the posterior cervical region of C57Bl/6 mice. Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using Real-time PCR Master Mix (TOYOBO) and matching probes and primers on a 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). All values were normalized with respect to the β-actin mRNA level in each sample and expressed relative to the corresponding value in gingival fibroblasts. The primer sequences are shown in Table S1.

DNA Microarray Analysis

For human cells, RNA was obtained from WAs, iBAs, and dBAs, and after reverse-transcription, microarray analyses were performed using GeneChip human Gene 1.0 ST (Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. For mouse cells, RNA obtained from MEFs, BAT, and dBAs was reverse-transcribed and analyzed using GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array. Scanned data were analyzed using Expression Console (Affymetrix) and GeneSpring Ver.12.6 (Agilent Technologies) software.

Bisulfite Sequencing

Bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA was performed using MethylCode Bisulfite Conversion Kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The sequences corresponding to the human UCP-1 gene upstream region (−693 to −348 bases relative to the transcription start site) and the PPARγ gene upstream region (−431 to −151 bases relative to the transcription start site) were amplified by PCR using primers described in Table S2. The resultant PCR product was cloned into the pTA2 vector (TOYOBO). Ten randomly selected clones of each sample were sequenced using the T7 and T3 universal primers.

Mitochondria DNA Evaluation

Real-time PCR was performed using the 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The matching primers and dye probe for the MT-ND1 (Hs02596873_s1) and β-ACTIN (Hs00357333_g1) were purchased from Applied Biosystems. Copy numbers were quantified by RQ software (Applied Biosystems).

Metabolic Analyses

HDFs were transduced with CM retrovirus vectors as above. After cultured for 12 days, the cells were used as dBAs. To assess glucose consumption, culture supernatants of HDFs, un-stimulated dBAs, and dBAs pre-stimulated with 1 μM isoproterenol (LKT Laboratories) for 2 hr were replaced by fresh complete medium. Before and 24 hr after culture under the standard conditions, glucose concentrations in the culture supernatants were measured by the glucose B test (Wako). To determine glucose uptake, culture supernatants of HDFs and dBAs were replaced by the Krebs Ringer Phosphate HEPES buffer (1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 118 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, and 30 mM HEPES [pH 7.5]). Eighteen min after addition of 1 μM insulin (Cell Science & Technology Institute), 2DG was added to the culture to a final concentration of 1 mM, and 30 min later, 2DG uptake was evaluated using the 2-DG Uptake Measurement Kit (CSR). Some aliquots of cells were incubated with 1 μM Antimycin (Enzo Life Science) or 1 μM isoproterenol for 4 hr before the addition of insulin, whereas other aliquots of cells were incubated with 200 μM phloretin (Wako) for 2 min before the addition of 2DG. Oxygen consumption was determined using Extracellular Flux Analyzer XF96 instrument (Seahorse Bioscience). Briefly, mitochondrial biogenesis was profiled by serially adding perturbation agents, i.e., 2 μM oligomycin (Sigma; cat no. 04876), 0.5 μM FCCP (carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone; Sigma; cat no. C2920), and 3 μM antimycin A (Sigma; cat no. A8674), and 1 μM rotenone (Sigma; cat no. R8875) to the cells.

Transplantation

Every animal experiment was approved by the institutional Animal Experiment Committee, and care of the animals was in accordance with institutional guidelines. Male C57BL/6 and KK-Ay/Tajcl mice (Shimizu Laboratory Suppliers) at 8 weeks of age were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital. In iBA transplantation experiments, the iBAs in two confluent 100-mm dishes were resuspended in 25 μl medium/75 μl Matrigel (BD Bioscience) and subcutaneously transplanted to the flank of syngenic mice. As control, cells were transduced with GFP retroviral vector instead of Prdm16 retroviral vector and transplanted to mice as above, whereas the other control group was not transplanted. In dBA transplantation experiments, dBAs that had been induced from MEF by PCL retroviral vector transduction, and MEF that had been transduced with GFP retroviral vector as control, were transplanted to syngenic mice as above.

Diet-Induced Obesity Mouse Model

Mice were housed on high-fat diet (Quick Fat; CLEA Japan) or regular chow (CE-2; CLEA Japan) as control. Diet composition (w/w %) of the high-fat diet was as follows: 24.0% crude protein; 14.6% crude fat; 2.7% crude fiber; 5.1% crude ash; 46.7% NFE; and 7.3% moisture (Katakura et al., 2012). Total calorie of the high-fat diet was 415.1 kcal/100 g. The regular chow was composed of 24.9% (w/w) crude protein, 4.6% crude fat, 4.1% crude fiber, 6.6% crude ash, 51.0% NFE, and 8.9% moisture with total calories of 344.9 kcal/100 g. Any significant difference was not observed among the amounts of food intake of all mouse groups fed high-fat diet during the experimental periods in all experiments (Figure S7).

Thermography and Metabolic Analyses of Mice

Thermographic imaging was obtained using a thermal imaging camera (Fliar Systems). Serum lipids were evaluated using the NEFA C Test (Wako), Triglyceride E Test (Wako), Phospholipids C Test (Wako), HDL-cholesterol E Test (Wako), and Total Cholesterol E Test (Wako). Blood glucose levels were measured using GluTest (Sanwa Kagaku). For the oral glucose tolerance test, mice were administered with 50 mg of glucose via a gastric catheter. Before and 30, 60, and 120 min after the administration, blood glucose was evaluated as above. For the insulin-resistant test, mice were intraperitoneally administered with 0.0125 U of insulin. Before and 30, 60, and 120 min after the administration, blood glucose was determined.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as average ± SD. Data in each group distributed normally, and variance was similar between the groups that were statistically compared. Statistical significance was analyzed by Student’s t test (two-sided). A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. No statistical analysis was used to predetermine sample size. Experiments were performed in randomized and non-blind fashion. No samples or animals were excluded from the analyses. The data met the assumptions of the tests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wilfred Germeraad for critical reading of the manuscript. The present study was supported by grants from the Japan Science and Technology Agency (PRESTO and A-Step); the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; and the ITC-PAC.

Published: September 10, 2015

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Supplemental Information includes seven figures and three tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.08.007.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the microarray data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE52817.

Supplemental Information

References

- Ahfeldt T., Schinzel R.T., Lee Y.K., Hendrickson D., Kaplan A., Lum D.H., Camahort R., Xia F., Shay J., Rhee E.P. Programming human pluripotent stem cells into white and brown adipocytes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:209–219. doi: 10.1038/ncb2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiazzo M., Dell’Anno M.T., Dvoretskova E., Lazarevic D., Taverna S., Leo D., Sotnikova T.D., Menegon A., Roncaglia P., Colciago G. Direct generation of functional dopaminergic neurons from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nature. 2011;476:224–227. doi: 10.1038/nature10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chechi K., Carpentier A.C., Richard D. Understanding the brown adipocyte as a contributor to energy homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;24:408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypess A.M., Lehman S., Williams G., Tal I., Rodman D., Goldfine A.B., Kuo F.C., Palmer E.L., Tseng Y.H., Doria A. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1509–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesta S., Tseng Y.H., Kahn C.R. Developmental origin of fat: tracking obesity to its source. Cell. 2007;131:242–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt M., Villarroya F. White, brown, beige/brite: different adipose cells for different functions? Endocrinology. 2013;154:2992–3000. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardana S.C., Piston D.W. Reversal of type 1 diabetes in mice by brown adipose tissue transplant. Diabetes. 2012;61:674–682. doi: 10.2337/db11-0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D.W., Tapia N., Hermann A., Hemmer K., Höing S., Araúzo-Bravo M.J., Zaehres H., Wu G., Frank S., Moritz S. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into neural stem cells by defined factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu K., Sasagawa S., Outani H., Nakagawa K., Yoshikawa H., Tsumaki N. Generation of hyaline cartilaginous tissue from mouse adult dermal fibroblast culture by defined factors. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:640–657. doi: 10.1172/JCI44605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P., He Z., Ji S., Sun H., Xiang D., Liu C., Hu Y., Wang X., Hui L. Induction of functional hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:386–389. doi: 10.1038/nature10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ieda M., Fu J.D., Delgado-Olguin P., Vedantham V., Hayashi Y., Bruneau B.G., Srivastava D. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagawa K., Ieda M. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts into cardiac myocytes. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2013;6:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagawa K., Miyamoto K., Yamakawa H., Muraoka N., Sadahiro T., Umei T., Wada R., Katsumata Y., Kaneda R., Nakade K. Induction of cardiomyocyte-like cells in infarct hearts by gene transfer of Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5. Circ. Res. 2012;111:1147–1156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.271148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura S., Seale P., Tomaru T., Erdjument-Bromage H., Cooper M.P., Ruas J.L., Chin S., Tempst P., Lazar M.A., Spiegelman B.M. Regulation of the brown and white fat gene programs through a PRDM16/CtBP transcriptional complex. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1397–1409. doi: 10.1101/gad.1666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura S., Seale P., Kubota K., Lunsford E., Frangioni J.V., Gygi S.P., Spiegelman B.M. Initiation of myoblast to brown fat switch by a PRDM16-C/EBP-beta transcriptional complex. Nature. 2009;460:1154–1158. doi: 10.1038/nature08262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katakura M., Hashimoto M., Tanabe Y., Shido O. Hydrogen-rich water inhibits glucose and α,β -dicarbonyl compound-induced reactive oxygen species production in the SHR.Cg-Leprcp/NDmcr rat kidney. Med. Gas Res. 2012;2:18. doi: 10.1186/2045-9912-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A.J., Ellacott K.L., King V.L., Hasty A.H. Mouse models of the metabolic syndrome. Dis. Model. Mech. 2010;3:156–166. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Efe J.A., Zhu S., Talantova M., Yuan X., Wang S., Lipton S.A., Zhang K., Ding S. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7838–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Ambasudhan R., Ding S. Direct lineage reprogramming to neural cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2012;22:778–784. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontani Y., Wang Y., Kimura K., Inokuma K.I., Saito M., Suzuki-Miura T., Wang Z., Sato Y., Mori N., Yamashita H. UCP1 deficiency increases susceptibility to diet-induced obesity with age. Aging Cell. 2005;4:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo K.A., Sun L. Turning WAT into BAT: a review on regulators controlling the browning of white adipocytes. Biosci. Rep. 2013;33 doi: 10.1042/BSR20130046. pii: e00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A. Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1079–1088. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M., Koyanagi M., Tanabe K., Takahashi K., Ichisaka T., Aoi T., Okita K., Mochiduki Y., Takizawa N., Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y.J., Song K., Luo X., Daniel E., Lambeth K., West K., Hill J.A., DiMaio J.M., Baker L.A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E.N. Reprogramming of human fibroblasts toward a cardiac fate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:5588–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301019110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio M., Yoneshiro T., Nakahara M., Suzuki S., Saeki K., Hasegawa M., Kawai Y., Akutsu H., Umezawa A., Yasuda K. Production of functional classical brown adipocytes from human pluripotent stem cells using specific hemopoietin cocktail without gene transfer. Cell Metab. 2012;16:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien S.P., Smith M., Ling H., Phillips L., Weber W., Lydon J., Maloney C., Ledbetter S., Arbeeny C., Wawersik S. Glomerulopathy in the KK.Cg-A(y) /J mouse reflects the pathology of diabetic nephropathy. J. Diabetes Res. 2013;2013:498925. doi: 10.1155/2013/498925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet V., Routhier-Labadie A., Bellemare W., Lakhal-Chaieb L., Turcotte E., Carpentier A.C., Richard D. Outdoor temperature, age, sex, body mass index, and diabetic status determine the prevalence, mass, and glucose-uptake activity of 18F-FDG-detected BAT in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:192–199. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet V., Labbé S.M., Blondin D.P., Phoenix S., Guérin B., Haman F., Turcotte E.E., Richard D., Carpentier A.C. Brown adipose tissue oxidative metabolism contributes to energy expenditure during acute cold exposure in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:545–552. doi: 10.1172/JCI60433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang Z.P., Yang N., Vierbuchen T., Ostermeier A., Fuentes D.R., Yang T.Q., Citri A., Sebastiano V., Marro S., Südhof T.C., Wernig M. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature. 2011;476:220–223. doi: 10.1038/nature10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp B., Plath K. Reprogramming to pluripotency: stepwise resetting of the epigenetic landscape. Cell Res. 2011;21:486–501. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M., Okamatsu-Ogura Y., Matsushita M., Watanabe K., Yoneshiro T., Nio-Kobayashi J., Iwanaga T., Miyagawa M., Kameya T., Nakada K. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58:1526–1531. doi: 10.2337/db09-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P., Kajimura S., Yang W., Chin S., Rohas L.M., Uldry M., Tavernier G., Langin D., Spiegelman B.M. Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007;6:38–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale P., Bjork B., Yang W., Kajimura S., Chin S., Kuang S., Scimè A., Devarakonda S., Conroe H.M., Erdjument-Bromage H. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya S., Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford K.I., Middelbeek R.J., Townsend K.L., An D., Nygaard E.B., Hitchcox K.M., Markan K.R., Nakano K., Hirshman M.F., Tseng Y.H., Goodyear L.J. Brown adipose tissue regulates glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:215–223. doi: 10.1172/JCI62308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo E., Rampalli S., Risueño R.M., Schnerch A., Mitchell R., Fiebig-Comyn A., Levadoux-Martin M., Bhatia M. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to multilineage blood progenitors. Nature. 2010;468:521–526. doi: 10.1038/nature09591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thier M., Wörsdörfer P., Lakes Y.B., Gorris R., Herms S., Opitz T., Seiferling D., Quandel T., Hoffmann P., Nöthen M.M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts into stably expandable neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomino Y. Lessons from the KK-Ay mouse, a spontaneous animal model for the treatment of human type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Nephrourol. Mon. 2012;4:524–529. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran K.V., Gealekman O., Frontini A., Zingaretti M.C., Morroni M., Giordano A., Smorlesi A., Perugini J., De Matteis R., Sbarbati A. The vascular endothelium of the adipose tissue gives rise to both white and brown fat cells. Cell Metab. 2012;15:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marken Lichtenbelt W.D., Vanhommerig J.W., Smulders N.M., Drossaerts J.M., Kemerink G.J., Bouvy N.D., Schrauwen P., Teule G.J. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1500–1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada R., Muraoka N., Inagawa K., Yamakawa H., Miyamoto K., Sadahiro T., Umei T., Kaneda R., Suzuki T., Kamiya K. Induction of human cardiomyocyte-like cells from fibroblasts by defined factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12667–12672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304053110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Kishida T., Sato Y., Nishioka K., Ejima A., Fujiwara H., Kubo T., Yamamoto T., Kanamura N., Mazda O. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts into functional osteoblasts by defined factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:6152–6157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420713112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.