Abstract

Background

The use of standardized assessment tools is an element of evidence-informed rehabilitation, but physical therapists report administering these tools inconsistently poststroke. An in-depth understanding of physical therapists' approaches to walking assessment is needed to develop strategies to advance assessment practice.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to explore the methods physical therapists use to evaluate walking poststroke, reasons for selecting these methods, and the use of assessment results in clinical practice.

Design

A qualitative descriptive study involving semistructured telephone interviews was conducted.

Methods

Registered physical therapists assessing a minimum of 10 people with stroke per year in Ontario, Canada, were purposively recruited from acute care, rehabilitation, and outpatient settings. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were coded line by line by the interviewer. Credibility was optimized through triangulation of analysts, audit trail, and collection of field notes.

Results

Study participants worked in acute care (n=8), rehabilitation (n=11), or outpatient (n=9) settings and reported using movement observation and standardized assessment tools to evaluate walking. When selecting methods to evaluate walking, physical therapists described being influenced by a hierarchy of factors. Factors included characteristics of the assessment tool, the therapist, the workplace, and patients, as well as influential individuals or organizations. Familiarity exerted the primary influence on adoption of a tool into a therapist's assessment repertoire, whereas patient factors commonly determined daily use. Participants reported using the results from walking assessments to communicate progress to the patient and health care professionals.

Conclusions

Multilevel factors influence physical therapists' adoption and daily administration of standardized tools to assess walking. Findings will inform knowledge translation efforts aimed at increasing the standardized assessment of walking poststroke.

Worldwide, 15 million people experience a stroke each year.1 More than half lose their ability to walk independently immediately poststroke.2 Walking is an important function that enables participation in meaningful activities3 contributing to health-related quality of life.4 In neurological populations, walking is a favored method of physical activity; thus, walking limitation poses a barrier to regular exercise.5 A sedentary lifestyle can increase morbidity and the risk of subsequent stroke.6 Recovery of walking ability is cited as a primary rehabilitation goal by individuals poststroke.7

An element of evidence-informed rehabilitation is the use of standardized assessment tools.8 The Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care8,9 suggest that valid and reliable standardized assessment tools be used to assess and monitor patients' abilities and identify the Functional Independence Measure (FIM),10 Alpha FIM,11 Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment (CMSA),12 and Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT)13 as standardized tools for the assessment of gait poststroke. Canada is not the only country with best practice recommendations poststroke. The Netherlands also promotes specific measures of walking poststroke,14 whereas the US, UK, and Australian clinical guidelines all recommend the use of standardized assessment tools to evaluate walking but do not specify which tools.15–17 The appropriate use of relevant standardized assessment tools may enhance the quality of physical therapist services by providing reliable indicators of patient status and guiding selection of relevant treatments.18

Physical therapists inconsistently use standardized assessment tools for walking poststroke. In a survey of 270 physical therapists in Ontario, Canada, self-reported use of the recommended standardized assessment tools for walking poststroke was low.19 The percentage of physical therapists consistently using standardized measures of walking poststroke to evaluate walking, monitor change in walking, formulate a prognosis for walking recovery, and determine readiness for discharge was 44%, 42%, 19%, and 28%, respectively.19 Inconsistent use of standardized assessment tools also has been observed among physical therapists in other countries. In a survey of 167 Dutch physical therapists, only 52% used the core set of standardized assessment tools that were recommended by the Dutch guidelines for stroke rehabilitation.20 In a survey of 762 senior physical therapists in the United Kingdom, with the majority having more than 10 years of experience, 28% used standardized assessment tools that they had created, whereas 22% used no standardized assessment tools.20

A number of factors are considered to influence the use of standardized assessment tools among physical therapists.19,21–24 These factors include characteristics of the measure, clinician, workplace, patient, research, and guidelines. The current literature is limited in its applicability to the context of walking assessment poststroke and the variability across the care continuum. Results of previous survey research19,20 have identified suboptimal levels of use of standardized tools to assess walking and revealed that physical therapists identify a lack of time, knowledge, usefulness, ease of administration, and consensus on what to use to assess walking as barriers to the use of standardized assessment tools to evaluate walking ability. Findings do not provide an in-depth understanding of contextual factors, such as characteristics of the assessment tools or patients that influence walking assessment practice. Use of qualitative research methods can provide an in-depth understanding of phenomena by allowing physical therapists to describe and justify their assessment approach in their own words.

Results from a qualitative study indicated that some physical therapists in neurological rehabilitation do not value the results of standardized assessment tools and place greater importance on information gained from their patients and their clinical knowledge and intuition.25 The therapists felt that standardized assessment tools may not be relevant to their client and may not provide the information needed for treatment.25 Studies to date, however, have not examined physical therapists' perspectives on the use of standardized assessment tools across the continuum of care or walking assessments specifically.

Little attention has been paid to the influence of the health care system on evidence-informed assessment practice. Ontario provides an ideal location to examine this influence, as it was the first Canadian province to implement an organized system of stroke care as part of the Canadian Stroke Strategy (http://www.ontariostrokenetwork.ca/). Ontario initiated the development of the Ontario Stroke System, a coordinated approach to stroke care, in 1997, and by 2008, the Ontario Stroke Network was instituted as the provincial leader for stroke care.26 The province is divided into 11 geographical regions, each with a Regional Stroke Centre or Enhanced District Stroke Centre responsible for coordinating stroke care in that region.27 Each region also contains individuals who serve as credible advisors to provide leadership and knowledge translation initiatives to promote system change and the implementation of stroke care best practices across the continuum of care.28 Examining assessment practices among physical therapists in Ontario provides a unique opportunity to study the influence of this organized system of stroke care.

Thus, the objective of this study was to describe the methods physical therapists in Ontario use to evaluate walking; reasons for selecting those methods; use of assessment results in clinical practice poststroke; and recommendations for measures to use across acute care hospital, rehabilitation hospital, and outpatient settings.

Method

Study Design

A qualitative study using a descriptive approach was conducted.

Participants

Physical therapists were considered eligible if they were registered with the provincial regulatory body (the College of Physiotherapists of Ontario); employed in an acute care hospital, rehabilitation hospital, or outpatient setting; provided services to 10 or more patients with stroke per year; and had more than 5 months of experience treating people with stroke. Participants were excluded if they were known to the interviewer to avoid being unduly influenced by this relationship during the interview.

Sampling and Recruitment

Purposive sampling was undertaken to ensure representation of participants from acute, rehabilitation, and community care settings. Participants were recruited using a variety of methods. An electronic recruitment notice was sent to the Ontario Stroke Network, members of Ontario and Canadian physical therapy associations, and 14 acute care and rehabilitation hospitals across Ontario providing services to people with stroke. Recruitment letters were mailed to 85 physical therapists from the required settings who had participated in a previous study.19 Interested individuals were asked to contact the study coordinator. Following initial contact, a screening email outlining the study and a consent form were sent to potential participants. If therapists met the eligibility criteria outlined in the email and were willing to participate, a telephone interview was scheduled. Recruitment continued until no new themes arose in subsequent interviews.

Data Collection

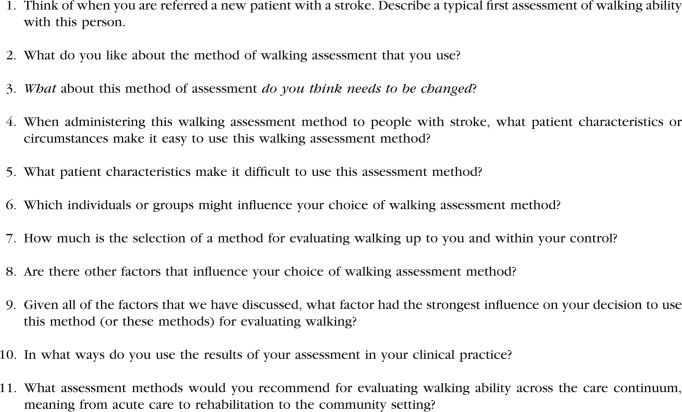

Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to beginning each interview. One semistructured interview exploring physical therapists' experiences assessing walking poststroke was conducted with each participant. Interview questions were developed based on study objectives and knowledge from the literature on factors influencing clinical practice (refer to Appendix for interview guide).

The interview guide was pilot tested with one physical therapist who met the inclusion criteria and was included in the study. After each interview, the interviewer wrote reflective field notes describing the workplace setting and key points raised by participant. Each interview was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each transcript was reviewed for accuracy by listening to audio recordings. Information on sociodemographic and practice characteristics also was collected during the interviews.

Potential Bias

The interviewer's potential bias was that physical therapists should use research findings and guidelines to guide their approach to walking assessment. To diminish the influence of this bias on participants' responses, the interview questions were worded neutrally. For example, the term “walking assessment” was used instead of “walking test” or “outcome measure.”

Data Analysis

Data sources included interview transcripts and field notes. Open coding methods were used. All transcripts and field notes were coded line by line, and nodes were created for each code using NVivo 7 (QSR International [Americas] Inc, Burlington, Massachusetts), a qualitative data analysis software. Five transcripts from participants of each practice setting were coded independently by the first and last authors. Throughout this process, a coding scheme with a description of each code was generated, discussed, revised, and then used to code the remaining transcripts. Once complete, nodes were reviewed and organized into categories. From these categories, overarching themes were determined. All themes were discussed and finalized by all researchers. These themes were distinct and represented all data. Similarities and differences in physical therapists' experiences across the continuum were explored.

Strategies to Ensure Trustworthiness

Credibility was ensured through triangulation, audit trail, and collection of field notes. This study used analyst triangulation.29 Analyst triangulation involved multiple analysts discussing and creating the overarching themes. To maintain an audit trail, records of decisions that were made throughout data collection and analysis were documented.

Role of the Funding Source

This project was funded by a Connaught New Researcher Award, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. Dr Brooks holds a Canada Research Chair. Dr Cameron and Dr Salbach hold Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation Early Researcher and Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Awards.

Results

Of the 114 physical therapists screened for eligibility (including those selected from a previous study), 91 were eligible. Of the 91 individuals who were screened as eligible, 53 did not respond to initial contact, 10 decided not to participate, and 28 were interviewed. Of the 28 participants, 5 were 20 to 29 years of age, 9 were 30 to 39 years of age, 10 were 40 to 49 years of age, 4 were 50+ years of age, and 25 were female. Eighteen therapists had 10 or more years of experience, 8 had 5 years or less of experience, and 3 had between 6 and 9 years of experience with stroke. The mean number of years of clinical experience with stroke was 11.4 (SD=7.0, range=0.4–25). Twenty participants held a bachelor of science degree, 7 had a master of science degree, and 1 had a certificate in physical therapy.

Participants worked in acute care (n=8) (in regional [n=5] and nonregional [n=3] stroke centers), inpatient rehabilitation (n=11), or outpatient care (n=9) (outpatient rehabilitation [n=7] and private practice [n=2]) settings. Interviews lasted an average of 28 minutes (range=14–36). Participants were encouraged to choose a private location for the interview, but this choice of location was not enforced. The location of interviews included at work and not in a private location (n=13), at home (n=8), at work and in a private location (n=5), and in a car (n=1). Location was not recorded for one participant.

Five themes emerged from the data that addressed the study objectives: (1) methods to evaluate walking vary; (2) knowledge about walking assessment methods is derived from formal education, physical therapist students, the provincial stroke network, and research; (3) a hierarchy of factors influences choice of walking assessment method; (4) clinical use of walking assessment results varies; and (5) there is little consensus on ways to assess walking across the care continuum.

Methods to Evaluate Walking Vary

Physical therapists described using a variety of methods to assess walking. Of the 28 participants, 8 (28%) indicated they did not regularly use a standardized tool to assess walking ability poststroke. Sixty-two percent of physical therapists in acute care, 18% in rehabilitation, and 11% in outpatient settings did not regularly use standardized tools to assess walking poststroke. Some therapists used modified versions of standardized assessment tools or created their own assessments. The standardized assessment tools used by 10 or more physical therapists were the Timed “Up & Go” Test (TUG),30 the CMSA,12 the Two-Minute Walk Test (2MWT),13 and the 6MWT.13

Many of the physical therapists interviewed also described valuing use of observational gait assessment in addition to or instead of administering standardized measures: “It's observational. For me, it's very observational.” (PT012, acute setting) While observing, therapists described evaluating gait pattern, foot placement, and control.

Knowledge About Walking Assessment Methods Is Derived From Formal Education, Physical Therapist Students, the Provincial Stroke Network, and Research

Nine physical therapists described learning about methods of assessing walking through their professional degree program, as well as through postgraduate courses: “I'm a fairly recent grad. I've only been out for 2½ years, so I guess I still rely a lot on what I learned in school.” (PT002, rehabilitation setting) Two participants also described learning about the newest standardized assessment tools for stroke care from physical therapist students they supervised during clinical internships: “I love taking students because I love when students teach me things. So I have a student right now, and I'm always asking, ‘What's new in the world of outcome measures?’…so I'm very influenced by that.” (PT023, rehabilitation setting)

Physical therapists most often learned about assessment methods through the Ontario Stroke Network and research. Eleven therapists described how the best practice leader or one of the coordinators within the Ontario Stroke Network informed them about methods to assess walking by disseminating information and organizing informal discussions, in-service programs, and training sessions. Eleven therapists also described learning about assessment methods through involvement in a research study and by reading the research literature. The work setting for some therapists was a site for a stroke guideline implementation trial called the Stroke Canada Optimization of Rehabilitation by Evidence–Implementation Trial (SCORE-IT), which led to use of the 6MWT in the current study, as this test was required for the trial. Reading published research about assessment methods also influenced use.

A Hierarchy of Factors Influences Choice of Walking Assessment Method

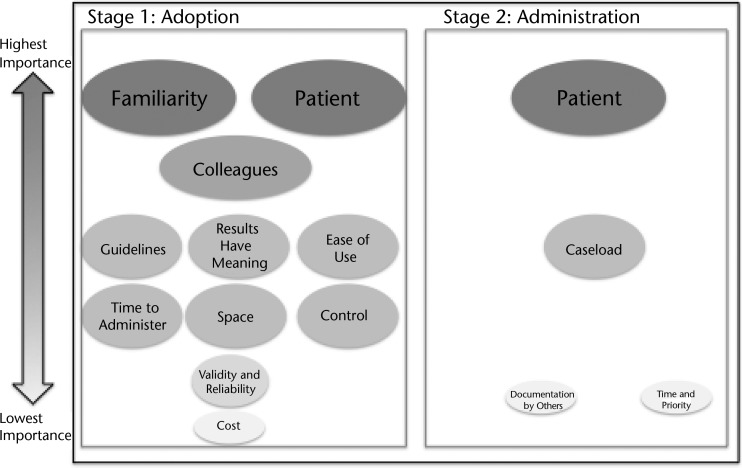

Participants discussed factors that influenced their decision to incorporate a measure into clinical practice represented by the term “adoption” in the Figure. They further discussed factors that determined if they were able to use a measure in daily practice represented by the term “administration” in the Figure. The level of importance was determined by how many physical therapists mentioned the factor and whether they described the factor as exerting the greatest influence. The size of the ovals and vertical placement in the Figure translate the importance of factors, wherein factors in the largest ovals at the top are most important and factors in the smallest ovals at the bottom are least important. The Figure presents influential factors, not methods of learning about a new assessment method.

Figure.

Factors influencing physical therapists' decisions to adopt and administer standardized measures of walking poststroke. This figure depicts 2 stages (adoption and administration) of decision making, as well as the hierarchy of importance of each factor. A physical therapist moves from stage 1 (adoption) to stage 2 (administration). Importance is indicated by vertical placement of a factor in the figure and the size of the oval. Importance of a factor increases from the bottom to the top of the figure and as the oval size increases.

Familiarity with a measure exerted the strongest influence on the decision to adopt that measure in clinical practice. The remaining factors influencing adoption, including colleagues, guidelines, results having meaning, ease of use, time to administer, space, control, validity and reliability, and cost, are less important than familiarity. Stage 2, the decision to administer a measure with each patient, is influenced first and foremost by patient factors, then caseload, time and priority, and documentation by others. From our perspective, patient factors appear in both stages, as physical therapists will not adopt a measure if they feel the assessment method is not appropriate for the patients they treat.

Familiarity.

After learning a new assessment, physical therapists across settings described a need to become personally familiar with it before they used it in clinical practice. When asked about the strongest influence on assessment choice, one therapist stated, “I would say, unfortunately, it falls back into old habits.” (PT015, acute setting) Skill and confidence to administer a method of walking assessment are components of familiarity and influenced use. Many therapists indicated that they were not comfortable using assessments that they had not learned in detail: “The tests that we really practiced in labs (at school) I'm much more comfortable with, and so I would choose them over a test that I learned more as a professional.” (PT002, rehabilitation setting)

Colleagues.

Physical therapists described how colleagues influenced the methods they used to assess walking poststroke. Recent graduates of physical therapist education programs described being influenced by more experienced or senior physical therapists: “Definitely, I work with some more senior therapists than me, so I do consider their input, and I think if they were using a certain one particularly, I would definitely lean towards doing that.” (PT008, acute setting)

Best practice guidelines.

The influence of best practice guidelines was discussed by physical therapists across all 3 settings. Two therapists in acute care thought walking measures recommended in the best practice guideline, specifically the 6MWT, were not appropriate for patients with acute stroke. Therapists in rehabilitation hospitals more often described how guidelines positively influenced their selection of assessment method than physical therapists practicing in acute care. In outpatient settings, some therapists felt influenced by guidelines, whereas others did not.

Ease of use of assessment, time assessment takes to administer, and results have meaning.

Physical therapists described how the characteristics of the measure itself (ie, ease of use, administration time, and meaning of results) affected their decision to administer it. They chose assessments based on how easy they were to use. Observational gait analysis, TUG, 2MWT, 6MWT, and gait speed tests were identified as being easy to complete, as these methods were easy to explain and simple for patients to understand.

The time to complete an assessment influenced the adoption of a measure across all care settings. For example, the 2MWT was used instead of the 6MWT because of the shorter testing time. The CMSA was noted as taking a long time to administer. Finally, physical therapists were more likely to use a measure if they perceived the test to be informative about multiple physical functions and provide prognostic value. For example:

The Timed Up & Go is very functionally relevant. You are looking at obviously walking speed, but you are looking at functional ability to sit-to-stand and turn, which are…indicative of functional ability in the community and fall risk. (PT005, outpatient setting)

Space and control.

Some therapists did not have adequate space to administer standardized assessment tools and felt that this lack of space limited what they could do: “I think we struggle here because we don't have an environment that's always conducive to gait assessment and working on gait.” (PT021, acute setting) The 2MWT and 6MWT were the standardized assessments most affected by lack of space.

Physical therapists also were limited in what they could do in their space. Two therapists indicated that, in their workplaces, leaving paint or tape on the floors to mark out an assessment distance was not allowed due to infection control. These therapists mentioned that measuring these distances each time was tedious and time-consuming.

Some physical therapists felt that their workplace controlled how walking was assessed by requiring physical therapists to use certain assessment tools, such as the FIM. It was mentioned that other walking assessments could be added, if needed.

Validity and reliability.

Some therapists described how evidence of validity and reliability influenced their adoption of an assessment tool: “I think that probably the most important thing in an assessment tool is that it has some…it's been shown to be valid. There is some validity, and there is also some literature telling me what degree of change is significant.” (PT003, outpatient setting)

Cost.

A few therapists mentioned that if specific equipment is required, it would have to be affordable, as there were limited funds. An example of expensive equipment mentioned was a computerized mat that was pressure sensitive to evaluate gait.

Patient factors.

Physical therapists found it easier to administer standardized measures of walking in patients with adequate postural control and balance and exercise tolerance. Some therapists described only using standardized tools to assess walking in patients who were independent ambulators and tended to prefer observational gait analysis in patients who needed a lot of physical assistance. Cognitive impairments also posed barriers to use of standardized assessment tools, as one therapist explained:

I have another gentleman right now who is walking with fairly minimal assistance. However, his cognition and language…they limit him in such a way that things have to be kept very, very functional and very, very concrete…the trouble I would have with him trying to do a standardized assessment is that he wouldn't necessarily understand the directions. He would need a lot of cueing throughout the entire process, and, once again, that invalidates your results. (PT025, acute setting)

Additional challenges across settings included language barriers, fatigue, visual neglect, and impaired proprioception.

Caseload.

The average number of patients seen per day varied with each physical therapist. Large patient caseloads did not allow therapists to administer all of the standardized assessment tools that they would like to administer.

Documentation by others.

Documented use of a measure by others, such as admission notes, helped therapists decide what standardized walking assessments to use to illustrate the progression made from previous settings. For example, 2 physical therapists used health records to determine what walking assessments were administered in acute care and would use the same assessment tool, provided it was in their repertoire.

Time and priority.

Some therapists reported having little time with patients and administering a standardized measure of walking ability was not a priority:

So, the first way is just for myself to decide on what's the most important thing to treat, so…if I only have 10 minutes to treat them or they are going home that day and I have to give them a home program with the most important exercise, what's it going to be? (PT015, acute setting)

Clinical Use of Walking Assessment Results Varies

Physical therapists most commonly described using results from walking assessments for communication with other health care professionals and the patient. Physical therapists reported communicating walking assessment results regarding patient safety within the facility and in the community to other health care professionals in rounds or multidisciplinary team meetings.

Education of the patient and family involved showing or describing change and progress in walking speed or function. Therapists described using this approach to encourage, build confidence in, and motivate the patient. A physical therapist who used the 2MWT and TUG stated, “I find the patients really want to know, and so it often gives them a lot of hope if I say, ‘Look, this is how you were when you came in, and now look how great you are doing.’” (PT002, rehabilitation setting)

Therapists also reported using assessment results to formulate a prognosis for walking recovery and to plan treatment and discharge. In acute care and outpatient settings, most therapists reported using the results of walking assessments to help focus their treatment approach. For example, therapists indicated that if they noticed an impairment in hip extension while observing a patient, that is where they would focus their treatment. In contrast, most physical therapists in rehabilitation felt that assessment results did not guide their treatment planning. More experienced therapists noted assessment results validated their treatment plans, whereas one therapist stated, “Earlier in my career, they would help direct the decisions I was going to make.” (PT014, rehabilitation setting) Most outpatient physical therapists described using assessment results to determine when to terminate care.

Many physical therapists used assessment results in planning discharge to a rehabilitation hospital or home. Some therapists used the results from both observational gait analysis and standardized assessment tools such as the TUG to help form recommendations for the type and duration of rehabilitation needed, as well as to determine whether a patient could be safely discharged to the community:

[I]n terms of the more quantitative Timed “Up & Go” Test, it's a matter of sort of…figuring out is this person going to be safe and…[is this person] close to being safe in the community? Should I send home care therapy in to address this? Should we be looking [at] more rehab so we can help with the decision in terms of discharge destination? (PT025, acute setting)

Results from standardized measures of gait speed were used to determine whether a patient would be able to cross the street in the time of a walk signal:

To integrate it to real life in the community setting. So, when we are going outside, and we are actually crossing streets…to be able to say, oh well, your gait speed may not be quick enough so you may have to…either rethink how you cross the street…different strategies to manage that in real life. (PT009, rehabilitation setting)

There Is Little Consensus on Ways to Assess Walking Across the Care Continuum

Physical therapists were asked to recommend methods for assessing walking across the care continuum. Some therapists were not comfortable suggesting specific standardized assessment tools. Others recommended the 6MWT, 2MWT, TUG, CMSA, 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT), and FIM.

Many physical therapists believed that the assessment tools should vary across the continuum to address the focus of therapy and change in ability:

[I]n the acute care setting, if it's a more heavily affected stroke patient, they often don't have the time to address walking if it is very complicated and takes assistance of 2 or 3 people to begin with. So, it's really hard to say across the continuum, and if you actually get a person to the point of the longer-stay rehab, their walking ability will be changing so much that you can then entertain using different outcome measures as they go, and certainly as an outpatient, they would be maybe even higher functioning and you can look at community walking types of assessments also. (PT028, rehabilitation setting)

Some therapists suggested the same methods or tools be used across at least 2 settings or the entire care continuum to enable tracking of ability and facilitate communication: “I'd just like an outcome measure to follow at least 2 continuums so that we speak the same language.” (PT023, rehabilitation setting) A few participants felt that observation, specifically examining gait patterning, was the best method of assessing walking ability across the continuum poststroke but that a standardized method is lacking: “I've never read anything that assisted me in assessing it. For me, it's always feeling the weight, seeing what's going on. That's how I do it.” (PT012, acute setting)

Discussion

The present study is the first to describe how physical therapists working in an organized system of stroke care assess walking across the care continuum. The 5 themes suggest that physical therapists use both standardized and nonstandardized methods to assess walking poststroke; they learn about methods through formal and informal experiences; the factors that influence their assessment practice vary in importance; they use the results from assessments mainly for education, communication, and treatment planning; and they have variable perceptions on how walking should be assessed across the care continuum. Findings from across the themes can inform the design of interventions to encourage the adoption and consistent administration of standardized measures of walking.

Physical therapists in this study identified observation of walking as a valuable assessment method, and, for some, it was the only method. Those in acute care were the least likely to use standardized assessment tools due to the short length of hospital stay and high level of patient disability. Lack of time has been cited as a barrier to the use of standardized assessment tools in multiple studies,19,21,23,24 and average patient length of stay in acute care in Ontario, Canada, in 2010 to 2011 was 8.5 days.31 Many patients are unable to walk without physical assistance immediately poststroke and require time to recover before assessment tools requiring independent ambulation can be administered.2

This study described variability in the source of physical therapists' knowledge of assessment methods. Physical therapists seemed to prefer learning about a new standardized assessment tool in ways that allowed them to have hands-on experience, such as in the laboratory sessions during their professional education or in hands-on postgraduate courses. The ability to practice using the standardized assessment tool increased their confidence and familiarity with the tool, which exerted the strongest influence on the decision to adopt a measure. A preference for hands-on learning has been reported in a previous qualitative study of physical therapists providing services poststroke in Ontario.32 These findings indicate that interventions aimed at changing physical therapists' assessment practice should focus on providing sufficient opportunities to practice.32 Results from the current study reinforce previous reports that physical therapists learn about new assessment methods when they supervise physical therapist students.32

Surprisingly, the influence of the Ontario Stroke Network was not universal. Eleven physical therapists did mention learning about methods to assess walking through the network, which suggests the potential for the network to influence practice. The varying influence of the network could reflect different priorities for knowledge translation across regions.

Physical therapists' descriptions of using the results from the walking assessments for prognosis of walking recovery, treatment planning, monitoring change, communication with other health care professionals on patient status, education of patients regarding their progress, and discharge planning align with previous findings.33,34 The results from this study did not indicate that physical therapists use results of standardized assessment tools of walking to provide a baseline status of magnitude of deficit. Participants described a preference for observational gait analysis for the detection of deviations in gait pattern that they would presumably treat. There was no discussion about the relationship between assessment and the use of interventions with known efficacy to improve walking, despite evidence that, for example, people who walk between 0.3 and 0.7 m/s benefit most from task-oriented walking training poststroke.35 These findings indicate that greater efforts are needed to link assessment findings to treatment prescription poststroke.

Physical therapists' opinions on what assessments to use across the continuum varied. What is likely more beneficial than practice setting–specific tools are patient ability–specific tools discussed in the next section.

Recommendations

Four recommendations to guide future research and practice can be formulated based on findings from the current study. First, consensus as to which standardized assessment tools are most appropriate to apply clinically for people with mild, moderate, and severe walking deficits poststroke is necessary. The need for physical assistance to walk emerged as a primary influence on the decision to use standardized measures of walking, indicating that ambulatory level more than clinical setting should drive recommendations for an optimal set of walking assessment tools. According to participants, the advantages of consistently using specific measures in patients of the same ambulatory level across settings were streamlining of reporting and optimizing communication with health care professionals, patients, and families.

The American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section Task Force recently used a consensus process to develop recommendations for use of standardized assessment tools poststroke in clinical practice, education, and research.36 Out of 56 assessment tools fully reviewed, the group highly recommended the 6MWT,13 the 10MWT,37 and the Dynamic Gait Index38 on the basis of psychometric evidence and clinical utility to clinically evaluate walking across all settings (acute, rehabilitation, outpatient, and skilled nursing facilities) and levels of patient acuity (acute, subacute, and chronic stroke). The 6MWT and 10MWT are 2 of the tests that physical therapists in the current study suggested to use across the care continuum. Thus, a second recommendation is that the 6MWT and 10MWT should be considered as primary candidates for the evaluation of individuals poststroke who are able to walk independently, with or without assistive devices, across clinical settings.

A third recommendation is that research is needed to develop and validate procedures for administering measures of walking and other rehabilitation outcomes in patients with stroke-related cognitive impairment and aphasia. This recommendation incorporates findings from the “administration” stage described in the Figure. People with these deficits may be unable to focus on and understand multistep instructions and may become distracted during testing, resulting in an inaccurate performance score. A reliable test protocol that addresses these issues would inform clinical guidelines on how to proceed when cognitive and communication deficits are present.

A fourth recommendation is that factors influencing the “adoption” of an assessment tool, as described in stage 1 in the Figure, should be considered in the development of knowledge translation interventions to facilitate the uptake of specific assessment tools. For example, these interventions should highlight the psychometric evidence supporting the tool; enlist the help of influential experienced therapists to champion the practice; and incorporate the need to practice administering the tests and information on interpreting and using scores for treatment planning, goal setting, and formulating a prognosis to optimize clinical utility. Suggestions for addressing barriers to standardized assessment, such as inability to mark the floor due to infection control measures, also should be provided. A similar approach targeting physical therapist student interns within academic programs may help reinforce adoption of assessment practices in the clinical setting. The effectiveness of this type of active approach is supported by the knowledge translation literature.39

Limitations

This study had a number of limitations. The method of sampling through recruitment notices may have attracted physical therapists who regularly use standardized assessment tools for walking poststroke more than those who do not. Selected results may not be generalizable to countries or regions that do not have an organized approach to health care poststroke. Also, interviewing over the telephone prevents observation of any nonverbal responses, such as facial expressions or body language, that can indicate comfort level and emotional responses of participants. For the pragmatic subject matter of this study, however, results obtained from telephone and face-to-face interviews are expected to be similar.40

By providing information on how physical therapists learn assessment practices, and how they are influenced to adopt and implement new assessment methods on an daily basis, study findings can be used to inform future research on the development of standardized assessment tools and of knowledge translation resources and education interventions designed to foster use of standardized walking assessment practices across the care continuum poststroke.

Appendix.

Appendix.

Interview Guide

Footnotes

All authors provided concept/idea/research design, writing, and data analysis. Ms Pattison and Dr Salbach provided data collection. Ms Pattison provided project management. Dr Salbach provided fund procurement, facilities/equipment, and institutional liaisons. Dr Brooks, Dr Cameron, and Dr Salbach provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

The Research Ethics Board at the University of Toronto approved the study protocol.

This project was funded by a Connaught New Researcher Award, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto. Dr Brooks holds a Canada Research Chair. Dr Cameron and Dr Salbach hold Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation Early Researcher and Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Awards.

References

- 1. The Internet Stroke Center. Stroke statistics. 2013. Available at: http://www.strokecenter.org/patients/about-stroke/stroke-statistics/ Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 2. Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Michael KM, Allen JK, Macko RF. Reduced ambulatory activity after stroke: the role of balance, gait, and cardiovascular fitness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1552–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinée S, Côté R, et al. Activity, participation, and quality of life 6 months poststroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elsworth C, Dawes H, Sackley C, et al. A study of perceived facilitators to physical activity. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2009;16:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee CD, Folsom AR, Blair SN. Physical activity and stroke risk: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2003;34:2475–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bohannon RW, Andrews AW, Smith MB. Rehabilitation goals of patients with hemiplegia. Int J Rehabil Res. 1988;11:181. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care. Initial stroke rehabilitation assessment. 2013. Available at: http://www.strokebestpractices.ca/index.php/stroke-rehabilitation/initial-stroke-rehabilitation-assessment/ Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 9. Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care. Lower limb gait following stroke. 2015. Available at: http://www.strokebestpractices.ca/index.php/stroke-rehabilitation/providing-stroke-rehabilitation-to-maximize-participation-in-usual-life-roles-lower-limb-and-gait/lower-limb-gait-training-following-stroke/ Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 10. Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS. The Functional Independence Measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil. 1987;1:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The AlphaFIM Instrument Guide. Buffalo, NY: Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gowland C, Stratford P, Ward M, et al. Measuring physical impairment and disability with the Chedoke-McMaster Stroke Assessment. Stroke. 1993;24:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, et al. Two-, six, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;284:1607–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Peppen RPS, Hendriks HJM, van Meeteren NLU, et al. The development of a clinical practice stroke guideline for physiotherapists in the Netherlands: a systematic review of available evidence. Disabil Rehabil. 2007:29:767–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Management of stroke rehabilitation. 2010. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/stroke/stroke_full_221.pdf Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 16. Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National Clinical Guideline for Stroke. 4th ed London, United Kingdom: Royal College of Physicians; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke management. 2010. Available at: https://strokefoundation.com.au/∼/media/strokewebsite/resources/treatment/clinical-guidelines-acute-rehab-management-2010-interactive.ashx?la=en/ Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 18. Beattie P. Measurement of health outcomes in the clinical setting: applications to physiotherapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2001;17:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salbach NM, Guilcher SJT, Jaglal SB. Physical therapists' perceptions and use of standardized assessments of walking ability post-stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lennon S. Physiotherapy practice in stroke rehabilitation: a survey. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Copeland JM, Taylor WJ, Dean SG. Factors influencing the use of outcome measures for patients with low back pain: a survey of New Zealand physical therapists. Phys Ther. 2008;88:1492–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Peppen RPS, Maissan FJF, Van Genderen FR, et al. Outcome measures in physiotherapy management of patient with stroke: a survey into self-reported use, and barriers to and facilitators for use. Physiother Res Int. 2008;13:255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maher C, Williams M. Factors influencing the use of outcome measure in physiotherapy management of lung transplant patients in Australia and New Zealand. Physiother Theory Pract. 2005;21:201–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swinkles RAHM, van Peppen RPS, Wittink H, et al. Current use and barriers and facilitators for implementation of standardized measures in physical therapy in the Netherlands. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McGlynn M, Cott CA. Weighing the evidence: clinical decision making in neurological physical therapy. Physiother Can. 2007;59:241. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ontario Stroke Network. Our history. 2010. Available at: http://ontariostrokenetwork.ca/about-the-osn/the-history-of-osn/ Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 27. Central East Stroke Network. Overview of the CESN. 2014. Available at: http://www.cesnstroke.ca/about-us/about-the-cesn/ Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 28. Ontario Stroke Network. OSN management team. 2013. Available at: http://www.ontariostrokenetwork.ca/about-the-osn/osn-management-team/ Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 29. Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basicfunctional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hall R, Khan F, O'Callaghan C, et al. Ontario stroke evaluation report 2012: prescribing system solutions to improve stroke outcomes. 2012. Available at: http://www.ices.on.ca/∼/media/Files/Atlases-Reports/2012/Ontario-stroke-evaluation-report/Full%20Report.ashx Accessed May 20, 2015.

- 32. Salbach NM, Veinot P, Jaglal S, et al. From continuing education to personal digital assistants: what do physical therapists need to support evidence-based practice in stroke management? J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;17:786–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chesson R, Macleod M, Massie S. Outcome measures used in therapy departments in Scotland. Physiotherapy. 1996;82:673–679. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bruton A, Conway JH, Holgate ST. Reliability: what is it, and how is it measured? Physiotherapy. 2000;86:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salbach NM, Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinée S, et al. A task-orientated intervention enhances walking distance and speed in the first year post stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18:509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sullivan JE, Crowner BE, Kluding PM, et al. Outcome measures for individuals with stroke: process and recommendations from the American Physical Therapy Association Neurology Section Task Force. Phys Ther. 2013;93:1383–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wade DT. Measurements in Neurological Rehabilitation. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott M. Motor Control: Theory and Applications. Baltimore, MD: Wilkins & Wilkins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, et al. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol. 2004;57:660. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sturges JE. Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: a research note. Qual Res. 2004;4:107–118. [Google Scholar]