Abstract

Objective

Impairments associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and noncompliance are prevalent in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, ADHD response to stimulants is well below rates in typically developing children, with frequent side effects. Group studies of treatments for noncompliance are rare in ASD. We examined individual and combined-effectiveness of atomoxetine (ATX) and parent training (PT) for ADHD symptoms and noncompliance.

Method

In a 3-site, 10-week, double-blind, 2×2 trial of ATX and PT, 128 children (ages 5–14) with ASD and ADHD symptoms were randomized to ATX, ATX+PT, placebo+PT, or placebo. ATX was adjusted to optimal dose (capped at 1.8 mg/kg/day) over 6 weeks and maintained for 4 additional weeks. Nine PT sessions were provided. Primary outcome measures were the parent-rated DSM ADHD symptoms on the Swanson, Nolan and Pelham (SNAP) scale and Home Situations Questionnaire (HSQ).

Results

On the SNAP, ATX, ATX+PT and placebo+PT were each superior to placebo (effect sizes 0.57–0.98), with p-values of 0.0005, 0.0004 and 0.025, respectively. For noncompliance, ATX and ATX+PT were superior to placebo (effect sizes 0.47–0.64; p values of .03 and .0028, respectively). ATX was associated with decreased appetite but otherwise well-tolerated.

Conclusion

Both ATX and PT resulted in significant improvement on ADHD symptoms while ATX (both alone and combined with PT) was associated with significant decreases on measures of noncompliance. ATX appears to have a better side effects profile than psychostimulants in the population with ASD.

Keywords: Atomoxetine, parent training, ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

One of the most common and impairing comorbidities in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is often accompanied by noncompliance, oppositional behavior, and irritability. ADHD occurs in about one-third of children with ASD1,2 and is associated with diminished quality of life and adaptive functioning.3 Noncompliance (e.g., ignoring, refusing, defying, or arguing with requests) occurs in approximately one in five children with ASD4,5 and can be highly stressful for children and families.6

Between 14% and 22% of children with ASD are being treated at any one time for ADHD symptoms, often with stimulant medication.7,8 However, response rates, defined as ≥25% symptom reduction plus clinician impression of improvement, are much lower in children with ASD than in typically developing (TD) children with ADHD.9 Approximately half of children with ASD are “responders,” demonstrating reduction in ADHD symptom burden, compared to 70% of TD children, rising to 90% if several stimulants are tried.10,11 Moreover, the rate of intolerable side effects is about four times higher in youth with ASD when compared with TD youth. 9,12 As a result, it is clear that non-stimulant medication interventions, as well as non-medication treatments to target ADHD symptoms, are needed for children with ASD.

Atomoxetine (ATX) has been shown to be effective for treating ADHD in the TD population. This non-stimulant agent is a potent inhibitor of the presynaptic norepinephrine transporter in the frontal cortex, and it has minimal affinity for other noradrenergic receptors.13,14 Across 25 pooled, randomized clinical trials (RCTs), the mean effect size for overall ADHD symptoms was 0.64, with a 60% response rate.15 The effect size for symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), however, was only 0 .33, suggesting that other treatment options may need to be included with ATX to address such symptoms.

A recent review of ATX in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities (DD) identified 11 studies, ten of which were conducted in patients with ASD.16 Only two were RCTs, with sample sizes of 16 and 97 and response rates of 57% and 21% respectively (versus 25% and 9% placebo response rates).17,18 Generally, across the 11 identified studies, rates of both inattention and hyperactivity were reduced, whereas oppositional behavior was lowered in about half of the comparisons. Decreased appetite, nausea, and irritability were the most common adverse events (AEs). With only two RCTs, the overall strength of evidence for a therapeutic effect of ATX in ASD and DD was low. As with stimulants, irritability appeared to be a more common side effect than was reported in TD children, indicating the need to be clinically vigilant for irritability effects when prescribing ATX for children with ASD or DD.

One possible means of increasing the number of ATX responders and the ES is to combine ATX treatment with a psychosocial intervention, such as parent training (PT). PT is well-established as an intervention for reducing noncompliant behaviors in a wide range of children and as an adjunct to medication in ADHD treatment.19,20 It also has support from many small-sample studies in the ASD literature21 and in one large RCT when combined with risperidone.22 However, few data are available on the efficacy of PT as a stand-alone treatment for noncompliance in ASD.23

An RCT of PT and risperidone together indicated that combined treatment was more effective than pharmacotherapy alone for reducing irritability in children with ASD.22 However, the additive value of PT was manifested only after 20 weeks. In addition to the behavioral benefits, individuals receiving combination treatment were prescribed statistically significant lower risperidone doses. The Multisite Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) similarly concluded that adding psychosocial treatment to medication (mainly methylphenidate) increased therapeutic benefit for managing ADHD symptoms and noncompliance while affording significantly lower medication dosing.24 In the present study, we looked at the single and combined effects of ATX and PT. We compared ATX versus placebo, and PT versus no psychosocial intervention in a 2-by-2 factorial design. We predicted that ATX and PT by themselves would each reduce ADHD symptoms and noncompliance, and that combined treatment would surpass unimodal treatment.

METHOD

We have previously described the background, methodological decisions, and feasibility of this study.25 The study was approved by the institutional review boards at all sites; parents/legal guardians signed informed consent, and children assented if able.

Sample Characteristics

Participants were between 5.0 and 14.11 years old, both male and female, with a minimum mental age (MA) of 24 months (based upon either the Stanford-Binet 5th Edition26 or Mullen Scales of Early Learning27). All participants met criteria for an ASD (autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified [PDD-NOS]), based upon the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised28 and expert clinical evaluation using a DSM-IV-TR interview.29 Participants also exhibited significant symptoms of overactivity and/or inattention at both home and school, based upon a mean item score ≥ 1.50 on the parent- and teacher-completed Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) scales30 and a Clinical Global Improvement (CGI) -Severity score ≥4.31 We originally excluded children with inattention only, but with prior approval from our Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), we changed our eligibility criteria to accept such children in order to increase enrollment. Participants were enrolled irrespective of severity of noncompliance scores. Consequently, some participants had no significant clinical noncompliance issues. Participants were free of psychotropic medications (with the exception of those on stable doses of melatonin or low-dose clonidine [≤0.3 mg/day] for sleep) for two weeks prior to study randomization. A single anticonvulsant for seizure control was allowed, provided that stable doses and seizure-free status had been six months or more. Exclusion criteria included Rett’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia, other psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, or current diagnosis of major depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Children with significant medical conditions (e.g., heart, liver, renal, or pulmonary disease) or significant abnormalities on routine laboratory tests and electrocardiogram (ECG) were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included a prior adequate trial of ATX (minimum of four weeks, with at least one week at ≥ 1.0 mg/kg) within the last two years, and regular usage of beta adrenergic blocking agents, asthma medicine, such as albuterol (because of potential for drug interaction), and prior involvement in a highly structured parent training program.

Design

This was a randomized, parallel-groups trial conducted at three sites (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, The Ohio State University, and University of Rochester). Randomization was stratified by site in equal numbers to ATX, ATX+PT, placebo+PT, or placebo and balanced by mental age (MA, < 6 years vs. ≥ 6 years) to ensure proportionate distribution of children with lower MA across the four groups. The study biostatistician generated the randomization sequence using a computer algorithm; a designated team member at each site (e.g., research pharmacist) obtained the assignment for each participant via a web portal maintained by the data center. ATX assignment was double-blind and PT assignment was rater-single-blind (i.e., only the family, behavior therapist, and study coordinator were aware of assignment to PT, while other study personnel remained blinded). School staff were aware that children were enrolled in the study (as teachers were asked to complete study questionnaires) but were not specifically told which families were assigned to PT (although it is possible that some parents informed their children’s teachers, especially if a school daily report card was implemented as part of the PT intervention). Study medical providers adjusted medication and monitored side effects. Families assigned to PT met with a behavior therapist who had been trained to use the PT manual with fidelity. Independent evaluators blinded to treatment assignment until completion of the study rated participants on the CGI scale.

Procedure

After completing the informed consent process, participants underwent an ASD diagnostic assessment and cognitive assessment. Both parents and teachers completed behavior rating scales to confirm the presence of ADHD symptoms and assess levels of noncompliance. Once study eligibility was established, participants were randomized to one of the four treatment arms. Study visits occurred weekly to assess medication response, monitor adverse events (AEs), and adjust doses. Individualized dose adjustments (maintaining or lowering) were allowed based on response, interval concerns, or AEs. Final dose adjustments were made at Week 6, with subsequent monitoring visits at Weeks 8 and 10. Families assigned to PT met weekly for 1:1 sessions with a PT clinician for 60 to 90 minutes.

At Week 10, patients were rated as ADHD responders based upon a CGI-Improvement rating of “1” or “2” for ADHD symptoms by the blinded evaluator and a ≥30% decrease on the Parent SNAP-IV. At the same time, patients were rated as noncompliance responders based upon a CGI-Improvement rating of “1” or “2” for noncompliance by the blinded evaluator and a ≥30% decrease on the HSQ.25 Responders (either ADHD or noncompliance) remained in their assigned treatments and continued in a double-blind 24-week extension (results to be reported elsewhere). Nonresponders had their medication blinding broken at the Week 10 visit and also entered the 24-week extension. Those who had received placebo during the first 10 weeks began an open trial of ATX, whereas those who had taken ATX during the first 10 weeks were treated clinically.25 Based on the finding in our previous trial that effects of PT emerged only at 16–24 weeks, we followed both responders and non-responders in the extension.22

Outcome Measures

The Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI):31

This scale includes subscales for severity of illness and global improvement. The Severity scale is scored from “1” (normal) to “7” (extremely ill), with a rating greater than 4 required for inclusion. The Improvement score ranged from “1” (very much improved) through “4” (no change) to “7” (very much worse). The CGI was completed by a blinded rater based on parent/child interview and review of completed parent and school behavior problem questionnaires at each study visit. Separate CGI ratings were obtained for ADHD and Noncompliance. This was done because we hypothesized that PT would have a greater impact on Noncompliance while ATX would have a greater impact on ADHD. Using a single global CGI-I rating would have made it difficult to discriminate between the impact of the two treatments.

The Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP)-IV:30

The SNAP-IV Parent and Teacher Rating Scales were used to measure ADHD and oppositional symptoms at home and school. The SNAP-IV, ADHD, and ODD sections include the 18 DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD (9 inattention and 9 hyperactive/impulsive items) and 8 symptoms of ODD rated on a 0–3 scale. A mean item score of ≥1.5 on the parent and teacher SNAP-IV18 ADHD symptoms or the 9-symptom hyperactive-impulsive items or the 9-symptom inattentive items served as a study inclusion criterion. Patients were not required to have elevated ratings on the ODD subscale (or on other measures of noncompliance) for study entry.

Home and School Situations Questionnaires (HSQ and SSQ):32,33

The HSQ and SSQ were completed by parents and teachers, respectively, to assess noncompliance. Originally developed to assess noncompliance in TD children with disruptive behavior,34,35 the 25-item HSQ was adapted by the Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network to evaluate behavioral noncompliance in children with ASD.33 The 9-item SSQ was used as originally designed. Items on both instruments are rated on 10-point Likert scales, ranging from 0–9.

Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC):36

The ABC is a 58-item behavior checklist completed by both parents and teachers. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (from “not a problem” to “severe in degree”). Five subscales are derived: I) Irritability (15 items), II) Social Withdrawal (16 items), III) Stereotypic Behavior (7 items), V) Hyperactivity/Noncompliance (16 items), and V) Inappropriate Speech (4 items). The ABC is reliable, valid, and sensitive to treatment effects (MG Aman, Annotated Bibliography on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC), unpublished manuscript, updated July 2012).37

The parent SNAP-IV and HSQ were completed at each study visit. The parent-completed ABC was completed on alternating weeks. The teacher SNAP-IV, SSQ, and ABC were completed every other study visit.

Adverse Events (AEs)

Study medical providers interviewed parents regarding AEs at each study visit, rating each as mild, moderate, or severe, after reviewing the parent-report side effect form, which was completed at every visit.

PT and Fidelity Procedures

Families assigned to PT met weekly for individual sessions with a PT clinician. Sessions were adapted from the RUPP Parent Training Manual and covered topics such as preventing behavior problems, reinforcement, time out, and planned ignoring.23 Each session lasted 60–90 minutes and included didactic materials, videos, and role playing.25 Parents were given weekly homework assignments and kept data on target behaviors. A home visit was also conducted between the second and third session. PT clinicians were trained by supervisors who were licensed clinical psychologists with specialized training in behavioral interventions and developmental disabilities (B.H. or T.S.). Prior to the start of the study, PT clinicians were certified by supervisors based on 85% or greater fidelity scores for implementation and scoring of manualized sessions with pilot families. Regular telephone conferences were held between site PT clinicians and supervisors to achieve standardization and to provide feedback from randomly viewed tapes.25 PT clinicians rated all sessions for their own fidelity to the manual; 15% of session videos (randomly selected) were also rated independently by B.H. or T.S.

ATX Dosage and Compliance

ATX doses were split twice daily to prevent side effects. However, once-daily dosing was allowed if strongly preferred by a given family. ATX doses were individually adjusted according to a weight-based dosage schedule, with medical clinicians allowed to delay increases or to reduce doses due to AEs. The initial dose was 0.3mg/kg/day (rounded to the nearest 5 mg) with weekly escalations by 0.3mg/kg/day, unless there were limiting side effects or no further room for improvement, to a target dose of 1.2 mg/kg/day, and could be increased to a maximum of 1.8 mg/kg/day based on clinical status and response.

Medication compliance was assessed via a daily medication log kept by families and by counting the remaining doses from returned bottles of medication. Families who regularly missed doses were counseled by medical clinicians and study staff to improve the consistency of medication administration.

Statistical Procedures

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for all randomized patients were summarized and compared among the four treatment groups using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables with proper data transformation if needed. All data analyses were conducted with the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare treatment effects for each continuous (primary or secondary) outcome with site, treatment, time, and time-by-treatment interaction included as independent variables. The comparisons of the changes from baseline to week 10 among treatment groups were based on the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation method using the MIXED procedure in SAS. Model assumptions were assessed by examination of residuals. The mixed procedure uses the missing at random (MAR) assumption to address all missing data. Sensitivity analyses were carried out using last-observation-carry-forward (LOCF) to confirm the conclusions reached based on the mixed models. These analyses are not reported here unless the conclusions differ from the primary analysis. Response rates were estimated based on the last parent rating (SNAP-IV for ADHD and HSQ for noncompliance) and CGI-Improvement scores (same as LOCF) for each treatment group and compared using Chi-square tests. The primary comparison for the ADHD symptom difference (SNAP-IV) was between the ATX (ATX+PT, ATX) and no ATX (PT or placebo) treatment groups. The primary comparison for noncompliance (HSQ) was between the PT (ATX+PT, placebo+PT) and no PT (ATX or placebo) treatment groups. Secondary outcomes concerned ATX effects on noncompliance and PT effects on ADHD and all variables not specified in the primary analyses. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p<.05, two-tailed, for primary and secondary outcome measures, and at p< .10 for AEs. Effect sizes were calculated by Cohen’s d, with changes from baseline to week 10, using data from patients with complete cases (Cohen, 1990; 1992).38,39 All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Sample Size Calculation

Our pilot study of ATX at the Ohio State University (OSU) site obtained an effect size of .90 for ADHD symptoms (MG Aman, Annotated Bibliography on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC), unpublished manuscript, updated July 2012). However, to be conservative, we calculated our sample size based on what we considered a minimally significant effect size of .60, and we allowed for attrition up to 20%. With these parameters, a minimum of 62 patients per group (ATX or no ATX, PT or no PT) provided 80% power to detect differences between groups at a significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

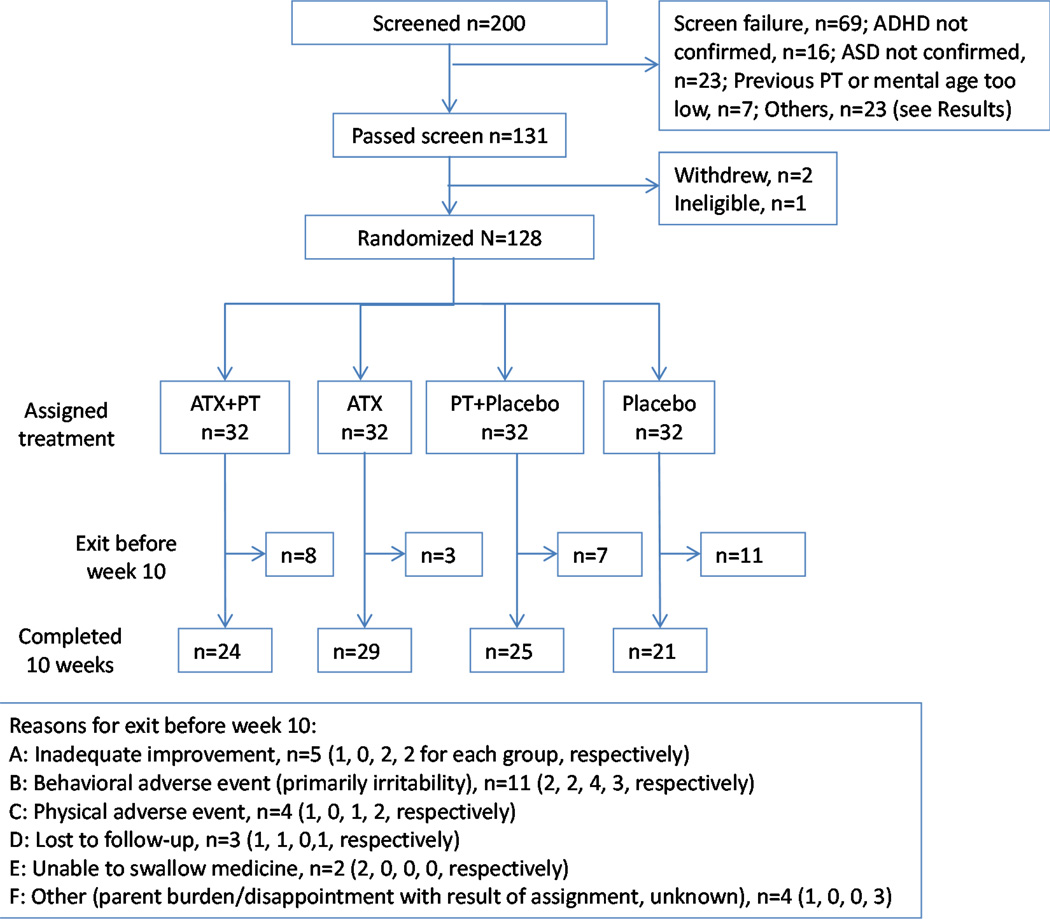

From January 2009 to April 2014 (when we met our enrollment target), 200 potential participants were screened, and 128 (64%) were randomized. Figure 1 depicts the Consolidated Standards of Reporting (CONSORT) diagram showing disposition of the entire sample, including randomized and “screened-but-not-randomized” participants. Sixty-nine individuals were ineligible. Sixteen of these did not meet entry criteria for ADHD; 23 did not have an ASD diagnosis; five had MA < 24 months; two parents had previous PT; and the remaining 23 did not qualify for other reasons (e.g., consent withdrawn, presence of other excluded psychiatric disorder, inability to complete washout, abnormal lab values, or use of excluded medications). In addition, two participants who passed the screening withdrew, and one child became ineligible due to ADHD severity declining at baseline. Table 1 summarizes participant demographics by group. The mean age for the entire sample was 8.1 (±2.1) years, and mean full-scale IQ was 81.7 (±24.3). Eighty-five percent of patients were boys. Eighty-two percent were Caucasian, 8% African American, 8% Multi-Racial, and 2% Other. One patient was on a stable anticonvulsant dose and 25 (19.5%) patients were taking melatonin for sleep (ATX+PT: 7; ATX: 8; PT+placebo: 6; placebo: 4). In addition, 58 (45.3%) patients had received prior treatment for ADHD; 49 of these patients had been treated with one or more stimulants, and 13 had been prescribed alpha-2 agonists or complementary and alternative treatments. One patient had a prior ATX trial that was considered to have been inadequate. The children’s type of school placement differed significantly between groups, but no other group differences were noted. The baseline CGI-S rating for both ADHD and Noncompliance was not statistically different across the four treatment groups.

Figure 1.

Consolidated standards of reporting (CONSORT) diagram. Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD = autism spectrum disorder; ATX = atomoxetine; PT = parent training.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics by Randomized Treatment Group

| Variable | ATX + PT n=32 |

ATX n=32 |

Placebo + PT n=32 |

Placebo n=32 |

p Value Comparing Groups |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (%) | 8.0 (1.9) | 8.6 (2.3) | 7.7 (1.5) | 8.2 (2.4) | .29 | |

| IQ, standard score (%) |

83.3 (21.6) | 78.7 (25.9) | 77.9 (25.7) | 86.7 (23.7) | .43 | |

| Autistic Disorder, % | 37.5 | 43.8 | 43.8 | 53.1 | .70 | |

| Asperger’s, % | 15.6 | 21.9 | 15.6 | 12.5 | .84 | |

| PDD-NOS, % | 46.9 | 34.4 | 40.6 | 34.3 | .73 | |

| Male, % | 96.9 | 81.3 | 84.4 | 78.1 | .13 | |

| Caucasian, % | 87.5 | 84.4 | 81.3 | 75.0 | .67 | |

| African Am, % | 3.1 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 15.6 | .39 | |

| Income ≥$60K (%) | 56.3 | 46.9 | 53.1 | 56.3 | .91 | |

| <$60K | 43.7 | 53.1 | 46.9 | 43.7 | ||

| Regular Ed, % | 43.7 | 28.1 | 46.9 | 65.6 | .028 | |

| Special Ed, % | 56.3 | 71.9 | 53.1 | 34.4 | ||

| ADHD CGI-S, n (%) | ||||||

| Moderate | 9 (28) | 9 (28) | 7 (22)a | 9 (28) | .44 | |

| Marked | 19 (59) | 15 (47) | 18 (58)a | 12 (38) | ||

| Severe/Extreme | 4 (13) | 8 (25) | 6 (19) | 11 (34) | ||

| Non-Compliance CGI-S, n (%) | ||||||

| Mild | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (3)a | 1 (3) | .90 | |

| Moderate | 19 (59) | 16 (50) | 17 (53)a | 15 (47) | ||

| Marked/Severe | 11 (35) | 15 (47) | 13 (41)a | 16 (50) | ||

Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ATX = atomoxetine; CGI-S = Clinical Global Impressions-Severity score; PDD-NOS = pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified; PT = parent training.

One participant’s data not obtained.

Exposure to Treatments and Treatment Fidelity

Ninety-nine children (77%) completed the 10-week trial. Figure 1 describes the reasons for study discontinuation for the remaining 29 children. The mean number of PT sessions attended was 7.0 for the ATX+PT group and 6.9 for the PT +placebo group (p= 0.82). Two independent raters (B.H. and T.S.) viewed 15% of PT session videos (randomly selected) to monitor PT treatment fidelity. An 80% or greater level of fidelity to the manual was established as the standard for a session to meet fidelity criteria. Of 61 sessions viewed, 54 (88.5%) were determined to meet the fidelity standard. Drug compliance was 95% for the ATX, PT+placebo and placebo groups and 91% for the ATX+PT group. Table 2 summarizes ATX dose (ATX or placebo) information by treatment group. Dose data are presented by mean final dose (both in mg and mg/kg) at Week 10. The ATX+PT group had the lowest prescribed dose (mg/kg), followed by ATX, placebo, and placebo+PT. However, none of the differences was statistically significant (p<0.59).

Table 2.

Group Exposure to Medication and Parent Training (PT)

| Treatment Condition |

Final Dose* (mg) |

Final Dose Per Weight ** (mg/kg) |

ATX vs. Placebo *** (mg) |

ATX vs. Placebo **** (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATX | 49.8 ± 23.3 | 1.38 ± 0.47 | 45.0 ± 21.5 | 1.37 ± .46 |

| ATX + PT | 40.0 ± 18.4 | 1.35 ± 0.45 | ||

| Placebo + PT | 42.4 ± 14.3 | 1.49 ± 0.36 | 44.0 ±17.5 | 1.46 ± 0.39 |

| Placebo | 45.6 ± 20.3 | 1.43 ± 0.43 |

Note: ATX = atomoxetine.

p=.21;

p=.59;

p=.76;

p=.22

Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures

Based on our a priori definition of ADHD responders (≥30% decrease on the SNAP and CGI-I≤2), the response rates were 45.2% for ATX+PT, 46.9% for ATX , 29.0% for PT+placebo, and 19.4% for placebo (ATX groups>placebo, p = 0.015 Fisher Exact Test). The rates of Noncompliance response (≥30% decrease on the HSQ and CGI-I≤2) were 22.6% for ATX+PT, 43.8% for ATX, 38.7% for PT+placebo, and 16.1% for placebo. No significant Noncompliance responder differences were found between the two PT treatments versus no-PT (p=0.95), or between the two ATX treatments versus placebo (p=0.47).

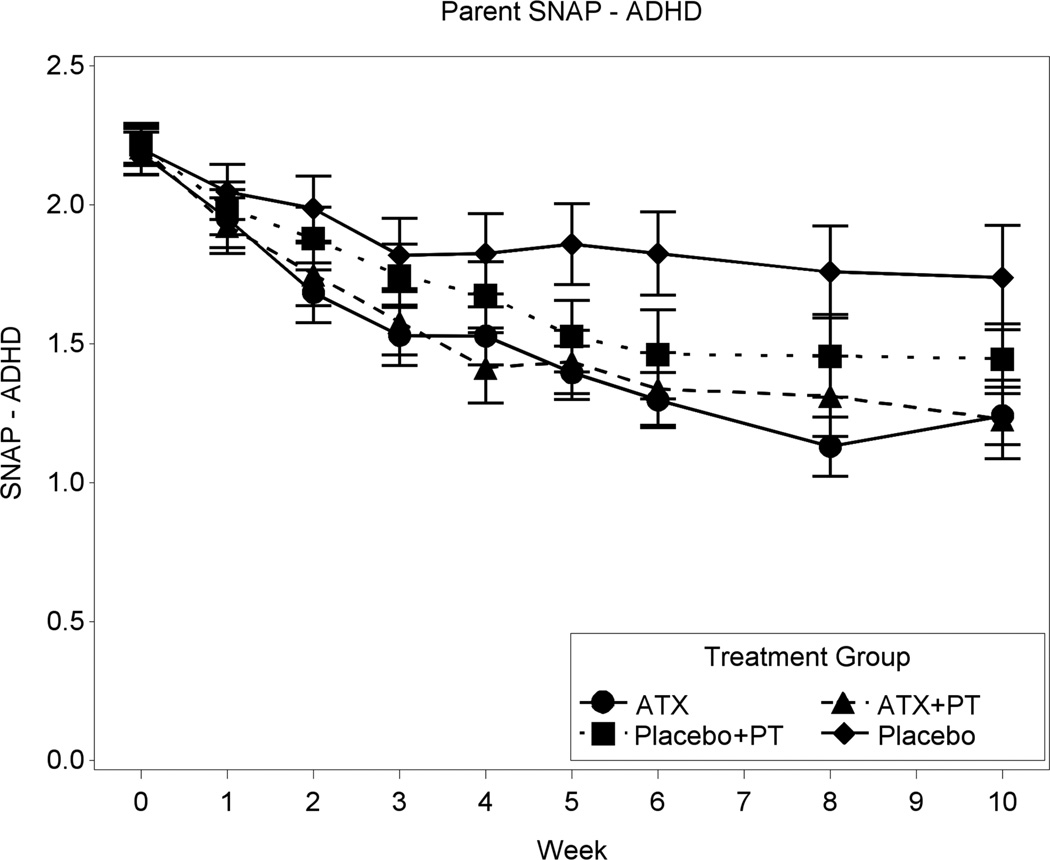

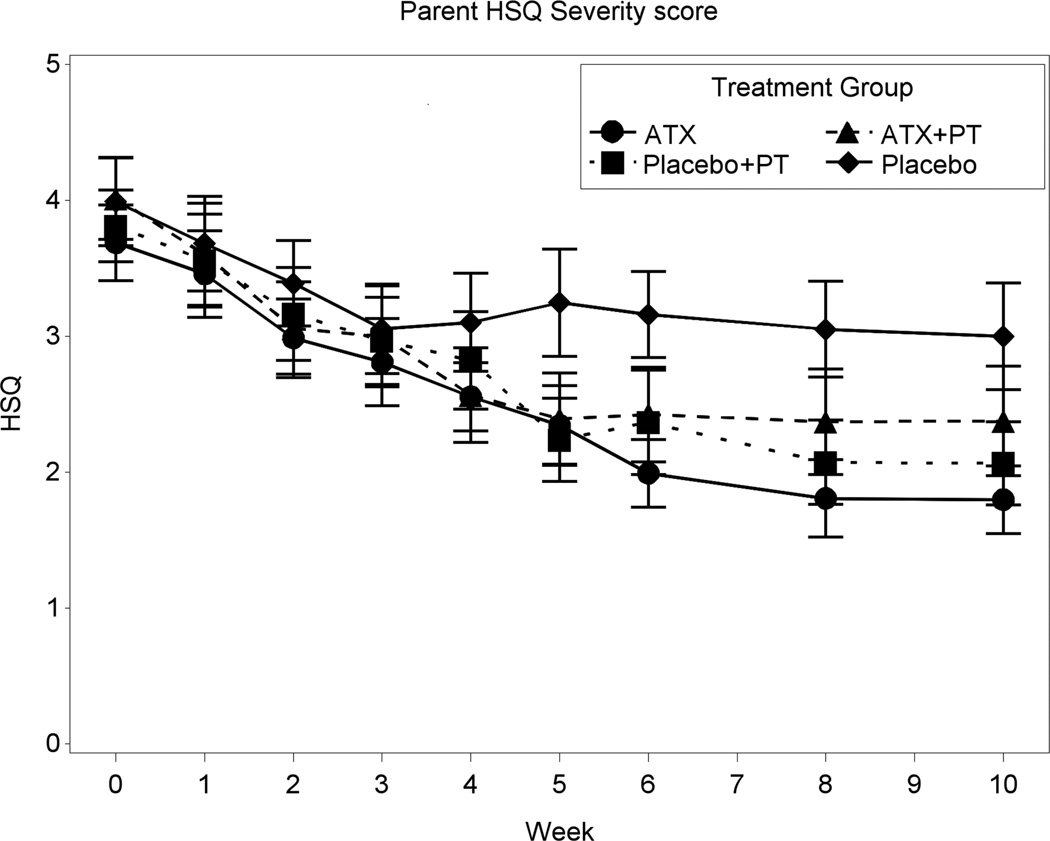

Figures 2 and 3 depict the summaries of the primary dimensional ADHD and Noncompliance outcome measures. After 10 weeks of treatment, the SNAP ADHD scores decreased 44.3% for ATX+ PT, 43.1% for ATX, 34.6% for PT+placebo, and 20.9% for placebo. The numeric findings (including least squares [LS] means, SDs, sources of significance, and effect sizes) for baseline and end-point are summarized in Table 3. Where significant treatment effects occurred, these are identified in the right-most column of Table 3. The Inattention, Hyperactivity, and ADHD Total on the parent-rated SNAP showed significant effects for all three active conditions relative to placebo alone. The effect sizes for ATX alone ranged from .68 to .84, whereas the effect sizes for PT+placebo ranged from .46 to .60. Based on the linear mixed model, the two ATX treatment groups had statistically significant greater improvement on the ADHD Total score than the two placebo groups (p=.0004). After 10 weeks of treatment, the HSQ score declined 40.6% for ATX+PT, 51.2% for ATX, 45.7% for PT+placebo, and 24.8% for placebo. The change on the HSQ was significant for ATX+PT versus placebo (effect size = 0.47, p=0.030) and for ATX versus placebo (effect size = 0.64, p=.0028), but not for PT+placebo versus placebo (p= 0.061). While the two ATX groups had statistically significant improvement compared to the two placebo groups (p=0.019), the HSQ improvement of the two PT groups was not statistically higher than the two no-PT groups (p=0.43).

Figure 2.

Parent Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) scales mean attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) score. Note: ATX = atomoxetine; PT = parent training.

Figure 3.

Parent Home Situations Questionnaire (HSQ) mean severity score. Note: ATX = atomoxetine; PT = parent training.

Table 3.

Least Squares Means and Standard Deviations for Primary and Secondary Variables at Baseline and Week 10

| Baseline | Week 10 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ATX+PT (1) |

ATX (2) |

Placebo+PT (3) |

Placebo (4) |

ATX+PT (1) |

ATX (2) |

Placebo+PT (3) |

Placebo (4) |

Source of Significance and ES |

| SNAP Parent | |||||||||

| ADHD | 2.21 (0.38) | 2.18 (0.44) | 2.22 (0.37) | 2.20 (0.52) | 1.23 (0.69) | 1.24 (0.56) | 1.45 (0.62) | 1.74 (0.86) | 1:4***,a 2:4***,b 3:4*,c |

| Inattention | 2.28 (0.46) | 2.30 (0.43) | 2.23 (0.49) | 2.27 (0.51) | 1.30 (0.72) | 1.36 (0.61) | 1.45 (0.71) | 1.79 (0.84) | 1:4***,d 2:4***,e 3:4*,f |

| HA | 2.14 (0.48) | 2.07 (0.65) | 2.20 (0.48) | 2.13 (0.69) | 1.15 (0.74) | 1.12 (0.65) | 1.44 (0.72) | 1.69 (0.97) | 1:4**,g 2:4***,h 3:4*,i |

| ODD | 1.33 (0.74) | 1.31 (0.65) | 1.37 (0.64) | 1.28 (0.82) | 0.96 (0.68) | 0.78 (0.52) | 0.70 (0.55) | 0.79 (0.50) | |

| SNAP Teacher | |||||||||

| ADHD | 1.99 (0.46) | 2.00 (0.53) | 1.98 (0.52) | 1.96 (0.59) | 1.14 (0.82) | 1.49 (0.74) | 1.46 (0.82) | 1.44 (0.85) | |

| Inattention | 2.13 (0.52) | 2.15 (0.54) | 2.16 (0.46) | 2.28 (0.49) | 1.30 (0.85) | 1.66 (0.78) | 1.64 (0.82) | 1.63 (0.98) | |

| HA | 1.86 (0.68) | 1.85 (0.72) | 1.81 (0.79) | 1.64 (0.90) | 0.98 (0.92) | 1.32 (0.92) | 1.28 (0.99) | 1.25 (0.92) | |

| ODD | 1.07 (0.73) | 1.21 (0.62) | 1.03 (0.76) | 1.04 (0.71) | 0.71 (0.65) | 0.87 (0.77) | 0.56 (0.66) | 0.83 (0.84) | |

| HSQ | |||||||||

| Severity | 4.01 (1.70) | 3.69 (1.58) | 3.81 (1.49) | 3.99 (1.82) | 2.38 (1.97) | 1.80 (1.34) | 2.07 (1.52) | 3.00 (1.79) | 1:4*,j 2:4**,k |

| SSQ | |||||||||

| Severity | 3.67 (2.08) | 3.40 (1.93) | 3.23 (1.93) | 3.75 (2.29) | 2.41 (2.26) | 3.06 (1.78) | 1.60 (1.43) | 3.04 (2.60) | 3:4*,l |

| ABC Parent | |||||||||

| Irritability | 17.88 (9.25) | 16.00 (9.74) | 18.16 (9.24) | 16.97 (8.36) | 11.71 (8.96) | 10.31 (7.87) | 9.92 (7.94) | 12.95 (7.43) | 3:4*,m |

| Social withdrawal | 12.09 (7.68) | 12.53 (9.22) | 8.56 (5.69) | 12.09 (7.12) | 7.46 (7.55) | 7.57 (7.80) | 3.64 (4.18) | 6.57 (4.46) | |

| Stereotypic behavior | 5.81 (4.69) | 7.41 (5.50) | 5.34 (5.03) | 5.06 (5.20) | 2.21 (2.48) | 4.55 (5.16) | 2.76 (2.73) | 3.52 (4.45) | |

| HA/NC | 29.94 (8.74) | 29.34 (9.52) | 31.31 (8.96) | 31.22 (10.11) | 16.92 (11.17) | 15.55 (9.77) | 20.24 (11.16) | 24.24 (13.78) | 1:4**,n 2:4**,o |

| Inappropriate speech | 5.56 (3.17) | 5.53 (3.44) | 5.72 (2.70) | 5.69 (3.75) | 3.58 (2.93) | 3.93 (3.51) | 3.92 (2.33) | 5.24 (4.15) | 1:4*,p 3:4*,q |

| ABC Teacher | |||||||||

| Irritability | 13.03 (10.85) | 12.96 (8.53) | 12.13 (9.62) | 14.71 (9.86) | 7.65 (7.74) | 8.97 (6.92) | 6.27 (7.40) | 12.60 (13.06) | |

| Social withdrawal | 12.10 (9.92) | 11.23 (7.58) | 9.65 (8.03) | 11.06 (7.48) | 7.59 (6.61) | 10.54 (7.63) | 7.93 (8.14) | 8.67 (10.40) | |

| Stereotypic behavior | 6.27 (5.21) | 6.84 (5.69) | 5.87 (4.19) | 6.35 (5.41) | 4.24 (5.84) | 5.00 (5.30) | 5.20 (5.48) | 5.40 (6.29) | |

| HA/NC | 24.37 (11.00) | 25.58 (10.08) | 24.29 (11.58) | 25.55 (12.99) | 13.88 (11.13) | 20.64 (12.52) | 19.00 (12.84) | 20.67 (14.18) | |

| Inappropriate speech | 3.97 (3.59) | 4.42 (3.91) | 3.55 (2.96) | 4.71 (3.43) | 2.76 (2.97) | 3.89 (3.38) | 4.13 (3.38) | 4.13 (3.98) | 3:4*,r |

Note. ABC = Aberrant Behavior Checklist; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ATX = atomoxetine; ES = effect size; HA = hyperactivity; HSQ = Home Situations Questionnaire; NC = noncompliance; ODD = oppositional defiance disorder; PT = parent training; SNAP = Swanson, Nolan and Pelham scale; SSQ = School Situations Questionnaire.

ES= 0.98;

ES= 0.80;

ES= 0.57;

ES= 1.00;

ES= 0.84;

ES= 0.60;

ES= 0.83;

ES= 0.68;

ES= 0.46;

ES= 0.47;

ES= 0.64;

ES= 0.67;

ES= 0.56;

ES= 0.69;

ES= 0.64;

ES=0.76;

ES= 0.86

ES= 0.61.

p≤ .05,

p≤ .01,

p≤ .001

In addition to parent SNAP and HSQ, significant group differences were also found on the parent ABC Hyperactivity/Noncompliance subscale for ATX+PT versus placebo (effect size = 0.69) and for ATX versus placebo (effect size = 0.56). PT was more effective than placebo for four additional variables: parent ABC Irritability (effect size = 0.56); parent ABC Inappropriate Speech (effect size = 0.86); SSQ (effect size = 0.67), and teacher ABC Inappropriate Speech (effect size = 0.61). Thus, ratings of home behavior showed robust and consistent effects for all three active treatments. The ratings obtained in school showed relatively few significant changes, and those that did occur were confined to PT+placebo.

Table 4 summarizes the CGI-Improvement at the last visit of study (week 10 or the last visit before exiting the study). CGI-I scores of “4” and “5 or 6” were further collapsed into one group for statistical analysis. Significant overall differences were noted for both ADHD ratings (p= .007) and Noncompliance ratings (p= .016). CGI-I significant improvement was defined as a score of “1” or “2.” The patients with ATX+PT treatment had the highest ADHD CGI-I improvement (48.4%), followed by ATX (46.9%), PT+placebo (29%), and placebo (19.4%). The two treatment groups with ATX had significantly more patients with ADHD improvement than the two placebo groups (p=.009), while the two PT groups were not significantly different from the two no-PT groups (p=0.58). On the other hand, ATX treatment had the highest Noncompliance improvement (43.8%), followed by PT+placebo (38.7%), ATX+PT (32.3%), and placebo (22.6%). The Noncompliance improvement was not statistically significantly different between the two ATX groups versus the two placebo groups (p=0.45), or between the two PT groups versus the two no-PT groups (p=0.86).

Table 4.

Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I) at the Last Visit (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder [ADHD] and Noncompliance)a

| CGI-I Score | ATX (n=32) |

ATX+PT (n=31) |

PT (n=31) |

Placebo (n=31) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD, n (%) | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 15 (46.9) | 15 (48.4) | 9 (29.0) | 6 (19.4) |

| 3 | 11 (34.4) | 8 (25.8) | 8 (25.8) | 5 (16.1) |

| 4 | 5 (15.6) | 6 (19.4) | 12 (38.7) | 17 (54.8) |

| 5 or 6 | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (9.7) |

| Noncompliance, n (%) | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 14 (43.8) | 10 (32.3) | 12 (38.7) | 7 (22.6) |

| 3 | 14 (43.8) | 13 (41.9) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) |

| 4 | 3 (9.4) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) | 12 (38.7) |

| 5 or 6 | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.2) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) |

Note: Scores of “4” and “5 or 6” were combined into one group for Chi square analysis. ATX = atomoxetine; PT = parent training.

Three participants did not have a CGI-I, as they did not return for a Week 1 visit.

For ADHD, p= .007. For Noncompliance, p= .016.

Adverse Events

In general, ATX was well-tolerated. The study drop-out rate in the two ATX treatment arms was 17% (n=11) versus 28% (n=18) in the two placebo arms (p=0.14). Of the 15 participants who left the study early due to an AE (e.g., increased irritability or a physical adverse event), only five were actually prescribed ATX (representing 8% of patients on active medication). Table 5 summarizes the AEs that were exhibited by ≥5% of patients during the trial. AEs for the ATX Alone and ATX + PT groups are collapsed under “ATX” while AEs for the placebo alone and PT+placebo groups are collapsed under “placebo.” Increased irritability was the most common AE across all groups, along with related complaints of increased agitation and aggression. Gastro-intestinal–related concerns were also frequently reported, including decreased appetite, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. The two ATX groups reported significantly greater complaints of decreased appetite and abdominal pain than that reported by the two placebo groups (ps=0.04 and 0.07, respectively). In addition, the ATX groups reported nonsignificantly greater concerns with sleep onset (p=.14). One SAE was reported at Week 8 involving a patient who was hospitalized for a seizure. The patient was on a stable dose of an anticonvulsant (levetiracetam) with no seizures during the prior 6-month period. AED levels were found to be subclinical, the SAE was rated as unrelated to ATX, and the ATX treatment was resumed.

Table 5.

Adverse Event Summary by Treatment Assignment (in Order of Prevalence)

| Adverse Event, n (%) | ATX+PT/ATX (n=64) | PT/Placebo (n=64) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irritability | 27 (42) | 29 (45) | .86 |

| Decreased appetite | 30 (47) | 18 (28) | .04 |

| Agitation | 19 (28) | 20 (31) | 1.00 |

| Difficult Sleep | 19 (30) | 11 (17) | .14 |

| Vomiting | 14 (22) | 10 (16) | .50 |

| Constipation | 7 (11) | 9 (14) | .79 |

| Abdominal pain | 10 (16) | 3 (5) | .08 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (5) | 4 (6) | 1.00 |

| Aggression | 2 (3) | 4 (6) | .68 |

Note: ATX = atomoxetine; PT = parent training.

DISCUSSION

The current study is only the third published RCT of ATX in ASD.16 It is the first study involving psychosocial intervention and ATX (both alone and in combination) for the treatment of ADHD and noncompliance in ASD. In addition, it is only the second RCT to examine combined drug and psychosocial treatment in ASD. Medication compliance and participation in PT were very high, and drop-outs were rare. Consistent with previous RCT findings, ATX was effective for treating ADHD symptoms in children with ASD. The overall response rate of 45–46% was higher than in a recent RCT of ATX and ASD, in which a 26% response rate was reported.18 The investigation ranks among the largest PT studies in ASD to date. As a result of this RCT, ATX is one of the best-studied pharmacological treatments for ADHD in ASD (along with treatment options such as methylphenidate or alpha-2 agonists). The overall response rate was fairly similar to that of studies of ASD involving methylphenidate.9,41 However, the response rates for both ATX and methylphenidate have consistently been lower than those reported among children without ASD39 −47% compared to 60% for ATX15 and 70% for methylphenidate.43 Interestingly, the effect sizes in the current study (0.59–0.98) were larger than effect sizes reported for methylphenidate in children with ASD (0.54)9 and comparable to effect sizes in children without ASD for ATX (0.64)15 and methylphenidate (0.99).44 However, these cross-study comparisons should be viewed with caution because research strategies differed considerably from the current investigation (e.g., fixed versus flexible dosing, crossover versus parallel design) but indicate that ATX may be a viable alternative to methylphenidate for children with ASD.

While the impact of combining PT with ATX was not significantly better than ATX alone, PT +placebo was significantly better than placebo alone in treating ADHD symptoms. Thus, although the findings did not support our hypothesis that ATX+PT would be more efficacious than either ATX or PT alone, we did find benefits from PT. PT is a relatively low-intensity, low-cost treatment that can be provided by experienced clinicians in an outpatient setting. The study results suggest that psychosocial treatments can reduce ADHD symptoms in the ASD population.

We did not observe benefits from either ATX or PT on the ODD scale of the SNAP-IV. However, this scale did not appear to be a good index of behavioral compliance. Indeed, parent-rated ODD at baseline was correlated with SNAP ADHD (r= .45) almost as highly as with HSQ (r= .48), and it correlated highest with ABC Irritability (r= .58) of the outcomes that were checked. Further, the ODD scale mean was not elevated in most cases. This is likely because (1) many ODD symptoms require considerable language skills (e.g., child often argues with adults, often blames others for his or her mistakes or misbehavior) or well-planned behavior (e.g., child deliberately annoys people, is often spiteful or vindictive) and (2) the sample was not selected for an ODD threshold, thus reducing the range available to show improvement. The ABC Irritability and HSQ/SSQ probably capture noncompliance and oppositionality better in this population.

The school findings were difficult to interpret. We observed high variability in the school data, likely due to a substantial number of children who initiated treatment in the late spring or summer and who had different teachers in the subsequent semester. Given that many of our patients were studied across different school years, it is perhaps not surprising that ATX did not significantly affect ADHD ratings in school. The PT+placebo condition accounted for the only significant improvements at school (not PT+ATX).

In terms of AEs, a significantly greater number of reports of decreased appetite and abdominal pain occurred among patients taking ATX than placebo. These AEs are also commonly reported AEs among TD children with ADHD treated with ATX.16 One interesting finding was the general lack of increased irritability reported by those in ATX in comparison to placebo. Whereas we noted that irritability was among the most commonly reported AEs ascribed to ATX in our review of children with DDs,16 the findings in this RCT actually showed higher rates of irritability, agitation, and aggression in the two placebo groups. One possible explanation might be the cautious dose adjustment schedule used in this study, starting with half the starting dose recommended in the package insert and splitting the daily dose, all of which was calculated to reduce side effects. A crossover study using the same dose adjustment schedule also found an effect on irritability practically indistinguishable from placebo (although the sample size was only 16 patients).40 This suggests implications for clinical practice. The mean dose levels used in the current study appear to have been slightly higher than those reported by other studies of ATX in the ASD population,16 possibly because physicians in the current study had the option of titrating to a maximum of 1.8 mg/kg if clinically indicated (versus a 1.2–1.4 mg/kg maximum dose in most other studies).

As noted, the differential drop-out rate between the two ATX arms and two placebo arms approached but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.14), with fewer discontinuations among those prescribed ATX. Of the patients who left the study early due to increased irritability or a physical AE, only five (8% of those on active medication) were prescribed ATX. This is in contrast to the RUPP methylphenidate study,9 in which 18% of patients dropped out related to inability to tolerate methylphenidate.

The racial and ethnic composition of the sample was mostly Caucasian, with no Hispanic Americans or Asian Americans. In addition, we may not have allowed enough time for PT to impact the behavior of study participants. After longer study period involving 16–24 weeks of PT, significant differences between the drug alone and drug plus PT conditions might have emerged. Additional limitations of the current report include the reliance on rating scales, absence of information on moderators, and lack of follow-up data; however, all of these limitations will be addressed in future reports. It is possible that the separate CGI ratings for ADHD and for Noncompliance may have been confounded (as the two concepts are somewhat interwoven). Finally, although the study was adequately powered to compare ATX versus no ATX and PT versus no PT, it may have been underpowered to compare the relative efficacy of each of the four treatment conditions (ATX, ATX+PT, placebo+PT, and placebo).

It is useful to compare the three FDA-approved classes of medication for treatment of ADHD in terms of the ASD population. These three drug classes appear to have fairly similar positive response rates (45%-55%), confirming ATX as a first-line treatment in this population. Second, despite similar response rates, the placebo-controlled effect sizes for ADHD symptoms may be greater for ATX than for alternative medications. Third, ATX’s side effect profile was relatively good, with minimal impact on appetite, weight, and irritability, in contrast to psychostimulants.9 ATX also has less potential for activation, with fewer families reporting increased agitation or moodiness than within the studies of stimulants. ATX appears to have fewer sedating effects than alpha-2 agonists.39 Conversely, ATX appears to require a number of weeks of treatment to achieve clinically significant improvement on behavior, while psychostimulants and alpha-2 agonists may improve target symptoms more rapidly. It is important to note that these results were obtained starting at half the package insert dose and splitting the daily dose to prevent side effects. Subsequent research should include a comparison of atomoxetine with other psychopharmacological treatments for ADHD along with the impact of psychosocial interventions such as PT.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health to Ohio State University (5R01MH079080), University of Pittsburgh (5R01MH079082-05), and University of Rochester (5R01 MH083247), by Eli Lilly and Co., who provided atomoxetine and placebo, and by the University of Rochester CTSA (UL1 RR024160) and Ohio State University CTSA (UL1TR001070) from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Dr. Pan served as the statistical expert for this research.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the guidance and supervision of the DSMB, consisting of Edwin H. Cook, Jr., MD (University of Illinois at Chicago), Walter J. Meyer, MD (University of Texas-Galveston), Carson R. Reider, PhD (Ohio State University), and Wesley K. Thompson, PhD (University of California-San Diego).

Dr. Handen has received research funding from Curemark, Eli Lilly and Co., and Roche. Dr. Aman has received research contracts, consulted with, served on advisory boards, or done investigator training for Biomarin Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CogState, Inc., Confluence Pharmaceutica, CogState Clinical Trials, Ltd., Coronado Biosciences, Forest Research, Hoffman-La Roche, Johnson and Johnson, MedAvante, Inc., Novartis, Pfizer, ProPhase LLC, and Supernus Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Arnold has received research funding from Curemark, Forest, Eli Lilly and Co., Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Shire, Young Living, NIH, and Autism Speaks, and has consulted with or been on advisory boards for Gowlings, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Sigma Tau, Shire, and Tris Pharma, and has received travel support from Noven. Dr. Hollway has received research funding from Forest, Sunovion, and Supernus. Dr. Hellings has received research funding from Sunovion, been an investigator for Forest and Shire, and has authorship collaboration with Roche. Dr. Hurt has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Drs. Hyman, Tumuluru, Lecavalier, Pan, Silverman, Rice, Jr., Mruzek, Levato, Smith, and Mss. Corbett-Dick, Buchan-Page, Brown, McAuliffe-Bellin, and Ryan report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leyfer OT, Folstein SE, Bacalman S, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in children with autism: Interview development and rates of disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:849–861. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg RE, Kaufmann WE, Law JK, Law PA. Parent report of community psychiatric comorbid diagnoses in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res Treatment. 2011;18:2011–2020. doi: 10.1155/2011/405849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sikora DM, Vora P, Coury DL, Rosenberg D. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms, adaptive functioning, and quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2012;130:S91–S97. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0900G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lecavalier L. Behavioral and emotional problems in young people with pervasive developmental disorders: relative prevalence, effects of subject characteristics, and empirical classification. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:1101–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G. Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2008;47:921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behavior problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J Intell Disabil Res. 2006;50:172–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coury D, Anagnostou E, Manning-Courtney P, et al. Use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;130:S69–S76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0900D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AC, Doshi J, Polsky DE. Psychotropic medication use among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e441–e448. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. Aman MG, Arnold LE, Ramadan Y, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of methylphenidate in children with hyperactivity associated with pervasive developmental disorders. Arch General Psychiat. 2005;62:1266–1274. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold LE. Handbooks in Health Care Co. 3rd edition. Newtown, PA: 2004. Contemporary Diagnosis Management ADHD; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnold LE. Methylphenidate vs Amphetamine: Comparative Review. J Attention Disorders. 2000;3:200–211. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handen BL, Johnson C, Lubetsky M. Efficacy and safety of methylphenidate in children with autistic disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;35:245–255. doi: 10.1023/a:1005548619694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gehlert DR, Gackenheimer SL, Robertson DW. Localization of rat brain binding sites for [3H]tomoxetine, an enantiomerically pure ligand for norephinephrine reuptake sites. Neurosci Lett. 1993;157:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90737-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong DT, Threlkeld PG, Best KL, Bymaster FP. A new inhibitor of norepinephrine uptake devoid of affinity for receptors in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;222:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz S, Correll C. Efficacy and safety of atomoxetine in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from a comprehensive meta-analysis and metaregression. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2014;53:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aman MG, Smith T, Arnold LE, et al. A review of atomoxetine in young people with developmental disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;16:1412–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold LE, Aman MG, Cook AM, et al. Atomoxetine for hyperactivity in autism spectrum disorders: Placebo-controlled crossover pilot trial. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2006;45:1196–1205. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000231976.28719.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harfterkamp M, van de Loo-Neus G, Minderaa RB, et al. A Randomized double-blind study of atomoxetine versus placebo for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2012;5:733–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazdin AE. Problem-solving skills training and parent management training for conduct disorder. In: Kazdin AE, editor. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells KC, Pelham WE, Kotkin RA, et al. Psychosocial treatment strategies in the MTA study: rationale, methods, and critical issues in design and implementation. J Abnorm Child Psych. 2000;28:483–505. doi: 10.1023/a:1005174913412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odom SL, Brown WH, Frey T, Karasu N, Smith-Canter LL, Strain PS. Evidence-based practices for young children with autism contributions for single-subject design research. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2003;18:166–175. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Scahill L, et al. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology. Medication and parent training in children with pervasive developmental disorders and serious behavior problems: Results from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2009;48:1143–1154. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181bfd669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bearss K, Lecavalier L, Minshawi N, et al. Toward an exportable parent training program for disruptive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3:170–180. doi: 10.2217/npy.13.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-Month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch General Psychiat. 1999;56:1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverman L, Hollway JA, Smith T, et al. A multisite trial of atomoxetine and parent training in children with autism spectrum disorders: Rationale and design challenges. Res Autism Spect Dis. 2014;8:899–907. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roid GH. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales. 5th ed. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullen EJ. Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutter M, Le Couteur A, Lord C. Autism Diagnostic Interview Revised. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders TR. 4th ed. Washington DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bussing R, Fernandez M, Harwood M, et al. Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms - psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment. 2008;15:317–328. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual of Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health US Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM), Psychopharmacology Research Branch; 1976. pp. 76–338. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barkley RA, Edelbrock C. Assessing situational variation in children’s problem behaviors: the Home and School Situations Questionnaires. In: Prinz R, editor. Advances in Behavioral Assessment of Children and Families. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press Inc; 1987. pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chowdhury M, Aman MG, Scahill L, et al. The Home Situations Questionnaire-PDD Version: Factor structure and Psychometric Properties. J Intell Disabil Res. 2010;54:281–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Altepeter TS, Breen MJ. The Home Situations Questionnaire (HSQ) and the School Situations Questionnaire (SSQ): Normative data and an evaluation of Psychometric Properties. J Psychoeduc Assess. 1989;7:312–322. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barkley RA, Edwards GH, Robin AL. Defiant Teens: A Clinician’s Manual for Assessment and Intervention. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. 196Y198. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist: A behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Def. 1985a;89:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. Psychometric characteristics of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist. Am J Ment Def. 1985b;489:492–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen J. Things I have learned (so far) Am Psychol. 1990;45:1304. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arnold LE, Aman MG, Cook AM, et al. Atomoxetine for hyperactivity in autism spectrum disorders: Placebo-controlled crossover pilot trial. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 2006;45:1196–1205. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000231976.28719.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Posey DJ, Aman MG, McCracken JT, et al. Positive effects of methylphenidate on inattention and hyperactivity in pervasive developmental disorders: An analysis of secondary measures. Biol Psychiat. 2007;61:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aman MG, Farmer CA, Hollway JA, Arnold LE. Treatment of Inattention, overactivity, and impulsiveness in autism spectrum disorders. Child Adolesc Psych Cl. 2008;17:713–738. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-Month randomized clinical trial of treatment Strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Arch General Psychiat. 1999;56:1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faraone SV. Using meta-analysis to compare the efficacy of medications for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in youths. P T. 2009;34:678–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]