Abstract

Functional metagenomics is a powerful experimental approach for studying gene function, starting from the extracted DNA of mixed microbial populations. A functional approach relies on the construction and screening of metagenomic libraries—physical libraries that contain DNA cloned from environmental metagenomes. The information obtained from functional metagenomics can help in future annotations of gene function and serve as a complement to sequence-based metagenomics. In this Perspective, we begin by summarizing the technical challenges of constructing metagenomic libraries and emphasize their value as resources. We then discuss libraries constructed using the popular cloning vector, pCC1FOS, and highlight the strengths and shortcomings of this system, alongside possible strategies to maximize existing pCC1FOS-based libraries by screening in diverse hosts. Finally, we discuss the known bias of libraries constructed from human gut and marine water samples, present results that suggest bias may also occur for soil libraries, and consider factors that bias metagenomic libraries in general. We anticipate that discussion of current resources and limitations will advance tools and technologies for functional metagenomics research.

Keywords: functional metagenomics, metagenomic library, cosmid library, fosmid library, pCC1FOS, cloning bias, library bias, RK2

The challenges of constructing large-insert metagenomic libraries

Functional metagenomics involves isolating DNA from microbial communities to study the functions of encoded proteins. It involves cloning DNA fragments, expressing genes in a surrogate host, and screening for enzymatic activities. Using this function-based approach allows for discovery of novel enzymes whose functions would not be predicted based on DNA sequence alone. Information from function-based analyses can then be used to annotate genomes and metagenomes derived solely from sequence-based analyses. Thus, functional metagenomics complements sequence-based metagenomics, analogous to how molecular genetics of model organisms has provided knowledge of gene function that is widely applicable in genomics.

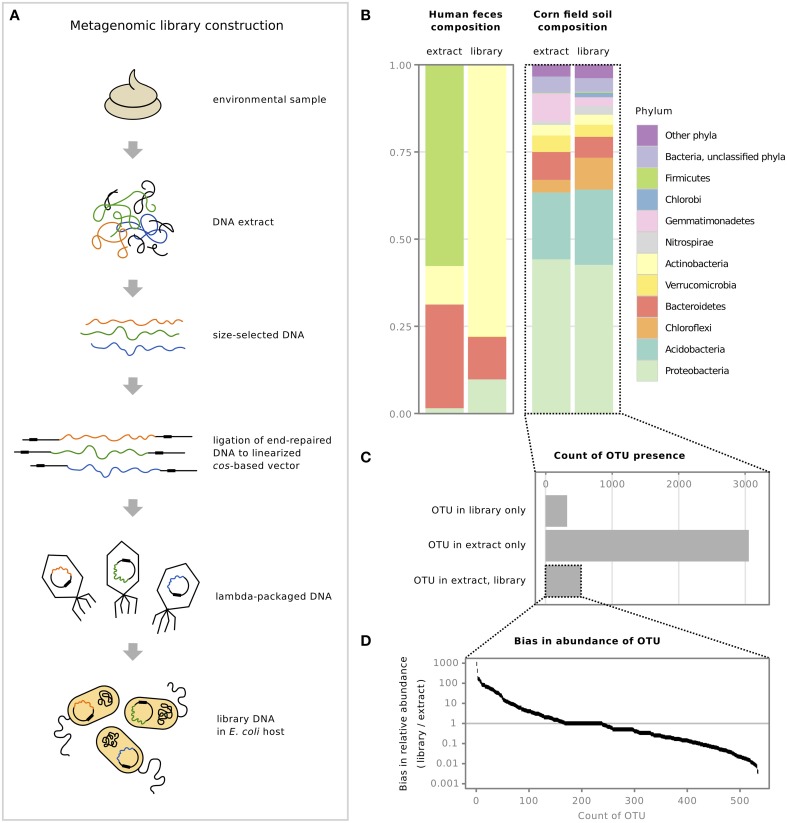

Functional metagenomics begins with the construction of a metagenomic library (Figure 1A). Cosmid- or fosmid-based libraries are often preferred due to their large and consistent insert size and high cloning efficiency. DNA is first extracted from the environmental sample of interest, then size-selected, end-repaired, and ligated to a cos-based vector, allowing packaging by lambda phage for subsequent transduction of Escherichia coli (Figure 1A). The resulting library contains relatively large insert DNA, typically 25–40 kb for cos-based vectors. With the steps involved, the construction of a metagenomic library can be laborious and time-consuming, requiring a high level of skill at the laboratory bench.

Figure 1.

Metagenomic libraries exhibit cloning bias when compared to the original environmental sample. (A) Steps involved in the construction of a metagenomic library, from original environmental sample to the final library in the E. coli host (adapted from Lam and Charles, 2015). (B) Relative abundance of bacterial phyla from two previously constructed metagenomic libraries, a human fecal library (Lam and Charles, 2015), and a corn field soil library (Cheng et al., 2014), compared to their original sample DNA extracts. (C) Number of OTUs identified from corn field soil DNA extract and library, and whether the OTUs were present in the library sample only, the extract sample only, or present in both. (D) Examination of cloning bias by comparing the relative abundance of OTUs that were present in both the DNA extract and the cosmid library, shown on a log scale; horizontal line at 1 denotes equal relative abundance in both samples.

There are several technically challenging steps in library construction. First, the extracted DNA must be of sufficient length for efficient packaging into lambda phage heads (Parks and Graham, 1997). Extraction usually employs gentle lysis to avoid shearing DNA (Zhou et al., 1996) but even so it may be difficult to achieve large fragment sizes (Kakirde et al., 2010). We find that starting with crude DNA extracts containing at least ~75 kb fragments leads to high-quality libraries and it is crucial to check the fragment size range by pulsed-field electrophoresis before proceeding. A particularly useful and affordable molecular ladder for pulsed-field gels is self-ligated lambda DNA, which can be easily prepared and results in bands at approximately 50, 100, and 150 kb. A freeze-grinding step prior to extraction (Lee and Hallam, 2009) can substantially improve cell lysis. Although this step may fragment DNA (Brady, 2007), we find it does not hinder library construction, consistent with previous work showing that freeze-grinding results in minimal shearing (Zhou et al., 1996).

Extracts are often contaminated with compounds that co-purify with DNA, requiring additional purification steps that may lead to sample loss. Common contaminants in soil-derived DNA extracts are humic acids, which may interfere with enzymatic reactions (Tebbe and Vahjen, 1993). Non-linear electrophoresis is effective for contaminant removal (Pel et al., 2009) and generates purified and concentrated DNA suitable for PCR or metagenomic analysis (Engel et al., 2012), yet requires specialized equipment. We have found that for library construction, humic acids can simply be allowed to run off the gel during pulsed-field electrophoresis of crude extract for size-selection because they migrate much faster than large DNA fragments. Alternatively, to avoid contaminating the circulating buffer, electrophoresis can be paused after humic acids have formed a front, the part of the gel containing the humic acids excised, and then this region replaced with fresh gel (Cheng et al., 2014). Others have reported that contaminating nucleases are effectively inhibited by treating extracted DNA in an agarose plug with sodium chloride and formamide (Liles et al., 2008).

After the DNA has been size-selected and purified, it must be end-repaired and ligated to a desphosphorylated, blunt-ended vector. To ensure proper size range before ligation, the DNA can be checked for co-migration with the largest band of a lambda-HindIII ladder on an agarose gel (Brady, 2007) or the sample can be run on a pulsed-field gel for a more accurate size assessment. The end-repair is a challenging step because there is no simple way to confirm that ends are indeed blunt following the reaction. We use a small amount of the ligation to transform E. coli prior to the costly packaging step; resulting transformants indicate the presence of circular DNA molecules arising from ligation of successfully blunt-ended fragments. Though the ligation conditions may not favor formation of circular molecules, this is our best proxy for successful end-repair.

Other challenges include the sensitivity of packaging extracts and preparation of purified digested and dephosphorylated vector DNA for ligation. Although excellent commercial products are available for both, in-house vector preparation may still be required when specific expression hosts are to be used in functional screening outside the host range of available commercial vectors (Wexler et al., 2005; Craig et al., 2010; Troeschel et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2014). The culminating step of library construction is the transduction of E. coli, and although it is possible to generate many thousands of clones with the first attempt, troubleshooting may be required to increase library size. When transduction results in a disappointingly small number of transductants (zero in the worst case!), it is not easy to determine the cause.

Indeed, metagenomic library construction is in many ways an art that takes time and practice to master. Given the substantial challenges and costs associated with library construction, as well as possible difficulties in obtaining rare environmental samples, a clear corollary is that we ought to find ways to maximize these valuable resources for shared benefit. In particular, collections of metagenomic libraries that can be used in a variety of hosts would be extremely valuable if able to be accessed by the scientific community. We have previously made our libraries publicly available (Neufeld et al., 2011) and we continue to advocate for increased sharing (Charles and Neufeld, 2015). Though there are obvious administrative obstacles, services such as Addgene (Herscovitch et al., 2012) may facilitate these efforts.

Making the most of what we have: leveraging existing libraries

Due to the difficulties of library construction, commercial products that aid in generation of libraries are popular. Indeed, one widely used cloning-ready commercial vector is pCC1FOS (Genbank accession EU140751; Epicentre Biotechnologies). In recent years, as functional metagenomics has gained traction, metagenomic libraries from remarkably diverse environments have been constructed using pCC1FOS (Table 1). The pCC1FOS vector has several advantages. It carries a chloramphenicol resistance (cat) marker that is superior to the common ampicillin resistance (bla) marker, obviating the occurrence of satellite colonies associated with beta-lactamase secretion that can be problematic for the dense platings often required for library construction. In addition to an F plasmid oriV for single-copy maintenance, pCC1FOS also carries an oriV from the RK2 plasmid. The RK2 oriV is broad-host-range, conferring replication ability in diverse members of the Proteobacteria (Ayres et al., 1993), but requires the trfA gene product for replication and results in an estimated 15 copies per cell (Durland and Helinski, 1990). Though trfA is not carried by the fosmid, it can be provided in trans; notably, the commercial E. coli strain EPI300 (Epicentre Biotechnologies) carries trfA under the control of an inducible promoter that is advertised to increase copy number from 1 copy per cell to 10–200 copies. The strain likely possesses a trfA copy-up mutant allele under control of araC-PBAD, which is induced by L-arabinose (Wild et al., 2002). In the past, we preferred HB101 as a library host due to its receptiveness to transduction, but EPI300 appears to transduce at least as well as, if not better than, HB101. It also has the advantages of being an endA1 mutant and supporting copy-number inducibility, allowing for less-degraded and higher-yield plasmid preparations.

Table 1.

Examples of metagenomic libraries constructed from diverse environmental samples using cloning vector pCC1FOS/pCC2FOS or derivatives.

| Environment | Library vector; screening host, if relevant | References |

|---|---|---|

| HOST-ASSOCIATED ENVIRONMENTS | ||

| Bovine rumen | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Wang et al., 2013 |

| Elephant feces | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Rabausch et al., 2013 |

| Human distal ileum | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Cecchini et al., 2013 |

| Human feces | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Jones et al., 2008 |

| Human feces (pescatarian) | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Tasse et al., 2010 |

| Marine sponge | pCC1FOS | Yung et al., 2009 |

| Termite gut | pCC1FOS, pCC2FOS; E. coli | Warnecke et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2011 |

| EXTREME ENVIRONMENTS | ||

| Alaskan soil | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Allen et al., 2009 |

| Alaskan floodplain soil | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Williamson et al., 2005 |

| Antarctic Pennisula meltwater | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Ferrés et al., 2015 |

| Glacial ice | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Simon et al., 2009 |

| Hot spring sediment and biofilm | pCT3FK; E. coli, Thermus thermophilus | Leis et al., 2015 |

| Hydrothermal fluids | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Böhnke and Perner, 2015 |

| MARINE OR FRESHWATER ENVIRONMENTS | ||

| Bog | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Sommer et al., 2010 |

| Marine sediment | pRS44; Pseudomonas fluorescens, Xanthomonas campestris | Aakvik et al., 2009 |

| Ocean tidal flat sediment | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Lee et al., 2006, 2015 |

| Ocean water column | pCC1FOS | DeLong et al., 2006 |

| River sediment | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Rabausch et al., 2013 |

| POLLUTED ENVIRONMENTS | ||

| Crude oil-contaminated shore | pMPO579; E. coli* | Terrón-González et al., 2013 |

| Polluted river | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Vercammen et al., 2013 |

| AGRICULTURAL, ENGINEERED, OR OTHER ENVIRONMENTS | ||

| Activated sludge | pCC1FOS, pCC2FOS; E. coli | Suenaga et al., 2007; Zhang and Han, 2009 |

| Compost, leaf branch | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Sulaiman et al., 2012 |

| Compost, lumber waste | pCT3FK; E. coli, Thermus thermophilus | Leis et al., 2015 |

| Compost, wood/plant debris/manure | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Ohlhoff et al., 2015 |

| Decomposing leaf litter | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Nyyssönen et al., 2013 |

| Orchard soil | pCC1FOS; E. coli | Donato et al., 2010 |

| Sugarcane bagasse | pCC1FOS | Mhuantong et al., 2015 |

Libraries that are based on the commercial pCC1FOS or pCC2FOS vector can be screened in any RK2-compatible host that expresses the trfA gene product required for the broad-host-range RK2 oriV origin of replication.

modified strains derived from E. coli EPI300 to increase transcription.

Despite its popularity, pCC1FOS has some disadvantages that make resulting libraries less versatile than they could be. First, pCC1FOS does not possess an oriT that would allow the fosmid to be efficiently transferred by conjugation, mediated by a helper plasmid, to other species or strains that may be more suitable for heterologous expression. To achieve conjugation capabilities, we have added the RK2 oriT to pCC1FOS (Lam and Charles, unpublished), as have others (Aakvik et al., 2009; Buck, 2012; Terrón-González et al., 2013). To enable conjugation after library construction has already taken place, others have retrofitted individual pCC1FOS-based clones with an oriT (Li et al., 2011; Buck, 2012). These modifications illustrate the need for fosmid and cosmid vector design to include the oriT so that duplication of work can be avoided. It is possible that transformation can be used to transfer libraries to other hosts, but only for recipients that are amenable to those techniques and that will not reject DNA that has been synthesized in E. coli due to the presence of host restriction-modification systems. In some cases, it will be desirable to modify these host strains by deleting the restriction-modification genes.

Given that the broad-host-range oriV is used to achieve a higher copy number in EPI300 expressing the trfA gene, another disadvantage of pCC1FOS is that trfA is not included on the vector. The consequence is that species that would otherwise be able to use the oriV cannot replicate pCC1FOS. It is not surprising then that for the vast majority of studies highlighted here (Table 1), E. coli was used as the screening host. This is a disadvantage for functional metagenomics as different clones can be isolated from the same metagenomic library when different screening hosts are used (Martinez et al., 2004; Craig et al., 2010). We found that using the legume-symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti as a host results in a much greater diversity of clones than E. coli when screening our corn field soil metagenomic library for beta-galactosidase activity, though this greater diversity does not appear to be related to phylogenetic distance of the origin of the cloned DNA to the surrogate host (Cheng et al., in preparation). The importance of devising systems that allow for functional screening in diverse expression hosts has been reviewed by others (Uchiyama and Miyazaki, 2009; Taupp et al., 2011; Ekkers et al., 2012; Liebl et al., 2014), but what of the large number of libraries that have already been constructed? Can we make use of them for screening in non-E. coli hosts? The libraries listed in Table 1, as well as potentially many other metagenomic libraries constructed using pCC1FOS or derivatives, would be accessible to any RK2-compatible host if a copy of the trfA gene were also made available. This solution has already been applied: one group inserted the trfA gene into the chromosome of the Gammaproteobacteria species Pseudomonas fluorescens and Xanthomonas campestris for screening of libraries constructed using a pCC1FOS derivative (Aakvik et al., 2009). Another group inserted araC-PBAD-trfA into the E. coli EL350 chromosome to give copy number inducibility to the lambda Red recombineering strain (Westenberg et al., 2010). The introduction of trfA into RK2-compatible species is a straightforward way to expand the range of expression hosts for existing pCC1FOS-based libraries.

An alternative to inserting the trfA gene into desired expression hosts is to modify the vector for integration into the host genome, bypassing the requirement for trfA. This strategy has been employed to integrate clones into a target locus in the genome of the thermophile Thermus thermophilus for functional screening, by modifying pCC1FOS to include a selectable marker as well as regions for homologous recombination (Angelov et al., 2009). In our lab, pCC1FOS was modified to carry ΦC31 att sites (Heil and Charles, unpublished) for integrase-mediated site-specific recombination of cloned insert DNA into the genomes of landing pad strains, including S. meliloti and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Heil et al., 2012). As a general strategy, however, chromosomal integration is potentially less useful than clone maintenance due to the difficulty in retrieving the integrated DNA for manipulation, including DNA sequence analysis, when non-arrayed (i.e., pooled) libraries have been screened.

Knowing the extent of what we have: examining cloning bias

Beyond the practical questions of how to optimize vectors for library construction and how to maximize valuable existing libraries, there is a technical question that we find particularly interesting: how much of the sequence diversity present in original DNA extracts is captured in constructed libraries, and what affects this? Though not so much a concern for functional screens, it is interesting to consider the factors that influence library representativeness; elucidating these factors may lead to development of better strategies for accessing the full potential of environmental metagenomes. We previously used shotgun sequencing to examine bias in a human fecal library (Lam and Charles, 2015) and here we also present the results of 16S rRNA gene sequencing to examine bias in a corn field soil library (Cheng et al., 2014); see Supplementary Material for details. Both libraries were constructed using the RK2-based cosmid pJC8 (Genbank accession KC149513).

The bias discussed here is from comparing DNA extracted from the sample to the final cloned library DNA isolated from E. coli (Figure 1A). Analysis at the phylum-level showed that although the fecal library differed substantially in the relative abundance of phyla compared to its corresponding extract, the relative abundance of phyla in the corn field soil library seemed similar to its extract (Figure 1B). We present these results for the soil library but exercise caution in their interpretation as the majority of 16S rRNA gene sequences from the metagenomic library sample was E. coli contamination, despite treating the library cosmid DNA preparation with Plasmid-Safe DNase to remove host genomic DNA prior to PCR. After subtracting E. coli host sequences, approximately 30,000 sequences remained to represent the metagenomic library (see Supplementary Material for details). The high level of host contamination could be due to preferential amplification of template during PCR based on differences in DNA conformation: though present in very small quantities, linear DNA may be more efficiently amplified over supercoiled or closed circular plasmid DNA (Chen et al., 2007). This issue of E. coli host contamination in 16S rRNA gene analysis needs to be addressed for future examination of bias in metagenomic libraries.

When we examined the soil samples more closely, we found that the similarity of the library and extract at the phylum level does not extend to the “species” level: examination of the individual OTUs in each sample revealed that only a small fraction of OTUs were shared between the library and original sample (Figure 1C). Interestingly, our analysis indicated that there were a number of OTUs in the library that were not identified in the extract sample (Figure 1C) and although this number is halved when the library data are compared to extract data that have not been rarefied (data not shown), they nevertheless remain, indicating that these OTUs are either extremely rare in the original sample and their DNA is preferentially cloned or that the identification of these OTUs is due to sequencing errors. A further analysis of the OTU fraction that is shared between extract and library samples shows a large range in the bias in relative abundance of each OTU, with some OTUs exhibiting ~1000-fold overrepresentation and others ~1000-fold underrepresentation in the library (Figure 1D). While there may be concern that 16S rRNA gene profiles of libraries compared to extracts may not provide an accurate comparison of cloned DNA content in general, we have previously shown from analysis of shotgun sequence data that for large-insert RK2 oriV-based cosmid libraries, 16 S rRNA gene content tracks well with genomic content (Lam and Charles, 2015). The analysis of the corn field DNA extract and corresponding metagenomic library suggests that though the overall relative abundance of phyla may remain similar, bias is occurring on the level of individual OTUs.

The fact that certain taxa are under- or overrepresented might not pose a barrier to screening, but it may be useful to know what sequences are not likely to be captured in libraries. Several studies that have compared shotgun sequencing of original samples to corresponding metagenomic libraries from marine water (Temperton et al., 2009; Ghai et al., 2010; Danhorn et al., 2012), as well as our own comparative work on feces (Lam and Charles, 2015), have shown that AT-rich sequences are underrepresented in libraries. Our analysis—in which we compared promoter consensus sequences between extract and library samples—lends support to the hypothesis that the bias is related to spurious transcription of metagenomic DNA from AT-rich sequences recognized as σ70 promoters in the E. coli library host (Lam and Charles, 2015) although other factors may be contributing, such as gene product toxicity (Sorek et al., 2007). Notably, we have shown that DNA fragmentation is not a cause of bias (Lam and Charles, 2015). The specific factors affecting the “clonability” of DNA, and the mechanisms that lead to DNA exclusion, still need to be experimentally determined.

The stability of foreign DNA in E. coli is influenced by the vector copy number and, as a result, single-copy fosmids may be ideal as the library backbone (Kim et al., 1992), although the success of some functional screens may be dependent on a higher gene dose. Plasmid vectors that are not cos-based provide an alternative where cloning is substantially less difficult as large-fragment DNA need not be isolated and packaging and transduction are not required; the disadvantages, however, are that a smaller insert size means that larger operons will not be intact, and if the plasmid has a high copy number—true of conventional cloning vectors—this may lead to greater insert instability and exclusion (Lam and Charles, 2015). Other alternatives to fosmid vectors include BACs (Kakirde et al., 2011), which have the ability to capture even larger insert sizes at approximately 100 kb on average (Kakirde et al., 2010), and linear vectors, which may provide exceptional stability (Godiska et al., 2010). However, cos-based vectors are likely to remain popular for their advantages: the availability of high-quality commercial packaging extracts, greater efficiency of transduction over transformation, and decreased probability of insert concatemers due to the phage head upper size limit. Though there exists variety in library cloning vectors, further work is required to understand how and to what extent cloning vector choice and strategy impacts library sequence bias.

Concluding remarks

Depending on the target activity, functional screens can exhibit a low hit rate (Uchiyama and Miyazaki, 2009) the reasons for which might include barriers at the level of both transcription and translation. Improving E. coli as a screening host to address these problems will likely improve future hit rates. Examples include introducing heterologous sigma factors to guide RNA polymerase to otherwise untranscribed regions (Gaida et al., 2015), employing T7 RNA polymerase to help drive transcription (Terrón-González et al., 2013), as well as forming hybrid ribosomes (Kitahara et al., 2012) that may influence expression. Nevertheless, it will be important to move beyond E. coli into different screening hosts, particularly for the complementation of mutant phenotypes not possible in E. coli. The identification of obstacles to cloning and screening will aid in the development of new tools and technologies for functional metagenomics (Engel et al., 2013), providing us with greater reach in terms of what we are able to gather from functional screens. The refinement of methods will be crucial in bioprospecting for novel enzymes and compounds as well as for the determination of gene function that will guide the development of reliable models of microbial ecosystem functioning.

Author contributions

KL and TC conceived the ideas. JC prepared DNA from the soil-related samples. KE carried out V3 region PCR on the soil-related samples and managed sequencing sample submission. KL analyzed the sequence data, made the figures, performed the literature review, and wrote the paper. TC, JN, JC, and KE revised the manuscript. TC and JN provided reagents and materials. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Research funding was provided by a Strategic Projects Grant (381646–09) from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, by Genome Canada for the project “Microbial Genomics for Biofuels and Co-Products from Biorefining Processes,” and by a University of Waterloo CIHR Research Incentive Fund. KL was supported by a CGS-D scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Brent Seuradge for advice on the AXIOME2 pipeline, Michael J. Lynch for help with 16S rRNA gene analysis, and Michael W. Hall for assistance in AXIOME2 and BIOM-related issues. We acknowledge funding from NSERC (Strategic Projects Grant), Genome Canada and Genome Prairie, and the McMaster-Waterloo Bioinformatics Initiative. KL was supported by a CIHR CGS-D.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01196

References

- Aakvik T., Degnes K. F., Dahlsrud R., Schmidt F., Dam R., Yu L., et al. (2009). A plasmid RK2-based broad-host-range cloning vector useful for transfer of metagenomic libraries to a variety of bacterial species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 296, 149–158. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen H. K., Moe L. A., Rodbumrer J., Gaarder A., Handelsman J. (2009). Functional metagenomics reveals diverse beta-lactamases in a remote Alaskan soil. ISME J. 3, 243–251. 10.1038/ismej.2008.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelov A., Mientus M., Liebl S., Liebl W. (2009). A two-host fosmid system for functional screening of (meta)genomic libraries from extreme thermophiles. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 32, 177–185. 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres E. K., Thomson V. J., Merino G., Balderes D., Figurski D. H. (1993). Precise deletions in large bacterial genomes by vector-mediated excision (VEX): the trfA gene of promiscuous plasmid RK2 is essential for replication in several Gram-negative hosts. J. Mol. Biol. 230, 174–185. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhnke S., Perner M. (2015). A function-based screen for seeking RubisCO active clones from metagenomes: novel enzymes influencing RubisCO activity. ISME J. 9, 735–745. 10.1038/ismej.2014.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady S. F. (2007). Construction of soil environmental DNA cosmid libraries and screening for clones that produce biologically active small molecules. Nat. Protoc. 2, 1297–1305. 10.1038/nprot.2007.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck J. D. (2012). Physiological Effects of Heterologous Expression of Proteorhodopsin Photosystems. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/71464

- Cecchini D. A., Laville E., Laguerre S., Robe P., Leclerc M., Doré J., et al. (2013). Functional metagenomics reveals novel pathways of prebiotic breakdown by human gut bacteria. PLoS ONE 8:e72766. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles T. C., Neufeld J. D. (2015). Open resource metagenomics, in Encyclopedia of Metagenomics, ed Nelson K. E. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 573–575. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Kadlubar F. F., Chen J. Z. (2007). DNA supercoiling suppresses real-time PCR: a new approach to the quantification of mitochondrial DNA damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1377–1388. 10.1093/nar/gkm010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Pinnell L., Engel K., Neufeld J. D., Charles T. C. (2014). Versatile broad-host-range cosmids for construction of high quality metagenomic libraries. J. Microbiol. Methods 99, 27–34. 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig J. W., Chang F.-Y., Kim J. H., Obiajulu S. C., Brady S. F. (2010). Expanding small-molecule functional metagenomics through parallel screening of broad-host-range cosmid environmental DNA libraries in diverse Proteobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 1633–1641. 10.1128/AEM.02169-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhorn T., Young C. R., DeLong E. F. (2012). Comparison of large-insert, small-insert and pyrosequencing libraries for metagenomic analysis. ISME J. 6, 2056–2066. 10.1038/ismej.2012.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong E. F., Preston C. M., Mincer T., Rich V., Hallam S. J., Frigaard N.-U., et al. (2006). Community genomics among stratified microbial assemblages in the ocean's interior. Science 311, 496–503. 10.1126/science.1120250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato J. J., Moe L. A., Converse B. J., Smart K. D., Berklein F. C., McManus P. S., et al. (2010). Metagenomic analysis of apple orchard soil reveals antibiotic resistance genes encoding predicted bifunctional proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4396–4401. 10.1128/AEM.01763-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durland R. H., Helinski D. R. (1990). Replication of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2: direct measurement of intracellular concentrations of the essential TrfA replication proteins and their effect on plasmid copy number. J. Bacteriol. 172, 3849–3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekkers D. M., Cretoiu M. S., Kielak A. M., Elsas J. D. (2012). The great screen anomaly—a new frontier in product discovery through functional metagenomics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93, 1005–1020. 10.1007/s00253-011-3804-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel K., Ashby D., Brady S. F., Cowan D. A., Doemer J., Edwards E. A., et al. (2013). Meeting report: 1st international functional metagenomics workshop May 7-8, 2012, St. Jacobs, Ontario, Canada. Stand. Genomic Sci. 8, 106–111. 10.4056/sigs.3406845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel K., Pinnell L., Cheng J., Charles T. C., Neufeld J. D. (2012). Nonlinear electrophoresis for purification of soil DNA for metagenomics. J. Microbiol. Methods 88, 35–40. 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrés I., Amarelle V., Noya F., Fabiano E. (2015). Construction and screening of a functional metagenomic library to identify novel enzymes produced by Antarctic bacteria. Adv. Polar Sci. 26, 96–101. 10.13679/j.advps.2015.1.00096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaida S. M., Sandoval N. R., Nicolaou S. A., Chen Y., Venkataramanan K. P., Papoutsakis E. T. (2015). Expression of heterologous sigma factors enables functional screening of metagenomic and heterologous genomic libraries. Nat. Commun. 6:7045. 10.1038/ncomms8045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghai R., Martin-Cuadrado A.-B., Molto A. G., Heredia I. G., Cabrera R., Martin J., et al. (2010). Metagenome of the Mediterranean deep chlorophyll maximum studied by direct and fosmid library 454 pyrosequencing. ISME J. 4, 1154–1166. 10.1038/ismej.2010.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godiska R., Mead D., Dhodda V., Wu C., Hochstein R., Karsi A., et al. (2010). Linear plasmid vector for cloning of repetitive or unstable sequences in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:e88. 10.1093/nar/gkp1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil J. R., Cheng J., Charles T. C. (2012). Site-specific bacterial chromosome engineering: ΦC31 integrase mediated cassette exchange (IMCE). J. Vis. Exp. e3698 10.3791/3698 Available online at: http://www.jove.com/video/3698/site-specific-bacterial-chromosome-engineering-c31-integrase-mediated [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herscovitch M., Perkins E., Baltus A., Fan M. (2012). Addgene provides an open forum for plasmid sharing. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 316–317. 10.1038/nbt.2177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. V., Begley M., Hill C., Gahan C. G. M., Marchesi J. R. (2008). Functional and comparative metagenomic analysis of bile salt hydrolase activity in the human gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13580–13585. 10.1073/pnas.0804437105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakirde K. S., Parsley L. C., Liles M. R. (2010). Size does matter: application-driven approaches for soil metagenomics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 1911–1923. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakirde K. S., Wild J., Godiska R., Mead D. A., Wiggins A. G., Goodman R. M., et al. (2011). Gram negative shuttle BAC vector for heterologous expression of metagenomic libraries. Gene 475, 57–62. 10.1016/j.gene.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U.-J., Shizuya H., de Jong P. J., Birren B., Simon M. I. (1992). Stable propagation of cosmid sized human DNA inserts in an F factor based vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 1083–1085. 10.1093/nar/20.5.1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara K., Yasutake Y., Miyazaki K. (2012). Mutational robustness of 16S ribosomal RNA, shown by experimental horizontal gene transfer in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 19220–19225. 10.1073/pnas.1213609109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K. N., Charles T. C. (2015). Strong spurious transcription likely contributes to DNA insert bias in typical metagenomic clone libraries. Microbiome 3:22. 10.1186/s40168-015-0086-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.-H., Choi S.-L., Rha E., Kim S. J., Yeom S.-J., Moon J.-H., et al. (2015). A novel psychrophilic alkaline phosphatase from the metagenome of tidal flat sediments. BMC Biotechnol. 15:1. 10.1186/s12896-015-0115-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. H., Lee C. H., Oh T. K., Song J. K., Yoon J. H. (2006). Isolation and characterization of a novel lipase from a metagenomic library of tidal flat sediments: evidence for a new family of bacterial lipases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 7406–7409. 10.1128/AEM.01157-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Hallam S. J. (2009). Extraction of high molecular weight genomic DNA from soils and sediments. J. Vis. Exp. 33:e1569. 10.3791/1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leis B., Angelov A., Mientus M., Li H., Pham V. T. T., Lauinger B., et al. (2015). Identification of novel esterase-active enzymes from hot environments by use of the host bacterium Thermus thermophilus. Front. Microbiol. 6:275. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Zhang F., Kelly W. L. (2011). Heterologous production of thiostrepton A and biosynthetic engineering of thiostrepton analogs. Mol. Biosyst. 7, 82–90. 10.1039/C0MB00129E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebl W., Angelov A., Juergensen J., Chow J., Loeschcke A., Drepper T., et al. (2014). Alternative hosts for functional (meta)genome analysis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 8099–8109. 10.1007/s00253-014-5961-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liles M. R., Williamson L. L., Rodbumrer J., Torsvik V., Goodman R. M., Handelsman J. (2008). Recovery, purification, and cloning of high-molecular-weight DNA from soil microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 3302–3305. 10.1128/AEM.02630-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Yan X., Zhang M., Xie L., Wang Q., Huang Y., et al. (2011). Microbiome of fungus-growing termites: a new reservoir for lignocellulase genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 48–56. 10.1128/AEM.01521-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A., Kolvek S. J., Yip C. L. T., Hopke J., Brown K. A., MacNeil I. A., et al. (2004). Genetically modified bacterial strains and novel bacterial artificial chromosome shuttle vectors for constructing environmental libraries and detecting heterologous natural products in multiple expression hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 2452–2463. 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2452-2463.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhuantong W., Charoensawan V., Kanokratana P., Tangphatsornruang S., Champreda V. (2015). Comparative analysis of sugarcane bagasse metagenome reveals unique and conserved biomass-degrading enzymes among lignocellulolytic microbial communities. Biotechnol. Biofuels 8:16. 10.1186/s13068-015-0200-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld J. D., Engel K., Cheng J., Moreno-Hagelsieb G., Rose D. R., Charles T. C. (2011). Open resource metagenomics: a model for sharing metagenomic libraries. Stand. Genomic Sci. 5, 203–210. 10.4056/sigs.1974654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyyssönen M., Tran H. M., Karaoz U., Weihe C., Hadi M. Z., Martiny J. B. H., et al. (2013). Coupled high-throughput functional screening and next generation sequencing for identification of plant polymer decomposing enzymes in metagenomic libraries. Front. Microbiol. 4:282. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlhoff C. W., Kirby B. M., Van Zyl L., Mutepfa D. L. R., Casanueva A., Huddy R. J., et al. (2015). An unusual feruloyl esterase belonging to family VIII esterases and displaying a broad substrate range. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 118, 79–88. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2015.04.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parks R. J., Graham F. L. (1997). A helper-dependent system for adenovirus vector production helps define a lower limit for efficient DNA packaging. J. Virol. 71, 3293–3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pel J., Broemeling D., Mai L., Poon H.-L., Tropini G., Warren R. L., et al. (2009). Nonlinear electrophoretic response yields a unique parameter for separation of biomolecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14796–14801. 10.1073/pnas.0907402106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabausch U., Juergensen J., Ilmberger N., Böhnke S., Fischer S., Schubach B., et al. (2013). Functional screening of metagenome and genome libraries for detection of novel flavonoid-modifying enzymes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4551–4563. 10.1128/AEM.01077-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C., Herath J., Rockstroh S., Daniel R. (2009). Rapid identification of genes encoding DNA polymerases by function-based screening of metagenomic libraries derived from glacial ice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 2964–2968. 10.1128/AEM.02644-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M. O. A., Church G. M., Dantas G. (2010). A functional metagenomic approach for expanding the synthetic biology toolbox for biomass conversion. Mol. Syst. Biol. 6:360. 10.1038/msb.2010.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R., Zhu Y., Creevey C. J., Francino M. P., Bork P., Rubin E. M. (2007). Genome-wide experimental determination of barriers to horizontal gene transfer. Science 318, 1449–1452. 10.1126/science.1147112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga H., Ohnuki T., Miyazaki K. (2007). Functional screening of a metagenomic library for genes involved in microbial degradation of aromatic compounds. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 2289–2297. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman S., Yamato S., Kanaya E., Kim J.-J., Koga Y., Takano K., et al. (2012). Isolation of a novel cutinase homolog with polyethylene terephthalate-degrading activity from leaf-branch compost by using a metagenomic approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1556–1562. 10.1128/AEM.06725-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasse L., Bercovici J., Pizzut-Serin S., Robe P., Tap J., Klopp C., et al. (2010). Functional metagenomics to mine the human gut microbiome for dietary fiber catabolic enzymes. Genome Res. 11, 1605–1612. 10.1101/gr.108332.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupp M., Mewis K., Hallam S. J. (2011). The art and design of functional metagenomic screens. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22, 1–8. 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebbe C. C., Vahjen W. (1993). Interference of humic acids and DNA extracted directly from soil in detection and transformation of recombinant DNA from bacteria and a yeast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 2657–2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temperton B., Field D., Oliver A., Tiwari B., Mühling M., Joint I., et al. (2009). Bias in assessments of marine microbial biodiversity in fosmid libraries as evaluated by pyrosequencing. ISME J. 3, 792–796. 10.1038/ismej.2009.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrón-González L., Medina C., Limón-Mortés M. C., Santero E. (2013). Heterologous viral expression systems in fosmid vectors increase the functional analysis potential of metagenomic libraries. Sci. Rep. 3:1107. 10.1038/srep01107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troeschel S. C., Drepper T., Leggewie C., Streit W. R., Jaeger K.-E. (2010). Novel tools for the functional expression of metagenomic DNA, in Metagenomics: Methods and Protocols Methods in Molecular Biology, eds Streit W. R., Daniel R. (New York, NY: Humana Press; ), 117–139. 10.1007/978-1-60761-823-2_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama T., Miyazaki K. (2009). Functional metagenomics for enzyme discovery: challenges to efficient screening. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 616–622. 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercammen K., Garcia-Armisen T., Goeders N., Van Melderen L., Bodilis J., Cornelis P. (2013). Identification of a metagenomic gene cluster containing a new class A beta-lactamase and toxin-antitoxin systems. Microbiologyopen 2, 674–683. 10.1002/mbo3.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Hatem A., Catalyurek U. V., Morrison M., Yu Z. (2013). Metagenomic insights into the carbohydrate-active enzymes carried by the microorganisms adhering to solid digesta in the rumen of cows. PLoS ONE 8:e78507. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke F., Luginbühl P., Ivanova N., Ghassemian M., Richardson T. H., Stege J. T., et al. (2007). Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature 450, 560–565. 10.1038/nature06269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg M., Bamps S., Soedling H., Hope I. A., Dolphin C. T. (2010). Escherichia coli MW005: lambda Red-mediated recombineering and copy-number induction of oriV-equipped constructs in a single host. BMC Biotechnol. 10:27. 10.1186/1472-6750-10-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler M., Bond P. L., Richardson D. J., Johnston A. W. B. (2005). A wide host-range metagenomic library from a waste water treatment plant yields a novel alcohol/aldehyde dehydrogenase. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 1917–1926. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00854.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild J., Hradecna Z., Szygbalski W. (2002). Conditionally amplifiable BACs: switching from single-copy to high-copy vectors and genomic clones. Genome Res. 12, 1434–1444. 10.1101/gr.130502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson L. L., Borlee B. R., Schloss P. D., Guan C., Allen H. K., Handelsman J. (2005). Intracellular screen to identify metagenomic clones that induce or inhibit a quorum-sensing biosensor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 6335–6344. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6335-6344.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung P. Y., Burke C., Lewis M., Egan S., Kjelleberg S., Thomas T. (2009). Phylogenetic screening of a bacterial, metagenomic library using homing endonuclease restriction and marker insertion. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:e144. 10.1093/nar/gkp746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., and Han W.-J. (2009). Gene cloning and characterization of a novel esterase from activated sludge metagenome. Microb. Cell Fact. 8:67. 10.1186/1475-2859-8-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Bruns M. A., Tiedje J. M. (1996). DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.