Abstract

Background

Excellent results have recently been reported for both total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), but there have been few reports about which has a better long-term outcome. The preoperative and postoperative results of TKA and UKA for osteoarthritis of the knee were thus compared.

Methods

The results of 48 patients who underwent TKA and 25 patients who underwent UKA were evaluated based on clinical scores and survivorship in the middle long-term period. Preoperative, latest postoperative, and changes in the femoro-tibial angle (FTA), range of motion (ROM), Japanese Orthopedic Association score (JOA score), and Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure (JKOM) were compared. The patients’ mean age was 73 years. The mean follow-up period was 9 years (TKA: mean, 10.5 years; range, 7–12 years; UKA: mean, 9 years; range, 6–11 years).

Results

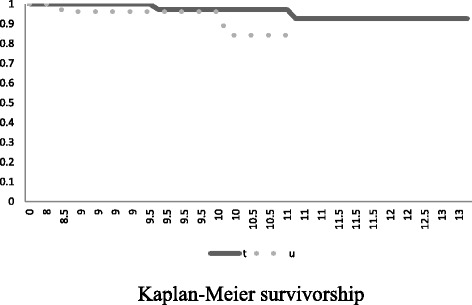

Preoperative FTA and ROM were significantly higher in the UKA group than in the TKA group. Total changes in all scores were similar among the two groups, as were changes in scores for all JOA and JKOM domains. The cumulative revision rate was higher for UKA than for TKA (7 versus 4 %). Kaplan-Meier survivorship at 10 years was 84 % for UKA and 92 % for TKA.

Conclusions

This clinical study found no significant differences between TKA and UKA, except in long-term survivorship.

Keywords: Clinical outcome, TKA, UKA

Background

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) have been recognized as good choices for the treatment of progressive osteoarthritis of the knee since these surgical procedures were first invented and reported [1, 2]. TKA has long been acknowledged as the best operative treatment for knee arthritis due to its durability and effectiveness in the recovery of knee function [3–6]. UKA has recently been established as a minimally invasive approach that preserves the bone and has excellent range of motion (ROM), less blood loss, and easier recovery of muscle damage [5]. Although UKA is reported to have poorer durability than TKA, there are many reports about its excellent clinical outcomes, which are not inferior to those of TKA.

To the best of our knowledge, few clinical studies and review articles have compared the long-term survivorship and clinical outcomes after TKA and UKA [7].

Methods

Patients who underwent knee joint arthroplasty between 2004 and 2007 with either a TKA (Stryker Scorpio NRG, Japan Stryker Company, Tokyo, Japan) or fixed-bearing UKA (Stryker EIUS UKA) were retrospectively identified from our database and reviewed. There were 48 patients with 50 primary TKAs and 25 patients with 28 UKAs performed at our institution. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments, and was approved by the local ethics committee. The exclusion criteria for UKA were more than 15° varus deformity, over 5° flexion contracture, less than 90° active ROM, dysfunction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), non-isolated medial compartment involving the patellofemoral joint, or rheumatoid arthritis [7–10]. Those who met any of the exclusion criteria for UKA underwent TKA. All patients with follow-up clinical data were enrolled in this trial, and the data were collected prospectively. The clinical analysis data included preoperative and postoperative femoro-tibial angle (FTA), ROM, Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) scores [11], and Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure (JKOM) [12]. The mean follow-up period was 9 years (TKA: mean, 10.5 years; range, 7–12 years; UKA: mean, 9 years; range, 6–11 years). Survivorship was defined as freedom from revision surgery. All TKAs were performed by the medial parapatellar approach, which induced eversion of the patella [13]. The UKA surgical procedure was a mini-invasive technique that involved a medial parapatellar approach with a 1-Qfb (Querfingerbreite, about 1.5 cm) incision from the upper pole of the patella to 1-Qfb distal to the medial tibial plateau by subluxation of the patella and exposure of the ACL [14]. All surgeries were performed by a single surgeon (H.K.). After the operation, patients were encouraged to undergo physiotherapy with mobilization and weight-bearing under the assistance and control of a physiotherapist. Clinical outcomes, such as FTA, ROM, and JOA scores, were assessed at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, and the latest follow-up. The clinical outcomes were then compared between the TKA and UKA groups. At every follow-up, a clinical and radiographic review was performed. Differences in sex distribution were assessed using the chi-square test. Differences in BMI, age, and follow-up time between TKA and UKA were evaluated using the chi-square test or non-matched pair analysis for two-group comparisons. All outcome measures (FTA, ROM, JOA score, JKOM) were evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively by the Mann-Whitney U test.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to assess implant durability. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Office Excel and Statcel 3 (OMS, Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

The mean age was not significantly different between the TKA group (72.2 ±7.9 years) and the UKA group (74 ± 6.4 years). The BMI was also not significantly different between the TKA group (25 ± 4.0 kg/m2) and the UKA group (24.1 ± 3.6 kg/m2) (Table 1). Preoperative and postoperative FTA and ROM were higher in the UKA group than in the TKA group. There were no differences between the preoperative and postoperative JOA scores and JKOM (Tables 2 and 3). The cumulative revision rate was higher for UKAs (7 %) than for TKAs (4 %; p = 0.469). The cause of revision was tibial implant sinking or infection (Table 4). Kaplan-Meier survivorship at 10 years was 92 % for TKA and 84 % for UKA (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Comparisons of variables in the TKA and UKA groups

| TKA group (n = 50) | UKA group (n = 28) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.2 ± 7.9 | 74 ± 6.4 | 0.060a |

| Sex (% female) | 80 | 90 | 0.550a |

| Height (cm) | 153 ± 4.2 | 150 ± 5.3 | 0.015b |

| Weight (kg) | 54.8 ± 8.9 | 50.2 ± 7.6 | 0.023b |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25 ± 4.0 | 24.1 ± 3.6 | 0.201b |

| Follow-up period (years) | 9 | 10.6 | 0.055a |

| Indication (primary osteoarthritis) | 40 | 20 | 0.607 a |

| Revision (number) | 2 | 2 | 0.469c |

aχ2 test

bStudent’s t test

cMantel-Haenszel procedure

Table 2.

Preoperative FTA, ROM, and JOA scores

| TKA group (n = 50) | UKA group (n = 28) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTA | 189.8 ± 7.9 | 180 ± 6.4 | 0.001 |

| ROM | 12.3–126.7 | 8.3–142 | 0.150 |

| JOA | 60.5 ± 4.2 | 66.5 ± 5.3 | 0.148 |

| JKOM | 50.1 ± 8.9 | 58.3 ± 7.6 | 0.238 |

Mann-Whitney U test

Table 3.

Postoperative FTA, ROM, and JOA scores

| TKA group (n = 50) | UKA group (n = 28) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTA | 175 ± 7.9 | 172.1 ± 6.4 | 0.200 |

| ROM | 3.3–126 | 4.2–142.5 | 0.015 |

| JOA | 81.1 ± 4.2 | 80.2 ± 5.3 | 0.98 |

| JKOM | 78.3 ± 10.4 | 83.6 ± 9.2 | 0.186 |

Mann-Whitney U test

Table 4.

Cases that required revision arthroplasty

| TKA | UKA | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 2 | 2 |

| FTA (average) | 175 | 170 |

| Cause of revision | ||

| Infection | 2 | |

| Aseptic loosening | 2 |

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survivorship comparison at 10 years between TKA and UKA. A significant difference exists in survivorship between TKA and UKA. t: TKA. u: UKA

Discussion

Recent studies have identified changes in scores as a measure of the effects of TKA and UKA [15, 16], and in this study, the focus was improvement in function with these procedures. The present study confirmed previous reports that UKA had significantly better postoperative outcome measures (FTA and ROM). These patients, however, also had higher preoperative scores, and it is the change in scores that determines the effect of the intervention. These results might be ascribed to the differences in knee joint contracture, osteoarthritic changes, and surgical invasion between the two groups. The changes in scores for all JOA and JKOM domains demonstrated no differences between the groups. If we consider the changes in scores, both surgical procedures are equally effective in improving function. However, it is important to recognize that there is a ceiling effect to scoring systems currently in use when evaluating patients with knee arthroplasty postoperatively [7].

Survival analysis is an accepted method of evaluating the durability of prostheses, and the prostheses showed survival rates of 92 % for TKA and 84 % for UKA. Although TKA is more frequently performed due to this perception, it is a more durable operation. Therefore, we assumed that clinical outcome scores for TKA and UKA would show similar excellent changes from preoperatively to postoperatively, and TKA would demonstrate better survivorship than UKA.

There were some limitations to this study. First, UKA and TKA cases were unevenly distributed, with the number of UKA cases being only about 60 % than that of TKA cases. It is reasonable to assume that surgeon proficiency could affect the outcome of UKA; however, surgeon-specific differences in outcomes were not identified. In our view, the present patient cohorts reflect the relative UKA/TKA usage in the general population undergoing knee arthroplasty.

Next, the ages of both patient groups were relatively older compared to other reports. Although some studies suggested that UKA had better absolute postoperative clinical outcomes, the average age of patients in those studies was within 70 years [17, 18]. In addition, the patients in those studies also had higher preoperative scores, which might imply high physical activity levels. In other words, the present patients had relatively low physical performance due to their age, and this may have affected the results for recovery of clinical outcome.

Finally, UKA demonstrated a higher failure rate but tended to have non-inferior function. About 10 % of the present UKA cases were revised, compared with 4 % for TKA. Early survival studies of UKA demonstrated revision rates of 15 to 28 % and midterm survivorship of 84 % to 98 %[19–21], while TKA has established survivorship of 92 to 100 % in long-term studies [1, 4–6, 16, 22–25]. As far as the present study is concerned, revision surgery was required due to sinking of the tibial implant, which might have been affected by overconcentration of loading because of overcorrection to an FTA of 170°. It has been suggested that surgeons should avoid cutting tibial bone stock too much and avoid overcorrection under 170° valgus because of the function of the ACL [26, 27]. Loss of tibial bone stock will lead to fragility and inability to sustain mechanical stress loading, and overcorrection of valgus might lead to ACL dysfunction as it is recognized as the stabilizer of knee alignment. In the present cases that required revision surgery, there may have been overcorrection (about 170°), which might have affected the function of the ACL and promoted overloading of the tibial implant, leading to its collapse.

In summary, consistent with the literature, patients with UKA had non-inferior clinical outcome scores for function preoperatively and postoperatively compared to patients with TKA. Changes in clinical outcome scores were similar among the two groups. The durability of both prostheses was assessed by survival analysis and showed that TKA was more durable.

Conclusion

There were no significant differences in outcomes between TKA and UKA, except for long-term survivorship, in the present study. This may suggest that both surgical procedures provide excellent results if we select patients carefully based on their age, activities, knee function, and degree of osteoarthritis.

Acknowledgements

The South Akita Orthopedic Clinic and Akita University Graduate School of Medicine supported this study. The authors would like to extend their appreciation to the patients in this study and thank Dr. Yusuke Sugimura and Dr. Yuji Kasukawa who assisted and supported our research.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AH and HK designed this study. AH analyzed the data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Aglietti P, Buzzi R, De Felice R, Giron F. The Insall-Burstein total knee replacement in osteoarthritis: a 10-year minimum follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:560–5. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewold S, Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Revision of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: outcome in 1,135 cases from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:469–74. doi: 10.3109/17453679808997780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colizza WA, Insall JN, Scuderi GR. The posterior stabilized total knee prosthesis: assessment of polyethylene damage and osteolysis after a ten-year-minimum follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1713–20. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199511000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diduch DR, Insall JN, Scott WN, Scuderi GR, Font-Rodriguez D. Total knee replacement in young, active patients: long-term follow-up and functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:575–82. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199704000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fetzer GB, Callaghan JJ, Templeton JE, Goetz DD, Sullivan PM, Kelley SS. Posterior cruciate-retaining modular total knee arthroplasty: a 9- to 12-year follow-up investigation. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:961–6. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.34824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Font-Rodriguez DE, Scuderi GR, Insall JN. Survivorship of cemented total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;345:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyons MC, MacDonald SJ, Somerville LE, Naudie DD, McCalden RW. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty database analysis: is there a winner? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:84–90. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruni D, Iacono I, Raspugli G, Zaffagnini S. Is unicompartmental arthroplasty an acceptable option for spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1442–51. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlueter-Brust K, Kugland K, Stein G, Henckel J, Christ H, Eysel P, et al. Ten year survivorship after cemented and uncemented medial uniglide unicompartmental knee arthroplasties. Knee. 2014;21:964–70. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li MG, Yao F, Joss B, Ioppolo J, Nivbrant B, Wood D. Mobile vs. fixed bearing unicondylar arthroplasty: a randomized study on short term clinical outcomes and knee kinematics. Knee. 2006;13:365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomihisa K. The therapy criteria of osteoarthritis of knee. Nippon Seikeigekagakkaisi. 1988;62:901–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akai M, Doi T, Fujino K, Iwaya T, Kurosawa H, Nasu T. An outcome measure for Japanese people with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheum. 2005;32:1524–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg AG. Surgical technique of posterior cruciate sacrificing, and preserving total knee arthroplasty in total knee arthroplasty. In: Rand JA, editor. Total Knee Arthroplasty. New York: Raven; 1993. pp. 115–153. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Insall J. Unicondylar knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;120:83–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDonald SJ, Charron KD, Bourne RB, Naudie DD, McCalden RW, Rorabeck CH. The John Insall Award. Gender-specific total knee replacement: prospectively collected clinical outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2612–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0430-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajgopal V, Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, MacDonald SJ, McCalden RW, Rorabeck CH. The impact of morbid obesity on patient outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:795–800. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin AK, Patton JT, Cook RE, Gaston M, Brenkel IJ. Unicompartmental or total knee arthroplasty? Results from a matched study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;451:101–6. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224052.01873.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isaac SM, Barker KL, Danial IN, Beard DJ, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Does arthroplasty type influence knee joint proprioception? A longitudinal prospective study comparing total and unicompartmental arthroplasty. Knee. 2007;14:212–7. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naudie D, Guerin J, Parker DA, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH. Medial unicompartment knee arthroplasty with the Miller-Galante prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1931–5. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman JH, Ackroyd CE, Shah NA. Unicompartmental or total knee replacement? Five-year results of a prospective randomized trial of 102 osteoarthritic knees with unicompartmental arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:862–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B5.8835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalury DD, Kelley TC, Adams MJ. Medial UKA: favorable mid-term results in middle-aged patients. J Knee Surg. 2013;26:133–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1322599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill GS, Joshi AB. Long-term results of kinematic condylar knee replacement: an analysis of 404 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;88:355–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B3.11288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating EM, Meding JB, Faris PM, Ritter MA. Long-term follow up of nonmodular knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:34–9. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsch TR, Kruger M, Moser MT, Geiger F. Follow-up of 11–16 years after modular fixed-bearing TKA. Int Orthop. 2009;33:431–5. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0543-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritter MA, Berend ME, Meding JB, Keating EM, Faris PM, Crites BM. Long-term follow up of anatomic graduated components posterior cruciate-retaining total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;388:51–7. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suggs JF, Li G, Park SE, Sultan PG, Rubash HE, Freigerg AA. Knee biomechanics after UKA and its relation to the ACL—a robotic investigation. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:588–94. doi: 10.1002/jor.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chassin EP, Mikosz RP, Andriacchi TP, Rosenberg AG. Function analysis of cemented unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:553–9. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(96)80109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]