Abstract

Lactulose is known to improve cognitive function in patients with early hepatic encephalopathy; however, the underlying mechanism remains poorly understood. In the present study, we investigated the behavioral and neurochemical effects of lactulose in a rat model of early hepatic encephalopathy induced by carbon tetrachloride. Immunohistochemistry showed that lactulose treatment promoted neurogenesis and increased the number of neurons and astrocytes in the hippocampus. Moreover, lactulose-treated rats showed shorter escape latencies than model rats in the Morris water maze, indicating that lactulose improved the cognitive impairments caused by hepatic encephalopathy. The present findings suggest that lactulose effectively improves cognitive function by enhancing neuroplasticity in a rat model of early hepatic encephalopathy.

Keywords: nerve regeneration, brain injury, hepatic encephalopathy, lactulose, neuroplasticity, neurogenesis, Morris water maze, cognition, rats, neuronal nuclei, glial fibrillary acidic protein, NSFC grants, neural regeneration

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy is a common complication of chronic liver disease, and is associated with a poor prognosis. It manifests clinically as a spectrum of neuropsychiatric disturbances encompassing cognitive, intellectual, motor, and psychomotor functions, from subtle changes in personality or sleep-wake cycle to major disturbances in cognitive function, motor activity and coordination (Ferenci et al., 2002; Gorg et al., 2010). Hepatic encephalopathy is least severe in its early stages, with few recognizable clinical symptoms other than mild cognitive and psychomotor deficits. Nevertheless, early hepatic encephalopathy impairs a patient's ability to perform certain tasks, such as driving, and reduces their quality of life, in addition to predisposing to full hepatic encephalopathy and reducing the patient's lifespan, making early hepatic encephalopathy a serious health, social and economic burden. Early diagnosis and treatment initiation would improve patients’ quality of life and prevent the progression of neurological impairments (Felipo, 2013).

Blood levels of ammonia are often elevated in patients with hepatic encephalopathy, so current therapies are based on lowering ammonia. Non-absorbable disaccharides are the first-line drug treatment for lowering the production and absorption of ammonia (Riordan and Williams, 1997; Blei and Cordoba, 2001). Lactulose, a synthetic disaccharide, is the most commonly used non-absorbable disaccharide in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy (Sharma et al., 2013; Sharma and Sharma, 2013; Ziada et al., 2013). It comprises the monosaccharides lactose and galactose, and is administered as syrup. Doses are generally titrated to achieve two to four semi-soft stools daily, with typical doses of 20 g/30 mL orally three to four times per day. Lactulose significantly improves cognition in patients with early hepatic encephalopathy (Prasad et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2011).

Neuroplasticity can be defined as the ability of the nervous system to respond to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, function and connections. The process is essential to normal cognitive function and is widely implicated in disease processes (McEwen, 2006). Neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus contributes significantly to central neuroplasticity mechanisms such as long-term potentiation, learning and memory (Massa et al., 2011). Additionally, astrocytes have the ability to eliminate ammonia, and play an important role in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy (Lockwood et al., 1991; Haussinger et al., 2000).

Lactulose is known to improve cognitive impairment; however, few studies have addressed its effect on neuroplasticity. Here, we observed the effect of lactulose treatment on behavior and cognitive function in a rat model of early hepatic encephalopathy, and investigated its effects on neuroplasticity to elucidate the mechanisms underlying its cognition enhancing effects.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Thirty adult male Wistar rats, initially weighing 240.38 ± 1.79 g, were supplied by Peking University Health Science Animal Center (Beijing, China; license No. SCXK (Jing) 2007-0001). The rats were housed in polypropylene cages in a temperature (22 ± 1°C) and humidity (60 ± 10%) controlled environment, under a 12-hour light-dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m.). The animals had free access to food and water throughout the experiments. Animal maintenance and experimental protocols were carried out in accordance with guidelines approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences in China.

Animal grouping and early hepatic encephalopathy model establishment

The rats were randomly divided into three groups: control, model and lactulose (n = 10 rats per group). To induce hepatic encephalopathy, rats in the model and lactulose groups received a mixture of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and olive oil (1:1 v/v; National Pharmaceutical Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) at a dose of 1 mL/kg by gavage, in the morning, twice a week (Mondays and Thursdays) for 12 weeks (Tsai et al., 2009). Control animals received normal saline. Animals in the lactulose group also received intragastric lactulose (Solvay Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Brussels, Belgium), 6 g/kg, in the afternoon, five times a week (Monday to Friday) for 12 weeks (Ferenci et al., 2002).

Morris water maze

Hepatic encephalopathy rats were evaluated for spatial learning and memory capabilities using a Morris water maze as described previously (Ji et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012). Two training trials a day were conducted on 3 consecutive days during the 8th week. The experimental apparatus consisted of a cylindrical water tank (145 cm diameter, 60 cm high) filled with water maintained at 21 ± 1°C. The water was made opaque with black ink. A platform (10 cm in diameter) was submerged 2 cm below the water surface and placed at the midpoint of one quadrant. Room lights illuminated the pool, and visual cues around the room (window, cabinets, furniture) were kept consistent. A video camera was placed above the center of the pool and connected to a video tracking system. During each training session, the rats were placed in the pool at a specified starting position and allowed to swim freely until they found the platform. The time required to escape (escape latency) was recorded. Rats that found the platform within 120 seconds were allowed to remain on it for 20 seconds and were then returned to the home cage. If a rat did not reach the platform within 120 seconds, it was gently guided there by the experimenter, and allowed to stay on it for 20 seconds. The test was performed again at 12 weeks to assess spatial cognitive function.

5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) injection

After completion of the Morris water maze test, neurogenesis was studied in the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus. BrdU (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl at 20 mg/mL. Four rats in each group each received three intraperitoneal injections of BrdU (50 mg/kg) at 12 hour intervals (total dose of 2.5 mL/kg) and were sacrificed 24 hours after the last injection (Stefovska et al., 2008). The brains were prepared for immunohistochemical staining with BrdU, described below.

Tissue processing and blood sampling

Body weight was monitored weekly. After completion of the behavioral tests, six rats in each group were decapitated and blood samples were collected for analysis of serum levels of ammonia, and activities of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase. Brains were immediately removed and washed in ice-cold isotonic saline. The remaining rats were anesthetized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). The brains were removed and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C, and cryoprotected in a graded sucrose series (15%, 20% and 30% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS) at 4°C. Coronal sections (35 μm thick) were cut using a cryostat.

Liver tissues were taken from the left lobe of the liver of each rat, fixed in 15% buffered paraformaldehyde, and dehydrated through a graded alcohol series. Specimens were embedded in paraffin blocks, cut into 5 μm thick sections and placed on glass slides, before staining with hematoxylin-eosin to assess liver damage (Yang et al., 2010). Fibrosis was graded (Scheuer, 1991) by a pathologist blinded to experimental grouping.

Serum levels of ammonia, and alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase activities, were measured using commercially available kits (Jiancheng Biotechnology Institute, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Brain immunohistochemistry

For BrdU immunohistochemistry, free-floating brain sections (35 μm thick) were incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody solution containing mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (1:100; Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). Sections were then washed in PBS and incubated in secondary antibody solution containing biotinylated goat polyclonal anti-mouse antibody I (SP immunohistochemical staining kit, Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed as before, and incubated in horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin solution for 30 minutes at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was visualized using 0.2% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) in PBS containing 0.025% hydrogen peroxide for approximately 5 minutes, and washed in PBS. The sections were mounted and dried (Ngwenya et al., 2005), and viewed under an optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan, 400× magnification). BrdU-labeled cells in the subgranular zone were counted in every 10th section, and multiplied by 10 to estimate the total number of BrdU-labeled cells.

For immunohistochemistry of neuronal nuclei (NeuN) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), free-floating brain sections (35 μm thick) were incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibody solution containing mouse monoclonal anti-NeuN (1:50; Chemicon) or rabbit anti-GFAP (1:50; Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Sections were washed in PBS, then incubated in secondary antibody solution containing biotinylated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody I (SP immunohistochemical staining kit, Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 30 minutes at room temperature. The sections were washed again and incubated in horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin solution for 30 minutes at room temperature, before visualization with 0.2% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) in PBS containing 0.025% hydrogen peroxide for approximately 5 minutes. The sections were washed in PBS, mounted on slides, dried, dehydrated through a graded alcohol series, cleared with xylene, and coverslipped using Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

For NeuN immunostaining, the number of immunoreactive cells in the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cell layer were evaluated under a light microscope at a magnification of 400 × with the investigator blinded to the experimental grouping. Every 10th section was quantified and the immunopositive neurons were expressed as the mean number of cells per mm2. For GFAP immunostaining of the CA1, the number of immunoreactive cells of the stratum oriens, stratum pyramidale, and stratum radiatum were analyzed as described for NeuN staining (Liu et al., 2011).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM and analyzed statistically using one-way analysis of variance with SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). After testing for homogeneity of variances, Tukey's multiple comparisons method was performed to identify differences between experimental groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Quantitative analysis of experimental animals

Thirty rats were randomly assigned to the control, model and lactulose groups (n = 10 per group). No infections were observed during the experimental period, but two rats in the model group died from serious liver damage during the 7th week. Their data were excluded from the final statistical analysis.

Effect of lactulose treatment on neuroplasticity in rats with CCl4-induced hepatic encephalopathy

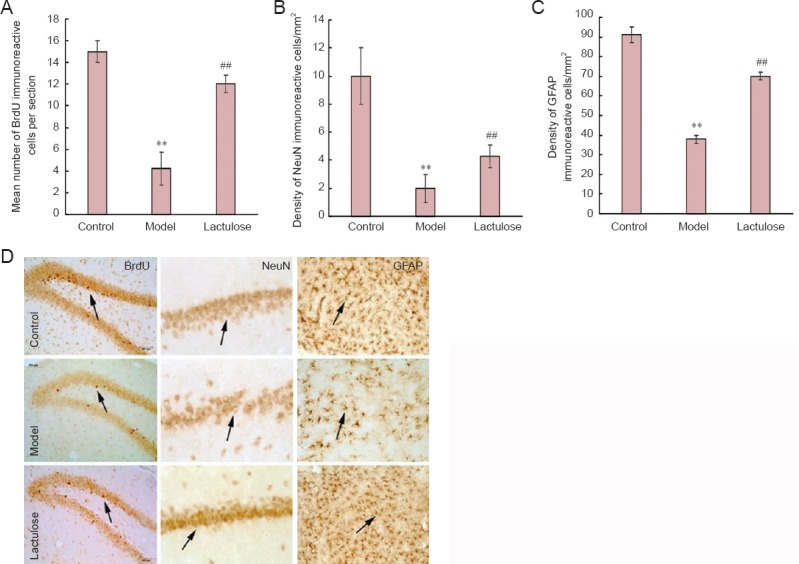

Neurogenesis was examined by quantifying BrdU-immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus (Figure 1A, D). NeuN and GFAP immunoreactivity was used to identify functional neurons in the CA1 (Figure 1B, D) and astrocytes in the dentate gyrus (Figure 1C, D), respectively.

Figure 1.

Effects of lactulose administration on neurogenesis and on numbers of neurons and astrocytes in the hippocampus of rats with hepatic encephalopathy (imunohistochemical staining).

(A) Number of BrdU-immunoreactive cells per section. (B) Density of NeuN-immunoreactive cells/mm2. (C) Density of GFAP-immunoreactive cells/mm2. (D) Representative immunomicrographs of BrdU-(dentate gyrus), NeuN-(CA1) and GFAP-(dentate gyrus) positive cells (arrows). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 rats per group). **P < 0.01, vs. control group; ##P < 0.01, vs. model group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test). BrdU: 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine; NeuN: neuronal nuclei; GFAP: glial fibrillary acidic protein.

There were significantly fewer BrdU-, NeuN- and GFAP- immunoreactive cells in the model group than in the control group (P < 0.01), and significantly more of all three cell types in the lactulose group compared with the model group (P < 0.01). This suggests that lactulose reversed hepatic encephalopathy-induced cellular alterations.

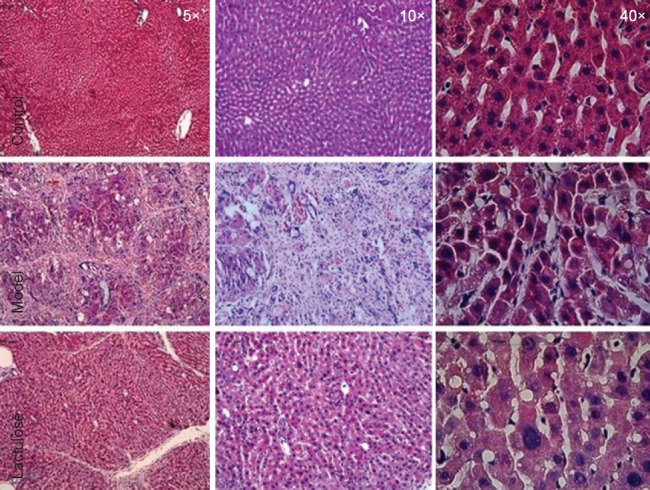

Effect of lactulose treatment on liver histology in rats with CCl4-induced hepatic encephalopathy

In the model group, fibrous tissue substituted most of the portal areas in the liver, and some portal areas were connected to central veins. Moreover, hepatocyte clusters were completely surrounded by fibrous tissue, producing cirrhotic nodules. Livers from lactulose-treated animals had less severe pathology than model animals, indicating that lactulose ameliorated the liver damage induced by CCl4 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of lactulose treatment on liver histology in rats with hepatic encephalopathy.

Liver sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (n = 4–5 rats per group). Severe hepatic cirrhosis was observed in the model group, whereas none was seen in the control group. Lactulose-treated model rats showed less cirrhosis than model rats.

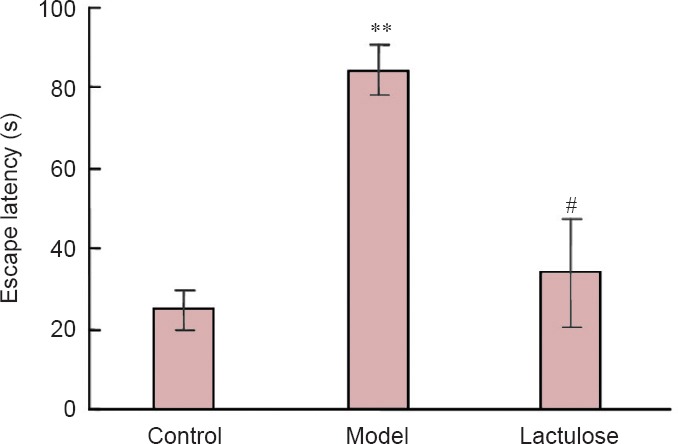

Effect of lactulose treatment on spatial cognitive function in rats with CCl4-induced hepatic encephalopathy

The Morris water maze test is widely used to measure cognitive deficits in rodent models of neurological disorders. Model rats took notably longer than control rats to find the hidden platform (P < 0.01), indicating that spatial reference memory was impaired in rats with CCl4-induced hepatic encephalopathy. Rats that received lactulose had significantly shorter escape latencies than model rats (P < 0.01), suggesting that lactulose alleviated the spatial memory deficits induced by CCl4 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of lactulose treatment on escape latency of rats with hepatic encephalopathy in the Morris water maze 12 weeks after receiving carbon tetrachloride.

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 10 per group). **P < 0.01, vs. control group; ##P < 0.01, vs. model group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test).

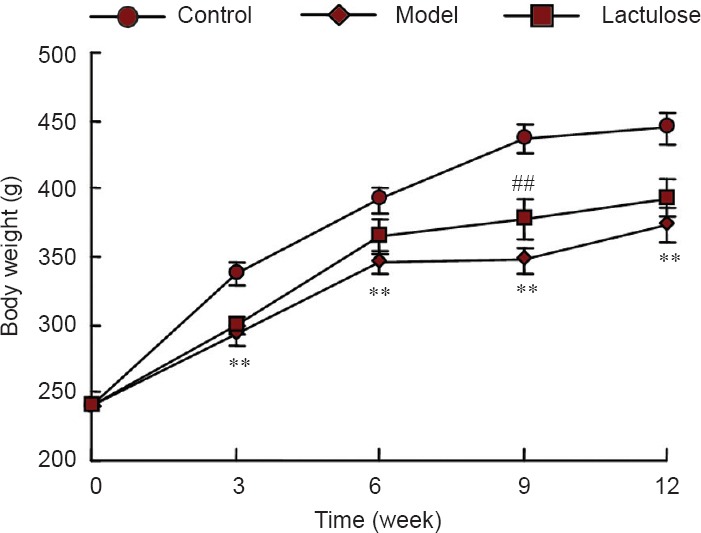

Effect of lactulose treatment on body weight of rats with CCl4-induced hepatic encephalopathy

Weight loss and cachexia are commonly observed in patients with hepatic encephalopathy (Lockwood et al., 1986). Ammonia stimulation of the hypothalamic satiety centers may suppress appetite, leading to cachexia. We therefore monitored body weight throughout the experimental period (Figure 4). By 3 weeks, the model rats had notably lower body weights than controls (P < 0.01), and lactulose-treated animals weighed significantly more than rats in the model group (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Effects of lactulose treatment on body weight of rats with hepatic encephalopathy.

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 8–10 rats per group). **P < 0.01, vs. control group; ##P < 0.01, vs. model group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test).

Effect of lactulose treatment on the serological parameters of rats with CCl4-induced hepatic encephalopathy

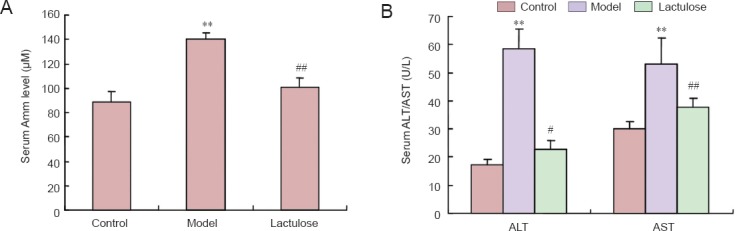

To investigate the protective effects of lactulose on liver function, we measured serum ammonia level, and alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase activities. All three parameters were significantly elevated in the model group (P < 0.01), indicative of severe liver damage. However, rats in the lactulose group had lower serum ammonia (P < 0.01) (Figure 5A), alanine aminotransferase activity (P < 0.05) and aspartate aminotransferase activity (P < 0.01) than the model rats (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of lactulose treatment on serological parameters in rats with carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic encephalopathy.

(A) Serum ammonia (Amm) level; (B) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5–6 rats per group). **P < 0.01, vs. control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. model group (one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test).

Discussion

Most patients with cirrhosis will develop early hepatic encephalopathy, which severely affects cognitive ability, day-to-day functioning, and quality of life. The condition is always related to increased mortality and places great demands on the healthcare system. The pathophysiology of the disorder remains poorly understood, meaning that treatment choices are limited. Ammonia is known to have a central role in the development of hepatic encephalopathy, so non-absorbable disaccharides, such as lactulose and lactitol, are the most commonly used pharmacological treatments.

Various experimental approaches, such as the Morris water maze in rodent hepatic encephalopathy models, have been adopted to investigate the neurocognitive effects of hepatic encephalopathy (Ortiz et al., 2006; Mendez et al., 2008). In the present study, hepatic encephalopathy model rats took significantly longer time to find the hidden platform than control rats. Lactulose treatment improved this deficit in cognitive function, consistent with results obtained from clinical trials of lactulose in patients with early hepatic encephalopathy (Prasad et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2011).

Neuroplasticity plays a significant role in cognitive function. Exploring changes in neuroplasticity can enhance our understanding of disease pathogenesis and improve treatment strategies. One component of neuroplasticity is neurogenesis. Adult neurogenesis predominantly occurs in two restricted regions: the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus, and the subventricular zone (Cheung et al., 2007; Molnar, 2011). Newborn cells in the subgranular zone differentiate into neuronal cells and establish synaptic connections with neighboring cells (Zhao et al., 2008). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis plays a critical role in synaptic plasticity processes such as long-term potentiation and learning and memory (Massa et al., 2011). To date, there have been few studies investigating the effect of hepatic encephalopathy on neurogenesis. In the present study, we used BrdU staining to assess the effect of lactulose on hippocampal neurogenesis. BrdU is a thymidine analog that becomes incorporated into the DNA of dividing cells during the S-phase of the cell cycle, and as such is widely used to measure cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain, including in humans (Taupin, 2007). Our results suggest that lactulose increases the number of new neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. It should be noted that BrdU was injected 24 hours before animals being sacrificed in present study, because we intended to assess the proliferation of neural stem cells. In future study, the differentiation of neural stem cells should be taken into consideration by using double-label technique for BrdU and GFAP/NeuN.

Chastre et al. (2010) found that ammonia and pro-inflammatory mediators reduced GFAP expression. Previous studies revealed that GFAP mRNA and protein expression were significantly reduced in animal models of acute liver failure (Belanger et al., 2002) and in cultured astrocytes exposed to ammonia (Norenberg et al., 1990), confirming the important role of astrocytes in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy and consequences for neuronal function. Astrocytes eliminate ammonia by converting glutamate to glutamine by amidation, catalyzed by glutamine synthetase (Lockwood et al., 1991; Haussinger et al., 2000). In the present study, lactulose elevated the number of GFAP-immunoreactive cells, which may mediate its neuroprotective effect.

Mounting evidence suggests that lactulose is neuroprotective. Chen et al. (2012) proposed that bacterial fermentation in the gastrointestinal tract can produce considerable amounts of hydrogen from lactulose, which was used to explain the protective effect of lactulose for ischemic stroke. Our data supports this hypothesis, strongly suggesting that lactulose treatment improves neuroplasticity by enhancing neurogenesis and increasing the number of astrocytes and neurons, effectively restoring learning ability in rat models of hepatic encephalopathy.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 30873390.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Copyedited by Murphy JS, Norman C, Wang J, Yang Y, Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- Belanger M, Desjardins P, Chatauret N, Butterworth RF. Loss of expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein in acute hyperammonemia. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blei AT, Cordoba J. Hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1968–1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastre A, Jiang W, Desjardins P, Butterworth RF. Ammonia and proinflammatory cytokines modify expression of genes coding for astrocytic proteins implicated in brain edema in acute liver failure. Metab Brain Dis. 2010;25:17–21. doi: 10.1007/s11011-010-9185-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhai X, Kang ZM, Sun XJ. Lactulose: an effective preventive and therapeutic option for ischemic stroke by production of hydrogen. Med Gas Res. 2012;2:3. doi: 10.1186/2045-9912-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AF, Pollen AA, Tavare A, DeProto J, Molnar Z. Comparative aspects of cortical neurogenesis in vertebrates. J Anat. 2007;211:164–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felipo V. Hepatic encephalopathy: effects of liver failure on brain function. Nat Neurosci Rev. 2013;14:851–858. doi: 10.1038/nrn3587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felipo V, Butterworth RF. Neurobiology of ammonia. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;67:259–279. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy-definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11 th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716–721. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorg B, Qvartskhava N, Bidmon HJ, Palomero-Gallagher N, Kircheis G, Zilles K, Haussinger D. Oxidative stress markers in the brain of patients with cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2010;52:256–265. doi: 10.1002/hep.23656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haüssinger D, Kircheis G, Fischer R, Schliess F, vom Dahl S. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver desease: a clinical manifestation of astrocyte swelling and low grade cerebral edema. J Hepatol. 2000;32:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C, Li Q, Aisa H, Yang N, Dong YL, Liu YY, Wang T, Hao Q, Zhu HB, Zuo PP. Gossypium herbaceam extracts attenuate ibotenic acid-induced excitotoxicity in rat hippocampus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:331–339. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Yang N, Hao W, Zhao Q, Ying T, Liu S, Li Q, Liang Y, Wang T, Dong Y, Ji C, Zuo P. Dynamic proteomic analysis of protein expression profiles in whole brain of Balb/C mice subjected to unpredictable chronic mild stress: implications for depressive disorders and future therapies. Neurochem Int. 2011;58:904–913. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Aisa HA, Ji C, Yang N, Zhu H, Zuo P. Effects of Gossypium herbaceam extract administration on the learning and memory function in the naturally aged rats: neuronal niche improvement. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:101–111. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood A, Yap E, Wong W. Cerebral ammonia metabolism in patients with severe liver disease and minimal hepatic encephalopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:337–341. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood AH, Ginsberg MD, Rhoades HM, Gutierrez MT. Cerebral glucose metabolism after portacaval shunting in the rat. Patterns of metabolism and implications for the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:86–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI112578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Li L, Lu CZ, Cao WK. Clinical efficacy and safety of lactulose for minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:1250–1257. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834d1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa F, Koehl M, Wiesner T, Grosjean N, Revest JM, Piazza PV, Abrous DN, Oliet SH. Conditional reduction of adult neurogenesis impairs bidirectional hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6644–6649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016928108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: central role of the brain. Dialog Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:367–381. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.4/bmcewen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez M, Mendez-Lopez M, Lopez L, Aller MA, Arias J, Cimadevilla JM, Arias JL. Spatial memory alterations in three models of hepatic encephalopathy. Behav Brain Res. 2008;188:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar Z. Evolution of cerebral cortical development. Brain Behav Evol. 2011;78:94–107. doi: 10.1159/000327325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary JT, Whittemore SR, Zhu Q, Norenberg MD. Destabilization of glial fibrillary acidic protein mRNA in astrocytes by ammonia and protection by extracellular ATP. J Neurochem. 1994;63:2021–2027. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwenya LB, Peters A, Rosene DL. Light and electron microscopic immunohistochemical detection of bromodeoxyuridine-labeled cells in the brain: different fixation and processing protocols. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:821–832. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6605.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD, Neary JT, Norenberg LO, McCarthy M. Ammonia induced decrease in glial fibrillary acidic protein in cultured astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1990;49:399–405. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz M, Cordoba J, Jacas C, Flavia M, Esteban R, Guardia J. Neuropsychological abnormalities in cirrhosis include learning impairment. J Hepatol. 2006;44:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S, Dhiman RK, Duseja A, Chawla YK, Sharma A, Agarwal R. Lactulose improves cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis who have minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:549–559. doi: 10.1002/hep.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan SM, Williams R. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:473–479. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708143370707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: a need for reassessment. J Hepatol. 1991;13:372–374. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90084-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma BC, Sharma P, Lunia MK, Srivastava S, Goyal R, Sarin SK. A randomized, double-blind controlled trial comparing rifaximin plus lactulose with lactulose alone in treatment of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Sharma BC. Disaccharides in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2013;28:313–320. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9392-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefovska VG, Uckermann O, Czuczwar M, Smitka M, Czuczwar P, Kis J, Kaindl AM, Turski L, Turski WA, Ikonomidou C. Sedative and anticonvulsant drugs suppress postnatal neurogenesis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:434–345. doi: 10.1002/ana.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupin P. BrdU immunohistochemistry for studying adult neurogenesis: Paradigms, pitfalls, limitations, and validation. Brain Res Rev. 2007;53:198–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai PC, Fu TW, Chen YM, Ko TL, Chen TH, Shih YH, Hung SC, Fu YS. The therapeutic potential of human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells from Wharton's jelly in the treatment of rat liver fibrosis. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:484–495. doi: 10.1002/lt.21715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang FR, Fang BW, Lou JS. Effects of Haobie Yangyin Ruanjian decoction on hepatic fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1458–1464. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132:645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziada DH, Soliman HH, El YSA, Hamisa MF, Hasan AM. Can Lactobacillus acidophilus improve minimal hepatic encephalopathy?. A neurometabolite study using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2013;14:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]