Abstract

Over the last two decades, the concept of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) has been proposed as an alternate path in the natural history of decompensated cirrhosis. ACLF is thus characterized by the presence of a precipitating event (identified or unidentified) in subjects with underlying chronic liver disease leading to rapid progression of liver injury and ending in multi-organ dysfunction characterized by high short term mortality. Multiple organ failure and increased risk for mortality are key to diagnosis of ACLF. The prevalence of ACLF ranges from 24–40% in hospitalized patients. The pathophysiological basis of ACLF can be explained using a 4 part model of predisposing event, injury due to precipitating event, response to injury and organ failure. Though several mathematical scores have been proposed for identifying outcomes with ACLF, it is yet unclear whether these organ failure scores are truly prognostic or are only reflective of the dying process. Treatment paradigms continue to evolve but consist of early recognition, supportive intensive care, and consideration of liver transplantation prior to onset of irreversible multiple organ failure.

INTRODUCTION

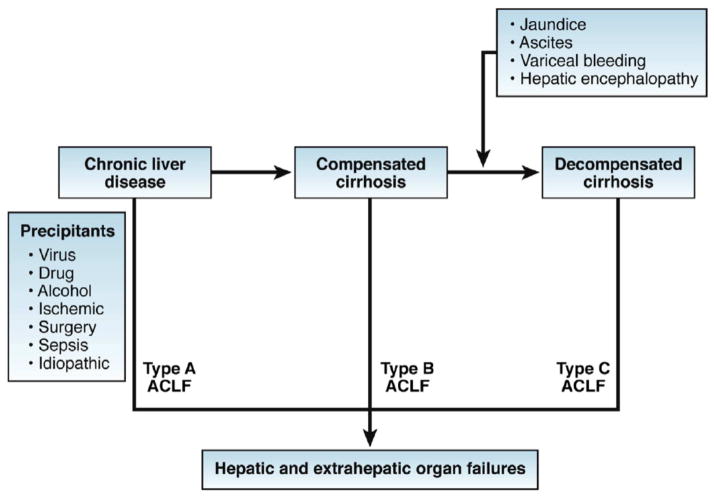

For years, a dichotomous fate had been assigned to persons with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis: period of stable compensated liver disease followed by progression to decompensated liver disease towards eventual death in the absence of liver transplantation (LT). Decompensation was heralded by the onset of ascites, jaundice, variceal bleeding, or hepatic encephalopathy with a median survival of two years. There was no term to describe the events between decompensated cirrhosis and multiple organ failure that these patients eventually died of. Over the last two decades, the concept of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) has been proposed as an alternate path in the natural history of decompensated cirrhosis. Multiple organ failure and increased risk for mortality are key to diagnosis of ACLF. It is now recognized that patients with compensated cirrhosis and patients with chronic liver disease without cirrhosis may also develop multiple organ failure and are included among ACLF. The purpose of the review is to update our current understanding of ACLF (definitions and pathophysiology), characterize associated extra-hepatic organ dysfunction, identify current prognostic markers and predictive models, and describe potential therapies.

DEFINITION

As compared to the general population, persons with compensated cirrhosis have a five-fold (hazard ratio, HR=4.7, 95% confidence interval, CI 4.4–5.0) and persons with decompensated cirrhosis have a 10-fold (HR=9.7, 95% CI 8.9–10.6) increased risk of death.1 In a recent population based study of Danish alcoholic cirrhotics, the median 1 year survival was 83% in persons with compensated cirrhosis and between 36–80% for persons with decompensated cirrhosis.2 The underlying premise of defining ACLF is to identify a subset of patients with either chronic liver disease or cirrhosis that have an unexpected rapid and abrupt decompensation of hepatic function with extrahepatic organ failure. There is an elevated risk of short term mortality similar to persons with acute liver failure (ALF) and substantially higher than expected with the natural progression of cirrhosis with chronic decompensation.3 In a recent study, cirrhotics with ACLF had 90 day mortality rates of 34% versus 1.9% for chronic decompensation. ACLF is characterized by a “paralysis of immune response” akin to changes seen amongst persons with severe sepsis.4 This is in contradistinction to ALF which is characterized by onset of coagulopathy and encephalopathy within 8 weeks in subjects without underlying chronic liver disease.5 Cerebral edema may be encountered in ACLF, but is rarely seen in decompensated cirrhosis without ACLF.

Three separate definitions have been derived from multicenter efforts from the Asia-Pacific Region, European as well as North American groups.3, 6–9 (Table 1) It must be recognized that the characterization of each organ failure was different between the separate consortium definitions. In addition, the timing of precipitating injury, importance placed on extra hepatic organ failure, especially infection, and definition of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis were different across the three iterations. In order to consolidate the complementary definitions, a framework was proposed by a working group on behalf of the World Gastroenterology Organization. 3 According to this consensus, ACLF is a “syndrome in patients with chronic liver disease with or without previously diagnosed cirrhosis which is characterized by acute hepatic decompensation resulting in liver failure (jaundice and prolongation of the INR [International Normalized Ratio]) and one or more extrahepatic organ failures that is associated with increased mortality within a period of 28 days and up to 3 months from it.” Further ACLF is classified based on whether in occurs in patients without cirrhosis (type A, e.g. reactivation of hepatitis B), in persons with compensated cirrhosis (type B, e.g. acute alcoholic hepatitis in patient with cirrhosis) or in those with a history of prior hepatic decompensation (type C, e.g. infection in patient with history of ascites) (Figure 1).10–12 Since organ failure is required for defining ACLF, the diagnosis of ACLF may currently be made at a time point that the process is largely irreversible. Therefore, a definition that takes into consideration prognostic factors other than organ failure is required to allow early diagnosis and treatment of ACLF.

Table 1.

Definitions of acute on chronic liver failure

| Study | ACLF | Components | Survival | Common regional precipitants and underlying disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NASCELD Infection related ACLF |

≥2 extra- hepatic organ failures | shock, grade 3 or 4 hepatic encephalopathy, need for dialysis, or need for mechanical ventilation | 30 day mortality: 27% (1), 49% (2), 64% (3), and 77% (4) extra- hepatic organ failures | Bacterial infection, 16% with nosocomial infection Varied etiology of underlying liver disese: |

| European Association for the Study of the Liver- Chronic Liver Failure consortium (EASL- CLIF) Consortium | hepatic or extra-hepatic organ failure with >15% 28- day mortality | Grade 1 (1) patients with single kidney failure; (2) patients with kidney dysfunction (1.5–1.9 mg/dL) and or mild to moderate hepatic encephalopathy along with single failure of liver, coagulation, circulation or respiration; (3) patients with hepatic encephalopathy along with kidney dysfunction (1.5–1.9 mg/dL). Grade 2: 2 or more failures Grade 3: 3 or more organ failures. | 28-day mortality 22%, 32%, and 77% | Bacterial infection Underlying liver disease: alcoholic liver disease and HCV |

| Asia Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) | acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice (bilirubin >5mg/dL) and coagulopathy (INR >1.5) complicated within 4 weeks of onset by ascites and/or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease | Liver failure | Reactivation of hepatitis B, superinfection with hepatitis E Underlying liver disease: Hepatitis B; alcoholic cirrhosis; Hepatotoxic drugs |

Figure 1.

Proposed types of ACLF (from Jalan et al. Ref 3)

Proposed unifying pathogenesis for different types of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF).

PREVALENCE AND NATURAL HISTORY

The prevalence of ACLF is hard to assess given variation in definitions of ACLF. In the European multicenter study, the prevalence among hospitalized cirrhotics was 31%.6 In the North American experience, the prevalence of infection associated ACLF (>2 associated organ failures) was approximately 24.3%.9 Similarly, in a European population based cirrhotic cohort (2001–2010), the prevalence of infection-related ACLF was 24%.13 In a single center prospective nationwide inception cohort study in Italy, ACLF was observed in 12% of hospitalized cirrhotics.14 In another study, ACLF developed in 40% at 5 years for persons with cirrhosis.15

Limited data exists on the natural history of ACLF. Using follow up data from the CLIF consortium, of 388 patients, about 50% had resolution or improvement in their ACLF, 20% worsened and 30% had a steady or fluctuating course. The prognosis was best in patients with grade 1 ACLF (discussed later) with the highest resolution in grade 1 ACLF (resolution 54.5%) as compared to ACLF grade 3 (16%). 10 The time course assessing improvement, resolution or worsening could be determined within 48 hours in 40%, 3–7 days in 15%, and 8–28 days in another 15% of the population. Long term outcomes may also be different based on the precipitating factor. In a single center study of 405 patients with ACLF from China, subjects with hepatic insults (e.g. viral hepatitis, hepatotoxic drugs) as compared to extra hepatic insults (e.g. bacterial infection or surgery) had similar short term mortality (48.3% vs. 50.7% 28 day transplant free mortality) but lower 1 year mortality (63.9% vs. 74.6%, p<0.02).8 There were also differences is predictors of poor prognosis such as presence of multi-organ failure being more predictive of deaths in subjects with extra-hepatic precipitants rather than hepatic related insults.

ETIOLOGY

There are also differences in etiologies of ACLF based on the region of the world. Reactivation of hepatitis B and superimposition of acute hepatitis A or hepatitis E on chronic liver disease are important causes of ALF as well as ACLF in Asia. Alcoholic hepatitis and infections are reportedly more common in western centers, but do contribute to a significant proportion of patients with ACLF in the East too. Given that about half of subjects with cirrhosis admitted have evidence of infection or sepsis and a further 25% develop nosocomial infections with high inpatient hospital mortality, infection plays an overwhelming role in the natural history of ACLF.

COSTS

Unfortunately, there are sparse data on the cost of ACLF as it is often hard to parse out hospital level data and accurately identify subjects with ACLF versus non ACLF related decompensated liver disease. In one estimate of the nationwide inpatient sample in the United States, the mean cost per ACLF hospitalization was twice as high as that for patients with cirrhosis without ACLF (approximately $32,000 for ACLF, compared to $16,000 for cirrhosis without ACLF).16

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

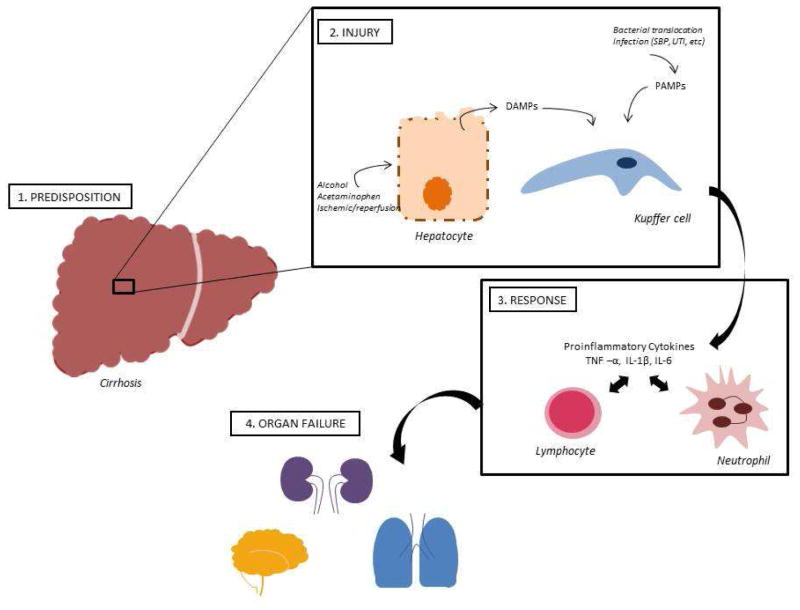

Borrowing from the sepsis literature, Jalan and colleagues described the pathophysiological basis of ACLF using a 4 part model of predisposing event, injury due to precipitating event, response to injury and organ failure.10–12, 17, 18 (Figure 2). In their model, predisposition refers to underlying cirrhosis and concomitant illnesses. Injury may be due to one of many insults such as alcoholic hepatitis, superimposed viral hepatitis, reactivation of hepatitis B, gastrointestinal bleeding (variceal or non variceal), drug induced liver injury, ischemia, and surgery. The prevalence of identified bacterial infection is higher among persons with ACLF as compared to those without ACLF.6 Precipitating injury may be unknown in about half of the cases. The inflammatory response is important with a robust response as judged by presence of elevated C reactive protein (CRP) or an elevated leukocyte count associated with worse outcomes. It is unclear whether the inflammation is a response to the inciting event or a part of the inciting event. It is also likely that the compensatory anti-inflammatory response is important in determining the risk for nosocomial infection and the higher risk of mortality.19 Organ failure is the last component with increasing numbers of organ failures (i.e. hemodynamic collapse, renal failure, pulmonary compromise, liver failure) portending poor outcomes especially in the setting of chronic liver disease.

Figure 2.

Pathophysiology of ACLF (see attached figure)

In normal conditions, the liver exerts an important defensive role against pathogens and related antigens. The liver resident-macrophages, i.e. Kupffer cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells act as first-line defense mechanisms against gut-derived toxins and bacteria. Kupffer cells are present within the lumen of the hepatic sinusoids and exert potent phagocytic activity.20 Upon activation of Kupffer cells, there is significant release of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-17, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor-alpha) which induces leukocyte recruitment and oxidative stress, as well as complement activation. Both Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells also have antigen presenting capabilities, through expression of MHC class I and II.

In cirrhosis, there is loss or damage of Kupffer cells, due to sinusoidal fibrosis and capillarization, portosystemic shunt formation and impaired hepatic synthesis of complement proteins and soluble pattern recognition receptors. In addition, compromise of circulating immune cell function has been demonstrated in cirrhosis 21. Patients with ACLF demonstrate significant cellular immune depression, as measured by reduced ex vivo TNF-α production and monocyte HLA-DR expression after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. This effect is significantly more pronounced in ACLF patients compared to those with compensated cirrhosis22. A large gene-expression profiling study of cirrhotic peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) demonstrated induction of “immune paralysis” after ex vivo exposure to LPS. In comparison to healthy controls, LPS-stimulated cirrhotic PBMCs showed higher expression of certain proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines.23 Patients with HBV-related ACLF demonstrate an increase in the regulator T cells and a functional decrease of myeloid dendritic cells, which are associated with poor outcome24, 25. ACLF patients also display increased numbers of monocytes and macrophages expressing MER receptor tyrosine kinase (MERTK), which displays a potent suppressive effect on the innate immune response 26. Recent studies on the beneficial use of granulocyte-colony stimulation factor (G-CSF) for patients with ACLF, showed an increase in circulating and intrahepatic myeloid and plasmacytic dendritic and T cells. 27, 28

These findings demonstrate some similarities between the pathophysiology of ACLF and severe sepsis. Septic patients also exhibit both a proinflammatory phase, leading to multiorgan failure/dysfunction, and an antiinflammatory phase, characterized by suppression of the immune system.29, 30 Unfortunately, there are no current studies on the immune system response at the different stages of ACLF. These studies would be helpful in further understanding the sequence of events leading to organ failure and death.

In addition to bacterial translocation and infection contributed to by impaired immune response in cirrhosis, sterile mechanisms associated with hepatocellular damage may also elicit a prominent inflammatory response. Sterile inflammation, as induced by alcohol, surgery, acetaminophen or ischemic/reperfusion, is mostly driven by damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) as opposed to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS)31, 32. DAMPs derive from necrotic hepatocytes and have been demonstrated to activate host pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs)33. These in turn promote expression of adhesion proteins and release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1B, IL-18) and growth factors, which further attract and activate additional inflammatory cells34. Several DAMPs have been described in the literature, but their role in ACLF needs to be further elucidated. Recently, a small study found increased serum levels of high mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 (HMGB1), an important hepatocyte-derived DAMP, in patients with ACLF35 (Figure 2).

EXTRAHEPATIC ORGAN FAILURE

The presence of multi-system organ failure is a requirement for the diagnosis of ACLF and critical in differentiating this condition from decompensated cirrhosis. Also, the number of systems affected has important prognostic value6.

Renal System

Kidney dysfunction is common and associated with high mortality in cirrhotic patients. Overall, isolated renal failure carries a 28-day mortality rate up to 18.6% in patients with ACLF6. The diagnosis of renal failure has been defined as serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL or need for renal replacement therapy in patients with cirrhosis36, 37. A newer definition of acute renal failure has been proposed by the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) which considers the absolute change in serum creatinine or change in urine output over a 48 hour period38. The AKIN criteria have been recently validated as a prognostic tool in hospitalized cirrhotic patients on a stage dependent fashion39–42. The AKIN criteria have yet to be incorporated, however, into a prognostic score for ACLF.

The most common causes of acute kidney injury in cirrhosis include: volume-responsive prerenal azotemia, acute tubular necrosis, and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) 43. Hepatorenal syndrome is a unique form of pre-renal azotemia that is not responsive to volume expansion alone but is usually reversible with liver transplantation. HRS results from a hyperdynamic circulatory state, leading to significant renal vasoconstriction44. Management of HRS includes the use of splanchnic vasoconstrictors which promote an increase in the effective renal arterial blood volume. Vasoconstrictor drugs such as terlipressin significantly improve renal function and overall short-term survival.45 Patients with severe ACLF and sepsis-associated HRS are less likely to respond to terlipressin, suggesting alternative mechanisms of renal impairment in this population.46 In addition, response to terlipressin in ACLF may not simply be related to degree of renal impairment and other factors may play a role.47

In addition to circulatory changes, AKI in ACLF is also likely modulated by systemic inflammation. This is supported by the beneficial role of pentoxifylline in decreasing the risk of renal failure in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis 48 and the renal protective effect of intravenous albumin in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis36. Bacterial infection is the precipitating event of AKI in about 30–40% of patients with cirrhosis 49 and is an important driver of inflammation in this group. Renal failure associated with infections carries a poor prognosis, with a 3-month survival rate of 31% in one study49. Intestinal decontamination with daily oral norfloxacin in prevention of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis leads to a significant decrease in the incidence of AKI and improves survival50.

In addition to renal failure, hyponatremia is known to have an important prognostic value in cirrhosis 51. Indeed, the presence of hyponatremia in patients with ACLF was associated with lower 3-month survival compared to patients with ACLF and without hyponatremia (35.8% vs. 58.7%, respectively) 52.

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is a common complication of cirrhosis and is associated with higher in-hospital mortality53–55. Hepatic encephalopathy can present in three different settings: acute liver failure, decompensated cirrhosis, and ACLF. Isolated hepatic encephalopathy seems to occur in older cirrhotics, without evidence of extrahepatic organ dysfunction. The prognosis is typically good in this older group of patients with HE, even in those requiring ICU admission and mechanical ventilation56. HE associated with ACLF, on the other hand, occurs in the setting of extrahepatic organ failure(s) and carries a poor prognosis57. This prognostic gap is likely related to superimposed systemic inflammation, characteristic of ACLF, in addition to circulating neurotoxins such as hyperammonemia which is observed in both groups58.

Another important difference between isolated HE and HE associated with ACLF is that the latter may lead to cerebral edema and elevated intracranial pressure, whereas the former will typically not 11, 59–61. Animal studies suggest the development of acute brain edema to be a result of hyperammonemia plus systemic/neuroinflammation62. Hyponatremia has also been identified as an important risk factor for cerebral edema, likely due to differences in osmolality between the intra and extracellular spaces63, 64.

Cardiovascular system

Similar to decompensated cirrhosis, ACLF patients also demonstrate important hemodynamic changes, including a decrease in mean arterial pressure, systemic vascular resistance and cardiac index and a significant increase in hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG). These portal and systemic circulatory changes improve significantly after resolution of the acute episode and correlate well with clinical recovery65.

Systemic inflammation likely accounts for the acute vascular changes observed in ACLF, similar to septic shock. Increase in circulating proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor, promotes peripheral vasodilation 66, 67 and aggravates intrahepatic resistance 68. Also, patients with ACLF may demonstrate relative adrenal insufficiency and, consequently, low serum cortisol levels69. This in turn, results in decreased peripheral response to vasoconstrictors69, 70.

Respiratory System

Respiratory failure in patients with ACLF is usually related to pulmonary infections, although patients may require mechanical ventilation for other indications, including airway protection during variceal bleeding and/or advanced grades of hepatic encephalopathy. Pulmonary infections account for 14% to 48% of all infections in cirrhotic patients 71. Both acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) occur. The need for mechanical ventilation is a poor prognostic indicator in ACLF, with 1-year mortality at 89%. Ventilation longer than 9 days, and elevated total bilirubin at ICU discharge were identified as independent risk factors associated with high mortality72.

Coagulation System

Prolonged prothrombin time and low platelet count are common features of cirrhosis and are used as surrogate markers of coagulation dysfunction in this population. Unfortunately, the abnormalities in the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems are extensive and not recognized by routine testing73. In stable cirrhosis, both the pro- and anti-coagulant factors are equally decreased, resulting in either normal thrombin generation, or a tendency to hypercoagulability74. Bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients are thought to impair coagulation by increasing endogenous heparinoids. This seems to be a temporary effect which resolves after the infection has cleared75. Platelet dysfunction has also been observed in infected patients, especially those with renal failure, and likely contributes to the hemostatic impairment76. These detrimental vascular effects are further countered by the protective role of antibiotics in reducing early variceal rebleeding rates77.

POTENTIAL BIOMARKERS

As our understanding and recognition of ACLF increases, so does our need to accurately diagnose and risk stratify patients for better outcome prediction and therapy guidance. Currently, only a few studies have investigated potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of ACLF. A recent study evaluating the metabolomic profile of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis admitted to the hospital with ACLF identified signals related to ACLF, compared to compensated or decompensated cirrhosis, including lactate, pyruvate, ketone bodies, glutamine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and creatinine 78. Metabolic profiling has been applied in patients with HBV-related ACLF and 38 characteristic serum metabolites were identified, 17 of which also demonstrated a potential prognostic role79. Systemic inflammatory response is an important pathophysiologic feature of ACLF, and therefore, inflammatory or immune markers have also been investigated in this condition. A significant up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon gamma was observed in HBV-related ACLF, compared to chronic hepatitis and normal controls80.

However, more data are required before these biomarkers can be widely applied as diagnostic or prognostic tools.

PREDICTIVE MODELS

Multiple scoring systems have been employed or developed to help predict outcomes in patients with ACLF. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score (MELD score), the Maddrey discriminant function and the Lille model have been shown to predict early mortality in acute alcoholic hepatitis81–84. A recent study in patients with alcoholic hepatitis has shown that the combination of MELD score at admission and Lille score after one week of steroids has the best discriminant as well as calibration value of all models or combination of models.85 This combined model may help in making treatment decisions including selecting patients for specific treatments as well as determining futility of care.86 A combination of the MELD score, age and American Society of Anesthesiologists classification has been validated for predicting survival in cirrhotic patients undergoing surgery, another common precipitant of ACLF87.

The commonly used scoring systems in cirrhosis, i.e. Child-Turcotte-Pugh score and MELD score, only assess, in addition to the liver, the kidney, brain and coagulation systems 88. Therefore, an improved scoring system for ACLF is required which takes into consideration inflammation and other organ dysfunction. Recently, the EASL-CLIF Consortium proposed a modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (SOFA) to include factors associated with chronic liver disease (CLIF-SOFA scale)6.

The CLIF-SOFA scale assessed the function of 6 organ systems (liver, kidneys, brain, coagulation, circulation and lungs) (Table 2). A recent retrospective study, including 971 patients, validated the use of CLIF-SOFA score in cirrhosis. The SOFA and CLIF-SOFA had similar abilities to predict patient survival, with greater area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) values than those obtained from MELD and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores.89

Table 2.

CLIF SOFA score system

| Organ | Measurement | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | ||

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | <1.2 | 0 |

| ≥1.2 to <2.0 | 1 | |

| ≥2.0 to <6.0 | 2 | |

| ≥6.0 to <12.0 | 3 | |

| ≥12.0 | 4 | |

|

| ||

| Kidney | ||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | <1.2 | 0 |

| ≥1.2 to <2.0 | 1 | |

| ≥2.0 to <3.5 | 2 | |

| ≥3.5 to <5.0 | 3 | |

| ≥5.0 or RRT | 4 | |

|

| ||

| Coagulation | ||

| INR | <1.1 | 0 |

| ≥1.1 to <1.25 | 1 | |

| ≥1.25 to <1.5 | 2 | |

| ≥1.5 to <2.5 | 3 | |

| ≥2.5 or platelet count ≤20,000 | 4 | |

|

| ||

| Circulation | ||

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | ≥70 | 0 |

| <70 | 1 | |

| Dopamine ≤5 or dobutamine or terlipressin | 2 | |

| Dopamine >5 or E ≤ 0.1 or NE ≤ 0.1 | 3 | |

| Dopamine >15 or E >0.1 or NE >0.1 | 4 | |

|

| ||

| Respiratory | ||

| PaO2/FiO2 | >400 | 0 |

| >300 to ≤ 400 | 1 | |

| <200 to ≤ 300 | 2 | |

| >100 to ≤ 200 | 3 | |

| ≤ 100 | 4 | |

| SpO2/FiO2 | >512 | 0 |

| >357 to ≤ 512 | 1 | |

| >214 to ≤357 | 2 | |

| >89 to ≤ 214 | 3 | |

| ≤ 89 | 4 | |

|

| ||

| Cerebral | ||

| No HE | 0 | |

| I | 1 | |

| II | 2 | |

| III | 3 | |

| IV | 4 | |

A simplification of the CLIF-SOFA score has been proposed. Two new cut-points for each organ system have been added to distinguish three severity categories that were correlated with 28-day mortality (CLIF-C OFs). The “CLIF-C OFs” had a similar performance to the original CLIF-SOFA score in predicting 28-day mortality. The authors then developed a mathematical model, including age and white blood cell count, to improve the CLIF-C OFs performance. This new score, CLIF-C ACLFs, was proven to be superior to MELD and MELD-Na in predicting mortality in ACLF in the study population and in an externally validated cohort.90

In contrast to these elaborate models, Bajaj et al. using data from the NASCELD group proposed the mere presence of increasing number of organ failures may be sufficient to accurately predict short term mortality at least among persons with ACLF that develop an infection. Hence, the overarching theme is that regardless of the underlying liver disease, it is the presence of multiorgan failure that predominantly drives the outcomes.

Gustot and colleagues assessed ACLF grades at different time points to evaluate the clinical course in this group of patients. Interestingly, they found that ACLF grade at 3–7 days was a better predictor of severity independent of initial assessment. Patients with non-severe early course had a 28-day transplant-free mortality of 6–18%, compared to 42–92% mortality in patients with severe early course.91 It is yet unclear whether these organ failure scores are truly prognostic (that is, allow early recognition and can improve the outcome) or are only reflective (that is, they are describing the dying process).

THERAPIES

There is no ACLF specific treatment; rather treatment follows the paradigm of addressing the predisposing event, preventing injury, attenuating the inflammatory response and providing supporting care for ensuing organ failures (Table 3). Appropriate intensive care management of subjects with ACLF is the mainstay of treatment.10 Early recognition of subjects at highest propensity to either present with or develop ACLF is important so that urgent evaluation for liver transplantation can take place. The role of alcohol as a common precipitant is a confounding factor given the variability of center specific criteria for abstinence.

Table 3.

Management of ACLF based on the PIRO model for assessment and intervention in ACLF (adapted from Jalan et al. Gastroenterology 2014)

| Assessment | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposition | Severity, Etiology | MELD score, CTP score | |

| Injury | Precipitating Event | Viral Hepatitis | Early antivirals for hepatitis B Prednisone? |

| Alcohol | |||

| Drugs | |||

| Infection | Early Antibiotics | ||

| Nosocomial Infection coverage | |||

| Response | Inflammation | GCSF? | |

| Immune Failure | Role of albumin? | ||

| Organ failure | Number of organs | Renal Failure | Early RRT |

| Cardiopulmonary | Intensive Care | ?goal Directed Therapy | |

| Prognostic Score | SOFA, APACHE, CLIF | Artificial/Bio- artificial liver in selected patients? Liver transplantation |

Management of any decompensation is contingent on first addressing the precipitating event. For example, in the setting of acute alcoholic hepatitis, administration of prednisolone early in the course may play a role if warranted by the severity of disease. However, the interplay between the high prevalence of infection amongst persons with ACLF and administration of prednisolone is unknown. Further, the absolute reduction in mortality with steroid based therapy is apparent only at 28 days; long-term reduction in mortality is related to abstaining from alcohol. Reduction of risk of infection with early use of antibiotics in persons with gastrointestinal bleeding may improve outcomes. Administration of antiviral therapy for ACLF due to reactivation of hepatitis B may lead to improved survival.92 In a single center study from India, subjects with spontaneous reactivation of chronic hepatitis B with ACLF and no access to LT were randomized to receive of either tenofovir or placebo. Three-month survival was higher amongst persons receiving tenofovir as compared to the placebo group (57% vs. 15%). In a recent meta-analysis, subjects with ACLF who received nucleos(t)ide analogues had significantly lower 3-month mortality (45% vs. 73%, p < 0.01) as well as incidence of reactivation (1.8% vs. 18%, p< 0.01) compared to those who did not.93

The role of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as a promoter of hepatic regeneration has been reported in small group of patients with ACLF and a larger group of subjects with decompensated cirrhosis.28 In this latter single center placebo controlled randomized trial, receipt of a combination of G-CSF and darbopoietin α was associated with improved survival at 1 year (68.6% vs 26.9%; p<0.01) with a lower rate of septic shock in follow up (6.9% vs. 38.5%, p<0.01).27

The role of liver assist devices remain unclear.94 MARS (Gambro), a non-biologic molecular adsorbent recirculating system was examined among persons with ACLF. In the RELIEF multicenter study which included 180 patients with ACLF, there was no survival difference between patients randomized to MARS or standard therapy (28-day mortality was 41% vs. 40% and subjects with MARS vs. standard of care alone).95 In a study of another nonbiological device, Prometheus ®, using fractional plasma separation absorption and dialysis, survival benefit was not observed in persons with ACLF (mortality was 34% vs. 37% in subjects assigned to the device vs. standard of care). There was survival benefit seen only amongst persons with type I hepatorenal syndrome and MELD scores greater than 30.94 Bio-artificial liver assist devices are also being studied. (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01471028)

LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Currently, there is no urgent status assigned to persons with ACLF and it is unclear whether ALF criteria should be applied to subjects with ACLF. Given that timing of LT is important, it is also unclear whether King’s college hospital ALF criteria should also be applied for ACLF or whether MELD based organ allocation is appropriately applicable. Driven by the presence of multi-organ failure, subjects with ACLF often have high MELD scores. Candidates with MELD scores above 35 have higher wait list mortality than status 1 patients and receive priority for liver transplantation second only to patients with ALF.96 However, the presence of severe cerebral edema, intracranial bleeding, active infection in a majority, need for ventilator support and hemodynamic instability that may be present in persons with ACLF are obvious contraindications to transplantation.7 Further, recent data suggests that certain diagnoses previously not considered for LT globally such as acute alcoholic hepatitis may have acceptable outcomes after liver transplantation. In a single center European cohort inclusive of ACLF with acute alcoholic hepatitis (2002–2010, mean MELD 28, 144 subjects) 97, only 10 persons survived without LT over a median follow up of 1.5 years. Among the highly selected 33 patients who underwent liver transplantation, the 1- and 5-year survival rates of 87% and 82% were comparable to the rates for non-ACLF patients. Subjects with better renal function and lower CRP were more likely to receive a LT as compared to those patients with sepsis or needing mechanical ventilation. Bahirwani et al. examined subjects with ACLF between 2002 and 2006 (50% hepatitis C) at a large American transplant center. ACLF was defined as a rise in MELD score of 5 points within 4 weeks before LT. There was no significant difference in deaths post-transplant or renal failure after LT. ACLF was not a predictor of death after LT but was a significant predictor when simultaneous liver-kidney transplant (SLKT) was included. In another recent single center study from China (100 patients, 2004–2012, mean MELD 32), the 1 and 5-year cumulative survival rates were 76.8% and 74.1%, respectively post-transplant. In all studies, no comparison was performed between patients with ACLF and those with chronic decompensation matched for disease severity by the MELD score.

The role of living donor LT has also been evaluated for subjects with ACLF due to reactivation of hepatitis B virus infection98–100 In a single center study the 5 year survival rate was 93% for persons with ACLF due to chronic hepatitis B, 90% for other causes of ACLF, 79% for persons with other causes of cirrhosis, and 91% for persons with acute liver failure. Overall hepatitis B was disproportionately represented across all the etiologies..99

The role of SLKT for ACLF patients with renal dysfunction was recently examined among persons undergoing deceased donor transplantation (China, 133 subjects, 2001–2009).101 The survival rate for those without renal dysfunction was 72% at 5 years which was comparable to 82% for those that underwent simultaneous liver and kidney transplantation. Subjects with ACLF due to hepatitis B and hepatorenal syndrome that only underwent LT alone had a 5 year survival rate of 56%.

Conclusion

ACLF is an increasingly recognized entity associated with high mortality. The pathogenesis of inflammation and organ failure, and optimal management are the subject of intensive investigation across continents. More data are required before ACLF can be accurately defined and treated. Future strategies include defining the group of patients who need urgent liver transplantation; those who would benefit from intensive care alone; those who will benefit from liver supportive devices or hepatic regenerative therapies; and those patients in whom all intervention is futile.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: none

List of Abbreviations

- LT

liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for end stage liver disease

- INR

international normalized ratio

- SLK

simultaneous liver–kidney transplantation

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ALF

acute liver failure

- ACLF

acute-on-chronic liver failure

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None of the authors have conflicts of interest or any specific financial interests relevant to the subject of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fleming KM, Aithal GP, Card TR, et al. All-cause mortality in people with cirrhosis compared with the general population: A population-based cohort study. Liver International. 2012;32:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jepsen P, Ott P, Andersen PK, et al. Clinical course of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a Danish population-based cohort study. Hepatology. 2010;51:1675–82. doi: 10.1002/hep.23500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jalan R, Yurdaydin C, Bajaj JS, et al. Toward an improved definition of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:4–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasmuth HE, Kunz D, Yagmur E, et al. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display ‘sepsis-like’ immune paralysis. Journal of Hepatology. 2005;42:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1170–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1400974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–37. 1437 e1–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL) Hepatol Int. 2009;3:269–82. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, Yang Y, Hu Y, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure precipitated by hepatic injury is distinct from that precipitated by extrahepatic insults. Hepatology. 2015;62:232–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.27795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Reddy KR, et al. Survival in infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure is defined by extrahepatic organ failures. Hepatology. 2014;60:250–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.27077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olson JC, Wendon JA, Kramer DJ, et al. Intensive care of the patient with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1864–1872. doi: 10.1002/hep.24622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jalan R, Gines P, Olson JC, et al. Acute-on Chronic Liver Failure. J Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosselli M, MacNaughtan J, Jalan R, et al. Beyond scoring: A modern interpretation of disease progression in chronic liver disease. Gut. 2013;62:1234–1241. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargenti K, Prytz H, Nilsson E, et al. Predictors of mortality among patients with compensated and decompensated liver cirrhosis: the role of bacterial infections and infection-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1017834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruno S, Saibeni S, Bagnardi V, et al. Mortality risk according to different clinical characteristics of first episode of liver decompensation in cirrhotic patients: a nationwide, prospective, 3-year follow-up study in Italy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1112–22. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escorsell Manosa A, Mas Ordeig A. Acute on chronic liver failure. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;33:126–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen AM. The Economic Burden and Mortality of Patients with Acute on Chronic Liver Failure (ACLF) in the United States. Hepatology. 2014;60:485a. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson JC, Kamath PS. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: what are the implications? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:63–6. doi: 10.1007/s11894-011-0228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olson JC, Kamath PS. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: concept, natural history, and prognosis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:165–9. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328344b42d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:840–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilzer M, Roggel F, Gerbes AL. Role of Kupffer cells in host defense and liver disease. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2006;26:1175–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albillos A, Lario M, Alvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. Journal of hepatology. 2014;61:1385–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wasmuth HE, Kunz D, Yagmur E, et al. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display “sepsis-like” immune paralysis. Journal of hepatology. 2005;42:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gandoura S, Weiss E, Rautou PE, et al. Gene- and exon-expression profiling reveals an extensive LPS-induced response in immune cells in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;58:936–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong X, Gong Y, Zeng H, et al. Imbalance between circulating CD4+ regulatory T and conventional T lymphocytes in patients with HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2013;33:1517–26. doi: 10.1111/liv.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J, Zhang JY, Yu HW, et al. Improved survival ratios correlate with myeloid dendritic cell restoration in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients receiving methylprednisolone therapy. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2012;9:417–22. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernsmeier C, Pop OT, Singanayagam A, et al. Patients With Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Have Increased Numbers of Regulatory Immune Cells Expressing the Receptor Tyrosine Kinase MERTK. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:603–615. e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kedarisetty CK, Anand L, Bhardwaj A, et al. Combination of Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor and Erythropoietin Improves Outcomes of Patients with Decompensated Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg V, Garg H, Khan A, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilizes CD34(+) cells and improves survival of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:505–512. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: from cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:862–74. doi: 10.1038/nri3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaeschke H. Reactive oxygen and mechanisms of inflammatory liver injury: Present concepts. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2011;26 (Suppl 1):173–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kubes P, Mehal WZ. Sterile inflammation in the liver. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1158–72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu P, Duan L, Chen J, et al. Gene silencing of NALP3 protects against liver ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Human gene therapy. 2011;22:853–64. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrasek J, Bala S, Csak T, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammasome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:3476–89. doi: 10.1172/JCI60777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou RR, Liu HB, Peng JP, et al. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients and mice with ConA-induced acute liver injury. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2012;93:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:403–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Angeli P, Fasolato S, Mazza E, et al. Combined versus sequential diuretic treatment of ascites in non-azotaemic patients with cirrhosis: results of an open randomised clinical trial. Gut. 2010;59:98–104. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.176495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Critical care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Piano S, Rosi S, Maresio G, et al. Evaluation of the Acute Kidney Injury Network criteria in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites. J Hepatol. 2013;59:482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fagundes C, Barreto R, Guevara M, et al. A modified acute kidney injury classification for diagnosis and risk stratification of impairment of kidney function in cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2013;59:474–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belcher JM, Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, et al. Association of AKI with mortality and complications in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;57:753–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Carvalho JR, Villela-Nogueira CA, Luiz RR, et al. Acute kidney injury network criteria as a predictor of hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2012;46:e21–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31822e8e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Tsao G, Parikh CR, Viola A. Acute kidney injury in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;48:2064–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.22605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gines P, Schrier RW. Renal failure in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1279–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0809139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gluud LL, Christensen K, Christensen E, et al. Systematic review of randomized trials on vasoconstrictor drugs for hepatorenal syndrome. Hepatology. 2010;51:576–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.23286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez E, Elia C, Sola E, et al. Terlipressin and albumin for type-1 hepatorenal syndrome associated with sepsis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:955–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jindal A, Bhadoria AS, Maiwall R, et al. Evaluation of acute kidney injury and its response to terlipressin in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Liver Int. 2015 doi: 10.1111/liv.12895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, et al. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1637–48. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin-Llahi M, Guevara M, Torre A, et al. Prognostic importance of the cause of renal failure in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:488–496. e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandez J, Navasa M, Planas R, et al. Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis delays hepatorenal syndrome and improves survival in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:818–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1018–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cardenas A, Sola E, Rodriguez E, et al. Hyponatremia influences the outcome of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure: an analysis of the CANONIC study. Critical care. 2014;18:700. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0700-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahimi RS, Rockey DC. Complications of cirrhosis. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2012;28:223–9. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328351d003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716–21. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stepanova M, Mishra A, Venkatesan C, et al. In-hospital mortality and economic burden associated with hepatic encephalopathy in the United States from 2005 to 2009. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2012;10:1034–41. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fichet J, Mercier E, Genee O, et al. Prognosis and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit patients with severe hepatic encephalopathy. Journal of critical care. 2009;24:364–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cordoba J, Ventura-Cots M, Simon-Talero M, et al. Characteristics, risk factors, and mortality of cirrhotic patients hospitalized for hepatic encephalopathy with and without acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) Journal of hepatology. 2014;60:275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shawcross DL, Davies NA, Williams R, et al. Systemic inflammatory response exacerbates the neuropsychological effects of induced hyperammonemia in cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology. 2004;40:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donovan JP, Schafer DF, Shaw BW, Jr, et al. Cerebral oedema and increased intracranial pressure in chronic liver disease. Lancet. 1998;351:719–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07373-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joshi D, O’Grady J, Patel A, et al. Cerebral oedema is rare in acute-on-chronic liver failure patients presenting with high-grade hepatic encephalopathy. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2013 doi: 10.1111/liv.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nath K, Saraswat VA, Krishna YR, et al. Quantification of cerebral edema on diffusion tensor imaging in acute-on-chronic liver failure. NMR in biomedicine. 2008;21:713–22. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wright G, Davies NA, Shawcross DL, et al. Endotoxemia produces coma and brain swelling in bile duct ligated rats. Hepatology. 2007;45:1517–26. doi: 10.1002/hep.21599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cordoba J, Garcia-Martinez R, Simon-Talero M. Hyponatremic and hepatic encephalopathies: similarities, differences and coexistence. Metabolic brain disease. 2010;25:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11011-010-9172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cordoba J, Gottstein J, Blei AT. Chronic hyponatremia exacerbates ammonia-induced brain edema in rats after portacaval anastomosis. Journal of hepatology. 1998;29:589–94. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garg H, Kumar A, Garg V, et al. Hepatic and systemic hemodynamic derangements predict early mortality and recovery in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2013;28:1361–7. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stadlbauer V, Krisper P, Aigner R, et al. Effect of extracorporeal liver support by MARS and Prometheus on serum cytokines in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Critical care. 2006;10:R169. doi: 10.1186/cc5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lopez-Talavera JC, Merrill WW, Groszmann RJ. Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a major contributor to the hyperdynamic circulation in prehepatic portal-hypertensive rats. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:761–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mehta G, Mookerjee RP, Sharma V, et al. Systemic inflammation is associated with increased intrahepatic resistance and mortality in alcohol-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Liver international : official journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. 2015;35:724–34. doi: 10.1111/liv.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fernandez J, Escorsell A, Zabalza M, et al. Adrenal insufficiency in patients with cirrhosis and septic shock: Effect of treatment with hydrocortisone on survival. Hepatology. 2006;44:1288–95. doi: 10.1002/hep.21352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aravinthan A, Al-Naeeb Y, Richardson P. Relative adrenal insufficiency in a patient with liver disease. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2009;21:381–3. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328309c77e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Christou L, Pappas G, Falagas ME. Bacterial infection-related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007;102:1510–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levesque E, Saliba F, Ichai P, et al. Outcome of patients with cirrhosis requiring mechanical ventilation in ICU. Journal of hepatology. 2014;60:570–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kar R, Kar SS, Sarin SK. Hepatic coagulopathy-intricacies and challenges; a cross-sectional descriptive study of 110 patients from a superspecialty institute in North India with review of literature. Blood coagulation & fibrinolysis : an international journal in haemostasis and thrombosis. 2013;24:175–80. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835b2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lisman T, Bakhtiari K, Pereboom IT, et al. Normal to increased thrombin generation in patients undergoing liver transplantation despite prolonged conventional coagulation tests. Journal of hepatology. 2010;52:355–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Montalto P, Vlachogiannakos J, Cox DJ, et al. Bacterial infection in cirrhosis impairs coagulation by a heparin effect: a prospective study. Journal of hepatology. 2002;37:463–70. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vincent JL, Yagushi A, Pradier O. Platelet function in sepsis. Critical care medicine. 2002;30:S313–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jun CH, Park CH, Lee WS, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis using third generation cephalosporins can reduce the risk of early rebleeding in the first acute gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage: a prospective randomized study. Journal of Korean medical science. 2006;21:883–90. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.5.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amathieu R, Triba MN, Nahon P, et al. Serum 1H-NMR metabolomic fingerprints of acute-on-chronic liver failure in intensive care unit patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. PloS one. 2014;9:e89230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nie CY, Han T, Zhang L, et al. Cross-sectional and dynamic change of serum metabolite profiling for Hepatitis B-related acute-on-chronic liver failure by UPLC/MS. Journal of viral hepatitis. 2014;21:53–63. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zou Z, Li B, Xu D, et al. Imbalanced intrahepatic cytokine expression of interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-10 in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2009;43:182–90. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181624464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dunn W, Angulo P, Sanderson S, et al. Utility of a new model to diagnose an alcohol basis for steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1057–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dunn W, Jamil LH, Brown LS, et al. MELD accurately predicts mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005;41:353–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Monsanto P, Almeida N, Lrias C, et al. Evaluation of MELD score and Maddrey discriminant function for mortality prediction in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2013;60:1089–94. doi: 10.5754/hge11969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.21607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Louvet A, Labreuche J, Artru F, et al. Combining Data from Liver Disease Scoring Systems Better Predicts Outcomes of Patients with Alcoholic Hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kamath PS, Therneau T, Shah VH. MELDing the Lille Score to More Accurately Predict Mortality in Alcoholic Hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Teh SH, Nagorney DM, Stevens SR, et al. Risk Factors for Mortality after Surgery in Patients with Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.040. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–70. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McPhail MJ, Shawcross DL, Abeles RD, et al. Increased Survival for Patients With Cirrhosis and Organ Failure in Liver Intensive Care and Validation of the Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Scoring System. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Journal of hepatology. 2014;61:1038–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gustot T, Fernandez J, Garcia E, et al. Clinical Course of acute-on-chronic liver failure syndrome and effects on prognosis. Hepatology. 2015;62:243–52. doi: 10.1002/hep.27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garg H, Sarin SK, Kumar M, et al. Tenofovir improves the outcome in patients with spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B presenting as acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology. 2011;53:774–780. doi: 10.1002/hep.24109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yu S, Jianqin H, Wei W, et al. The efficacy and safety of nucleos(t)ide analogues in the treatment of HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: a meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:364–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hassanein TI, Schade RR, Hepburn IS. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: extracorporeal liver assist devices. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:195–203. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328344b3aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Banares R, Nevens F, Larsen FS, et al. Extracorporeal albumin dialysis with the molecular adsorbent recirculating system in acute-on-chronic liver failure: the RELIEF trial. Hepatology. 2013;57:1153–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.26185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sharma P, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, et al. End-stage liver disease candidates at the highest model for end-stage liver disease scores have higher wait-list mortality than status-1A candidates. Hepatology. 2012;55:192–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.24632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Finkenstedt A, Nachbaur K, Zoller H, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: excellent outcomes after liver transplantation but high mortality on the wait list. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:879–86. doi: 10.1002/lt.23678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chok KS, Fung JY, Chan SC, et al. Outcomes of living donor liver transplantation for patients with preoperative type 1 hepatorenal syndrome and acute hepatic decompensation. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:779–85. doi: 10.1002/lt.23401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chan AC, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:571–81. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9148-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. Live-donor liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. Transplantation. 2003;76:1174–1179. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000087341.88471.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xing T, Zhong L, Chen D, et al. Experience of combined liver-kidney transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure patients with renal dysfunction. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]