Abstract

Proliferative GN is classified as immune complex-mediated or complement-mediated (C3 glomerulopathy). Immune complex-mediated GN results from glomerular deposition of immune-complexes/Ig and C3; the C3 is derived from activation of the classical and/or lectin pathways of complement. C3 glomerulopathy results from deposition of C3 and other complement fragments with minimal or no deposition of immune complexes/Ig; the C3 is derived from activation of the alternative pathway of complement. C4d is a byproduct of activation of the classic and lectin pathways. Although widely used as a marker for antibody-mediated rejection, the significance of C4d in C3 glomerulopathy is undetermined. We studied glomerular C4d staining in 18 biopsy specimens of immune-complex GN, 30 biopsy specimens of C3 GN, and 13 biopsy specimens of postinfectious GN. All specimens of immune complex-mediated GN, except two specimens of IgA nephropathy and one specimen of sclerosing membranoproliferative GN, showed bright (2–3+) C4d staining. The staining pattern of C4d mirrored the staining patterns of Ig and C3. Conversely, C4d staining was completely negative in 24 (80%) of 30 specimens of C3 glomerulopathy, and only trace/1+ C4d staining was detected in six (20%) specimens. With regard to postinfectious GN, C4d staining was negative in six (46%) of 13 specimens, suggesting an abnormality in the alternative pathway, and it was positive in seven (54%) specimens. To summarize, C4d serves as a positive marker for immune complex-mediated GN but is absent or minimally detected in C3 glomerulopathy.

Keywords: glomerulonephritis, immunology and pathology, kidney biopsy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), renal pathology

Proliferative GN has recently been classified into immune complex-mediated GN and complement-mediated GN (Mayo classification of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis [MPGN]).1–3 The classification is on the basis of pathophysiology and is guided by immunofluorescence findings. Immune complex-mediated GN is caused by glomerular deposition of immune complexes or Igs as a result of infections, autoimmune diseases, or monoclonal gammopathy, pathologies characterized by activation of the classical pathway (CP) or lectin pathway (LP) of complement. On the other hand, complement-mediated GN, also termed C3 glomerulopathy, is caused by glomerular deposition of complement factors resulting from dysregulation of the alternative pathway (AP) of complement.4–7 C3 glomerulopathy includes C3 GN and dense deposit disease (DDD).8

Immunofluorescence is the key to the Mayo classification. Immune complex-mediated GN shows Ig on immunofluorescence, often along with C3, the latter because of activation of the CP by the immune complexes or LP by microbial surfaces. On the other hand, there is bright staining for C3, and Igs are typically negative in complement-mediated GN/C3 glomerulopathy. However, a proportion of C3 glomerulopathy biopsies may show small amounts of Igs on immunofluorescence.9,10 As a result, the definition of C3 glomerulopathy now states that C3 staining should be dominant and at least 2 orders of magnitude more intense than any other immune reactants.8 This can lead to interobserver variability. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the Igs are entrapped plasma proteins in areas of scarring or represent true immune-complex deposition.

Immune complexes activate the CP of complement via binding of C1q to the immune complexes, resulting in activation of C4 and generation of CP C4 convertase. Therefore, C1q binding to IgG/IgM represents an early step in the activation of the CP. C4d is a split product of C4 activation and serves as a downstream marker of CP activation. Activation of C4 can also occur via activation of the LP, in which mannose binding lectins bind to bacterial carbohydrate moieties and activate C4, resulting in generation of the C4 convertase.11–13 Therefore, C4d can also be a product of LP activation. C4d is widely used as marker of antibody-mediated rejection,14,15 and studies have also shown that it is positive in immune complex- or Ig-mediated GN, such as lupus nephritis, membranous nephropathy, antiglomerular basement membrane GN, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody crescentic GN.16–22 Recently, it was shown that C4d staining in IgA nephropathy might serve as a poor prognostic factor.11 However, studies have not been done regarding its potential role in the diagnosis of C3 glomerulopathy.

We hypothesized that positive glomerular staining for C4d can serve as a marker for immune complex-mediated GN because the CP is activated by the immune complexes. Positive C4d can also serve as a marker for GN resulting from activation of the LP.12,13,19 On the other hand, negative glomerular staining for C4d can serve as a marker for C3 glomerulopathy because the CP and LP are not activated in C3 glomerulopathy. In addition, we hypothesized that the trace/scant Ig staining seen in some patients with C3 glomerulopathy—if indeed nonspecific because of entrapment—should have no effect on C4d presence in C3 glomerulopathy, or may indicate a subset of patients that also have CP/LP activation. We also compared the presence of C1q and C4d in immune complex- and complement-mediated GN.

Results

Glomerular C4d Staining in Immune Complex-Mediated GN

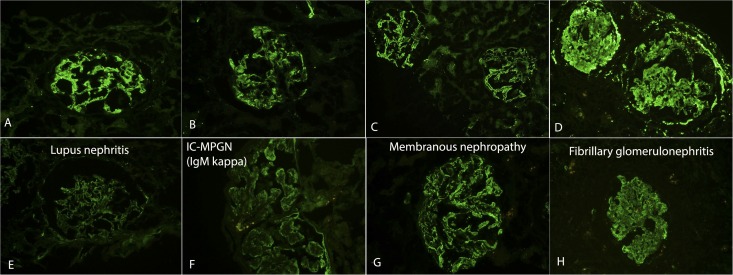

We selected 18 recent biopsies of immune complex-mediated GN. These included two patients with IgA nephropathy, five patients with membranoproliferative GN (one because of hepatitis C, two because of monoclonal Ig, one because of autoimmune disease, and one who was undefined [patient 13], which will be subsequently discussed), four patients with membranous nephropathy, five patients with lupus nephritis, and two patients with fibrillary GN. The immunofluorescence findings are shown in Table 1. All biopsies showed 2–3+ Ig staining on immunofluorescence. Except for one biopsy of IgA nephropathy that showed only 1+ C3 staining, all biopsies also showed bright 2–3+ staining for C3. In addition, C1q was noted in five biopsies, four of which were patients with lupus nephritis, and one was a patient with MPGN caused by autoimmune disease.

Table 1.

C4d staining in immune complex-mediated GN

| Patient | Pathology Diagnosis | C4d | C3 | C1q | Ig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chronic MPGN, monoclonal gammopathy associated (κ light chains) | 1–2 | 3 | 0 | κ 3+negative IgG, IgM, IgA, λ |

| 2 | MPGN, hepatitis C associated | 2 | 3 | 0 | IgM 3+, IgG 2+, κ 3+, λ 2+ |

| 3 | MPGN, monoclonal gammopathy associated (IgM κ) | 3 | 3 | 0 | IgM 3+, κ 3+negative IgA, IgG |

| 4 | IgA nephropathy | 0 | 1 | 0 | IgA 3+, IgM 1+, κ 2+, λ 2+ |

| 5 | Lupus nephritis | 3 | 3 | 1 | IgA 2+, IgG 3+, IgM 2+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 6 | Membranous nephropathy | 3 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 7 | Membranous nephropathy | 3 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, IgM 2+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 8 | IgA nephropathy | 0 | 2 | 0 | IgA 3+, κ 2+, λ 3+ |

| 9 | Lupus nephritis | 3 | 3 | 2 | IgA 3+, IgG 3+, IgM 2+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 10 | MPGN, autoimmune | 3 | 3 | 2 | IgG 3+, IgA 3+, IgM 3+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 11 | Fibrillary GN | 3 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, κ 2+, λ 3+ |

| 12 | Membranous nephropathy | 2 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 13 | MPGN (C3GN versus immune complex-mediated) | 3 | 3 | 0 | IgG 1+, κ 1+ |

| 14 | Lupus membranous, early | 2 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, κ 2–3+, λ 2–3+ |

| 15 | Membranous nephropathy | 2 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 16 | Lupus nephritis | 3 | 3 | 3 | IgA 3+, IgG 3+, IgM 1+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 17 | Lupus nephritis | 3 | 2 | 3 | IgA 3+, IgG 3+, IgM 2+, κ 3+, λ 3+ |

| 18 | Fibrillary GN | 3 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, κ 2+, λ 3+ |

C4d staining was negative in both instances of IgA nephropathy. The remaining biopsies of immune complex-mediated GN were positive for C4d and mirrored the distribution of Ig and C3 with respect to mesangial and capillary location. Representative immunofluorescence findings are shown in Figure 1. The intensity of C4d was 2–3+, except for one patient with MPGN (patient 1). Biopsy findings in this patient revealed a very chronic MPGN.

Figure 1.

C3 and C4d staining in immune complex (IC)-mediated GN. Top panel shows staining for C3, and bottom panel shows staining for C4d. Each vertical panel represents one patient: (A) and (E) show lupus nephritis, (B) and (F) show MPGN because of monoclonal Ig deposits, (C) and (G) show membranous nephropathy, and (D) and (H) show fibrillary GN.

In one patient (patient 13), the differential diagnosis included an MPGN because of monoclonal Ig deposits versus C3 GN because there was only weak staining for IgG κ and bright staining for C3. This biopsy showed bright C4d staining, suggesting that the MPGN was caused by monoclonal IgG κ deposition.

Glomerular C4d Staining in C3 Glomerulopathy

We selected 30 recent biopsies of C3 glomerulopathy for C4d staining. The immunofluorescence findings are shown in Table 2. Some of the patients were included in our recent series on C3 GN.6,23 Of the 30 biopsies, five showed DDD, and 25 showed C3 GN, of which three were previously diagnosed as MPGN type I and one as MPGN type III. Review of the biopsies showed that all four patients fit the criteria of C3 GN on the basis of the C3 glomerulopathy consensus report (intensity of C3 >2 orders of magnitude more than any other immune reactant on a scale of 0–3).8 The study included one patient with recurrent C3 GN and one patient with recurrent DDD in kidney transplant. Out of the 30 biopsies, 24 showed a membranoproliferative, three showed a mesangial proliferative, and three showed a diffuse proliferative pattern of injury.

Table 2.

Glomerular C4d staining in C3 glomerulopathy

| Patient | Pathology Diagnosis | C4d | C3 | C1q | Ig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | C3 GN/MPGN I | Trace–1 | 3 | 0 | IgG 1+ |

| 3 | C3 GN/MPGN I | 1 | 3 | 2 | IgG 1+ |

| 4 | DDD | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | C3 GN | 0 | 2–3 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | C3 GN/MPGN I | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | C3 GN/MPGN type III | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | C3 GN, recurrent | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | C3 GN | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | IgG 1+ |

| 17 | C3 GN | Trace | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | C3 GN | 0 | 2–3 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | C3 GN | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | C3 GN | Trace | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | C3 GN | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 24 | C3 GN | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | C3 GN | 1+ | 3 | 0 | IgG 1+ |

| 26 | DDD, recurrent | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 | DDD | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | DDD | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | DDD | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | DDD | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

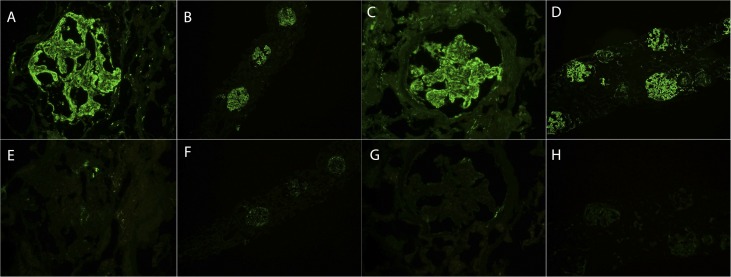

All 30 biopsies showed bright staining for C3, 28 biopsies showed 3+ staining for C3, and two biopsies showed 2–3+ staining for C3. Interestingly, four biopsies showed trace to 1+ staining for IgG. C1q was negative in all patients except for one (patient 3).

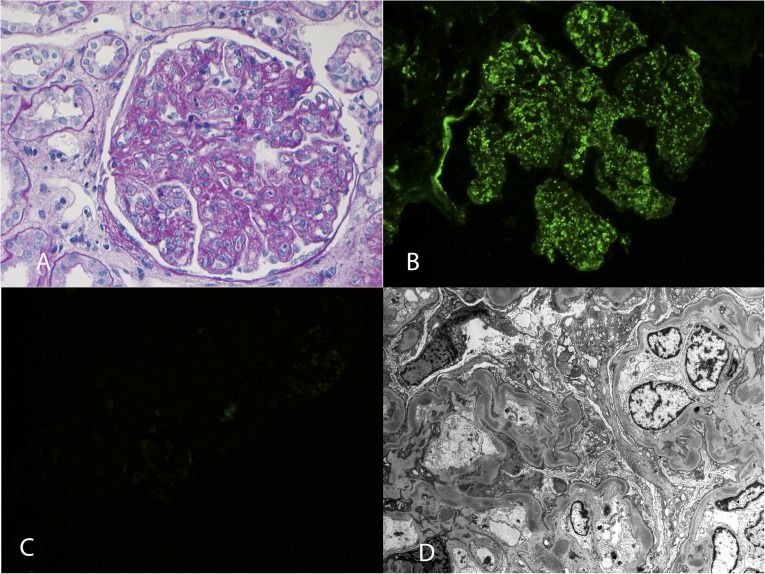

C4d staining was negative in 24 (80%) of 30 biopsies of C3 glomerulopathy, whereas there was only trace to 1+ C4d staining in the remaining six biopsies. Of the four biopsies that showed trace to 1+ staining for IgG, three of these showed trace to 1+ staining of C4d. Few sclerosed glomeruli were noted in the four biopsies with bright C3 and negative C4d staining in the nonsclerosed glomeruli; the sclerosed glomeruli were also negative for C4d. Representative immunofluorescence findings are shown in Figure 2. A patient with recurrent DDD showed bright C3 with negative C4d staining. Representative biopsy findings of this patient are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

C3 and C4d staining in C3 GN. Top panel shows staining for C3, and bottom panel shows staining for C4d. Each vertical panel represents one patient: (A) and (E), (B) and (F), (C) and (G), and (D) and (H) represent one patient of C3 GN.

Figure 3.

DDD. (A) Periodic acid–Schiff stain showing MPGN with mesangial expansion, increased mesangial cellularity, thickened capillary walls, and double contour formation (40×). Immunofluorescence showing (B) bright staining for C3 in the mesangium and along the capillary walls (40×) and (C) completely negative staining for C4d. (D) Electron microscopy showing dense deposits along the glomerular basement membranes and in the mesangium (2900×).

C4d studies were also performed on two biopsies that were consistent with C3 GN, but the patients had an ill-defined autoimmune disease with positive antinuclear factor (ANA) titers. In one patient, tubular reticular inclusions were noted in endothelial cells on electron microscopy. Both patients showed bright staining for C3, with less intense but positive staining for 1–2+ C4d and 1+ IgG. The findings are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

C4d staining in C3GN in the setting of an autoimmune disease

| Patient | Pathology Diagnosis | C4d | C3 | C1q | Ig | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mesangioproliferative GN | 2 | 3 | 0 | IgG 1+ | + ANA + dsDNA |

| 2 | MPGN/C3 GN | 1–2 | 3 | 1 | IgG 1+ | + ANA TRIS |

ds, double stranded; TRIS, tubular reticular inclusions.

Glomerular C4d Staining in Postinfectious GN

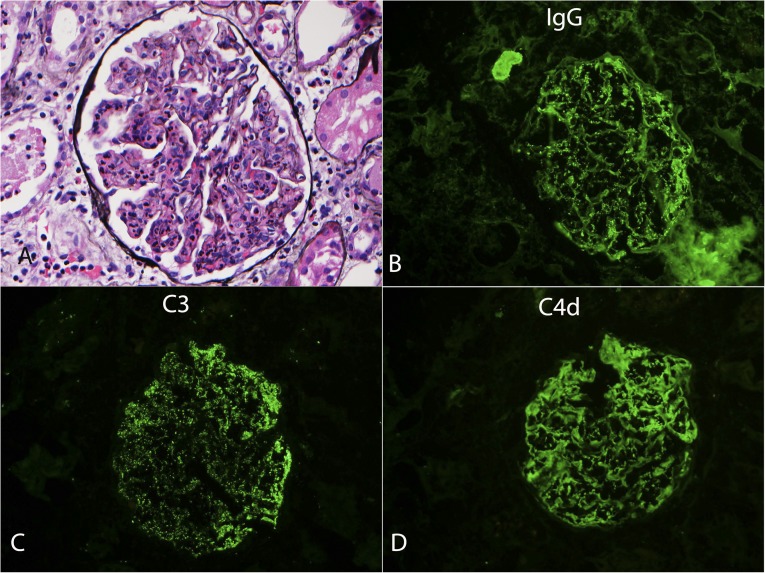

For comparison, we selected 13 biopsies of postinfectious GN. The immunofluorescence findings are shown in Table 4. All biopsies showed bright staining for C3. Eight biopsies were positive for Igs. There was mild 1+ C1q staining in two biopsies. Six biopsies were completely negative for C4d, six biopsies showed 1–2+ staining for C4d, and only one biopsy showed 3+ staining for C4d. Interestingly, out of the 6 biopsies that were negative for C4d, four showed no Ig, whereas two showed 1+ IgG staining. Of the six biopsies that showed 1–2+ C4d staining, all biopsies were commensurate with the Ig staining: five showed 1–2+ Ig staining, whereas one showed 3+ Ig. The single biopsy with 3+ C4d staining also showed 3+ IgG staining. The biopsy findings of this patient (patient 1) are presented in Figure 4.

Table 4.

C4d staining in postinfectious GN

| Patient | Pathology Diagnosis | C4d | C3 | C1q | Ig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Postinfectious GN (streptococci) | 3 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+, IgA 1+, IgM 1+ |

| 2 | Postinfectious GN (foot ulcer) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Postinfectious GN (foot ulcer/osteomyelitis) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Postinfectious GN (Staphylococcus) | 1 | 3 | 0 | κ 1, λ 1+ |

| 5 | Postinfectious GN (Staphylococcus) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Postinfectious GN (Staphylococcus) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | Postinfectious GN (streptococci) | 0 | 3 | 1+ | IgG 1+ |

| 8 | Postinfectious GN (URI) | 1–2 | 3 | 0 | IgG 1–2+ |

| 9 | Postinfectious GN (URI) | 1–2 | 3 | 1+ | IgG 2+ |

| 10 | Postinfectious GN (streptococci) | 0 | 3 | 0 | IgG 1+ |

| 11 | Postinfectious GN (streptococci) | 1 | 3 | 0 | IgA 1+, IgG 2+ |

| 12 | Postinfectious GN (Staphylococcus) | 2 | 3 | 0 | IgG 3+ |

| 13 | Postinfectious GN (Staphylococcus) | 1 | 2 | 0 | IgA 2+ |

URI, upper respiratory infection.

Figure 4.

Postinfectious GN. (A) Silver methenamine stain showing a glomerulus with diffuse endocapillary proliferative pattern of injury (40×). Immunofluorescence showing granular staining for IgG (B), C3 (C), and C4d (D) (40×).

Discussion

In this article, we set out to study the value of glomerular C4d staining in the diagnosis of C3 glomerulopathy and immune complex-mediated GN. We found that glomerular staining for C4d is positive in patients with immune complex-mediated GN, except for IgA nephropathy. On the other hand, C4d is negative in 80% of patients with C3 glomerulopathy, with the remaining patients showing only trace/1+ C4d staining, clearly distinct from the bright C4d present along with the Ig and C3 in immune complex-mediated GN.

We chose 18 biopsies of immune complex-mediated GN representing the three main categories (i.e., autoimmune diseases, chronic infections, monoclonal gammopathy). C1q staining was seen in immune complex-mediated GN secondary to autoimmune diseases. In our patients, C1q was negative in immune complex-mediated GN secondary to monoclonal gammopathy or infections. On the other hand, C4d was positive and mirrored the Ig and C3 staining in all three settings. There was bright C4d staining in fibrillary GN. C4d has previously been shown to be a marker for early recurrent membranous nephropathy.19 In our study, all four biopsies of membranous nephropathy were positive for C4d. C4d was also positive in all instances of lupus nephritis and in all instances of MPGN secondary to immune-complex deposition, including monoclonal Ig, hepatitis C, and autoimmune disease. Furthermore, one biopsy (patient 13) showed an MPGN with weak staining for IgG κ and bright staining for C3. This raised the question whether the MPGN was the result of deposition of monoclonal Ig or C3 glomerulopathy. The biopsy showed bright C4d staining, indicating activation of LP/CP by the monoclonal Ig and confirming the diagnosis of MPGN secondary to the monoclonal Ig. Subsequent immunofluorescence after pronase digestion of paraffin-embedded material also revealed monoclonal IgG κ (2+ each). Therefore, in all of these patients, the positive C4d staining signifies activation of the CP or LP of complement that likely contributes to the inflammatory process.

In one patient with chronic MPGN, there was only mildly positive staining for C4d, suggesting that in patients with chronic and sclerosing GN there is negative or minimal ongoing activation of the CP of complement.

The only negative C4d staining in immune-complex mediated GN was noted in two biopsies of IgA nephropathy, in line with previous reports,11 and consistent with the activation of the AP in IgA nephropathy. Nevertheless, a small proportion may show positive C4d staining as a sign of LP activation and is predictive of a poorer prognosis in these patients.11

We chose 30 biopsies of C3 glomerulopathy, of which 25 biopsies showed C3 GN and five showed DDD. C4d was negative in 24 (80%) of the 30 biopsies of C3 glomerulopathy. Of the remaining six biopsies, three (10%) showed trace and three (10%) showed 1+ staining for C4d. The mild C4d staining was in the same location as the bright C3. C4d was negative in all five patients with DDD, therefore distinguishing the biopsies from the recently described C4 DDD in which C4d is brightly positive.12 Therefore, a negative C4d serves as a marker for DDD as well. None of the biopsies of C3 glomerulopathy showed the bright 2–3+ C4d staining noted in immune complex-mediated GN.

Of the six C3 GN biopsies that showed trace to 1+ staining for C4d, three biopsies also showed mild to 1+ staining for IgG. This raises the possibility that immune complexes, such as in the setting of remote postinfectious GN, act as a trigger for C3 glomerulopathy in a small number of patients.23 Furthermore, biopsies from two patients with ill-defined autoimmune diseases (positive ANA titers, but negative evaluation for lupus) showed bright 3+ C3, 1+ IgG, and 1–2+ C4d. By definition, they are classified as C3 GN on the basis of the bright C3 and minimal IgG, even though it is likely that the autoimmune disease may serve as a trigger for the GN. In such situations, the positive C4d staining confirms CP/LP of complement activation and points to the autoimmune disease as a likely contributing factor.

The characteristic features of postinfectious GN on kidney biopsy are a proliferative GN on light microscopy, bright C3 staining with or without Ig on immunofluorescence, and subepithelium-like deposits called humps on electron microscopy.24–26 Therefore, kidney biopsy findings of postinfectious GN and C3 GN share common features. We performed C4d staining in 13 biopsies of postinfectious GN to determine whether it would be useful in differentiating the two conditions. We found six biopsies of postinfectious GN that were negative for C4d staining, therefore mirroring the findings of C3 GN. It is possible that these patients represent a subset of postinfectious GN that may actually represent C3 GN or postinfectious GN in which the AP is activated (atypical postinfectious GN).23,27 Further evaluation of the AP may be justified in these patients to determine whether an underlying abnormality is present. In the remaining seven biopsies, there was mild (1–2+) staining for C4d in six patients and bright (3+) C4d in one biopsy. In general, these biopsies also showed mild staining for Ig (1–2+) in five biopsies and bright staining of Ig (3+) in two biopsies, suggesting that C4d staining in these patients is likely caused by CP activation by immune complexes. Alternatively, LP activation by the microbial pathogens may contribute to C4d staining in these patients. Clearly, further studies are required to validate these preliminary findings.

The sensitivity and specificity of negative (or trace) C4d versus negative C1q versus negative Ig on immunofluorescence for the diagnosis of C3 glomerulopathy (30 patients) were compared with immune complex-mediated GN, excluding IgA nephropathy and postinfectious GN in which AP activation likely plays a role. The sensitivity and specificity for negative C4d in C3 glomerulopathy were 93% and 100% versus 97% and 63% for negative C1q versus 87% and 100% for negative Ig, respectively. The results show that although the sensitivity of negative C4d for the diagnosis C3 glomerulopathy is slightly lower than negative C1q, the specificity is much higher (100% versus 63%). Compared with negative staining for Ig, negative staining for C4d has a higher sensitivity but similar specificity. These data suggest that staining for C4d is valuable in differentiating C3 glomerulopathy from immune complex-mediated GN.

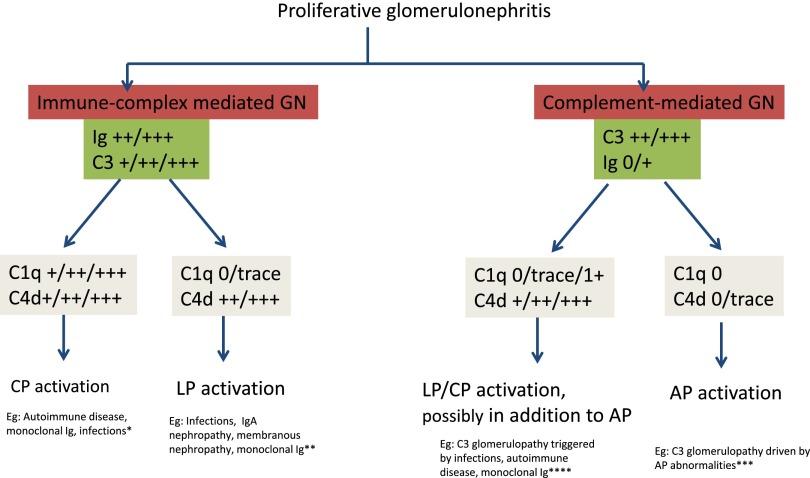

The role of C4d and C1q staining in determining the type of complement activation in proliferative GN is proposed in Figure 5. Immune complex-mediated GN is characterized by the presence of immune complexes/Ig and C3. In immune complex-mediated GN, the presence of both C1q and C4d is typical of CP activation. C1q is seen in the setting of autoimmune diseases, and in some instances is seen in monoclonal gammopathy-associated (60%, mild with an average intensity of 1.2+) and infection-associated GN (36%, weak with an average intensity of 0.8).28,29 On the other hand, the presence of C4d in the absence of C1q may indicate a role for LP activation in immune complex-mediated GN, such as IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, and in some instances of monoclonal gammopathy and infection-associated GN. Complement-mediated GN is characterized by the presence of bright C3 and negative/scant Ig. The absence of C1q and C4d in complement-mediated GN indicates C3 glomerulopathy via AP activation alone. On the other hand, the presence of C4d (and absent C1q) in the setting of complement-mediated GN, as seen in C3 glomerulopathy occurring in patients with infections/autoimmune disease/monoclonal gammopathy, likely indicates a role for LP and AP activation.23,30 Also, bright C3 and positive C4d staining in C3 glomerulopathy (with negative routine immunofluorescence studies for Ig) may suggest masked immune deposits (as in patient 13) and indicate further studies, such as repeat immunofluorescence after pronase digestion of the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue or proteomics by laser dissection and mass spectrometry.31–33 Finally, the presence of C1q in addition to C4d, although not seen in any of our patients, in the setting of C3 glomerulopathy may indicate a role for CP as well.

Figure 5.

Proposed role of C4d and C1q in the diagnosis of proliferative GN. Immune complex-mediated GN that shows both C1q and C4d indicate CP activation, whereas those that show only C4d and negative C1q indicate LP activation. Complement-mediated GN showing negative C4d and C1q indicates AP activation, whereas those showing negative/trace C1q and positive C4d likely indicate a role for LP and AP activation as well. *Most instances of immune complex-mediated GN with positive C1q and C4d, indicating CP activation, are caused by autoimmune diseases; however, many patients with monoclonal Ig are also positive for C1q. **Some instances of infections, IgA nephropathy, and membranous nephropathy are negative for C1q but positive for C4d and indicate LP activation. ***Most patients with complement-mediated GN are negative for C1q and C4d. These form the bulk of complement-mediated GN and indicate AP activation only. ****In a small minority of complement-mediated GN, there is staining for C4d with no staining for C1q, suggesting LP activation. This is likely caused by association of infections, autoimmune diseases, or monoclonal Ig act as a trigger for complement-mediated GN. On the other hand, this may also indicate masked immune deposits, indicating further studies, such as immunofluorescence after pronase digestion or laser dissection followed by proteomic analysis to identify the masked deposits. In our study, only one out of 30 patients with complement-mediated GN showed C1q.

A caution in interpretation of C4d staining is required because mild nonspecific/normal mesangial C4d may be present, particularly in the transplant setting. However, as shown in our studies, there are quantitative and qualitative differences present. Therefore, the C4d staining in immune complex GN is usually bright and mirrors the Ig and C3 both in location and intensity. On the other hand, in C3 glomerulopathy, C4d is negative (or shows minimal mesangial staining) in the presence of bright C3. This is in contrast with the minimal background mesangial C4d staining seen in a transplant kidney or native kidney. To illustrate this point, C3 and C4d staining are shown in different situations, such as protocol transplant biopsy, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, minimal change disease, and thin basement membrane disease (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

To summarize, we show that negative C4d staining is an important ancillary study in the diagnosis of C3 glomerulopathy, whereas positive C4d staining serves as a marker for immune complex-mediated GN. Therefore, the C4d stain helps to determine whether the proliferative GN is mediated by the activation of the AP or the activation of the CP/LP. The final confirmation of C3 glomerulopathy should be on the basis of the kidney biopsy findings along with evaluation of the AP of complement. Because C4d staining is routinely available in almost every pathology laboratory, it may become an important tool to unravel the underlying etiology in proliferative GN.

Concise Methods

Immune complex and complement-mediated GN were identified by retrospective review of kidney biopsies. We identified 18 biopsies of immune complex-mediated GN and 30 biopsies of C3 glomerulopathy. We also identified two patients with C3 glomerulopathy with underlying ill-defined autoimmune disease and 13 patients with postinfectious GN. Light microscopy material was available for review in all patients. The slides had been stained with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, Masson’s trichrome, and Jones methenamine silver. Immunofluorescence included staining for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, κ, λ, fibrinogen, albumin, and C4d using polyclonal FITC-conjugated antibodies (all antibodies except C4d [Dako] and C4d-AbD [Serotec]). Immunofluorescence was scored on a 0 to 3+ scale. For immune complex-mediated GN we chose recent patients (November 2013–2014), except for one (March 2013), so that immunofluorescence material was available for review. For C3 glomerulopathy we chose both recent and archived patients that were previously reported.6 In all patients, we repeated immunofluorescence for C3 and C4d staining. Trace glomerular IgM was counted as nonspecific. Electron microscopy was performed in all patients.

Staining for C4d

Immunofluorescence was done using the Dako autostainer (Carpinteria, CA). Tissue was received in Zeus fixative and put through a 30-minute wash with frequent gentle agitation using at least 20 ml of Dako Zeus wash solution. The excess solution was removed by placing in a blot, and the tissue was snap frozen in a cryostat for microtome sectioning. Frozen tissue was used, and 4-μm thick sections were cut on charged slides. C4d staining was then performed on the autostainer as follows: the sections are washed with Dako wash buffer for 5 minutes followed by incubating with the primary antibody (C4d primary antibody at 1:200 dilution) for 15 minutes. This was followed by another buffer wash for 5 minutes, labeling with the secondary antibody (FITC-labeled rabbit anti-mouse) for 15 minutes, and two buffer washes for 5 minutes each. In our laboratory, a positive C1q and C4d (C4d secondary antibody at 1:20 dilution) control is run at the beginning of each day and serves as the daily positive control. A C4d negative control is performed by omitting the primary antibody.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “C4d Staining in the Diagnosis of C3 Glomerulopathy,” on pages 2609–2611.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014040406/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sethi S, Fervenza FC: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: Pathogenetic heterogeneity and proposal for a new classification. Semin Nephrol 31: 341–348, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sethi S, Fervenza FC: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis--a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med 366: 1119–1131, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sethi S. Etiology-based diagnostic approach to proliferative glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 561–566, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Servais A, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Lequintrec M, Salomon R, Blouin J, Knebelmann B, Grünfeld JP, Lesavre P, Noël LH, Fakhouri F: Primary glomerulonephritis with isolated C3 deposits: A new entity which shares common genetic risk factors with haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J Med Genet 44: 193–199, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sethi S, Fervenza FC, Zhang Y, Nasr SH, Leung N, Vrana J, Cramer C, Nester CM, Smith RJ: Proliferative glomerulonephritis secondary to dysfunction of the alternative pathway of complement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1009–1017, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sethi S, Fervenza FC, Zhang Y, Zand L, Vrana JA, Nasr SH, Theis JD, Dogan A, Smith RJ: C3 glomerulonephritis: Clinicopathological findings, complement abnormalities, glomerular proteomic profile, treatment, and follow-up. Kidney Int 82: 465–473, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale DP, de Jorge EG, Cook HT, Martinez-Barricarte R, Hadjisavvas A, McLean AG, Pusey CD, Pierides A, Kyriacou K, Athanasiou Y, Voskarides K, Deltas C, Palmer A, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, de Cordoba SR, Maxwell PH, Pickering MC: Identification of a mutation in complement factor H-related protein 5 in patients of Cypriot origin with glomerulonephritis. Lancet 376: 794–801, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickering MC, D’Agati VD, Nester CM, Smith RJ, Haas M, Appel GB, Alpers CE, Bajema IM, Bedrosian C, Braun M, Doyle M, Fakhouri F, Fervenza FC, Fogo AB, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Gale DP, Goicoechea de Jorge E, Griffin G, Harris CL, Holers VM, Johnson S, Lavin PJ, Medjeral-Thomas N, Paul Morgan B, Nast CC, Noel LH, Peters DK, Rodríguez de Córdoba S, Servais A, Sethi S, Song WC, Tamburini P, Thurman JM, Zavros M, Cook HT: C3 glomerulopathy: Consensus report. Kidney Int 84: 1079–1089, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen CP, Walker PD: Redefining C3 glomerulopathy: ‘C3 only’ is a bridge too far. Kidney Int 83: 331–332, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou J, Markowitz GS, Bomback AS, Appel GB, Herlitz LC, Barry Stokes M, D’Agati VD: Toward a working definition of C3 glomerulopathy by immunofluorescence. Kidney Int 85: 450–456, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinosa M, Ortega R, Sánchez M, Segarra A, Salcedo MT, González F, Camacho R, Valdivia MA, Cabrera R, López K, Pinedo F, Gutierrez E, Valera A, Leon M, Cobo MA, Rodriguez R, Ballarín J, Arce Y, García B, Muñoz MD, Praga M, Spanish Group for Study of Glomerular Diseases (GLOSEN) : Association of C4d deposition with clinical outcomes in IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 897–904, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sethi S, Sullivan A, Smith RJ: C4 dense-deposit disease. N Engl J Med 370: 784–786, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohsawa I, Ohi H, Endo M, Fujita T, Matsushita M, Fujita T: Evidence of lectin complement pathway activation in poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 56: 1158–1159, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins AB, Schneeberger EE, Pascual MA, Saidman SL, Williams WW, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Cosimi AB, Colvin RB: Complement activation in acute humoral renal allograft rejection: Diagnostic significance of C4d deposits in peritubular capillaries. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2208–2214, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen D, Colvin RB, Daha MR, Drachenberg CB, Haas M, Nickeleit V, Salmon JE, Sis B, Zhao MH, Bruijn JA, Bajema IM: Pros and cons for C4d as a biomarker. Kidney Int 81: 628–639, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batal I, Chalasani G, Wu C, Shapiro R, Bastacky S, Randhawa P: Deposition of complement product C4d in anti-glomerular basement membrane glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 1098–1101, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batal I, Liang K, Bastacky S, Kiss LP, McHale T, Wilson NL, Paul B, Lertratanakul A, Ahearn JM, Manzi SM, Kao AH: Prospective assessment of C4d deposits on circulating cells and renal tissues in lupus nephritis: A pilot study. Lupus 21: 13–26, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusunoki Y, Itami N, Tochimaru H, Takekoshi Y, Nagasawa S, Yoshiki T: Glomerular deposition of C4 cleavage fragment (C4d) and C4-binding protein in idiopathic membranous glomerulonephritis. Nephron 51: 17–19, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez EF, Cosio FG, Nasr SH, Sethi S, Fidler ME, Stegall MD, Grande JP, Fervenza FC, Cornell LD: The pathology and clinical features of early recurrent membranous glomerulonephritis. Am J Transplant 12: 1029–1038, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhir V: Is cellular C4d a good biomarker for SLE nephritis? Lupus 21: 1036, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xing GQ, Chen M, Liu G, Zheng X, E J, Zhao MH: Differential deposition of C4d and MBL in glomeruli of patients with ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Clin Immunol 30: 144–156, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MK, Maeng YI, Lee SJ, Lee IH, Bae J, Kang YN, Park BT, Park KK: Pathogenesis and significance of glomerular C4d deposition in lupus nephritis: Activation of classical and lectin pathways. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 6: 2157–2167, 2013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sethi S, Fervenza FC, Zhang Y, Zand L, Meyer NC, Borsa N, Nasr SH, Smith RJ: Atypical postinfectious glomerulonephritis is associated with abnormalities in the alternative pathway of complement. Kidney Int 83: 293–299, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montseny JJ, Meyrier A, Kleinknecht D, Callard P: The current spectrum of infectious glomerulonephritis. Experience with 76 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 74: 63–73, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nadasdy T, Hebert LA: Infection-related glomerulonephritis: Understanding mechanisms. Semin Nephrol 31: 369–375, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasr SH, Fidler ME, Valeri AM, Cornell LD, Sethi S, Zoller A, Stokes MB, Markowitz GS, D’Agati VD: Postinfectious glomerulonephritis in the elderly. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 187–195, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolas C, Vuiblet V, Baudouin V, Macher MA, Vrillon I, Biebuyck-Gouge N, Dehennault M, Gié S, Morin D, Nivet H, Nobili F, Ulinski T, Ranchin B, Marinozzi MC, Ngo S, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Pietrement C: C3 nephritic factor associated with C3 glomerulopathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol 29: 85–94, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasr SH, Satoskar A, Markowitz GS, Valeri AM, Appel GB, Stokes MB, Nadasdy T, D’Agati VD: Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2055–2064, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nasr SH, Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Said SM, Valeri AM, D’Agati VD: Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis in the modern era: Experience with 86 adults and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 87: 21–32, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zand L, Kattah A, Fervenza FC, Smith RJ, Nasr SH, Zhang Y, Vrana JA, Leung N, Cornell LD, Sethi S: C3 glomerulonephritis associated with monoclonal gammopathy: A case series. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 506–514, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen CP, Ambuzs JM, Bonsib SM, Boils CL, Nicholas Cossey L, Messias NC, Silva FG, Wang YH, Gokden N, Walker PD: Membranous-like glomerulopathy with masked IgG kappa deposits. Kidney Int 86: 154–161, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasr SH, Galgano SJ, Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, D’Agati VD: Immunofluorescence on pronase-digested paraffin sections: A valuable salvage technique for renal biopsies. Kidney Int 70: 2148–2151, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sethi S, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Dogan A: Mass spectrometry based proteomics in the diagnosis of kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 22: 273–280, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.