Abstract

Cell death and inflammation in the proximal tubules are the hallmarks of cisplatin-induced AKI, but the mechanisms underlying these effects have not been fully elucidated. Here, we investigated whether necroptosis, a type of programmed necrosis, has a role in cisplatin-induced AKI. We found that inhibition of any of the core components of the necroptotic pathway—receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1), RIP3, or mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL)—by gene knockout or a chemical inhibitor diminished cisplatin-induced proximal tubule damage in mice. Similar results were obtained in cultured proximal tubular cells. Furthermore, necroptosis of cultured cells could be induced by cisplatin or by a combination of cytokines (TNF-α, TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis, and IFN-γ) that were upregulated in proximal tubules of cisplatin-treated mice. However, cisplatin induced an increase in RIP1 and RIP3 expression in cultured tubular cells in the absence of cytokine release. Correspondingly, overexpression of RIP1 or RIP3 enhanced cisplatin-induced necroptosis in vitro. Notably, inflammatory cytokine upregulation in cisplatin-treated mice was partially diminished in RIP3- or MLKL-deficient mice, suggesting a positive feedback loop involving these genes and inflammatory cytokines that promotes necroptosis progression. Thus, our data demonstrate that necroptosis is a major mechanism of proximal tubular cell death in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxic AKI.

Keywords: necroptosis, renal proximal tubule cell, cisplatin nephrotoxicity

Cisplatin is a highly effective chemotherapy drug used for many types of solid tumors. However, cisplatin treatment is associated with AKI as an adverse effect.1 Cell death and inflammation are found predominantly in the proximal tubule segment of the nephron, which coincides with the location of maximal cisplatin accumulation.2,3 Morphologic analysis of cisplatin nephrotoxicity shows that most cellular damage in kidney tubules is caused by necrosis.4,5 However, many previous studies have focused on apoptosis induced by cisplatin in renal tubular cells, perhaps because necrosis has long been considered to be an incidental and uncontrolled form of cell death.6,7 Several genes, such as the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and the proapoptotic gene Bax, play important roles in cisplatin-induced AKI.7,8 However, induction of p53 and PUMAα has also been shown to be involved in cisplatin-induced renal tubular apoptosis but is not required for AKI.9 Multiple cell death pathways appear to be involved in cisplatin nephrotoxicity, but the underlying mechanisms are still largely unknown.

In recent years, substantial progress has been made in our understanding of necroptosis, a type of programmed necrosis. Necroptosis can be induced in cells with high levels of receptor interacting-protein 3 (RIP3).10 Signals from different death stimuli may be transduced to RIP1 via different routes.11 The RIP1 then can recruit RIP3 through RIP homotypic interaction motif (RHIM) domain mediated–interactions.12 This RIP1-RIP3 hetero-interaction promotes RIP3-RIP3 homo-interactions, leading to the recruitment of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) and phosphorylation of MLKL.13 Phosphorylated MLKL forms tetramers and translocates onto the plasma membrane to form higher-ordered complexes, resulting in ion influx and eventual plasma membrane disruption.14–16

Necroptosis is involved in various pathologic conditions, including antiviral responses, acute pancreatitis, atherosclerosis, and drug-induced liver injury.12,17,18 Here we studied the role of necroptosis in cisplatin-induced AKI. We found that blockade of necroptosis by deletion of the RIP3 or MLKL genes in mice, or administration of the RIP1 inhibitor necrostatin (Nec)-1 protected mice from cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, suggesting an important role of necroptosis in cisplatin-induced AKI. We also demonstrated that necroptosis is associated not only with the direct cytotoxicity induced by cisplatin but also the upregulation of necroptotic and proinflammatory genes in cisplatin-treated renal tubules. The latter phenomenon can further promote necroptosis of renal proximal tubular cells (PTCs), demonstrating a positive feedback relationship between necroptosis and inflammation. Thus, necroptosis appears to be the major cause of the massive renal tubule damage in cisplatin-induced AKI.

Results

Necroptosis Contributes to Cisplatin-Induced AKI

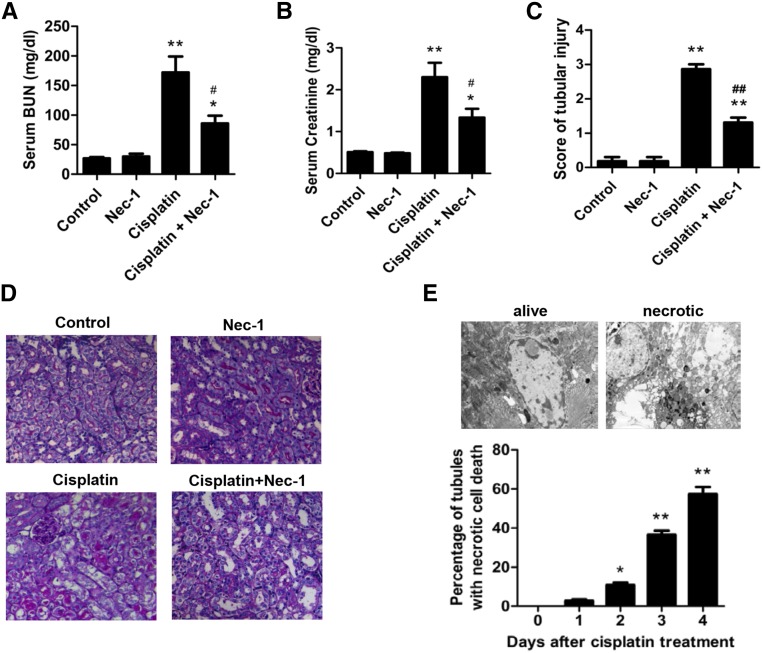

To determine the contribution of necroptosis to cisplatin-induced AKI in mice, we investigated the effects of blocking necroptosis with the RIP1 inhibitor Nec-1. Elevations in the serum concentrations of creatinine and BUN, which indicate the loss of kidney function, were significantly inhibited in Nec-1–treated mice (Figure 1, A and B). Histologic analysis with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining revealed that many necrotic proximal tubular cells in the cisplatin-treated renal cortex were reduced by Nec-1 treatment (Figure 1, C and D). This result was further confirmed by electron microscope analysis (Figure 1E). While our research was in progress, Linkermann et al. reported a study of necroptosis in ischemia-reperfusion injury of kidney, which showed that Nec-1 attenuated cisplatin-induced AKI.5 A recent report also showed that the prevention of apoptosis in proximal tubules did not attenuate cisplatin-induced kidney dysfunction.9 When these findings are taken together, we concluded that necroptosis occurs in cisplatin-treated mice and contributes to tubular damage in cisplatin-induced AKI.

Figure 1.

Necroptosis contributes to cisplatin-induced nephrotoxity. (A–E) Male C57BL/6 mice underwent intraperitoneal injection with vehicle or 20 mg/kg cisplatin (n=8). All mice received 250 µl total volume of PBS with DMSO or 1.65 mg/kg Nec-1 every 24 hours. (A and B) Blood samples were collected at day 3 after cisplatin injection to measure BUN and serum creatinine. (C) Histologic damage in the cortex and PAS-stained kidney sections (n=8) was scored by counting the percentage of tubules that displayed tubular necrosis, cast formation, and tubular dilation as follows: 0=normal; 1=<10%; 2=10%–25%; 3=26%–50%; 4=51%–75%; 5=>75%. Ten randomly selected fields (original magnification, ×200) per kidney were used for counting. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus control group; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 versus cisplatin group. (D) Representative images of PAS-stained kidney sections (×200). (E) Representative electron micrographs of proximal renal tubule cells showing that the necrotic cells had nuclear swelling and loss of cell organelle content (original magnification, ×5000) are shown (upper panel). The percentage of proximal tubules containing necrotic cells was evaluated in 30 grid fields (0.236 mm2 per section). Five sections per kidney were used for counting (n=6). Quantifications of proximal tubule percentages with necrotic tubular cells are shown (lower panel). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 compared with day 0.

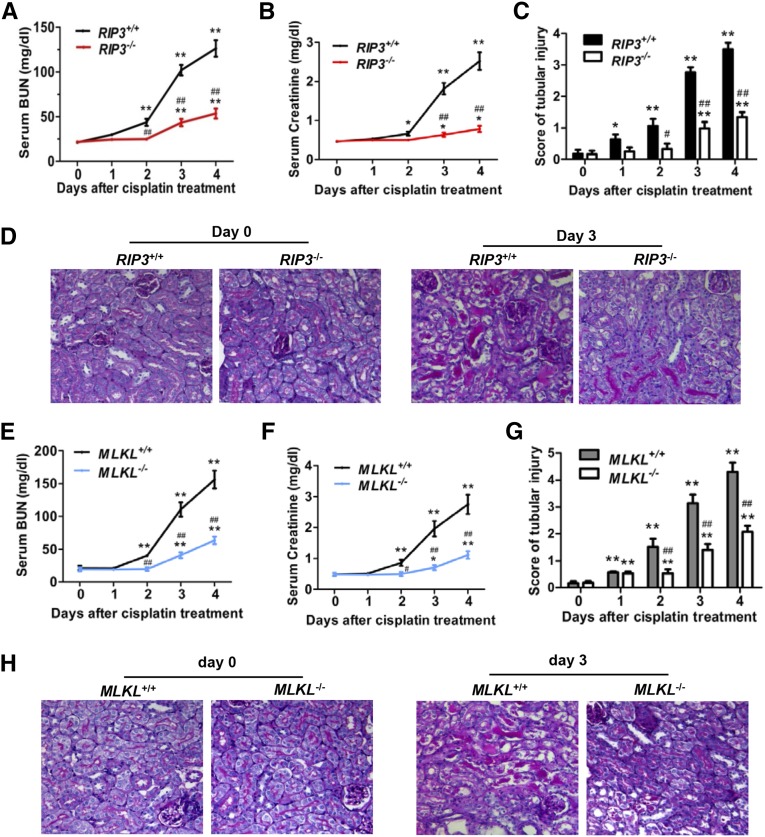

Because RIP3 and MLKL are essential for the necroptosis pathway,10,13,14 we investigated their role in cisplatin-induced AKI. Both RIP3-knockout (KO) and MLKL-KO mice are viable, with no detectable defect in normal development.19,20 The levels of both BUN and serum creatinine were much higher in all wild-type (WT) mice at day 3 and day 4 after cisplatin treatment compared with those in the RIP3−/− and MLKL−/− littermates (Figure 2, A, B, E, and F). Histologic analysis demonstrated that the increase in tubular necrosis, cast formation, and tubular dilation were significantly ameliorated in RIP3−/− mice (Figure 2, C and D) and MLKL−/− mice (Figure 2, G and H). Linkermann et al. also observed that both RIP3 KO and RIP3/caspase-8 double-KO mice survived significantly longer than WT mice in cisplatin-induced AKI.5 Collectively, these data confirmed that necroptosis contributes significantly to cisplatin-induced AKI.

Figure 2.

Cisplatin-induced AKI is attenuated in RIP3-KO and MLKL-KO mice. (A–H) The kidneys and blood samples in mice were harvested at 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 days after treatment with 20 mg/kg cisplatin (n=8). (A, B, E, F) Serum samples were collected for measurements of BUN and serum creatinine levels. (C and G) Histologic damage in the cortex and PAS-stained kidney sections (n=8) was scored by the same evaluation method as shown in Figure 1. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus day 0; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 versus WT. (D and H) Representative images of PAS-stained kidney sections are shown. Original magnification, ×200.

Attenuation of Cisplatin-Induced AKI by Deletion of RIP3 or MLKL Genes Is Independent of Tubular Apoptosis

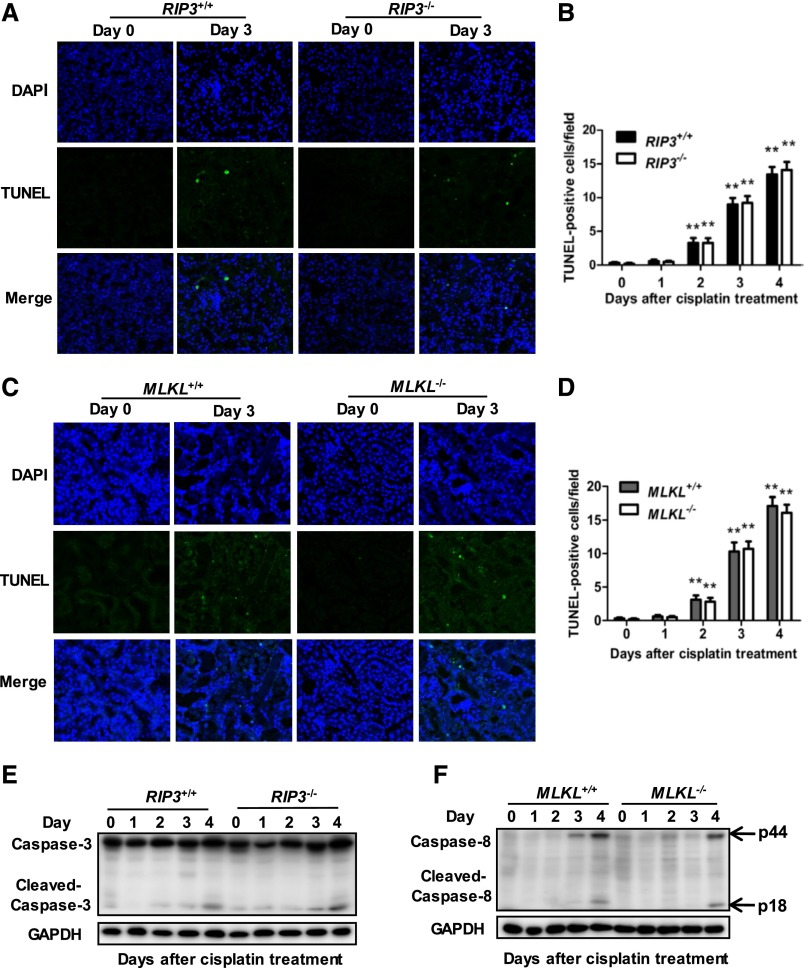

We examined whether RIP3 deficiency affected cisplatin-induced apoptosis in kidney cortical tissues by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated digoxigenin-deoxyuridine nick-end labeling (TUNEL). A small number of TUNEL-positive proximal tubular cells were similarly induced in both RIP3-KO and WT mouse kidneys after cisplatin treatment (Figure 3, A and B). Cleaved caspase-3 was also similarly increased in freshly isolated proximal tubules of both RIP3+/+ and RIP3−/− mice at day 4 after cisplatin treatment (Figure 3E). Therefore, apoptosis did not significantly differ between RIP3+/+ and RIP3−/− mice. Results were similar in experiments performed in MLKL+/+ and MLKL−/− mice (Figure 3, C–D and F). Thus, these observations indicate that attenuation of cisplatin-induced AKI by deletion of RIP3 or MLKL genes is independent of tubular apoptosis.

Figure 3.

RIP3 or MLKL deficiency dose not affect apoptosis in the proximal tubules of kidneys following cisplatin treatment. (A and C) Apoptosis in kidney cortical tissues was examined in TUNEL assays. Representative images of TUNEL staining are shown. Original magnification, ×200. (B and D) TUNEL-positive cells were counted in 10 randomly selected fields (original magnification, ×200) per kidney (n=8 in each group). **P<0.01 versus day 0. (E) Representative Western blot image of cleaved caspase-3 is shown. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase serves as a loading control (n=4). (F) Representative Western blot image of cleaved caspase-8 is shown (n=4).

Cisplatin Induces Necrosis in Primary PTCs Cultured In Vitro

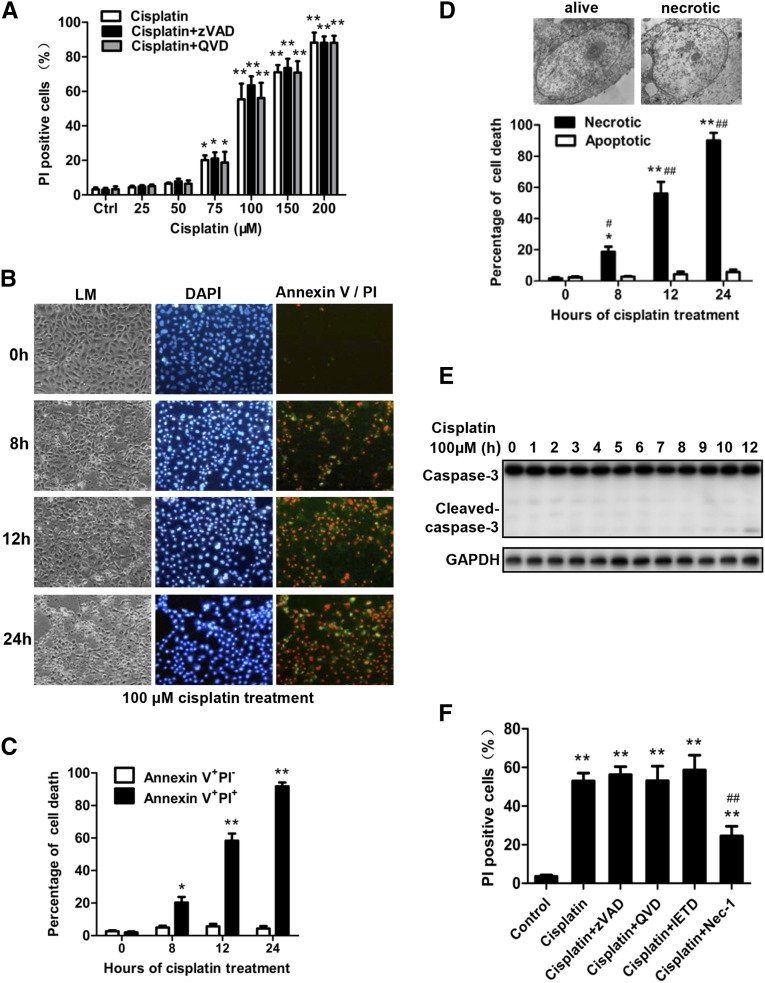

To understand the cellular mechanisms of cisplatin-induced necroptosis of tubular cells, we isolated PTCs and studied cisplatin-induced death of PTCs by using the published methods.5,7 We treated PTCs with different concentrations of cisplatin or cisplatin plus pan caspase inhibitor quinoline-Val-Asp(Ome)-CH2-O-phenoxy (QVD) or benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp(OMe)-fluoromethylketone (zVAD) and determined cell death by measuring propidium iodide (PI) uptake, which indicates loss of cell membrane integrity. The percentages of PI-positive PTCs increased markedly after treatment with 100–200 µM cisplatin for 12 hours, and the addition of QVD or zVAD did not affect these results (Figure 4A). Because annexin V was used to detect apoptosis, we costained cisplatin-treated cells with DAPI, annexin V, and PI and analyzed the cells under fluorescence microscope (Figure 4B). Treatment with cisplatin, 100 µM, induced a small amount of annexin V–positive and PI-negative cells and large amount of annexin V and PI double-positive cells (Figure 4, B and C), suggesting that most of these PTCs underwent necrosis rather than apoptosis. This result was confirmed by electron microscope examination (Figure 4D). Consistently, only slight caspase-3 activation could be detected in 100 µM cisplatin–treated PTCs (Figure 4E), and only the RIP1 inhibitor Nec-1 but not caspase inhibitors inhibited cisplatin-induced death of PTCs (Figure 4F). This finding suggests that cisplatin-induced PTC death is primarily due to necroptosis.

Figure 4.

Detection of cisplatin-induced necroptosis in cultured primary PTCs. (A) PTCs from C57BL/6 mice were treated for 12 hours with vehicle control, different dose of cisplatin as indicated or cisplatin plus QVD (20 µM) or zVAD (20 µM). PI-positive cells were determined and shown (n=4 in each group). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus control group. (B) PTCs were treated with 100 µM cisplatin for the indicated time period. Representative contrast phase light microscopic (LM), PI, and annexin V double-stained photographs are shown (original magnification, ×100). Hoechst was used to stain the nuclei (n=4). (C) The percentage of annexin V+ PI− and annexin V+PI+ cells are shown (n=4). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus 0 hours. (D) Representative electron micrographs of live and necrotic PTCs are shown (upper panel). The percentage of necrotic or apoptotic cells among the 200 PTCs counted for each sample is shown (lower panel) (n=4). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus 0 hours. (E) Representative Western blot image of cleaved caspase-3 is shown. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as a loading control. (F) PTCs were treated with 100 µM cisplatin in the presence or absence of 20 µM zVAD, 20 µM QVD, 20 µM IETD (caspase-8 inhibitor), or 30 µM Nec-1 for 12 hours. PI-positive cells were determined and shown (n=4). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus control group; ##P<0.01 versus cisplatin group.

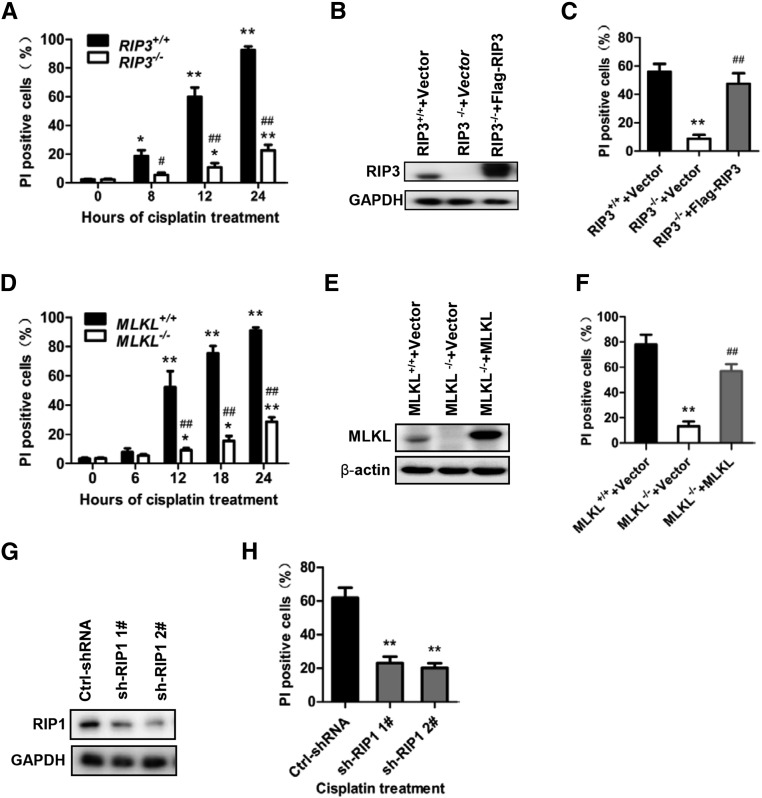

Cisplatin-Induced Necrosis in PTCs Is Controlled via the Necroptotic Pathway

To determine that cisplatin-induced PTC necrosis is necroptosis, we treated PTCs isolated from RIP3+/+, RIP3−/−, MLKL+/+, and MLKL−/− mice with 100 µM cisplatin to induce necrosis. Deletion of RIP3 or MLKL significantly reduced cisplatin-induced PTC necrosis (Figure 5, A and D). To further verify the critical involvement of RIP3 and MLKL in cisplatin-induced necrosis, RIP3−/− and MLKL−/− PTCs were infected with a lentivirus encoding Flag-tagged RIP3 or MLKL to rescue the expression of RIP3 and MLKL, respectively. The reconstitution of RIP3 expression in RIP3−/− cells or MLKL expression in MLKL−/− cells (Figure 5, B and E) restored the sensitivity of the PTCs to cisplatin-induced necrosis (Figure 5, C and F). We could not obtain RIP1−/− PTCs because the mice lacking RIP1 die perinatally. We used small hairpin RNA (shRNA) to knock down RIP1 expression in PTCs to determine the involvement of RIP1 in cisplatin-induced necrosis. Knockdown of RIP1 attenuated cisplatin-induced necrosis in PTCs (Figure 5, G and H).

Figure 5.

Cisplatin-induced necroptosis is RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL dependent. (A) PTCs were isolated from RIP3+/+ and RIP3−/− mice and cultured for use in experiments. Cells were treated with 100 µM cisplatin for the time indicated. The percentage of PI-positive cell at each time-point is shown (n=6). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus 0 hours; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 versus RIP3+/+ group. (B and C) Cells were infected with a lentivirus encoding nothing (vector) or Flag-RIP3 for 36 hours before stimulation with 100 µM cisplatin for 12 hours. RIP3 expression was analyzed by Western blot at 36 hours after infection (B). The percentage of PI-positive PTCs is shown in C (n=4). **P<0.01 versus RIP3+/+ group; ##P<0.01 versus RIP3−/− group. (D) Cells from the MLKL+/+ and MLKL−/− mice were treated with 100 µM cisplatin for indicated time course (n=6). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus 0 hours; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 versus MLKL+/+ group. (E and F) Cells were infected with a lentivirus encoding nothing (vector) or MLKL for 36 hours before stimulation with or without 100 µM cisplatin for 18 hours. MLKL expression is shown in E. Quantification of PI-positive cells is shown in F. **P<0.01 versus MLKL+/+ group; ##P<0.01 versus MLKL−/− group (n=4). (G and H) PTCs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and cultured for experiments (n=4). Cells were infected with a lentiviral vector encoding control or RIP1-shRNAs for 48 hours before stimulation with 100 µM cisplatin for 12 hours. RIP1 expression is shown in G. Quantification of PI-positive cells is shown in hours. **P<0.01 versus control group.

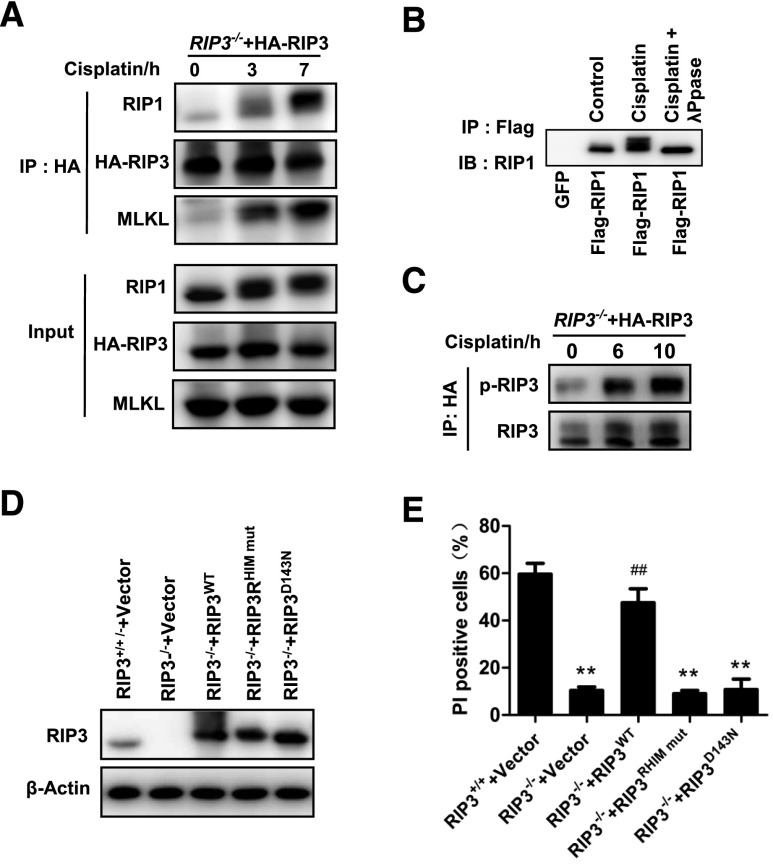

We further examined the involvement of some known necroptotic signal transduction events in cisplatin-induced necroptosis. Because we did not have an antibody that can effectively immunoprecipitate endogenous RIP3, we reconstituted RIP3 expression with HA-RIP3 in RIP3-KO cells, and then used an anti-HA antibody to perform immunoprecipitation of RIP3. As shown in Figure 6A, RIP1 and MLKL were coimmunoprecipitated with RIP3 in PTCs after cisplatin treatment, demonstrating that the formation of necrosomes in cisplatin-treated PTCs. We also observed upward shifts in RIP1 protein bands after cisplatin treatment (Figure 6A), and this band-shift was eliminated by λ-phosphatase treatment (Figure 6B), indicating that RIP1 band-shift was caused by cisplatin-induced phosphorylation. In addition, we detected cisplatin-induced RIP3 phosphorylation, an essential event in necroptosis (Figure 6C). Because the kinase activity of RIP3 and its RHIM domain are required to mediate necroptosis in other cell systems,12,13 we reconstituted WT, RHIM mutant, or kinase dead (D143N) mutant of RIP3 in RIP3-KO PTCs (Figure 6D) and compared their effects on cisplatin-induced necrosis. Only WT RIP3 rescued cisplatin-induced necroptosis in PTCs, while the two mutants did not (Figure 6E), confirming that kinase activity and the RHIM domain of RIP3 are required for cisplatin-induced necroptosis in PTCs. Collectively, our data demonstrated that cisplatin-induced necrosis of PTCs is necroptosis.

Figure 6.

The formation of necrosomes containing RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL is required for cisplatin-induced cell necroptosis in PTCs. (A) PTCs from RIP3−/− mice were infected with HA-RIP3–expressing lentivirus before stimulation with 100 µM cisplatin for the indicated time (n=3). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody (IP: HA) and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-RIP1, anti-RIP3, or anti-MLKL antibodies. Input, 5% of extract before immunoprecipitation (control). (B) PTCs were infected with a lentivirus encoding green fluorescent protein or Flag-RIP1 before stimulation with 100 µM cisplatin for 4 hours (n=3). Immunoprecipitations were performed using M2 beads. The immunoprecipitates were treated with or without λ-phosphatase, and then analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-RIP1 antibody. (C) PTCs from RIP3−/− mice were infected with HA-RIP3–expressing lentivirus and then stimulated with 100 µM cisplatin for the indicated time period (n=3). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody (IP: HA) and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-RIP3 or anti–P-RIP3 antibodies. (D and E) Cells from RIP3−/− mice were infected with a lentivirus encoding nothing (vector) or Flag-RIP3wt, Flag-RIP3RHIM mut, or Flag-RIP3D143N for 36 hours. Cells from RIP3+/+ mice were infected with empty vector. RIP3 expression levels are shown in D by Western blot. All cells were stimulated with 100 µM cisplatin for 12 hours before quantification of PI-positive cells and shown in E (n=4). **P<0.01 versus RIP3+/++vector group; ##P<0.01 versus RIP3−/−+vector group.

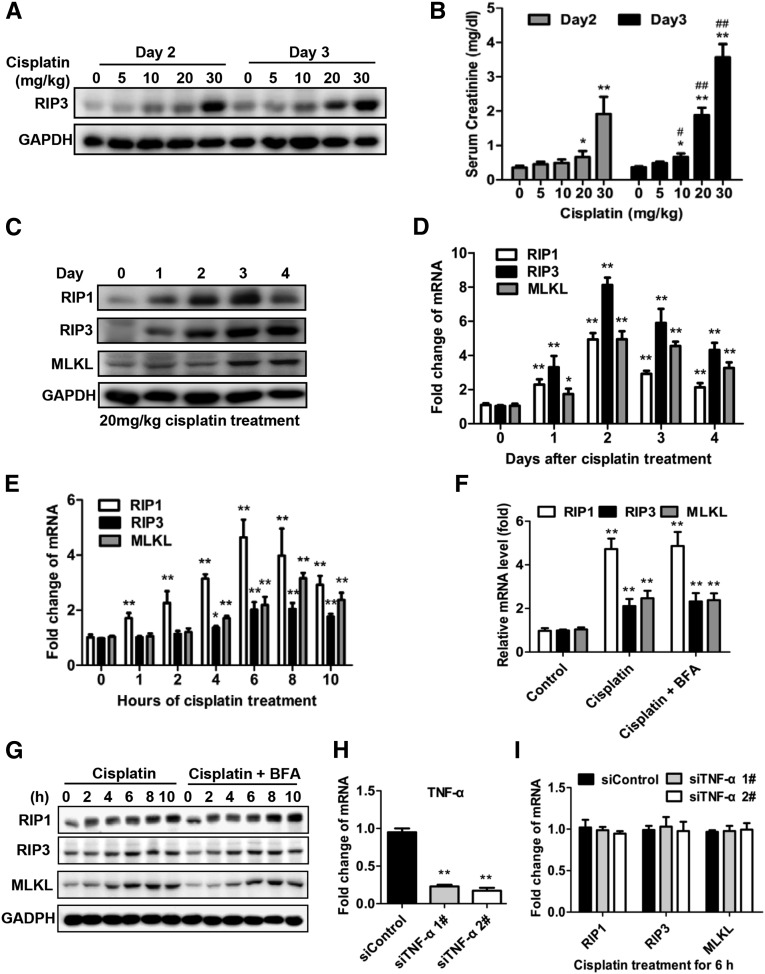

Cisplatin Increases RIP1 and RIP3 Expression in Renal Proximal Tubules

Previous studies have shown that RIP3 expression levels determine the sensitivity of a cell to necroptotic stimuli.10,17 Cisplatin induced a dose-dependent increase in RIP3 protein levels at day 2 and day 3 (Figure 7A), which correlated with the loss of kidney function as indicated by serum creatinine levels (Figure 7B). We further analyzed the levels of RIP1 and MLKL proteins as other core components of the necroptosis pathway. Western blotting analysis revealed an increase in RIP1 protein and a slight elevation in MLKL protein levels (Figure 7C). Real-time PCR analysis also increased in the mRNA levels of these three genes (Figure 7D), although the induction of mRNA levels did not correlate precisely with the protein levels. This discrepancy is most likely to be due to differences in the translation efficiencies of these three proteins.

Figure 7.

RIP1 and RIP3 expression are increased in renal proximal tubules after cisplatin treatment. (A and B) Male C57BL/6 mice underwent intraperitoneal treatment with vehicle or 5–30 mg/kg cisplatin (n=8). Relative expression levels of RIP3 protein in freshly isolated proximal tubules were measured by Western blot (A). Blood samples were collected at day 2 and day 3 after cisplatin injection to measure serum creatinine (B). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus 0 dose group. #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 versus day 2 group. (C and D) Male C57BL/6 mice underwent intraperitoneal treatment with vehicle or 20 mg/kg cisplatin (n=8). Freshly isolated proximal tubules were collected for Western blot (C) and real-time PCR (D) analyses of RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus day 0 group. (E–I) PTCs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and cultured for use in experiments. Cells were treated with 100 µM cisplatin for different time periods (E) or for 6 hours in the presence or absence of 10 µM Brefeldin A and then harvested for real-time PCR (F) and Western blot analyses (G) (n=4). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus control group. (H–I) Effects of TNF-α–specific siRNA on RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL mRNA expression in PTCs treated with cisplatin for 6 hours (n=4). Gene expression levels were normalized to the expression of siControl group in the real-time PCR analysis. **P<0.01 versus siControl group.

We next assessed whether cisplatin could directly induce the expression of RIP1, RIP3, or MLKL in PTCs. In vitro, cisplatin treatment only significantly increased the expression of RIP1 at both the mRNA and protein levels, while the changes in RIP3 and MLKL levels were minor (Figure 7, E and G). It can be speculated that, in vivo, the effective induction of RIP3 could be induced by other stimuli in addition to cisplatin. However, RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL mRNA and protein upregulation was also not inhibited by Brefeldin A–mediated blockade of cytokine secretion (Figure 7, F and G). Furthermore, TNF-α–specific small interfering RNA expression did not reduce the mRNA levels of these three genes (Figure 7, H and I). Thus, cisplatin can directly induce the expression of RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL in PTCs though the patterns and levels of induction in vitro are not the same as those in renal proximal tubules in vivo completely.

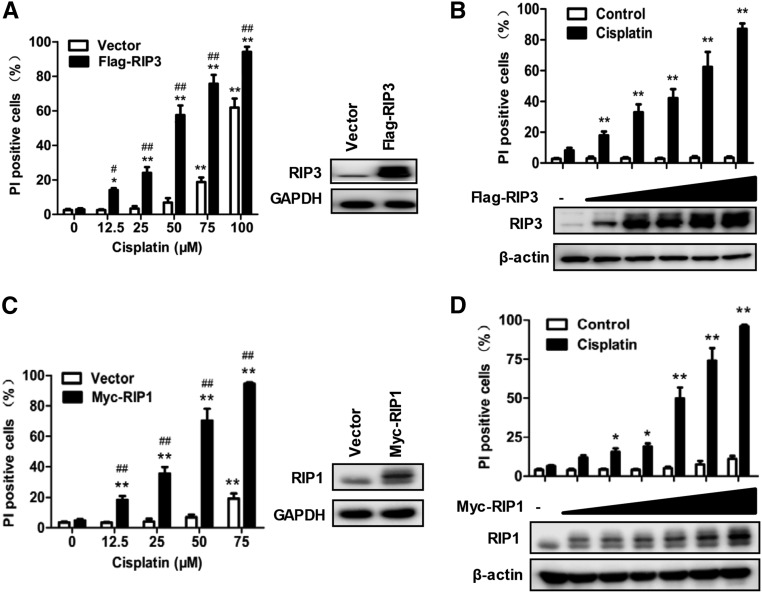

Increase of RIP1 or RIP3 Expression Levels Makes Tubular Cells More Susceptible to Cisplatin-Induced Necroptosis

Figure 4A showed that PTCs underwent necroptosis after high dose cisplatin treatment (>75 μM). Because the increase of RIP3 expression participates in the pathogenesis of some disease models by enhancing necroptosis in vivo,17 we investigated the capacity of the increase of RIP1 and RIP3 in PTCs to enhance the susceptibility to cisplatin-induced necroptosis. The amount of cisplatin-induced necroptosis was significantly increased in RIP3-overexpressing PTCs after Flag-RIP3 transfection (Figure 8A). Furthermore, RIP3-overexpressing PTCs responded more effectively to low-dose cisplatin (Figure 8B). Similarly, RIP1 overexpression also enhanced the sensitivity of PTCs to cisplatin-induced necroptosis (Figure 8, C and D). It is apparent that the increase of RIP1 and RIP3 protein levels during cisplatin-induced AKI contributes to the necroptosis of tubular cells by enhancing their susceptibility to the necroptotic pathway.

Figure 8.

Increased RIP1 or RIP3 expression in PTCs enhances their susceptibility to cisplatin-induced necroptosis. (A) PTCs from male C57BL/6 mice were infected with or without Flag-RIP3–expressing lentivirus for 36 hours and then treated with different does of cisplatin for 12 hours. The PI-positive cells (left panel) and the RIP3 levels (right panel) are shown (n=4). (B) PTCs were infected with different doses of Flag-RIP3–expressing lentivirus for 36 hours and then treated with 50 µM cisplatin for 12 hours. The PI-positive cells (top panel) and the RIP3 levels (bottom panel) are shown (n=4). (C and D) As in A and B except that Myc-RIP1 expression lentivirus was used (n=4). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus 0 µM cisplatin group; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 versus vector group.

Blockade of Necroptotic Pathway Impairs the Induction of Some Proinflammatory Cytokines in Cisplatin-Induced AKI Model

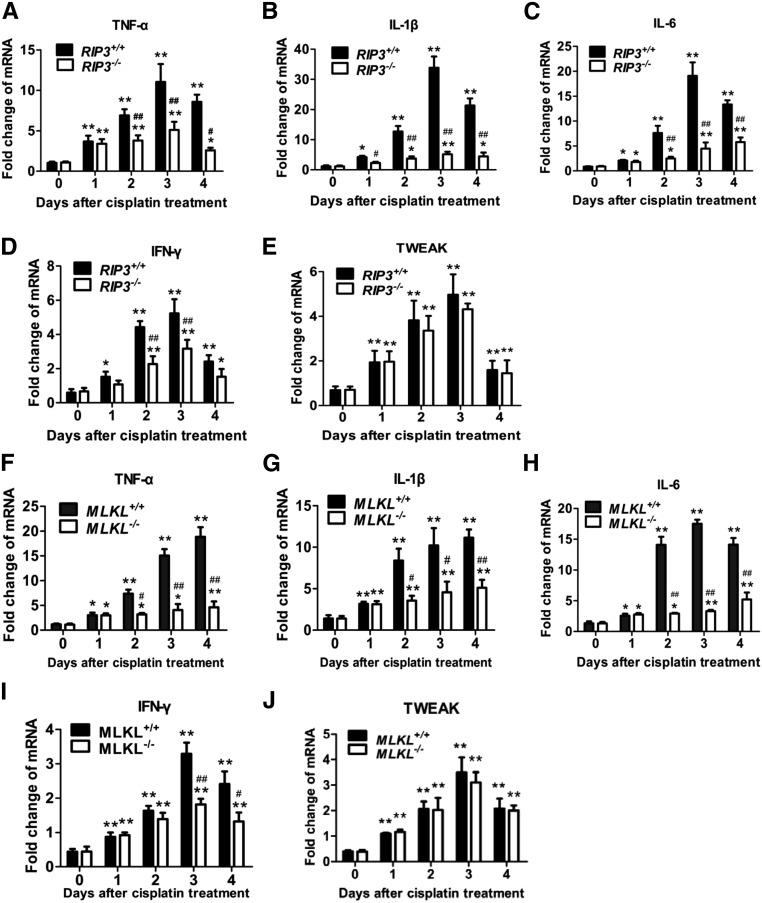

Inflammation in lesions has been shown to play an important role in the acceleration of cisplatin nephrotoxicity.3,21 Cisplatin has been reported to induce cytokine production in renal tubular cells directly,22 and necrotic death may also exacerbate inflammation. Therefore, we investigated whether blocking necroptosis by RIP3 deficiency affects cisplatin-induced inflammatory cytokine expression in proximal tubules in vivo. As reported by others,3,4 the mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) gradually increased in proximal tubules from day 1 to day 4 after cisplatin injection (Figure 9, A–E). While TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IFN-γ transcription levels did not significantly differ between RIP3+/+ and RIP3−/− tubules at day 1, the induction of their mRNA levels in proximal tubules from RIP3+/+ mice were significantly higher than those in RIP3−/− mice in the subsequent days after cisplatin injection (Figure 9, A–D). Similar results were obtained in MLKL+/+ and MLKL−/− mice (Figure 9, F–J). In contrast, deletion of RIP3 and MLKL did not affect cisplatin-induced TWEAK expression (Figure 9, E and J), indicating that factors other than necroptosis-stimulation also influence inflammatory cytokine expression.

Figure 9.

RIP3 or MLKL deficiency reduces many, but not all, inflammatory cytokine levels in proximal tubules of cisplatin-treated mice. (A–E) Proximal tubules from RIP3+/+ and RIP3−/− mice were isolated at 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 days after cisplatin treatment. Relative mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TWEAK were measured by quantitative RT-PCR (n=6). Gene levels were normalized to the expression of β-actin. (F–J) As in A–E except that MLKL+/+ and MLKL−/− mice were used (n=6). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus day 0 group; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 versus WT group.

Both Cisplatin- and Cytokine-Induced PTC Necroptosis Contribute to Cisplatin-Induced AKI

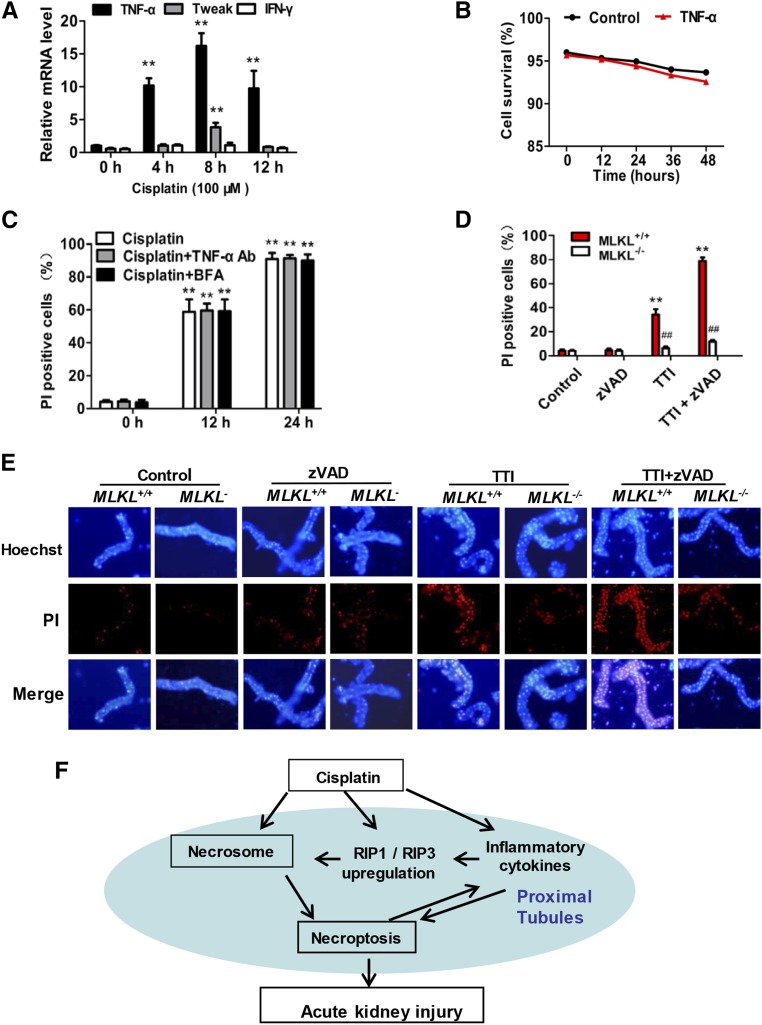

Because cisplatin treatment induces not only PTC necroptosis but also proinflammatory cytokine secretion,22 cisplatin-induced necroptosis might be caused by autocrine of the cisplatin-induced cytokines.23 Co-stimulation of renal tubular cells with a combination of TNF-α, TWEAK, and IFN-γ (referred as TTI) is known to result in caspase-independent cell death or necroptosis.9,24 We analyzed the mRNA levels of TTI in PTCs and found that only TNF-α was significantly induced by cisplatin treatment in vitro (Figure 10A). Therefore, we investigated the requirement for TNF-α and other secreted cytokines in cisplatin-induced necroptosis. TNF-α did not induce PTC death (Figure 10B), and pretreatment with neutralizing anti–TNF-α or Brefeldin A–mediated inhibition of cytokine secretion also did not block cisplatin-induced PTC necroptosis (Figure 10C). Taken together, these observations indicated that cisplatin induces PTC necroptosis directly.

Figure 10.

Necroptosis of renal proximal tubular cells is induced directly by cisplatin and indirectly by a combination of cytokines that are induced in cisplatin-treated mice. (A) PTCs were treated with 100 µM cisplatin for indicated time periods and TNF-α, TWEAK, and IFN-γ levels were measured by real-time PCR (n=4). (B) PTCs were cultured with or without 100 ng/ml recombinant TNF-α for the indicated time periods. Cell survival at each time point is shown (n=4). (C) Cells were treated with cisplatin in the presence or absence of neutralizing TNF-α antibody or Brefeldin A for the indicated time periods. PI-positive cells are shown (n=4). **P<0.01 versus 0 hours. (D) PTCs from MLKL+/+ and MLKL−/− mice were treated with TTI (100 ng/ml TNF-α, 100 ng/ml TWEAK, and 30 U/ml IFN-γ) in the presence or absence of 20 µM zVAD for 24 hours. DMSO was used as vehicle control. PI-positive cells are shown (n=4). **P<0.01 versus control group; ##P<0.01 versus MLKL+/+ group. (E) Freshly isolated renal tubules were cultured for 10 hours in the vehicle control (DMSO), 100 ng/ml recombinant TNF-α, 200 ng/ml TWEAK, and 100 U/ml IFN-γ in the presence or absence of 25 µM zVAD as indicated (n=4). Representative images of PI staining are shown (original magnification, ×100). (F) Proposed model of cisplatin induced-necroptosis.

Interestingly, all these three cytokines (TTI) were increased in proximal tubules of cisplatin-treated mice (Figure 9), so TTI could play a role in triggering tubular cell necroptosis in cisplatin-induced AKI. Indeed, TTI induced PTC death in vitro, which was found to be MLKL-dependent and caspase-independent cell death (Figure 10D), confirming that TTI can induce PTC necroptosis. To further evaluate the role of TTI in inducing necroptosis in AKI, we performed tissue culture of freshly renal proximal tubules isolated from MLKL+/+ or MLKL−/− mice and treated them with TTI in the presence or absence of zVAD. As shown in Figure 10E, 10 hours of TTI treatment markedly increased PI uptake in MLKL+/+ but not in MLKL−/− tubules. zVAD alone had no effect on PI uptake but significantly increased the number of TTI-induced PI-positive cells in renal tubules. Collectively, our data suggest that the necroptotic cell death in renal proximal tubules in cisplatin-treated mice should be induced by both direct cytotoxicity of cisplatin and indirect effects of elevated inflammatory cytokines such as TTI.

Discussion

Cisplatin-induced AKI is associated with renal tubular cell death, inflammation, and tissue injury, which eventually lead to renal dysfunction. Although the molecular mechanism and pathogenesis of cisplatin nephrotoxicity have been studied for many decades, recent evidence has shown that acute necrosis in kidney tubules is the predominant lesion associated with cisplatin-induced AKI.4,5,25 Recent advances in defining the mechanisms of necroptosis10,12–16 led us to use RIP3-KO and MLKL-KO mice to investigate the involvement of necroptosis in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Our data demonstrated that necroptosis of renal tubular cells is essential for cisplatin-induced AKI. Our mechanistic studies suggested that a positive feedback loop consisting of cisplatin-induced necroptosis and necroptosis-triggered inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of AKI (Figure 10F). When cisplatin is administrated in vivo, it accumulates in the renal proximal tubules2 and stimulates necroptosis in some renal tubular cells. The direct induction of necroptosis in some of the tubular cells is due not only to the high local concentration of cisplatin but also the cisplatin-induced increase of RIP1 and RIP3 expression, which enhances necroptotic pathway activity by positive feedback. Necroptotic cell death in the cisplatin-treated kidneys should contribute to the induction of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, TWEAK, and IFN-γ. Such an inflammatory environment contributes significantly to the induction of RIP1 and RIP3 in renal tubular cells in vivo, which, in turn, further facilitates necroptotic signal transduction. Moreover, a combination of TNF-α, TWEAK, and IFN-γ effectively induces necroptosis of tubular cells, with the elevation of these inflammatory cytokines in turn boosting necroptotic pathway activity. Thus, it can be hypothesized that the necroptosis of renal proximal tubular cells in cisplatin-treated mice is induced both directly by cisplatin and indirectly by the cytokine pool containing TNF-α, TWEAK, and IFN-γ.

Cisplatin-induced necroptosis of renal tubular cells was shown to be RIP1, RIP3, and MLKL dependent, thus sharing the same cell death signaling pathway involved in necroptosis in multiple cell systems. However, how RIP1 receives the signals from cisplatin is unknown. Furthermore, although in our study the induction of RIP1 expression by cisplatin treatment is known to increase the sensitivity of tubular cells to necroptotic stimuli, the mechanism by which cisplatin induces RIP1 expression is still unknown. It is worth noting that small amounts of necrotic cells were also detected in RIP3−/− and MLKL−/− mouse kidneys 3 days after cisplatin treatment, indicating that other types of necrosis or postapoptotic necrosis occur in AKI. It has been reported that low concentrations of cisplatin (8 µM) stimulated apoptosis in PTCs after 4 days of incubation and that high concentrations of cisplatin (200–800 µM) stimulated necrosis within 4 hours.26 In our study, very-low-dose (<10 µM) cisplatin induced PTC death after prolonged treatment, but this effect was not inhibited by zVAD, QVD, the caspase-8 inhibitor Z-Ile-Glu(OMe)-Thr-Asp(OMe)-FMK (ITED) or Nec-1 (data not shown). These observations suggest that these cells might undergo other types of necrosis or caspase-independent apoptosis.

Impaired membrane integrity of necrotic cells can result in the release of damage-associated molecular patterns into the extracellular milieu and trigger inflammatory responses.27 Therefore, the severe inflammatory responses in WT mice could result predominantly from tubular cell necroptosis, although cisplatin treatment alone can induce proinflammatory cytokine expression.22 Furthermore, the inflammatory cytokines induced at day 2 to day 4 after cisplatin treatment could function in combination to stimulate increased necroptosis. Previous studies have shown that poly (ADP-ribose)-polymerase 1, Bax, p53, and cyclophilin D are involved in cisplatin-induced AKI,4,5,7,9 but the relationship between these pathways and necroptosis in AKI is unclear. Because no evidence suggests the linkage of these proteins with the necroptotic pathway, it is possible that these pathways are functionally parallel and all contribute to the pathogenesis of AKI.

In summary, our study delineates some of the mechanisms underlying cisplatin-induced nephrotoxic AKI. Cisplatin stimulates RIP1/RP3/MLKL-dependent necrotic cell death in renal tubules, which finally causes renal dysfunction. This indicates that blockade of RIP1/RIP3/MLKL signaling represents a promising strategy for clinical therapy of AKI.

Concise Methods

Mice

Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility. All experiments were approved by Laboratory Animal Management and Ethics Committee of Xiamen University, in accordance with the Chinese Guidelines on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. RIP3−/−mice and MLKL−/− mice were generated by transcription activator-like effector nucleases–mediated gene disruption in our laboratory as described previously.20 Genotypes were confirmed by tail-snip PCR amplification. Littermate WT mice were used as controls in all the animal-related experiments.

Murine Model of Cisplatin-Induced AKI

Cisplatin nephrotoxic AKI was induced in male mice (aged 8–10 weeks). Mice were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of cisplatin at 20 mg/kg. All mice received a total volume of 250 μl of normal saline with DMSO or 1.65 mg/kg of Nec-1 30 minutes before the injection of cisplatin. All groups in which Nec-1 was applied required repeated Nec-1 injections every 24 hours, with all comparison groups receiving repeated injections of 250 μl of saline with DMSO. Blood was collected for BUN and creatinine measurements. Kidneys were dissected for freshly isolation of renal proximal tubules, paraffin embedding, and electron microscopy studies. Freshly isolated renal proximal tubules were generated for Western blotting and real-time RT-PCR. Paraffin sections (4 μm) were stained with PAS or TUNEL reagent (ApopTag fluorescein in situ apoptosis detection kit), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reagents and Antibodies

Mouse anti-HA beads, mouse anti-HA, and mouse anti–β-Actin (C-15) antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Mouse anti-RIP1 antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Anti-MLKL polyclonal antibody was raised in rabbits using Escherichia coli–expressed GST-MLKL (100–200 amino acids). Anti-RIP3 and anti–phospho-RIP3 (T231/S232) antibodies were prepared as previously described in our laboratory.10,28 Anti-caspase3 and anti-caspase8 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti–glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (sc-32233) antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Nec-1 was obtained from EMB Chemicals. Z-IETD-FMK (caspase-8 inhibitor) was obtained from BD Biosciences. The pan-caspase fmk inhibitor zVAD and the pan-caspase o-phenoxy (OPH) inhibitor QVD were obtained from R&D Systems. ApopTag fluorescein in situ apoptosis detection kit (S7110) was purchased from EMD Millipore. siRNAs targeting TNF-α (Stealth siRNA MSS211991, MSS211992) and lipofectamine 3000 were purchased from Life Technology.

Primary PTC Culture

Proximal tubules were freshly isolated as described with minor modifications.5,7 Briefly, after harvesting of the kidneys, the cortices were dissected and minced on ice-cold glass before being digested for 25 minutes with 0.75 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS containing 0.75 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C. After that, DMEM/Ham F-12 (DMEM-F12) supplemented with 10% FBS was added to stop the digestion. The suspension was filtered (pore size, 100 μm), pelleted and resuspended with HBSS, followed by enrichment of proximal tubules by centrifugation on self-forming Percoll gradients, 4°C. Finally, the freshly isolated proximal tubule fragments were collected. If cultured, they were washed with DMEM-F12, then plated into collagen-coated dishes and cultured in DMEM-F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 5 µg/ml transferrin, 5 μg/ml insulin, 0.05 µM hydrocortisone, 1% nonessential amino acids, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 50 µM vitamin C at 37°C and 95% air plus 5% CO2 in a standard humidified incubator. After approximately 4 days, the cultured cells reached confluence and then were used in experiments at this point.

In Vitro Cell Death Analysis

At the end of the desired experimental period, Hoechst, PI, and annexin V stains were added. Cells or tubules were immediately viewed with a 10× objective using an Olympus IX-70 inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with filters appropriate for the observation. The percentage of dead cells was quantified from five different fields (×100 magnification) of each condition on 12-well plates. The total number of cells was measured by counterstaining with Hoechst. Percentages of annexin V–positive and PI-positive cells were counted separately.

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was obtained from freshly isolated renal proximal tubules or primary cultured renal proximal tubular epithelial cells by RNA-iso reagent (TakaRa). Purified RNA was treated with RNAse-free DNAse (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 hours at 37°C. The DNAse was then inactivated by the addition of 2.5 mM EDTA and incubation of the samples at 60°C for 10 minutes. Total RNA (2 µg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using Random Hexamer Primers (Thermo Fisher Scientfic) and M-MLV reverse transcription (BGI, Shenzheng, China). The levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, TWEAK, RIP1, RIP3, MLKL, and β-actin were determined by SYBR-Green I Real time quantitative PCR in a CFX96 real-time RT-PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). PCR amplification was carried out over 40 cycles using the following conditions: denaturation at 95°C for 20 seconds, annealing at 58°C for 20 seconds, and elongation at 72°C for 20 seconds.

Lentivirus Preparation and Infection

For lentivirus production, 293T cells were cotransfected with pBOBI expression constructs and lentivirus-packing plasmids (PMDL/REV/VSVG) by calcium phosphate precipitation. The medium was replaced after 12 hours and the virus-containing medium was harvested 36–48 hours later for addition to PTCs in the presence with 10 µg/ml polybrene. Infectious medium was changed 10 hours, later and the infected cells were used for experiments after 36–48 hours.

Plasmids and Molecular Cloning

RIP3RHIM mut (QIG449–551AAA), RIP3, MLKL, and RIP1 were amplified by PCR using specific primers,10,13,20,28 and cloned into the BamHI and XhoI sites of the modified lentiviral vector pBOBI using the Exo III-assisted ligase-free cloning method as described.29 The aspartic acid 143 (D143) in the putative Mg2+-ATP binding site substituted with an asparagine resulting in a kinase dead form: mRIP3-D143N. To construct the D143N mutation RIP3 expression plasmid, a two-round PCR method was used to amplify the DNA sequence carrying D143N mutation. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Lenti-shRNA Expression Vectors

The DNA oligos encoding shRNA sequences were designed and cloned into the expression vector pLV-1H-EF1α-puro using the single oligonucleotide RNAi technology developed by Biosettia as described elsewhere.10 All lenti-shRNA vectors were constructed following the manufacturer’s protocol. The oligo sequences were as follows: sh-RIP1 #1:AAAAgcctgagaatatcctcgttTTGGATCCAAaacgaggatattctcaggc and sh-RIP1 #2:AAAAccactagtctgactgatgaTTGGATCCAAtcatcagtcagactagtgg.

Immunoprecipitation

RIP3−/− PTCs were transfected with an expression vector encoding HA-RIP3 for 36 hours before treatment with cisplatin followed by the addition of lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitations were performed by using anti-HA beads as described.10 Western blotting of cell lysates and immunoprecipitates was performed by using anti-RIP3, anti-pRIP3, anti-RIP1, and anti-MLKL as indicated.

Western Blotting

The freshly isolated renal proximal tubules or primary cultured renal proximal tubular epithelial cells were harvested and immediately lysed with 1.2× SDS sample buffer. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (EMD Millipore) for Western blotting analysis with the appropriate antibodies. The proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (ECL; EMD Millipore).

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were independently performed in triplicate as a minimum. All data are expressed as means±SEM. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the mean values of all groups. Between-group differences were analyzed by using unpaired t tests. P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program 2015CB553800, grant N0.J1310027), the National Scientific and Technological Major Project (2013ZX10002-002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31420103910, 31330047, 91029304, 31221065, and 31090360), the Hi-Tech Research and Development Program of China (863 program 2012AA02A201, 111 Project B12001), the Science and Technology Foundation of Xiamen (no. 3502Z20130027), the Open Research Fund of State Key Laboratory of Cellular Stress Biology of Xiamen University, the Key Research Fund from the Education Department (JA12136, JK2011020) and the Health Department of Fujian Province (no. 2013-ZQN-ZD-17, wzsb201304).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arany I, Safirstein RL: Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Semin Nephrol 23: 460–464, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okada K, Ma D, Warabi E, Morito N, Akiyama K, Murata Y, Yamagata K, Bukawa H, Shoda J, Ishii T, Yanagawa T: Amelioration of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in peroxiredoxin I-deficient mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 71: 503–509, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faubel S, Ljubanovic D, Reznikov L, Somerset H, Dinarello CA, Edelstein CL: Caspase-1-deficient mice are protected against cisplatin-induced apoptosis and acute tubular necrosis. Kidney Int 66: 2202–2213, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim J, Long KE, Tang K, Padanilam BJ: Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 activation is required for cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int 82: 193–203, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linkermann A, Bräsen JH, Darding M, Jin MK, Sanz AB, Heller JO, De Zen F, Weinlich R, Ortiz A, Walczak H, Weinberg JM, Green DR, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S: Two independent pathways of regulated necrosis mediate ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 12024–12029, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings BS, Schnellmann RG: Cisplatin-induced renal cell apoptosis: Caspase 3-dependent and -independent pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302: 8–17, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei Q, Dong G, Franklin J, Dong Z: The pathological role of Bax in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int 72: 53–62, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramesh G, Reeves WB: TNFR2-mediated apoptosis and necrosis in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F610–F618, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sridevi P, Nhiayi MK, Wang JY: Genetic disruption of Abl nuclear import reduces renal apoptosis in a mouse model of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Cell Death Differ 20: 953–962, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang DW, Shao J, Lin J, Zhang N, Lu BJ, Lin SC, Dong MQ, Han J: RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science 325: 332–336, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han J, Zhong CQ, Zhang DW: Programmed necrosis: Backup to and competitor with apoptosis in the immune system. Nat Immunol 12: 1143–1149, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, Chan FK: Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137: 1112–1123, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu XN, Yang ZH, Wang XK, Zhang Y, Wan H, Song Y, Chen X, Shao J, Han J: Distinct roles of RIP1-RIP3 hetero- and RIP3-RIP3 homo-interaction in mediating necroptosis. Cell Death Differ 21: 1709–1720, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun L, Wang H, Wang Z, He S, Chen S, Liao D, Wang L, Yan J, Liu W, Lei X, Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148: 213–227, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang LF, Wang FS, Wang X: Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein MLKL causes necrotic membrane disruption upon phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol Cell 54: 133–146, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Z, Jitkaew S, Zhao J, Chiang HC, Choksi S, Liu J, Ward Y, Wu LG, Liu ZG: Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for TNF-induced necroptosis. Nat Cell Biol 16: 55–65, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin J, Li H, Yang M, Ren J, Huang Z, Han F, Huang J, Ma J, Zhang D, Zhang Z, Wu J, Huang D, Qiao M, Jin G, Wu Q, Huang Y, Du J, Han J: A role of RIP3-mediated macrophage necrosis in atherosclerosis development. Cell Reports 3: 200–210, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramachandran A, McGill MR, Xie Y, Ni HM, Ding WX, Jaeschke H: Receptor interacting protein kinase 3 is a critical early mediator of acetaminophen-induced hepatocyte necrosis in mice. Hepatology 58: 2099–2108, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM: Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol 24: 1464–1469, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu J, Huang Z, Ren J, Zhang Z, He P, Li Y, Ma J, Chen W, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Yang Z, Wu SQ, Chen L, Han J: Mlkl knockout mice demonstrate the indispensable role of Mlkl in necroptosis. Cell Res 23: 994–1006, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrier RW: Cancer therapy and renal injury. J Clin Invest 110: 743–745, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramesh G, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Reeves WB: Endotoxin and cisplatin synergistically stimulate TNF-alpha production by renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F812–F819, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, Lin Z, Zhao N, Zhou L, Liu F, Cichacz Z, Zhang L, Zhan Q, Zhao X: Receptor interactive protein kinase 3 promotes Cisplatin-triggered necrosis in apoptosis-resistant esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE 9: e100127, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Justo P, Sanz AB, Sanchez-Niño MD, Winkles JA, Lorz C, Egido J, Ortiz A: Cytokine cooperation in renal tubular cell injury: The role of TWEAK. Kidney Int 70: 1750–1758, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linkermann A, De Zen F, Weinberg J, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S: Programmed necrosis in acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3412–3419, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lieberthal W, Triaca V, Levine J: Mechanisms of death induced by cisplatin in proximal tubular epithelial cells: Apoptosis vs. necrosis. Am J Physiol 270: F700–F708, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rock KL, Kono H: The inflammatory response to cell death. Annu Rev Pathol 3: 99–126, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Zhou Z, Li L, Zhong CQ, Zheng X, Wu X, Zhang Y, Ma H, Huang D, Li W, Xia Z, Han J: Diverse sequence determinants control human and mouse receptor interacting protein 3 (RIP3) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) interaction in necroptotic signaling. J Biol Chem 288: 16247–16261, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Evans RM: Ligation independent cloning irrespective of restriction site compatibility. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 4165–4166, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]