Abstract

Patient-derived tumor xenograft is the transfer of primary human tumors directly into an immunodeficient mouse. Patient-derived tumor xenograft plays an important role in the development and evaluation of new chemotherapeutic agents. We succeeded in generating a patient-derived tumor xenograft of a biliary tumor obtained by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration from a patient who had an inoperable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. This patient-derived tumor xenograft will be a promising tool for individualized cancer therapy and can be used in developing new chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of biliary cancer in the future.

Keywords: Cholangiocarcinoma, Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration, Individualized medicine, Xenograft

INTRODUCTION

Patient-derived tumor xenograft (PDTX) is the transfer of human primary tumors directly into an immunodeficient mouse. Patient-derived tumor xenograft models have been applied to preclinical drug testing and biomarker identification in a number of cancers1,2 because these models reflect the biological characteristics of human tumors more accurately than those of tumor cell lines.3

We successfully engrafted a human biliary tumor to an athymic nude mouse. To our knowledge, this is not only the first report of a successfully xenografted specimen from an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), but is also the first report of a xenografted human biliary tumor.2

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old man who had previously been healthy was transferred to our clinic with a 2-week history of jaundice. Laboratory tests and a contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography scan had been performed at another hospital. These tests demonstrated hyperbilirubinemia and an enhancing mass at the distal common bile duct, with diffuse intra- and extra-hepatic bile duct dilation (Fig. 1A and B). Before admission, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage for bile duct decompression was performed at another hospital. The patient was transferred to our clinic for further evaluation and treatment.

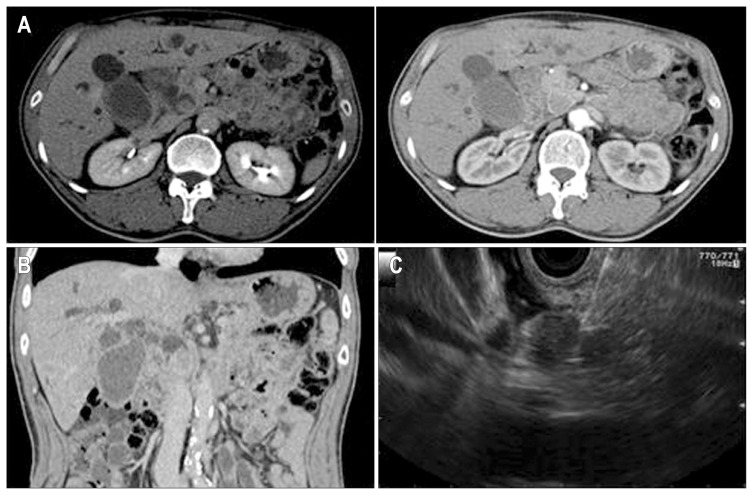

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) imaging. (A, B) Contrast-enhanced CT showed an enhancing mass lesion at the distal common bile duct and diffuse intra- and extrahepatic bile duct dilation. (C) EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration was performed to obtain a pathologic and xenograft specimens for the intraductal mass.

EUS examination revealed a round mass in the intrapancreatic bile duct, with hypoechoic areas and heterogeneous echogenicity. The mass measured 21×16 mm in maximal cross-sectional diameter. The endosonographic borders were well defined. After obtaining written informed consent for the procedures and potential risks, we performed a diagnostic needle aspiration of the mass. Color Doppler imaging was obtained prior to the needle puncture to confirm a lack of significant vascular structures within the needle path. Five passes were made with a 22-gauge needle (EchoTip; Cook Medical Inc., Winston-Salem, NC, USA) by a transduodenal approach (Fig. 1C). The specimens acquired from the first three passes were prepared for cytopathologic diagnosis, and those from the last two passes were used for the xenograft. Written informed consent for xenograft research was also obtained from the patient, and we received permission from the Institutional Review Board (number: KNUMC_14-1010).

The acquired FNA specimen was cut into a 2-mm cube and mixed with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA). The mixture of tumor tissue-Matrigel was implanted subcutaneously into the flank of a 6-week-old female BALB/c-nu mouse (SLC Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan) that was anesthetized with isoflurane. All of the animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the institutional guidelines for animal research. After 6.5 months, a 1.3-cm3 tumor was removed and analyzed (Fig. 2). Histologic and immunohistochemical staining of the xenografted tumor demonstrated identical pathologic patterns to those of the human tumor (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

After the implantation of human tumor tissue into an athymic mouse, a visible engrafted mass was identified on the back, measuring 1 cm in diameter. The enucleated mass measured 10×10 mm in maximal cross-sectional diameter.

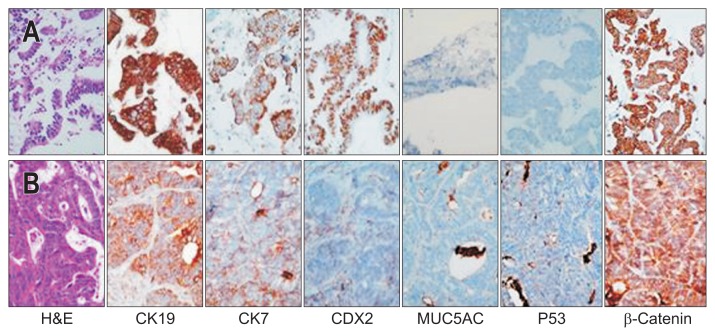

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemistry findings in the human endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration specimen (A) and in the xenografted mass (B). The immunohistochemical staining showed a similar pattern in the human specimen and the xenografted material.

DISCUSSION

PDTX models have been established and are increasingly used for preclinical studies of chemotherapeutic responses. However, PDTX models for cholangiocarcinoma are relatively few in number and are limited in their degree of genetic characterization and validation.

Three models have been used to evaluate the preclinical response to new anticancer drugs: genetically engineered models, xenografts derived from human cell lines, and patient-derived xenografts.3 PDTX models are superior in reproducing the characteristics and clinical course of cancer. Xenografts that are derived from human cancer cell lines are more homogeneous and undifferentiated because of selection pressures occurring during long-term in vitro culture.4

Some experimental trials for the treatment of bile duct cancers have been performed. In 1992, experimental chemotherapy for the treatment of xenografted human bile duct and gall bladder cancer cell lines was carried out in nude mice.5 In addition, in 2003, one study reported the successful establishment and characterization of two xenograft models of human biliary tract cancer, using fresh cell lines that were created from surgical specimens of bile duct adenocarcinoma.6 However, these results are from xenografts that were derived from human tumor cell lines and do not sufficiently represent clinical cancer characteristics, especially with regard to metastasis and drug sensitivity.2

This case report describes a successful patient-derived xenograft from bile duct cancer; it seems to be the first such report in bile duct cancer and is the first use of an EUS-FNA specimen to create the xenograft. In this case, the bile duct cancer featured mass formation and papillary growth, and the EUS-FNA specimen contained a large number of cancer cells.

Although most tumor tissues that are used in patient-derived xenografts have been obtained by surgical excision,7 it is difficult to obtain biliary cancer tissues by surgical excision for use in xenografting. Because malignant biliary tumors are usually advanced and inoperable at diagnosis, chemotherapy is usually the main treatment option.8 Furthermore, bile duct cancer is not only diverse in terms of anatomical location but is also diverse at the genetic level. Many studies have performed molecular and cellular analyses to investigate gene and protein expression in bile duct cancer.9,10

Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas usually feature sclerosing or periductal infiltration and contain a large amount of fibrotic tissue. However, in this case, the cholangiocarcinoma was characterized by mass formation, which yielded more cancer cells in the aspirated specimen than the sclerosing or periductal infiltrating type. Unfortunately, it took a long time for the xenografted mass to reach a visible size. This result might be due to both the paucity of the inoculated tumor cells compared to the surgical specimen and characteristics of the slow-growing tumor itself. Further xenograft studies using more bile duct cancers are needed to improve technical skills and increase the yield of cancer cells.

As a first report of successful PDTX using EUS-FNA specimen, we expect that this case may contribute to the development of a tailored therapy for bile duct cancer in the future. However, further studies are required to shorten the growth period to obtain a sufficient volume of xenograft before applying clinical management.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: A111345).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott CL, Becker MA, Haluska P, Samimi G. Patient-derived xenograft models to improve targeted therapy in epithelial ovarian cancer treatment. Front Oncol. 2013;3:295. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin K, Teng L, Shen Y, He K, Xu Z, Li G. Patient-derived human tumour tissue xenografts in immunodeficient mice: a systematic review. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12:473–480. doi: 10.1007/s12094-010-0540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herter-Sprie GS, Kung AL, Wong KK. New cast for a new era: preclinical cancer drug development revisited. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3639–3645. doi: 10.1172/JCI68340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausser HJ, Brenner RE. Phenotypic instability of Saos-2 cells in long-term culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsubono M, Nio Y, Tseng CC, et al. Experimental chemotherapy for xenograft cell lines of human bile duct and gall bladder cancers in nude mice. J Surg Oncol. 1992;51:274–280. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930510415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emura F, Kamma H, Ghosh M, et al. Establishment and characterization of novel xenograft models of human biliary tract carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1293–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siolas D, Hannon GJ. Patient-derived tumor xenografts: transforming clinical samples into mouse models. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5315–5319. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanna C, Jaboin JJ, Drakos E, Tsokos M, Thiele CJ. Biologically relevant orthotopic neuroblastoma xenograft models: primary adrenal tumor growth and spontaneous distant metastasis. In Vivo. 2002;16:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tonini G, Virzì V, Fratto ME, Vincenzi B, Santini D. Targeted therapy in biliary tract cancer: 2009 update. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1675–1684. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amano R, Yamada N, Doi Y, et al. Significance of keratinocyte growth factor receptor in the proliferation of biliary tract cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4115–4121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]