Abstract

Background

Small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (sdLDL-C) concentration was useful in the assessment of the presence of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and its severity. We examined whether SdLDL-C is more closely associated with carotid artery intima-media thickness (CA-IMT), a surrogate measure of atherosclerosis, than LDL-C and traditional CVD risk factors in Chinese healthy subjects.

Methods

We measured CA-IMT, blood pressure (BP), sdLDL-C, glucose metabolism and lipid in 183 native Chinese healthy subjects. CA-IMT was assessed by ultrasonography, and sdLDL-C concentrations were measured by a homogenous assay. Pearson's correlation coefficient analyses and Multiple regression analyses were used to examine the relationships between CA-IMT values and other clinical variables.

Results

The sdLDL-C level was significantly higher in males than in females (p <0.05) and there was an age effect on sdLDL-C (p <0.05). When the effects of age, gender and other traditional CVD risk factors were adjusted using multiple regression analysis. CA-IMT remained significantly associated with sdLDL-C(β = 0.437, p <0.001).

Conclusions

There are gender and age differences in sdLDL-C levels among a healthy Chinese population. Moreover, we found adjusted traditional CVD risk factors such as higher age, male sex, and other traditional CVD risk factors, the association between CA-IMT and SdLDL-C remained significant. sdLDL-C is may be a useful predictor in the assessment of CA-IMT in Chinese population.

Keywords: Small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Carotid artery intima-media thickness, Chinese subjects

Background

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) consists of a continuum of particles varying in size, density, electrical charge, and chemical (lipid and apo-protein) composition. LDL was identified in the density range 1.019–1.060 g/ml, namely large buoyant LDL (lbLDL), and range 1.034–1.044 g/ml, namely small dense LDL (sdLDL) [1, 2]. Compared with lbLDL, small dense LDL cholesterol (sdLDL-C) is thought to be more atherogenic [3]. Indeed, higher levels of sdLDL particles are considered to be more atherogenic compared with lbLDL cholesterol (lbLDL-C) particles; therefore, sdLDL-C is considered to be an important and independent predictor of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [4–8]. Thus, the selective measurement of sdLDL-C concentrations is useful for evaluating the actual atherogenic risk of individuals. The sdLDL is traditionally measured by ultracentrifugation [9] or gradient gel electrophoresis (GGE) [10] to evaluate the density or LDL particle size, respectively. However, both methods are laborious and require special equipment and a long running time. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) imaging is capable of simultaneously determining the size and number of LDL particles [11]. However, the instrumentation required for NMR is too expensive for general clinical laboratories to acquire feasibly. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) enables the determination of lipid concentrations in various lipoprotein subfractions [12]. However, HPLC is also laborious, time-consuming, and expensive for routine clinical use. Hirano et al. [13] have developed a method that uses heparin sodium salt precipitation followed by centrifugation for measuring sdLDL-C, and it still required offline sample pretreatment that hindered its smooth integration into general clinical use. Recently, a new fully automated homogenous assay for measuring sdLDL-C was being used, and sdLDL-C values showed excellent agreement with the sdLDL isolation by sequential ultracentrifugation [14]. This precise and rapid method allows for the routine of large number of samples.

Carotid artery intima-media thickness (CA-IMT) has been utilized as one of the surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease in different populations [15, 16]. CA-IMT increases in high-risk populations such as elderly people [17], those with hypertension [18], diabetes mellitus [19], and chronic kidney disease [20, 21]. Although several studies have reported an association between CA-IMT and LDL particle size distribution in the Japanese and U.S. populations [22–25], it has not been studied in the Chinese population, especially the healthy Chinese population. Furthermore, the measurement of sdLDL-C concentration was useful in the assessment of the presence of CVD [13, 26] and its severity [24]. In addition, a recent publication by Arai et al. [27] demonstrated the utility of the sdLDL-C concentration as a predictive marker for CVD incidence. Since the etiology of CVD is complex, involving environmental and genetic factors that might change from one population to the other, it is important to assess this association in Chinese populations. sdLDL-C is may b a useful predictor in the assessment of CA-IMT in Chinese subjects.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate whether the quantitative measurement of SdLDL-C gives better information in CVD risk assessment than standard LDL-C and other lipid variables using CA-IMT as a surrogate measure of atherosclerosis.

Results

sdLDL-C and various parameters in the study subjects

One hundred eighty-three subjects were classified into males group and females group. The age of the subjects ranged from 20 to 78 years old, and the mean age was 45.8 ± 14.6y. Each subject had a normal chemistry and physical profile, and the subject characteristics are summarized in (Table 1). We found that the males group had significantly higher BMI, Systolic BP, TC, sdLDL-C levels than females group (p <0.05), and had significantly lower HDL-C level than females group (p <0.05).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Variable | Male | Female | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 95 | 88 | – |

| Age (year) | 47.31 ± 14.58 | 44.20 ± 14.62 | 0.153 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.65 ± 3.61 | 22.64 ± 3.32 | 0.042 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 117.37 ± 12.23 | 113.15 ± 10.80 | 0.015 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 83.23 ± 6.34 | 81.81 ± 5.26 | 0.088 |

| Family CVD events | 43/95 | 39/88 | 0.898 |

| FBG (mg/dl) | 88.41 ± 7.89 | 88.87 ± 8.12 | 0.701 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.34 ± 0.93 | 5.18 ± 0.87 | 0.232 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 88.83 ± 28.91 | 82.86 ± 27.89 | 0.157 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 167.94 ± 18.66 | 161.38 ± 18.55 | 0.018 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 48.43 ± 9.61 | 54.81 ± 9.64 | <0.001 |

| Non- HDL-C (mg/dl) | 112.96 ± 15.16 | 113.13 ± 15.12 | 0.939 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 96.71 ± 12.14 | 96.72 ± 12.25 | 0.994 |

| LbLDL-C (mg/dl) | 83.23 ± 11.93 | 82.92 ± 11.69 | 0.858 |

| SdLDL-C (mg/dl) | 14.1 ± 3.9 | 13.2 ± 3.1 | 0.041 |

| CA-IMT (mm) | 0.54 ± 0.13 | 0.52 ± 0.14 | 0.154 |

Continuous and categorical variables data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviations and real number of subjects, respectively. Means were compared between male and female groups by Student’s t-test. The χ-square test was employed to compare Family CVD events distribution

Abbreviation: BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure, FBG fasting blood glucose, HbAlc hemoglobin A1c, TG triglyceride, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, lbLDL-C large buoyant LDL-C, SdLDL-C small dense LDL-C, CA-IMT carotid artery intima-media thickness LbLDL-C (mg/dl) = LDL-C (mg/dl) − SdLDL-C (mg/dl)

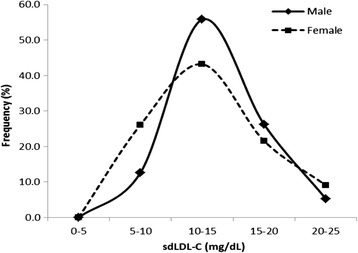

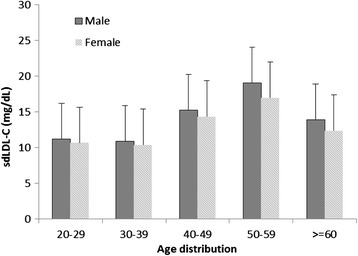

sdLDL-C in the healthy subjects

We compared the frequency distribution of sdLDL-C among females and males first (Fig. 1) and then separated the healthy female and male population into five age groups (Fig. 2) in order to determine whether there was an age or a gender difference. We found that there was an age effect on sdLDL-C in both males and females. The sdLDL-C level was significantly higher in males above 50 years old than those below 50 years old (16.4 ± 4.1 vs 13.3 ± 3.2 mg/dl, p <0.01). Females above 40 years old had a higher sdLDL-C level than those below 40 years old (14.4 ± 3.9 vs 12.1 ± 3.0 mg/dl, p <0.01). The percentiles of sdLDL-C value are summarized in (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

The frequency distribution of small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (sdLDL-C) of healthy males and females with normolipidemia

Fig. 2.

Normal small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (sdLDL-C) concentrations in various age groups and in males and female

Table 2.

The percentiles of sdLDL-C value

| Variable | sdLDL-C (mg/dl) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P25 | P50 | P75 | P95 | |

| All subjects | 10.3 | 12.5 | 15.7 | 21.0 |

| Males | 10.6 | 12.9 | 16.1 | 21.6 |

| Females | 9.3 | 12.3 | 15.6 | 20.6 |

Abbreviations are the same as those for Table 1

Correlation between sdLDL-C and CA-IMT

The results of the Pearson's correlation coefficient analyses revealed that CA-IMT was positively correlated with age (r = 0.770, p <0.001), systolic BP (r = 0.398, p <0.001), diastolic BP (r = 0.343, p <0.001), fasting plasma glucose (r = 0.261, p <0.001), HbA1c (r = 0.192, p = 0.009), total cholesterol (r = 0.202, p =0.006), triglycerides (r = 0.226, p = 0.002), LDL cholesterol (r = 0.340, p <0.001), non-HDL cholesterol (r = 0.149, p = 0.044), large buoyant LDL cholesterol (r = 0.182, p = 0.014), and sdLDL-C (r = 0.436, p <0.001), but had no significant association with other clinical variables (Table 3). The results of the multiple regression analysis: First: sdLDL-C as an independent variable adjusted for age and sex revealed that dependent CA-IMT determinants remained significantly associated with sdLDL-C; Second: adjustment for Family CVD history, smoking, systolic BP, diastolic BP, FBG, HbA1c, TC, HDL-C, TC, LDL-C, non-HDL cholesterol, large buoyant LDL cholesterol, and sdLDL-C revealed that dependent CA-IMT determinants remained significantly associated with sdLDL-C (Table 4).

Table 3.

Correlation between CA-IMT values and sdLDL-C values and other variables

| Variable | r | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.770 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.106 | 0.153 |

| Systolic BP | 0.398 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP | 0.343 | <0.001 |

| FBG | 0.261 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c | 0.192 | 0.009 |

| TC | 0.202 | 0.006 |

| HDL-C | −0.065 | 0.385 |

| TG | 0.226 | 0.002 |

| LDL-C | 0.340 | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 0.149 | 0.044 |

| LbLDL-C | 0.182 | 0.014 |

| SdLDL-C | 0.436 | <0.001 |

Pearson's correlation coefficient analyses were used to explore the relationships

Abbreviations are the same as those for Table 1

Table 4.

Multivariate associations of CA-IMT with SdLDL-C and other parameters adjusted by age and sex

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P | β | P | |

| Age | 0.562 | <0.001 | 0.422 | <0.001 |

| Sex (Male vs. Female) | −0.116 | 0.269 | −0.132 | 0.067 |

| Family CVD history (Yes vs No) | 0.313 | <0.001 | ||

| BMI | 0.105 | 0.155 | ||

| Smoking (Smokers vs non-smokers) | 0.156 | 0.021 | ||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 0.298 | <0.001 | ||

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 0.287 | <0.001 | ||

| FBG (mg/dl) | 0.098 | 0.252 | ||

| Log TC (mg/dl) | 0.052 | 0.478 | ||

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 0.061 | 0.450 | ||

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 0.123 | 0.084 | ||

| SdLDL-C (mg/dl) | 0.406 | <0.001 | 0.437 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations are the same as those for Table 1

Discussion

In this study, we observed that there are gender and age differences in sdLDL-C levels among our tested population, consistenting with the data obtained in the Western populations [26, 28]. Although we have not separated menopausal and premenopausal women, women above 40 years old had a higher sdLDL-C concentration than those below 40 years old. Several studies have consistently shown more favorable lipoprotein profiles among premenopausal women than among men due to estrogen-related protective mechanisms [29, 30]. It is well known that CVD risk markedly increases with aging in men and menopausal women, and alterations in LDL clearly contribute to this increased risk [31].

Moreover, we compared the associations of CA-IMT with SdLDL-C, LDL-C and other various risk factors for CVD in 183 healthy Chinese population. In univariate analysis, CA-IMT was most closely associated with SdLDL-C among the variables tested. This was also true when the effects of age, gender and other traditional CVD risk factors were adjusted using multiple regression analysis. These results suggest that SdLDL-C is a quantitative risk marker of CVD that is more closely associated with CA-IMT than the standard lipid parameters in healthy Chinese population.

Previous studies [22, 24, 25] showed that an association between CA-IMT and sdLDL-C concentrations measured by other methods. Using GGE, Skoglund-Andersson et al. [22] found that plasma concentration of the predominant sdLDL-C subfraction correlated strongly with common CA-IMT in healthy 50-year-old men. Shoji et al. [24] reported that CA-IMT was strongly correlated with sdLDL-C in subjects with dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease, as well as in smokers by simple precipitation methods. Using NMR, Maeda et al. [25] showed that, compared with TC and LDL-C, abnormalities in HDL-C and sdLDL-C were more strongly and consistently associated with common CA-IMT in patient with moderate chronic kidney disease. In the present study we measured CA-IMT as one of the surrogate markers of atherosclerosis, and found that CA-IMT was more closely associated with SdLDL-C than other lipid parameters tested in healthy Chinese population.

The key finding of this study was that SdLDL-C was a better lipid variable than other standard parameters in assessing the risk of CVD using CA-IMT in healthy population. There are several explanations for this finding. First, SdLDL-C was associated with CA-IMT due simply to its increased level in other traditional CVD risk factors. In fact, we found adjusted traditional CVD risk factors such as higher age, male sex, smoking and Family CVD history, the association between CA-IMT and SdLDL-C remained significant. Therefore, although SdLDL-C is interrelated with other coronary risk factors, such relations do not fully explain the superior association of SdLDL-C with CA-IMT. Second, sdLDL is higher susceptibility to oxidation, and oxidized LDL induces smooth muscle cell proliferation [32], therefore, sdLDL are more atherogenic [33]. sdLDL may initiate the development of carotid atherosclerosis, and we speculate that sdLDL-C concentrations may have a close relationship with CA-IMT.

The present study has some limitations. First, the cohort was relatively small. Second, only the healthy subjects enrolled in the present study. Subjects with coronary risk factors or CVD are required. Finally, being a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to determine a cause and effect relationship between sdLDL-C concentrations and CA-IMT. Further studies are needed to clarify whether CA-IMT is with sdLDL-C concentrations, as measured by homogenous assay, in subjects with coronary risk factors or CVD.

Conclusion

We observed that there are gender and age differences in sdLDL-C levels among a healthy Chinese population. Moreover, we found adjusted traditional CVD risk factors such as higher age, male sex, smoking and Family CVD history, the association between CA-IMT and SdLDL-C remained significant. sdLDL-C is may be a useful predictor in the assessment of CA-IMT in Chinese population.

Materials and methods

Study participants

One hundred eighty-three healthy subjects were randomly collected from consecutive subjects visiting The First People's Hospital of Wujiang, for an annual health checkup from April 2014 to April 2015. The including criteria were: 1) All subjects were native Chinese, and required to have lived in Suzhou since birth. 2) The age should be more than 20 years old. 3) We excluded all subjects with a history of CVD, thromboembolic disease or congestive heart failure; peripheral arterial disease; malignancy; infectious disease; liver or renal disease; overt endocrine disease. In addition, subjects with hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, as defined by the diagnostic criteria [31, 34, 35] were not included. None of the healthy subjects were currently taking any medications that could influence glycemic and lipid.

All subjects were divided into female group, male group and 5 age groups (20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50-59, and ≥60 years old). Comparisons of mean values of CA-IMT, BP, sdLDL-C, glucose metabolism and lipid between both males and females, and sdLDL-C concentrations in various age groups and in males and females by Student’s t-test. The height and weight of subjects were measured and the body mass index (BMI, weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was calculated. BP was measured in the morning (after a 12 h fast) by the same investigator with a sphygmomanometer on the right arm of the subject after a 10-min rest in the supine position. We performed physical examinations and CA-IMT examinations in the morning (after a 12 h fast) and obtained blood samples from the antecubital vein for serum and plasma analyses at the same time. This study was approved by the local ethics committee and was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each subject provided informed consent.

Carotid ultrasonography

A trained technicians who was blinded to the clinical characteristics of subject groups evaluated the wall thickness of the carotid arteries in all participants using high-resolution B-mode ultrasound (Philips iU22 ultrasound System) equipped with a L9-3 (7.5 MHz) linear array transducer (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) [36]. After the subject had rested for at least 10 min in the supine position with the neck in slight hyperextension, we evaluated the optimal visualization of the common carotid arteries, carotid bulb, and extracranial internal and external carotid arteries bilaterally. CA-IMT was assessed as the greatest CA-IMT at any location in the far walls of these carotid arteries on both sides. The max CA-IMT was defined as the greater of the 2 unilateral CA-IMT values [37].

Laboratory measurements

Fasting blood glucose (FBG), Total cholesterol (TC), Triglyceride (TG), High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) were measured by standard laboratory procedures. An automatic biochemistry analyzer (Hitachi-7600; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was used for all above tests, using standard kits. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level was determined by HPLC, using automatic analyzer (ADAMS A1c HA-8181, Arkray). The value of HbA1c (%) was estimated as a National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) equivalent value (%) derived from the Japanese Diabetes Society (JDS) value and calculated by the formula HbA1c (%) = HbA1c (JDS) (%) +0.4 % [38]. The sdLDL-C was measured using a newly developed homogenous assay in an automatic analyzer (Hitachi-7600; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), and commercial kit (sdLDL-C, SEIKEN; Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) was used for determination as we previously reported [39].

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD, and comparisons by Student’s t-test. The χ-square test was employed to compare categorical data. The difference in frequency data was determined by Chi-squared test. Pearson's correlation coefficient analyses were used to explore the relationships between CA-IMT values and sdLDL-C values and other clinical variables. Multiple regression analysis was performed using CA-IMT values, sdLDL-C values, and those of the other clinical variables. All the probability values were 2-tailed and differences with P <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All tests were performed by SPSS program version 20.0.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Jiangsu Provincial and Wujiang District Health Bureau for Invigorating Health Engineering projects (XK200723 and WWK201417).

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- CA-IMT

carotid artery intima-media thickness

- CVD

cardiovascular diseases

- GGE

gradient gel electrophoresis

- HbAlc

hemoglobin A1c

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

HDL cholesterol

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- lbLDL

large buoyant LDL

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LDL-C

LDL cholesterol

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- sdLDL

small dense LDL

- sdLDL-C

small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

Footnotes

Hao Shen and Li Xu contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LJF, MCF, HTB and YHL carried out the centrifugation, analysed samples, performed data and statistical analyses and prepared the figures. ZTH, GYC and LZY helped with acquisition of data. XL, SH and SGR designed the study and protocols, oversaw the laboratory work and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Hao Shen, Phone: +86-13912703667, Email: shenhaojyk@126.com.

Li Xu, Email: 43831977@qq.com.

Jingfen Lu, Email: petiteberyl@163.com.

Tianbo Hao, Email: haotianbojiayou@163.com.

Chunfang Ma, Email: njmacf@163.com.

Honglin Yang, Email: 285170388@qq.com.

Zhaoyang Lu, Email: 2206860@qq.com.

Yongchun Gu, Email: 307332805@qq.com.

Tonghua Zhu, Email: wjthzhu@sina.com.

Guorong Shen, Email: 530045012@qq.com.

References

- 1.Krauss RM. Low-density lipoprotein subclasses and risk of coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1991;2:248–52. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199108000-00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krauss RM, Blanche PJ. Detection and quantitation of LDL subfractions. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1992;3:373–83. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199212000-00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffin BA. Lipoprotein atherogenicity: an overview of current mechanisms. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:163–9. doi: 10.1079/PNS19990022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stalenhoef AF, de Graaf J. Association of fasting and nonfasting serum triglycerides with cardiovascular disease and the role of remnant-like lipoproteins and small dense LDL. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(4):355–61. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328304b63c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin MA, Breslow JL, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Willett WC, Krauss RM. Low-density lipoprotein subclass patterns and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1988;260:1917–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.1988.03410130125037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikhailidis DP, Elisaf M, Rizzo M, Berneis K, Griffin B, Zambon A, et al. “European panel on low density lipoprotein (LDL) subclasses”: a statement on the pathophysiology, atherogenicity and clinical significance of LDL subclasses. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2011;9:533–71. doi: 10.2174/157016111796642661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blake GJ, Otvos JD, Rifai N, Ridker PM. Low-density lipoprotein particle concentration and size as determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as predictors of cardiovascular disease in women. Circulation. 2002;106:1930–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000033222.75187.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Harchaoui K, van der Steeg WA, Stroes ES, Kuivenhoven JA, Otvos JD, Wareham NJ, et al. Value of low-density lipoprotein particle number and size as predictors of coronary artery disease in apparently healthy men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swinkels DW, Hak-Lemmers HL, Demacker PN. Single spin density gradient ultracentrifugation method for the detection and isolation of light and heavy low density lipoprotein subfractions. J Lipid Res. 1987;28:1233–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nichols AV, Krauss RM, Musliner TA. Nondenaturing polyacrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1986;128:417–31. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)28084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otvos JD, Jeyarajah EJ, Bennett DW, Krauss RM. Development of a proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic method for determining plasma lipoprotein concentrations and subspecies distributions from a single, rapid measurement. Clin Chem. 1992;38:1632–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usui S, Nakamura M, Jitsukata K, Nara M, Hosaki S, Okazaki M. Assessment of between-instrument variations in a HPLC method for serum lipoproteins and its traceability to reference methods for total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol. Clin Chem. 2000;46:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano T, Ito Y, Koba S, Toyoda M, Ikejiri A, Saegusa H, et al. Clinical significance of small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels determined by the simple precipitation method. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:558–63. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000117179.92263.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albers JJ, Kennedy H, Marcovina SM. Evaluation of a new homogenous method for detection of small dense LDL cholesterol: Comparison with the LDL cholesterol profile obtained by density gradient ultracentrifugation. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:556–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Leary D, Polak J. Intima-media thickness: a tool for atherosclerosis imaging and event prediction. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:L18–L21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(02)02957-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishizawa Y, Shoji T, Maekawa K, Nagasue K, Okuno S, Kim M, et al. Intima-media thickness of carotid artery predicts cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:S76–9. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Savage PJ, Borhani NO, Kittner SJ, et al. Thickening of the carotid wall. A marker for atherosclerosis in the elderly? Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Stroke. 1996;27:224–31. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.27.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakka TA, Salonen R, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Blood pressure and the progression of carotid atherosclerosis in middle-aged men. Hypertension. 1999;34:51–6. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.34.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kogawa K, Nishizawa Y, Hosoi M, Kawagishi T, Maekawa K, Shoji T, et al. Effect of polymorphism of apolipoprotein E and angiotensin-converting enzyme genes on arterial wall thickness. Diabetes. 1997;46:682–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawagishi T, Nishizawa Y, Konishi T, Kawasaki K, Emoto M, Shoji T, et al. High-resolution B-mode ultrasonography in evaluation of atherosclerosis in uremia. Kidney Int. 1995;48:820–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoji T, Emoto M, Tabata T, Kimoto E, Shinohara K, Maekawa K. Advanced atherosclerosis in predialysis patients with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2187–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoglund-Andersson C, Tang R, Bond MG, de Faire U, Hamsten A, Karpe F. LDL particle size distribution is associated with carotid intima-media thickness in healthy 50-year-old men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2422–30. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.19.10.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamprea-Montealegre JA, Astor BC, McClelland RL, de Boer IH, Burke GL, Sibley CT, et al. CKD, plasma lipids, and common carotid intima-media thickness: results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1777–85. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02090212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shoji T, Hatsuda S, Tsuchikura S, Shinohara K, Kimoto E, Koyama H. Small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration and carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2008;202:582–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maeda S, Nakanishi S, Yoneda M, Awaya T, Yamane K, Hirano T. Associations between small dense LDL, HDL subfractions (HDL2, HDL3) and risk of atherosclerosis in Japanese-Americans. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2012;19:444–52. doi: 10.5551/jat.11445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ai M, Otokozawa S, Asztalos BF, Ito Y, Nakajima K, White CC. Small dense LDL cholesterol and coronary heart disease: results from the Framingham Offspring Study. Clin Chem. 2010;56(6):967–76. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.137489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arai H, Kokubo Y, Watanabe M, Sawamura T, Ito Y, Minagawa A. Small dense low-density lipoproteins cholesterol can predict incident cardiovascular disease in an urban Japanese cohort: the Suita study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2013;20:195–203. doi: 10.5551/jat.14936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vekic J, Zeljkovic A, Jelic-Ivanovic Z, Spasojevic-Kalimanovska V, Bogavac-Stanojevic N, Memon L, et al. Small, dense LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B: relationship with serum lipids and LDL size. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campos H, McNamara JR, Wilson PW, Ordovas JM, Schaefer EJ. Differences in low density lipoprotein subfractions and apolipoproteins in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:30–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-1-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CC, Huang T. Association of serum lipid profiles with depressive and anxiety disorders in menopausal women. Chang Gung Med J. 2006;29:325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heery JM, Kozak M, Stafforini DM, Jones DA, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, et al. Oxidatively modified LDL contains phospholipids with platelet-activating factor-like activity and stimulates the growth of smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2322–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI118288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chait A, Brazg RL, Tribble DL, Krauss RM. Susceptibility of small, dense, low-density lipoproteins to oxidative modification in subjects with the atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype, pattern B. Am J Med. 1993;94:35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90144-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Diabetes Association Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes-2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S4–10. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sumino H, Ichikawa S, Kasama S, Kumakura H, Takayama Y, Sakamaki T. Effect of transdermal hormone replacement therapy on carotid artery wall thickness and levels of vascular inflammatory markers in postmenopausal women. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:579–84. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoki T, Yagi H, Sumino H, Tsunekawa K, Araki O, Kimura T, et al. Relationship between carotid artery intima-media thickness and small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations measured by homogenous assay in Japanese subjects. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;442:110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seino Y, Nanjo K, Tajima N, Kadowaki T, Kashiwagi A, Araki E. The Committee of Japan Diabetes Society on the diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus: Report of the Committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Invest. 2010;1:212–28. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen H, Zhou J, Shen G, Yang H, Lu Z, Wang H. Correlation between serum levels of small, dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and carotid stenosis in cerebral infarction patients >65 years of age. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]