Abstract

Common gynecologic conditions and surgeries may vary significantly by race or ethnicity. Uterine fibroids are more prevalent in black women and black women may have larger, more numerous fibroids that cause worse symptoms and greater myomectomy complications. Some, but not all, studies have found a higher prevalence of endometriosis among Asian women. Race and ethnicity are also associated with hysterectomy rate, route, and complications. Overall, the current literature has significant deficits in identifying racial and ethnic disparities in fibroids, endometriosis, and hysterectomy. Further research is needed to better define racial and ethnic differences in these conditions, and examine the complex mechanisms that may result in associated health disparities.

Keywords: disparities in benign gynecology

Introduction

Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of common benign gynecologic conditions and the use of surgical treatments have been reported. These differences may result in significant health disparities among some racial and ethnic groups. Although there are many areas of gynecology to consider, we will focus on uterine fibroids and endometriosis, two of the most common conditions encountered in clinical practice, and hysterectomy, the most frequently performed major gynecologic surgery. Our review will highlight racial and ethnic differences in the burden of disease associated with fibroids and endometriosis, and in the rate, route, and outcomes of hysterectomy. We will emphasize the need for further research to better understand the reasons for these racial and ethnic differences, with the goal of decreasing significant health disparities.

The cause of racial and ethnic differences in these gynecologic conditions and surgeries are not fully understood. A complex set of genetic, physiologic, sociodemographic, cultural, and economic factors likely contribute to racial and ethnic disparities, as has been described in other fields of medicine.1, 2 Differences in patient preferences by race and ethnicity may also influence treatment decisions resulting in differential rates of surgery. There are also challenges in the measurement and categorization of race and ethnicity that hinder a complete understanding of racial and ethnic variation for gynecologic conditions. (reference AJOG editorial in press “Health Disparities: definitions and measurements”). We will examine some of the potential causes of gynecologic health disparities and describe limitations in the literature that create significant knowledge gaps.

Uterine Leiomyomas (Fibroids)

Several studies have found a higher prevalence of fibroids among black women compared with white women.3–5 However, these studies evaluate women undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy, which may not accurately represent the true distribution of fibroids in the general population; racial and ethnic variation in disease severity, access to non-surgical treatment, or treatment preferences may result in a higher prevalence of surgery among black women. One study attempted to overcome this limitation by screening randomly selected women age 35–49 years for fibroids with pelvic ultrasound. After adjusting for body mass index (BMI) and parity, black women were nearly three times as likely to have fibroids compared with white women (O.R. 2.7, 95%CI 2.3–3.2).6 Two other studies include women who underwent surgical management of fibroids and those who did not. Among 95,061 premenopausal participants in the Nurses Health Study II, black women had three times the odds of receiving a diagnosis of fibroids by pelvic exam, ultrasound, or hysterectomy compared with white women (O.R. 3.3, 95%CI 3.0, 4.3).7 Similarly, in adjusted analysis from a case-control study of patients who received either surgical or medical management of fibroids, black women had nine times the odds of clinically apparent fibroids (O.R. 9.4, 95%CI 5.7, 15.7).8

Although studies of patients undergoing surgery have significant limitations for estimating fibroid prevalence, they are critical for exploring disparities in the surgical burden among women with fibroids. In an uncontrolled nationwide analysis, the rate of hysterectomy for fibroids was 37.6 per 10,000 black women compared with 16.4 per 100,000 white women.9 In a prospective cohort study of approximately 80,000 women in California, black women had a significantly higher rate of undergoing surgery for fibroids compared with non-Latina white women in a model that controlled for age and family history of fibroids (RR 2.28, 95%CI 1.81–2.87).5 Several smaller studies have confirmed this higher prevalence of fibroids among black women undergoing hysterectomy and/or myomectomy.3, 4

In addition to a higher rate of fibroids, several studies have found that black women present at a younger age with larger, more numerous, and more rapidly growing fibroids compared with white women. Huyck et al. reported a mean age for fibroid diagnosis of 31 years among black women and 37 years among white women (p<.001).10 Three other studies have confirmed this finding, with black women receiving a diagnosis of fibroids three or more years before white women.3, 7, 11 In a random sample of women, ultrasound detected multiple focal fibroids in 74% of black women but only 31% of white women between age 35 and 39 years.6 Peddada et al. reported differential fibroid growth by race; the likelihood of rapid tumor growth (>20% increase in volume per 6 months) increased with age in black women, but declined with age among white women (p=.004).12 Black women undergoing surgery for fibroids may also have larger and/or a greater number of fibroids compared with white women. Among hysterectomy patients, black women had a mean uterine weight of 421 grams compared with 319 grams for white women3, and black women undergoing myomectomy were more likely to have >4 fibroids and less likely to have only one (p=.001).13 However, these differences in fibroid characteristics may be due to variation in patient preference for the timing of surgery, rather than true physiologic differences in fibroid development.

Larger size and a greater number of fibroids may result in worse symptoms and surgical outcomes for black women. In a multivariable model that controlled for fibroid risk factors, black women were more likely to have severe disease based on age at diagnosis, severity of menstrual symptoms, and history of fibroid-related surgery (O.R. 5.2, 95%CI 2.0–13.7).10 In a study of 1,200 women with fibroids undergoing hysterectomy, black women were more likely to report severe pelvic pain (59% vs. 41% for whites) and have anemia (56% vs. 38% for whites).3 Roth et al. reported that among 225 women undergoing myomectomy, black women were twice as likely to have a complication compared with white women (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.5,,4.8) and more frequently required a blood transfusion (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.1,5.0).13 However, these differences appeared to be related to the larger size, greater number, and increased co-morbidities among black women. After controlling for these clinical factors, the risk of complications or blood transfusion was not significantly different between black and white women.13

There are multiple possible etiologies for a higher prevalence and more severe presentation of fibroids among black women. Fibroids are hormonally-responsive tumors and some genetic studies have found that black women have unique gene polymorphisms for estrogen synthesis or metabolism, and aberrant expression of micro-RNAs that may lead to gene dysregulation in fibroids.14, 15 For example, the estrogen receptor (ER)-α PP variant has a higher prevalence among black women and has been associated with an increased risk of fibroids.16 One investigation found more polymorphisms in catechol-O-methytransferase, an enzyme involved in estrogen metabolism17, among black women although another study did not confirm this finding.18 Lifestyle and clinical factors such as diet, BMI, smoking, alcohol intake, exercise, diabetes, and hypertension have also been reported in some studies to increase the risk of fibroids.5, 7, 19, 20 Higher rates of these risk factors among black women compared to other racial and ethnic groups may contribute to the incidence of fibroids.21–24 Finally, exposure to bisphenol A has been found to have transcriptional activation and mitogenic effects on fibroids in the Eker rat and CD-1 mouse models. 25–28 Differential exposure to these or other environmental factors by race and ethnicity may contribute to variations in the prevalence of fibroids.29

There is scarce literature on differences in fibroid presentation or treatment among racial and ethnic groups other than black and white women. In the Nurses Health Study II, there were no statistically significant differences in the likelihood of a fibroid diagnosis among Hispanic and Asian women compared with white women.7 Conversely, Templeman et al., applying similar multivariable models, found that Hispanic women had a higher risk of undergoing surgery for fibroids compared with white women (OR 1.3, 95%CI 1.1–1.6).5 In this study, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of fibroids between Asian and white women.5 Future research is needed to examine the prevalence, prognosis, and treatment of fibroids among Hispanic and Asian women to clarify these preliminary findings. Studies are also needed to explore potential genetic causes of fibroid development among Asian and Hispanic women, as have been found among black women.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a common estrogen-dependent condition that may cause dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, and infertility.30 The gold standard for diagnosing endometriosis is a biopsy of abnormal tissue visualized during surgery. Historically, many gynecologists believed that endometriosis was a disease confined almost exclusively to white women.31 Most early studies reported at least double the prevalence of endometriosis among white women and many authors propagated the belief that endometriosis was an extremely rare condition among black gynecology patients.32–35 In the 1970s, several studies reported that over 20% of black women undergoing diagnostic laparoscopy had endometriosis and suggested that endometriosis was overlooked as a cause of pelvic pain due to clinicians’ misperceptions of the low incidence in black women36, 37 However, this early literature was significantly limited by lack of multivariable models to account for clinical and demographic factors that have been associated with receiving a diagnosis of endometriosis.

More recent studies have had conflicting results for racial and ethnic differences in endometriosis. In a study of 330 women undergoing laparoscopic tubal sterilization that accounted for age, parity, income, and payment source in multivariable models, Asian women had almost 9 times greater odds of endometriosis (OR 8.6, 95%CI 1.4–20.1) compared with white women, while the findings for black and Hispanic women were not statistically significant.38 Several other studies of women undergoing infertility evaluation or laparoscopy for pelvic pain have also reported an increase in the prevalence of endometriosis among Asian women compared with white women.39, 40 However, in a prospective cohort study of 90,000 women enrolled in the Nurses Health Study II, Asian women did not have a statistically significant difference in the odds of self-reported endometriosis in a model that controlled for age, parity, and BMI (OR 0.6, 95%CI 0.4–0.9).41 In the same study, black and Hispanic women were each 40% less likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis (OR 0.6, 95%CI 0.4–0.9 for black women, OR0.6, 95%CI 0.4,1.0 for Hispanic).41 Two other studies have found no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of endometriosis between any racial or ethnic group.42, 43

The heterogeneity in findings for differences in the prevalence of endometriosis by race or ethnicity may reflect the diversity of study designs. Some studies have focused on symptomatic patients with infertility or pelvic pain which may under-represent medically-underserved women in racial or ethnic minority groups with poorer access to gynecologic services. Other studies have assessed asymptomatic patients at the time of laparoscopy with variation in the design of multivariable models. Although the epidemiologic evidence is inconclusive, genetic studies have sought an etiology for racial and ethnic differences in endometriosis. Some authors have identified gene mutations among Asian women that may make them more susceptible to endometriosis.44–46 However, a recent literature review found weak data to support an association between genetic polymorphisms and endometriosis.47 Additional research is needed to better understand possible genetic mechanisms associated with racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of endometriosis. Endometriosis has also been associated with environmental exposures such as in utero cigarette smoke and diethylstilbestrol, dioxin, and serum polychlorinated biphenyl congeners (PCB) in some, but not all, studies.48–55 Racial and ethnic differences in these environmental exposures may contribute to variations in endometriosis. However, data is limited for serum levels of these chemicals among Asian women compared to other groups.56 Further research is needed to elucidate possible racial and ethnic differences among women with endometriosis and to determine how these differences affect gynecologic outcomes.

Hysterectomy Rates

Hysterectomy is the most common non-obstetric surgery among women in the United States, with approximately 600,000 procedures performed every year.57, 58 Although some studies have found no association between race/ethnicity and the prevalence of hysterectomy,59, 60 several large investigations have reported higher rates of hysterectomy among black women.61–63 In a nationwide analysis of hospital discharge data, black women were more likely to undergo hysterectomy (6.2 per 1,000) than white women (5.3 per 1,000) overall, and these differences were particularly pronounced in women aged 40–44 years, the most common age range for hysterectomy (16.8 per 1,000 for black women, 10.8 per 1,000 for white women).57 Similarly, among all women aged 40–49 years in Maryland from 1986–1991, the rate of hysterectomy was 12.8 per 1,000 for black women compared with 10.9 per 1,000 for white women.62 Black women in the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study had three times the prevalence of hysterectomy compared with white women (12% versus 4%), and among a diverse sample of 15,160 women enrolled in the Study of Women Across America (SWAN), 30% of black women reported prior hysterectomy compared with 15% of white women.61, 63

Two studies have found significantly higher rates of hysterectomy among black women, irrespective of common clinical and demographic factors that are associated with undergoing hysterectomy. In the CARDIA study, black women were found to have nearly four times the odds of undergoing hysterectomy compared with white women, after controlling for BMI, polycystic ovarian syndrome, tubal ligation, depressive symptoms, age at menarche, education, access to medical care, geographic site, and a diagnosis of fibroids (OR 3.7, 95%CI 2.4, 5.6).61 In a sub-analyses of 1,144 women reporting a history of fibroids, black women were still found to have a higher likelihood of hysterectomy (OR 3.5, 95%CI 2.2, 5.4).61 In the SWAN study, black women were 1.7 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.5, 1.9) after controlling for education, geographic site, age, marital status, fibroids, parity, smoking, and social support.63 Although these studies do not account for all possible confounding factors, they indicate that race appears to have a significant influence on hysterectomy rates after accounting for other demographic and clinical factors. Interestingly, in a diverse cohort of 1,400 women with symptomatic fibroids, abnormal uterine bleeding or pelvic pain, health-related quality-of-life outcomes and attitudes regarding hysterectomy, rather race or ethnicity, were independent predictors of undergoing hysterectomy.64 Further investigation regarding whether or not these issues may explain the increased rate of hysterectomy among black women is warranted.

Poorer access to hysterectomy alternatives or limited knowledge of non-surgical treatments may significantly contribute to the higher rate of hysterectomy among black women. Black women may have lower health literacy resulting in less awareness of non-surgical or minimally-invasive options to manage common gynecologic conditions.65–67 In one qualitative study on hysterectomy in Texas, black women expressed strong desires to avoid or delay surgery for their gynecologic problem and advocated use of alternative therapies.68 Therefore, it is possible that the higher hysterectomy rate reflects less access to non-surgical therapies, despite the desire to avoid hysterectomy. In an evaluation of the appropriateness of hysterectomy among 2,425 patients, black women were more likely to undergo a hysterectomy that was classified as “inappropriate” compared with white women. This association was primarily due to the high risk of inappropriate hysterectomies for women with fibroids, irrespective of race.69 The hysterectomy rate in black women may therefore represent general overuse of a highly discretionary surgical procedure.

There are conflicting data on hysterectomy rates among Hispanic women. Many nationwide surveys collect race data in lieu of ethnicity categories, which significantly limits analyses of Hispanic women. In a cross-sectional study of approximately 25,000 women enrolled in the National Health Interview Survey, 12% of Hispanic women had undergone hysterectomy compared with 23% of non-Hispanic white women. Controlling for multiple demographic and clinical factors, Hispanic women had a 64% lower odds of hysterectomy compared to non-Hispanic white women of similar education level (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.3, 0.4).70 However, Hispanic women had increased odds of hysterectomy in multivariable models (OR 1.6, 95%CI 1.3, 2.1) in the SWAN study.63 These disparate findings may be related to differences in acculturation and/or primary language spoken between the study populations..71–73

The literature is extremely limited on the prevalence of hysterectomy among Asian women because many studies incorporate Asian women into an “other” race category, rather than create a distinct racial grouping.57 The SWAN study enrolled 1,485 Asian women and found that 7% had a history of hysterectomy compared with 15% of white women.63 After accounting for clinical and sociodemographic factors, Asian women had a 56% decreased odds of undergoing hysterectomy (OR 0.4, 95%CI 0.3, 0.6). In a sub-analyses of SWAN participants enrolled in a single health maintenance organization (HMO), Chinese-American women were significantly less likely to report a prior hysterectomy (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.98).63 Acculturation, the adoption of behaviors and beliefs of the dominant culture, may influence the hysterectomy rate among Asians; Chinese-American women educated in China and possibly less accustomed to the routine use of hysterectomy in the United States, had the lowest likelihood of hysterectomy compared to all other groups.63

Hysterectomy Route

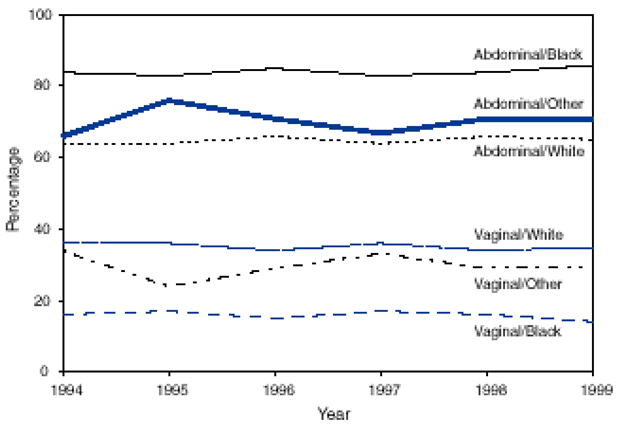

Several analyses have reported a higher prevalence of abdominal hysterectomy versus a laparoscopic or vaginal approach among black, Hispanic, and Asian women compared with white women. In a study of over 500,000 hysterectomy patients, 62% of white women underwent abdominal hysterectomy compared with 83% of black women and 69% of Hispanic women.58 Using national hospital discharge data, Kesharvaz and Marchbanks found higher rates of abdominal hysterectomy and lower rates of vaginal hysterectomy among black women (Figure 1).57 Two analyses utilizing the Nationwide Inpatient Sample reported a lower odds of laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy among all nonwhite groups.64, 74 For instance, black, Hispanic, and Asian women had a 40–50% lower odds of laparoscopic hysterectomy in a multivariable model that accounted for age, income, region, insurance, hospital characteristics, and the diagnosis at surgery (including fibroids).64 These findings are consistent with studies that have reported less laparoscopic surgery compared with laparotomy among black and Hispanic adults undergoing appendectomy and cholecystectomy.75, 76 Provider bias, poorer access to facilities and surgeons where laparoscopy is available, and, possibly, patient preferences may explain these race/ethnicity differences in surgical route.

Figure 1.

Percentage of hysterectomies performed among women age ≥15 years by type of surgical approach and race, 1994–1999

Adapted from Keshavarz et al

Hysterectomy Outcomes

Several studies have found an increased risk of hysterectomy complications among black women compared with white women. Among 53,000 hysterectomies in Maryland, 20% of black women and 13% of white women had one or more peri-operative complications.62 After adjusting for age, hysterectomy route, a diagnosis of cancer or fibroids, co-morbidities, payer, and hospital characteristics, black women were still more likely to have complications (OR 1.4, 95%CI 1.3–1.5) with a significantly increased risk of mortality (OR 3.1, 95% CI 2.0–4.8).62 Hakim et al. also found a higher risk of hysterectomy complications among black women independent of multiple demographic and clinical risk factors (OR 1.7, 95% 1.3–2.1), but the risk among Hispanics was not statistically different from the risk among whites.69 Among nearly 650,000 hysterectomies in California, black and Asian women were more likely to have a surgical complication, irrespective of age, insurance, indication, co-morbidities or other surgeries.77 Hispanic women were less likely to have a surgical complication following vaginal (OR 0.92, 95%CI 0.88–0.96) or total abdominal hysterectomy (OR 0.95, 95%CI 0.93–0.98), but had a slightly increased risk following subtotal hysterectomy (OR 1.11, 95%CI 1.01–1.22).77 Racial and ethnic differences in uterine volume, preoperative health status, or postoperative follow-up care may contribute to disparities in hysterectomy complications and these factors have not been fully evaluated in the current literature.

Oophorectomy at the time of Hysterectomy

Several studies have found higher rates of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) at the time of hysterectomy among white women compared to other racial and ethnic groups. In the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, 50% of white women with a prior hysterectomy had BSO compared with 44% of black women and 40% of Hispanic women, but Asian women had the highest rate of BSO (59%).65 In the CARDIA study, 45% of white women who underwent hysterectomy had a BSO compared with 29% of black women.61 However, these studies did not account for the younger age at hysterectomy among non-white women which decreases the likelihood of undergoing a BSO.

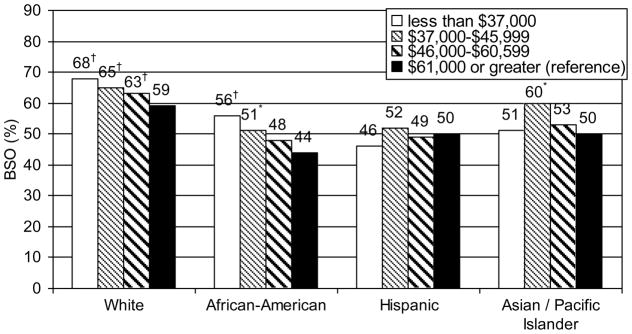

To address the limitations of the uncontrolled studies, a nationwide analysis of approximately 520,000 hysterectomies utilized multivariable models with demographic, clinical, and health system factors to examine race and ethnicity as an independent predictor of BSO.64 In this study, black, Asian, and Hispanic women were less likely to undergo BSO compared with white women. There was a significant interaction between racial and ethnic groups and income with lower income increasing the odds of BSO among white and black women, but not among other groups (Fig. 2). The lower rate of BSO among black women may be associated with a lower use of hormone therapy. 78, 79 Estrogen is frequently used to manage vasomotor symptoms following BSO and a decreased inclination to use estrogen may diminish the desire to undergo BSO among black women. However, there are no studies that specifically examine the cause of racial and ethnic differences in BSO rates; further investigation is needed to determine what patient and provider factors may influence BSO practice patterns.

Figure 2.

Percent of women with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy by race/ethnicity and income in the 2005 Nationwide Inpatient Sample

† p <.001 * p <.05 for comparison to >$61,000, controlled for age, insurance, hysterectomy approach, indication for surgery, region, urban/rural hospital, hospital teaching status and bedsize

Adapted from Jacoby et al

Conclusion

Table 1 demonstrates the significant knowledge gaps on racial and ethnic disparities in fibroids, endometriosis, and hysterectomy. There are high quality and consistent data demonstrating that black women have a higher prevalence of fibroids and present at a younger age compared with white women. Some studies indicate that fibroids in black women are larger, more numerous, cause worse symptoms, and increase myomectomy complications. However, for Hispanic and Asian women, there are extremely limited data on fibroid prevalence and no studies that examine differences in the presentation or prognosis of fibroids. Although several investigators have examined racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of endometriosis, conflicting results preclude a definitive conclusion. Large national databases have consistently found higher rates of hysterectomy among black women. However, the data are less robust on racial and ethnic differences in the route of hysterectomy, complications, and concomitant oophorectomy.

Table 1.

Conclusions and Quality of Evidence for Disparities in Benign Gynecologic Conditions and Surgical Procedures by Race/Ethnicity

| Black | Hispanic | Asian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroids | |||

| Prevalence | ↑ (A) | ↔ (C) | ↔ (C) |

| Age at presentation | ↓ (A) | No studies | No studies |

| Size of fibroids | ↑ (B) | No studies | No studies |

| Number of fibroids | ↑ (B) | No studies | No studies |

| Growth rate of fibroids | ↑ (B) | No studies | No studies |

| Symptom severity | ↑ (B) | No studies | No studies |

| Myomectomy complications | ↑ (B) | No studies | No studies |

| Endometriosis | |||

| Prevalence | ↔ (B) | ↔ (B) | ↔ (B) |

| Hysterectomy | |||

| Rate | ↑ (A) | ↔ (B) | ↓ (C) |

| Abdominal Route | ↑ (B) | ↑ (B) | ↑ (B) |

| Complications | ↑ (B) | ↔ (B) | ↔ (C) |

| Concomitant Oophorectomy | ↓ (B) | ↓ (B) | ↓ (B) |

White women are the reference group. ↑ = higher, greater, or faster, ↓ = lower, less than, or slower; ↔ = available data do not support higher or lower risk. Letter in parenthesis is adapted from the U.S. Preventive Task Force Ratings:

A = There is good evidence and consistent evidence for the association between race/ethnicity and the gynecologic outcome.

B = There is limited or inconsistent evidence to support the association between race/ethnicity and the gynecologic outcome.

C = There is insufficient evidence to support the association between race/ethnicity and the gynecologic outcome.

Future research should focus on further examining possible differences in the prevalence of fibroids and endometriosis by race and ethnicity, as well as exploring potential disparities in the natural history, treatment, and long term morbidity of these conditions. Understanding why some racial and ethnic groups carry an increased burden of disease for these conditions may provide insights into disease mechanisms, and assist in creating new approaches for assessment and treatment. The multi-factorial etiology of racial and ethnic differences in hysterectomy rate and route and the greater surgical morbidity among black women also requires further study with well-designed multivariable models. Although differences in patient preferences and attitudes may in part underlie variations in hysterectomy use, undue physician influence or limited access to hysterectomy alternatives may also play a role. Overall, the current literature on gynecologic health disparities is limited by both quantity and quality. More well-designed studies that examine differences in disease prevalence and surgical rates by race or ethnicity will enrich our understanding of racial and ethnic variation, and lead to further investigations to reduce health disparities.

Acknowledgments

Source of support:

Dr. Jacoby is funded by the Women’s Reproductive Health Research Career Development Program (Grant K12 HD001262)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.AHRQ. National healthcare disparities report. Rockville, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicine Io. Unequal Treatment. Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington D.C: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kjerulff KH, Langenberg P, Seidman JD, Stolley PD, Guzinski GM. Uterine leiomyomas. Racial differences in severity, symptoms and age at diagnosis. J Reprod Med. 1996;41(7):483–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore AB, Flake GP, Swartz CD, et al. Association of race, age and body mass index with gross pathology of uterine fibroids. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(2):90–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Templeman C, Marshall SF, Clarke CA, et al. Risk factors for surgically removed fibroids in a large cohort of teachers. Fertil Steril. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100–7. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(6):967–73. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faerstein E, Szklo M, Rosenshein N. Risk factors for uterine leiomyoma: a practice-based case-control study. I. African-American heritage, reproductive history, body size, and smoking. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z, Peterson HB. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(4):549–55. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huyck KL, Panhuysen CI, Cuenco KT, et al. The impact of race as a risk factor for symptom severity and age at diagnosis of uterine leiomyomata among affected sisters. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):168, e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. Association of physical activity with development of uterine leiomyoma. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(2):157–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(50):19887–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808188105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, Myers ER. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 Pt 1):881–4. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa H, Reierstad S, Demura M, et al. High aromatase expression in uterine leiomyoma tissues of African-American women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(5):1752–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Othman EE, Al-Hendy A. Molecular genetics and racial disparities of uterine leiomyomas. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22(4):589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Hendy A, Salama SA. Ethnic distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha polymorphism is associated with a higher prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in black Americans. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(3):686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Hendy A, Salama SA. Catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism is associated with increased uterine leiomyoma risk in different ethnic groups. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13(2):136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gooden KM, Schroeder JC, North KE, et al. Val153Met polymorphism of catechol-O-methyltransferase and prevalence of uterine leiomyomata. Reprod Sci. 2007;14(2):117–20. doi: 10.1177/1933719106298687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Harlow BL, et al. Risk of uterine leiomyomata in relation to tobacco, alcohol and caffeine consumption in the Black Women’s Health Study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(8):1746–54. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Spiegelman D, et al. Influence of body size and body fat distribution on risk of uterine leiomyomata in U.S. black women. Epidemiology. 2005;16(3):346–54. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000158742.11877.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Differences in prevalence of obesity among black, white, and Hispanic adults - United States, 2006–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(27):740–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurian AK, Cardarelli KM. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(1):143–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1233–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma S, Malarcher AM, Giles WH, Myers G. Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(1):43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook JD, Davis BJ, Goewey JA, Berry TD, Walker CL. Identification of a sensitive period for developmental programming that increases risk for uterine leiomyoma in Eker rats. Reprod Sci. 2007;14(2):121–36. doi: 10.1177/1933719106298401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greathouse KL, Cook JD, Lin K, et al. Identification of uterine leiomyoma genes developmentally reprogrammed by neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Reprod Sci. 2008;15(8):765–78. doi: 10.1177/1933719108322440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodges LC, Hunter DS, Bergerson JS, Fuchs-Young R, Walker CL. An in vivo/in vitro model to assess endocrine disrupting activity of xenoestrogens in uterine leiomyoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;948:100–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newbold RR, Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E. Long-term adverse effects of neonatal exposure to bisphenol A on the murine female reproductive tract. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24(2):253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranjit N, Siefert K, Padmanabhan V. Bisphenol-A and disparities in birth outcomes: a review and directions for future research. J Perinatol. 30(1):2–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houston DE. Evidence for the risk of pelvic endometriosis by age, race and socioeconomic status. Epidemiol Rev. 1984;6:167–91. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavanagh WV. Fertility in the etiology of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1951;61(3):539–47. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(51)91399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott RB, Te LR. External endometriosis--the scourge of the private patient. Ann Surg. 1950;131(5):697–720. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195005000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weed JC. Endometriosis in the Negro. Ann Surg. 1955;141(5):615–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195505000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridley JH. The histogenesis of endometriosis: a review of facts and fancies. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1968;23:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatman DL. Endometriosis and the black woman. J Reprod Med. 1976;16(6):303–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatman DL. Endometriosis in the black woman. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125(7):987–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Poindexter AN., 3rd Epidemiology of endometriosis among parous women. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):983–92. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arumugam K, Templeton AA. Endometriosis and race. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;32(2):164–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1992.tb01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasson HM. Incidence of endometriosis in diagnostic laparoscopy. J Reprod Med. 1976;16(3):135–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirshon B, Poindexter AN, 3rd, Fast J. Endometriosis in multiparous women. J Reprod Med. 1989;34(3):215–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matalliotakis IM, Cakmak H, Fragouli YG, Goumenou AG, Mahutte NG, Arici A. Epidemiological characteristics in women with and without endometriosis in the Yale series. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277(5):389–93. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kado N, Kitawaki J, Obayashi H, et al. Association of the CYP17 gene and CYP19 gene polymorphisms with risk of endometriosis in Japanese women. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(4):897–902. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.4.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duvernoy CS, Rose PA, Kim HM, Kehrer C, Brook RD. Combined continuous ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone acetate does not improve forearm blood flow in postmenopausal women at risk for cardiovascular events: a pilot study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16(7):963–70. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie J, Wang S, He B, et al. Association of estrogen receptor alpha and interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms with endometriosis in a Chinese population. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tempfer CB, Simoni M, Destenaves B, Fauser BC. Functional genetic polymorphisms and female reproductive disorders: part II--endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(1):97–118. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Michels KB, Hunter DJ. In utero exposures and the incidence of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1501–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Louis GM, Weiner JM, Whitcomb BW, et al. Environmental PCB exposure and risk of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):279–85. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayani A, Barel S, Soback S, Almagor M. Dioxin concentrations in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1997;12(2):373–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heilier JF, Nackers F, Verougstraete V, Tonglet R, Lison D, Donnez J. Increased dioxin-like compounds in the serum of women with peritoneal endometriosis and deep endometriotic (adenomyotic) nodules. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(2):305–12. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rier S, Foster WG. Environmental dioxins and endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21(2):145–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Porpora MG, Ingelido AM, di Domenico A, et al. Increased levels of polychlorobiphenyls in Italian women with endometriosis. Chemosphere. 2006;63(8):1361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niskar AS, Needham LL, Rubin C, et al. Serum dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and endometriosis: a case-control study in Atlanta. Chemosphere. 2009;74(7):944–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pauwels A, Schepens PJ, D’Hooghe T, et al. The risk of endometriosis and exposure to dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls: a case-control study of infertile women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(10):2050–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.CDC. Third National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Atlanta (GA): 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kesharvarz HKB, Marchbanks P. Hysterectomy surveillance-United States, 1994–99. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 2002;51:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1091–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000285997.38553.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kjerulff K, Langenberg P, Guzinski G. The socioeconomic correlates of hysterectomies in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(1):106–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Learman LA, Kuppermann M, Gates E, Gregorich SE, Lewis J, Washington AE. Predictors of hysterectomy in women with common pelvic problems: a uterine survival analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):633–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, Lewis CE. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):300–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.133702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kjerulff KH, Guzinski GM, Langenberg PW, Stolley PD, Moye NE, Kazandjian VA. Hysterectomy and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(5):757–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Powell LH, Meyer P, Weiss G, et al. Ethnic differences in past hysterectomy for benign conditions. Womens Health Issues. 2005;15(4):179–86. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuppermann M, Learman L, Schembri M, et al. Predictors of hysterectomy use and satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cf46a0. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2004;291(14):1701–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sentell TL, Halpin HA. Importance of adult literacy in understanding health disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):862–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):175–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shelton AJ, Lees E, Groff JY. Hysterectomy: beliefs and attitudes expressed by African-American women. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(4):732–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hakim RB, Benedict MB, Merrick NJ. Quality of care for women undergoing a hysterectomy: effects of insurance and race/ethnicity. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1399–405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brett KM, Higgins JA. Hysterectomy prevalence by Hispanic ethnicity: evidence from a national survey. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):307–12. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lewis CE, Groff JY, Herman CJ, McKeown RE, Wilcox LS. Overview of women’s decision making regarding elective hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and hormone replacement therapy. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(Suppl 2):S5–14. doi: 10.1089/152460900318722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tortolero-Luna G, Byrd T, Groff JY, Linares AC, Mullen PD, Cantor SB. Relationship between English language use and preferences for involvement in medical care among Hispanic women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15(6):774–85. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hautaniemi SI, Leidy Sievert L. Risk factors for hysterectomy among Mexican-American women in the US southwest. Am J Hum Biol. 2003;15(1):38–47. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abenhaim HA, Azziz R, Hu J, Bartolucci A, Tulandi T. Socioeconomic and racial predictors of undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy for selected benign diseases: analysis of 341487 hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):11–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wolf MS, Knight SJ, Lyons EA, et al. Literacy, race, and PSA level among low-income men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Urology. 2006;68(1):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guller U, Jain N, Curtis LH, Oertli D, Heberer M, Pietrobon R. Insurance status and race represent independent predictors of undergoing laparoscopic surgery for appendicitis: secondary data analysis of 145,546 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(4):567–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.06.023. discussion 75–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith LH, Waetjen LE, Paik CK, Xing G. Trends in the safety of inpatient hysterectomy for benign conditions in California, 1991–2004. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(3):553–61. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318183fdf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weng HH, McBride CM, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, Siegler IC, Bastian LA. Racial differences in physician recommendation of hormone replacement therapy. Prev Med. 2001;33(6):668–73. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marsh JV, Brett KM, Miller LC. Racial differences in hormone replacement therapy prescriptions. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(6):999–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]