Cetn3 inhibits Mps1 kinase activity in vitro and at centrosomes by blocking activating autophosphorylation and can prevent Mps1 from phosphorylating Cetn2 even when Mps1 is present at 10-fold molar excess. Cetn3 also prevents incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles, but mimicking phosphorylation of Cetn2 bypasses the inhibitory effects of Cetn3.

Abstract

Centrins are a family of small, calcium-binding proteins with diverse cellular functions that play an important role in centrosome biology. We previously identified centrin 2 and centrin 3 (Cetn2 and Cetn3) as substrates of the protein kinase Mps1. However, although Mps1 phosphorylation sites control the function of Cetn2 in centriole assembly and promote centriole overproduction, Cetn2 and Cetn3 are not functionally interchangeable, and we show here that Cetn3 is both a biochemical inhibitor of Mps1 catalytic activity and a biological inhibitor of centrosome duplication. In vitro, Cetn3 inhibits Mps1 autophosphorylation at Thr-676, a known site of T-loop autoactivation, and interferes with Mps1-dependent phosphorylation of Cetn2. The cellular overexpression of Cetn3 attenuates the incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles and centrosome reduplication, whereas depletion of Cetn3 generates extra centrioles. Finally, overexpression of Cetn3 reduces Mps1 Thr-676 phosphorylation at centrosomes, and mimicking Mps1-dependent phosphorylation of Cetn2 bypasses the inhibitory effect of Cetn3, suggesting that the biological effects of Cetn3 are due to the inhibition of Mps1 function at centrosomes.

INTRODUCTION

Centrosomes are microtubule-organizing centers that consist of a pair of centrioles surrounded by a pericentriolar matrix. The centrioles duplicate once during S phase of the cell cycle to organize the spindle for the proper segregation of chromosomes during mitosis. Errors in centriole duplication produce extra centrioles that can lead to aneuploidy, which is a major hallmark of cancer (Holland and Cleveland, 2009). Many proteins associated with the centrosome play a direct role in centrosome amplification commonly associated with tumors. For example, the levels of human centrins are elevated in breast tumors containing supernumerary centrosomes (Lingle et al., 1998). Centrin was first identified in the green alga Tetraselmis striata as a 20-kDa phosphoprotein (Salisbury et al.,1984). Centrins belong to the highly conserved EF-hand superfamily of small, calcium-binding proteins and are commonly associated with centrosomal structures (Wright et al., 1985; Huang et al., 1988; Ogawa and Shimizu, 1993). Humans possess three distinct centrin genes. Centrin 1 (Cetn1) is only expressed in male germ cells, neurons, and other ciliated cells, whereas centrins 2 and 3 (Cetn2 and Cetn3) are ubiquitously expressed in somatic cells (Middendorp et al., 1997; Wolfrum and Salisbury, 1998; Hart et al., 1999; Gavet et al., 2003). Centrin 4, first described in mouse, is an unexpressed pseudogene in humans (Gavet et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2010). On the basis of recent evolutionary analysis, two centrin subfamilies have been defined. Members of the first subfamily, which includes human Cetn3, are related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC31, and members of the second subfamily, which include human Cetn1 and Cetn2, are more homologous to the Chlamydomonas centrin (Hodges et al., 2010; Vonderfecht et al., 2012).

In budding yeast, Cdc31p localizes to the half-bridge of the spindle pole body (SPB; analogous to the centrosome; Spang et al., 1993), and CDC31 mutations lead to SPB duplication defects (Baum et al., 1986). Depletion of Cen3p (a Cdc31p family member) in Paramecium tetraurelia leads to a deficiency in the anterior left filament, which prevents premature disengagement and tilting of newly assembled basal bodies, affecting their docking at the cell surface (Jerka-Dziadosz et al., 2013). In Tetrahymena thermophila, Cen1 and Cen2 have similar but not identical functions in basal body maintenance and orientation, as overexpression of CEN1 (a Cetn2 family member) fails to rescue the loss of basal bodies and orientation defects seen in Cen2∆ (a Cdc31p family member) cells (Vonderfecht et al., 2012). These studies suggest an important role of centrins in basal body/centriole assembly and maintenance throughout evolution. However, a study in which all three centrins were deleted in avian DT40 cells reported no detectable effect on centriole duplication or cell cycle progression, although this approach revealed a role for centrins in nucleotide excision repair (Dantas et al., 2011), consistent with a known interaction between centrin and the xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein (Araki et al., 2001; Thompson et al., 2006; Klein and Nigg, 2009).

Vertebrate Cetn2 is predominantly cytoplasmic but also localizes to the distal lumen of centrioles (Errabolu et al., 1994; Paoletti et al., 1996; Azimzadeh and Marshall, 2010), and Cetn3 has been shown to reside at centrioles (Middendorp et al., 2000) and the pericentriolar matrix (Baron et al., 1992). Cetn2 and Cetn3 have important roles in centriole duplication and cell division and do not appear to be functionally redundant. For example, recombinant human Cetn3 inhibits centrosome duplication in Xenopus embryos (Middendorp et al., 2000), an effect that was not elicited by recombinant human Cetn2 (Paoletti et al., 1996; Middendorp et al., 2000). Furthermore, exogenous expression of human Cetn3 in budding yeast cells inhibits SPB duplication and blocks cell growth (Middendorp et al., 2000). It is not clear whether these effects reflect an inhibitory function for Cetn3 or a dominant effect from overexpression of a distantly related orthologue, but overexpression of human Cetn2 in yeast does not affect cell growth, and we demonstrated that Cetn2 and Cetn3 do not have the same effect on centriole biogenesis when overexpressed in vertebrate cells (Yang et al., 2010).

The function of mammalian Cetn2 in centriole assembly remains to be clarified. Initial studies suggested that Cetn2 was required for centriole duplication, with Cetn2 depletion causing a G1 cell cycle delay (Salisbury et al., 2002). However, more recent studies showed that Cetn2 is not required for the recruitment of HsSAS-6 to procentrioles (Strnad et al., 2007) and that codepletion of Cetn2 and Cetn3 does not prevent Plk4-induced centriole overproduction or the recruitment of centriolar proteins such as CPAP, Cep135, and CP110 to nascent centrioles (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007). Moreover, centrioles persist in human cells where Cetn2 has been disrupted using CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Prosser and Morrison, 2015). However, it should be noted that phenotypic dispensability does not rule out a physiological role for Cetn2 at centrioles. Indeed, we confirmed that whereas centrioles can be assembled in the absence of Cetn2, incorporation of CP110 into nascent centrioles is delayed in Cetn2-depleted cells (Yang et al., 2010). Cetn2 also regulates the removal of CP110 from the distal end of centrioles, and both the distal ends of centrioles and primary ciliogenesis are disrupted in Cetn2 null cells (Prosser and Morrison, 2015). Of interest, centrins are highly phosphorylated in human breast tumors that have extra centrosomes (Lingle, 1998). Both Aurora A and protein kinase A are known to phosphorylate the same site (Ser-170) within Cetn2, which regulates Cetn2 stability, Aurora A induced centrosome amplification, and centriole separation (Lutz et al., 2001; Lukasiewicz et al., 2011). In addition, the mitotic kinase Mps1 is also known to phosphorylate Cetn2 (Yang et al., 2010), and the CDC25B phosphatase stabilizes a pool of Mps1 that in turn increases the levels of Cetn2 at the centrosome and generates extra Cetn2 foci (Boutros et al., 2013). Indeed, the mutation of in vitro Mps1 phosphorylation sites within Cetn2 modulates its ability to incorporate into centrioles (Yang et al., 2010; Dantas et al., 2013), as well as its ability to support either Mps1- or Cetn2-dependent centriole overproduction (Yang et al., 2010). These data support the idea that Cetn2 function is regulated by direct Mps1 phosphorylation. Mps1 can also phosphorylate Cetn3 in vitro, although Cetn3 is phosphorylated to a much lesser extent than Cetn2 (Yang et al., 2010). However, overexpression of Cetn3 did not lead to excess centrioles, suggesting that Cetn2 and Cetn3 are not functionally redundant (Yang et al., 2010). In this study, we demonstrate that Cetn3 binds to Mps1 directly and exhibits the properties of an Mps1 inhibitor since it prevents both Mps1 autophosphorylation on a key regulatory site (Thr-676) and Cetn2 phosphorylation. In addition, we demonstrate that Cetn3 antagonizes centriole assembly in cells through inhibition of Mps1 and by blocking the incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles.

RESULTS

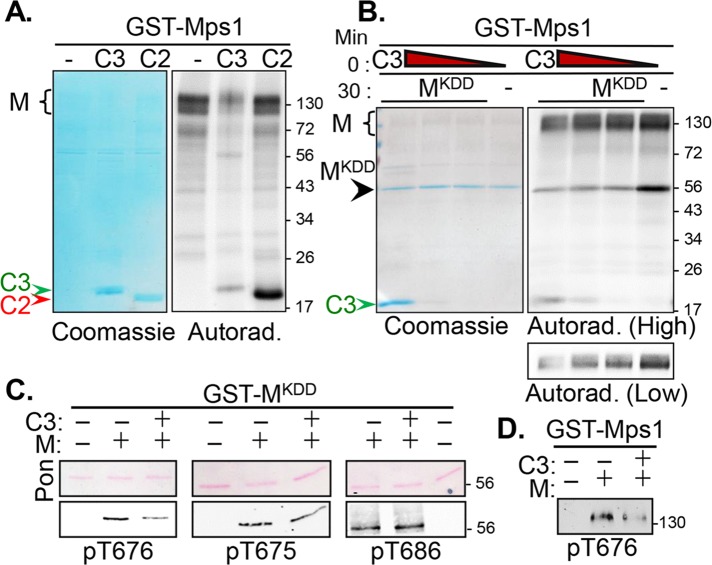

Cetn3 inhibits activating transautophosphorylation within the Mps1 kinase domain

We previously identified Cetn2 and Cetn3 as substrates phosphorylated by Mps1 (Yang et al., 2010). We noticed that whereas Mps1 phosphorylated Cetn3 to a lesser extent than Cetn2, Cetn3 inhibited Mps1 autophosphorylation (Figure 1A). Some Mps1 autophosphorylation persisted in the presence of Cetn3, which is expected, given that bacterially expressed Mps1 is highly active and heterogeneously autophosphorylated on at least 16 different sites (Mattison et al., 2007; Tyler et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009), and we detected as many as 25 sites of in vitro phosphorylation (unpublished data). Moreover, residual Mps1 autophosphorylation is retained at centrosomes even in the presence of the Mps1 inhibitor reversine (von Schubert et al., 2015). Because Mps1 autoactivates through autophosphorylation within its kinase domain (Mattison et al., 2007; Chu et al., 2008; Tyler et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009), we tested the effect of Cetn3 on the ability of full-length glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Mps1 to phosphorylate a kinase dead (KD) version of the Mps1 kinase domain (Mps1KDD; Mps1 residues 515–794 containing the D664A mutation, which renders Mps1 catalytically inactive). When compared with Mps1 alone, Cetn3 significantly decreased the phosphorylation of Mps1KDD in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B, lanes 1–3 vs. lane 4). Of interest, phosphorylation of Mps1KDD was inhibited whether Cetn3 was preincubated with Mps1KDD before addition of GST-Mps1 or preincubated with GST-Mps1 before addition of Mps1KDD (Supplemental Figure S1). However, Cetn3 could not prevent phosphorylation of Mps1KDD that had been preincubated with GST-Mps1 (Supplemental Figure S1), suggesting that Cetn3 cannot reverse Mps1 transphosphorylation. A shorter exposure highlighting the potent inhibition of Mps1 autophosphorylation by Cetn3 is presented at the bottom of Figure 1B.

FIGURE 1:

Cetn3 is an inhibitor of Mps1 catalytic activity. Recombinant GST-Mps1 (M) was used for in vitro kinase assays. (A) Mps1 was incubated alone (M) or with His-Cetn2 (C2) or His-Cetn3 (C3) for 60 min, and kinase assays were analyzed by autoradiography after SDS–PAGE. Cetn2 (red arrowhead) is phosphorylated to a greater extent than Cetn3 (green arrowhead), but only Cetn3 markedly reduces Mps1 autophosphorylation (black caret). (B) GST-Mps1 (M) was either incubated alone for 60 min (–) or preincubated with decreasing amounts of C3 (1.0, 0.5, or 0.1 μg) for 30 min before the addition of 1 μg of GST-tagged kinase-dead Mps1 kinase domain (MKDD) for an additional 30 min. Assays were analyzed as described. Coomassie staining (showing equal loading of MKDD) and a 30-min autoradiographic exposure (High) are shown. Cetn3 (green arrowhead) reduces transphosphorylation of MKDD (black arrowhead) by full-length Mps1 (black caret) over a wide concentration range. Bottom, a lower exposure of Mps1 autophosphorylation (Low). (C, D) Kinase assays were performed as in B but in the absence of radiolabeled ATP and analyzed by immunoblotting with phosphospecific antibodies recognizing pT676, pT675, or pT686. (C) Ponceau-S (Pon)–stained membranes (confirming equal loading of MKDD) and immunoblots showing the effect of Cetn3 on staining of MKDD with the indicated antibodies. (D) Effect of Cetn3 on staining of full-length GST-Mps1 with pT676 . Cetn3 decreased the phosphorylation of GST-Mps1 and MKDD at T676. The numbers on the right of the gels represent the molecular weight in kilodaltons.

We next tested whether Cetn3 inhibits specific autophosphorylation events, using phosphospecific antibodies that recognize Mps1 phosphorylated at T675, T676, or T686 (Tyler et al., 2009). Of interest, Cetn3 led to a marked decrease in the ability of GST-Mps1 to phosphorylate Mps1KDD at T676, a regulatory T-loop site that controls Mps1 activity ([0.53 ± 0.03]-fold), but was less able to reduce phosphorylation of Mps1KDD at T675 (0.73 ± 0.02-fold) and had no significant effect on phosphorylation of Mps1KDD at T686 ([0.97 ± 0.04]-fold; Figure 1C). Cetn3 also reduced T676 phosphorylation in full-length GST-Mps1 ([0.47 ± 0.07]-fold; Figure 1D) to a similar degree as in Mps1KDD. Together these observations suggest that Cetn3 inhibits both Mps1 kinase activity and Mps1 autophosphorylation in vitro.

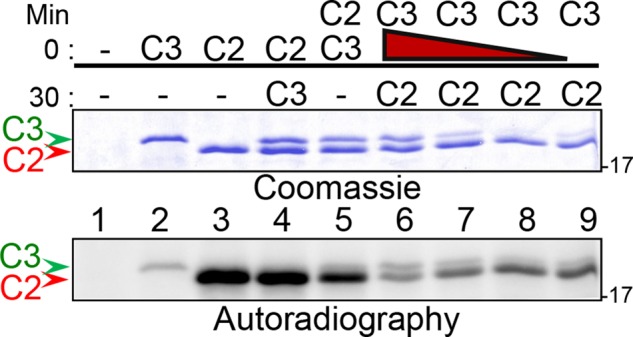

To determine whether Cetn3 could also affect the ability of Mps1 to phosphorylate substrates other than itself, we coincubated Mps1 with both Cetn2 and Cetn3 (Figure 2). When Cetn2 was incubated with Mps1 for 30 min before the addition of Cetn3, there was little change in Cetn2 phosphorylation (Figure 2, lane 4 vs. lane 3). However, Cetn2 phosphorylation was noticeably reduced when Cetn2 and Cetn3 were coincubated simultaneously with Mps1 (Figure 2, lane 5 vs. lane 4), and dramatically reduced when Mps1 was preincubated with Cetn3 for 30 min before adding Cetn2 (Figure 2, lanes 6–9), suggesting that Cetn3 reduced Cetn2 phosphorylation by targeting Mps1 rather than Cetn2. Moreover, inhibition did not appear to be competitive, since Cetn3 markedly reduced the phosphorylation of Cetn2 over a wide range of concentrations (Figure 2), and Cetn2 phosphorylation was not completely restored even at Cetn3 concentrations that were 10-fold lower than that of Mps1 (Supplemental Figure S2, A and B). Consistent with our observation that Cetn3 is a general Mps1 inhibitor, Cetn3 also caused a significant reduction in phosphorylation of the generic kinase substrate myelin basic protein (MBP; Supplemental Figure S2C), indicating that the inhibitory effect of Cetn3 was not exclusive to the specific substrate Cetn2.

FIGURE 2:

Cetn3 inhibits the phosphorylation of Cetn2. Recombinant GST-Mps1, His-Cetn2 (C2, red arrowhead), and His-Cetn3 (C3, green arrowhead) were used for in vitro kinase assays. Kinase assays were incubated for a total of 60 min. Proteins indicated above the line (0 min) were added at the initiation of the reaction and were present for the entire reaction, whereas proteins indicated below the line (30 min) were added to the reaction after 30 min. The red triangle above lanes 6–9 indicates decreasing amounts of C3 (1, 0.5, 0.2, and 0.05 μg) incubated with Mps1 for 30 min before addition of C2 for the remaining 30 min. After 60 min, kinase assays were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. Coomassie staining showing loading of C2 and C3 and 30-min autoradiograph exposure of the gel. The greatest reduction in Cetn2 phosphorylation is observed when Cetn3 is preincubated with Mps1 before the addition of Cetn2, and Cetn3 reduces phosphorylation of Cetn2 over a wide concentration range. The numbers on the right of the gels represent the molecular weight in kilodaltons.

Cetn3 does not prevent the interaction between Cetn2 and Mps1

We next sought to determine whether purified centrin proteins bound to Mps1. We initially incubated recombinant GST-Mps1 with recombinant His-Cetn2 and/or His-Cetn3. Cetn3 showed negligible binding to GST alone but bound to GST-Mps1 in the presence or absence of ATP (Figure 3A). It has been reported that Mg ions bind to the N-terminal domain of Cetn3 and may facilitate target peptide recognition (Cox et al., 2005), and indeed we found that the binding of Cetn3 to GST-Mps1 was enhanced in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2 ([2.59 ± 0.91]-fold; Figure 3B). Cetn2 also bound to GST-Mps1, and this binding was not enhanced by CaCl2, a known modulator of Cetn2 function (Figure 3C). Cetn2 and Cetn3 also bound to catalytically inactive (and nonphosphorylated) GST-Mps1KD (Figure 3D), suggesting that the binding does not require Mps1 kinase activity, phosphorylated Mps1, or phosphorylation of Cetn2 or Cetn3 by Mps1. Given that both Cetn2 and Cetn3 can bind to Mps1, we next tested the effect of Cetn3 on the interaction between Mps1 and Cetn2. Cetn2 and Cetn3 were incubated with GST, GST-Mps1, or GST-Mps1KD either alone (Figure 3E, lanes 1 and 2) or together (co, Figure 3E, lanes 3) for 60 min, or Cetn3 was preincubated with GST, GST-Mps1, or GST-Mps1KD for 30 min before addition of Cetn2 (Figure 3E, lane 4). Of interest, coincubation of Cetn2 and Cetn3 with GST-Mps1 led to an enhanced binding of Cetn2 to GST-Mps1 ([3.39 ± 1.96]-fold, Figure 3E, M, lane 3 vs. lane 1) that was not observed if Cetn3 had been preincubated with Mps1 before addition of Cetn2 (Figure 3E, M, lane 4). Of interest, activated Mps1 was required for this enhanced binding because coincubation with Cetn3 did not enhance the binding of Cetn2 to GST-Mps1KD (Figure 3E, MKD, lane 3 vs. lane 4), although catalytic activity was not required for binding per se (Figure 3E, MKD, lanes 1 and 2). To summarize, Cetn2 and Cetn3 both bind to Mps1 independently of kinase activity or phosphorylation status of Cetn2 or Cetn3. Second, the binding of Cetn3 to Mps1 is enhanced by MgCl2. Finally, the binding of Cetn2 to Mps1 is enhanced by Cetn3 in vitro. Together our observations that Cetn3 inhibits Mps1 autophosphorylation at T676 and inhibits phosphorylation of Cetn2 and MBP without preventing the binding of Cetn2 suggest that Cetn3 acts as a noncompetitive allosteric inhibitor of Mps1 kinase activity in vitro.

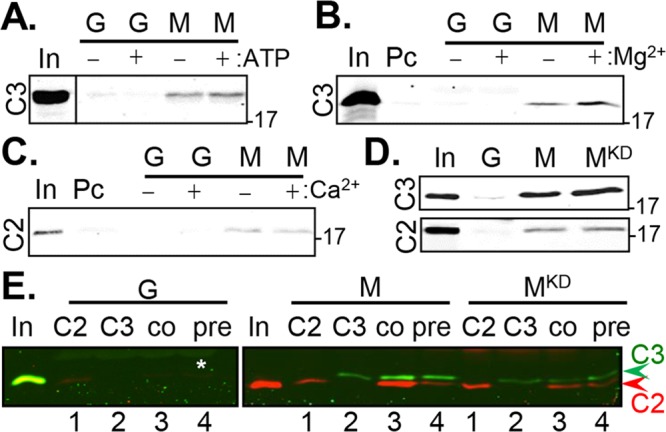

FIGURE 3:

Cetn3 does not prevent the binding of Cetn2 to Mps1. (A–C) His-Cetn3 (C3) or His-Cetn2 (C2) were incubated for 60 min with GST (G) or GST-Mps1 (M) immobilized on glutathione Sepharose beads in the presence (+) or absence (–) of ATP, MgCl2, or CaCl2 as indicated. Bead-bound material was isolated by centrifugation, washed, and analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies recognizing C2 or C3 as indicated. (A) C3 binds to Mps1, and the binding does not require ATP; the input (In) lane was separated by a blank lane, which has been cropped out as indicated by the line. (B) The binding of Cetn3 to Mps1 is enhanced by MgCl2 ([2.59 ± 0.91]-fold; input shows 1% of lysate used for pull down); Pc, preclearing beads (e.g., binding to beads alone). (C) C2 binds to Mps1, and the binding is not affected by CaCl2. (D) The binding of C2 and C3 to Mps1 does not require catalytic activity. C2 or C3 was incubated with GST (G), GST-Mps1 (M), or GST-Mps1KD (MKD). (E) Cetn3 does not prevent the binding of Cetn2 to Mps1. C2 (red) and C3 (green) were incubated with bead-bound GST (G), GST-Mps1 (M), or GST-Mps1KD (MKD) as follows: 1) C2 was incubated with G, M, or MKD alone (C2); 2) C3 was incubated with G, M, or MKD alone (C3); 3) C2 and C3 were coincubated with G, M, or MKD (co); 4) C3 was preincubated with G, M, or MKD for 30 min, followed by the addition of C2 for an additional 30 min (pre). C2 (red) and C3 (green) were imaged simultaneously using the LI-COR Odyssey scanner. The input (In) for Cetn2 was run on the gel with GST, whereas that for Cetn3 was run on the gel with GST-Mps1 and GST-Mps1KD. The numbers on the right of the gels represent the molecular weight in kilodaltons.

Endogenous Cetn3 and Cetn2 bind to endogenous Mps1

We next sought to determine whether the complex interactions discovered between Mps1 and centrins in vitro are also observed in living cells. To accomplish this, we first overexpressed green fluorescent protein (GFP)–biotin, GFP-biotin-Mps1, or GFP-biotin-Mps1KD in HEK 293 cells and performed pull-down experiments with streptavidin beads (Figure 4A). No binding of Cetn3 to GFP-biotin was observed, but Cetn3 bound to both GFP-biotin-Mps1 and kinase-dead GFP-biotin-Mps1 (Figure 4A). An interaction between Cetn2 and GFP-biotin-Mps1 was also observed, but it was weak and inconsistent (unpublished data). We also confirmed reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation between endogenous Cetn3 and Mps1 in both HeLa (Figure 4B) and HEK 293 cells (Supplemental Figure S3), validating a physiological interaction between Mps1 and Cetn3. Cetn3 appeared to interact with a minor form of Mps1 that had a slightly higher mobility and was of lower abundance than the bulk of cellular Mps1. This is most apparent in HEK 293 cells (Supplemental Figure S3) but can also be seen in HeLa cell lysates (Figure 4B). Although we failed to observe a consistent interaction between Cetn2 and GFP-biotin-Mps1, we did observe immunoprecipitation of Cetn2 by endogenous Mps1 (Figure 4C). Given that the majority of both Mps1 (Kasbek et al., 2007) and Cetn2 (Paoletti et al., 1996) is noncentrosomal, it is possible that the large noncentrosomal pools of endogenous Cetn2 and overexpressed GFP-biotin-Mps1 mask an interaction between a much smaller centrosomal pool. Finally, endogenous Cetn2 and Cetn3 also exhibited reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation (Figure 4D, normalized for equal Cetn3 loading), although we could not rule out the possibility that Cetn2 might be binding to a Cetn3:Mps1 complex. Of interest, a large amount of Cetn3 coprecipitated with Cetn2 compared with the relatively small amount of Cetn2 that coprecipitated with Cetn3.

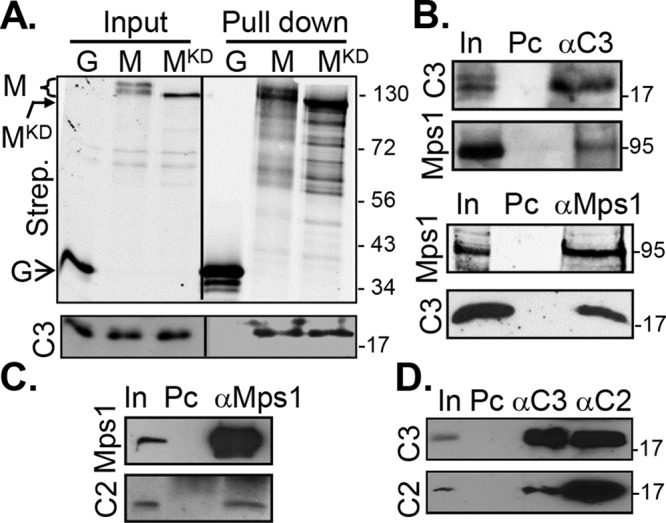

FIGURE 4:

Cetn3 and Cetn2 bind to Mps1 in human cells. (A) Cetn3 binds equally well to wild-type and kinase-dead Mps1 in cells. Lysates from S phase–arrested HEK 293 cells expressing GFP-biotin (G), GFP-biotin-Mps1 (M), and GFP-biotin-Mps1KD (MKD) were incubated with streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. The streptavidin pull downs were then analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. The open arrow indicates the position of GFP, the bent, closed arrow indicates the position of MKD, and the bracket indicates full-length Mps1. (B–D) Lysates from S phase–arrested HeLa cells were incubated with rabbit antibodies against Mps1 (αMps1), Cetn2 (αC2), or Cetn3 (αC3), precipitated with protein G beads, and then analyzed by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting with mouse antibodies against Mps1 or Cetn3 (C3) or rabbit antibody against Cetn2 (C3) as indicated. (B) Endogenous Mps1 and Cetn3 demonstrated reciprocal co-IP; top, Mps1 coimmunoprecipitates (coIPs) with rabbit anti-Cetn3 (αC3); bottom, Cetn3 (C3) coIPs with rabbit αMps1 (αMps1). (C) Cetn2 (C2) coIPs with endogenous Mps1; bottom, uppermost band represents protein G used in the immunoprecipitation (which leached from the magnetic beads). (D) Reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation is observed between endogenous Cetn2 and Cetn3; precipitated material was normalized for equal loading of Cetn3. In, input, 0.5% or 1% of the lysate; Pc, preclearing beads (e.g., binding to beads alone). The numbers on the right of the gels represent the molecular weight in kilodaltons.

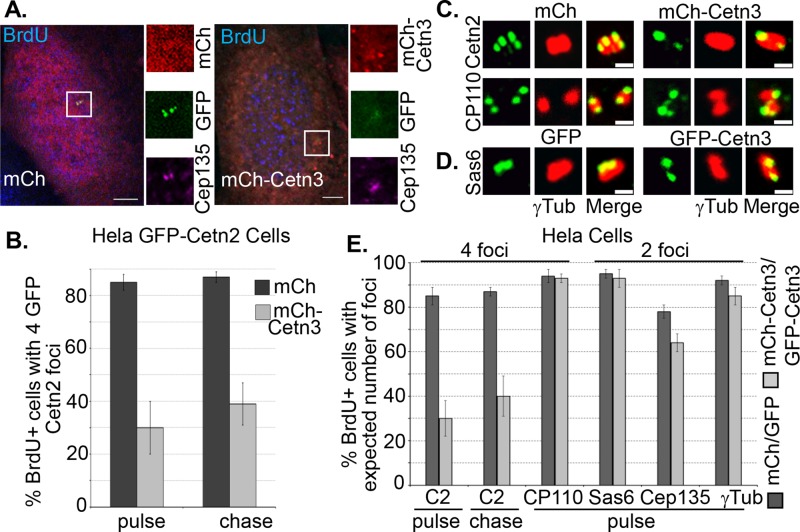

Cetn3 overexpression inhibits incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles

To determine whether Cetn3 plays a role in centriole assembly, we first used a 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) pulse-chase approach to assess whether overexpression of Cetn3 could influence centriole biogenesis during S phase. Because cells enter S phase with two Cetn2-positive centrioles and quickly assemble new centrioles capable of recruiting Cetn2, the majority of cells that incorporate BrdU during a short pulse contain four Cetn2-positive foci (Yang et al., 2010; Majumder et al., 2012). In cases in which cells have not completed some aspect of centriole assembly during a short BrdU pulse, including a chase period allows us to determine whether they could do so if given additional time. For example, we previously showed that after an initial BrdU pulse, Cetn2-depleted cells exhibit a defect in the incorporation of CP110 into new centrioles; however, after the chase period, CP110 incorporation was equivalent to that in control cells (Yang et al., 2010). We initially examined the effect of Cetn3 on centriole biogenesis in a validated HeLa GFP-Cetn2 cell line (Yang et al., 2010). GFP-Cetn2 causes centriole overproduction during a prolonged S phase arrest (Yang et al., 2010). However, centriole numbers remain largely normal in unarrested populations such as used in this experiment, so that after a 4-h pulse with BrdU, ∼85% of BrdU-positive HeLa GFP-Cetn2 cells expressing mCherry (mCh) alone had four GFP-Cetn2 foci, and only ∼15% had two GFP-Cetn2 foci (Figure 5, A and B). However, mCh-Cetn3 expression increased the percentage of BrdU- positive cells with two Cetn2 foci roughly fivefold to ∼70% (Figure 5, A and B). The mCh-Cetn3 and GFP-Cetn3 proteins (see below) were overexpressed roughly 12- to 15-fold relative to endogenous Cetn3, as judged by in-cell quantification (Supplemental Figure S4). The percentage of BrdU-positive cells expressing mCh-Cetn3 that had two Cetn2 foci decreased only slightly to ∼60% after a 4-h chase period (Figure 5B), suggesting that Cetn3 overexpression blocks the incorporation of GFP-Cetn2 into new centrioles rather than simply causing a delay. To determine whether overexpression of Cetn3 also affects the incorporation of endogenous Cetn2, we carried out a similar 5-ethynyl-2´-deoxyuridine (EdU) pulse chase in HeLa cells using an antibody that recognizes Cetn2. Whereas only ∼13% of EdU-positive HeLa cells expressing mCh alone had two Cetn2 foci, this percentage increased to 55% in cells expressing mCh-Cetn3 after the initial EdU pulse and decreased only slightly to 48% after a 4-h chase (Figure 5E). This demonstrates that Cetn3 overexpression inhibits the incorporation into newly assembling centrioles of both endogenous Cetn2 and GFP-Cetn2. To determine whether the reduction in Cetn2-positive foci represents a failure to assemble new centrioles or a failure to incorporate Cetn2 into newly assembled centrioles, we assessed a variety of centriolar markers. Although there was a very slight reduction in the number of foci for γ-tubulin (a pericentriolar marker) and Cep135 (a proximal centriole marker), overexpression of Cetn3 did not cause any significant reduction in the number of foci for HsSAS-6 (a procentriolar marker) or CP110 (a distal centriole marker), suggesting that the primary effect of Cetn3 overexpression during the canonical centriole assembly cycle is to interfere with proper incorporation of Cetn2 into newly assembled centrioles (Figures 5, C–E).

FIGURE 5:

Overexpression of Cetn3 inhibits incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles in asynchronously growing cells. (A, B) Overexpression of Cetn3 reduces the percentage of S phase cells that have incorporated GFP-Cetn2 into new centrioles. HeLa GFP-Cetn2 cells were transfected with mCherry (mCh) or mCh-Cetn3, incubated with BrdU for 4 h, and then fixed and processed for IIF either after the BrdU pulse or after a 4-h chase in the absence of BrdU. (A) Representative images of BrdU-positive HeLa GFP-Cetn2 cells showing mCh or mCh-Cetn3 (red), GFP-Cetn2 (GFP, green), and Cep135 (purple). Bar, 5 μm. In all images, insets show digitally magnified centrosomes indicated by boxes. (B) Bar graph showing percentage of BrdU-positive cells with four GFP-Cetn2 foci. (C–E) Overexpression of Cetn3 inhibits the incorporation of endogenous Cetn2 into centrioles but does not affect the incorporation of CP110 or HsSAS-6. HeLa cells were transfected with mCh or mCh-Cetn3, or GFP or GFP-Cetn3, and then incubated with EdU for 4 h and fixed and processed for IIF with various antibodies either after the EdU pulse or after a 4-h chase in the absence of EdU. (C) Representative images of centrosomes from EdU-positive mCh- and mCh-Cetn3–transfected HeLa cells stained with either Cetn2 or CP110 (green) and γ-tubulin (red). Bar, 1 μm. (D) Representative images of centrosomes from EdU-positive GFP- and GFP-Cetn3–transfected HeLa cells stained with HsSAS-6 (green) and γ-tubulin (red). (E) Percentage of EdU-positive cells with four foci for Cetn2 or CP110 and two foci for HsSAS-6, Cep135, and γ-tubulin. Values in B and E represent the mean ± SD for triplicate samples for which at least 75 cells were counted per replicate.

Cetn3 depletion promotes centriole reduplication

We next investigated the effects of small interfering RNA (siRNA)–mediated depletion of Cetn3, using a previously validated Cetn3-specific siRNA (siCetn3) sequence (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007). Transfection of siCetn3 caused ∼80% reduction in Cetn3 protein levels in S phase–arrested HeLa cells, as quantified by immunoblotting (Figure 6A). Consistent with the hypothesis that endogenous Cetn3 acts to inhibit Cetn2 localization and function, depleting Cetn3 led to a twofold increase in the number of hydroxyurea (HU)-arrested HeLa cells with more than four Cetn2 foci as compared with control siRNA cells (Figure 6, B–D). There was a concomitant increase in the number of γ-tubulin foci (Figure 6, B and C), suggesting that even though overexpression of Cetn3 did not inhibit centriole assembly per se (see Figure 5), Cetn3 depletion generated excess Cetn2-containing structures capable of recruiting γ-tubulin in S phase–arrested HeLa cells. To determine whether these structures were indeed centrioles, we performed a serial-section electron microscopic (EM) analysis. Although we did not observe excess centrioles in any control cell (n = 7 cells), excess centrioles were readily apparent in Cetn3-depleted cells (Figure 6D; n = 8 cells, two of which had more than four centrioles).

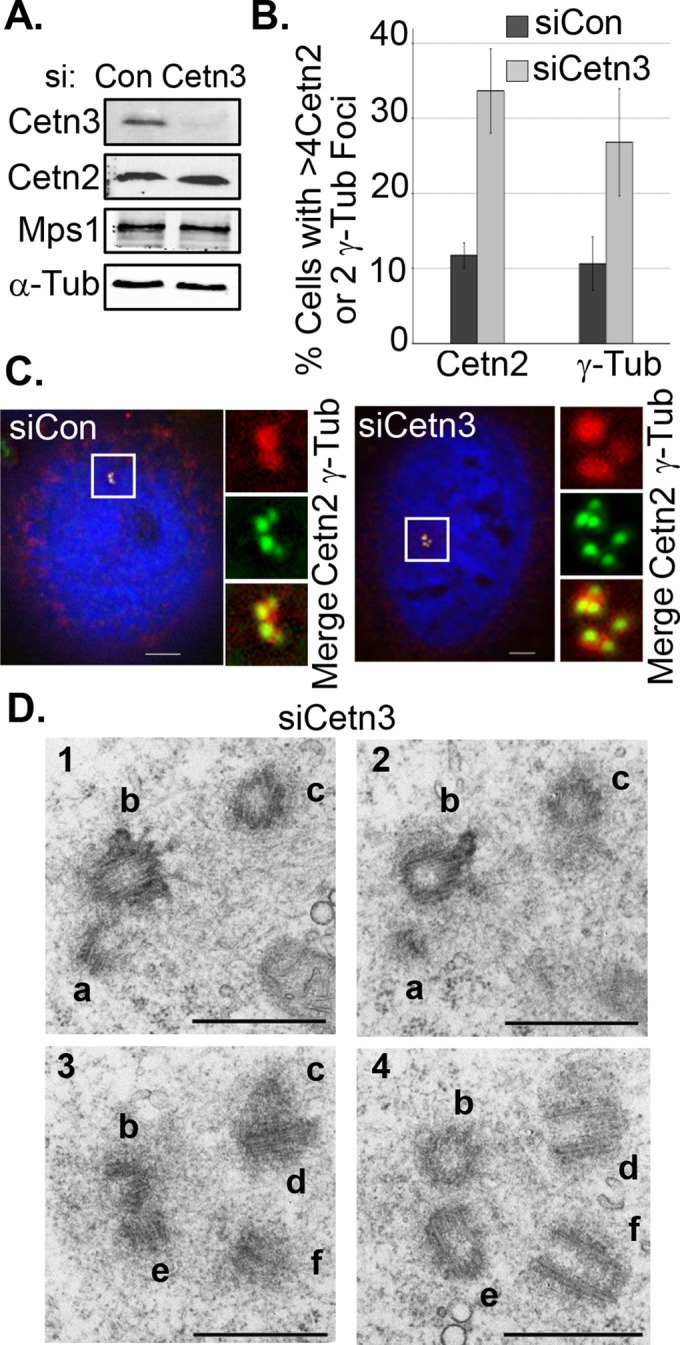

FIGURE 6:

Cetn3 depletion leads to centriole reduplication in S phase–arrested cells. HeLa cells were transfected with control (siCon) or Cetn3-specific (siCetn3) siRNAs and then arrested in S phase for 48 h with HU as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Immunoblot comparing whole-cell levels of Cetn3, Mps1, and Cetn2 in siCetn3 and siCon lysates, with α-tubulin (α-Tub) as a loading control. siCetn3 caused an 80–90% reduction in Cetn3 protein levels, with no change in whole-cell protein levels of Mps1 and Cetn2. (B) Percentage of S phase–arrested cells with more than four Cetn2 foci or more than two γ-tubulin foci. (C) Representative images of S phase–arrested, siRNA-transfected HeLa cells showing DNA (blue), Cetn2 (green), and γ-tubulin (red). (D) Representative electron micrographs of serial sections from a HeLa cell transfected with siCetn3, showing extra centrioles (six individual centrioles are labeled a–f; n = 8, two of which had excess centrioles, compared with 0 of 7 control cells). Bar, 500 nm.

Of interest, knockdown of Cetn3 also led to a fivefold increase in the number of cells that displayed long, linear, Cetn2-positive structures (Figure 7, A and B) that were also positive for acetylated tubulin and CP110. These structures often occurred close to the centrosome but were also found at sites some distance from the centrosome. Similar structures were recently described in GFP-POC5–overexpressing DT40 cells but did not contain tubulin (Dantas et al., 2013). Whereas our EM analysis detected long, linear structures that appeared to contain bundled fibers in Cetn3-depleted cells, we observed similar structures (albeit shorter and more diffuse) in control cells (unpublished data). Of interest, knockdown of Cetn3 also led to a 10-fold increase in mitotic cells despite the continued presence of HU (Figure 7, C and D). Most of these mitotic cells displayed an abnormal multipolar morphology, suggesting that they had arisen from cells that had undergone centriole overproduction before entering mitosis. Because they occur in HU-arrested cells, the multipolar spindles are indicative of a cell cycle defect. However, the number of mitotic cells was quite small, and >90% of those mitotic cells we observed contained excess centrioles, suggesting that the cell cycle defect did not contribute to the appearance of excess centrioles. Indeed, centriole numbers are relatively normal before the onset of S phase arrest (unpublished data), and our EM analysis confirmed the presence of multiple daughter centrioles associated with a single mother centriole (e.g., Figure 6D, centrioles a, b, and e), a bona fide defect in centriole assembly that is unlikely to arise through failure in cytokinesis. Thus the most likely implication of our data is that excess centrioles arose through a defective centriole assembly process. The increase in abnormal mitotic cells in HU-arrested populations suggests that Cetn3 may also play a role in cell cycle regulation similar to the known role of Cetn2 in the DNA damage response (Nishi et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2006; Charbonnier et al., 2007; Dantas et al., 2011). However, siCetn3 caused no obvious cell cycle defect in unarrested cells (Supplemental Figure S5, A and B). Finally, each of the effects of siCetn3 was reversed by overexpression of a version of mCh-Cetn3 engineered to be resistant to siCetn3 (sirCetn3; Supplemental Figure S5, C–E), suggesting that the defects in siCetn3-transfected cells are the result of depletion of endogenous Cetn3 rather than any off-target effect of siCetn3.

FIGURE 7:

Cetn3 depletion leads to formation of long, linear Cetn2 structures and mitotic abnormalities in S phase–arrested cells. (A–D) HeLa cells were prepared as described in Figure 6. (A) Representative image of long, linear Cetn2 structures in Cetn3-depleted HeLa cells; Cetn2 (green), γ-tubulin (red), α-tubulin (blue), DNA (gray). The Cetn2 linear structure is positive for α-tubulin and is adjacent to the centrosome. (B) Percentage of S phase–arrested cells with long, linear Cetn2 structures. Values represent mean ± SD of triplicate samples for which at least 75 cells were counted per replicate. (C) Representative images of Cetn3-depleted HeLa cells with abnormal mitotic spindles stained with α-tubulin, γ-tubulin, and Cetn2; left, DNA (gray), α-tubulin (blue), γ-tubulin (green), and Cetn2 (red). (D) Bar graph shows percentage of S phase–arrested cells that had the indicated mitotic structures. Values represent mean ± SD of triplicate samples, where n = 500 for each replicate. Bar, 5 μm.

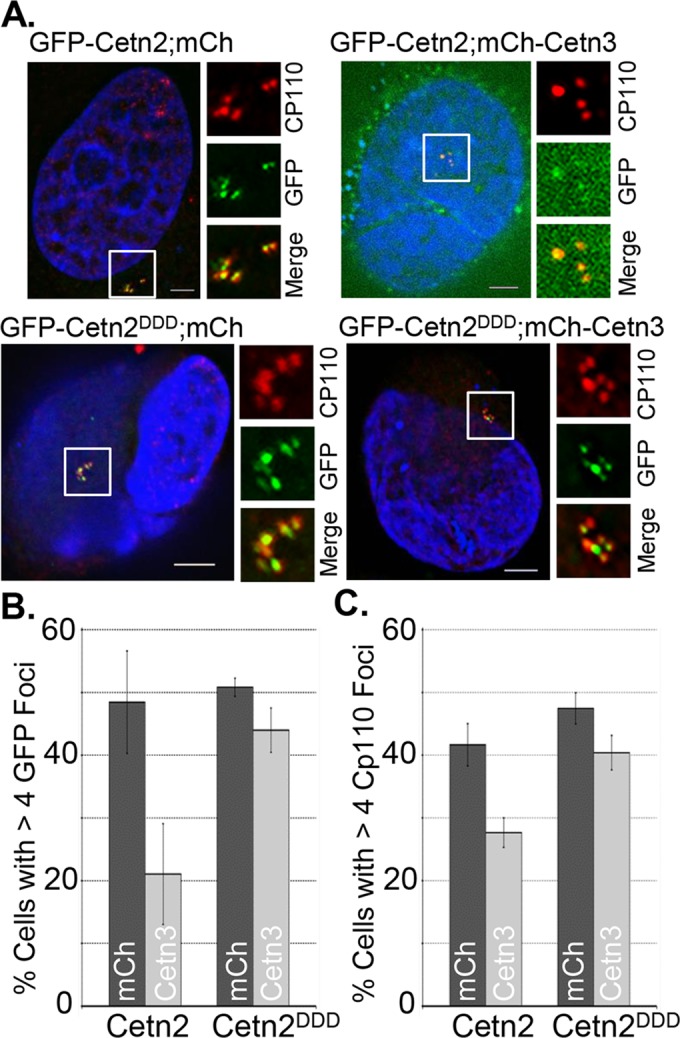

Cetn3 overexpression blocks centrosome reduplication

U2OS cells undergo centrosome reduplication after a prolonged S phase arrest. If Cetn3 inhibits Mps1 in living cells, as we have described in vitro, we might expect Cetn3 overexpression to attenuate this reduplication. Consistent with this expectation, we found that mCh-Cetn3 caused a fivefold reduction in the percentage of U2OS cells with more than two centrosomes, as determined by the number of γ-tubulin foci, suggesting that Cetn3 can suppress centrosome reduplication (Supplemental Figure S6). Given that Cetn3 prevents Mps1 from phosphorylating Cetn2 in vitro and prevents the incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles, we next sought to determine whether Cetn3 could also affect the Cetn2-dependent centriole overproduction that occurs during a prolonged S phase arrest in HeLa cells. As shown previously (Yang et al., 2010), overexpression of wild-type GFP-Cetn2 in HU-arrested HeLa cells resulted in the production of more than four GFP foci in ∼50% of cells, and mCh had no effect on this ability of Cetn2 to promote centriole overproduction (Figure 8, A and B). However, co-overexpression of mCh-Cetn3 led to a roughly twofold reduction in the percentage of GFP-Cetn2–expressing cells with greater than four Cetn2 foci, confirming the inhibitory potential of Cetn3 (Figure 8, A and B). We observed a similar reduction in the percentage of cells with more than four CP110 foci (Figure 8C), suggesting that the effects of overexpressed Cetn3 extended beyond the incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles. To test whether Cetn3 prevents Cetn2-dependent centriole reduplication by inhibiting Mps1, we assessed whether mimicking Mps1 phosphorylation of Cetn2 could bypass the inhibitory effect of Cetn3 overexpression. Mps1 phosphorylates three sites within Cetn2, T45 and T47 in EF hand 1 and T118 in EF hand 3 (Yang et al., 2010). GFP-Cetn2DDD, in which T45, T47, and T118 are all mutated to aspartic acid to mimic phosphorylation through negative charge, completely bypassed the inhibitory effect of Cetn3 (Figure 8, A–C), although mCh-Cetn3 did cause a slight reduction in the intensity of the GFP-Cetn2DDD at centrioles (Figure 8A). The observation that mimicking Mps1 phosphorylation of Cetn2 bypasses the inhibitory effects of Cetn3 overexpression supports the hypothesis that the effects of Cetn3 overexpression on centriole biogenesis might be through inhibition of Mps1, at least with respect to Cetn2-dependent centriole over duplication.

FIGURE 8.

Cetn3 overexpression blocks Cetn2-dependent centrosome reduplication in S phase–arrested cells. HeLa cells were doubly transfected with the indicated combinations of mCh or mCh-Cetn3 (Cetn3) and GFP-Cetn2 (Cetn2) or GFP-Cetn2DDD (Cetn2DDD), arrested in S phase for 48 h as described in Materials and Methods, and stained with antibodies against CP110. (A) Representative images of HeLa cells doubly transfected as indicated; DNA (blue), GFP-Cetn2 constructs (green), and CP110 (red; mCh signal not shown). Bar, 5 μm. (B, C) Bar graphs showing the percentage of S phase–arrested HeLa cells with more than four foci for (B) GFP or (C) CP110 for each double transfection. Values in B and C represent mean ± SD of triplicate samples for which at least 75 cells were counted per replicate. Mimicking phosphorylation at all three Mps1 phosphorylation sites (T45, T47, T118) bypasses the inhibitory effect of Cetn3 on both excess centriole production and incorporation of Cetn2 and CP110 into centrioles.

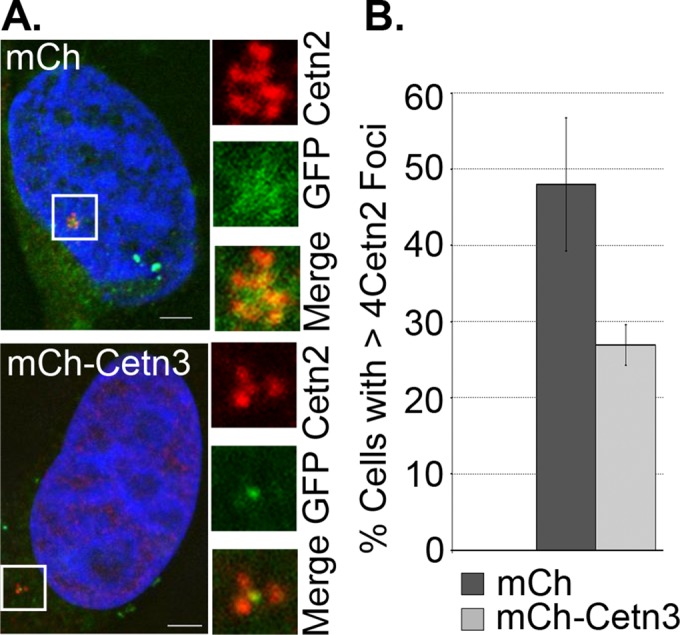

Cetn3 inhibits the Mps1∆12/13-dependent generation of excess Cetn2 foci

To assess further whether Cetn3 antagonizes Mps1 in living cells, we tested whether overexpressing Cetn3 could antagonize an Mps1-dependent event, using a previously described HeLa-derived cell line that inducibly expresses GFP-Mps1∆12/13 (Kasbek et al., 2009). Whereas overexpression of wild-type Mps1 does not cause centrosome reduplication in most human cells tested, Mps1∆12/13 (which lacks a centrosome-specific degradation signal and cannot be properly degraded at centrosomes) causes centrosome reduplication in all human cells tested (Kasbek et al., 2007, 2009), even when expressed at levels that are twofold to fivefold lower than that of endogenous Mps1, as is the case in HeLa GFP-Mps1∆12/13 cells (Kasbek et al., 2009). Whereas mCh alone had no effect on the efficiency of centrosome reduplication in HeLa GFP-Mps1∆12/13 cells, mCh-Cetn3 caused a twofold reduction in the percentage of cells with more than four Cetn2 foci (Figure 9, A and B), although it did not have any effect on the percentage of cells with excess CP110 foci (unpublished data). This suggests that overexpressed Cetn3 does not inhibit all Mps1 functions at centrosomes and is consistent with our previous findings that Mps1∆12/13 can generate excess CP110-containing structures in Cetn2-depleted cells (Yang et al., 2010). Nonetheless, because mimicking Mps1 phosphorylation within Cetn2 renders it resistant to the effect of Cetn3 overexpression (see Figure 8), these data show that overexpressed Cetn3 inhibits the Cetn2-dependent functions of centrosomal Mps1 in living cells; if Cetn3 had not inhibited Mps1∆12/13, Cetn2 would have been phosphorylated and thus resistant to Cetn3 overexpression, and the overexpressed Cetn3 would have had no effect.

FIGURE 9:

Overexpression of Cetn3 inhibits Mps1∆12/13-dependent formation of excess Cetn2 foci in S phase–arrested cells. HeLa GFP-Mps1∆12/13 cells were transfected with mCh or mCh-Cetn3, arrested in S phase for 48 h, and then stained with Cetn2 (red). (A) Representative images of mCh-positive HeLa GFP-Mps1∆12/13 cells (mCh signal not shown) showing GFP-Mps1∆12/13 (GFP, green) and Cetn2 (red). DNA is blue. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Percentage of cells with more than four Cetn2 foci. Values represent mean ± SD of triplicate samples for which at least 75 cells were counted per replicate. Overexpression of Cetn3 leads to a reduction in the number of HeLa GFP-Mps1∆12/13 cells with excess Cetn2 foci.

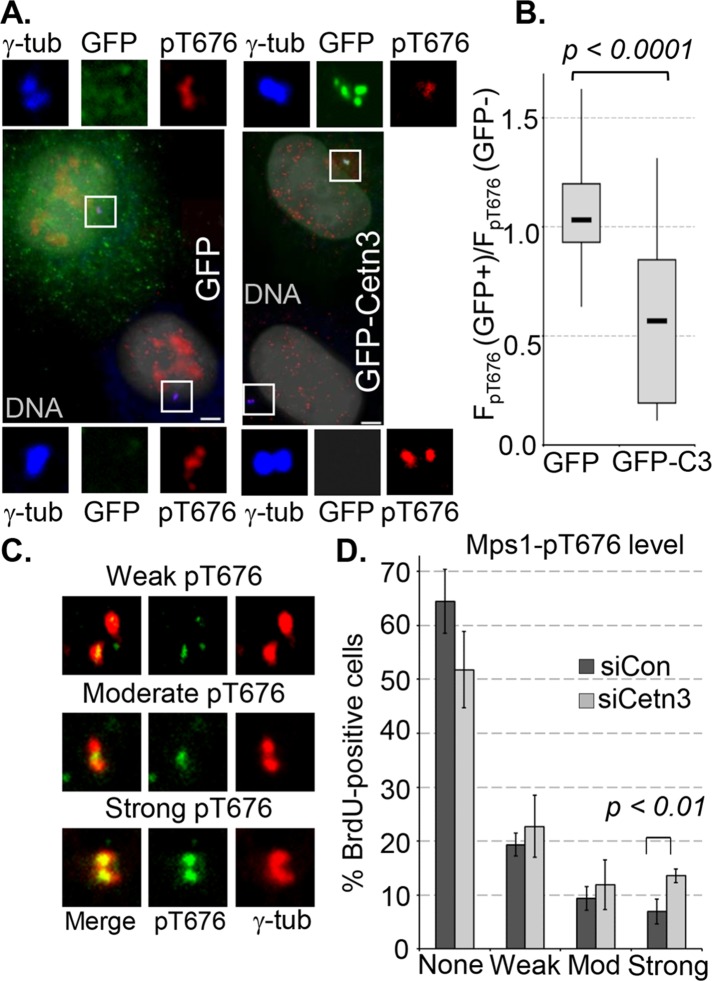

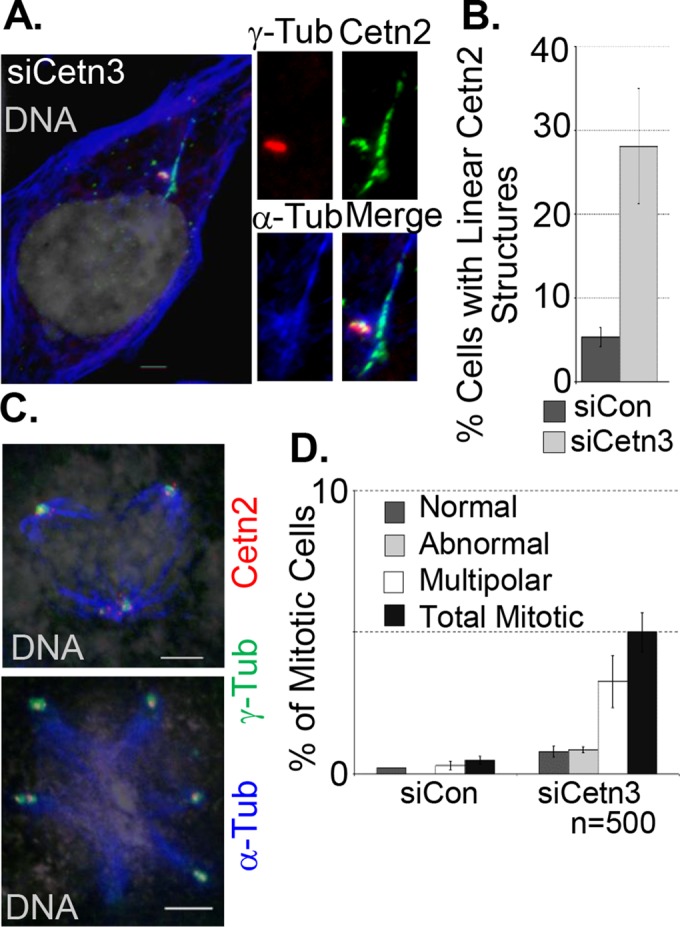

Cetn3 inhibits Mps1 activity at centrosomes

To examine directly the possibility that Cetn3 inhibits Mps1 in cells, we assessed cellular phosphorylation of Mps1 at Thr-676, which is inhibited biochemically by Cetn3 (Figure 1) and is a cellular marker for catalytically active Mps1 (Mattison et al., 2007; Tyler et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009). As previously described (Tyler et al., 2009) and recently verified (von Schubert et al., 2015), T676-phosphorylated Mps1 can be localized at centrosomal structures during mitosis (Supplemental Figure S7A). As shown in Figure 10A, T676-phosphorylated Mps1 is also found at centrosomes during interphase. HeLa cells transfected with GFP or GFP-Cetn3 were arrested in S phase with a 24-h HU treatment, and cell pairings in which one cell expressed GFP or GFP-Cetn3 and the other did not were analyzed (e.g., Figure 10A). We then determined the ratio of centrosomal pT676 (normalized to γ-tubulin; FpT676) in the GFP-positive cell to that in the untransfected cell for 25 pairs from each transfection, as previously described (Kasbek et al., 2007; Majumder and Fisk, 2014). Whereas centrosomal pT676 staining in cells expressing GFP alone was essentially the same as in untransfected cells (the median value of FpT676(GFP+)/FpT676(GFP–) was close to 1), there was a twofold reduction in centrosomal pT676 in cells expressing GFP-Cetn3 (Figure 10B), and the difference between GFP and GFP-Cetn3 was highly significant (p < 0.0001). In contrast, after siRNA knockdown of Cetn3, we observed a twofold increase in the percentage of BrdU-positive cells with strong centrosomal pT676 staining and a corresponding decrease in the percentage of cells lacking centrosomal pT676 staining (Figure 10, C and D). This does not appear to reflect a difference in Mps1 protein level at the centrosomes, because there was no statistically significant difference in the centrosomal intensity generated with a pan-Mps1 antibody between BrdU-positive control and Cetn3-depleted cells (Supplemental Figure S7, B and C). Cetn3 depletion also had no effect on whole-cell levels of Mps1 (Supplemental Figure S7D). Therefore our experiments concur that Cetn3 can inhibit Mps1 transautophosphorylation at T676 in vitro (Figure 1) and that Cetn3 overexpression inhibits T676 phosphorylation of centrosomal Mps1 in human cells. Together our overexpression, depletion, and rescue data support our hypothesis that endogenous Cetn3 antagonizes transautophosphorylation within the Mps1 catalytic domain to inhibit the ability of Mps1 to phosphorylate Cetn2, thereby attenuating aspects of centriole assembly, including the incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles.

FIGURE 10:

Cetn3 inhibits Mps1 activity in human cells. (A, B) HeLa cells were transfected with GFP or GFP-Cetn3, arrested in S phase by a 24-h HU treatment, and analyzed by quantitative IIF using antibodies against T676-phosphorylated Mps1 (pT676) and γ-tubulin (γ-tub). (A) Fields containing representative pairs of GFP-positive and adjacent untransfected (GFP–) cells used for the analysis in B, showing GFP (green), pT676 (red), γ-tubulin (blue), and DNA (gray). Bar, 5 μm. (B) The normalized level of pT676 at centrosomes, FpT676, was determined as described in Materials and Methods for both a GFP-positive (GFP+) cell and an adjacent untransfected (GFP–) cell that were imaged at the same time. The ratio FpT676(GFP+)/FpT676(GFP–) was calculated for 25 such cell pairs, and the data are presented in a box and whisker diagram. Here and in all other cases, boxes indicate lower and upper quartiles, a the marker in the box (–) indicates the median, and the whiskers represent minimum and maximum values for each series; p value was determined by unpaired t test. (C, D) Asynchronously growing HeLa cells were transfected with either control (siCon) or Cetn3-specific siRNA (siCetn3) for 68 h and then labeled with BrdU for 4 h and analyzed by IIF with Mps1 pT676 and an antibody against γ-tubulin. (C) Representative images of BrdU-positive (blue) HeLa cells with weak, moderate, and strong pT676 staining (green) at centrosomes (γ-tub, red). Bar, 5 μm. (D) Bar graph showing the percentages of BrdU-positive HeLa cells with the indicated level of centrosomal Mps1 pT676–staining bars. Values represent mean ± SD for three independent experiments, for which at least 75 cells were counted per replicate.

DISCUSSION

Cetn2 was previously shown to promote centriole overproduction in a cell type–specific manner that requires Mps1 kinase (Yang et al., 2010). The yeast centrin Cdc31p has also been shown to be phosphorylated by Mps1 to regulate SPB duplication (Araki et al., 2010), and we previously identified three sites within human Cetn2 whose phosphorylation by Mps1 promotes centriole overproduction (Yang et al., 2010). However, despite growing evidence that Cetn2 and Cetn3 are functionally distinct (Middendorp et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2010; Vonderfecht et al., 2012), a specific function for Cetn3 at the vertebrate centrosome has remained elusive. Here we expand our knowledge of Cetn3 by demonstrating that it restrains centriole assembly by inhibiting Mps1 kinase activity at centrosomes. Biochemically, Cetn3 binds to Mps1 and prevents it from phosphorylating Cetn2 in vitro but does not prevent the binding of Cetn2 to Mps1. Instead, the ability of Cetn3 to decrease Mps1 autophosphorylation generally and the transphosphorylation of the Mps1 kinase domain at pT676 specifically suggests that Cetn3 acts as a specific allosteric inhibitor of Mps1. One interesting possibility to explain the mechanism of inhibition is that Cetn3 might bind preferentially to inactive (or partially inactive) Mps1 to prevent its activation, inducing a conformational change that disrupts the dimeric interaction between an active Mps1 monomer and an inactive Mps1 monomer (Chu et al., 2008, 2010; Hewitt et al., 2010). In the cellular environment, Cetn3 might also change the susceptibility of pT676 to Mps1 phosphatases, although this would not explain our in vitro findings. Taken together, our observations that Cetn3 inhibits both a specific Mps1 autophosphorylation event and phosphorylation of both the specific substrate Cetn2 and the generic substrate MBP over a wide range of concentrations suggest that Cetn3 is an allosteric Mps1 inhibitor that regulates Mps1 autoactivation in vitro, and it will be interesting to determine whether Cetn3 or a functionally related protein regulates the activity of Mps1 in the spindle assembly checkpoint.

Of interest, Cetn3 overexpression prevents the incorporation of Cetn2 into excess centrioles in cells expressing the nondegradable Mps1∆12/13 but did not prevent Mps1∆12/13 from generating excess CP110-containing structures. Although this seemingly contradicts a role for Cetn3 as a general inhibitor of Mps1, there are several possible explanations for the apparent discrepancy. The production of excess CP110-containing structures may depend on noncatalytic functions of Mps1 that are not sensitive to Cetn3, or perhaps the twofold reduction in Mps1 activity at centrosomes caused by overexpression of Cetn3 is sufficient to inhibit Cetn2-dependent functions of Mps1 but not other centrosomal Mps1 functions. Alternatively, the interaction of Cetn3 with Mps1 may be temporally or spatially restricted so that it cannot interact with a pool of Mps1 that promotes the production of excess centrioles but can interact with a pool that drives incorporation of Cetn2 into these excess centrioles. This latter possibility is supported by the observation that Cetn3 binds to a minor form of Mps1.

Overexpression of Cetn3 also prevents accumulation of Cetn2 at newly assembled centrioles during the canonical centriole assembly cycle but does not inhibit canonical centriole biogenesis per se, as other centriole markers such as HsSAS-6 and CP110 were unaffected. Nonetheless, several observations support a role for Cetn3 in centriole assembly. First, Cetn3 depletion leads to the production of excess centrioles in S phase–arrested HeLa cells, suggesting that endogenous Cetn3 acts to restrain centriole assembly. Second, overexpression of Cetn3 blocks centrosome reduplication in U2OS cells. The observation that codepletion of Cetn2 and Cetn3 does not prevent Plk4-dependent centriole overproduction in U2OS cells (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007) contributed to the current understanding that Cetn2 is dispensable for centriole assembly. Although several subsequent studies support that conclusion (Strnad et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2010; Dantas et al., 2013), data presented here suggest that by relieving the inhibitory effect of Cetn3, codepletion of Cetn2 and Cetn3 may have masked the effect of depleting Cetn2 alone. Third, overexpressed Cetn3 blocks Cetn2-dependent centriole overproduction, which requires Mps1 activity (Yang et al., 2010). We assume that Cetn3 overexpression similarly affects centriole assembly through Mps1, because overexpressed Cetn3 caused a twofold reduction in markers of Mps1 activity at centrosomes and the inhibitory effect of Cetn3 is bypassed by mimicking phosphorylation of Mps1 sites within Cetn2.

In addition to excess centrioles, we observed long, linear structures that contained Cetn2, CP110, and microtubules but only lightly stained for γ-tubulin in a small percentage of Cetn3-depleted cells. This phenotype is reminiscent of the elongated centriole phenotype recently described in avian DT40 cells overexpressing POC5 (Dantas et al., 2013). Those POC5-dependent linear structures also contained Cetn2, and of the three avian centrins, only Cetn2 could support their assembly. We also saw abnormal mitotic cells in HU-arrested, Cetn3-depleted cells. It seems unlikely that this aberrant cell cycle progression of S phase– arrested cells is related to the elevated Mps1 activity in Cetn3-depleted cells because Mps1 activity promotes cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage (Wei et al., 2005; Yeh et al., 2009). Instead, it seems likely that Cetn3 has a role in cell-cycle regulation after HU-induced replication stress, similar to the role of Cetn2 in DNA damage control. Such a role for Cetn3 could be mechanistic, like the role of Cetn2 in DNA repair (Araki et al., 2001; Thompson et al., 2006; Klein and Nigg, 2009; Dantas et al., 2011), or regulatory, such as the recently documented role for Cetn2 in the expression of the Xenopus FGF8 and FGFR1a genes (Shi et al., 2015).

This study uses overexpression and depletion studies to further elucidate the role of Cetn3 in centrosome duplication in human cells. Overall our data suggest that Cetn3 is a biological inhibitor of Mps1 that functions at the centrosome, indirectly modulating the incorporation and function of Cetn2 by inhibiting Mps1. Our study emphasizes the notion that although the two centrin families have high sequence similarity, they are not functionally redundant and appear to play distinct roles at centrosomes. This study also highlights a model in which Cetn3 has an inhibitory effect (likely driven through inhibition of Mps1 activity) on the incorporation of Cetn2 into centrioles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HeLa S3, HEK 293, Tet-inducible HeLa GFP-Cetn2, and Tet-inducible HeLa GFP-Mps1Δ12/13 (Kasbek et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2010) cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone, Logan, UT, or Corning, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA), 100 U/ml penicillin G, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in 5% CO2. The expression of GFP-Cetn2 was induced by the addition of 1 μg/ml doxycycline (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

Plasmids

Previously described plasmids that were used for the present study are as follows: pHF64 pGEX-6P1-GST-Mps1 and pHF80 pECE-GFP-Cetn2 (Fisk et al., 2003); pHF188 pDEST17-His-Cetn2, pHF289 pDEST17-His-Cetn3, pHF251 pECE-GFP-Cetn2DDD, and pHF294 pECE-GFP-Cetn3 (Yang et al., 2010); and pHF286 pECE-GFP and pHF287 pECE-GFP-Mps1, which contain the β-globin intron (Majumder and Fisk, 2013).

Plasmids created for this study are as follows: pHF301 pECE-mCherry was created using PCR to flank the mCherry open reading frame (ORF; a kind gift of Roger Tsien, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA) with a SalI site at its 5′ end and a KpnI site at its 3′ end and cloning into the SalI and KpnI sites of pECE plasmid. pHF302 pECE-mCherry-Cetn3 was created using PCR to flank the Cetn3 ORF from pHF289 with a KpnI site at its 5′ end and a EcoRI site at its 3′ end and cloning into the KpnI and EcoRI sites of pHF301. pHF298 pECE-GFP-Mps1KD was created by cloning the β-globin intron into pHF56 pECE-GFP-Mps1KD (Fisk et al., 2003). pHF303 pECE-GFP-biotin, pHF304 pECE-GFP-biotin-Mps1, and pHF305 pECE-GFP-biotin-Mps1KD containing the β-globin intron upstream of the GFP ORF and the biotin tag 3′ of and in-frame with GFP were created by inserting a 234–base pair DNA fragment encoding a peptide that is biotinylated in vivo (Tagwerker et al., 2006; Mukherjee et al., 2014; a kind gift from Dan Schoenberg, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) into pHF286, pHF287, and pHF298 using the In-fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). pHF306 pGEX-6P1-Mps1515-794KD was created by cloning an 840–base pair DNA fragment encoding the catalytically inactive kinase domain of Mps1 from pHF56 into pGEX-6P1 vector. The sequences of primers used for PCR are available on request.

siRNA and plasmid transfection

Plasmids (1 μg each) were transfected into human HeLa or HEK 293 cells using Jetprime (Polyplus, New York, NY) or TansIT 2020 (Mirus, Madison, WI). The sequence of a previously described siRNA (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007) that binds to the junction of the Cetn3 ORF and 3′ untranslated region was used to generate a Cetn3-specific silencer select siRNA (Invitrogen). LaminA/C siRNA (Dharmacon, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) was used as a negative control. These siRNAs were transfected at a final concentration of 20 nM in HeLa cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). The efficiency of siRNA knockdown was determined by immunoblotting.

S phase arrest and BrdU/EdU incorporation assay

HeLa S3, HeLa GFP-Cetn2, or HeLa GFP-Mps1Δ12/13 cells were arrested in S phase by treatment with 4 mM HU (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 24 h after transfection, as previously described (Kasbek et al., 2007). Cells were synchronized with a 24-h HU treatment, which was considered time 0 h of S phase arrest, and then maintained in S phase arrest in the continued presence of HU for 48 h. Coverslips were fixed and processed for indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) with different centriolar markers as will be described. For S phase pulse labeling, 40 μM 5- BrdU was added to HeLa or HeLa GFP-Cetn2 cells 44 h after transfection, and BrdU incorporation and centriole number were assessed by IIF at 48 h after transfection. In some experiments, BrdU was removed after the 4-h pulse, and BrdU-labeled cells were chased for an additional 4 h in fresh medium lacking BrdU, then fixed and processed for IIF at 52 h posttransfection as previously described (Yang et al., 2010). Pulse-chase labeling with 10 μM EdU was carried out in HeLa cells using a similar procedure.

Indirect immunofluorescence

For overexpression experiments, cells were fixed with either methanol or formaldehyde and processed for IIF as described previously (Fisk and Winey, 2001; Fisk et al., 2003). For methanol fixation, cells were fixed in methanol for 10 min at −20°C, washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5 mM MgCl2 (PBS-Mg), blocked for 1 h at room temperature with blocking buffer A (3% bovine serum albumin [BSA] and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS), and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies in blocking buffer A. On the next day, the cells were washed four times in PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100), and then stained for 1 h with secondary antibodies and Hoechst 33258 in blocking buffer A at room temperature, washed four times in PBST, and mounted on slides. For formaldehyde fixation, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde prepared in PBS-Mg and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, washed four times, and then blocked in blocking buffer B (5% fetal bovine serum, 200 mM glycine, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) and stained overnight at 4°C. On the next day, the cells were washed four times for 5 min each in PBS-Mg, followed by the addition of secondary antibodies in blocking buffer B at room temperature. For transient siRNA knockdown experiments, cells were fixed with methanol and processed as described.

BrdU staining for formaldehyde-fixed cells was carried out as described previously (Yang et al., 2010). Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and washed four times with PBS-Mg. The cells were then permeabilized with freshly made 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature, washed four times with PBS-Mg, and then incubated at 37°C for 1 h with 0.4 U/μl DNaseI in PBS with 4 mM MgCl2. The coverslips were washed three times with PBS-Mg, and the procedure described for formaldehyde staining was followed using rat anti-BrdU (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and Alexa 350–conjugated anti-rat secondary antibodies.

BrdU staining of methanol fixed cells was accomplished as previously described (Majumder et al., 2012). Briefly, after incubation with primary antibodies to centrosomal proteins followed by secondary antibodies in blocking buffer A, cells were fixed again in methanol, treated with 2 N HCl for 30 min at room temperature, neutralized using 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, for 5 min, incubated with blocking buffer A for 30 min, and then stained with rat anti-BrdU and Alexa 350–conjugated donkey anti-rat antibodies.

For EdU staining, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde prepared in PBS-Mg and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, followed by blocking in blocking buffer (1% BSA in PBS) for 40 min at room temperature. The cells were incubated in EdU Click-IT solution prepared according to manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature and washed four times with 1% BSA in PBS-Mg solution, and the formaldehyde/Triton X-100 procedure for IIF described earlier was used for antibody incubations.

The primary antibodies used for IIF were as follows: mouse anti–HsSAS-6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz CA), rabbit Mps1 pT676 (Tyler et al., 2009), rabbit anti-Cetn2 (Yang et al., 2010), rabbit anti-CP110 (this study), mouse anti–γ-tubulin (GTU-88; Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti–γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), goat anti–γ-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-Cep135 (Abcam), mouse anti–acetylated tubulin (Ac-tub; Sigma-Aldrich), DM1A mouse anti–α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), pan Mps1 (H00007272-M02; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), rat anti-BrdU (Abcam), and mouse anti-GFP (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The intensity of total centrosomal Mps1 protein (pan Mps1 antibody MO2) or centrosomal Mps1 activity (phosphospecific Mps1 antibody pT676) was measured in 25 cells for each sample as previously described (Majumder et al., 2012; Majumder and Fisk, 2014). A rabbit antibody against Cetn3 was generated by injecting 6-histidine (His)-Cetn3 into rabbits (Lampire Biologicals, Pipersville, PA), and then affinity purification of serum against His-Cetn3 bound to Affigel 15 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was performed as previously described for Cetn2 (Yang et al., 2010). The CP110 antibody used here is similar to that described by Chen et al. (2002) and was generated by injecting GST fused to CP110 amino acids 1–150 into rabbits (Lampire Biologicals) and affinity purification of serum against the immunogen.

Pull-down assays, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting

HEK 293 cells were transfected with GFP-biotin, GFP-biotin-Mps1, or GFP-biotin-Mps1KD expression constructs and then arrested with 4 mM HU for 24 h and lysed in cell lysis buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1% NP-40. Pull downs were carried out using Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1 (Invitrogen). The isolated complexes were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). IRDye800-conjugated streptavidin (1:1000) was used to detect bound GFP-biotin, GFP-biotin-Mps1, or GFP-biotin-Mps1KD. Cetn2 and Cetn3 binding were verified using rabbit anti-Cetn2 (1:2000; Yang et al., 2010) and mouse anti-Cetn3 (1:1000; Novus Biologicals). Secondary antibodies were Alexa 680–conjugated donkey anti-mouse/rabbit (Invitrogen) and IRDye800-conjugated donkey anti-mouse/rabbit (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA) or horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse/rabbit at 1:10,000 dilutions (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies were detected using the LI-COR Odyssey scanner (LI-COR, Lincoln NE) as previously described (Majumder et al., 2012) or by using SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Endogenous Cetn3 or Mps1 were immunoprecipitated using rabbit anti-Cetn3 (this study) or rabbit anti-Mps1 MDS (Kasbek et al., 2009) from HU-arrested HeLa or HEK 293 cells. Lysates were first precleared by the addition of protein G beads to remove proteins that nonspecifically bound to beads. Antibodies were then bound to fresh protein G beads, which were added to the precleared lysates. Immune complexes were precipitated, washed four times in lysis buffer, and then subjected to SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Coimmunoprecipitation of Mps1, Cetn2, or Cetn3 was revealed by immunoblotting with mouse anti-Mps1 N1 (Invitrogen), rabbit anti-Cetn2 (Yang et al., 2010, or Biolegend, San Diego, CA) or mouse anti-Cetn3 (Novus Biologicals) antibodies.

Kinase assays

Kinase assays with bacterially expressed recombinant proteins were performed as described previously (Kasbek et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2010) using 1 μg of His-Cetn2, 1 μg of GST-Mps1KDD, 0.1 μg of GST-Mps1, and various amounts of His-Cetn3. The concentration of the proteins was estimated by Sypro Ruby staining of an SDS–PAGE gel and comparison of band intensity to known amounts of BSA or lysozyme protein standards. Kinase assay samples containing 10 μM ATP and 10 μCi of [γ32P]ATP (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) were assembled in a 1× kinase assay buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (Fisher Scientific), 1× protease inhibitor (Invitrogen), 2 μM AEBSF-HCl (Invitrogen), and 10 mM MgCl2 and incubated for a total time of 1 h at 30°C, then analyzed by SDS–PAGE, followed by autoradiography of dried Coomassie-stained gels. In specified experiments, Mps1 was preincubated with Cetn2 or Cetn3 for 30 min before addition of additional centrin proteins for a further 30 min. In nonradioactive experiments, kinase assays using 2 mM ATP were preformed, and samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using pT675, pT676, or pT686 rabbit antibodies.

In vitro binding assay

GST or GST-Mps1 bound to glutathione Sepharose beads as bait protein was incubated with 0.05 μg of recombinant His-Cetn2 and/or 0.06 μg of recombinant His-Cetn3 (which was precleared using glutathione beads) in kinase assay buffer in the presence or absence of 2 mM ATP and the presence or absence of 5 mM MgCl2 or 2 mM CaCl2 for 1 h at 30°C. The proteins were then incubated at room temperature for 2 h on a shaking platform. After recovery of the beads, bound proteins were extracted with 2× SDS–PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Serial-section electron microscopy

HeLa cells were plated onto four-well Lab-Tek chamber slides (Fisher Scientific), transfected with either siLamin A/C (control siRNA) or siCetn3, and arrested in S phase for 48 h as described. Cells in the chamber slides were fixed overnight at 4 ºC in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). After fixation, cells were processed at the Ohio State University Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility as previously described (Yang et al., 2010).

In-cell Western procedure

HeLa cells were transfected with different plasmids and then plated onto a 96-well dish. After a 48-h S phase arrest, cells were fixed in fixing solution containing 3.7% formaldehyde and 0.2% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were washed four times with PBS-Mg, blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer (LI-COR) for 1.5 h, incubated for 1 h with primary antibodies diluted in Odyssey blocking buffer or blocking buffer alone (to correct for background staining), washed four times with PBS-Mg, and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature in secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. After removal of secondary antibodies, cells were washed four times in PBS-Mg, and the 96-well dish was then imaged on the LI-COR Odyssey scanner. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-Cetn3 (Novus Biologicals) and rabbit anti–γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich). Secondary antibodies were Alexa 680–conjugated donkey anti-mouse/rabbit and IRDye800-conjugated donkey anti-mouse/rabbit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Matthew Nienkirchen for his work on production of the CP110 antibody and for affinity purification of rabbit anti-Cetn2. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM077311 to H.A.F. and a Mirus Bio Research Award to D.S. In addition, S.M. was partially supported by an Up on the Roof Fellowship from the Human Cancer Genetics Program of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Abbreviations used:

- BrdU

5-bromodeoxyuridine

- Cetn2

centrin 2

- Cetn3

centrin 3

- HU

hydroxyurea

- mCh

mCherry.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1248) on September 9, 2015.

REFERENCES

- Araki Y, Gombos L, Migueleti SPS, Sivashanmugam L, Antony C, Schiebel E. N-terminal regions of Mps1 kinase determine functional bifurcation. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:41–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki M, Masutani C, Takemura M, Uchida A, Sugasawa K, Kondoh J, Ohkuma Y, Hanaoka F. Centrosome protein centrin 2/caltractin 1 is part of the xeroderma pigmentosum group C complex that initiates global genome nucleotide excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18665–18672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimzadeh J, Marshall WF. Building the centriole. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R816–R825. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron AT, Greenwood TM, Bazinet CW, Salisbury JL. Centrin is a component of the pericentriolar lattice. Biol Cell. 1992;76:383–388. doi: 10.1016/0248-4900(92)90442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum P, Furlong C, Byers B. Yeast gene required for spindle pole body duplication: homology of its product with Ca2+-binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:5512–5516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.15.5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros R, Mondesert O, Lorenzo C, Astuti P, McArthur G, Chircop M, Ducommun B, Gabrielli B. CDC25B overexpression stabilises centrin 2 and promotes the formation of excess centriolar foci. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnier J-B, Renaud E, Miron S, Le Du MH, Blouquit Y, Duchambon P, Christova P, Shosheva A, Rose T, Angulo JF, Craescu CT. Structural, thermodynamic, and cellular characterization of human centrin 2 interaction with xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:1032–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Indjeian VB, McManus M, Wang L, Dynlacht BD. CP110, a cell cycle-dependent CDK substrate, regulates centrosome duplication in human cells. Dev Cell. 2002;3:339–350. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu ML, Chavas LM, Douglas KT, Eyers PA, Tabernero L. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the mitotic checkpoint kinase Mps1 in complex with SP600125. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21495–21500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu MLH, Lang Z, Chavas LMG, Neres J, Fedorova OS, Tabernero L, Cherry M, Williams DH, Douglas KT, Eyers PA. Biophysical and X-ray crystallographic analysis of Mps1 kinase inhibitor complexes. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1689–1701. doi: 10.1021/bi901970c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JA, Tirone F, Durussel I, Firanescu C, Blouquit Y, Duchambon P, Craescu CT. Calcium and magnesium binding to human centrin 3 and interaction with target peptides. Biochemistry. 2005;44:840–850. doi: 10.1021/bi048294e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas TJ, Daly OM, Conroy PC, Tomas M, Wang Y, Lalor P, Dockery P, Ferrando-May E, Morrison CG. Calcium-binding capacity of centrin2 is required for linear POC5 assembly but not for nucleotide excision repair. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas TJ, Wang Y, Lalor P, Dockery P, Morrison CG. Defective nucleotide excision repair with normal centrosome structures and functions in the absence of all vertebrate centrins. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:307–318. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errabolu R, Sanders MA, Salisbury JL. Cloning of a cDNA encoding human centrin, an EF-hand protein of centrosomes and mitotic spindle poles. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:9–16. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk HA, Mattison CP, Winey M. Human Mps1 protein kinase is required for centrosome duplication and normal mitotic progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14875–14880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434156100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk HA, Winey M. The mouse mps1p-like kinase regulates centrosome duplication. Cell. 2001;106:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavet O, Alvarez C, Gaspar P, Bornens M. Centrin4p, a novel mammalian centrin specifically expressed in ciliated cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1818–1834. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart PE, Glantz JN, Orth JD, Poynter GM, Salisbury JL. Testis-specific murine centrin, Cetn1: genomic characterization and evidence for retroposition of a gene encoding a centrosome protein. Genomics. 1999;60:111–120. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt L, Tighe A, Santaguida S, White AM, Jones CD, Musacchio A, Green S, Taylor SS. Sustained Mps1 activity is required in mitosis to recruit O-Mad2 to the Mad1-C-Mad2 core complex. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:25–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges ME, Scheumann N, Wickstead B, Langdale JA, Gull K. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of the centriole from protein components. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1407–1413. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Cleveland DW. Boveri revisited: chromosomal instability, aneuploidy and tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:478–487. doi: 10.1038/nrm2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Mengersen A, Lee VD. Molecular cloning of cDNA for caltractin, a basal body-associated Ca2+-binding protein: homology in its protein sequence with calmodulin and the yeast CDC31 gene product. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:133–140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerka-Dziadosz M, Koll F, Włoga D, Gogendeau D, Garreau de Loubresse N, Ruiz F, Fabczak S, Beisson J. A centrin3-dependent, transient, appendage of the mother basal body guides the positioning of the daughter basal body in paramecium. Protist. 2013;164:352–368. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasbek C, Yang CH, Fisk HA. Mps1 as a link between centrosomes and genomic instability. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50:654–665. doi: 10.1002/em.20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasbek C, Yang C-H, Yusof AM, Chapman HM, Winey M, Fisk HA. Preventing the degradation of mps1 at centrosomes is sufficient to cause centrosome reduplication in human cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4457–4469. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein UR, Nigg EA. SUMO-dependent regulation of centrin-2. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3312–3321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Habedanck R, Stierhof Y-D, Nigg EA. Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev Cell. 2007;13:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingle WL. Centrosome hypertrophy in human breast tumors: Implications for genomic stability and cell polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2950–2955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz KB, Greenwood TM, Negron VC, Bruzek AK, Salisbury JL, Lingle WL. Control of centrin stability by Aurora A. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz W, Lingle WL, McCormick D, Greenwood TM, Salisbury JL. Phosphorylation of centrin during the cell cycle and its role in centriole separation preceding centrosome duplication. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20774–20780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S, Fisk HA. VDAC3 and Mps1 negatively regulate ciliogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:849–858. doi: 10.4161/cc.23824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S, Fisk HA. Quantitative immunofluorescence assay to measure the variation in protein levels at centrosomes. J Vis Exp 94, doi: 10.3791/52030. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Majumder S, Slabodnick M, Pike A, Marquardt J, Fisk HA. VDAC3 regulates centriole assembly by targeting Mps1 to centrosomes. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:3666–3678. doi: 10.4161/cc.21927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison CP, Old WM, Steiner E, Huneycutt BJ, Resing KA, Ahn NG, Winey M. Mps1 activation loop autophosphorylation enhances kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30553–30561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middendorp S, Küntziger T, Abraham Y, Holmes S, Bordes N, Paintrand M, Paoletti A, Bornens M. A role for centrin 3 in centrosome reproduction. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:405–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middendorp S, Paoletti A, Schiebel E, Bornens M. Identification of a new mammalian centrin gene, more closely related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC31 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9141–9146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee C, Bakthavachalu B, Schoenberg DR. The cytoplasmic capping complex assembles on adapter protein Nck1 bound to the proline-rich C-terminus of mammalian capping enzyme. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1001933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi R, Okuda Y, Watanabe E, Mori T, Iwai S, Masutani C, Sugasawa K, Hanaoka F. Centrin 2 stimulates nucleotide excision repair by interacting with xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5664–5674. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5664-5674.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Shimizu T. cDNA sequence for mouse caltractin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1216:126–128. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90048-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti A, Moudjou M, Paintrand M, Salisbury J, Bornens M. Most of centrin in animal cells is not centrosome-associated and centrosomal centrin is confined to the distal lumen of centrioles. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:3089–3102. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.13.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser SL, Morrison CG. Centrin2 regulates CP110 removal in primary cilium formation. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:693–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201411070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury JL, Baron A, Surek B, Melkonian M. Striated flagellar roots: isolation and partial characterization of a calcium-modulated contractile organelle. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:962–970. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury JL, Suino KM, Busby R, Springett M. Centrin-2 is required for centriole duplication in mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1287–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Zhao Y, Vonderfecht T, Winey M, Klymkowsky MW. Centrin-2 (Cetn2) mediated regulation of FGF/FGFR gene expression in Xenopus. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10283. doi: 10.1038/srep10283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang A, Courtney I, Fackler U, Matzner M, Schiebel E. The calcium-binding protein cell division cycle 31 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a component of the half bridge of the spindle pole body. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:405–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strnad P, Leidel S, Vinogradova T, Euteneuer U, Khodjakov A, Gonczy P. Regulated HsSAS-6 levels ensure formation of a single procentriole per centriole during the centrosome duplication cycle. Dev Cell. 2007;13:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagwerker C, Flick K, Cui M, Guerrero C, Dou Y, Auer B, Baldi P, Huang L, Kaiser P. A tandem affinity tag for two-step purification under fully denaturing conditions: application in ubiquitin profiling and protein complex identification combined with in vivocross-linking. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:737–748. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500368-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JR, Ryan ZC, Salisbury JL, Kumar R. The structure of the human centrin 2-xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18746–18752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RK, Chu MLH, Johnson H, McKenzie EA, Gaskell SJ, Eyers PA. Phosphoregulation of human Mps1 kinase. Biochem J. 2009;417:173–181. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonderfecht T, Cookson MW, Giddings TH, Clarissa C, Winey M. The two human centrin homologues have similar but distinct functions at Tetrahymena basal bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:4766–4777. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-06-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]