Abstract

Background

Post-operative apnea is a complication in young infants. Awake-regional anesthesia (RA) may reduce the risk; however the evidence is weak. The General Anesthesia compared to Spinal anesthesia (GAS) study is a randomized, controlled, trial designed to assess the influence of general anesthesia (GA) on neurodevelopment. A secondary aim is to compare rates of apnea after anesthesia.

Methods

Infants ≤ 60 weeks postmenstrual age scheduled for inguinal herniorraphy were randomized to RA or GA. Exclusion criteria included risk factors for adverse neurodevelopmental outcome and infants born < 26 weeks’ gestation. The primary outcome of this analysis was any observed apnea up to 12 hours post-operatively. Apnea assessment was unblinded.

Results

363 patients were assigned to RA and 359 to GA. Overall the incidence of apnea (0 to 12 hours) was similar between arms (3% in RA and 4% in GA arms, Odds Ratio (OR) 0.63, 95% Confidence Intervals (CI): 0.31 to 1.30, P=0.2133), however the incidence of early apnea (0 to 30 minutes) was lower in the RA arm (1% versus 3%, OR 0.20, 95%CI: 0.05 to 0.91, P=0.0367). The incidence of late apnea (30 minutes to 12 hours) was 2% in both RA and GA arms (OR 1.17, 95%CI: 0.41 to 3.33, P=0.7688). The strongest predictor of apnea was prematurity (OR 21.87, 95% CI 4.38 to 109.24) and 96% of infants with apnea were premature.

Conclusions

RA in infants undergoing inguinal herniorraphy reduces apnea in the early post-operative period. Cardio-respiratory monitoring should be used for all ex-premature infants.

Introduction

Post-operative apnea is a complication in young infants; the risk being greater in neonates who were premature.1–3 Reducing the risk of apnea and identifying infants at risk of apnea may reduce morbidity and guide clinicians on the optimal age for surgery and the length and intensity of post-operative observation. Spinal anesthesia is one technique that may reduce the risk of apnea. Three small trials comparing spinal and general anesthesia (GA) have reported a reduced risk of apnea in high risk infants receiving spinal anesthesia.1,4,5 These studies are difficult to interpret due to small numbers, different ways of defining and identifying apnea and different GA agents used.6 A 2003 Cochrane review called for a large well-designed randomized trial to address this issue.7

The General Anesthesia compared to Spinal anesthesia (GAS) study: comparing apnea and neurodevelopmental outcomes, is a prospective randomized trial where 722 infants undergoing inguinal herniorraphy were randomized to regional anesthesia (RA) or GA. The trial was designed primarily to address the long-term effect of GA on the developing brain with the primary outcome being neurodevelopmental outcome at five years. An important secondary aim of the GAS study is to compare the immediate post-operative benefits of RA compared to GA, in particular, reduction in apnea. This paper compares the incidence of apnea in each group and identifies other factors associated with apnea; specifically we hypothesized that RA would reduce the risk of apnea. Other short term outcomes in each group are also described.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

In a multinational prospective randomized trial with two parallel arms, we enrolled patients in seven countries and 28 sites (table 1). Institutional review board or human research ethics committee approval was obtained for each site and written informed consent obtained from parents or guardians. Eligibility criteria included infants up to 60 weeks’ postmenstrual age (PMA) scheduled for unilateral or bilateral inguinal herniorraphy (with or without circumcision) born at greater than 26 weeks’ gestation. Exclusion criteria included any contraindication for either anesthetic technique, a history of congenital heart disease requiring surgery or pharmacotherapy, mechanical ventilation immediately prior to surgery, known chromosomal abnormalities or other known acquired or congenital abnormalities which might affect neurodevelopment, previous exposure to volatile GA or benzodiazepines as a neonate or in the third trimester in utero, any known neurologic injury such as cystic peri-ventricular leukomalacia or grade three or four intra-ventricular hemorrhage, any social or geographic factor that may make follow up difficult, or having a primary language at home where neurodevelopmental tests are not available. Eligible infants were identified from operating room schedules or at pre-admission clinics and recruited in the clinic or in the preadmission areas of the operating floor.

Table 1.

Randomization by site

| Country | Site | Allocated to RA | Allocated to GA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | |||

| Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne | 57 | 58 | |

| Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne * | 26 | 25 | |

| Princess Margaret Hospital for Children, Perth | 16 | 15 | |

| Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide | 6 | 5 | |

| Italy | |||

| Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa | 42 | 39 | |

| Ospedale Vittore Buzzi, Milan | 25 | 23 | |

| Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo | 18 | 20 | |

| United States | |||

| Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston | 29 | 31 | |

| Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle | 11 | 14 | |

| Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver | 9 | 9 | |

| University of Iowa Hospital, Iowa | 8 | 8 | |

| Children’s Medical Center, Dallas | 7 | 7 | |

| Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago | 2 | 3 | |

| Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon | 2 | 2 | |

| Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville | 1 | 2 | |

| Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia | 1 | 1 | |

| The University of Vermont/Fletcher Allen Health Care, Burlington | 1 | 0 | |

| United Kingdom | |||

| Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow | 27 | 25 | |

| Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham | 7 | 6 | |

| Sheffield Children’s Hospital, Sheffield | 5 | 4 | |

| Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol | 2 | 2 | |

| Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, Belfast | 2 | 2 | |

| Royal Liverpool Children’s Hospital Alder Hey, Liverpool | 1 | 1 | |

| Canada | |||

| Montreal Children’s Hospital, Quebec | 21 | 21 | |

| CHU Sainte-Justine, Quebec | 3 | 5 | |

| The Netherlands | |||

| Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht | 15 | 14 | |

| University Medical Center Groningen | 6 | 5 | |

| New Zealand | |||

| Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland | 13 | 12 |

Including Casey hospital

GA = General Anesthesia; RA = Regional Anesthesia.

The GAS study is registered in Australia and New Zealand at ANZCTR: ID# ACTRN12606000441516 first registered on 16th October 2006, Principal Investigators Andrew Davidson, Mary Ellen McCann and Neil Morton; in the United States at ClinicalTrials.gov: ID#: NCT00756600 first registered on 18th September 2008, Principal Investigators Andrew Davidson, Mary Ellen McCann and Neil Morton; and in the United Kingdom at UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) ID#: 6635 (ISRCTN ID#: 12437565; MREC No: 07/S0709/20) Principal Investigator Neil Morton. The protocol for the GAS study has been previously published by The Lancet.8

Randomization and blinding

A 24-hour web-based randomization service was managed by The Data Management & Analysis Centre, Department of Public Health, University of Adelaide, South Australia. Children were randomized with a 1:1 allocation ratio to either RA or GA. Randomization was in random permuted blocks of two or four and stratified by site and gestational age at birth: 26 to 29 weeks and 6 days, 30 to 36 weeks and 6 days, and 37 weeks and more. The anesthesiologist, surgeon and nurses in the post-operative care units were aware of group allocation, therefore the study was unblinded for type of anesthetic given.

Procedures

The RA arm received regional nerve blocks: either spinal alone, spinal with caudal, spinal with ilioinguinal, or caudal alone. The local anesthetic used was bupivacaine or levobupivacaine. In addition, some patients received caudal chloroprocaine intra-operatively to prolong the block. The type of regional technique and the local anesthetic used were at the discretion of the anesthesiologist. In the RA arm all forms of sedation or GA were avoided if possible; however if any sedation or GA was required this was regarded as a protocol violation. Oral sucrose drops were permitted in the RA arm and paracetamol in both arms. The GA arm received sevoflurane for induction and maintenance in an air/oxygen mixture along with nerve blockade with caudal or ilioinguinal bupivacaine or levobupivacaine. The form of airway support and use of neuromuscular blocking agents was at the discretion of the anesthesiologist. No opioids or nitrous oxide were allowed intra-operatively. Blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation and temperature were recorded every 5 minutes intra-operatively.

Post-operatively children were observed closely and constantly by the research assistant for at least the first hour, or until discharge home if discharged before one hour. The research assistant was a nurse, scientist or physician. All were trained to detect apnea and familiar with the definition of a significant apnea. Electronic monitoring, and the alarm settings on monitors were not standardised. During this period any apnea was noted. Respiratory support and oxygen saturation were also recorded every five minutes. After the first hour children were observed as per the usual routine at each hospital. The level of observation and monitoring was not standardised beyond the first hour. Hospital records were reviewed to identify apnea events. The management and significance of any apnea during this period was determined from the hospital record. Hemoglobin was measured either pre-operatively or during anesthesia. Intra-operative end tidal carbon dioxide is not reported as it is not an accurate measure of arterial carbon dioxide in the presence of large leaks around the tracheal tube or face mask.

The pre-specified primary outcome for this analysis was observed apnea within 12 hours of surgery or until discharge. Apnea was defined as a pause in breathing >15 seconds or a pause >10 seconds if associated with oxygen saturation <80% or bradycardia (20% fall in heart rate). Early apnea was defined a-priori as an apnea occurring within the first 30 minutes postoperatively in the post anesthesia care unit, and late apnea was defined as an observed apnea occurring between 30 minutes and 12 hours post-operatively. A post hoc sensitivity analysis was also performed describing late apnea where children were excluded if discharged before 12 hours. Level of intervention for post-operative apnea, methyl-xanthine administration and other respiratory complications were also noted. A significant intervention was defined a-priori as any intervention greater than simple tactile stimulation and included providing oxygen by mask (with or without positive pressure ventilation), or cardiopulmonary resuscitation with external chest compressions.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size considerations

The sample size for the GAS study was based on the five year neurodevelopmental outcome; the five year follow up Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence – Third Edition full scale Intelligence Quotient score, a standardized score with mean 100 and standard deviation 15. Assuming an expected difference of one standardized score point, and a 90% chance that a 95% confidence interval will exclude a difference of more than five (the largest difference acceptable to demonstrate equivalence), the trial needed 598 infants in total. Enrolling approximately 720 allowed for 10% loss to follow-up and 10% with a major protocol violation.

Given that this paper presents data on a secondary aim of the trial, an a priori power calculation was not conducted for these secondary outcomes. In line with CONSORT recommendations we do not believe post-hoc power calculations are useful and instead we present our results along with confidence intervals, which capture the uncertainty in our findings that reflect the sample size. During recruitment a Data Monitoring Committee met at planned six month intervals. Summary data by allocation were presented to the Data Monitoring Committee and no formal group comparisons were performed.

Analysis populations

The primary analysis for apnea included participants as randomized, excluding participants who withdrew consent or were randomized after surgery. Although the future neurodevelopmental outcomes are to be based on an equivalence design the apnea data are analyzed as a superiority design. This analysis is reported as intention to treat (ITT). A secondary analysis was performed as per-protocol (APP), which excludes cases where surgery was cancelled, and in the RA arm, any child who received any sevoflurane or sedative medication.

Partial GA/sedation is defined as those in the RA group that received sevoflurane for only some of the surgery or received some other sedative medication during surgery Full GA is defined as receiving sevoflurane from prior to knife to skin to the end of surgery.

Data analysis

The unit of analysis is the participant. Apnea outcomes were analyzed if a participant is recorded as having at least one event. Categorical data are summarized using counts and percentages, and continuous data using means (standard deviation (SD)) or medians (interquartile range). For binary outcomes, a comparison between arms is presented as an Odds Ratio (OR) as estimated from a logistic regression model. For continuous outcomes, a comparison between arms is presented as a difference in means as estimated from a linear regression model. The distribution of continuous outcomes was examined for normality, and log-transformations were applied where appropriate. All estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals and two-sided p-values. Any missing data were not explored because the percentage of missing data was <5% for all outcomes. Descriptive analyzes were performed on pre-specified sub-groups. All outcomes were adjusted for i) stratified gestational age at birth as a fixed effect and ii) site of randomization using the generalized estimating equation approach with robust standard errors.9,10 Sites with less than 20 randomized infants were combined as a single site in the model. An exchangeable correlation structure was assumed between any two children from the same site. The early and late apnea outcomes were modelled together by including an additional fixed time effect (early or late time) and a fixed interaction between time and study arm. Because the generalized estimating equation approach only allows for one level of clustering, we tested two different exchangeable correlation structures for this model i) firstly we accounted for the correlation between two apnea outcomes taken from the same child, and ii) secondly between outcomes from any two children from the same site. Since almost no difference was observed in the results from the two correlation structures we show results from the second approach, so that the same correlation structure is used for all presented analyses. We judged that the interaction term provided sufficient evidence (p=0.03 for ITT analysis and p=0.09 for APP analysis) to present the effect of the study arm separately for early and late apnea, given the study was not powered to make this comparison.

Predictors of apnea were identified by constructing a logistic regression model adjusted for site of randomization using the generalized estimating equation approach as described above (Paragraph title: Data Analysis, Page 17, Paragraph 1, Line 11) and including allocated study arm as a covariate. An interaction between time and covariate was included for the combined analysis of the early and late apnea outcomes.

When presenting these results to peers we have been specifically asked for the risk reduction between RA and GA for term and ex premature infants; thus we also present a post-hoc analysis calculating the absolute risk reduction in term and ex premature infants (<37 weeks gestational age at birth).

The association between early and late apnea was assessed by constructing a logistic regression model adjusted for site of randomization using the generalized estimating equation approach as described above and including allocated study arm and stratified gestational age at birth as covariates. All analyses were carried out in Stata 13 (Stata Corp LP., College Station, TX).

Results

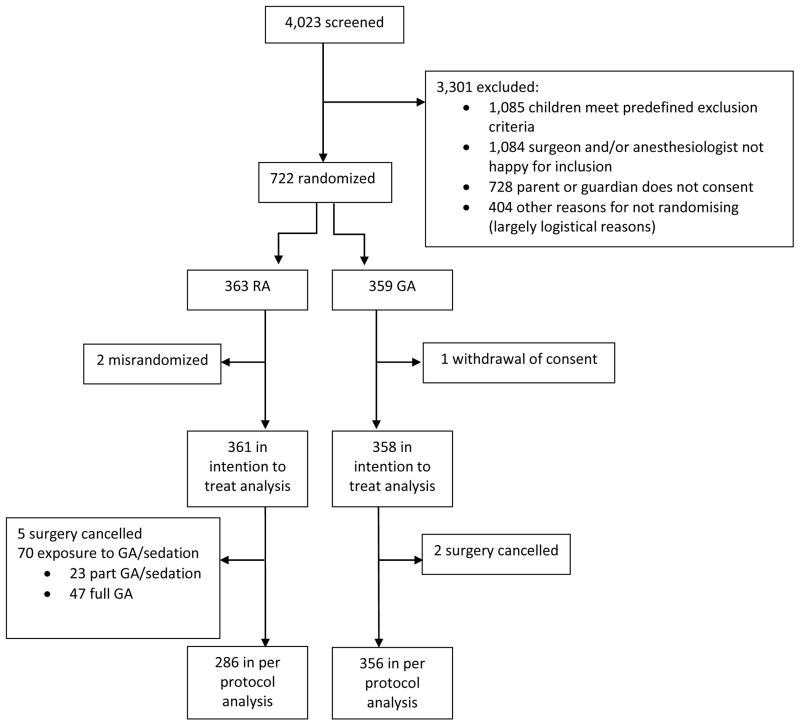

722 infants were recruited into the trial between 9th February 2007 and 31st January 2013. Three were withdrawn from analysis. For the ITT analysis 361 were in the RA arm and 358 in the GA arm (figure 1). Baseline, demographic, anesthetic and surgical data are summarized in table 2. There were 394 premature infants and 325 term infants. Outcome data is missing for five RA cases and two GA cases because surgery was cancelled, and one RA case because no data was collected. In the RA arm 70 had a protocol violation involving exposure to sevoflurane or sedation. Thus for the APP analysis 286 were in the RA arm and 356 in the GA arm (RA=355, GA=356 in the ITT analysis).

Figure 1. Consort Flow Diagram.

Of the 70 protocol violations in the RA arm, 10 infants had a full GA with no awake-regional attempted, 37 had a full general anaesthetic after complete block failure, and 23 infants had a partly successful block requiring a short period of general anaesthesia or sedation. Participants who withdrew consent (n=1) or were randomised after surgery (n=2) were excluded from intention to treat analyses. GA= General Anesthesia; RA = Regional Anesthesia.

Table 2.

Baseline, demographic, anesthetic and surgical data

| Demographics | RA arm as intention to treat N=361 |

GA arm as intention to treat N=358 |

RA arm as per protocol N=286 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 294 (82%) | 306 (85%) | 231 (81%) |

| Mean (SD) Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 35.5 (4.1) | 35.5 (3.9) | 35.5 (4.1) |

| Premature (born <37 weeks gestation) | 198 (55%) | 196 (55%) | 160 (56%) |

| Mean (SD) Chronological age at surgery (weeks) | 10.0 (4.5) | 10.1 (4.5) | 9.8 (4.4) |

| Mean (SD) Post menstrual age at surgery (weeks) | 45.5 (4.7) | 45.6 (4.6) | 45.3 (4.6) |

| Birth weight (kg) | 2.4 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.9) |

| Mean (SD) Weight at time of surgery (kg) | 4.2 (1.1) | 4.3 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.1) |

| Median Apgar at 1 minute | 9 (7 to 9) | 9 (7 to 9) | 9 (7 to 9) |

| Median Apgar at 5 minutes | 9 (9 to 10) | 9 (9 to 10) | 9 (9 to 10) |

| One of multiple pregnancy | 62 (17%) | 62 (17%) | 52 (18%) |

| Child ever discharged from hospital | 332 (93%) | 336 (94%) | 266 (93%) |

| Smoker in the household | 104 (29%) | 115 (32%) | 83 (29%) |

| Ever treated with CPAP | 91 (25%) | 90 (25%) | 70 (24%) |

| Ever treated with a methyl xanthine | 60 (17%) | 54 (15%) | 49 (17%) |

| Ever ventilated with a tracheal tube | 47 (13%) | 45 (13%) | 37 (13%) |

| Ever required supplemental oxygen (apart from at birth) | 95 (26%) | 81 (23%) | 76 (27%) |

| Supplemental oxygen immediately prior to surgery | 6 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 4 (1%) |

| Electronic monitoring for apnea in previous 24 hrs | 17 (5%) | 17 (5%) | 13 (5%) |

| Observed apnea previous 24 hrs | 6 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 6 (2%) |

| Mean (SD) Fasting time (mins) | 368.2 (146.4) | 367.3 (155.1) | 370.7 (152.6) |

| Pre-operative intravenous fluid | 46 (13%) | 45 (13%) | 36 (13%) |

| Mean (SD) Haemoglobin (g/100ml) | 10.3 (2.1) | 10.2 (2.0) | 10.3 (2.0) |

| Median (IQR) Baseline oxygen saturation | 99 (98 to 100) | 99 (98 to 100) | 99 (98 to 100) |

| Mean (SD) Baseline heart rate | 152.4 (19.7) | 149.9 (16.3) | 153.4 (19.9) |

| Surgical details | |||

| Bilateral hernia exploration/repair | 162 (46%) | 161 (45%) | 127 (44%) |

| Anesthesia details | |||

| Suxamethonium given | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Non depolarising neuromuscular blocker given | 20 (6%) | 125 (35%) | 0 |

| Spinal without caudal * | 222 (64%) | 0 | 193 (67%) |

| Caudal without spinal * | 7 (2%) | 332 (93%) | 4 (1%) |

| Caudal plus spinal * | 117 (34%) | 0 | 89 (31%) |

| Ilioinguinal block | 3 (1%) | 16 (4%) | 2 (1%) |

| Field bock | 51 (14%) | 40 (11%) | 36 (13%) |

| Laryngeal mask airway used | 7 (2%) | 60 (17%) | 0 |

| Tracheal tube used | 40 (11%) | 281 (79%) | 0 |

| Details of monitoring for apnea for All of the first 30 minutes post-operatively | |||

| Pulse oximetry | 319 (90%) | 314 (88%) | 254 (82%) |

| ECG | 124 (35%) | 111 (31%) | 89 (31%) |

| Respiratory rate monitor | 123 (35%) | 128 (36%) | 91 (32%) |

| Pneumograph | 6 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 4 (1%) |

CPAP = Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; GA = General Anesthesia; Hrs = Hours; IQR = Interquartile Range; KG = Kilograms, Mins = Minutes; RA = Regional Anesthesia; SD = Standard Deviation.

Data presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range or frequencies and percentage of non missing data.

Note these data refer to all cases where the listed blocks were attempted prior to start of surgery whether the blocks were effective or not. GA as-per-protocol data are not presented as only 2 children in the GA arm had surgery cancelled so the data are very similar to the intention-to-treat data

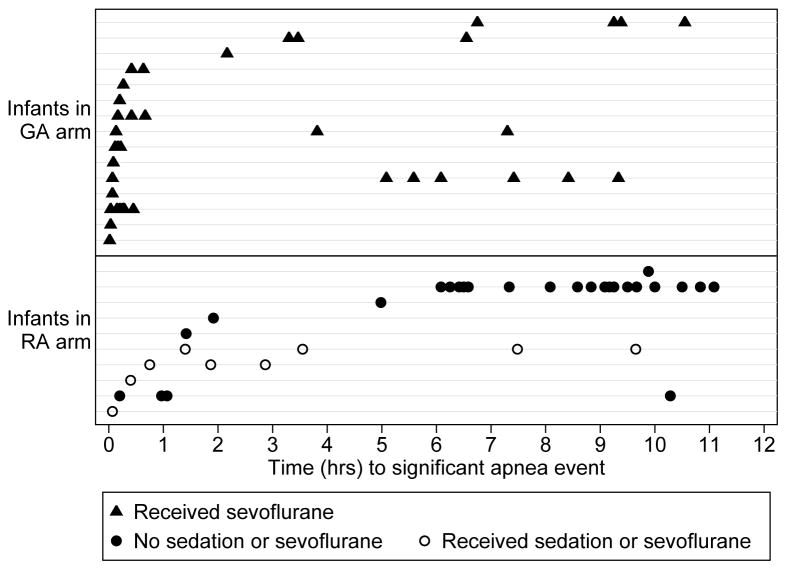

Twenty-five participants (3%) (10 in the RA and 15 in the GA arm) were recorded as having at least one apnea. Most apnea occurred in the early post-operative period (figure 2), especially in the GA group. Most infants with apnea had a single event; however one infant had 18 events. The proportions of infants with apnea-related outcomes in each group are presented in table 3 and the adjusted odds ratios for those outcomes in table 4. There was little evidence that allocation to RA or GA altered the odds of apnea in the overall period up to 12 hours after surgery (OR 0.63 with 95% CI 0.31 to 1.30, P=0.2133 by ITT). However for early apnea there was evidence that the odds of apnea were less in the RA arm (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.91, P =0.0367 by ITT). The odds for needing a significant intervention for early apnea were also less in the RA arm (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.64, P=0.0164). These effects were seen for both ITT and APP analyses; the effects being greater in the APP analysis. The level of intervention for apnea was also less in the RA arm (table 5). Of the infants with postoperative apnea, 86% in the GA arm and 50% in the RA arm received an intervention as tactile stimulation, supplemental oxygen, bag mask ventilation, or CPR to treat apnea. Details of the 9 (1.3%) children requiring the positive pressure ventilation or cardiopulmonary resuscitation within 5 days of surgery are shown in table 6. Of these 9 children, the 6 that had this event within 30 minutes of surgery were all these were in the GA arm (1.7% of the GA arm). However, 2 infants in the RA group did not have apnea in PACU yet experienced multiple apneic episodes starting 6–7 hours postoperatively on the inpatient ward which was treated with CPAP or bag and mask ventilation with transfer to intensive care.

Figure 2. Time to Apnoea Events in RA and GA.

Times of all apnoea events in all infants in RA and GA allocated groups with RA group further divided into those with no sedation or sevoflurane (closed circles), and those exposed to sevoflurane or sedation (closed squares). Each horizontal dashed line represents one infant. GA= General Anesthesia; RA = Regional Anesthesia.

Table 3.

Proportion of children with apnea related outcomes in each group.

| Outcome | Intention to treat - RA N=355 |

Intention to treat – GA N=356 |

As per protocol - RA N=286 |

RA to partial GA/sedation N=23 |

RA to full GA N=46 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any apnea (0–12hr) | 10 (3%) | 15 (4%) | 6 (2%) | 0 | 4 (9%) |

| Any early apnea (0–30min) | 3 (1%) | 12 (3%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Any late apnea (30min–12hr) | 8 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Any late apnea if discharged >=12hrs post-op | 8 (3%) | 6 (2%) | 6(3%) | 0 | 2 (5%) |

| Required significant intervention for apnea (0–5days)* | 7 (2%) | 18 (5%) | 4 (1%) | 0 | 3 (7%) |

| Required significant intervention for apnea (0–30min)* | 1 (<1%) | 12 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Required significant intervention for apnea (30min–12hr)* | 5 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Required significant intervention for late apnea if discharged >=12hrs post-op | 5 (2%) | 5 (2%) | 3(1%) | 0 | 2 (5%) |

| Required significant intervention for apnea after 12 hrs (12hr–5days)* | 2 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Any caffeine administered post-operatively (0–5days) | 2 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 |

GA= General Anesthesia; Hr = Hours; Min = Minutes; RA = Regional Anesthesia.

Data are presented as percentages of non-missing data. Partial GA/sedation is defined as receiving sevoflurane for only some of the surgery or receiving sedation. Full GA is defined as receiving sevoflurane from prior to knife to skin to the end of surgery.

Significant intervention for apnea is any intervention greater than simple tactile stimulation. GA as-per-protocol data are not presented as only 2 children in the GA arm had surgery cancelled so the data are very similar to the intention-to-treat data

Table 4.

Odds ratios for apnea related outcomes regional as compared with general anesthesia

| Outcome | Intention to treat | As per protocol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Any apnea (0–12hr) | 0.63 (0.31 to 1.30) | 0.2133 | 0.47 (0.17 to 1.32) | 0.1518 |

| Any early apnea (0–30min) | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.91) | 0.0367 | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.84) | 0.0359 |

| Any late apnea (30min–12hr) | 1.17 (0.41 to 3.33) | 0.7688 | 1.17 (0.44 to 3.14) | 0.7521 |

| Any apnea (30min–12hrs, if discharged ≥12hrs post-op ) | 1.42 (0.53 to 3.79) | 0.4857 | 1.46 (0.52 to 4.12) | 0.4713 |

| Any significant intervention for apnea (0–5day)* | 0.38 (0.21 to 0.69) | 0.0016 | 0.25 (0.11 to 0.57) | 0.0009 |

| Any significant intervention for early apnea (0–30min)* | 0.09 (0.01 to 0.64) | 0.0164 | n/a | |

| Any significant intervention for late apnea (30min–12hr)*# | 1.00 (0.26 to 3.84) | 0.9973 | 0.70 (0.18 to 2.67) | 0.5979 |

| Any significant intervention for apnea (30min–12hr, if discharged ≥12hrs post-operatively ) | 0.93 (0.23–3.73) | 0.9237 | 0.73 (0.19 to 2.77) | 0.6387 |

| Any significant intervention for apnea after 12hrs (12hr–5day) * | 0.51 (0.10 to 2.70) | 0.4292 | 0.62 (0.12 to 3.27) | 0.5741 |

| Any caffeine for apnea (0–5 day) | 0.45 (0.10 to 2.11) | 0.3098 | 0.50 (0.09 to 2.77) | 0.4255 |

Hr = Hours; Min = Minutes; RA = Regional Anesthesia

Significant intervention for apnea is any intervention greater than simple tactile stimulation

Note that any significant intervention for late apnea in the as per protocol analysis is modeled separately from early apnea because there were no events in the RA arm for early apnea.

Table 5.

Level of intervention

| Intervention | Intention to treat - RA | Intention to treat – GA | As per protocol - RA | RA to partial GA/sedation | RA to full GA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5days | N=18 | N=28 | N=11 | N=1 | N=6 | |

| Self limiting | 9 (50%) | 4 (14%) | 5 (45%) | 1 (100%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Tactile stimulation | 2 (11%) | 6 (21%) | 2 (18%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Oxygen with no PPV | 5 (28%) | 11 (39%) | 2 (18%) | 0 | 3 (50%) | |

| PPV, bag and mask or CPAP | 2 (11%) | 5 (18%) | 2 (18%) | 0 | 0 | |

| CPR | 0 | 2 (7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0–30min | N=7 | N=17 | N=2 | N=1 | N=4 | |

| Self limiting | 5 (71%) | 2 (12%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (100%) | 3 (75%) | |

| Tactile stimulation | 1 (14%) | 3 (18%) | 1 (50%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Oxygen with no PPV | 1 (14%) | 6 (35%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (25%) | |

| PPV, bag and mask or CPAP | 0 | 5 (29%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CPR | 0 | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 30min–12hr | N=15 | N=13 | N=11 | N=1 | N=3 | |

| Self limiting | 8 (53%) | 3 (23%) | 6 (55%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (33%) | |

| Tactile stimulation | 2 (13%) | 5 (38%) | 2 (18%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Oxygen with no PPV | 4 (27%) | 5 (38%) | 2 (18%) | 0 | 2 (67%) | |

| PPV, bag and mask or CPAP | 1 (7%) | 0 | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | |

| CPR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 30 min–12hr* | N=15 | N=12 | N=11 | N=1 | N=3 | |

| Self limiting | 8(53%) | 3 (25%) | 6 (55%) | 1 (100%) | 1 (33%) | |

| Tactile stimulation | 2(13%) | 4 (33%) | 2 (18%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Oxygen with no PPV | 4(27%) | 5(42%) | 2 (18%) | 0 | 2 (67%) | |

| PPV, bag and mask or CPAP | 1(7%) | 0 | 1 (9%) | 0 | 0 | |

| CPR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12hr–5days | N=4 | N=6 | N=4 | N=0 | N=0 | |

| Self limiting | 1 (25%) | 2 (33%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Tactile stimulation | 1 (25%) | 0 | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Oxygen with no PPV | 1 (25%) | 3 (50%) | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 | |

| PPV, bag and mask or CPAP | 1 (25%) | 0 | 1 (25%) | 0 | 0 | |

| CPR | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

CPAP= Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; CPR= Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; GA = General Anesthesia; PPV= Positive Pressure Ventilation; RA = Regional Anesthesia

These data include interventions for all events, including pauses in breathing that do not meet the criteria for apnea. Partial GA/sedation is defined as receiving sevoflurane for only some of the surgery or receiving sedation. Full GA is defined as receiving sevoflurane from prior to knife to skin to the end of surgery.

The denominator in this group is restricted to those who were discharged ≥12hrs.

Table 6.

Details of children that required positive pressure ventilation and/or CPR for post-operative apnea

| Child | Gestational age at birth (weeks) | Post menstrual age at surgery (weeks) | Group allocation | Relevant past history | Description of event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 29.1 | 40.4 | GA | Required two days CPAP after birth, uneventful anesthesia. | Brief apnea on arrival in PACU requiring stimulation, ten minutes oxygen saturation was 74% with heart rate 80, brief CPR and adrenaline given twice, tracheal tube inserted, rapid re-oxygenation and return of heart rate, tracheal tube removed 24 hours later, normal ECG and cardiac echo, Discharged home six days post surgery. |

| B | 33.1 | 49.0 | GA | Was having apnea pre-op, had four days with tracheal tube after birth and supplemental oxygen for nine days. Uncomplicated anesthesia. No apnea in PACU. Four apnea on ward between six and ten hours post surgery–requiring no intervention, discharged home next day with apnea monitor. | Day three after discharge had an apnea at home and an aunt performed brief CPR. Full and rapid recovery. Paramedics not called and child not readmitted to hospital. |

| C | 29.1 | 41.1 | RA | Child never discharged from hospital, required 62 days CPAP after birth, no respiratory support prior to surgery, uneventful surgery, discharged back to NICU post surgery. | 18 apneas, starting six hours post surgery, some with oxygen saturation <50% requiring bag and mask positive pressure ventilation, transferred to a neonatal unit at another hospital and nasal CPAP commenced, treated for suspected sepsis, given caffeine and discharged home seven days post surgery. |

| D | 29.0 | 39.6 | GA | Child never discharged from hospital, required eight days CPAP and 69 days supplemental oxygen after birth, no respiratory support prior to surgery, uneventful surgery. | Apnea shortly after arrival in PACU, treated with bag and mask positive pressure ventilation, transferred to PICU where had two further self limiting apnea, discharged home nine days post surgery. |

| E | 31.9 | 37.0 | GA | Unremarkable past history. No previous requirement for respiratory support. Uncomplicated anesthesia. | Oxygen saturation 59 on arrival to PACU – given bag and mask positive pressure ventilation. No further apnea or complications. |

| F | 30.0 | 39.7 | RA | Required 42 days of CPAP after birth, no respiratory support pre-operatively, uncomplicated spinal, several apneas intra-operatively, no apnea in recovery. Given tramadol prior to discharge from PACU | Five apneas starting on the ward seven hours post surgery, transferred to NICU, 12 hours post surgery further apnea and low oxygen saturation, given nasal CPAP and caffeine, discharged home two days post surgery, readmitted two weeks later with bronchiolitis. |

| G | 28.4 | 41.9 | GA | Two days CPAP after birth, uneventful anesthesia. | Apnea on arrival in PACU requiring bag and mask positive pressure ventilation, no further apnea, discharged home next day. |

| H | 34.9 | 53.4 | GA | Uneventful post natal period, uneventful anesthesia. | Apnea on arrival in PACU requiring bag and mask positive pressure ventilation, no further apnea, discharged home next day. |

| I | 26.6 | 37.6 | GA | Required 22 days CPA P after birth, uneventful anesthesia. | Six apneas in PACU requiring bag and mask positive pressure ventilation, given caffeine, discharged home two days after surgery. |

CPAP= Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; CPR= Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; ECG = Electrocardiogram; GA = General Anesthesia; NICU = Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; PACU = Post Anesthesia Care Unit; PICU = Pediatric Intensive Care Unit; PPV= Positive Pressure Ventilation; RA = Regional Anesthesia

Note for the entire study the mean gestational age at birth was 35.4 weeks and the mean post menstrual age at surgery was 45.6 weeks.

A brief exposure to anesthesia or sedation in the RA arm was not observed to increase apnea incidence, however if a full GA was administered the risk of apnea approached the risk associated with a planned GA (table 3).

The apnea rate was relatively low and this is reflected in a low absolute risk reduction (ARR). In all infants the ARR for early apnea with allocation to RA was 0.03 (95% CI 0.004 to 0.05). In preterm infants the ARR for early apnea with allocation to RA was 0.04 (95% CI 0.004 to 0.08) and in term infants the ARR for early apnea with allocation to RA was 0.006 (95% CI −0.006 to 0.02).

Characteristics of infants who had early and late apnea are listed in table 7 along with logistic regression models for determining factors associated with apnea table 8. Indeed all apnea occurred in ex-premature infants except one case. This one infant was born at 37 weeks and one day, had an unremarkable history, had a general anesthetic at approximately 44 weeks PMA and two apneas 20 minutes post-operatively that responded to gentle stimulation. Thus the incidence of apnea amongst preterm infants was 6.1% compared to 0.3% in term infants. After adjusting for group allocation there was evidence for an association between apnea and the following risk factors: prematurity, decreasing gestational age at birth, decreasing weight, decreasing PMA, a history of recent apnea, ever receiving methyl xanthine, ever receiving ventilation via a tracheal tube and ever needing oxygen support. Factors associated with late apnea were similar. Factors associated with early apnea were also similar, albeit with less evidence for an association with a history of recent apnea or ever requiring ventilation with a tracheal tube. The strongest risk factor for apnea was a history of prematurity (OR 21.87, 95%CI (4.38 to 109.24)). In appropriate sub-populations there was no evidence for an association between intra-operative use of tracheal tube or neuromuscular blocking agent and apnea (tables 9 & 10).

Table 7.

Summary data of children with and without apnea

| ITT | APP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Apnea (0–12hrs) | No Apnea | Early Apnea (0–30 min) | Late Apnea (30 min – 12 hrs) | Late Apnea (30 min – 12 hrs, if discharged ≥12hrs post-op) | Any Apnea (0–12hrs) | No Apnea | Early Apnea (0–30 min) | Late Apnea (30 min – 12 hrs) | Late Apnea (30 min – 12 hrs, if discharged ≥12hrs post-op) | |

| N=25 | N=686 | N=15 | N=15 | N=14 | N=21 | N=621 | N=13 | N=13 | N=12 | |

| Regional Anaesthesia | 10 (40%) | 345 (50%) | 3 (20%) | 8 (53%) | 8 (57%) | 6 (29%) | 280 (55%) | 1 (8%) | 6 (46%) | 6 (50%) |

| Age (PMA) at surgery (weeks) | 41.2 (3.9) | 45.7 (4.5) | 41.5 (4.3) | 40.6 (3.2) | 40.3 (3.1) | 41.1 (4.1) | 45.7 (4.5) | 41.4 (4.5) | 40.6 (3.4) | 40.3 (3.3) |

| Weight at surgery (kg) | 3.3 (1.2) | 4.3 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.7) | 3.4 (1.2) | 4.3 (1.1) | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.0 (0.8) |

| Haemoglobin level (g/100ml) | 9.8 (1.2) | 10.3 (2.0) | 10.1 (1.8) | 9.8 (2.0) | 9.7 (2.0) | 9.9 (1.8) | 10.3 (2.0) | 10.0 (1.8) | 10.0 (1.9) | 10.0 (2.0) |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 30.8 (2.8) | 35.7 (3.9) | 31.4 (3.3) | 31.0 (2.6) | 30.6 (2.1) | 31.1(2.9) | 35.6 (3.9) | 31.7 (3.3) | 31.3 (2.8) | 30.8 (2.3) |

| Less than 37 weeks gestational age | 24 (96 %) | 365 (53%) | 14 (93%) | 14 (93%) | 14 (100%) | 20 (95%) | 335 (54%) | 12 (92%) | 12 (92%) | 12 (100%) |

| Blood glucose (mmol/l) | 6 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.9) | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.8) | 6.1 (1.8) | 6.2 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.9) | 6.1 (1.1) | 6.2 (1.8) | 6.3 (1.8) |

| Apnea in previous 24 hours | 4 (16%) | 10 (1%) | 1 (7%) | 4 (27%) | 4 (29%) | 4 (19%) | 10 (2%) | 1 (8%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (33%) |

| Ever treated with a methyl xanthine | 14 (56%) | 98 (14%) | 7 (47%) | 10 (67%) | 10 (71%) | 12 (57%) | 91 (15%) | 6 (46%) | 9 (69%) | 9 (75%) |

| Ever ventilated with a tracheal tube pre-operatively | 8 (32%) | 83 (12%) | 3 (20%) | 6 (40%) | 6 (43%) | 6 (29%) | 76 (12%) | 3 (23%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (33%) |

| Ever needed oxygen therapy (apart from at birth) | 18 (72%) | 156 (23%) | 9 (60%) | 13 (87%) | 13 (93%) | 15 (71%) | 141 (23%) | 8 (62%) | 11 (85%) | 11 (92%) |

| Smoker in the household | 6 (24%) | 212 (31%) | 4 (27%) | 4 (27%) | 3 (21%) | 6 (29%) | 191 (31%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (31%) | 3 (25%) |

| Any opioids given prior to apnea* | 1 (4 %) | 14 (2%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 12 (2%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8%) | ||

| Minimum intra-operative temperature | 36.0 (0.8) | 36.0 (0.8) | 36.0 (0.6) | 36.0 (1.0) | 36.0 (1.0) | 36.0 (0.8) | 36.1 (0.8) | 36.0 (0.6) | 36.1 (0.9) | 36.2 (1.0) |

| Surgery duration (mins) | 30 (22 to 39) | 28 (20 to 39) | 29 (24 to 39) | 26 (20 to 41) | 28 (20 to 41) | 29 (22 to 32) | 27 (20 to 38) | 28 (24 to 32) | 26 (20 to 31) | 28 (20 to 36) |

APP = As Per Protocol; ITT = Intention to Treat; Mins = Minutes; PMA = Postmenstrual Age;

Data as frequency and percentage of non-missing data or mean and standard deviation.

Note that the data are incomplete with respect to opioid administration after 1 hour so only early apnea data are shown.

Table 8.

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with apnea by Intention-To-Treat and As-Per-Protocol

| Variable | Any apnea (0–12hrs) | Early apnea (0–30 min) | Late apnea (30 min – 12 hrs) | Late apnea (30 min – 12 hrs, if discharged ≥12hrs post-op) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Intention to Treat Analysis | ||||||||

| Age (PMA) at surgery (increase per week) | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.83) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.64 to 0.89) | 0.0008 | 0.69 (0.65 to 0.74) | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.83) | <0.0001 |

| Weight at surgery (increase per kg) | 0.33 (0.18 to 0.61) | 0.0003 | 0.48 (0.25 to 0.93) | 0.0294 | 0.26 (0.16 to 0.43) | <0.0001 | 0.24 (0.15 to 0.38) | <0.0001 |

| hemoglobin level (increase per unit) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.04) | 0.1618 | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.24) | 0.8517 | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.04) | 0.1381 | 0.89 (0.75 to 1.05) | 0.1589 |

| Gestational age (increase per week) | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.79) | <0.0001 | 0.76 (0.71 to 0.83) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.67 to 0.84) | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.83) | <0.0001 |

| Less than 37 weeks gestational age | 21.87 (4.38 to 109.24) | 0.0002 | 13.02 (2.22 to 76.45) | 0.0045 | 12.16 (3.14 to 47.08) | 0.0003 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | |

| Apnea in previous 24 hours | 12.60 (3.13 to 50.73) | 0.0004 | 3.46 (0.73 to 16.51) | 0.1189 | 26.72 (7.50 to 95.24) | <0.0001 | 24.94 (6.70 to 92.77) | <0.0001 |

| Ever treated with a methyl xanthine | 8.74 (5.05 to 15.12) | <0.0001 | 6.16 (2.86 to 13.29) | <0.0001 | 14.44 (6.56 to 31.77) | <0.0001 | 13.28 (4.83 to 36.52) | <0.0001 |

| Ever ventilated with a tracheal tube | 3.55 (1.77 to 7.11) | 0.0004 | 1.83 (0.54 to 6.21) | 0.3339 | 5.39 (1.95 to 14.89) | 0.0012 | 4.51 (1.72 to 11.78) | 0.0021 |

| Ever needed oxygen therapy (apart from at birth) | 9.10 (4.84 to 17.14) | <0.0001 | 5.23 (1.84 to 14.87) | 0.0019 | 23.02 (7.44 to 71.17) | <0.0001 | 33.47 (4.76 to 235.39) | 0.0004 |

| Smoker in the household | 0.66 (0.32 to 1.35) | 0.2519 | 0.71 (0.25 to 2.01) | 0.5238 | 0.74 (0.20 to 2.73) | 0.6571 | 0.58 (0.17 to 1.92) | 0.3726 |

| Blood glucose level (increase per unit) | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.15) | 0.6298 | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.18) | 0.8477 | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.20) | 0.7958 | 1.03 (0.90 to 1.19) | 0.6551 |

| Minimum intra-operative temperature (increase per degree) | 0.93 (0.46 to 1.88) | 0.8321 | 1.01 (0.54 to 1.90) | 0.9675 | 0.93 (0.20 to 4.44) | 0.9308 | 1.03 (0.17 to 6.09) | 0.9755 |

| Surgery duration (increase per min) | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0.3827 | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.3995 | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.2388 | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.1793 |

| As- Per-Protocol Analysis | ||||||||

| Age (PMA) at surgery (increase per week) | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.84) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.63 to 0.88) | 0.0005 | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.76) | <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.63 to 0.76) | <0.0001 |

| Weight at surgery (increase per kg) | 0.38 (0.22 to 0.66) | 0.0006 | 0.52 (0.29 to 0.94) | 0.0295 | 0.27 (0.14 to 0.53) | 0.0001 | 0.24 (0.13 to 0.45) | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin level (increase per unit) | 0.93 (0.78 to 1.12) | 0.4632 | 0.97 (0.75 to 1.27) | 0.8433 | 0.96 (0.79 to 1.17) | 0.6973 | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.19) | 0.8062 |

| Gestational age (increase per week) | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.81) | <0.0001 | 0.77 (0.69 to 0.87) | <0.0001 | 0.76 (0.68 to 0.86) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.65 to 0.86) | <0.0001 |

| Less than 37 weeks gestational age | 17.26 (3.54 to 84.05) | 0.0004 | 10.85 (1.75 to 67.32) | 0.0105 | 9.76 (3.02 to 31.53) | 0.0001 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | |

| Apnea in previous 24 hours | 14.65 (3.62 to 59.22) | 0.0002 | 3.79 (0.71 to 20.32) | 0.1204 | 27.86 (9.19 to 84.47) | <0.0001 | 26.33 (8.36 to 82.96) | <0.0001 |

| Ever treated with a methyl xanthine | 8.81 (4.86 to 15.98) | <0.0001 | 5.91 (2.16 to 16.19) | 0.0005 | 15.05 (7.64 to 29.68) | <0.0001 | 14.97 (6.07 to 36.62) | <0.0001 |

| Ever ventilated with a tracheal tube | 2.98 (1.28 to 6.92) | 0.0112 | 2.24 (0.60 to 8.30) | 0.2286 | 3.36 (1.22 to 9.25) | 0.0192 | 2.80 (1.03 to 7.60) | 0.0429 |

| Ever needed oxygen therapy (apart from at birth) | 8.98 (4.02 to 20.06) | <0.0001 | 5.69 (1.65 to 19.63) | 0.0060 | 19.39 (6.52 to 57.65) | <0.0001 | 30.25 (3.63 to 252.18) | 0.0016 |

| Smoker in the household | 0.83 (0.37 to 1.89) | 0.664 | 0.88 (0.27 to 2.90) | 0.8337 | 0.94 (0.27 to 3.28) | 0.9168 | 0.70 (0.23 to 2.12) | 0.5187 |

| Blood glucose level (increase per unit) | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.17) | 0.23 | 1.02 (0.87 to 1.21) | 0.7781 | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.19) | 0.1348 | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 0.0712 |

| Minimum intra-operative temperature (increase per degree) | 1.14 (0.37 to 3.52) | 0.8216 | 1.12 (0.38 to 3.29) | 0.8423 | 1.38 (0.23 to 8.31) | 0.7240 | 1.68 (0.19 to 14.67) | 0.6386 |

| Surgery duration (increase per min) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.3497 | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | 0.2513 | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.2704 | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.2673 |

Hrs = Hours; Min = Minutes; PMA = Postmenstrual Age

The bivariable regression analyses were adjusted for treatment allocation in addition to each factor listed in the Table. We planned to include the use of opioid administration prior to apnea as a predictor of apnea, but the number of apnea events was too low.

Table 9.

Association between the use of a tracheal tube and apnea

| Outcome | Tracheal tube N=281 |

No tracheal tube N=73 |

OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any apnea (0–12hr) | 11 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 0.72 (0.18 to 2.85) | 0.6406 |

| Any early apnea (0–30min) | 8 (3%) | 4 (5%) | 0.44 (0.09 to 2.08) | 0.2981 |

| Any late apnea (30min–12hr) | 6 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1.37 (0.06 to 30.22) | 0.8413 |

| Any Apnea (30 min–12hr, if discharged ≥12hrs post-op) | 5 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1.39 (0.71 to 14.63) | 0.9873 |

GA = General Anesthesia; Hr = Hours; Min = Minutes

In the GA arm 281 (79%) of infants had a tracheal tube. There were four cases where use of a tracheal tube was not recorded. There was no evidence for an association between tracheal tube and apnea in the 354 infants in the GA arm without protocol violation.

Table 10.

Association between the use of neuromuscular blocking agents and apnea

| Outcome | Neuromuscular blocking agent used N= 122 |

No Neuromuscular blocking agent used N= 159 |

OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any apnea (0–12hr) | 5 (4%) | 6 (4%) | 0.96 (0.29 to 3.13) | 0.9473 |

| Any early apnea (0–30min) | 3 (2%) | 5 (3%) | 0.75 (0.21 to 2.67) | 0.6579 |

| Any late apnea (30min–12hr) | 4 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 2.87 (0.88 to 9.36) | 0.0798 |

| Any Apnea (30 min–12hr, if discharged ≥12hrs post-op) | 4 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 6.73 (0.62 to 55.60) | 0.1235 |

GA = General Anesthesia; Hr = Hours; Min = Minutes

In the GA arm that had a tracheal tube 122(43.6%) of infants had a neuromuscular blocking agent administered. There was one case where a tracheal tube was used but it was not recorded if a neuromuscular blocking agent was used. There was no evidence for an association between tracheal tube and apnea in the 280 infants that had a tracheal tube in the GA arm without protocol violation.

Early apnea was also a strong predictor of late apnea. In a model with late apnea as the outcome and including gestational age and type of anesthetic, the odds ratios for early apnea were 24.21(95%CI: 5.88 to 99.66, P<0.0001) for the ITT analysis and 46.52 (95%CI: 7.71 to 280.59, P<0.0001) for APP analysis. For the APP analysis, of the 13 children that had late apnea only five had an early apnea, giving a low sensitivity of 0.38. While early apnea is a strong predictor of late apnea it is not a sensitive measure for late apnea.

Other outcome data are shown in table 11. Anesthesia time was shorter in the RA arm (51 versus 66 minutes) with little evidence for any difference in surgical times (28 minutes each). Infants randomized to RA had a substantially greater mean minimum systolic blood pressure (70.7 mmHg versus 54.8 mmHg) and were less likely to need an intervention for hypotension during anesthesia (7% versus 19%). Infants randomized to RA had a slightly higher minimum intra-operative heart rate (133.9 versus 127.6 beats per minute) and were slightly warmer (36.1 versus 36.0 degrees Celsius). Infants randomized to RA were less likely to have a significant oxygen desaturation post-operatively (1% versus 4%), and slightly shorter times to first feed (31 versus 36 minutes). Approximately 20% of children were discharged prior to 12 hours; discharge times were similar in each arm (table 12).

Table 11.

Non-apnea related outcomes in each group.

| Outcome | Intention to treat - RA N=355 |

Intention to treat – GA N=356 |

As per protocol RA N=286 |

Intention-to-treat | As-per-protocol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-operative data (events in operating theatre) | |||||||

| (Median (IQR))Minimum oxygen saturation ** | 97 (95 to 98) | 97 (95 to 99) | 97 (95 to 98) | ||||

| Oxygen saturation below 95% # | 77 (22%) | 75 (21%) | 63 (22%) | 1.05 (0.66 to 1.67) | 0.8290 | 1.04 (0.62 to 1.75) | 0.8744 |

| Minimum systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 70.7 (15.3) | 54.8 (11.7) | 73.2 (14.3) | 15.90 (13.21 to 18.58) | <0.0001 | 18.33 (15.29 to 21.37) | <0.0001 |

| Intervention for hypotension | 26 (7%) | 69 (19%) | 19 (7%) | 0.34 (0.21 to 0.53) | <0.0001 | 0.29 (0.17 to 0.50) | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) Minimum heart rate (beats/minute) | 133.9 (16.4) | 127.6 (15.2) | 134.3 (16.8) | 6.29 (2.26 to 10.32) | 0.0022 | 6.67 (2.64 to 10.71) | 0.0012 |

| Mean (SD) Minimum temperature (degrees Celsius) | 36.1 (0.9) | 36.0 (0.6) | 36.2 (0.9) | 0.16 (0.04 to 0.28) | 0.0109 | 0.19 (0.07 to 0.32) | 0.0024 |

| (Median (IQR))Anesthesia time: from start skin prep for regional or induction of GA, to out of operating theatre (mins) * | 51 (40 to 69) | 66 (52 to 85) | 47(39 to 61) | 0.81 (0.75 to 0.87) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.81) | <0.0001 |

| (Median (IQR)) Surgery time: from knife to skin to last stitch (mins)* | 28 (20 to 38) | 28 (20 to 40) | 26 (19 to 35) | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.03) | 0.3863 | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.01) | 0.0840 |

| Post anesthesia care data | |||||||

| (Median (IQR)) Time to first feed (mins)* | 31 (16 to 66) | 36 (19 to 95) | 29 (15 to 60) | 0.77 (0.59 to 1.00) | 0.0507 | 0.69 (0.51 to 0.92) | 0.0132 |

| Received opioid analgesia within 1hr of surgery | 3 (1%) | 9 (3%) | 1 (<1%) | 0.32 (0.09 to 1.18) | 0.0866 | 0.15 (0.02 to 0.96) | 0.0452 |

| Oxygen saturation <80% in first hour after surgery | 4 (1%) | 13 (4%) | 1 (<1%) | 0.31 (0.10 to 0.95) | 0.0402 | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.49) | 0.0046 |

| Oxygen saturation <95% in first hour after surgery# | 70 (20%) | 98 (28%) | 50 (17%) | 0.64 (0.50 to 0.82) | 0.0004 | 0.55 (0.42 to 0.71) | <0.0001 |

| Minimum oxygen saturation within 1hr of surgery ** | 96 (95 to 98) | 96 (94 to 98) | 97 (95 to 98) | ||||

| Requiring any respiratory support at 1hr post surgery | 15 (4%) | 15 (4%) | 8 (3%) | 0.99 (0.49 to 2.00) | 0.9808 | 0.63 (0.31 to 1.29) | 0.2092 |

| Requiring nasal CPAP within 12 hrs of surgery | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 1.01 (0.18 to 5.60) | 0.9884 | N/A | |

| Requiring any positive pressure mask ventilation within 12 hrs of surgery | 5 (1%) | 20 (6%) | 2 (1%) | 0.21 (0.09 to 0.51) | 0.0006 | 0.11 (0.01 to 0.84) | 0.0333 |

| Tracheal intubation within 12 hrs of surgery | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Any stridor within 5 days of surgery | 1 (<1%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0.27 (0.03 to 2.11) | 0.2119 | 0.32 (0.04 to 2.74) | 0.2982 |

CPAP= Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; GA= General Anesthesia; IQR = Interquartile Range; Mins = Minutes; RA = Regional Anesthesia; SD = Standard Deviation.

GA as-per-protocol summary data are not presented as only 2 children in the GA arm had surgery cancelled so in most instances the data are very similar to the intention-to-treat data. Percentages given as percentages of non-missing data. N/A: insufficient number of events to estimate treatment effect with logistic regression model.

Median and IQR are presented, treatment effect is estimated for the log-transformed variable and thus gives the multiplicative increase in outcome in the GA arm.

Data strongly skewed so no comparative statistics performed.

Odds ratio for child ever having at least one measurement <95% oxygen saturation during surgery. This measure was defined post-hoc since the distribution of the minimum oxygen saturation was strongly skewed. The investigators who defined the 95% cut off were blind to the oxygen saturation data.

Table 12.

Post anesthesia care location and discharge times in each group.

| Intention to treat - RA N=355 |

Intention to treat – GA N=356 |

As per protocol RA N=286 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-operative recovery location | |||

| Post anesthesia care unit | 304 (88%) | 301 (88%) | 247 (87%) |

| Step down facility | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) |

| Neonatal ward | 1 (<1%) | 3 (1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| General ward | 14 (4%) | 20 (6%) | 13 (5%) |

| Neonatal intensive care | 11 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 9 (3%) |

| General paediatric intensive care | 15 (4%) | 13 (4%) | 12 (4%) |

| Discharge from hospital times | |||

| 30minutes – 2 hrs | 20 (6%) | 17 (5%) | 15 (5%) |

| >2–6 hrs | 37 (10%) | 41 (12%) | 32 (11%) |

| >6–<12 hrs | 14 (4%) | 10 (3%) | 12 (4%) |

| 12hrs–5days | 275 (78%) | 279 (79%) | 217 (77%) |

| >5days | 7 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 7 (2%) |

GA = General Anesthesia; RA = Regional Anesthesia

Discussion

In this trial there was no evidence that RA reduced the overall risk of observed apnea. In subgroup analyses RA did reduce the risk of early post-operative apnea; however there was no evidence that RA reduced the risk of late apnea. RA also reduced the degree of post-operative oxygen desaturation and the level of intervention for apnea, implying that apnea after RA was not only less frequent but of lesser clinical importance. However, overall the incidence of bedside intervention for postoperative apnea was appreciable by current standards of patient safety in pediatric anesthesia.11–13 Infants in the GA arm also had lower minimum blood pressures intra-operatively. The strongest risk factor for apnea was prematurity.

Strengths of this trial include the size of the study, being multinational and hence increasing external validity and the use of modern anesthetic agents. The trial does have a number of limitations. Firstly, the GAS study was primarily designed to address the issue of potential neurotoxicity of GA. Exclusion criteria reflect this aim. The trial excluded infants born extremely premature and some infants with significant co-morbidity. It is possible that benefits of RA and risk factors for apnea are different in these populations. Secondly, in this trial we relied on staff and researchers to identify apnea. Apnea incidence depends on the type of monitoring used.3 In our trial, few sites used impedance pneumography and none used more sensitive techniques such as thermistry or capnography. It would not have been feasible to obtain and standardize this monitoring across all sites. Similarly the infants were only constantly monitored for the first hour. After that, monitoring was as per routine or clinical judgment. Our results therefore likely underestimate the true rate of apnea, especially late apnea. We are also unable to comment on apnea that occurred after discharge from hospital – thus we performed a post hoc analysis for late apnea where we only included children that were not discharged prior to 12 hours. Given the uncertainty surrounding the significance of brief apnea, and the likelihood that our trial may have missed brief apnea, it is important to consider not only the recorded apnea but also the incidence of the significant clinical interventions. Our trial was large enough to give some indication of relative frequency of these events; RA reducing the odds for such events. Recording and comparing these events may be more clinically relevant than capturing all brief self-resolving apnea events. The incidence of positive pressure ventilation or CPR occurred in 9 infants overall (1.3%) and in 6 infants (0.8%) in PACU. The events occurred in these six children within 30 minutes of the end of surgery and all these were in the GA arm, and all were ex-premature infants. This non-trivial event rate underscores the need for close monitoring in this population. 11–13 Another limitation to the trial was lack of blinding. It was impossible to blind nursing staff because an infant recovering from spinal would often have no lower limb motor function, in the GA arm the airway is often secured by tape that leaves a distinctive mark on the infant’s sensitive skin and in the RA arm a puncture site would be visible in the infant’s back. Failure of the RA technique may also confound some of the outcome measures and thus it is important that both ITT and APP data and analyses are considered. Importantly some advantage was still seen with the ITT analysis implying the failure rate does not substantially diminish the advantage of planning to perform an awake regional technique. The factors associated with failure are complex and are described in another publication in Anesthesiology. Finally, the frequency of apnea was low. Although there were enough events to draw some conclusions, the low event rate precluded identifying independent risk factors in multivariable models. The overall rate of apnea in our trial was 3%. Cote et al performed a combined analysis of apnea in ex-premature infants from five previous studies. He reported a combined apnea rate of 25%; however the rate in the contributing studies varied from 5% to 49%.3 Reported rates of apnea vary depending on its definition, the detection method used and the population studied. Although the definition used by the National Institute of Health, United States for serious apnea is 20 seconds duration for apnea of prematurity, most (but not all) studies examining post-operative apnea have used a duration of >15 seconds or >10 seconds if accompanied by either hypoxia or bradycardia.14 For consistency we chose the definition used most widely for post-operative apnea. The relatively low rate of apnea in our study may be due to method used to detect apnea. Those who defined apnea using continuous recording devices (impedance pneumography with or without nasal thermistry) found rates of 31% to 49%.5,15–19 Those studies that relied on nursing observation and/or responding to alarming from impedance pneumography found rates of 5% to 10%.2,20 Also in our study only half the infants in our trial were ex-premature. All bar one infant with apnea was premature, giving a rate of apnea in ex-premature infants as 6%. This is consistent with previous studies that have failed to identify apnea in term infants.21,22 Cote et al found that anemia was a strong predictor of apnea. In contrast we found no evidence for an association between anemia and apnea.

Differentiating early and late apnea is important as the etiology and management may differ. Determining which infants are at risk of late apnea may help identify those that require extended observation. When considering late apnea we found a similar and low rate in both groups. It is not possible from our results to determine how much this apnea rate is related to the surgery and how much they reflect the “back ground” rate of apnea in these children.

In our trial we found that early apnea is a strong predictor of late apnea. However, early apnea is an insensitive measure. Thus while any infant with early apnea is at increased risk of subsequent apnea, absence of early apnea is not a guarantee that the infant will not have a late apnea – more than half of the infants with late apnea had no early apnea, confirming previous study results18.

In this trial the GA arm had a substantially lower average minimum systolic blood pressure. The ideal blood pressure for infants undergoing surgery is unknown. These data will be further described in a subsequent publication.

The first implication of our trial is that aiming to perform an awake-regional anesthetic has distinct benefits in reducing the odds for apnea that required significant intervention in the post anesthesia care unit. If the surgeon and family agree, if there are no contra-indications, and if the anaesthetist is familiar with the technique, then awake-regional anesthesia is potentially the preferred technique in this population. However, our study highlights the importance of a back-up plan for GA since the incidence of failure of RA is appreciable (20%). The second implication of our trial relates to which children should be monitored for an extended period postoperatively. To reduce the risk of late apnea surgery should be delayed as long as safe and feasible, and extended monitoring should be considered for at least those children who are premature, and those who have early post-operative apnea. The monitoring should occur in a location where healthcare providers are trained in neonatal apnea intervention and will be able to respond quickly to an alarm. However, while awake-regional anesthesia may still be preferable for reasons mentioned above (Page 26, Paragraph 4), we found no evidence that it reduces the risk of late apnea in this population.

Our study excluded many infants that were extremely premature or had significant co-morbidity. Further studies are required to quantify the benefits of awake-regional anesthesia in these high risk groups. While our study recruited more participants than all previous similar studies combined, it may still be too few to identify rare and serious complications such as death from apnea after discharge, or sub-dural hematoma or central nervous system infection from awake-regional anesthesia. Larger ongoing surveillance studies are needed to quantify these risks.

Final Box Summary Statement.

What we already know about this topic

Whether awake regional anesthesia reduces the risk of apnea compared to general anesthesia in infants is unclear

What this article tells us that is new

In a secondary analysis of over 700 infants < 60 weeks postmenstrual age randomized to regional or general anesthesia for inguinal herniorraphy, there was no difference in the incidence apnea in the first 12 postoperative hours (primary outcome measure), although early apnea in the first 30 min was less with regional

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all of these collaborators for their assistance and advice with the GAS study: Mark Fajgman MBBS, FANZCA Department of Anaesthesia, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Australia; Daniela Tronconi RN Department of Anesthesia, Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy; David C van der Zee MD, PhD Department of Pediatric Surgery, Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Centre Utrecht, The Netherlands; Jan BF Hulscher MD, PhD Department of Surgery, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen University, Groningen, The Netherlands; Rob Spanjersberg RN Department of Anesthesiology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen University, Groningen, The Netherlands; Michael J Rivkin MD Department of Neurology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, Massachusetts; Michelle Sadler-Greever RN Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington and Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, , Seattle, Washington; Debra Faulk MD Department of Anesthesiology, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver, Colorado and Department of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, Colorado; Danai Udomtecha MD, Sarah Titler MD, Susan Stringham RN, Pamela Jacobs RN and Alicia Manning ADN Department of Anesthesia, The University of Iowa Hospital and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa,; Roxana Ploski BS and Alan Farrow-Gillespie MD Department of Anesthesiology, Children’s Medical Center Dallas, Dallas, Texas and Department of Anesthesiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas and Dallas and Children’s Medical Center at Dallas and Outcome Research Consortium, Dallas, Texas; Timothy Cooper MA, PsyD Division of Developmental Medicine & the Center for Child Development, Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tennessee,; Elizabeth Card MSN, APRN, RN, FNP-BC, CPAN, CCRP Perioperative Clinical Research Institute, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; Wendy A Boardman BA Department of Anesthesiology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, , New Hampshire; Theodora K Goebel RN, BSN, CCRC Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Appendix 1. GAS study Consortium

Australia

Andrew J Davidson MD and Geoff Frawley MBBS (Anaesthesia and Pain Management Research Group, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia and Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia and Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia); Pollyanna Hardy MSc (National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Clinical Trials Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom); Sarah J Arnup MBiostat and Katherine Lee PhD (Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics Unit, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia); Rodney W Hunt PhD (Department of Neonatal Medicine, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia and Neonatal Research Group, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia and Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia); Robyn Stargatt PhD (School of Psychological Science, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia and Child Neuropsychology Research Group, Murdoch Childrens Research Institut e, Melbourne, Australia); Suzette Sheppard BSc, Gillian Ormond MSc, and Penelope Hartmann B Psych (Hons) (Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia); Philip Ragg MBBS (Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia); Marie Backstrom RN Cert (Department of Anaesthesia, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Australia); David Costi BMBS (Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia, Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, Australia); Britta S von Ungern-Sternberg MD PhD (Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management, Princess Margaret Hospital for Children, Perth, Australia and Pharmacology, Pharmacy and Anaesthesiology Unit, School of Medicine and Pharmacology, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia)

New Zealand

Niall Wilton MRCP and Graham Knottenbelt MBBCH (Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia and Operating Rooms, Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand)

Italy

Nicola Disma MD, Giovanni Montobbio MD, Leila Mameli MD, Pietro Tuo MD, and Gaia Giribaldi MD (Department of Anesthesia, Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy); Alessio Pini Prato MD (Department of Pediatric Surgery, Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy); Girolamo Mattioli MD (DINOGMI Department, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy); Andrea Wolfler MD, Francesca Izzo MD, and Ida Salvo MD (Department of Anesthesiology & Paediatric Intensive Care, Ospedale Pediatrico ‘Vittore Buzzi’, Milan, Italy); Valter Sonzogni MD, Bruno Guido Locatelli MD, and Magda Khotcholava MD (Department of Anaesthesia, Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy)

The Netherlands

Jurgen C de Graaff MD PhD, Jose TDG van Gool RN, Sandra C Numan MSc, and Cor J Kalkman MD PhD (Department of Anesthesiology, Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Centre Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands); JHM Hagenaars BSc, Anthony R Absalom MBChB FRCA MD, Frouckje M Hoekstra MD, and Martin J Volkers MD (Department of Anesthesiology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen University, Groningen, The Netherlands)

Canada

Davinia E Withington BM (Department of Anesthesia, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, Canada and McGill University, Montreal, Canada); Koto Furue MD (Département d’Anesthésie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montreal, Canada); Josee Gaudreault MScA (Department of Anesthesia, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, Canada)

USA

Mary Ellen McCann MD, Charles Berde MD, Sulpicio Soriano MD, Vanessa Young RN, BA, Navil Sethna MD, Pete Kovatsis MD, and Joseph P Cravero MD (Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, Massachusetts); David Bellinger PhD and Jacki Marmor M.Ed (Department of Neurology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, Massachusetts); Anne Lynn MD, Iskra Ivanova MD, Agnes Hunyady MD, and Shilpa Verma MD (Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington and Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, , Seattle, Washington); David Polaner MD, FAAP (Department of Anesthesiology, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver, Colorado and Department of Anesthesiology, University of Colorado, Denver, Colorado); Joss Thomas MD, Martin Meuller MD, and Denisa Haret MD (Department of Anesthesia, The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, , Iowa City, Iowa); Peter Szmuk MD, Jeffery Steiner DO, and Brian Kravitz MD (Department of Anesthesiology, Children’s Medical Center Dallas, Texas and Department of Anesthesiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas and Children’s Medical Center at Dallas and Outcome Research Consortium, Dallas, Texas); Santhanam Suresh MD (Department of Pediatric Anesthesiology, Ann & Robert H Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois); Stephen R Hays MD (Department of Pediatric Anesthesia, Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tennessee); Andreas H Taenzer MD MS (Department of Anesthesiology ,Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, , New Hampshire); Lynne G Maxwell MD (Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Robert K Williams MD (Department of Anesthesia and Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Vermont Children’s Hospital, Burlington, Vermont)

UK

Neil S Morton MD FRCA (Academic Unit of Anaesthesia, Pain and Critical Care, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK and Department of Anaesthesia, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, UK); Graham T Bell MBChB (Department of Anaesthesia, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, UK); Liam Dorris DClinPsy and Claire Adey MA(Hons) (Fraser of Allander Unit, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, UK); Oliver Bagshaw MB ChB, FRCA, FFICM (Department of Anaesthesia, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, UK); Anthony Chisakuta BSc (HB), MB ChB, MSc, MMEDSc, FFARCSI (Department of Anaesthetics, Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, Belfast, UK); Ayman Eissa MD (Anaesthetic Department, Sheffield Children’s Hospital, Sheffield, UK); Peter Stoddart MB BS, BSc, MRCP (UK), FRCA (Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia, Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol, UK); Annette Davis MB ChB, FRCA (Department of Anaesthesia, Pain Relief and Sedation, Alder Hey Childrens’ NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK)

Trial Steering Committee

Prof Paul Myles (chair); Members – AJD, MEMcC, NSM, ND, DW, JCdeG, GF, RWH, Dr David Bellinger, Dr Charles Berde, Prof Andy Wolf, Prof Neil McIntosh, Prof John Carlin, Prof Kate Leslie, Attendees-GO, PH, SA, RS, Ms Suzette Sheppard, Dr Katherine Lee.

Data Monitoring Committee

Dr Jonathan de Lima (chair), Prof Greg Hammer, Prof David Field, Prof Val Gebski, Prof Dick Tibboel

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding Institutions:

All hospitals and centers were generously supported by anesthesiology departmental funding. In addition to this funding, specific grants received for this study are as follows: Australia and New Zealand: The Australian National Health & Medical Research Council, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia; Australian and New Zealand College of Anesthetists, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. This study was supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Anaesthesia, Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Anaesthesia and Pain Management, Princess Margaret Hospital for Children, Perth, Western Australia, Australia; Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia, Women’s Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia and Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia and Operating Rooms, Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand. United States: National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, Maryland; Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts: Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, Washington; Department of Anesthesiology, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver, Colorado; Department of Anesthesia, University of Iowa Hospital, Iowa City, Iowa; Department of Anesthesiology, Children’s Medical Center Dallas, Dallas, Texas; Department of Pediatric Anesthesiology, Anne and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois; Department of Anesthesiology, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire; Department of Pediatric Anesthesia, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Department of Anesthesia and Pediatrics, The University of Vermont/Fletcher Allen Health Care, Burlington, Vermont. Italy: Italian Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy; Department of Anesthesia, Istituto Giannina Gaslini, Genoa, Italy; Department of Anesthesiology & Paediatric Intensive Care, Ospedale Vittore Buzzi, Milan, Italy and Department of Anaesthesia, Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy. Netherlands: Fonds NutsOhra, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Department of Anesthesiology, Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands and Department of Anesthesiology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands Canada: Canadian Institute of Health Research, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Pfizer Canada Inc., Kirkland, Quebec, Canada; Department of Anesthesia, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada and Département d’Anesthésie, CHU Sainte-Justine, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. United Kingdom: Health Technologies Assessment-National Institute for Health Research United Kingdom, Southampton, United Kingdom. Anesthesiology Departmental Funding: Department of Anaesthesia, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, United Kingdom; Department of Anaesthesia, Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom; Anaesthetic Department, Sheffield Children’s Hospital, Sheffield, United Kingdom; Department of Paediatric Anaesthesia, Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol, United Kingdom; Department of Anaesthetics, Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, Belfast, United Kingdom and Department of Anaesthesia, Pain Relief and Sedation, Alder Hey Childrens’ NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Krane EJ, Haberkern CM, Jacobson LE. Postoperative apnea, bradycardia, and oxygen desaturation in formerly premature infants: Prospective comparison of spinal and general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:7–13. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malviya S, Swartx J, Lerman J. Are All Preterm Infants Younger than 60 Weeks Postconceptual Age at Risk for Postanesthetic Apnea? Anesthesiology. 1993;78:1076–81. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199306000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cote CJ, Zaslavsky A, Downes JJ, Kurth CD, Welborn LG, Warner LO, Malviya SV. Postoperative Apnea in Former Preterm Infants after Inguinal Herniorrhaphy: A Combined Analysis. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:809–22. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somri M, Gaitini L, Vaida S, Collins G, Sabo E, Mogilner G. Postoperative outcome in high-risk infants undergoing herniorrhaphy: Comparison between spinal and general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:762–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welborn LG, Rice LJ, Hannallah RS, Broadman LM, Ruttimann UE, Fink R. Postoperative Apnea in Former Preterm Infants: Prospective Comparison of Spinal and General Anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:838–42. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199005000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher DM. When Is the Ex-Premature Infant No Longer at Risk for Apnea? Anesthesiology. 1995;82:807–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199504000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craven PD, Badawi N, Henderson-Smart DJ, O’Brien M. Regional (spinal, epidural, caudal) versus general anaesthesia in preterm infants undergoing inguinal herniorrhaphy in early infancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD003669. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [Last Accessed: January 27th 2015]; http://www.thelancet.com/protocol-reviews/09PRT-9078.

- 9.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, Volume 1: Statistics; Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press; 1967. pp. 221–33. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.bsmsp/1200512988. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurth CD, Tyler D, Heitmiller E, Tosone SR, Martin L, Deshpande JK. National pediatric anesthesia safety quality improvement program in the United States. Anesth Analg. 2014;119:112–21. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murat I, Constant I, Maud’huy H. Perioperative anaesthetic morbidity in children: A database of 24,165 anaesthetics over a 30-month period. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:158–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiret L, Nivoche Y, Hatton F, Desmonts JM, Vourc’h G. Complications related to anaesthesia in infants and children. A prospective survey of 40240 anaesthetics. Br J Anaesth. 1988;61:263–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/61.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pediatrics; National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on Infantile Apnea and Home Monitoring; Sept 29 to Oct 1, 1986; 1987. pp. 292–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welborn LG, de Soto H, Hannallah RS, Fink R, Ruttimann UE, Boeckx R. The Use of Caffeine in the Control of Post-anesthetic Apnea in Former Premature Infants. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:796–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198805000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]