Abstract

Objective

Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), especially those targeting beta-2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), are well known to activate endothelial cells, monocytes, and platelets, with prothrombotic implications. In contrast, the interaction of aPL with neutrophils has not been extensively studied. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) have recently been recognized as an important activator of the coagulation cascade, as well as an integral component of arterial and venous thrombi. Here, we hypothesized that aPL might activate neutrophils to release NETs, thereby predisposing to the arterial and venous thrombosis inherent to the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

Methods

Neutrophils, sera, and plasma were prepared and characterized from patients with primary APS (n=52), or from healthy volunteers. No patient carried a concomitant diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Results

Sera and plasma from patients with primary APS have elevated levels of both cell-free DNA and NETs, as compared to healthy volunteers. Freshly-isolated APS neutrophils are predisposed to high levels of spontaneous NET release. Further, APS-patient sera, as well as IgG purified from APS patients, stimulate NET release from control neutrophils. Human aPL monoclonals, especially those targeting β2GPI, also enhance NET release. The induction of APS NETs can be abrogated with inhibitors of reactive oxygen species formation and toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Highlighting the potential clinical relevance of these findings, APS NETs promote thrombin generation.

Conclusion

Neutrophil NET release warrants further investigation as a novel therapeutic target in APS.

INTRODUCTION

The antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease of unknown cause associated with elevated titers of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL). aPL predispose to arterial and venous thrombosis, as well as fetal loss (1). While first described in association with SLE (2), APS is now well recognized to also exist as a primary autoimmune syndrome, with thrombosis and pregnancy loss as its cardinal manifestations, and with other associated features including thrombocytopenia, livedo reticularis, cognitive dysfunction, seizure disorder, and renal vasculopathy (1). Importantly, APS is relatively unique among prothrombotic diatheses, in that it clearly predisposes to both arterial and venous events. There is no cure for APS, and current treatments focus on suppressing coagulation, rather than targeting the underlying pathophysiology (3).

Clinically significant aPL recognize both thrombin and beta-2 glycoprotein I (β2GPI), with antibodies to the latter having more uniform clinical testing and the better understood downstream signaling pathways (1). β2GPI, a cationic lipid-binding protein made by liver, endothelial cells, monocytes, and trophoblasts, circulates at high levels in plasma (50–200 μg/ml) (4, 5). While some interesting recent studies have suggested that β2GPI has specific and important roles in innate immunity (6), the function of this abundant plasma protein remains largely unknown.

It has been suggested that anti-β2GPI aPL promote thrombosis by engaging the β2GPI protein on cell surfaces and thereby activating cells, resulting in increased tissue factor expression and release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α (7–9). These processes have been extensively studied in endothelial cells and monocytes, where annexin A2 and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) function as important co-receptors (7–9), and in platelets, where aPL/β2GPI associate with and signal through apoER2 (10). Despite extensive study of the aforementioned cell types, the interaction of aPL with the most abundant leukocyte in human blood, the neutrophil, has only rarely been considered (11–16). The limited studies that do exist suggest that aPL can directly activate neutrophils, as measured by enhanced granule release, oxidative burst, and IL-8 production (11, 12), with possible amplification of this activation by complement C5a (14, 15).

With emerging links between neutrophils and thrombosis in non-autoimmune conditions (17, 18), there is now a compelling reason to further explore aPL/neutrophil interplay. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) release, a form of neutrophil cell death that results in the externalization of decondensed chromatin decorated with granular and nuclear proteins (19), has recently been recognized as an important mediator of pathologic thrombosis. NETs form an integral part of venous thrombi in animals and humans (17, 20), with NET-derived proteases activating the coagulation cascade, and the NET structure serving as scaffolding for clot assembly (21, 22). Activated neutrophils and resultant NETs are also known to damage the endothelium (23, 24), and have been recognized as potential mediators of atherosclerosis and arterial thrombosis (25–27). We therefore sought to determine whether NET release might be a mechanism by which aPL/neutrophil interplay predisposes to thrombotic events in APS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects

Patients were recruited from Rheumatology and Hematology clinics at the University of Michigan or from the Department of Immunology and Rheumatology at the Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán in Mexico City. All patients met the laboratory criteria for APS according to the updated Sydney classification criteria (28). If patients only had thrombocytopenia and/or hemolytic anemia (n=6 patients), they were classified as APS according to the classification criteria of Alarcón-Segovia et al (29). All remaining primary APS patients (n=46) met the full Sydney classification criteria. Importantly, no APS patient in our primary cohort met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (30); the only exceptions were the patients explicitly labeled as having secondary APS in the serum-stimulation experiments. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards from both institutions, and all patients gave their written informed consent.

The Michigan population was predominantly Caucasian (European American) and the Mexico population predominantly Hispanic (Supplementary Table 1). Despite this disparity, we found no difference between the Michigan and Mexico populations in any of the NET/neutrophil assays described in this study (data not shown). Healthy volunteers were recruited by advertisement at the University of Michigan; this control population was predominantly Caucasian (Supplementary Table 1).

Blood was collected by phlebotomist venipuncture into standard serum or 3.2% sodium citrate tubes. Serum and plasma were prepared by standard methods and stored at −80°C until ready for use. Anti-β2GPI IgG, IgM, and IgA, as well as anti-cardiolipin IgG and IgM, were determined with commercially available ELISA kits (Inova Diagnostics) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Lupus anticoagulant (LAC) was determined by a LAC/1 screening reactant and a confirmatory LAC/2 test according to published guidelines (31). Supplementary Table 1 displays the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study.

Reagents

Human monoclonal aPL were a generous gift from Drs. Pojen Chen and Barton Haynes, and have been described previously (32). Monoclonal antibodies and other purified reagents were determined to be free of endotoxin contamination by a chromogenic endotoxin quantification kit (Pierce), performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Other reagents are described within the individual assay protocols below.

Quantification of cell-free DNA and MPO-DNA complexes

Cell-free DNA was quantified in sera and plasma using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MPO-DNA complexes were quantified similarly to what has been previously described (33). This protocol used several reagents from the Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Roche). First, a high-binding EIA/RIA 96-well plate (Costar) was coated overnight at 4°C with anti-human MPO antibody (Bio-Rad, 0400-0002), diluted to a concentration of 5 μg/ml in coating buffer (Cell Death kit). The plate was washed 3 times with wash buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in PBS), and then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 90 minutes at room temperature. The plate was again washed 3 times, before incubating overnight at 4°C with 10% sera or plasma in the aforementioned blocking buffer. The plate was washed 5 times, and then incubated for 90 minutes at room temperature with 1x anti-DNA antibody (HRP-conjugated; Cell Death kit) diluted in blocking buffer. After 5 more washes, the plate was developed with 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Invitrogen) followed by a 2N sulfuric acid stop solution. Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm with a Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek). Data was normalized to an in vitro-prepared NET standard, included on every plate.

Cell isolation

Citrated blood from patients or healthy volunteers was fractionated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare) to separate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from neutrophils. Neutrophils were then further purified by dextran sedimentation of the red blood cell (RBC) layer, before lysing residual RBCs with 0.2% sodium chloride. Neutrophil preparations were 98–99% pure as confirmed by both flow cytometry and nuclear morphology.

Quantification of NETs by immunofluorescence

A protocol similar to what has been described previously was followed (34). Briefly, 1.5 × 105 neutrophils were seeded onto coverslips coated with 0.001% poly-L-lysine (Sigma) and then incubated in RPMI-1640 supplemented with L-glutamine. Experiments were done in the absence of fetal bovine serum or human serum unless explicitly stated otherwise. Neutrophil stimulation was with a variety of reagents including phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA, 20 nM, Sigma), lipopolysaccharide (LPS from E. coli, 100 μg/ml, Sigma), and various human antibodies at 10 μg/ml. Tested inhibitors include diphenyleneiodonium (DPI, 20 μM, Tocris Bioscience), TAK-242 TLR4 inhibitor (5–10 μM, Millipore), anti-TLR2 (10–25 μM, clone T2.5, eBioscience), anti-TLR4 (10–25 μM, HTA125, eBioscience), Polymyxin B (50 μg/ml, Sigma), and anti-CD11b (10 μg/ml, clone M1/70, BioLegend). Stimulation of neutrophils was for 2–3 hours at 37°C. For immunofluorescence-based quantification, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde without permeabilization. DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Protein staining was with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to neutrophil elastase (ab21595, Abcam) and a FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (SouthernBiotech). Images were collected with an Olympus microscope (IX70) and a CoolSNAP HQ2 monochrome camera (Photometrics) with Metamorph Premier software. Image overlays and background correction were with Metamorph, and the recorded images were loaded onto Adobe Photoshop for further analysis. NETs (decondensed extracellular DNA co-staining with neutrophil elastase) were quantified by two blinded observers, and digitally recorded to prevent multiple counts; the percentage of NETs was calculated by averaging 5–10 40x fields per sample. To quantify extracellular DNA, incubation was essentially as above, albeit with 1 × 105 cells/well in 96-well tissue culture black plates with clear bottoms (Costar). After incubation, 1x reagent from the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen) was mixed 1:1 with the culture medium directly in the incubation plate. After 5 minutes at room temperature, fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and an emission wavelength of 520 nm in a Synergy H1 Hybrid Plate Reader (Bio-tek). When visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy, the only demonstrable staining after this short incubation period was of extracellular DNA; no intact nuclear DNA could be visualized. Representative images were captured with an Olympus microscope (IX70) and a CoolSNAP HQ2 monochrome camera (Photometrics) with Metamorph Premier software.

Identification of low-density granulocytes (LDGs)

LDGs were identified and quantified by flow cytometry as previously described (35). Briefly, PBMCs were isolated from citrated blood by density centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque Plus). Residual RBCs were lysed with hypotonic saline, and cells were then resuspended in flow buffer consisting of PBS supplemented with 1% BSA and 1% horse serum. LDGs were identified by their characteristic appearance on forward- and side-scatter plots. LDGs were consistently CD10hi CD14lo CD15hi.

IgG purification

IgG was purified from APS or control sera with a Protein G Agarose Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce). Briefly, serum was diluted in IgG binding buffer and passed through a Protein G Agarose column at least 5 times. IgG was then eluted with 0.1 M glycine and neutralized with 1 M Tris. This was followed by overnight dialysis against PBS at 4°C. IgG purity was verified with Coomassie staining, and concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

F(ab′)2 generation

F(ab′)2 fragments were generated and purified from the total IgG fractions of healthy controls or APS patients with the Pierce F(ab′)2 Preparation Kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Anti-β2GPI depletion with purified β2GPI

High-binding EIA/RIA plates (Costar) were coated overnight at 4°C with 10 μg/ml purified β2GPI (U.S. Biologicals) diluted in coating buffer from the Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Roche). Plates were then washed with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS, and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 3 hours at room temperature. APS total IgG fractions (10 μg/ml) were added to the plates and incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. As a negative control, APS total IgG fractions were added to wells coated with BSA (mock depletion). After overnight incubation, unbound APS IgG was removed from the plates, sterile filtered, and used for stimulation of neutrophils.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed by resuspending in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton-X, and a Roche protease inhibitor cocktail pellet) on ice for 1 hour. After spinning to remove debris, protein concentration was measured with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions, and transferred to a 0.45-micron nitrocellulose membrane. Primary antibodies were directed against β2GPI (A80-142A, Bethyl), annexin A2 (ab178677, Abcam), and β-actin (ab8227, Abcam). Detection was with HRP-conjugated anti-goat or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Western Lightning Plus-ECL (PerkinElmer). Images were captured with an Omega Lum C detector and densitometry was performed using UltraQuant software (Aplegen).

Immunofluorescence

1.5 × 105 neutrophils were seeded onto coverslips coated with 0.001% poly-L-lysine (Sigma) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. In some experiments, cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X for 15 minutes at room temperature. Blocking was with 1% bovine serum albumin. Primary antibodies were to β2GPI (Bethyl) and myeloperoxidase (MPO, Dako, A0398). Appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies were from SouthernBiotech. DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Imaging was with an Olympus microscope (IX70) as above.

Flow cytometry

β2GPI expression on the cell surface of control neutrophils and monocytes was determined by flow cytometry, using a similar protocol as to what has been described previously (4). Freshly isolated control neutrophils and PBMCs were stained with rabbit polyclonal anti-human β2GPI (ABS162, Millipore), as well as anti-human CD10 (Biolegend) as a neutrophil marker or anti-human CD14 (Biolegend) as a monocyte marker. Staining was for 30 minutes at 4°C. After washing, cells were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde before analysis with a CyAn ADP Analyzer (Beckman Coulter). Further data analysis was done in FlowJo.

Quantification of neutrophil H2O2 production

The generation of H2O2 was quantified, essentially as described previously (36). Briefly, H2O2 production was detected by a colorimetric assay, with 50 μM Amplex Red reagent (Invitrogen) and 10 U/ml horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) added to the culture medium. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm and linearity was assured with an H2O2 standard curve. The data was plotted with the no-inhibitor PMA condition set to 100%, after subtracting for background H2O2 production from unstimulated cells.

Thrombin generation assay

Thrombin generation was measured as previously described (37). Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was prepared by centrifugation of citrated blood at 1500 x g for 10 minutes at room temperature. 1 × 105 control neutrophils were added to 35 μL aliquots of PPP from healthy volunteers or patients in wells of a 96-well black Costar plate. Where indicated, PPP was treated with the following enzymes or antibodies before the addition of neutrophils: DNase I (20 μg/mL, Pulmozyme®/dornase alfa, Genentech), HTF-1 (10 μg/mL, murine monoclonal antibody against tissue factor, BD Biosciences), or IgG/APS monoclonal Abs (10 μg/mL). Sample volume was brought to a final volume of 50 μL by the addition of phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

After incubation of neutrophils in plasma for 30 minutes at 37°C, coagulation was initiated by the addition of 50 μL of reaction buffer containing 15 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM Z-Gly-Gly-Arg-AMC (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland). Thrombin generation was then monitored using the Technothrombin TGA thrombin generation assay (Technoclone). Thrombin generation profiles were analyzed using Technothrombin TGA software (Technoclone). Delta (Δ) values were calculated by subtracting the baseline condition (either plasma alone or plasma supplemented with IgG) from the experimental condition of interest (for example, plasma + neutrophils). Plasma samples from patients treated with either warfarin or heparin-based anticoagulants were not included in this analysis.

Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, results are presented as the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). Data analysis was with GraphPad Prism software version 6. Data sets were tested for Gaussian distribution by D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Pairs of data with a Gaussian distribution were analyzed by unpaired t testing, while nonparametric data were assessed by Mann-Whitney test. Correlations were tested by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

Given previous and extensive links between NETs and both human and murine lupus (34, 36, 38–41), we focused on patients with primary APS for the key experiments of this study. All 52 primary APS patients met the Sydney laboratory criteria, while 46 fulfilled both Sydney (28) and Alarcón-Segovia’s classification criteria (29). Four patients had thrombocytopenia and two Evans’ syndrome as their sole clinical manifestation, and therefore only fulfilled Alarcón-Segovia’s clinical criteria (28, 29). Importantly, none of the patients with primary APS met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for SLE (30). The 52 patients had an array of serologic positivity, clinical manifestations, and medication usage, as described in Supplementary Table 1. No patient included in this study had experienced a new thrombotic event in the three months prior to blood collection.

Cell-free DNA and NETs are increased in the circulation of patients with APS

We first measured levels of cell-free DNA and NETs in the plasma of APS patients (n=26). These levels are elevated in other disease processes with a prothrombotic diathesis such as sepsis (37), thrombotic microangiopathy (42), small vessel vasculitis (33), and cancer (43). As compared to healthy controls, we found APS plasma to have increased levels of both cell-free DNA (Figure 1A) and NETs (Figure 1B), with the latter detected by an ELISA for MPO-DNA complexes (33).

Figure 1. Cell-free DNA and NETs are increased in the circulation of patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

A, Cell-free DNA was measured in the plasma of APS patients (n=26) or healthy controls. B, Circulating NETs were measured in the same plasma by MPO-DNA ELISA. C, Cell-free DNA was measured in sera of APS patients (n=52) or healthy controls. D, Correlation between cell-free DNA and circulating NETs (MPO-DNA complexes) in APS sera. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. In addition to the individual data points, mean and standard deviation are also presented in panels A–C.

In general, serum samples contain more cell-free DNA than plasma (44), probably the result of the in vitro clot that forms during serum preparation. Despite this potential background of nonspecific DNA, others have had success measuring NETs in diseased sera, for example in ANCA-associated vasculitis (33). Given our access to more APS sera (n=52) than plasma, we also tested the levels of cell-free DNA and NETs in these samples. Indeed, we found a significant increase in cell-free DNA in APS sera as compared to controls (Figure 1C). Further, cell-free DNA showed a statistically significant correlation with circulating NETs in these samples (Figure 1D), demonstrating that the cell-free DNA is at least partially neutrophil-derived. In summary, APS patients have elevated levels of circulating cell-free DNA and NETs as compared to healthy controls, even between thrombotic episodes, suggesting that their neutrophils are predisposed toward NET release.

Neutrophils from primary APS patients spontaneously release NETs

From a subset of the APS patients, we isolated neutrophils for analysis of NET release. Indeed, APS neutrophils demonstrated enhanced spontaneous NET release as compared to controls (Figure 2A–B). Of note, these neutrophils were isolated by a typical Ficoll protocol (see Materials and Methods) and would therefore be considered of “normal” density. Specifically, they would not meet criteria for the low-density granulocytes (LDGs) that have been described at increased numbers in lupus patients (35), and that are known to undergo exaggerated NET release (34). To be as definitive as possible on this point, we tested primary APS patients for the presence of circulating LDGs. In contrast to lupus patients, LDGs were only detected at low levels in patients with primary APS, similar to healthy controls (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. Primary APS neutrophils demonstrate enhanced NET release.

A, Freshly-isolated neutrophils from healthy controls or APS patients (n=18) were seeded onto coverslips and incubated in serum-free media for 2 hours. NET release was scored by immunofluorescence microscopy. B, Representative immunofluorescence microscopy of control (top) and APS (bottom) neutrophils as presented in panel A. Blue=DNA and green=neutrophil elastase. Scale bars=25 microns. C, Control neutrophils were treated with 10% sera from heterologous healthy controls or APS patients for 2 hours. NET release was scored by immunofluorescence microscopy. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, and ****p<0.0001; ns=not significant. In addition to individual data points, mean and standard deviation are also presented.

The above assay of NET release (Figure 2A–B) was in the absence of specific in vitro stimulation, suggesting that the primary stimulus to NET release was provided in vivo before neutrophil isolation. Indeed, there was a positive correlation between this in vitro NET release, and levels of circulating MPO-DNA complexes in vivo (Supplementary Figure 2). Further arguing that this predisposition toward NET release was determined by circulating factors, we were able to induce NET formation in control neutrophils by incubating with sera from primary APS patients (Figure 2C). We found similar stimulation when treating neutrophils with sera from patients with secondary APS (Figure 2C). The clinical characteristics of these secondary APS patients (all of whom had SLE) are described in Supplementary Table 2. In summary, APS neutrophils are predisposed to release NETs, an effect replicated by incubating control neutrophils with the sera of APS patients.

Anti-β2GPI IgG stimulates neutrophils to release NETs

While it is likely that multiple factors contribute to the ability of APS sera to promote NET release, we were especially interested in whether aPL may play a specific role in the process, a concept supported by the interaction of aPL with other cell types such as monocytes, endothelial cells, and platelets (7, 9, 10), as well as the limited studies to date in neutrophils (11, 12). Indeed, we found a positive correlation between anti-β2GPI IgG and circulating MPO-DNA complexes in APS patients (Supplementary Figure 3A). Further, positive testing for lupus anticoagulant was associated with higher levels of MPO-DNA (Supplementary Figure 3B), as was anti-cardiolipin IgG (Supplementary Figure 3C, although not statistically significant). In contrast, IgM and IgA aPL did not correlate with circulating MPO-DNA (Supplementary Figure 3). Finally, there was a clear trend for higher levels of circulating MPO-DNA in patients who were “triple-positive” for anti-β2GPI, anti-cardiolipin, and lupus anticoagulant, as compared to patients who were double- and single-positive (Supplementary Figure 3E); the difference between triple-positive and single-positive was statistically significant.

Based on the above data, we selected five patients with anti-β2GPI IgG (all triple-positive) and five healthy controls, and isolated their total IgG fractions. The IgG from the APS patients significantly stimulated NET release as compared to the healthy controls (Supplementary Figure 4). This effect was independent of the presence of serum (Supplementary Figure 4), and could be abrogated by specifically depleting the anti-β2GPI fraction (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 5). Further, the stimulation persisted even when the Fc region of APS IgG was removed (Supplementary Figure 6). Specifically, APS F(ab′)2 fragments showed similar activity in NET formation assays as the parent APS IgG (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 3. Anti-β2GPI IgG stimulates neutrophils to release NETs.

A, Five APS IgG samples were pooled, and then depleted of anti-β2GPI IgG using purified β2GPI protein. Control neutrophils were stimulated with IgG (10 ug/ml) as indicated for 3 hours. NET release was scored by immunofluorescence microscopy. B, Control neutrophils were treated with purified monoclonal antiphospholipid Abs (aPL; 10 μg/ml) for 3 hours in the presence or absence of 10% autologous serum. aPL IS4, CL1, and CL24 are known to bind β2GPI, while IS1 and IS2 do not. P values were determined by comparing data sets to control IgG (−/+ serum as appropriate). C, Control neutrophils were stimulated with control IgG, CL1, or 20 nM PMA. After 2 hours, PicoGreen was added to the culture, and fluorescence intensity (corresponding to extracellular DNA) was measured. Normalization was to cells permeablized with 0.1% Triton. In panels A–C, bars represent the mean and SEM of at least five independent experiments; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. D, Representative live cells stained with PicoGreen as in panel C. In the CL1 sample, expanded cell remnants (dashed lines) are surrounded by a halo of DNA (green). Scale bars=25 microns.

To further test whether this effect could be mediated by anti-β2GPI IgG, we utilized several well-characterized human aPL IgG monoclonal antibodies. Two of the antibodies, IS1 and IS2, are known to bind phospholipids in β2GPI-independent fashion (32), and three antibodies, IS4, CL1, and CL24, are β2GPI-dependent antibodies (32). While IS1 and IS2 were associated with minimal stimulation of NET formation, the other three antibodies all promoted significant NET release (Figure 3B). Similar to the total-IgG-fraction experiments above, this effect was independent of human serum (Figure 3B). To gauge the potency of this NET release by another technique, we quantified extracellular DNA with PicoGreen, a relatively cell-impermeable reagent that specifically fluoresces when associated with double-stranded DNA. By this technique we saw similar quantities of externalized DNA when neutrophils were treated with the anti-β2GPI monoclonal CL1, as compared to the well-recognized and robust NET stimulator PMA (Figure 3C). By microscopy, we confirmed that intact, unstimulated neutrophils demonstrated little fluorescence with PicoGreen staining (Figure 3D). In summary, anti-β2GPI antibodies promote NET release, both in total IgG fractions and as human monoclonal antibodies.

β2GPI is detectable on the neutrophil surface

We had originally hypothesized that an exogenous source of β2GPI protein (for example, from human serum) would be necessary for anti-β2GPI-mediated NET release. However, with both APS IgG fractions and anti-β2GPI monoclonals, this was not the case (Supplementary Figure 4 and Figure 3). We therefore asked whether β2GPI protein might be detectable in freshly isolated control neutrophils, as were used for the above stimulation experiments. By western blotting, we were able to detect β2GPI in the purified neutrophils, at a level that was actually higher than what was detected in total peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Figure 4A). This was in contrast to the endothelial cell and monocyte co-receptor for aPL/β2GPI, annexin A2 (9, 45), which was not detectable in neutrophils (Figure 4A). We also characterized neutrophil β2GPI by immunofluorescence microscopy. Punctate β2GPI was detectable on unpermeabilized neutrophils, with no significant change in the staining pattern with detergent (0.1% Triton) permeabilization (Figure 4B). This was in contrast to the cytoplasmic granule protein neutrophil elastase, which was only detectable with permeabilization (Figure 4B). To further confirm this finding, we quantified levels of neutrophil-surface β2GPI by flow cytometry. Indeed, we were able to detect β2GPI on at least 80% of circulating neutrophils (Figure 4C), which was higher than the percentage of β2GPI-positive monocytes, by both our analysis (Figure 4C) and the work of others (4). Further, the percentage of β2GPI-positive neutrophils was not significantly different in APS patients as compared to healthy controls (Supplementary Figure 7). In summary, β2GPI is present on the surface of neutrophils where it can potentially mediate anti-β2GPI binding.

Figure 4. β2GPI is detectable on the neutrophil surface.

A, Neutrophils and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from healthy controls. Total protein extracts were prepared by detergent lysis. Western blotting was to β2GPI, annexin A2, and β-actin. Quantification was by densitometry and is expressed in arbitrary units. Bars represent mean and SEM. N=6, including 3 samples for each group not pictured here; western blotting was repeated twice with similar results. ***p<0.001. B, Neutrophils were isolated from healthy controls and allowed to adhere to coverslips. Cells were then immediately fixed with paraformaldehyde, and in some cases permeabilized with detergent (0.1% Triton). Representative images are shown with β2GPI and neutrophil elastase stained green and DNA stained blue. Scale bars=25 microns. C, Neutrophils and monocytes were identified by forward/side-scatter, and additionally confirmed to be CD10-positive and CD14-positive, respectively. The percentage of β2GPI-positive cells was then determined. Bars represent mean and SEM. N=6 healthy controls for each group; **p<0.01. To the right is a representative neutrophil histogram, demonstrating that the majority of CD10-positive cells are also positive for β2GPI.

aPL-mediated NET release is dependent on reactive oxygen species (ROS), and TLR4

ROS are generated during NET formation, and their blockade has been shown to prevent many (46), but not all (47, 48), forms of NET release. When the aforementioned aPL monoclonals were tested in an H2O2 production assay, a similar pattern was seen as for NET formation, with IS1 and IS2 giving minimal activity, and the other three monoclonals demonstrating robust stimulation (Supplementary Figure 8A). A similar result was seen when control neutrophils were stimulated with the total IgG fractions described above, with APS IgG stimulating more H2O2 production than control IgG (Supplementary Figure 8B). We also investigated whether aPL-mediated NET release could be prevented by an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, and consequently ROS formation. Indeed, treatment with DPI potently inhibited NET release (Supplementary Figure 8C).

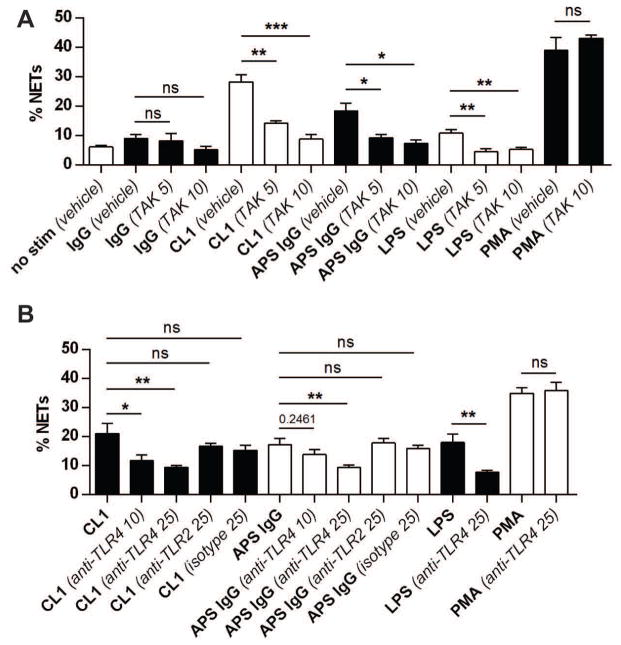

In other cell types, such as monocytes and endothelial cells, TLR4 has been implicated as an important mediator of aPL stimulation (8, 9), while knockout of TLR4 has been shown to protect against APS-like disease in mouse models (49). Further, one study has shown that aPL activation of neutrophils (albeit without testing NET release) can be mediated by TLR4 (12). Here, we found that a chemical TLR4 inhibitor, TAK-242, abrogated both NET formation (Figure 5A) and H2O2 production (Supplementary Figure 9) in response to anti-β2GPI monoclonals as well as total APS IgG fractions. A similar inhibition of NET formation was seen with an anti-TLR4 blocking antibody, but not with anti-TLR2 or isotype control (Figure 5B). All antibodies used for stimulation were free of endotoxin as measured by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay. Further, aPL-mediated stimulation remained effective in the presence of the known endotoxin inhibitor Polymyxin B (Supplementary Figure 10). In summary, both ROS formation and TLR4 engagement are important for aPL-mediated NET release, in contrast to PMA-stimulated NET formation which is TLR4-independent. Also, TLR4 signaling here is not mediated by endotoxin, which would be consistent with the work of others studying the interplay between aPL and TLR4 in monocytes and endothelial cells (8, 9).

Figure 5. aPL-mediated NET release can be blocked by inhibition of TLR4, but not TLR2.

A, Control neutrophils were stimulated with control human IgG, an anti-β2GPI monoclonal (CL1), or pooled IgG from 5 APS patients (all 10 μg/ml) for 3 hours. Control treatments were with LPS (100 ng/ml) and PMA (20 nM). Some samples were pretreated with TAK-242, a TLR4 inhibitor, at 5 or 10 μM. NET release was scored by immunofluorescence microscopy. B, Control neutrophils were stimulated as indicated (concentrations as in panel A) for 3 hours. Some samples were pretreated with anti-TLR4, anti-TLR2, or isotype (10 and 25 μM). NET release was scored by immunofluorescence microscopy. For all panels, bars represent mean and SEM; n=5 independent experiments per condition. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and ns=not significant.

Other groups have shown that when neutrophils are cultured in vitro on poly-lysine-coated coverslips (as was done for many of the stimulation experiments here), beta-2 integrin engagement is an important part of achieving full neutrophil activation and NET release (50). Indeed, blockade of the beta-2 integrin Mac-1 with an anti-CD11b monoclonal antibody prevented NET release in response to not just aPL, but also PMA (Supplementary Figure 11). This result emphasizes that parallel pathways may be necessary to achieve full activation, and suggests that homo- and heterotypic cellular interactions should be carefully considered when aPL/neutrophil interplay begins to be studied in vivo.

Purified aPL, as well as APS patient plasma, enhance thrombin generation in neutrophil- and DNA-dependent fashion

The above findings are especially important when considered in the context of the arterial and venous thrombotic events that affect APS patients. To ask whether aPL-mediated NET release has prothrombotic potential, we utilized a thrombin generation assay (37). We first found that thrombin generation is enhanced when control plasma supplemented with anti-β2GPI monoclonals is incubated with control neutrophils (see Figure 6A for representative data for CL1, and Figure 6B for representative numerical data for the three anti-β2GPI monoclonals known to stimulate NET release). Importantly, neutrophil-mediated thrombin generation could be attenuated by treatment with recombinant human DNase (Figure 6A–B), strongly arguing that the effect is dependent on NET formation and not upregulation of surface molecules such as tissue factor. Similarly, the addition of APS total IgG fractions to control plasma resulted in enhanced thrombin generation, which could also be abrogated by DNase treatment (Figure 6C and Supplementary Figure 12A).

Figure 6. Purified aPL, as well as APS patient plasma, stimulate thrombin generation in neutrophil- and DNA-dependent fashion.

A, Representative thrombin (IIa) generation plot demonstrating enhanced generation when neutrophils are exposed to platelet-poor plasma (from a healthy control) supplemented with aPL CL1 (10 μg/ml). The effect is not seen with plasma alone or plasma supplemented with control IgG. The effect is disrupted by DNase treatment. B, Representative data demonstrating that control plasma supplemented with anti-β2GPI monoclonals promotes neutrophil-mediated thrombin generation. Delta (Δ) values were calculated relative to the baseline condition (in this case, plasma supplement with IgG, but not neutrophils). These data are representative of 3 experiments, all with similar results. C, Control plasma was separately supplemented with total IgG (10 μg/ml) isolated from 5 healthy controls or 5 primary APS patients with anti-β2GPI IgG positivity. Plasma was then mixed with control neutrophils alone or neutrophils + DNase, and thrombin generation was determined. D, Plasma from healthy controls or primary APS patients was mixed with control neutrophils alone or neutrophils + DNase, and thrombin generation was determined. In panels C and D, mean and standard deviation are presented; *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. Each data point is the average of 3 independent assays.

We were also interested in assessing APS patient plasma for its effects on neutrophil-dependent thrombin generation. When APS patients were under treatment with warfarin, their plasma uniformly failed to generate thrombin in the presence of neutrophils (Supplementary Figure 13), presumably secondary to the depletion of thrombin and other vitamin K-dependent factors in this context. This absence of thrombin generation was despite NET release being active in these samples (data not shown). We were able to identify eight APS plasmas that had been isolated from patients not under treatment with either warfarin or a heparin-based anticoagulant. Four of these patients had anti-β2GPI IgG, while seven had anti-cardiolipin IgG. Similar to the aPL-supplemented control plasmas (Figure 6A–C), APS patient plasma was a significant trigger of NET-mediated thrombin generation (Figure 6D and Supplementary Figure 12B), an effect that could again be abrogated by DNase treatment. Importantly, DNase treatment in the absence of neutrophils had no effect on baseline thrombin generation (data not shown). In summary, aPL stimulate neutrophils to release NETs, which then promote thrombin generation. In this model, thrombin generation can be prevented by either DNase treatment or depletion of clotting factors with warfarin.

Circulating NETs correlate with a history of arterial thrombosis

As discussed above, circulating NET levels correlated with both anti-β2GPI IgG levels and the presence of a lupus anticoagulant phenotype (Supplementary Figure 3). Here, we asked whether circulating NETs and NET release could be predicted by clinical variables including history of specific events (Supplementary Table 3) and medications (Supplementary Table 4). Indeed, we found a positive correlation between history of arterial thrombosis and circulating cell-free DNA/NETs (p=0.04, Supplementary Table 3). While other trends existed (for example, less circulating NETs in patients with a history of pregnancy morbidity), no other correlation reached statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

We have shown for the first time that neutrophils from patients with APS are predisposed to exaggerated NET release. This effect seems to predominantly depend on circulating aPL, as both purified IgG fractions and anti-β2GPI monoclonals can promote NET release. Somewhat surprisingly, we found that the stimulation was not dependent on the addition of an exogenous source of β2GPI (either in serum or as a purified protein). This is likely explained by the presence of β2GPI on the surface of freshly-isolated neutrophils. Whether β2GPI is made by neutrophils or simply acquired in circulation is unknown, although its presence on the neutrophil surface is not explained by upregulation of phosphatidylserine, as isolated neutrophils were consistently negative for detectable annexin V binding (data not shown). Similarly, we did not find the monocyte/endothelial receptor for β2GPI, annexin A2, on the neutrophil surface.

We found a positive correlation in APS patients between circulating levels of NETs and both anti-β2GPI IgG and lupus anticoagulant positivity (as well as triple-positivity). This was despite all patient samples having been collected outside of acute thrombotic episodes. We speculate that NET levels would increase even further at the time of APS-related events, as is known to happen in the general population for arterial disease (25), DVT (17), and microscopic thrombosis (42). Confirmation of this in APS will require longitudinal investigation. While our in vitro work strongly supports a role for aPL in directly promoting NET release, the higher levels of circulating NETs may also be partially explained by a recent study demonstrating an impaired ability of APS sera to degrade NETs in vitro (16), replicating a phenotype first described in SLE (38). That study did not, however, measure circulating NET levels, nor was the interaction between intact neutrophils and aPL assessed (16).

A compelling and unusual feature of APS is that it predisposes to both arterial and venous thrombosis; this is in contrast to most thrombotic risk factors which promote one or the other. As mentioned above, NETs themselves have also been associated with arterial (25–27, 51), as well as venous (17, 20), events. Additionally, there is emerging evidence of an important role for NETs in cancer-associated thrombosis (43), another disease process associated with both arterial and venous vascular disease (52). Whether aPL/neutrophil interplay plays a role in APS pregnancy morbidity is unknown, although it is interesting to note that exaggerated NET release has been seen in non-autoimmune patients with preeclampsia (53). NETs have also been linked to thrombotic microangiopathy, for example in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (42), a process that replicates many features of the catastrophic form of APS. Although this study was not designed or powered to comprehensively study clinical correlations, we did interestingly find an association between history of arterial events and circulating NETs. This finding awaits confirmation in larger and independent cohorts.

Mechanistically, aPL-mediated NET release is dependent on the production of reactive oxygen species. Such dependence has been seen in most (46), but not all (47, 48), forms of NET release. This could have implications for the interplay between oxidative stress, neutrophils, and aPL, with oxidative stress having previously been shown to be a risk factor for modifications of β2GPI that promote aPL/β2GPI interaction (54). We additionally found that aPL activation of neutrophils was at least partially dependent on TLR4. Numerous studies have shown TLR4 signaling to be important for aPL activation of both monocytes and endothelial cells (8, 9), while TLR4 mutation protects against APS-like disease in animals (49). Indeed, our demonstration of this pathway in neutrophils is complementary to previous work showing synergy between LPS and aPL in neutrophil activation (12). As infections are well recognized to upregulate neutrophil TLR4 (55), one can envision a scenario where NET release smolders at a low level in patients between events, before being dramatically activated in the setting of an infection (two-hit hypothesis).

To fully understand these pathways, NET release will need to be studied in vivo using experimental models of APS. For example, aPL have been shown to indirectly activate neutrophils through the complement cascade and the well-recognized neutrophil stimulator C5a (14, 15). Here, we believe that in vitro aPL-mediated NET release is independent of C5a, as neither total IgG fractions, nor anti-β2GPI monoclonals, were dependent on the presence of serum (and exogenous complement) for neutrophil activation. Further, APS patient sera promoted NET release even when heat-inactivated (data not shown). However, with the recognition that phagocytes themselves may generate and activate some complement components (56), we cannot completely rule out some type of auto-amplification loop here.

We believe this data has implications for the prothrombotic diathesis inherent to APS. aPL-stimulated neutrophils promote thrombin generation, an effect that could be attenuated by DNase treatment, but not treatment with an anti-tissue factor antibody. We also found that plasma isolated from APS patients under treated with warfarin generated no detectable thrombin, despite still promoting NET release. Similarly, heparin can dismantle NETs (17), and prevent NET/histone-mediated platelet activation (57). We therefore postulate that these traditional APS treatments function downstream of NET release.

Regarding other therapies, aspirin, which already has a role as an adjuvant agent in APS when arterial manifestations are present, has been shown to prevent NET release (58). Antimalarial medications also have a role in both the criteria and noncriteria manifestations of APS (3). With evidence that antimalarials interact with, and modulate cellular responses to, extrinsic DNA (59), one wonders if their protective role in APS may be partially attributed to their interaction with NETs. In terms of novel therapeutics, peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) inhibitors, which prevent NET release, have shown therapeutic benefits in murine SLE (36), atherosclerosis (27), and inflammatory arthritis (60), although have yet to be tested in APS. Further, DNase has a protective role in animals in both arterial (stroke, myocardial infarction) (61), and venous models (20). Whether exogenous DNase will ever be a practical means of disrupting circulating NETs is unclear, although Fc fusion proteins have been described (62).

Overall, this study clearly demonstrates that aPL can activate neutrophils to release NETs and hints that these circulating NETs contribute to thrombotic events. NET release should be further assessed in experimental models, with an eye toward more targeted approaches to the therapy of APS patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Pojen Chen and Barton Haynes for the generous gift of monoclonal antiphospholipid antibodies. JSK was supported by NIH K08AR066569, a Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award, and a career development award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no competing interests or conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Andreoli L, Atsumi T, Chighizola CB, Forastiero R, et al. Autoimmunity reviews; 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Task Force. Report on antiphospholipid syndrome laboratory diagnostics and trends; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes GR. Hughes’ syndrome: the antiphospholipid syndrome. A historical view. Lupus. 1998;7 (Suppl 2):S1–4. doi: 10.1177/096120339800700201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erkan D, Aguiar CL, Andrade D, Cohen H, Cuadrado MJ, Danowski A, et al. 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies: task force report on antiphospholipid syndrome treatment trends. Autoimmunity reviews. 2014;13(6):685–96. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conti F, Sorice M, Circella A, Alessandri C, Pittoni V, Caronti B, et al. Beta-2-glycoprotein I expression on monocytes is increased in anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome and correlates with tissue factor expression. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2003;132(3):509–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02180.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caronti B, Calderaro C, Alessandri C, Conti F, Tinghino R, Palladini G, et al. Beta2-glycoprotein I (beta2-GPI) mRNA is expressed by several cell types involved in anti-phospholipid syndrome-related tissue damage. Clinical and experimental immunology. 1999;115(1):214–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agar C, de Groot PG, Morgelin M, Monk SD, van Os G, Levels JH, et al. beta(2)-glycoprotein I: a novel component of innate immunity. Blood. 2011;117(25):6939–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma K, Simantov R, Zhang JC, Silverstein R, Hajjar KA, McCrae KR. High affinity binding of beta 2-glycoprotein I to human endothelial cells is mediated by annexin II. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(20):15541–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen KL, Fonseca FV, Betapudi V, Willard B, Zhang J, McCrae KR. A novel pathway for human endothelial cell activation by antiphospholipid/anti-beta2 glycoprotein I antibodies. Blood. 2012;119(3):884–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorice M, Longo A, Capozzi A, Garofalo T, Misasi R, Alessandri C, et al. Anti-beta2-glycoprotein I antibodies induce monocyte release of tumor necrosis factor alpha and tissue factor by signal transduction pathways involving lipid rafts. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2687–97. doi: 10.1002/art.22802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutters BC, Derksen RH, Tekelenburg WL, Lenting PJ, Arnout J, de Groot PG. Dimers of beta 2-glycoprotein I increase platelet deposition to collagen via interaction with phospholipids and the apolipoprotein E receptor 2′. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(36):33831–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arvieux J, Jacob MC, Roussel B, Bensa JC, Colomb MG. Neutrophil activation by anti-beta 2 glycoprotein I monoclonal antibodies via Fc gamma receptor II. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1995;57(3):387–94. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gladigau G, Haselmayer P, Scharrer I, Munder M, Prinz N, Lackner K, et al. A role for Toll-like receptor mediated signals in neutrophils in the pathogenesis of the anti-phospholipid syndrome. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e42176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redecha P, Franzke CW, Ruf W, Mackman N, Girardi G. Neutrophil activation by the tissue factor/Factor VIIa/PAR2 axis mediates fetal death in a mouse model of antiphospholipid syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(10):3453–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI36089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritis K, Doumas M, Mastellos D, Micheli A, Giaglis S, Magotti P, et al. A novel C5a receptor-tissue factor cross-talk in neutrophils links innate immunity to coagulation pathways. Journal of immunology. 2006;177(7):4794–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girardi G, Berman J, Redecha P, Spruce L, Thurman JM, Kraus D, et al. Complement C5a receptors and neutrophils mediate fetal injury in the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(11):1644–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI18817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leffler J, Stojanovich L, Shoenfeld Y, Bogdanovic G, Hesselstrand R, Blom AM. Degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps is decreased in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(1):66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, Schatzberg D, Monestier M, Myers DD, Jr, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(36):15880–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) impact on deep vein thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(8):1777–83. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, Thomas GM, Martinod K, De Meyer SF, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote deep vein thrombosis in mice. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2012;10(1):136–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, Manukyan D, Pfeiler S, Goosmann C, et al. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nature medicine. 2010;16(8):887–96. doi: 10.1038/nm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Bruhl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, Chandraratne S, Konrad I, Lorenz M, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209(4):819–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta AK, Joshi MB, Philippova M, Erne P, Hasler P, Hahn S, et al. Activated endothelial cells induce neutrophil extracellular traps and are susceptible to NETosis-mediated cell death. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(14):3193–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmona-Rivera C, Zhao W, Yalavarthi S, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus through the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borissoff JI, Joosen IA, Versteylen MO, Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, et al. Elevated levels of circulating DNA and chromatin are independently associated with severe coronary atherosclerosis and a prothrombotic state. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(8):2032–40. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doring Y, Manthey HD, Drechsler M, Lievens D, Megens RT, Soehnlein O, et al. Auto-antigenic protein-DNA complexes stimulate plasmacytoid dendritic cells to promote atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2012;125(13):1673–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.046755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knight JS, Luo W, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Subramanian V, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition reduces vascular damage and modulates innate immune responses in murine models of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2014;114(6):947–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2006;4(2):295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alarcón-Segovia D, Delezé M, Oria CV, Sánchez-Guerrero J, Gómez-Pacheco L, Cabiedes J, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies and the antiphospholipid syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus. A prospective analysis of 500 consecutive patients. Medicine. 1989;68:353–65. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25(11):1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pengo V, Tripodi A, Reber G, Rand JH, Ortel TL, Galli M, et al. Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2009;7(10):1737–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu M, Olee T, Le DT, Roubey RA, Hahn BH, Woods VL, Jr, et al. Characterization of IgG monoclonal anti-cardiolipin/anti-beta2GP1 antibodies from two patients with antiphospholipid syndrome reveals three species of antibodies. British journal of haematology. 1999;105(1):102–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schonermarck U, Back W, Gross WL, Werb Z, et al. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nature medicine. 2009;15(6):623–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, Hodgin JB, Khandpur R, Lin AM, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of immunology. 2011;187(1):538–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denny MF, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Thacker SG, Anderson M, Sandy AR, et al. A distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils isolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induces vascular damage and synthesizes type I IFNs. Journal of immunology. 2010;184(6):3284–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight JS, Zhao W, Luo W, Subramanian V, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition is immunomodulatory and vasculoprotective in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(7):2981–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI67390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould TJ, Vu TT, Swystun LL, Dwivedi DJ, Mai SH, Weitz JI, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent and platelet-independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(9):1977–84. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hakkim A, Furnrohr BG, Amann K, Laube B, Abed UA, Brinkmann V, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(21):9813–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, Frasca L, Conrad C, Gregorio J, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science translational medicine. 2011;3(73):73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, Connolly J, Allantaz F, Xu Z, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Science translational medicine. 2011;3(73):73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell AM, Kashgarian M, Shlomchik MJ. NADPH oxidase inhibits the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Science translational medicine. 2012;4(157):157ra41. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fuchs TA, Kremer Hovinga JA, Schatzberg D, Wagner DD, Lammle B. Circulating DNA and myeloperoxidase indicate disease activity in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies. Blood. 2012;120(6):1157–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-412197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Demers M, Krause DS, Schatzberg D, Martinod K, Voorhees JR, Fuchs TA, et al. Cancers predispose neutrophils to release extracellular DNA traps that contribute to cancer-associated thrombosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(32):13076–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200419109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee TH, Montalvo L, Chrebtow V, Busch MP. Quantitation of genomic DNA in plasma and serum samples: higher concentrations of genomic DNA found in serum than in plasma. Transfusion. 2001;41(2):276–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41020276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, McCrae KR. Annexin A2 mediates endothelial cell activation by antiphospholipid/anti-beta2 glycoprotein I antibodies. Blood. 2005;105(5):1964–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Remijsen Q, Vanden Berghe T, Wirawan E, Asselbergh B, Parthoens E, De Rycke R, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap cell death requires both autophagy and superoxide generation. Cell research. 2011;21(2):290–304. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pilsczek FH, Salina D, Poon KK, Fahey C, Yipp BG, Sibley CD, et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of immunology. 2010;185(12):7413–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byrd AS, O’Brien XM, Johnson CM, Lavigne LM, Reichner JS. An extracellular matrix-based mechanism of rapid neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Candida albicans. Journal of immunology. 2013;190(8):4136–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pierangeli SS, Vega-Ostertag ME, Raschi E, Liu X, Romay-Penabad Z, De Micheli V, et al. Toll-like receptor and antiphospholipid mediated thrombosis: in vivo studies. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2007;66(10):1327–33. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neeli I, Dwivedi N, Khan S, Radic M. Regulation of extracellular chromatin release from neutrophils. Journal of innate immunity. 2009;1(3):194–201. doi: 10.1159/000206974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Megens RT, Vijayan S, Lievens D, Doring Y, van Zandvoort MA, Grommes J, et al. Presence of luminal neutrophil extracellular traps in atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(3):597–8. doi: 10.1160/TH11-09-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Demers M, Wagner DD. NETosis: a new factor in tumor progression and cancer-associated thrombosis. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2014;40(3):277–83. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1370765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta AK, Hasler P, Holzgreve W, Gebhardt S, Hahn S. Induction of neutrophil extracellular DNA lattices by placental microparticles and IL-8 and their presence in preeclampsia. Human immunology. 2005;66(11):1146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Passam FH, Giannakopoulos B, Mirarabshahi P, Krilis SA. Molecular pathophysiology of the antiphospholipid syndrome: the role of oxidative post-translational modification of beta 2 glycoprotein I. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2011;9 (Suppl 1):275–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prince LR, Whyte MK, Sabroe I, Parker LC. The role of TLRs in neutrophil activation. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2011;11(4):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huber-Lang M, Younkin EM, Sarma JV, Riedemann N, McGuire SR, Lu KT, et al. Generation of C5a by phagocytic cells. The American journal of pathology. 2002;161(5):1849–59. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64461-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fuchs TA, Bhandari AA, Wagner DD. Histones induce rapid and profound thrombocytopenia in mice. Blood. 2011;118(13):3708–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lapponi MJ, Carestia A, Landoni VI, Rivadeneyra L, Etulain J, Negrotto S, et al. Regulation of neutrophil extracellular trap formation by anti-inflammatory drugs. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2013;345(3):430–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.202879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuznik A, Bencina M, Svajger U, Jeras M, Rozman B, Jerala R. Mechanism of endosomal TLR inhibition by antimalarial drugs and imidazoquinolines. Journal of immunology. 2011;186(8):4794–804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willis VC, Gizinski AM, Banda NK, Causey CP, Knuckley B, Cordova KN, et al. N-alpha-benzoyl-N5-(2-chloro-1-iminoethyl)-L-ornithine amide, a protein arginine deiminase inhibitor, reduces the severity of murine collagen-induced arthritis. Journal of immunology. 2011;186(7):4396–404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Meyer SF, Suidan GL, Fuchs TA, Monestier M, Wagner DD. Extracellular chromatin is an important mediator of ischemic stroke in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(8):1884–91. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.250993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dwyer MA, Huang AJ, Pan CQ, Lazarus RA. Expression and characterization of a DNase I-Fc fusion enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(14):9738–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.