Abstract

Objective

Pain is not always correlated with radiographic osteoarthritis (OA) severity possibly because people modify activities to manage symptoms. Measures of symptoms that consider pain in the context of activity level may therefore provide greater discrimination than pain alone. Our objective was to compare discrimination of a measure of pain alone with combined measures of pain relative to physical activity across radiographic OA levels.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of the Osteoarthritis Initiative accelerometer substudy, including those with and without knee OA. Two composite pain and activity knee symptom (PAKS) scores were calculated as Western Ontario and McMaster (WOMAC) Universities Osteoarthritis Pain Scale plus one divided by physical activity measures (step and activity counts). Symptom score discrimination across Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) grades were evaluated using histograms and quantile regression.

Results

1806 participants, mean age 65.1 (9.1) years, mean BMI 28.4 (4.8) kg/m2, and 55.6% female, were included. WOMAC, but not PAKS scores, exhibited a floor effect. Adjusted median WOMAC by KL grades 0 – 4 were 0, 0, 1, 1, and 3 respectively. Median PAKS1 and PAKS2 were 24.9, 26.0, 32.4, 46.1, 97.9, and 7.2, 7.2, 9.2, 12.9, 23.8, respectively. PAKS scores had more statistically significant comparisons between KL grades compared with WOMAC.

Conclusions

Symptom assessments incorporating pain and physical activity did not exhibit a floor effect and were better able to discriminate radiographic severity than pain alone, particularly in milder disease. Pain in the context of physical activity level should be used to assess knee OA symptoms.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, and a major public health problem. Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), the prevalence of radiographic knee OA was 37.4% in adults over the age of 60 between 1991 – 1994 in the United States1. With the prevalence of obesity within the United States exceeding 30%, a potent risk factor for OA2, the prevalence of knee OA is only expected to increase.

Historically, it has been asserted knee pain related to OA does not always correlate well with radiographic severity3–5. This perception is primarily based on the absence of a universally positive pain score in those with radiographic OA. A landmark article by Lawrence et al6 cited discordance between radiographic evidence of OA using a dichotomous assessment of pain. In that study, because half of those with the worst radiographic severity did not complain of frequent pain, it was concluded that OA is a predisposing factor for symptoms, not a cause for symptoms6. Paradoxically, the same investigators demonstrated that those with the greatest radiographic OA severity were 10 times more likely to have knee pain compared to those without radiographic OA6.

OA related pain is often activity related7. As a result, people with OA may avoid activities that precipitate the pain as a strategy to manage their pain8. This may explain why in a Canadian observational study of moderate to severe hip and knee OA, 24% of participants had significant improvement of knee pain without commensurate improvement in radiographic severity or joint range of motion9,10. For this reason, measuring pain outcomes as the primary measurement of symptoms in knee OA may be problematic on many levels; without consideration of the patient’s level of physical activity, evaluation of pain may be a poor reflection of a person’s disease severity.

Based on these observations, we propose a more appropriate measure of OA symptom severity would be one that reflects the amount of pain a person experiences in the context of their physical activity level. Accelerometers and pedometers can easily quantify physical activity in the form of activity and step counts. They are widely available, easy to use, affordable, and can provide a measurement of activity over the course of a day.

We hypothesized that symptom assessment accounting for pain in the context of physical activity level would improve discrimination across OA radiographic severity levels compared to pain alone. Therefore, the objective of this study is to compare discrimination of pain alone and combined measures of pain in the context of physical activity across radiographic severity levels within the Osteoarthritis Initiative, an observational study of OA.

Methods

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional study nested within the Osteoarthritis Initiative, a prospective multi-center observational study of knee OA of 4,796 participants, which is comprised of three groups, the progression (N = 1,389), the incidence (N = 3,285), and a non-exposed control group (N = 122). The “progression subcohort” all have pre-existent symptomatic radiographic knee OA (ROA), the “incident subcohort” are at high risk for symptomatic (ROA), and the “non-exposed control subcohort” do not have nor are at high risk for symptomatic ROA. Participants were men and women ages 45 to 79 years old at the time of enrollment at one of four clinical sites, Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island (Pawtucket, RI,) Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio), University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA), and University of Maryland / Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD).

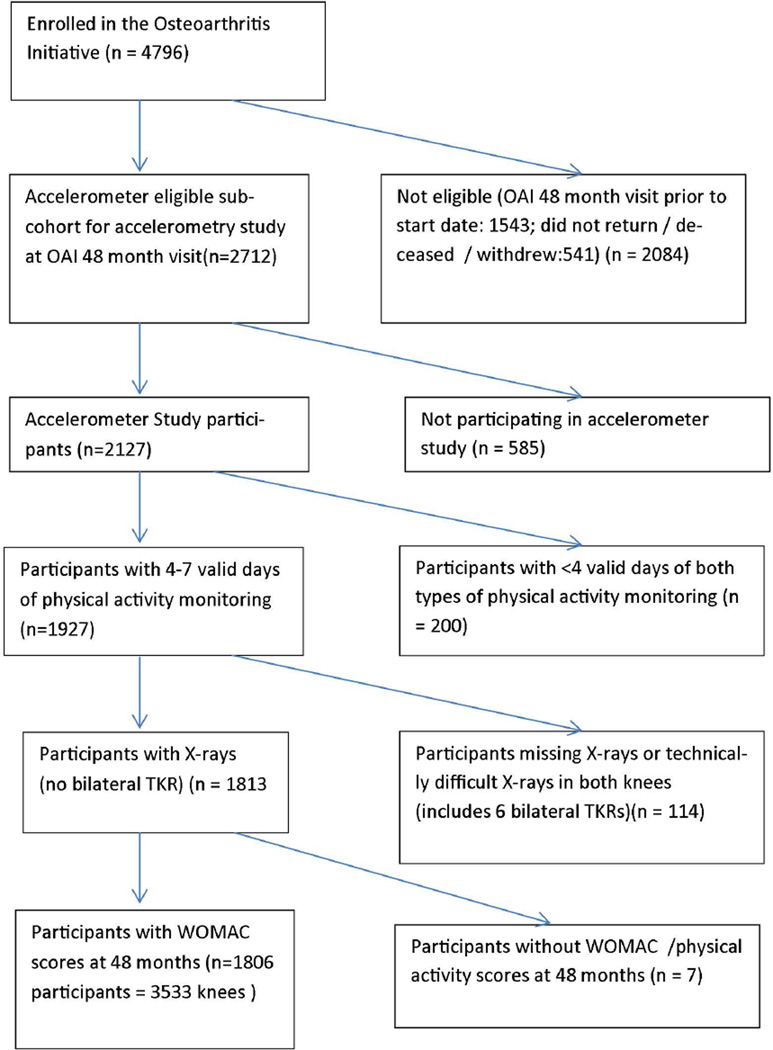

The study population was drawn from 2127 persons enrolled in an Osteoarthritis Initiative accelerometer monitoring substudy, including people from all 3 subcohorts of the OAI, at the 48 month follow-up visit (between August 2008 and July 2010)11 (see figure 1). We studied participants with ≥ 4 days accelerometer monitoring, knee-specific pain data, and knee x-ray readings from the 48-month visit. Approval was obtained from the institutional review board at each Osteoarthritis Initiative site and at Northwestern University. Each participant provided written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing derivation of the sample used for this study.

Pain Assessment

At the 48-month visit, participants were asked to self-report knee-specific pain in reference to the last 7 days by completing the Western Ontario and McMaster (WOMAC) Universities Osteoarthritis Pain Scale (3.1 Likert version)12,13 separately for each knee. The scale assesses pain severity with five activities: pain with walking, taking stairs, standing, in bed, and lying down or sitting. Possible pain scores range from 0 (no pain) to 20 (severe pain). This is an FDA approved measure of knee pain and the most commonly used symptom assessment in knee OA observational studies and clinical trials14.

A visual analog scale assessment of knee specific symptoms was also assessed at the 48 month visit, using the question “Please rate the pain that you’ve had in your right/left knee during the past 30 days by pointing to the number that describes the pain at its worst. “0” means “No pain” and “10” means “Pain as bad as you can imagine.” These data are publicly available on the OAI website (http://oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelease/) under filename AllClinical06_SAS (Version 6.2.2).

Accelerometer Data

We measured activity and step count using a uniaxial GT1M Actigraph accelerometer, a validated instrument in knee OA (correlation with metabolic equivalent r=0.93; with total energy expenditure r=0.93)15. Participants received scripted instructions and were asked to provide 7 days of continuous accelerometer monitoring during waking hours (except during water activities) following the 48-month visit. Trained research personnel initialized each accelerometer and gave in-person instruction on how to position and wear it. The accelerometer was worn on a belt at the natural waistline in line with the right axilla. Step count was output by Actigraph estimation of actual steps from accelerometer output. Activity count was a weighted sum of the number of accelerations/min; weights were proportional to acceleration magnitude. Non-wear periods were identified by periods of ≥90 minutes with 0 counts, allowing for 2 minute interruptions (counts<100). A valid day of accelerometer/step count monitoring was defined as ≥10 wear hours/day.

Knee Radiographs

Weight-bearing, fixed-flexion, posterior-anterior knee radiographs were obtained at the 48-month visit. Central readers (at the Boston University Clinical Epidemiology Research and Training Unit)16 scored these for overall radiographic severity using Kellgren-Lawrence grades (0 – 4) using the Osteoarthritis Research Society International Atlas17. These data are publicly available on the Osteoarthritis Initiative website (http://oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelease/), filename kXR_SQ_BU06_SAS (Version 6.3)). The reliability for these readings (read-reread) was substantial18 (weighted kappa [intra-rater reliability] = 0.71 [95%CI 0.55 – 0.87])19.

Combined Activity and Knee Pain Score Definitions

Two composite pain and activity knee scores (PAKS) were calculated as the ratio of pain divided by physical activity measure. One unit was added to the WOMAC pain score to avoid division of zeros and the PAKS measures were multiplied by 100,000 and 1,000,000 respectively to help scale the values towards the range of 0 – 100.

PAKS1 = ((WOMAC Pain + 1) / daily step count)*100,000)

PAKS2 = ((WOMAC Pain + 1) / daily activity count)*1,000,000)

Higher PAKS values reflect greater symptoms (e.g. poorer clinical status), consistent with less activity and/or greater pain. For example, if two people have identical pain, but different activity levels, the person with less activity will have higher PAKS scores, or a poorer clinical status.

Covariates

Sex was self-reported. Date of birth from OAI baseline visit was used to calculate participant ages at the OAI 48 month follow up visit. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2) as measured at the 48 month OAI visit. If BMI information was missing at the 48 month visit, BMI from the 36 month visit was used instead (n= 5, 0.3%). Participants were classified using the biologic categories of normal weight (BMI 18.5 – 24.9), overweight (BMI 25.0 – 29.9), or obese (BMI≥30).

Statistical Analysis

WOMAC pain score and PAKS scores were evaluated for score discrimination by Kellgren and Lawrence grades using stratified histograms and quantile regression analyses. The analysis sample was composed of participants having paired radiographic and pain data on at least one knee; excluded from analyses are knees with total knee replacement done at or before the OAI 48-month visit. For graphical purposes, one knee per person was used; the right knee was arbitrarily selected irrespective of which knee was more symptomatic. Quantile (median) regression knee-level analyses incorporating data from all knees (e.g. maximally 2 knees per person) used Kellgren and Lawrence grade 0 knees as the referent group. Adjusted analyses included covariates: age at the 48 month visit, sex, and BMI groups (normal, overweight, and obese). Quantile regression analyses with robust, clustered standard errors to account bilateral data from some individuals were performed using Stata/SE (version 13.1, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All other analyses were completed in SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We also performed sensitivity analyses using the visual analog scale instead of WOMAC pain for the quantile regression analyses.

Results

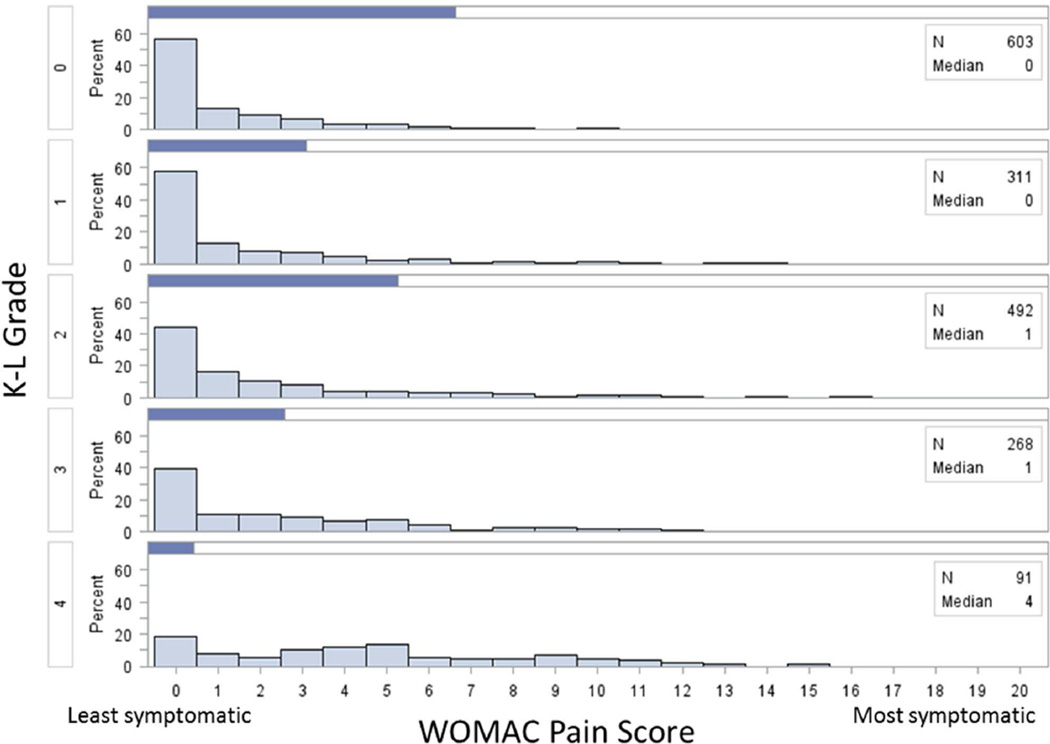

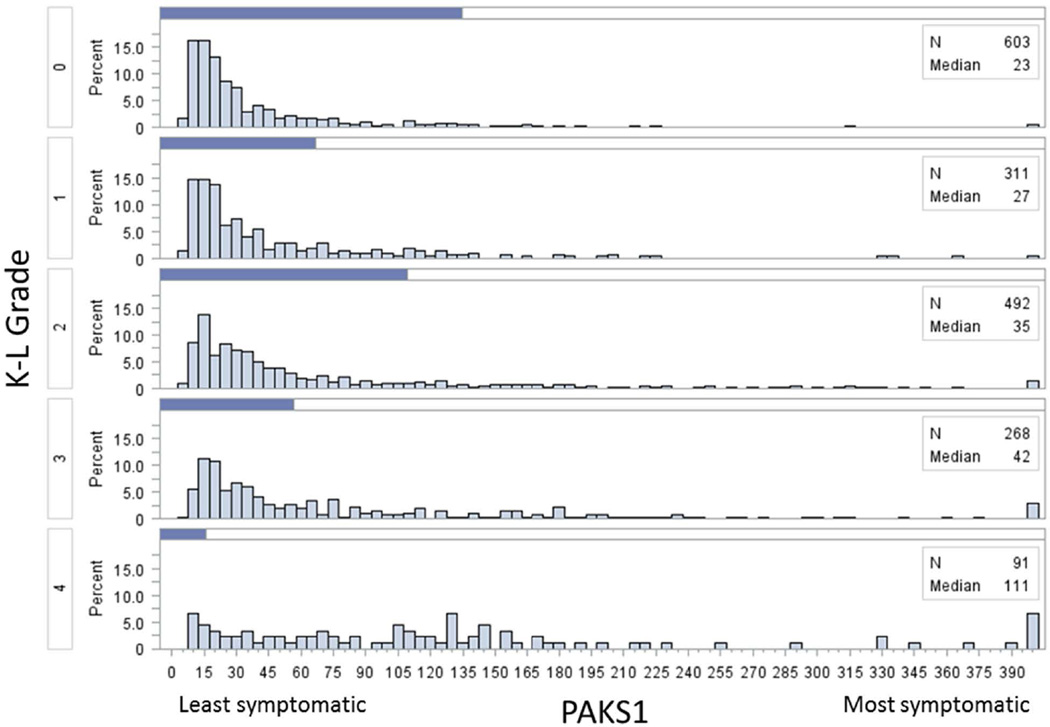

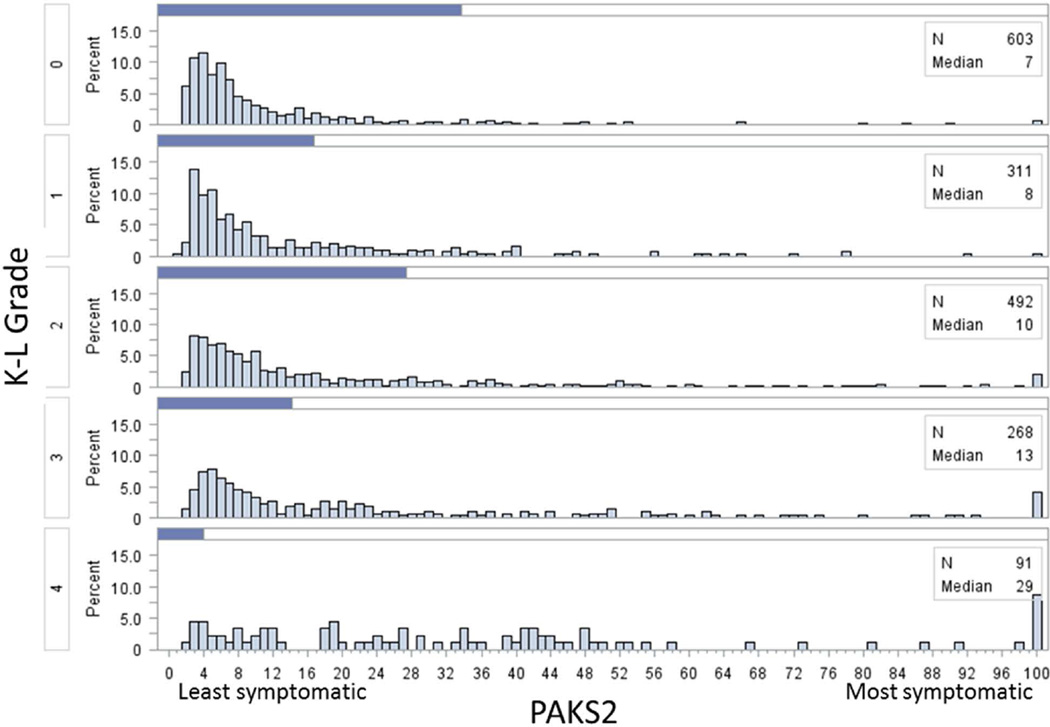

Of the 4796 participants in the OAI, 1806 were participants of this study. For those who were included and excluded from this study, baseline demographics were similar (Table 1). WOMAC pain score exhibited a floor effect (figure 2) while for the PAKS scores, although the scores were skewed to the left, no floor effect was observed. For each progressive increase in Kellgren and Lawrence grade, there was an increase in the median of both PAKS scores (figures 3 and 4).

Table 1.

Comparison of participants included v. excluded from the study.

| Included participants (n=1806 participants) |

Excluded participants (n=2007* participants) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (sd) | 65.1 (9.1) | 65.0 (9.1) |

| Female % (n) | 55.5 (1003) | 59.2 (1189) |

| BMI, mean (sd) | 28.4 (4.8) | 28.8 (5.1) |

| Number of prosthetics**, % (n) | ||

| 0 | 96.4 (1741) | 95.0 (1689) |

| 1 | 3.6 (65) | 4.9 (87) |

| 2 | 0.0 (0) | 0.1 (2) |

| Maximal K/L grade***, % (n) | ||

| 0 | 23.0 (415) | 27.0 (479) |

| 1 | 16.2 (292) | 13.3 (236) |

| 2 | 31.5 (569) | 28.7 (510) |

| 3 | 20.5 (370) | 20.6 (365) |

| 4 | 8.9 (160) | 10.5 (186) |

excluded participants: defined as those who attended OAI 48-month clinical visits who were not included in our analyses, n=2007

excluded participants: defined as those who attended OAI 48-month clinical visits, AND had 48-month x-ray data who were not included in our analyses, n=1778

excluded participants: those who attended OAI 48-month clinical visits, AND had 48-month x-ray data who did not have bilateral prostheses who were not included in our analyses, n=1776.

Figure 2.

Histograms of WOMAC pain score stratified by Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) grade.

Figure 3.

Histograms of Pain and Activity Knee Symptom 1 (PAKS1) scores stratified by Kellgren Lawrence (K-L) grade. All scores greater than 400 were included in the highest histogram bar.

Figure 4.

Histograms of Pain and Activity Knee Symptom 2 (PAKS2) scores stratified by Kellgren Lawrence (K-L) grade. All scores greater than 100 were included in the highest histogram bar.

The median raw WOMAC pain scores by Kellgren and Lawrence grades 0 to 4 were 0, 0, 1, 1, and 4 respectively (figure 2). The PAKS1 and PAKS2 median scores by Kellgren and Lawrence grades 0 to 4 were 23, 27, 35, 42, and 111 respectively (figure 3) and 7, 8, 10, 13, and 29 respectively (figure 4).

For the quantile regression analyses, the p for trend across all Kellgren and Lawrence grades to symptom measures based on WOMAC pain and PAKS scores were all statistically significant (p<0.001), unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. Adjusted median WOMAC by KL grades 0 – 4 were 0, 0, 1, 1, and 3 respectively. Median PAKS1 and PAKS2 were 24.9, 26.0, 32.4, 46.1, 97.9, and 7.2, 7.2, 9.2, 12.9, 23.8, respectively. (The ranges for the step and activity counts were 449 – 22,492 and 16,510 – 1,081,502 respectively and the ranges for PAKS1 and PAKS2 were 4.5 – 3,340.8 and 0.9 – 908.5 respectively.) When evaluating the individual comparisons for WOMAC pain scores (Kellgren and Lawrence grade 0 versus the other grades), only comparisons with Kellgren and Lawrence grades 3 and 4 were statistically significant when adjusting for age, sex, and BMI. Notably the comparison of WOMAC pain scores between those with Kellgren and Lawrence grades 0 versus 2, a standard cut off used for a diagnosis of OA, was not statistically significant (table 2). Meanwhile, PAKS scores showed statistically significant individual comparisons in those with Kellgren and Lawrence grades 2, 3 and 4 with grade 0 as the referent group (table 2), and additionally PAKS1 scores showed statistically significant comparisons between Kellgren and Lawrence grades 0 and 1.

Table 2.

Quantile regression: Differences in median symptom scores across radiographic severity groups. The referent group has no radiographic osteoarthritis, K-L grade 0. For all scores, higher score = greater symptoms. (n=3533 knees in 1806 participants)

| Outcome | KL 0 | KL 1 | KL 2 | KL 3 | KL 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMAC Pain | Unadjusted Median | 0 (Referent) | 0 | 1* | 2* | 4* |

| Adjusted Mediana | 0 (Referent) | 0 | 0 | 1* | 3* | |

| PAKS1 | Unadjusted Median | 22.9 (Referent) | 26.3* | 33.4* | 47.2* | 103.0* |

| Adjusted Mediana | 24.9 (Referent) | 26.0* | 32.4* | 46.1* | 97.9* | |

| PAKS2 | Unadjusted Median | 6.7 (Referent) | 7.5* | 9.8* | 14.3* | 26.1* |

| Adjusted Mediana | 7.2 (Referent) | 7.2 | 9.2* | 12.9* | 23.8* | |

Adjusted for age, sex, and BMI

Statistical difference of group median compared to the referent (KL score of 0) median; p<0.05.

PAKS1 (Pain Activity Knee Symptom1) = ((WOMAC Pain + 1) / daily step count)*100,000)

PAKS2 (Pain Activity Knee Symptom2) = ((WOMAC Pain + 1) / daily activity count)*1,000,000)

In sensitivity analyses where the WOMAC pain score was replaced with the visual analogue scale (VAS), the physical activity normalized VAS scores did allow for a greater spread across the KL grades, but these differences were not robust to adjustment for age, sex and BMI. (Data not shown.)

Discussion

Our study has shown that use of a composite score reflecting pain adjusted for level of physical activity improves symptom discrimination across radiographic OA severity grades compared to a measure of pain alone. The use of a composite score also addresses the problem of the floor effect seen in measures of pain alone. These findings inform the pressing need for a paradigm shift in evaluating knee OA symptoms. It is not sufficient to consider pain alone. Symptom assessment in knee OA needs to account for pain levels adjusted for physical activity level in both the clinical and research settings. Consider a person who runs a 26.2 mile marathon who complains of mild pain as compared to a person who walks a mile and complains of the same level of pain severity. Although both people report the same pain intensity, the latter individual is more symptomatic if we view the pain in the context of activity. The fact that people are able to modify activities to avoid pain may be an important contributor to why pain is not universal in people with radiographic OA. This may explain why Lawrence et al concluded that radiographic evidence of OA and pain were discordant and specifically why those with the greatest radiographic severity of OA did not universally complain of frequent pain6.

The focus on knee pain alone to reflect knee OA symptoms is potentially a source of misclassification of clinical knee OA severity which may have widespread consequences in both the clinical and research setting. It may contribute to the challenge researchers have faced in the effort to successfully identify risk factors for symptoms in knee OA. It is also potentially a source of inappropriate clinical management of patients with knee OA in the clinical setting. Consider the person who modified his activities so that he only has a mild level of pain. When assessed on pain intensity alone, this person would be viewed as minimally symptomatic; when assessed in the setting of pain and physical activity level, this person will be viewed as being very symptomatic. In a study by Riddle et al, expert opinion only considered pain in determining symptoms related to OA to create the algorithm assessing appropriateness of arthroplasties20. This algorithm ultimately led to the conclusion that 30% of those people having total knee arthroplasty did not have appropriate indications for those procedures20. The largest group of arthroplasties classified as inappropriate was a group of people who had mild pain, and of those, 20% had Kellgren-Lawrence grade 4 on their radiographs20. We suspect if physical activity levels were considered in addition to pain when evaluating symptoms, a substantial portion of this group of people would likely be reclassified as appropriate for arthroplasty. The natural history of OA tends to be long, so patients may not realize the activities they relinquish to modify their joint symptoms. If clinicians are not on alert to also ask patients about their level of activity, this may lead to inadvertent delay of referrals for total knee replacement.

This study also illustrates the severe floor effect of the WOMAC (figure 2). For each of the OA radiographic severity levels, except for the most severe level, approximately 50% had a WOMAC score of 0. For a scale that has a range of 20 points, the median score for the worst radiographic severity level was only 4, further emphasizing this problem. Those with WOMAC of 0, had a wide range of step and activity counts which allowed for a greater spread of PAKS scores which largely helped to address the floor effect of the WOMAC. In a community-based population survey of knee pain, where no minimum level of pain was required, the WOMAC demonstrated a similar floor effect21. This floor effect is often not seen in clinical trials of knee OA22–29, potentially because these trials pre-select those who have knee pain to enter into these studies, as recommended by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Criteria for the diagnosis of OA30. In that setting, people enrolled into these studies may represent select population with more severe symptoms, excluding those who may have modified activities to avoid daily knee pain. This scenario is also a plausible explanation for why a small clinical trial that used ACR Criteria for OA as inclusion criteria did not show clear discriminative superiority of their own exploratory composite pain and physical activity score over pain alone31. Perhaps it is time to critically re-examine and revise the ACR Criteria for OA. If the window of opportunity to intervene in knee OA exists early in disease, then there is a strong need to conduct clinical trials that include people without regard to a minimal pain requirement. Equally important, a symptom score is needed which is more sensitive to differences among people with early disease than current assessments of pain.

This study highlights the importance of tailoring symptom outcome measures to a specific disease. People who have OA usually are most symptomatic with activity. Researchers have understood this concept which is why disease specific outcomes have been developed and used including the WOMAC13. This established OA outcome measure has attempted to assess pain intensity and frequency without capturing the idea that people with OA avoid the activities that tend to precipitate their symptoms to minimize their pain. While our findings support the improved sensitivity of physical activity normalized WOMAC pain scores, benefits of normalization may not generalize to all pain measures.

Pain and physical activity should be viewed as one construct when evaluating symptoms in knee OA. The poor ability of pain intensity to predict physical activity levels reported in a recent observational study32 may be due to the modification of pain through physical activity. Our study demonstrates radiographic OA severity is associated with knee symptoms when viewed as the collective construct of knee pain adjusted for physical activity. This observation supports findings reported from qualitative research that people, in fact, do reduce their physical activity to lessen their pain experience related to knee OA7.

Modern technology makes the assessment of physical activity simple. The PAKS1 combined measure that incorporated step count performed as well or better than the PAKS2 measure that incorporated activity count. Step counts can be provided by a pedometer, a less expensive tool compared with the accelerometer used in this study. Therefore quantitation of self-selected levels of physical activity is affordable and should be routinely assessed in studies of knee OA as they provide an important dimension of symptom assessment in the disease. Comprehensive assessments of PAKS1 and PAKS2 in a longitudinal setting are needed to understand their responsiveness over time. It will also be of great interest to understand their relationship with OA features measured using other imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging where greater anatomic detail is available as compared with radiographs.

In summary, symptom assessments incorporating pain and physical activity were more discriminative than pain alone across radiographic OA severity levels, particularly among the lower severity levels. The combined measures also did not exhibit as severe a floor effect as observed with WOMAC, the standard assessment for knee OA pain. It is important to consider pain assessment in the context of physical activity level to assess knee OA symptoms in clinical studies and in clinical practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Grace Lo had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Dr. Lo is supported by K23 AR062127, an NIH/NIAMS funded mentored award, providing support for design and conduct of the study, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation and review of this work. This work is supported in part with resources at the VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13-413), at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. Accelerometer physical activity data in the Osteoarthritis Initiative was supported by NIH/NIAMS funding (R01 AR054155, R21 AR059412and P60 AR064464) providing support for design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation and review of this work. Periarticular Bone Density as a Biomarker for Early Knee Osteoarthritis was sponsored by NIH/NIAMS (McAlindon R01 AR 060718) providing support for design and conduct of the study, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation and review of this work. Dr. Hawker receives support as the Sir John and Lady Eaton Professor and Chair, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto. The Osteoarthritis Initiative is a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the Osteoarthritis Initiative Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the Osteoarthritis Initiative is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript has received the approval of the Osteoarthritis Initiative Publications Committee based on a review of its scientific content and data interpretation.

References

- 1.Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, Hirsch R. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991–94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(11):2271–2279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. Jama. 2012;307(5):491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieppe PA, Cushnaghan J, Shepstone L. The Bristol 'OA500' study: progression of osteoarthritis (OA) over 3 years and the relationship between clinical and radiographic changes at the knee joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5(2):87–97. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(97)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dieppe PA. Relationship between symptoms and structural change in osteoarthritis. what are the important targets for osteoarthritis therapy? J Rheumatol Suppl. 2004;70:50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannan MT, Felson DT, Pincus T. Analysis of the discordance between radiographic changes and knee pain in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(6):1513–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence JS, Bremner JM, Bier F. Osteo-arthrosis. Prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis. 1966;25(1):1–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawker GA, Stewart L, French MR, Cibere J, Jordan JM, March L, et al. Understanding the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis--an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(4):415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis AM, Perruccio AV, Canizares M, Hawker GA, Roos EM, Maillefert JF, et al. Comparative, validity and responsiveness of the HOOS-PS and KOOS-PS to the WOMAC physical function subscale in total joint replacement for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(7):843–847. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson SR, Archibald A, Davis AM, Badley E, Wright JG, Hawker GA. Is self-reported improvement in osteoarthritis pain and disability reflected in objective measures? J Rheumatol. 2007;34(1):159–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leffondre K, Abrahamowicz M, Regeasse A, Hawker GA, Badley EM, McCusker J, et al. Statistical measures were proposed for identifying longitudinal patterns of change in quantitative health indicators. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1049–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlop DD, Song J, Semanik PA, Chang RW, Sharma L, Bathon JM, et al. Objective physical activity measurement in the osteoarthritis initiative: Are guidelines being met? Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3372–3382. doi: 10.1002/art.30562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellamy N. WOMAC: A 20-Year Experiential Review of a Patient-Centered Self-Reported Health Status Questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(12):2473–2476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman R, Brandt KD, Hochberg MC, Moskowitz R. Design and conduct of clinical trials in patients with osteoarthritis: recomendations from a task force of the Osteoarthritis Research Society. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 1996;4:217–243. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumahara H, Schutz Y, Ayabe M, Yoshioka M, Yoshitake Y, Shindo M, et al. The use of uniaxial accelerometry for the assessment of physical-activity-related energy expenditure: a validation study against whole-body indirect calorimetry. Br J Nutr. 2004;91(2):235–243. doi: 10.1079/BJN20031033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Central Reading of Knee X-rays for K-L Grade and Individual Radiographic Features of Knee OA. http://oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelease/SASDocs/kXR_SQ_BU_descrip.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altman RD, Gold GE. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(Suppl A):A1–A56. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Project 15 Test-Retest Reliability of Semi-quantitative Readings from Knee Radiographs. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riddle DL, Jiranek WA, Hayes CW. Use of a validated algorithm to judge the appropriateness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: a multicenter longitudinal cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(8):2134–2143. doi: 10.1002/art.38685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P. Measuring the population impact of knee pain and disability with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain. 2002;100(1–2):55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reginster JY, Badurski J, Bellamy N, Bensen W, Chapurlat R, Chevalier X, et al. Efficacy and safety of strontium ranelate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: results of a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(2):179–186. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAlindon T, LaValley M, Schneider E, Nuite M, Lee JY, Price LL, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on progression of knee pain and cartilage volume loss in patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(2):155–162. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.164487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bingham CO, 3rd, Buckland-Wright JC, Garnero P, Cohen SB, Dougados M, Adami S, et al. Risedronate decreases biochemical markers of cartilage degradation but does not decrease symptoms or slow radiographic progression in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee: results of the two-year multinational knee osteoarthritis structural arthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(11):3494–3507. doi: 10.1002/art.22160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spector TD, Conaghan PG, Buckland-Wright JC, Garnero P, Cline GA, Beary JF, et al. Effect of risedronate on joint structure and symptoms of knee osteoarthritis: results of the BRISK randomized, controlled trial [ISRCTN01928173] Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(3):R625–R633. doi: 10.1186/ar1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snijders GF, van den Ende CH, van Riel PL, van den Hoogen FH, den Broeder AA. The effects of doxycycline on reducing symptoms in knee osteoarthritis: results from a triple-blinded randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(7):1191–1196. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.147967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giansiracusa JE, Donaldson MS, Koonce ML, Lefton TE, Ruoff GE, Brooks CD. Ibuprofen in osteoarthritis. South Med J. 1977;70(1):49–52. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197701000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrero-Beaumont G, Ivorra JA, Del Carmen Trabado M, Blanco FJ, Benito P, Martin-Mola E, et al. Glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study using acetaminophen as a side comparator. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(2):555–567. doi: 10.1002/art.22371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, Klein MA, O'Dell JR, Hooper MM, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(8):795–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trudeau J, Van Inwegen R, Eaton T, Bhat G, Paillard F, Ng D, et al. Assessment of Pain and Activity Using an Electronic Pain Diary and Actigraphy Device in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial of Celecoxib in Osteoarthritis of the Knee. Pain Pract. 2014 doi: 10.1111/papr.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White DK, Tudor-Locke C, Felson DT, Gross KD, Niu J, Nevitt M, et al. Do radiographic disease and pain account for why people with or at high risk of knee osteoarthritis do not meet physical activity guidelines? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):139–147. doi: 10.1002/art.37748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]