Abstract

Background

This study used Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) to address low participation of racial and ethnic minorities in medical research and the lack of trust between underrepresented communities and researchers.

Methods

Using a community and academic partnership in July 2012, residents of a South Los Angeles neighborhood were exposed to research recruitment strategies: referral by word‐of‐mouth, community agencies, direct marketing, and extant study participants.

Results

Among 258 community members exposed to recruitment strategies, 79.8% completed the study. Exposed individuals identified their most important method for learning about the study as referral by study participants (39.8%), community agencies (30.6%), word‐of‐mouth (17.5%), or direct marketing promotion (12.1%). Study completion rates varied by recruitment method: referral by community agencies (88.7%), referral by participants (80.4%), direct marketing promotion (86.2%), word of mouth (64.3%).

Conclusions

Although African American and Latino communities are often described as difficult to engage in research, we found high levels of research participation and completion when recruitment strategies emerged from the community itself. This suggests recruitment strategies based on CPPR principles represent an important opportunity for addressing health disparities and our high rates of research completion should provide optimism and a road map for next steps.

Keywords: Community Partnered Participatory Research, translational science, recruitment, trust, African American, Latino

Background

Despite bearing an unequal burden of disease, African Americans (AA) and Latinos continue to be underrepresented in medical research. This threatens both the internal and external validity of evidence designed to improve healthcare delivery and population health.1, 2 Health disparities in minority populations persist in part because strategies to improve the delivery of evidence‐based practices and services are not being tested adequately within these communities. In fact, barriers to recruitment and participation are relevant to a broad collection of research bodies, including clinical efficacy, health promotion, health services research, and the broad field of clinical and translational science research. Low levels of participation of minority populations in medical research calls attention to a history of both a lack of opportunity1 and lack of trust between affected communities and research sponsors.3, 4, 5, 6 However, despite increasing recognition of the need to engage minorities in research,7, 8, 9 limited data are available about effective engagement and strategies to address both opportunity‐ and trust‐related barriers to research participation.10, 11, 12 Furthermore, poor representation of minorities in research results in inequitable distribution of the risks and benefits of research participation and mitigates the generalizability of trial results.1

The use of a registry has been recognized as a valuable tool in developing a representative sample for medical research. However, successful recruitment of minority and underserved communities in the United States requires attention to a longstanding lack of trust and negative beliefs about healthcare systems and research. Community‐academic partnerships (CAP) have potential to respond to these longstanding challenges by creating sustainable relationships based on bi‐directional knowledge exchange, trust, and transparency. These partnerships can then serve as a foundation for involving underrepresented communities in relationships that will lay the groundwork for research engagement.13 In this way, we can build toward the much needed participation in research of a sustainable cohort that is fully representative of the population, including racial/ethnic minorities and enhance the validity of clinical research and healthcare strategies for improving the delivery of evidence‐based practices and services.

Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) is an approach that equitably involves partnership between community and academics in all phases of the research process.14 With CPPR, partners are valued equally and collaborate jointly in research development, implementation, dissemination, and framing of research questions.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Critical CPPR issues include research questions that reflect community priorities, and projects that provide real‐world solutions that enhance both community and academic research capacity.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 In this context, community‐partnered research provides implementation strategies that afford a greater opportunity to build trust.29, 30

“The State of Black Los Angeles” report by the Los Angeles Urban League (LAUL) and United Way of Greater Los Angeles revealed critical disparities between AA, Latino, Asian and Caucasian communities.31 In response to this report, a CAP involving two community organizations, the LAUL and Healthy African American Families, and one academic organization, the University of California at Los Angeles Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UCLA CTSI including UCLA, Charles R. Drew University, LA Biomed, and Cedars Sinai), launched the Healthy Community Neighborhood Initiative (HCNI), a CPPR project. HCNI is composed of representatives from each of the aforementioned organizations that collectively comprise the HCNI CAP. It aims to concurrently improve health, health care, and social services received in a predominantly AA and Latino neighborhood in South Los Angeles (LA) and its surrounding communities, through translational research and outreach programs. This paper documents the development, implementation, and outcomes of four CPPR‐based recruitment strategies recommended by the HCNI CAP.

Methods

Context and design

Key CPPR principles informed the development of the framework used to recruit community residents (Table 1). The HCNI CAP was comprised of community residents, community organization representatives, CTSI staff and faculty. HCNI involved administration of a 2‐hour survey on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, healthcare and social service use, neighborhood features, and collection of physical measurements (anthropometry, blood pressure, functional and biomarker tests). All partners contributed in ways best suited to their specific strengths. Community members contributed to the development of the study protocol, informed consent forms, data collection tools, data analysis and interpretation during weekly meetings of HCNI. Knowledge exchange between partners facilitated the mentoring of staff, community members, faculty, and students throughout the project. A recruitment team from the HCNI CAP (1) conducted a focused literature review to identify recruitment strategies relevant to the HCNI project; (2) presented results to HCNI community and academic partners; (3) developed and utilized a rating form to prioritize selected recruitment strategies; and (4) recruited community residents for the HCNI study.

Table 1.

Principles of Community Partnered Participatory Research and their application to the Healthy Community Neighborhood Initiative (HCNI) project

Recognize the community as a unit of identity

|

Build on strengths and resources within the community

|

Facilitate collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of the research

|

Promote co‐learning and capacity building among all partners

|

Integrate and achieve a balance between research and action for the mutual benefit of all partners

|

Emphasize local relevance of public health problems and ecological perspectives that recognize and attend to the multiple determinants of health and disease

|

Involve systems development through a cyclical and iterative process

|

Disseminate findings and knowledge gained to all partners and involving all partners in the dissemination process

|

Establish a long‐term commitment to the process

|

Participants received a $25 gift card after completion of the interview portion of the study and an additional $25 gift card for completion of the physical examination. Each participant also received health aids including a pedometer, pill sorter, water bottle, and cookbook with healthy recipes, as well as a Health and Wellness Community Resource Guide that included health and social service resources within the south LA community. The UCLA CTSI Institutional Review Board approved the protocol and informed consent procedures.

Literature review

A PubMed computerized database search of published medical and social research on recruitment and retention of minorities from 2000 to 2012 generated 22 articles using the following MeSH terms: clinical trials, medical research, community, minorities, AA, Latino, Hispanic, participation, recruitment, retention, and research subjects.1, 2, 10, 11, 15, 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 Included articles evaluated recruitment and/or retention strategies as a major study objective. Excluded articles were: (1) not in English, (2) did not include an underrepresented group, or (3) did not address research participation, recruitment or retention.

Identification and rating of recruitment and retention strategies

The recruitment team produced a descriptive summary of 12 recruitment strategies identified by literature review and shared it with HCNI CAP team members. The summary included an oral presentation, an executive summary, and a tabular representation of three recruitment strategy domains that categorized the 12 recruitment strategies as indirect, direct, or as representing a CAP (see Table 2). Direct methods included those in which the study team defined the specific recipient of the recruitment effort. Community‐based organizations (CBOs) and recruitment team representatives recruited community members using their existing communication protocols. They directly introduced the project to individuals referred to community agencies, presented the project at standing or special meetings, and introduced the effort at health fairs, local churches, classrooms, or other meeting places. Indirect methods included recruitment efforts that were distributed throughout the South LA community without specific awareness of who might receive the recruitment information. For example, flyers were hung in local businesses, libraries, and parks, advertisements and newsletters were distributed, and radio announcements were included in community radio shows without a priori knowledge of who would note this information.

Table 2.

Ratings of recruitment strategies by community‐academic team members

| Recruitment strategies | Mean rating score* (SD) |

|---|---|

| Direct recruitment strategies | 2.0 (0.6) |

| Referral by community agencies | 1.0 (0) |

| Present study at existing community meetings/councils | 2.0 (1.2) |

| Present the study at health/fitness classes in the community | 2.0 (1.2) |

| Recruitment outreach in churches | 2.2 (1.1) |

| Town hall meetings | 2.8 (1.1) |

| Indirect recruitment strategies | 1.9 (0.5) |

| Word‐of‐mouth | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Postflyers | 1.9 (1.1) |

| HCNI newsletter | 2.0 (1.2) |

| Advertisement in local community radio broadcast, newspapers | 2.2 (1.4) |

| Canvass streets | 2.3 (1.1) |

| Community‐academic partnerships | 1.85 (0.4) |

| Establish a community advisory board with regular meetings | 1.6 (1.2) |

| Maintain community‐academic co‐chairs | 2.1 (1.2) |

*Ratings were based upon the best judgment of 13 community and academic team members about the relevance of the recruitment strategy to each of three criteria: (1) expected effectiveness in recruiting and retaining a sample of participants; (2) feasibility of the strategy within the time and fiscal constraints of the HCNI study; and (3) cultural meaning for the community to be engaged.

Study promotion through word of mouth was encouraged by HCNI team members. At the time participants received their study compensation, they were told that the project team would welcome adult residents of the community whom they might want to refer. Participants were not formally encouraged beyond that. Neither were they trained or compensated to refer others to the study. Nevertheless, many participants did promote the study using word of mouth, serving as agents to motivate recruitment. Active study participants referred others from within social networks (e.g., friends, coworkers, or family members). Other community members learned about the study via word of mouth (e.g., a secondary or other source). All methods provided community members with a toll‐free phone number to call to learn more about research participation.

Thirteen community and academic team members from HCNI CAP reviewed the summary, endorsed consideration of the identified recruitment strategies, and rated the strategies using a five‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (most likely to be effective) to 5 (least likely to be effective) based on their relevance to the HCNI sampling frame. Team members assigned ratings based upon the relevance of each of the recruitment strategies to three criteria: (1) expected effectiveness in recruiting and retaining a sample of community participants; (2) feasibility of the strategy within the timeline and fiscal constraints of the HCNI study; and (3) cultural meaning for the community to be engaged.

Recruitment of neighborhood participants

English or Spanish speaking community‐dwelling adults ages 18 and older who lived in this South LA community anchored by Crenshaw High School were eligible to participate. HCNI CAP members were not eligible to be study participants. The 2010 census data for the targeted neighborhood included 25,030 adults of whom 73% were AA and 20% were Latino.41 Potential participants who contacted the research team by telephone completed a 15‐minute eligibility screening. Interviewers used an open ended approach to query callers about self‐identified race/ethnicity and the recruitment strategy most influential in engaging them to participate. Race/ethnicity responses were categorized as AA, Non‐Caucasian Latino, Caucasian, or other and recruitment strategy responses were categorized as referral by participants, referral by community agencies, word of mouth, and marketing promotion.

At the start of recruitment, CBOs that served predominantly AAs were partnered with the HCNI team. This facilitated early recruitment of AAs between May 2012 and July 2013. Latino participant recruitment accelerated in January 2013 with new partnerships with Latino‐serving CBOs, translation into Spanish of consent forms and study documents, and training of Spanish‐speaking field staff. Recruitment of Latino participants was completed by December 2013.

Data analysis

We created a registry of all individuals who contacted the research team to learn more about potential involvement as a research participant. We measured community members’ reports of the recruitment strategy most influential in engaging them to participate. We identified three possible outcomes for potential participants who initiated contact with the HCNI team: study completion; ineligibility; or study noncompletion (declined before consent or data collection). Participation outcome was analyzed according to the recruitment strategy the participant identified as most influential. We present descriptive statistics and used a chi‐square and paired t‐test to analyze the outcomes of the recruitment outreach effort.

Results

The study team's mean (SD) rating for the 12 recruitment strategies was similar across all three domains (Table 2). Raters were most enthusiastic about referral by community agencies (mean 1.0, SD 0.0) and by word of mouth (mean 1.0, SD 0.0), with each assigned as the lowest score, meaning raters believed these were the strategies most likely to be effective. Town hall meetings were assigned the least favorable rating (mean 2.8, SD 1.1). Scores did not differ between the seven community and six academic members of the recruitment team who assigned ratings (p > 0.05).

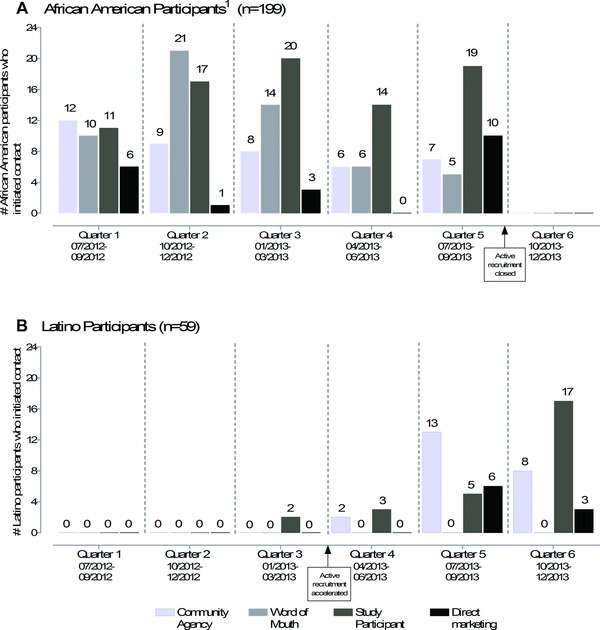

Overall, 258 potential study participants contacted the research team by telephone to learn about the study. Callers were predominantly AA (76%), Latino (23%), or other (1%) consistent with the racial/ethnic distribution documented with 2010 local census tract data at the time of study initiation.41 Over the 15‐month recruitment period, these potential participants indicated that the method that most influenced them to contact the research team about study participation was referral by study participant (39.8%), followed by referral by community agency (30.6%), word‐of‐mouth (17.5%) and direct marketing promotion (12.1%). Consistent with extant partnerships between the HCNI community and academic partners and the local AA community at the time recruitment began, materials were disseminated in English first, reaching predominantly AAs early in the study. Nine months later, after the partnership reinforced relationships with Latino CBOs, culturally sensitive, Spanish‐language materials were developed and disseminated. Figure 1 shows detailed recruitment patterns for AA and Latino participants (panels A and B respectively) for each of the four recruitment methods, stratified by time. Referral by community agencies yielded the greatest number of participants in the early phases of the recruitment effort. As time progressed, referral by study participants and word of mouth also emerged as effective recruitment methods.

Figure 1.

Quarterly recruitment of African American1 and Latino participants who initiated contact with the study team (n = 258).

1Two participants self‐identified as African American*Native American and one participant self‐identified as African American*Latino are categorized as African American. 1 Figure 1 shows detailed recruitment patterns for African American and Latino participants (panels A and B respectively) for each of the four recruitment methods, stratified by time.

Overall, across all four recruitment methods, 79.8% of the 258 potential participants who contacted the research team to learn about the study completed the study (Table 3). The remaining 9.3% declined before consent or data collection; an additional 10.9% resided outside the study boundaries and were therefore ineligible. While referral by study participants yielded the greatest number of community members who contacted the research team to learn about the research (n = 102), referral by community agencies/activities (n = 71) was associated with a higher rate of completion: 88.7% versus 80.4%. Among the 56 community members who cited word of mouth as the most important method for learning about the study, 64.3% completed the study with the others being ineligible (19.6%) or refusing (16.1%). While only 29 community members cited direct marketing promotion, this method of recruitment was effective with 86.2% completing the study; 13.8% were ineligible. In pair‐wise comparisons, participants were less likely to complete the study if referred by word‐of‐mouth compared to other recruitment methods (p ≤ 0.03 for all comparisons).

Table 3.

Self‐reported most important methods for learning about the study stratified by participant completion outcome (N = 258)

| Recruitment method: | N | Most important recruitment method among participants who completed study | Completed study | Ineligible | Declined before consent or data collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column % | Row % | ||||

| Referral by participants* | 102 | 39.8 | 80.4 | 9.8 | 9.8 |

| Referral by community agencies/activities† | 71 | 30.6 | 88.7 | 4.2 | 7.0 |

| Word‐of‐mouth‡ | 56 | 17.5 | 64.3 | 19.6 | 16.1 |

| Marketing promotion§ | 29 | 12.1 | 86.2 | 13.8 | 0.0 |

| Total | 258 | 100 | 79.8 | 10.95 | 9.3 |

*Referral by participants includes participants who learned about the study via another participant within their social network (friend, coworker, or family member).

†Referral by community agencies/activities includes participants who learned about the study directly via a community agency (i.e., The Los Angeles Urban League, Healthy African American Families, local Latino churches), community meetings/councils, classes, churches, or town hall meetings.

‡Word‐of‐mouth includes participants who learned about the study via a secondary or other source that is not a participant.

§Marketing promotion includes indirect recruitment methods which are delivered without specific awareness of who might receive the recruitment information (e.g., use of flyers and listening to local community radio broadcast, e.g., Good News Radio Magazine [43]) as distinct from methods specifically targeting individuals.

Discussion

The generalizability of research findings is a fundamental piece of the health research process. Research representative of diverse aspects of the population enhances discovery and engages healthcare systems to incorporate evidenced‐based research findings into daily practices.9 Through the adoption of CPPR principles, the HCNI community‐academic partnership developed and implemented recruitment strategies that addressed a long‐standing lack of trust, was acceptable to the community, was successful in recruiting AA and Latino participants, and is an important step in the development of a representative community cohort. Overall, 79.8% of the 258 potential participants who contacted the research team to learn about the study completed the survey, clinical evaluation, laboratory and functional tests.

The number of AA and Latino individuals enrolled in our study is an achievement notable because it signals high levels of interest and trust in research participation. This enthusiasm reflects the fact that the selected recruitment strategies emerged from the community itself. By rating recruitment strategies by their effectiveness, feasibility, and cultural appropriateness, HCNI facilitated the community's trust in the project. Embedding recruitment methods developed by community residents in a CPPR contextual framework allowed us to translate the goals and methods of research recruitment into a rigorous research protocol endowed with language and context that were familiar and understandable to potential research participants. This sent a message that was valued by community members.

Our findings contribute to a growing literature providing an effective model for recruiting an important segment of the population into research.42, 43, 44, 45 Currently, 56% of LA residents are AA or Latino.46 By 2050, 63% of LA residents and 42% of all Americans will be AA or Latino.47 Identifying recruitment strategies that are effective in recruiting AA and Latino participants will promote diversity and external validity in research and findings, addressing an important reason that clinicians, and patients, do not consistently adhere to evidence‐based practices.48

Building trust, an essential ingredient

Developing research infrastructure in the context of a CAP, builds trust by encouraging the development of transparent and collaborative methods for obtaining, analyzing, and sharing empirical findings. Our HCNI CAP research infrastructure was built upon respectful and committed engagement, infrastructure development, and compensation for efforts provided by both community and academic team members. All partners provided resources (material and human) to the development and implementation of the recruitment strategies. Community partners relied on their social network and the expertise of their staff while academic partners brought their scientific expertise and research experience to bear on the project. Incorporating scientific expertise through the HCNI CAP provided infrastructure and guidance for channeling community efforts into a viable research question and reproducible research design. Diversity at the decision table was a driving force that enabled the team with its professional, racial, and ethnic diversity, to design and implement an effective partnered research project nestled within a community setting.

A recent review of studies on factors influencing participation in health research of underserved populations found that the most frequently reported barriers to participation included mistrust of research (32%) and mistrust of the medical community (12.8%).3, 5 Alternatively, culturally competent research design (8.9%) and trusting researchers (7.6%) were among the most frequently cited motives for participation.5 The CPPR framework used in this study aimed to develop and nurture trust by engaging the residents and organizations within the community at all levels of research design and implementation. Trust was established by ethnically, culturally, and linguistically matching recruiters with participants,21, 30, 37, 39, 49, 50, 51 incorporating academic and community partners’ input into recruitment methods and materials, and partnering with key community leaders and organizations.5, 20, 52, 53, 54 Our approach avoided perpetuating the history of cultural conflict and miscommunication within undeserved communities that has resulted in many kinds of mistrust pertinent to research.1, 4, 54

Research registries have been suggested as an essential aid for recruitment in community settings.13, 55, 56, 57 However, in communities with longstanding mistrust of research, multiple methods of building awareness and opportunity may be required before the registry can be expected to be representative of all potentially eligible community members. Beginning with CAP provides a mechanism to develop recruitment methods that are consistent with community context and values, while attracting research participants who can then engage others. The participant pool we identified has already served as an important nidus that can grow to engage a broader and more representative cohort. As time progresses and CAPs mature, increasing numbers of sustainable and representative registries will likely emerge.

Strengths and limitations

In this study, we built a registry from community members who contacted the research team to learn about the study. We then calculated response rates using a rigorous denominator defined as all those who contacted the research team to learn about potential research participation. The completion of a 2‐hour in‐home survey and collection of extensive biometric data by 258 AA and Latinos represents an important accomplishment for the recruitment of minority research participants.

Despite these accomplishments, this study is limited by lack of a controlled method for determining the degree to which CPPR methods and a sustained CAP contributed successful participant recruitment. In particular, we are not able to report the precise number of individuals exposed to each of the four recruitment methods. We cannot know the number of individuals who were exposed to CBO outreach or direct marketing. Thus, it is impossible to assess if the results of the recruitment strategies could have been achieved as well or better using other methods. Nevertheless, with time and expanding opportunities for community members to participate and partner in research, these methods have potential for establishing a pool of informed research participants who can then engage others.13, 56, 57, 58, 59

Research recruitment lessons learned

The number of AA and Latino individuals enrolled in our study is a milestone worth considering because these communities are often described as difficult to engage in research. We found high levels of research interest and completion when presenting research recruitment methods that emerged from the community itself. Wendler et al.60 found very small differences in the willingness of AAs and Latinos to participate in health research compared to non‐Hispanic whites when given the opportunity to participate. Our results demonstrate that (1) recruitment is feasible, (2) different strategies appeal to different community members, and (3) community agencies play a critical role. Our time trend data show that community agencies provide the most effective recruitment approach early in a study. This is consistent with Yancey's meta‐analysis of underrepresented minority groups which revealed that community involvement either by project staff or CBOs was important for recruiting minorities to research because community involvement fostered trust.61

Our finding that study participants became effective agents for motivating others to enroll in research is consistent with evidence showing that social networking is an effective recruitment strategy among low‐income and multiethnic individuals.6, 62, 63 Social networking accounted for more than half of the participants who completed this study. The success of social networks in recruiting AA and Latino individuals can be explained by people participating based upon who they know and the receipt of positive messages from others who have completed a study.6, 64 Among those who completed the study, referral by participants and word of mouth were identified as the most important methods for motivating them to participate in the research. While we were not able to query participants about trust, in the context of the community participatory protocol for the HCNI CAP project, we interpreted community members’ participation as expressions or proxies of trust.65

Health disparities that exist along racial/ethnic and socio‐economic lines reflect barriers to, and limited involvement in, health research designed to improve patient and population outcomes.39, 66 Recruitment strategies based on CPPR principles represent an important opportunity for addressing health disparities. Our approach to the development of recruitment strategies, coupled with our findings on research study completion is novel in presenting empirical data stratified by recruitment methods overall and separately for two racial/ethnic groups. This work contributes to the understanding of engagement of under‐represented populations in health research. Enhancing the external validity of research strengthens scientific validity, generalizability, applicability and acceptability of research and interventions to much broader segments of the US population.2, 62, 63, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69

Conclusions

A unique feature of this CPPR study is the iterative bidirectional exchange between community and academia that informed the design and implementation of this study. The study anchored the recruitment approaches in the context of the community through the review and revision of protocols with input from community residents. Building upon this foundation, challenges arising during recruitment benefited from feedback from experienced CBOs, academic insights about the scientific method and transparency, and social networking between community residents. This networking involves both healthcare delivery and community organizations, as well as the people who staff them and who are served by them. Future research should focus on understanding how organizational and personal recruitment strategies can complement each other to enhance the validity of evidence based studies, while pursuing studies of the comparative effectiveness of varying strategies to engage and sustain the participation of underrepresented individuals in health research.

Conflict of Interest

The manuscript authors declare that they have no competing interests, financial or other to declare.

Authors Contributions

Katherine L. Kahn, M.D., the corresponding author, had full access to all of the data in the study. Dr. Kahn takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Ibrahima C. Sankaré, M.H.A., and Rachelle Bross, Ph.D., R.D., contributed equally to this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. •

ICS participated in the analyses, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

RB participated in the analyses, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

AFB participated in the design of the study and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

HEP participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

LFJ participated in the design of the study and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

DMM participated in the design of the study and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

CP participated in the acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

ALW participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

RV participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

NF participated in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

KCN participated in the design of the study and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

KLK participated in the analyses, interpretation of data, supervision and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Dr. Kahn certifies that all persons who have made substantial contributions to the work reported in this manuscript (e.g., data collection, analysis, writing, or editing assistance) but who do not fulfill the authorship criteria are named along with their specific contribution in an Acknowledgment in the manuscript. Dr. Kahn certifies that all persons named in the Acknowledgment section have provided written permission to be named. The following collaborators were involved in the design of the community academic partnership methods that were central to this project.

Juan Barron, BA, UCLA CTSI Data collection, recruitment outreach to the Latino community

Dennishia Banner, Healthy African American Families Collection of Physical measurements (e.g., anthropometry, blood pressure, functional and biomarker tests)

Blanca Corea, MA, UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Initiative Design of recruitment strategies for the Latino community, recruitment outreach to Latino community, and data collection

Nancy Hernandez, Healthy African American Families Data collection, recruitment outreach to the Latino community

Felica Jones, Healthy African American Families Review of survey administration protocols, design of recruitment strategies for the African American community, recruitment outreach to the African American community, and data collection

Keyonna King, DrPH, UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Initiative Design and review of survey administration protocols, Design and review of physical measurement data, collection protocols, data collection

Arturo Martinez, BA, UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Initiative Data collection and recruitment outreach to the Latino community

Laurice Pitts, LVN, Charles Drew University Design and review of physical measurement data collection protocols

Stefanie D. Vassar, MS, UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Initiative Review and interpretation of data analysis (e.g., p‐values, self‐reported most important methods for learning data table)

Lujia Zhang, BS, UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Initiative Design and review of survey administration protocols and data collection.

An earlier version of this work was presented at the following meetings:

2013 Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, Denver, Colorado, April 25, 2013;

2012 Annual Research Meeting for Academy Health, Baltimore, Maryland, June 23, 2013; and

2014 Annual Research Meeting for Academy Health, San Diego, California, June 10, 2014.

Acknowledgments

The research described was supported by NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR000124 and by the USC/UCLA Center of Biodemography # 5P30AG017265‐13. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funder was not involved with the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Ford ME, Siminoff LA, Pickelsimer E, Mainous AG, Smith DW, Diaz VA, Soderstrom LH, Jefferson MS, Tilley BC. Unequal burden of disease, unequal participation in clinical trials: solutions from African American and Latino community members. Health Soc Work. 2013. Feb; 38(1): 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998; 19(1): 173–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race‐, sex‐, and age‐based disparities. JAMA. 2004; 291: 2720–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corbie‐Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody‐Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999; 14:537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spears CR, Nolan BV, O'Neill JL, Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Feldman SR. Recruiting underserved populations to dermatologic research: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2011; 50: 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mendez‐Luck CA, Trejo L, Miranda J, Jimenez E, Quiter ES, Mangione CM. Recruitment strategies and costs associated with community‐based research in a Mexican‐origin population. Gerontologist. 2011. Jun; 51(Suppl 1): S94–S105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. House JS, Williams DR. Understanding and reducing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in health In: Smedley BD, Syme LS, eds. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2000: 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kahn KL, Ryan G, Beckett M, Taylor S, Berrebi C, Cho M, Quiter E, Fremont A, Pincus H. Bridging the gap between basic science and clinical practice: a role for community clinicians. Implement Sci. 2011; 6: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pinto RM, McKay MM, Escobar C. “You‘ve gotta know the community”: minority women make recommendations about community‐focused health research. Women's Health. 2008; 47(1): 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martinez CR, McClure HH, Eddy JM, Ruth B, Hyers MJ. Recruitment and retention of Latino immigrant families in prevention research. Prev Sci. 2012; 13: 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahmed SM, Palermo AS. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. 2010. August; 100(8): 1380–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chadiha, LA , Washington OG, Lichtenberg PA, Green CR, Daniels KL, Jackson JS. Building a registry of research volunteers among older urban African Americans: recruitment processes and outcomes from a community‐based partnership. Gerontologist. 51(Suppl 1): S106–S115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007; 297(4): 407–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, Rhodes S, SamuelHodge C, Maty S, Lux, L , et al. Community‐based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 99. 2004; (Prepared by RTI–University of North Carolina). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Prevention Institute , A Community Approach to Address Health Disparities: Thrive Toolkit for Health & Resilience in Vulnerable Environments, Office of Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. September 2004; http://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/assets/pdf/checked/THRIVE_FinalProjectReport_093004.pdf (Last Accessed September 19, 2013).

- 17. Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community‐based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006; 7: 312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horowitz CR, Brenner BL Lachapelle S, Amara, DA , Arniella, G . Effective recruitment of minority populations through community‐led strategies. Am J Prevent Med. 2009; 37(6): S195–S200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dulin M, Tapp H. Communities matter: the relationship between neighborhoods and health. N C Med J. 2012; 73(5): 381–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Las Nueces, D , Hacker K, DiGirolamo A, Hicks LS. A systematic review of community‐based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Services Res. 2012; 47(3, part II): 1363–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith SA, Blumenthal DS. Community health workers support community‐based participatory research ethics: lessons learned along the research‐to‐practice‐to‐community continuum. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012; 23(4): 77–87. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved August 8, 2013, from Project MUSE database. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Escobar‐Chaves SL, Tortolero SR, Masse LC, Watson KB, Fulton JE. Recruiting and retaining minority women: findings from the women on the move study. Ethn Dis. 2002; 12: 242–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Institute of Mental Health, Points to Consider about Recruitment and Retention While Preparing a Clinical Research Study . 2005. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/funding/grant‐ writing‐and‐application‐process/recruitment‐points‐to‐consider‐6‐1‐05.pdf. (Accessed February 6, 2014).

- 24. UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: a systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007; 22(6): 852–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson VA, Powell‐Young YM, Torres ER, Spruill IJ. A systematic review of strategies that increase the recruitment and retention of African American adults in genetic and genomic studies. ABNF J. 2011. Winter; 22(4): 84–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dilworth‐Anderson P. Introduction to the science of recruitment and retention among ethnically diverse populations. Gerontologist. 2011. Jun; 51(Suppl 1): S1–S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barnett J, Aguilar S, Brittner M, Bonuck K. Recruiting and retaining low‐income, multi‐ethnic women into randomized controlled trials: successful strategies and staffing. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012; 33: 925–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De La Rosa M, Babino R, Rosario A, Martinez NV, Aijaz L. Challenges and strategies in recruiting, interviewing, and retaining recent Latino immigrants in substance abuse and HIV epidemiologic studies. Am J Addict. 2012. Jan‐Feb; 21(1): 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. NIH Director's Council of Public Representatives . Report and Recommendations on Public Trust in Clinical Research from NIH Director's Council of Public Representatives. 2005; http://copr.nih.gov/reports/public_trust.asp. (Accessed February 4, 2014).

- 30. Corbie‐Smith G, Thomas SB, St. George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002; 162: 2458–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. The State of Black Los Angeles . The Los Angeles Urban League and United Way of Greater Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA: 2005; http://www.calendow.org/uploadedfiles/state_of_black_la.pdf (Accessed March 1, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burns D, Soward A, Skelly AH, Leeman J, Carleson J. Effective recruitment and retention strategies for older members of rural minorities. Diabetes Educ. 2008; 34: 1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Falcon R, Bridge DA, Currier J, Squires K, Hagins D, Schaible D, Ryan R, Mrus J. Recruitment and retention of diverse populations in antiretroviral clinical trials: practical applications from the gender, race and clinical experience study. Int J Womens Health. 2011; 20(7): 1043–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ejiogu N, Norbeck JH, Mason MA, Cromwell BC, Zonderman AB, Evens MK. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: lessons from the healthy aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the life span study. Gerontologist. 2011; 51(S1): S33–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wiemann CM, Chacko MR, Tucker JC, Velasquez MM, Smith PB, DiClemente RJ, Von Stemberg K. Enhancing recruitment and retention of minority young women in community‐based clinical research. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005; 18: 403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burke JG, Hess S, Hoffmann K, Guizzetti L, Loy E, Gielen A, Bailey M, Walnoha A, Barbee G, Yonas M. Translating community‐based participatory research principles into practice. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2013. Summer; 7(2): 115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pinto HA, McCaskill‐Stevens W, Wolfe P, Marcus AC. Physician perspectives on increasing minorities in cancer clinical trials: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Initiative. Ann Epidemiol. Nov 2000; 10(8 Suppl): S78–S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Makhoul J, Nakkash R, Harpham T, Qutteina Y. Community‐based participatory research in complex settings: clean mind–dirty hands. Health Promot Int. 2014; 29(3): 510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fortune T, Wright E, Juzang I, Bull S. Recruitment, enrollment and retention of young black men for HIV prevention research: experiences from The 411 for Safe Text Project. Contemp Clin Trials. Mar 2010; 31(2): 151–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Satcher D. Eliminating racial and ethnic disparities in health: the role of the ten leading health indicators. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000; 92(6): 315–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. United States Census Bureau American Fact Finder. http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF1_QTP3&prodType=table. (Accessed February 5, 2014).

- 42. Miranda J, Nakamura R, Bernal G. Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: a practical approach to a long‐standing problem. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003; 27(4): 467–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Calderón JL, Baker RS, Fabrega H, Hays RD, Fleming E, Norris K. An ethno‐medical perspective on research participation: a qualitative pilot study. MedGenMed. 2006; 8(2): 23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Vida P, Warda US. Strategies to recruit and retain older Filipino‐American immigrants for a cancer screening study. J Community Health. 2005; 30(3): 167–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wyatt SB, Diekelmann N, Henderson F, Andrew ME Billingsley G, Felder SH, Fuqua S, Jackson PB. A community driven model of research participation: the Jackson Heart Study participant recruitment and retention study. Ethn Dis. 2003; 13(4): 438–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. United States Census Bureau American Fact Finder. http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF2_SF2DP1&prodType=table

- 47. California Department of Finance. http://www.dof.ca.gov/research/demographic/reports/projections/p‐1/. (Accessed February 19, 2014)

- 48. McNeil BJ. Shattuck Lecture – hidden barriers to improvement in the quality of care. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345: 1612–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Duhl L. In: Kurland J, ed. Public Health Reports. V115(2–3). Cary, NC: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Smith YR, Johnson AM, Newman LA, Greene A, Johnson TR, Rogers JL. Perceptions of clinical research participation among African American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007; 16: 423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sharp RR, Foster MW. Involving study populations in the review of genetic research. J Law Med Ethics 2000; 28(1): 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jones RA, Steeves R, Williams I. Strategies for recruiting African American men into prostate cancer screening studies. Nurs Res. 2009. Nov–Dec; 58(6): 452–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carroll JK, Yancey KY, Spring B, Figueroa‐Moseley C, Mohr DC, Mustian KM, Fiscella K. What are successful recruitment and retention strategies for underserved populations? Examining physical activity interventions in primary care and community settings. Transl Behav Med. 2011; 1: 234–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Giuliano AR, Mokuau N, Hughes C, Tortolero‐Luna G, Risendal B, Ho RCS, Prewitt TE, McCaskill‐Stevens WJ. Participation of minorities in cancer research: the influence of structural, cultural, and linguistic factors. Ann Epidemiol. 2000; 10(8suppl): S22–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Green MA, Kim MM, Barber S, Odulana AA, Godley PA, Howard DL, Corbie‐Smith G. Connecting communities to health research: development of the Project CONNECT minority research registry. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013; 35: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lichtenberg PA. The generalizability of a participant registry for minority health research. Gerontologist. 51(Supp 1): S116–S124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, Gary TL, Bolen S, Gibbons MC, Tilburt J, Baffi C, Tanpitukpongse TP, Wilson RF, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2007; 112: 228–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paskett ED, Reeves KW, McLaughlin JM, Katz ML, McAlearney AS, Ruffin MT, Halbert CH, Merete C, Davis F, Gehlert S. Recruitment of minority and underserved populations in the United States: the Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities experience. Contemp Clin Trials. 29(6): 847–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014. Feb; 104(2): e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, Van Wye G, Christ‐Schmidt H, Pratt LA, Brawley OW, Gross CP, Emanuel E. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006; 3(2): e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006; 27: 1–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Appel LJ, Vollmer WM, Obarzanek E, Aicher KM, Conlin PR, Kennedy BM, Charleston JB, Reams PM. Recruitment and baseline characteristics of participants in the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999; 99(Suppl): S69–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kennedy BM, Kumanyika S, Ard JD, Reams P, Johnson CA, Karanja N, Charleston JB, Appel LJ, Maurice V, Harsha DW. Overall and minority‐focused recruitment strategies in the PREMIER multicenter trial of lifestyle interventions for blood pressure control. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010; 31: 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grim P, Thomas SB, Fisher S, Reade C, Singer DJ, Garza MA, Fryer CS, Chatman J. Polarization and belief dynamics in the black and white communities: an agent‐based network model. from the data. Artif Life. 2012, 13: 186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Van Hoorn A. Individualist–collectivist culture and trust radius: a multilevel approach. J Cross‐Cultural Psychol. 2015; 46(2): 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Minority Health and Health Disparities Research and Education Act. United States Public Law. 2000; 106–5 25; 2498. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sung NS, Crowley WF, Genel M, Salber P, Sandy L, Sherwood LM, Johnson SB, Catanese V, Tilson H, Getz K, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA., March 12, 2003; 289(10): 1278–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kagawa‐Singer M. Improving the validity and generalizability of studies with underserved US populations: expanding the research paradigm. Ann Epidemiol. 2000; 10(8, suppl): S92–S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Institute of Medicine . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]