Abstract

Background

Infectious complications of musculoskeletal trauma are an important factor contributing to patient morbidity. Biofilm-dispersive bone grafts augmented with d-amino acids (d-AAs) prevent biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo, but the effects of d-AAs on osteocompatibility and new bone formation have not been investigated.

Questions/purposes

We asked: (1) Do d-AAs hinder osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation in vitro? (2) Does local delivery of d-AAs from low-viscosity bone grafts inhibit new bone formation in a large-animal model?

Methods

Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S aureus clinical isolates, mouse bone marrow stromal cells, and osteoclast precursor cells were treated with an equal mass (1:1:1) mixture of d-Pro:d-Met:d-Phe. The effects of the d-AA dose on biofilm inhibition (n = 4), biofilm dispersion (n = 4), and bone marrow stromal cell proliferation (n = 3) were quantitatively measured by crystal violet staining. Osteoblast differentiation was quantitatively assessed by alkaline phosphatase staining, von Kossa staining, and quantitative reverse transcription for the osteogenic factors a1Col1 and Ocn (n = 3). Osteoclast differentiation was quantitatively measured by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining (n = 3). Bone grafts augmented with 0 or 200 mmol/L d-AAs were injected in ovine femoral condyle defects in four sheep. New bone formation was evaluated by μCT and histology 4 months later. An a priori power analysis indicated that a sample size of four would detect a 7.5% difference of bone volume/total volume between groups assuming a mean and SD of 30% and 5%, respectively, with a power of 80% and an alpha level of 0.05 using a two-tailed t-test between the means of two independent samples.

Results

Bone marrow stromal cell proliferation, osteoblast differentiation, and osteoclast differentiation were inhibited at d-AAs concentrations of 27 mmol/L or greater in a dose-responsive manner in vitro (p < 0.05). In methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S aureus clinical isolates, d-AAs inhibited biofilm formation at concentrations of 13.5 mmol/L or greater in vitro (p < 0.05). Local delivery of d-AAs from low-viscosity grafts did not inhibit new bone formation in a large-animal model pilot study (0 mmol/L d-AAs: bone volume/total volume = 26.9% ± 4.1%; 200 mmol/L d-AAs: bone volume/total volume = 28.3% ± 15.4%; mean difference with 95% CI = −1.4; p = 0.13).

Conclusions

d-AAs inhibit biofilm formation, bone marrow stromal cell proliferation, osteoblast differentiation, and osteoclast differentiation in vitro in a dose-responsive manner. Local delivery of d-AAs from bone grafts did not inhibit new bone formation in vivo at clinically relevant doses.

Clinical Relevance

Local delivery of d-AAs is an effective antibiofilm strategy that does not appear to inhibit bone repair. Longitudinal studies investigating bacterial burden, bone formation, and bone remodeling in contaminated defects as a function of d-AA dose are required to further support the use of d-AAs in the clinical management of infected open fractures.

Introduction

Infectious complications are an important factor contributing to patient morbidity and limiting the success of clinical management of complex trauma [9, 32, 36]. Treatment of bone infections in patients with fractures can involve operative débridement of necrotic bone followed by several weeks of systemic antibiotics, temporary fixation, and/or implantation of devices to promote bone regeneration [11, 44]. For orthopaedic infections, Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly isolated agent, accounting for more than ½ of all infections [28]. In addition to increasing trends of antimicrobial resistance, the ability of bacteria to develop and persist in biofilms on implanted biomedical devices is recognized as a major factor contributing to chronic relapsing infections and nonosseous union [4, 35, 42, 44, 48, 49].

Bacterial biofilms are a protected mode of growth characterized by a high tolerance to the activity of antimicrobials compared with planktonic bacteria, which is partly attributable to the limited permeability of antimicrobials through the extracellular matrix surrounding the bacteria and the reduced metabolic state of the persister cells in the biofilm [11, 28, 44, 50]. Although clinical studies have underscored the relationship between infection and nonunion of diaphyseal fractures [24], periarticular fractures also have high rates of infections complications. The deep infection rate of patients with Schatzker Type VI bicondylar tibial plateau fractures treated by a two-incision dual-plating technique ranged from 11% to 23% [1, 43] and approached 30% if treated more than 72 hours after injury [19]. Thus, inhibiting the formation of a biofilm may be an alternative strategy for reducing the incidence of infectious complications and nonunions. Several reviews have highlighted the need for biomaterials that deter establishment of an infection by concurrently inhibiting biofilm formation and promoting tissue integration and regeneration [44, 45, 53]. The d-isomers of amino acids (d-AAs) prevent and disperse biofilms formed by a broad range of bacterial species, including S aureus [23, 26], by inhibiting initial bacterial attachment to surfaces [55], inhibiting localization of cell-cell adhesion proteins at the cell surface [23, 26], inhibiting expression of biofilm matrix genes [27], and promoting release of amyloid fibers from the cell wall [26]. Furthermore, d-AAs have minimal toxicity toward eukaryotic cells [16, 41]. However, the doses at which d-AAs are effective against S aureus are the subject of debate, with some studies reporting biofilm inhibition at concentrations of 100 to 500 μm [8, 23, 38, 56], whereas another showed that higher concentrations (up to 10 mmol/L) are required for biofilm dispersal in vitro [41]. Similarly, the effects of d-AA dose on mammalian cells have not been extensively investigated. Scaffolds augmented with greater than 50 mmol/L d-AAs have been shown to reduce the incidence of infection and microbial burden when implanted in rat segmental defects contaminated with clinical isolates of S aureus [41]. However, to our knowledge, the effects of d-AAs on new bone formation have not been evaluated in a large-animal model.

We therefore asked: (1) Do d-AAs hinder biofilm formation, differentiation of osteoblasts (as determined by alkaline phosphatase-positive colony-forming unit [CFU-ALP] and osteoblast colony-forming unit [CFU-OB] assays), and osteoclasts (as determined by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase staining [TRAP]) in vitro in a dose-responsive manner? (2) Does local delivery of d-AAs from low-viscosity bone grafts inhibit new bone formation (as determined by μCT and histologic analysis) in a large-animal model in vivo?

Materials and Methods

In this study, we evaluated the effects of d-AA concentration on inhibition of biofilm formation and osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation in vitro. This approach enabled direct comparison of d-AA concentrations that promote antibiofilm activity while maintaining osteocompatibility. In a large-animal pilot study, d-AAs were delivered locally through a settable low-viscosity bone graft composite composed of MASTERGRAFT® ceramic Mini Granules (85% hydroxyapatite/15% beta-tricalcium phosphate; Medtronic, Memphis, TN, USA), a lysine triisocyanate-poly(ethylene glycol) prepolymer, a polyester triol, and a tertiary amine catalyst. MASTERGRAFT® is an osteoconductive ceramic reported to promote new bone formation in orthopaedic, dental, and spine applications [47, 52]. Low-viscosity grafts were augmented with 0 or 200 mmol/L d-AAs (a dose shown to promote antibiofilm activity in contaminated defects in rats [41]) and injected in ovine femoral condyle defects. New bone formation was measured by μCT and histologic analysis to assess the effects of d-AAs on new bone formation.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Clinical isolates of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA/MSSA) associated with osteomyelitis were selected from a repository collected from patients admitted for treatment at the San Antonio Military Medical Center (Fort Sam Houston, TX, USA) and not related to research (Table 1). Bacterial strains were cultured in Cation Adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth with agitation or on blood agar plates at 37°C.

Table 1.

Characteristics of bacterial strains used in this study

| Bacterial species | Pulse-field type | Phenotype | Isolate source | Site of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | ||||

| SAMMC-38 | USA700 | MRSA | Wound deep | Bone |

| SAMMC-39 | USA100 | MRSA | Wound deep | Bone |

| SAMMC-40 | Unknown | MRSA | Wound deep | Bone |

| SAMMC-41 | USA800 | MRSA | Wound deep | Bone |

| SAMMC-61 | USA300 | MSSA | Wound culture | Bone |

| SAMMC-63 | USA700 | MSSA | Wound culture | Bone |

| SAMMC-65 | USA200 | MSSA | Wound culture | Tissue |

SAMMC = San Antonio Military Medical Center; MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA = methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Biofilm Inhibition and Dispersal Assays

Biofilm formation was assessed under static conditions using the microtiter plate assay as described previously [41]. Bacterial cultures were grown in Cation Adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth to an optical density (OD)600 of 0.1 (approximately 108 CFU/mL) and diluted 1:100 in Cation Adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth. Five hundred microliters of diluted bacteria then was added and incubated at 37° C for 24 hours. To assess the biofilm dispersal activity of d-AAs, culture medium from biofilms was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing the d-AA mixture. After treatment with d-AAs for 24 hours, plates were washed with phosphate buffered saline to remove unattached cells, stained with 0.1% (weight/volume) crystal violet (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MI, USA) for 10 minutes, rinsed with phosphate buffered saline, and then solubilized with 80% (volume/volume) ethanol. Biofilm biomass was determined by measuring the absorbance of solubilized stain at 570 nm using a microtiter plate reader (n = 4). For assays measuring the ability of d-AAs to inhibit biofilm formation, bacteria were grown under the biofilm conditions as above in the presence of media containing d-AAs.

In Vitro Cell Culture

To assess the effects of d-AAs on osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation in vitro, bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) and osteoclast precursor cells were treated with 0 to 81 mmol/L total d-AAs in a 1:1:1 mixture by weight of d-methionine (Met):d-phenylalanine (Phe):d-proline (Pro). A 270 mmol/L stock solution was prepared by dissolving 1.259 g of d-Pro, 1.259 g of d-Met, and 1.259 g of d-Phe in 100 mL culture medium (αMEM; Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) at 37o C and adjusting to pH 7.5 to 8 using 0.5 N HCl. d-AA stock solution was diluted with culture medium to achieve the targeted concentration, and culture medium and d-AAs were refreshed every other day. BMSCs were isolated from long bones of adult C57 WT mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) [30]. For osteoblast differentiation, BMSCs isolated from three mice were pooled and plated at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/mL. Fifty micrograms per milliliter ascorbic acid and 5mmol/L glycerophosphate were added to culture medium 7 and 14 days after plating. ALP staining was performed 14 days after plating and the numbers of CFU-ALP were counted (n = 3). Von Kossa staining was performed 21 days after plating and the numbers of CFU-OB were counted based on their round (> 1 mm diameter) and black appearance (n = 3). For BMSC proliferation, cells isolated from three mice were pooled and plated at a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL (n = 3). After BMSCs reached 80% confluence, cells were trypsinized and replated separately in 24-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL. d-AA treatment was started 1 day after plating. Crystal violet staining was performed at different times and the OD of the released dye (OD570 nm) was used to quantify relative cell number [15, 18].

Osteoclast precursor cells were prepared from spleens of four adult C57 WT mice by the Ficoll (Lymphocyte Separation Medium; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) gradient method [6] and plated separately at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells/mL. Osteoclast differentiation was induced with 30 ng/mL of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Sigma) and 50 ng/mL of receptor activator of nuclear factor B ligand (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Osteoclast differentiation induction and the d-AA treatment started the day cells were plated. Culture medium and d-AA treatment were refreshed every other day. At Day 6, TRAP staining was performed (n = 3). The percentage of TRAP-positive area (%) was calculated by following automatic thresholding with MetaMorph® Imaging software (Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). For all in vitro tests, statistical significance was assessed by a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05), post hoc.

In Vivo Large Animal Sheep Model

Low-viscosity grafts (not approved by the FDA) implanted in vivo were prepared with the following reactive polymer: lysine triisocyanate-poly(ethylene glycol) prepolymer (21.7% NCO), a poly(ε-caprolactone [70%]-co-glycolide [20%]-co-D,L-lactide [10%]) triol (450 Da), and a triethylenediamine catalyst (10% solution in dipropylene glycol) [13, 14, 37]. An advantage of low-viscosity grafts compared with calcium phosphate cements or allograft is its ability to support diffusion-controlled sustained release of biologics [20, 41]. To test the effects of d-AAs in vivo, a 1:1:1 mixture (by weight) of d-Met:d-Phe:d-Pro was mixed by hand with the reactive polymer before injection. Low-viscosity grafts were prepared by mixing lysine triisocyanate-poly(ethylene glycol) prepolymer (index 115 [21]), polyester triol, the mixture of powdered d-AAs (0 or 200 mmol/L based on the volume of the defect), triethylenediamine, and ceramic particles (45 weight % for low viscosity and 40 weight % for low viscosity + d-AAs).

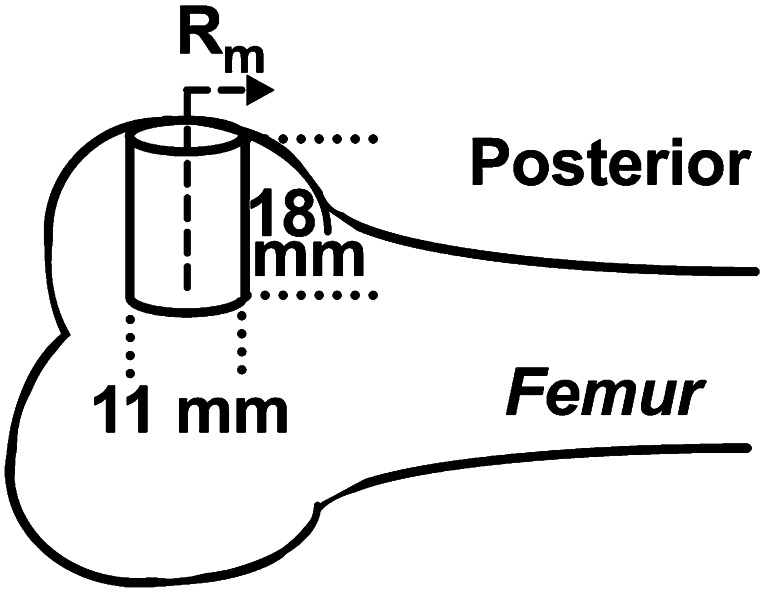

Four healthy domestic crossbred, adult, skeletally mature, female, nonpregnant sheep (Ovis aries, 54–88 kg) were used to evaluate the effects of d-AAs on bone formation. All surgical and care procedures were performed at IBEX Preclinical Research Inc (Logan, UT, USA) under aseptic conditions per Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. Preoperative butorphanol and atropine were administered. Morphine was administered as an epidural injection before surgery to provide preemptive analgesia. A semicircular incision was created in the periosteum and the periosteal flap was removed. Bilateral defects 11 × 18 mm (1.7 cm3) were drilled (Fig. 1) through a K-wire guide and reamer in the distal aspect of the lateral femoral condyle of each sheep. Before graft application, gauze was used to reduce defect hemorrhaging. Two grafts were investigated (n = 4 for each): (1) low viscosity (control) and (2) low viscosity + d-AAs (200 mmol/L, based on defect volume). Each sheep was implanted with one of each graft with two grafts implanted in the right and two in the left of four used condyles for each graft. Low-viscosity components were gamma-irradiated (25–40 kGy) by Sterigenics International Inc (Westerville, OH, USA), mixed, and injected in the defects. Wounds were closed after cure (15 minutes after implantation) as described previously [14, 37]. The primary outcome was bone volume/total volume measured by μCT in the middle region of the defect. An a priori power analysis indicated that a sample size of four would detect a 7.5% difference in bone volume/total volume between groups assuming a mean and SD of 30% and 5%, respectively in the middle region of interest of the graft (2.5 mm from the center-line) [13, 37]. This is with a power of 80% and an alpha level of 0.05 using a two-tailed t-test of two independent samples.

Fig. 1.

A schematic of a femoral condyle plug defect is shown.

A μCT 50 scanner (SCANCO Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) was used to acquire images of the extracted femurs at 16 weeks and cured low-viscosity grafts (n = 4) fabricated independent of the in vivo study. μCT scans were performed in 10% neutral buffered formalin at 70 kVp energy, 200 μA source current, 1000 projections per rotation, 800 ms integration time, and an isotropic voxel size of 24.2 μm. Four concentric annular volumes of interest 1.83 mm thick and 14 mm long (from the outer cortical surface of the femur) were defined for each sample. The three inner regions incorporated the composites, whereas the outer region included the host bone interface. Ossified tissue was segmented using a threshold of 340 mg hydroxyapatite per cm−3 to include new bone and ceramic as reported previously [13, 37]. Bone volume fraction (bone volume/total volume), trabecular separation, trabecular number, and trabecular thickness were measured for each annular region and plotted versus the mean radial distance from the core of the defect (Rm) [13, 37]. These morphometric parameters were chosen to quantitatively assess the remodeling of trabecular bone architecture in three dimensions assuming a fixed-structure model [5]. Measured values of morphometric parameters for treated defects were compared with published values for ovine femur trabecular bone to assess healing [2, 31].

Sheep femora were maintained in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 3 weeks after dehydration in ethanol. Specimens were embedded in polymethylmethacrylate and longitudinal cross-sections were cut, ground, and polished (< 100 μm) in the middle of the defect from the blocks using an Exakt system (Exakt Technologies Inc, Norderstedt, Germany). Sections were stained with Stevenel’s Blue and Van Gieson’s and imaged at ×2 and ×20 magnification with an Olympus DP71 camera and SZX16 microscope (Olympus Corp, Tokyo, Japan). New bone formation and residual ceramic were quantified based on color analysis from one slide per defect (two data points per slide) using MetaMorph® software (Version 7.0.1) in an area of interest (6 × 14.6 mm) located in the center of the defect [13, 14, 37]. The rectangular area of interest was subdivided in regions 1.83 mm wide corresponding to the size and location of the μCT regions of interest [13, 37]. For μCT morphometric parameters and histomorphometry data, statistical significance was assessed by a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test, post hoc, for both regions of interest and treatment groups.

Results

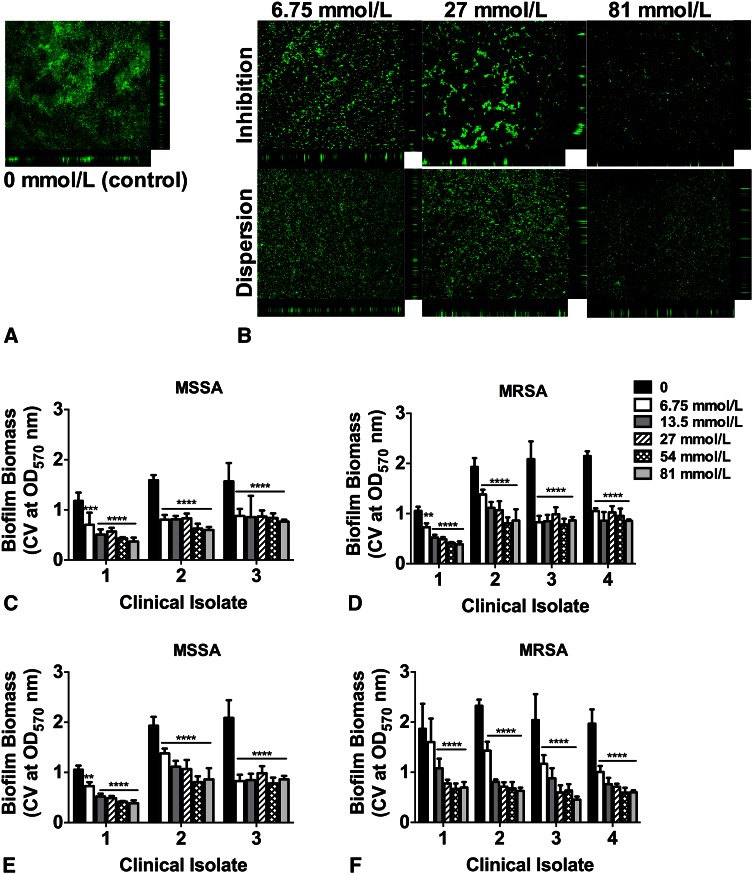

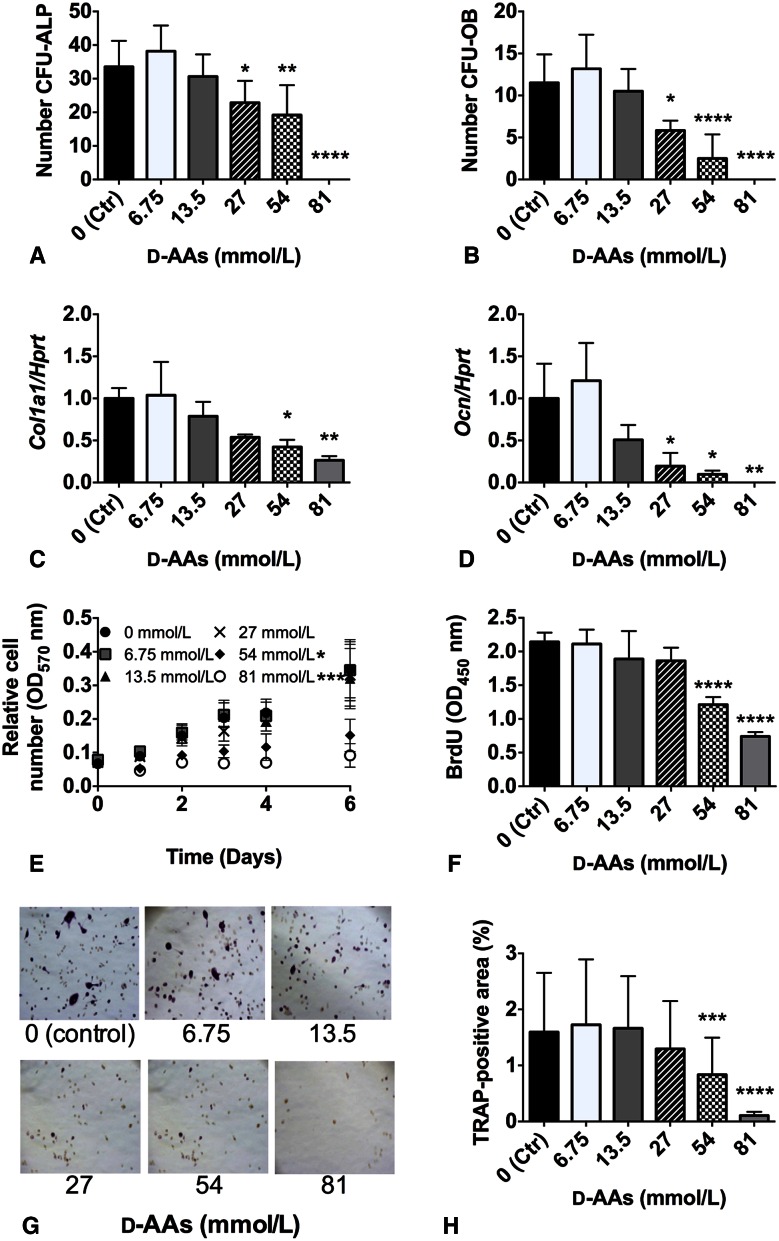

d-AAs inhibited biofilm formation, BMSC proliferation, osteoblast differentiation, and osteoclast differentiation in a dose-responsive manner in vitro. Biofilm biomass decreased when MRSA and MSSA clinical isolates were exposed to d-AA concentrations of 13.5 mmol/L or greater (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). The number of CFU-ALP (Fig. 3A) and CFU-OB (Fig. 3B) colonies decreased when osteoblasts were exposed to d-AA concentrations of 27 mmol/L or greater (p < 0.05). Expression of the osteogenic genes Col1a1 (Fig. 3C) and Ocn (Fig. 3D) decreased when osteoblasts were treated with d-AA concentrations of 54 mmol/L or greater (p < 0.05) and 27 mmol/L or greater, respectively (p < 0.05). Exposure of BMSCs to d-AA concentrations of 54 mmol/L or greater (p < 0.05) inhibited proliferation (Fig. 3E–F). The effect of d-AAs on osteoclast precursor cell differentiation was evaluated by TRAP staining (Fig. 3G). The percent area positively stained for TRAP in osteoclast cultures decreased when cells were exposed to d-AAs concentrations of 54 mmol/L or greater (p < 0.001, Fig. 3H). d-AA concentrations of 50 mmol/L or greater have been reported to inhibit biofilms in vivo [41]. Although it is difficult to directly compare in vitro and in vivo concentrations owing to differences in release kinetics and unknown retention at the defect site, these results suggest that d-AAs inhibit biofilm formation at concentrations (≥ 13.5 mmol/L) lower than those at which they inhibit osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis (≥ 27 mmol/L).

Fig. 2A–F.

The images show inhibition and dispersion of bacterial biofilm formation of a representative clinical isolate of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (strain SAMMC 41) after exposure to (A) 0 mmol/L d-AAs and (B) 6.75 mmol/L or more d-AAs. Quantification of inhibition of established biofilms from clinical isolates of (C) methicillin-susceptible S aureus (MSSA) and (D) MRSA after exposure to d-AAs shows dose-responsive behavior in a range of 0 to 81 mmol/L. Quantification of dispersion of established biofilms from clinical isolates of (E) MSSA and (F) MRSA after exposure to d-AAs shows dose-responsive behavior with a range of 0 to 81 mmol/L. The values are representative of the mean ± SD of four samples. **, ***, and **** = significant differences compared with the control (p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively) as determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, post hoc. CV = crystal violet; OD = optical density.

Fig. 3A–H.

The dose-dependent inhibitory effect of d-amino acids (d-AAs) on bone marrow osteoblast differentiation was shown by the numbers of (A) alkaline phosphatase-positive colony forming units (CFU-ALP) and (B) osteoblast colony-forming units (CFU-OB) in osteogenic medium supplemented with d-AA concentrations from 0 to 81 mmol/L (values are reported as mean ± SD from three independent repeats with duplicates per each repeat). The osteoblast-specific gene expression of (C) Col1a1 and (D) Ocn (values are reported as mean ± SD from three independent repeats) is shown. The dose-dependent inhibitory effect of d-AAs on bone marrow stromal cell (BMSC) proliferation was shown by (E) cell number (OD570) of BMSCs treated with d-AAs (0–81 mmol/L) for 6 days (reported as mean ± SD from five independent repeats); and (F) bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (determined by OD450) of BMSCs treated with a series of d-AAs (reported as mean ± SD from three independent repeats with duplicates per each repeat). The dose-dependent inhibitory effect of d-AAs on osteoclast differentiation was shown by (G) representative images and (H) corresponding percentage tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive surface area of osteoclast cultures treated with d-AA concentrations 0 to 81 mmol/L (reported as mean ± SD from four independent repeats with four images per treatment taken for each repeat). *, **, ***, and **** = significant differences compared with the control (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively) as determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, post hoc. Ctr = control; OD = optical density; Col1a1 = collagen, type I, alpha 1; HPRT = hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase; Ocn = osteocalcin.

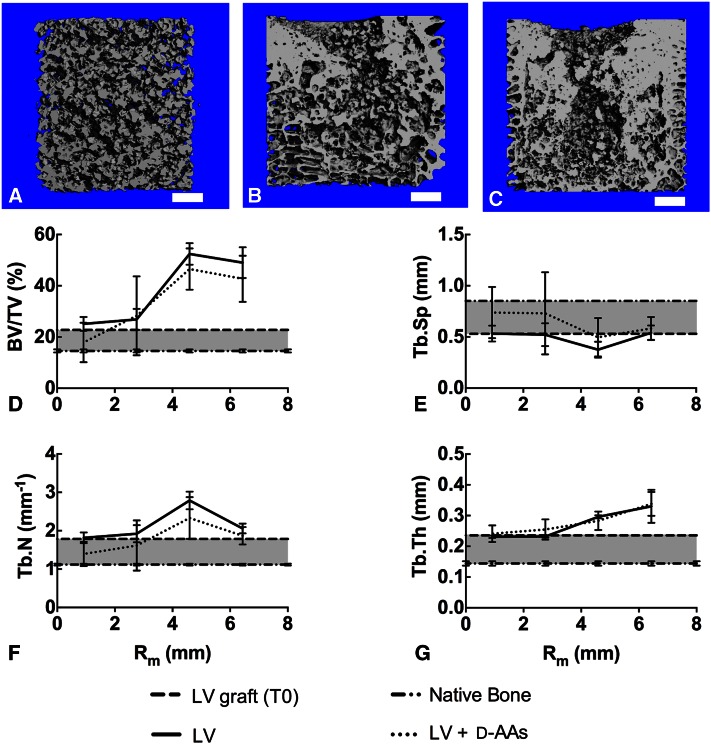

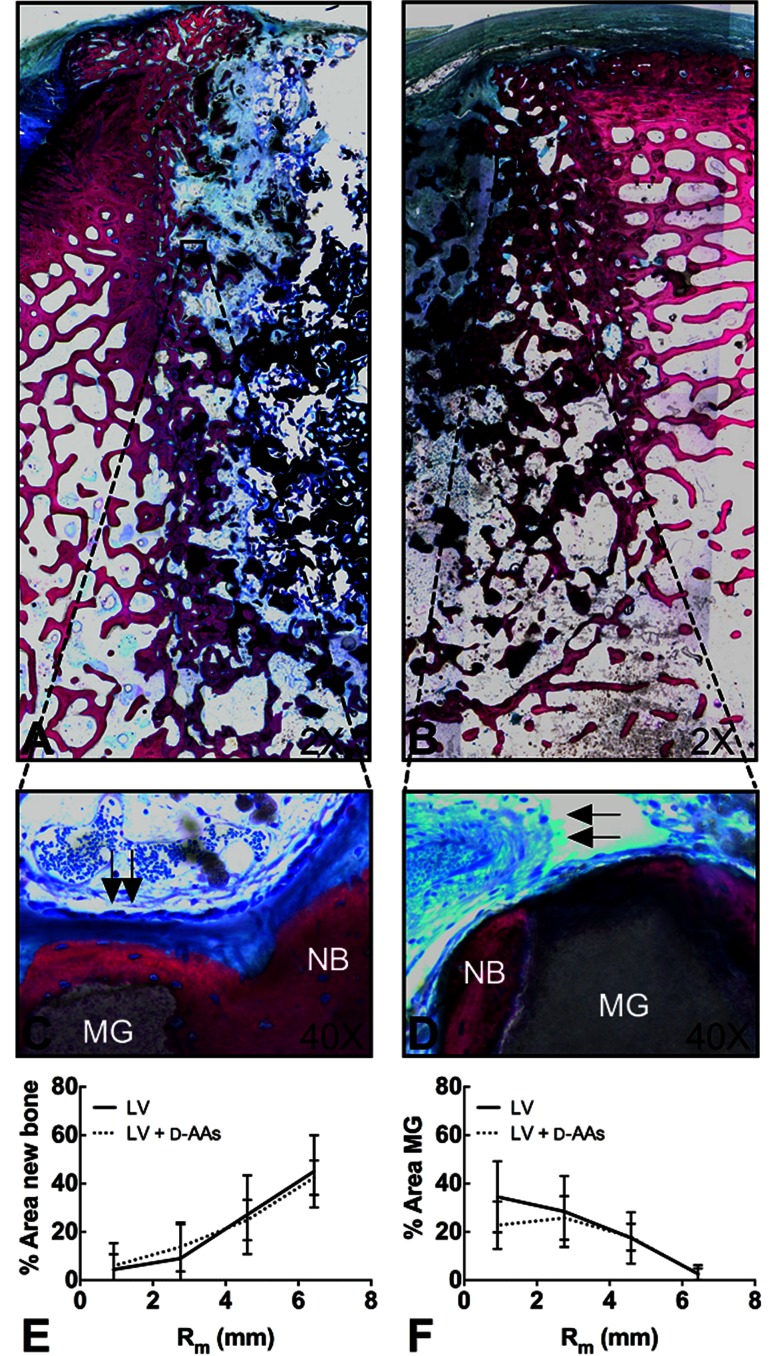

Local delivery of d-AAs from low-viscosity grafts did not inhibit new bone formation in a large-animal model pilot study. The primary end point was bone volume/total volume in the middle region of the graft (Rm = 2.76 mm: 0 mmol/L d-AAs: bone volume/total volume = 26.9% ± 4.1%; 200 mmol/L d-AAs: bone volume/total volume = 28.3% ± 15.4%; mean difference with 95% CI = −1.4; p = 0.13), which previous studies have suggested has substantially remodeled at this time [13, 37]. Representative three-dimensional μCT images of low viscosity before in vivo implantation (Fig. 4A) compared with femoral condyle plug defects treated with low viscosity ± d-AAs at 16 weeks after implantation (Fig. 4B–C) showed mineral content noncharacteristic of ceramic particles alone, indicating new bone formation and remodeling at the outer region of the defect site (as compared with the inner region) for both groups. Bone volume/total volume (which includes new bone and residual ceramic particles) for each region approached or exceeded that of the low-viscosity graft at Time 0 (dashed line, Fig. 4D) and native bone in a nongrafted femur (dotted-dashed line, Fig. 4D). Densification of the bone near the graft interface was observed, as evidenced by the higher value of bone volume/total volume for Rm greater than 4 mm. The morphometric parameters, trabecular separation (Fig. 4E), and trabecular number (Fig. 4F) showed small differences between treatment groups and radial location. Trabecular thickness showed small differences between treatment groups and increased monotonically with Rm (Fig. 4G). Histologic sections of defects treated with low viscosity ± d-AAs at 16 weeks after implantation showed mainly fibrous cellular infiltration with histologic signs of active bone formation (Fig. 5A–B). At the margins (bone-graft interface), densification of the bone was observed, as described above. Low-magnification images (× 2, Fig. 5A–B) of the defect sites showed residual ceramic particles (black) and new bone (pink) formation at the outer regions for both test groups. There was minimal evidence of residual polymer (turquoise). In addition, the morphologic features of the surrounding host trabecular bone were similar for both groups. Defects filled in both test groups showed similar osteocyte densities throughout mineralized bone (new and surrounding host bone) and some signs of fibrous tissue near the center of defect sites. High-magnification images (× 20, Fig. 5C–D) showed new mineralized bone formation along the MASTERGRAFT® particle surface, active cuboidal-shaped osteoblasts along bone surfaces, and blood vessels filled with erythrocytes. Radial histomorphometric analysis showed no differences in new bone formation (Fig. 5E) (0 mmol/L d-AAs: area % new bone = 9.1% ± 14.1%; 200 mmol/L d-AAs: area % new bone = 13.8% ± 10.2%; mean difference with 95% CI = −4.7; p = 0.90) or ceramic resorption (Fig. 5F)(0 mmol/L d-AAs: area % ceramic = 28.4% ± 14.7%; 200 mmol/L d-AAs: area % ceramic = 25.8% ± 9.1%; mean difference with 95% CI = 2.7; p = 0.15) in the middle region of the graft (Rm = 2.76 mm). New bone formation increased and residual ceramic decreased with increasing Rm.

Fig. 4A–G.

Representative μCT three-dimensional reconstructions (scale bars = 2 mm) for the (A) low-viscosity (LV) graft before in vivo implantation and defects filled with (B) LV or (C) LV + d-amino acids (d-AAs) at 16 weeks show similar morphologic features throughout the defect site and increased density at the graft-host bone interface. The morphologic parameters, (D) bone volume/total volume (BV/TV), (E) trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), (F) trabecular number (Tb.N), and (G) trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) plotted versus the mean radius of the region of interest (Rm) show minimal differences between defects filled with low viscosity graft or low viscosity + d-AAs. Plotted controls included the mean of each parameter for native femur trabecular bone and low-viscosity graft before in vivo implantation (T0). Values are mean ± SD of four samples. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, post hoc.

Fig. 5A–F.

Half-view (of entire slide analyzed) low- (×2) magnification images of histologic cross-sections of defects filled with (A) low-viscosity (LV) or (B) LV+ d-amino acids (d-AAs) at 16 weeks show active remodeling. Sections were stained with Stevenel’s Blue and Van Gieson. Corresponding high- (×40) magnification images of highlighted portions of defects filled with (C) LV or (D) LV+ d-AAs show residual MASTERGRAFT® (MG) ceramic particles, new bone (NB), and vascular development (arrows). Area % (E) new bone and (F) MG at four regions in the defect measured by histomorphometric analysis show minimal differences in new bone formation or MASTERGRAFT® degradation between LV and LV+ d-AAs. Values are mean ± SD of eight samples per region. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, post hoc.

Discussion

Bone grafts implanted in contaminated open fractures can function as a nidus for infection owing to formation of a biofilm on the surface [41]. Antibiotic treatment needed to eliminate sessile bacteria in biofilms requires concentrations more than 500 times those required to kill planktonic bacteria [12]. Although local delivery of antibiotics can achieve bactericidal concentrations, many clinically used antibiotics, including rifampin, doxycycline, and penicillin, are either cytotoxic or inhibit osteogenic differentiation in vitro at therapeutically relevant concentrations [39]. Alternatives to antibiotics include agents that have inhibitory and/or dispersive activity against biofilms such as bismuth thiols [17], recombinant DNAses [25], quorum-sensing inhibitors [22], and d-AAs [3, 26, 41], which have been reported to disperse biofilms in vitro and improve healing of biofilm-associated infections in vivo [7, 46]. d-AAs are active against a broad spectrum of bacterial species, and local delivery of d-AAs from bone grafts has been shown to reduce the frequency of infection of open fractures contaminated with S aureus in vivo [41]. However, the effects of d-AA concentration on osteocompatibility are the subject of debate, with one study reporting that 250 to 500 µmol/L of a d-Pro: d-Tyr: d-Phe mixture reduced BMSC viability and ALP expression [40] and another reporting that d-Met, d-Pro, and d-Phe were noncytotoxic to human osteoblasts at concentrations less than 50 mmol/L [41]. Thus, the goal of our study was to evaluate the effect of d-AAs on bone cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro and new bone formation in vivo.

A limitation of this pilot study is that in vivo bone healing was evaluated at only one time. Four months was selected in response to an FDA guidance document [51] for bone void fillers, which requires a study of sufficient duration to observe new bone formation and graft resorption. Evaluating new bone formation at a point during which d-AAs are being released (< 1 month) is challenging owing to the limited amount of new bone formed at this early time. At 4 months, local delivery of 200 mmol/L d-Phe:d-Pro:d-Met mixture did not inhibit new bone formation. For low-viscosity scaffolds without ceramic, the burst release of d-AAs ranged from 20% to 60%, and greater than 95% of the drug was released during the first 30 days [41]. It is possible that the ceramic component delayed the release of the d-AAs in our study, although the near-complete degradation of the polymer at 4 months suggests that release of the drug was complete by this late time. A second limitation of this study was the inability to distinguish new bone from residual MASTERGRAFT® through μCT owing to their similar densities. Histologic and histomorphometric radial analyses (Fig. 4E–F) were done in addition to μCT to independently quantify the area percent new bone and MASTERGRAFT®. We used an established ovine critical-size femoral defect [10] to answer the question whether local delivery of d-AAs inhibits new bone formation. To reduce the use of animals, a negative control (empty defect) was not used as this defect will not heal without grafting.

Another limitation of this pilot study was the small sample size. The low-viscosity control showed bone volume/total volume of 26.9% ± 4.1% in the middle region of the defect, which is close to the assumptions of our power calculation (bone volume/total volume = 30% ± 5%). However, the low-viscosity + d-AAs group showed bone volume/total volume of 28.3% ± 15.4%. The lower amount of ceramic (40 versus 45 weight %) in the low-viscosity + d-AAs group may account for the increased variability as new bone was observed to be growing predominantly during the ceramic phase, which is consistent with a previous study investigating osteoconductive ceramics [52].

A 1:1:1 mixture of d-Met:d-Pro:d-Phe inhibited S aureus biofilms at concentrations of 13.5 mmol/L or greater, which is consistent with a previous study investigating a 1:1:1 mixture of d-Met:d-Pro:d-Trp [41]. d-AA concentrations of 27 mmol/L or greater inhibited osteogenesis and osteoclastogenesis. Thus, our findings indicate that d-AAs exhibit antibiofilm activity at concentrations below levels that hinder osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation in vitro. The d-Met:d-Pro:d-Trp inhibited biofilm formation in a contaminated rat segmental defect model at concentrations of 50 to 100 mmol/L [41]. To provide a stringent test, the effects of 200 mmol/L d-AAs (twofold to fourfold greater than concentrations required to inhibit biofilms in vivo) on new bone formation were investigated in a large animal model.

Low-viscosity grafts were augmented with d-AAs and injected in ovine femoral condyle plug defects to assess their effect on bone healing in vivo. As shown by μCT (Fig. 4) and histologic (Fig. 5) analyses, an increase in bone volume/total volume and area percent new bone was observed at the outer region of both groups receiving the low-viscosity grafts (Rm > 4 mm). Thus, bone ingrowth started near the host bone/composite interface and progressed toward the interior of the composite, as evidenced by the increase in bone volume/total volume near the interface and monotonic decrease in bone volume/total volume from the interface to the inner core. This mechanism differs from the remodeling of polymer/allograft bone composites implanted in rabbit femoral plug defects, which exhibited bone volume/total volume values closer to that of host bone near the interface [13, 37]. This difference in bone ingrowth may be the result of differences in porosity between the low-viscosity grafts (27%–28%) and allograft (2%–6%) [13, 37] composites. Thus, the higher porosity of low-viscosity grafts may have supported faster cellular infiltration compared with low-porosity allograft composites.

Sustained release of antibiotics at concentrations exceeding the minimal bacterial concentration is required for at least 4 weeks to control infection of contaminated bone defects [29], but the optimal concentration and duration of release for biofilm dispersal agents are unknown. Longitudinal studies investigating bacterial burden, bone formation, and bone remodeling in contaminated defects [34] as a function of d-AA dose and release kinetics during healing are needed to further support the use of d-AAs in the clinical management of infected open fractures.

Footnotes

The institution of one or more of the authors (SAG, FE, JCW) has received, during the study period, funding from the Orthopaedic Extremity Trauma Research Program (SAG and JCW), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (SAG, JCW, and FE), Medtronic, Inc (SAG); Oak Ridge Institute (AJH); and the National Institutes of Health (SAG).

One of the authors certifies that he (SAG), or a member of his or her immediate family, has or may receive payments or benefits, during the study period, an amount less than USD 10,000, from Medtronic Spine and Biologics (Memphis, TN, USA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the animal protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

The sheep study was performed at IBEX Preclinical Research (Logan, UT, USA). The in vitro studies were performed at the US Army Institute of Surgical Research (San Antonio, TX, USA). Micro-CT and histology were performed at Vanderbilt University (Nashville, TN, USA).

References

- 1.Barei DP, Nork SE, Mills WJ, Henley MB, Benirschke SK. Complications associated with internal fixation of high-energy bicondylar tibial plateau fractures utilizing a two-incision technique. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18:649–657. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bindl R, Oheim R, Pogoda P, Beil FT, Gruchenberg K, Reitmaier S, Wehner T, Calcia E, Radermacher P, Claes L, Amling M, Ignatius A. Metaphyseal fracture healing in a sheep model of low turnover osteoporosis induced by hypothalamic-pituitary disconnection (HPD) J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1851–1857. doi: 10.1002/jor.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottcher T, Kolodkin-Gal I, Kolter R, Losick R, Clardy J. Synthesis and activity of biomimetic biofilm disruptors. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:2927–2930. doi: 10.1021/ja3120955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bost KL, Ramp WK, Nicholson NC, Bento JL, Marriott I, Hudson MC. Streptococcus aureus infection of mouse or human osteoblasts induces high levels of interleukin-6 and interleukin-12 production. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1912–1920. doi: 10.1086/315138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouxsein ML, Boyd SK, Christiansen BA, Guldberg RE, Jepsen KJ, Müller R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro–computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1468–1486. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyum A. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood isolation of mononuclear cells by one centrifugation and of granulocytes by combining centrifugation and sedimentation at 1 g. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1968;97:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brackman G, Cos P, Maes L, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Quorum sensing inhibitors increase the susceptibility of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2655–2661. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00045-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandenburg KS, Rodriguez KJ, McAnulty JF, Murphy CJ, Abbott NL, Schurr MJ, Czuprynski CJ. Tryptophan inhibits biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1921–1925. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00007-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns TC, Stinner DJ, Mack AW, Potter BK, Beer R, Eckel TT, Possley DR, Beltran MJ, Hayda RA, Andersen RC, Keeling JJ, Frisch HM, Murray CK, Wenke JC, Ficke JR, Hsu JR, Skeletal Trauma Research Consortium Microbiology and injury characteristics in severe open tibia fractures from combat. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1062–1067. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318241f534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coathup MJ, Cai Q, Campion C, Buckland T, Blunn GW. The effect of particle size on the osteointegration of injectable silicate-substituted calcium phosphate bone substitute materials. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2013;101:902–910. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conterno LO, Turchi MD. Antibiotics for treating chronic osteomyelitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD004439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004439.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costerton JW, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell DE, Korber DR, Lappin-Scott HM. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dumas JE, Prieto EM, Zienkiewicz KJ, Guda T, Wenke JC, Bible J, Holt GE, Guelcher SA. Balancing the rates of new bone formation and polymer degradation enhances healing of weight-bearing allograft/polyurethane composites in rabbit femoral defects. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:115–129. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dumas JE, Zienkiewicz K, Tanner SA, Prieto EM, Bhattacharyya S, Guelcher S. Synthesis and characterization of an injectable allograft bone/polymer composite bone void filler with tunable mechanical properties. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2505–2518. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elefteriou F, Exposito JY, Garrone R, Lethias C. Characterization of the bovine tenascin-X. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22866–22874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ercal N, Luo X, Matthews RH, Armstrong DW. In vitro study of the metabolic effects of D-amino acids. Chirality. 1996;8:24–29. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1996)8:1<24::AID-CHIR6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folsom JP, Baker B, Stewart PS. In vitro efficacy of bismuth thiols against biofilms formed by bacteria isolated from human chronic wounds. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;111:989–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillies RJ, Didier N, Denton M. Determination of cell number in monolayer cultures. Anal Biochem. 1986;159:109–113. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gopal S, Majumder S, Batchelor AG, Knight SL, De Boer P, Smith RM. Fix and flap: the radical orthopaedic and plastic treatment of severe open fractures of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:959–966. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B7.10482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guelcher SA, Brown KV, Li B, Guda T, Lee BH, Wenke JC. Dual-purpose bone grafts improve healing and reduce infection. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25:477–482. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31821f624c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hafeman AE, Li B, Yoshii T, Zienkiewicz K, Davidson JM, Guelcher SA. Injectable biodegradable polyurethane scaffolds with release of platelet-derived growth factor for tissue repair and regeneration. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2387–2399. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9618-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hentzer M, Givskov M. Pharmacological inhibition of quorum sensing for the treatment of chronic bacterial infections. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1300–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI20074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochbaum AI, Kolodkin-Gal I, Foulston L, Kolter R, Aizenberg J, Losick R. Inhibitory effects of D-amino acids on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm development. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:5616–5622. doi: 10.1128/JB.05534-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson EN, Burns TC, Hayda RA, Hospenthal DR, Murray CK. Infectious complications of open type III tibial fractures among combat casualties. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:409–415. doi: 10.1086/520029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan JB, LoVetri K, Cardona ST, Madhyastha S, Sadovskaya I, Jabbouri S, Izano EA. Recombinant human DNase I decreases biofilm and increases antimicrobial susceptibility in staphylococci. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2012;65:73–77. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolodkin-Gal I, Romero D, Cao S, Clardy J, Kolter R, Losick R. D-amino acids trigger biofilm disassembly. Science. 2010;328:627–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1188628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leiman SA, May JM, Lebar MD, Kahne D, Kolter R, Losick R. D-amino acids indirectly inhibit biofilm formation in Bacillus subtilis by interfering with protein synthesis. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:5391–5395. doi: 10.1128/JB.00975-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369–379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Brown KV, Wenke JC, Guelcher SA. Sustained release of vancomycin from polyurethane scaffolds inhibits infection of bone wounds in a rat femoral segmental defect model. J Control Release. 2010;145:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y, Krueger JJ, Redmon SN, Uppuganti S, Nyman JS, Hahn MK, Elefteriou F. Extracellular norepinephrine clearance by the norepinephrine transporter is required for skeletal homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:30105–30113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.481309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mittra E, Rubin C, Qin YX. Interrelationship of trabecular mechanical and microstructural properties in sheep trabecular bone. J Biomech. 2005;38:1229–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray CK, Obremskey WT, Hsu JR, Andersen RC, Calhoun JH, Clasper JC, Whitman TJ, Curry TK, Fleming ME, Wenke JC, Ficke JR, Prevention of Combat-Related Infections Guidelines Panel Prevention of infections associated with combat-related extremity injuries. J Trauma. 2011;71(2 suppl 2):S235–S257. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318227ac5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muzylak M, Arnett TR, Price JS, Horton MA. The in vitro effect of pH on osteoclasts and bone resorption in the cat: implications for the pathogenesis of FORL. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:144–150. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niska JA, Meganck JA, Pribaz JR, Shahbazian JH, Lim E, Zhang N, Rice BW, Akin A, Ramos RI, Bernthal NM, Francis KP, Miller LS. Monitoring bacterial burden, inflammation and bone damage longitudinally using optical and mCT imaging in an orthopaedic implant infection in mice. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer M, Costerton W, Sewecke J, Altman D. Molecular techniques to detect biofilm bacteria in long bone nonunion: a case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:3037–3042. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1843-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penn-Barwell JG, Bennett PM, Fries CA, Kendrew JM, Midwinter MJ, Rickard RF. Severe open tibial fractures in combat trauma: management and preliminary outcomes. Bone Joint J. 2013;95:101–105. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B1.30580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prieto EM, Talley AD, Gould NR, Zienkiewicz KJ, Drapeau SJ, Kalpakci KN, Guelcher SA. Effects of particle size and porosity on in vivo remodeling of settable allograft bone/polymer composites. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2015 Jan 8. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ramon-Perez ML, Diaz-Cedillo F, Ibarra JA, Torales-Cardena A, Rodriguez-Martinez S, Jan-Roblero J, Cancino-Diaz ME, Cancino-Diaz JC. D-Amino acids inhibit biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis strains from ocular infections. J Med Microbiol. 2014;63:1369–1376. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.075796-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rathbone CR, Cross JD, Brown KV, Murray CK, Wenke JC. Effect of various concentrations of antibiotics on osteogenic cell viability and activity. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1070–1074. doi: 10.1002/jor.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rawson M, Haggard W, Jennings JA. Osteocompatibility of biofilm inhibitors. Open Orthop J. 2014;8:442–449. doi: 10.2174/1874325001408010442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez CJ, Jr, Prieto EM, Krueger CA, Zienkiewicz KJ, Romano DR, Ward CL, Akers KS, Guelcher SA, Wenke JC. Effects of local delivery of D-amino acids from biofilm-dispersive scaffolds on infection in contaminated rat segmental defects. Biomaterials. 2013;34:7533–7543. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schierle CF, De la Garza M, Mustoe TA, Galiano RD. Staphylococcal biofilms impair wound healing by delaying reepithelialization in a murine cutaneous wound model. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:354–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah SN, Karunakar MA. Early wound complications after operative treatment of high energy tibial plateau fractures through two incisions. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah SR, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Perspectives on the prevention and treatment of infection for orthopedic tissue engineering applications. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2013;58:4342–4348. doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-5780-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah SR, Tatara AM, D’Souza RN, Mikos AG, Kasper FK. Evolving strategies for preventing biofilm on implantable materials. Materials Today. 2013;16:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2013.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simonetti O, Cirioni O, Ghiselli R, Goteri G, Scalise A, Orlando F, Silvestri C, Riva A, Saba V, Madanahally KD, Offidani A, Balaban N, Scalise G, Giacometti A. RNAIII-inhibiting peptide enhances healing of wounds infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2205–2211. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01340-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smucker JD, Petersen EB, Fredericks DC. Assessment of MASTERGRAFT PUTTY as a graft extender in a rabbit posterolateral fusion model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:1017–1021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Somayaji SN, Ritchie S, Sahraei M, Marriott I, Hudson MC. Staphylococcus aureus induces expression of receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand and prostaglandin E-2 in infected murine osteoblasts. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5120–5126. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00228-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabel G, Hoa NT, Tarnawski A, Chen J, Domek M, Ma TY. Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits healing of the wounded duodenal epithelium in vitro. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;142:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tuomanen E, Cozens R, Tosch W, Zak O, Tomasz A. The rate of killing of Escherichia coli by beta-lactam antibiotics is strictly proportional to the rate of bacterial-growth. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:1297–1304. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-5-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff - Class II Special Controls Guidance Document: Resorbable Calcium Salt Bone Void Filler Device. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm072704.htm. Accessed July 10, 2015.

- 52.Wakimoto M, Ueno T, Hirata A, Iida S, Aghaloo T, Moy PK. Histologic evaluation of human alveolar sockets treated with an artificial bone substitute material. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:490–493. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318208bacf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wenke JC, Guelcher SA. Dual delivery of an antibiotic and a growth factor addresses both the microbiological and biological challenges of contaminated bone fractures. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8:1555–1569. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.628655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winkler T, Hoenig E, Gildenhaar R, Berger G, Fritsch D, Janssen R, Morlock MM, Schilling AF. Volumetric analysis of osteoclastic bioresorption of calcium phosphate ceramics with different solubilities. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4127–4135. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xing SF, Sun XF, Taylor AA, Walker SL, Wang YF, Wang SG. D-Amino acids inhibit initial bacterial adhesion: thermodynamic evidence. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:696–704. doi: 10.1002/bit.25479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang H, Wang M, Yu J, Wei H. Aspartate inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2015;362. DOI: 10.1093/femsle/fnv025. [DOI] [PubMed]