Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is an opportunistic Gram-negative pathogen associated with nosocomial infections, acute infections and chronic lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. The ability of PA to cause infection can be attributed to its ability to adapt to a multitude of environments. Modification of the lipid A portion of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a vital mechanism Gram-negative pathogens use to remodel the outer membrane in response to environmental stimuli. Lipid A, the endotoxic moiety of LPS, is the major component of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria making it a critical factor for bacterial adaptation. One way PA modifies its lipid A is through the addition of laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate. This secondary or late acylation is carried out by the acyltransferase, HtrB (LpxL). Analysis of the PA genome revealed the presence of two htrB homologs, PA0011 (htrB1) and PA3242 (htrB2). In this study, we were able to show that each gene identified is responsible for site-specific modification of lipid A. Additionally, deletions of either gene altered resistance to specific classes of antibiotics, cationic antimicrobial peptides and increased membrane permeability suggesting a role for these enzymes in maintaining optimal membrane organization and integrity.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, LPS, acyltransferase, membrane remodeling, HtrB, lipid A

Modification of the lipid A portion of lipopolysaccharide through altered acylation is a vital mechanism Gram-negative pathogens use to remodel the outer membrane in response to environmental stimuli.

Graphical Abstract Figure.

Modification of the lipid A portion of lipopolysaccharide through altered acylation is a vital mechanism Gram-negative pathogens use to remodel the outer membrane in response to environmental stimuli.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) is a Gram-negative, motile bacterium found extensively in water and soil. This opportunistic pathogen can cause a variety of acute and chronic illnesses, such as eye and ear infections, burn wound infections, pneumonia and airway infections of patients with cystic fibrosis. The ability of this organism to cause both acute and chronic disease lies in the ability of PA to rapidly sense its environment and remodel its outer membrane to evade the host innate immune response through modification of its lipid A. Lipid A comprises the outer most membrane of the cell envelope and is the portion of the LPS molecule responsible for endotoxin activity in the host. Highly conserved enzymes synthesize the base lipid A molecule, commencing on the inner membrane before transport to the outer leaflet of the inner membrane. PA has the ability to synthesize complex lipid A species with a variety of fatty acid substitutions (4–7 acyl groups), as well as species with carbohydrate modifications attached to the terminal phosphates.

Lipid A biosynthesis in Escherichia coli is initiated on the inner leaflet of the inner membrane resulting in the production of a bisphosphorylated, tetraacylated lipid A structure. Subsequently, late or secondary acyl-oxo-acyl additions to lipid A are made to the glucosamine backbone at the 2′ and 3′ positions by the acyltransferase HtrB (LpxL) (Brozek and Raetz 1990; Clementz, Bednarski and Raetz 1996) and MsbB (LpxM) (Clementz, Zhou and Raetz 1997), respectively. The HtrB enzyme mediates the addition of laurate (C12:0 fatty acid), while MsbB adds a myristate (C14:0 fatty acid). These are among the last modifications made before lipid A transport to the outer membrane. PA is unique in that it adds two 12-carbon secondary fatty acids, a 2-hydroxylaurate (2-OH C12) and laurate moiety to the base lipid A structure. The addition of the 2 position hydroxylation is believed to be mediated by an additional enzyme LpxO, which has previously been identified to add hydroxylation to the lipid A of other bacterial species (Gibbons et al. 2000; MacArthur et al. 2011) This is followed by removal of the 3-OH C10 fatty acid residue at the 3 position to yield the predominate lipid A structure for PA (Fig. 1). The exact position of the laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate and the enzyme(s) responsible for these modifications were unknown. Using the htrB gene sequence from E. coli, we performed a homology search to identify possible htrB homologs in PA. This analysis revealed the presence of two homologs of the E. coli htrB gene; PA0011, designated htrB1, and PA3242, designated htrB2. Analysis of lipid A purified from ΔhtrB1 and ΔhtrB2 mutants showed that each enzyme adds a given fatty acid in a site-specific manner.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of PA lipid A. Initial modifications to the tetraacylated lipid A molecule include the addition of laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate. Removal of the 3 position 3-hydroxydecanoate results in the highest abundance PA lipid A species.

Inhibition of one or more enzymes involved in lipid A modification has been shown to alter membrane remodeling in multiple bacterial species. Deletion of htrB in E. coli inhibited growth above 33°C in rich medium (Karow and Georgopoulos 1991; Karow et al. 1991) resulted in filamentous or bulging morphology (Karow et al. 1991), increased susceptibility to antibiotics (Karow and Georgopoulos 1992; Lee et al. 1995) and decreased ability to colonize human airway epithelium (Swords et al. 2002). As stated before, lipid A is synthesized in the inner membrane and transported to the outer leaflet of the outer membrane. This observed decrease in fitness of the E. coli htrB mutant was partially attributed to the loss of optimal transport of lipid A across the inner membrane due to altered binding within the transport machinery resulting in a compromised outer membrane (Zhou et al. 1998). Factors such as decreased membrane stability and altered protein incorporation are also thought to be contributing factors.

The role these modification enzymes can play in infection and general bacterial survival influenced the focus of this work on defining the biosynthesis of PA lipid A with a specific emphasis on the role(s) for laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate. We are able to show for the first time the presence of two HtrB enzymes with site-specific functions. Additionally, each of these enzymes was shown to influence antimicrobial resistance and alter membrane permeability providing further evidence of the potential importance of these enzymes during infection.

METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions, strains and gene deletions

Pseudomonas aeruginosa was grown in Lysogenic broth (LB) supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2 to suppress lipid A modifications regulated by the two-component system PhoP/Q. Complimented strains were grown in LB containing carbenicillin (200 μg ml−1) supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2.

Recombinant DNA techniques

Plasmids and strains used in these studies are shown in Table S1 (Supporting Information) and primers used in Table S2 (Supporting Information). Genetic deletions were generated in the laboratory-adapted PA strain, PAK, using the Gateway Cloning System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Clean deletions of PA0011 and PA3242 with the first and last three amino acids retained were engineered using short flanking regions of each gene generated from genomic DNA by PCR with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, the PCR fragments were first cloned into the Gateway-compatible vector pDONR201 using BP Clonase II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The resulting product was then introduced into E. coli DH5α cells by heat shock, and the bacterial transformants were selected on plates containing kanamycin (50 μg ml−1). The PCR fragments were subsequently introduced into the broad-host-range plasmid pEXGW-D using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The plasmid was then introduced into PAK by 10-min electroporation protocol (Choi, Kumar and Schweizer 2006). The resulting merodiploids were formed via the integration of suicide plasmid by a single crossover event. The merodiploid state was then resolved via sucrose selection in the presence of gentamycin, resulting in deletion of the wild-type (WT) gene. Deletions were confirmed by sequencing using primers 1 and 4 for each gene of interest.

Complementation was performed using the USER vector and USER Friendly Cloning Kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). The entire gene encoded by PA0011 or PA3242 was PCR amplified with primers containing the USER flanking sites and subsequently ligated into pUCP19-USER. The resulting plasmids were electroporated and introduced into PA by 10-min electroporation protocol (Choi, Kumar and Schweizer 2006). The transformants were then selected on plates containing carbenicillin (200 μg ml−1).

Bacterial growth curves

Testing for growth defects was carried out by growing WT, mutant and complemented strains in LB supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2 in a 96-well plate. Samples were incubated in a DTX-880 Multimode Plate Reader (Beckman Coulter, IN, Indiana) shaking at 25, 37 or 42°C. Absorbance readings were taken every 15 min for 16 h at 600 nm. Three replicates were done for each strain at all temperatures tested. The average of the three was used for points on the curve.

LPS and lipid A isolation

LPS was extracted by the hot phenol/water method (Westphal and Jann 1965). Freeze-dried bacterial pellets were resuspended in endotoxin-free water at a concentration of 10 mg ml−1. A volume of 12.5 ml of 90% phenol (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) was added and the resultant mixture was vortexed and incubated for 60 min in a hybridization oven at 65°C. The mixture was cooled on ice and centrifuged at 12 096 × g at room temperature for 30 min. The aqueous phase was collected and an equal volume of endotoxin-free water was added to the organic phase. The extraction was repeated and aqueous phases were combined and dialyzed against Milli-Q purified water to remove residual phenol and then freeze-dried. The resultant pellet was resuspended at a concentration of 10 mg ml−1 in endotoxin-free water and treated with DNase (Qiagen, Venlo, Limburg) at 100 μg ml−1 and RNase A (Qiagen, Venlo, Limburg) at 25 μg ml−1 and incubated at 37°C for 1 h in a water bath. Proteinase K (Qiagen, Venlo, Limburg) was added to a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1 and incubated for 1 h in a 37°C water bath (Fischer, Koch and Haas 1983). The solution was then extracted with an equal volume of water-saturated phenol. The aqueous phase was collected and dialyzed against Milli-Q purified water and freeze-dried as above. The LPS was further purified by the addition of chloroform/methanol 2:1 [vol:vol] to remove membrane phospholipids (Folch, Lees and Sloane Stanley 1957) and further purified by an additional water-saturated phenol extraction and 75% ethanol precipitation to remove contaminating lipoproteins (Hirschfeld et al. 2000). For mass spectrometry (MS) structural analysis, 1 mg of purified LPS was converted to lipid A by mild-acid hydrolysis with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) at pH 4.5 as described previously (Caroff, Tacken and Szabo 1988).

Small-scale lipid A isolation from whole cells

Lipid A was prepared using an ammonium hydroxide/isobutyric acid-based extraction procedure (El Hamidi et al. 2005). Approximately 10 mg of lyophilized material derived from an overnight culture was resuspended in 400 μl of isobutyric acid and 1 M ammonium hydroxide 5:3 [vol/vol] and incubated at 100°C for 1 h. After cooling, individual samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 2000 × g, and supernatants were collected and diluted 1:1 [vol/vol] with endotoxin-free water. The samples were subsequently frozen and lyophilized overnight. The resultant material was then washed twice with 1 ml of methanol, and the insoluble lipid A was extracted in 200 μl of a mixture of chloroform, methanol and water 3:1:0.25 [vol/vol/vol]. One microliter of this extract was then spotted onto a MALDI target plate followed by 1 μl of 20 mg ml−1 norharmane matrix (chloroform:methanol 1:1 [vol/vol] (Sigma, St Louis, MO).

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight MS

Lipid A isolated by small-scale lipid A isolation procedures was analyzed on a AutoFlex Speed matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). Data were acquired in reflectron negative and positive modes with a Smartbeam laser with 1 kHz repetition rate and up to 500 shots were accumulated for each spectrum. Instrument calibration and all other tuning parameters were optimized using Agilent Tuning mix (Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA). Data were acquired and processed using flexControl and flexAnalysis version 3.3 (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA).

Structural analysis by electrospray ionization linear ion trap Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance MS

Lipid A was analyzed by electrospray ionization (ESI) in the negative ion mode on a linear ion trap Fourier transform (LTQ-FT) ion cyclotron resonance (ICR) mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). Samples were diluted to 1.0 mg ml−1 in chloroform/methanol 1:1 [vol/vol] and infused at a rate of 1.0 μl min−1 via a fused silica capillary (75 μm i.d./360 μm (o.d.) with a 30-μm spray tip (New Objective, Woburn, MA). Instrument calibration and tuning parameters were optimized using a solution of Ultramark 1621 (Lancaster Pharmaceuticals, PA) in both positive and negative ion modes. For experiments acquired in the ICR cell, the mass resolving power was set to 100 000 and ion populations were held constant by automatic gain control at 1.0 × 106 for mass spectra (MS) acquisition and at 5.0 × 105 for tandem mass spectra (MSn), respectively. For tandem mass spectra, the precursor ion selection window was set to 4 Da and the collision energy was set to 30% on the instrument scale. The collision-induced dissociation MSn analyses in the linear ion trap were acquired with an ion population of 1.0 × 104 and maximum fill time of 200 ms. The subsequent MS2, MS3 and MS4 events had an isolation window of 2 Da with a collision energy of 25%. All spectra were acquired over a time period of 1 min and averaged. Typically, MS and MS2 events were analyzed in the ICR cell and MS3 and MS4 events were analyzed in the LTQ. Data were acquired and processed using Xcalibur, Version 1.4 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) utilizing seven-point Gaussian smoothing.

Gas chromatography fatty acid analysis

LPS fatty acids were converted to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) and analyzed by gas chromatography (GC) as previously described (Somerville et al. 1996). Briefly, 10 mg of lyophilized bacterial cell pellet was incubated at 70°C for 1 h in 500 μl of 90% phenol and 500 μl of water. Samples were then cooled on ice for 5 min and centrifuged at 9391 × g for 10 min. The aqueous layer was collected and 500 μl of water was added to the lower (organic) layer and incubated again. This process was repeated two additional times and all aqueous layers were pooled together. Two milliliters of ethyl ether was added to the harvested aqueous layers, this mixture was then vortexed and centrifuged at 2095 × g for 5 min. The lower (organic) phase was then collected and 2 ml of ether was added back to the remaining aqueous phase. This process was carried out two additional times and the collected organic layer was then frozen and lyophilized overnight. LPS fatty acids were converted to fatty methyl esters, in the presence of 10 μg pentadecanoic acid (Sigma, St Louis, MO) as an internal standard, with 2 M methanolic HCl (Alltech, Lexington, KY) at 90ºC for 18 h. Converted fatty methyl esters were then extracted twice with hexane and run on a HP 5890 Series 2 Gas Chromatograph. Retention times were correlated to fatty acids using GC-FAME standards (Matreya, Pleasant Gap, PA).

Determination of cell membrane permeability

Membrane permeability was determined using an ethidium bromide (EtBr) uptake assay as previously described (Li and Nikaido 2004; Li, Zhang and Nikaido 2004; Murata et al. 2007). Cultures were inoculated 1:100 from overnight cultures in fresh media and grown for 5 h at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged at 4000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 1 ml PBS. Suspensions were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1 in PBS and incubated with 2.5 μM EtBr. To assess efflux pump activity, the efflux pump inhibitor, chlorpromazine hydrochloride (20 μg ml−1), was added to all adjusted suspensions. Uptake was assayed using excitation and emission of 515 and 600 nm, respectively, using a DTX-880 Multimode Plate Reader (Beckman Coulter, IN, Indiana).

Antibiotic resistance and minimum inhibitory concentration determination

Resistance to polymyxin B and polymyxin E (Colistin) was determined using E-test strips following the manufacturer's recommendation (E-test Solna, Sweden). Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) by broth microdilution was determined as previously described (Wiegand, Hilpert and Hancock 2008). Briefly, individual colonies were suspended in Mueller Hinton broth to OD600 0.136 (0.5 McFarland standard) and 50 μl was added to rows 1–11 of a 96-well plate. Fifty microliters of each antibiotic (2-fold dilutions—128–0 μg ml−1 final concentration unless otherwise stated) for carbenicillin ticarcillin, piperacillin, cefoperazone chloramphenicol, minocycline, rifampicin and ciprofloxacin (2-fold dilutions—3–0 μg ml−1 final concentrations) were added to each row, columns 1–11 in one 96-well plate per antibiotic. Fifty microliters of a 1:100 dilution at an OD600 0.14 inoculum was added to columns 1–11. Column 11 was used as a growth control and column 12 was a media-only control. Plates were allowed to grow for 16–20 h at 37°C. Inhibition was determined by visual inspection.

RESULTS

Structural identification of PA lipid A acylation using MS

The PA lipid A structure has been proposed with alternating 3-hydroxylaurate (3-OH C12) and 3-hydroxydecanoate (3-OH C10) fatty acids attached to the glucosamine backbone with secondary 2-hydroxylaurate and laurate fatty acids attached to the 2 and 2′ positions. Initially, we sought to characterize PA lipid A to define the specific position of the laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate fatty acids. Lipid A extracted from the WT PAK, a laboratory-adapted strain of PA was analyzed via ESI LTQ-FT MS (Fig. S1, Supporting Information). All relevant anions were assigned a lipid A structure based on accurate mass of the precursor ion and tandem MS (Table S1 and Fig. S2, Supporting Information). The base peak at m/z 1446 corresponded to diphosphoryl penta-acylated lipid A with three primary fatty acids and two secondary fatty acids (Fig. S2, Supporting Information) and was consistent with previous reports (Ernst et al. 2006). Further details on the tandem MS experiments with explanation of acyl chain localization were included in the SI. The primary acyl chains consisted of two amide linked 3-hydroxylaurate fatty acids at the C-2 and C-2′ positions and one ester-linked 3-hydroxydecanoate at the C-3′ position. Secondary fatty acids also known as acyl-oxo-acyl fatty acids were confirmed at the C-2 and C-2′ positions. Evaluation of the lipid A fragmentation patterns placed the laurate at the C-2′ position and the 2-hydroxylaurate at the C-2 position (Fig. S2, Supporting Information). Note, the aforementioned tandem MS experiments did not determine the position of the hydroxyl group for the 2-hydroxylaurate acyl chain. The hydroxyl specification was based on the literature and gas chromatography–flame ionization detection (GC-FID) data (vide infra). There was no indication of these fatty acids in the converse configuration indicating that these additions were specific to each position.

Identification and role of PA0011 and PA1343 as potential lauryl transferase enzymes

After identifying the positioning of lipid A laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate, we identified the lauryl transferase enzymes mediating this addition in PA. Homologs of the E. coli HtrB enzyme were identified utilizing the known amino acid sequence of the E. coli HtrB enzyme (GenBank Accession #P0ACV0). Two PA genes, PA0011 (termed htrB1) and PA3242 (termed htrB2), were identified. PA3242 showed the highest percent identity to E. coli htrB at 47%, while PA0011 showed 30% identity.

Identification of two candidate htrB genes in PA suggested that more than one enzyme was responsible for the addition of C12 fatty acyls to PA lipid A. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed on lipid A extracted from mutants lacking either PA0011 and PA3242 to identify their contribution in secondary lipid A modification.

Lipid A was isolated from the ΔhtrB1 and ΔhtrB2 mutants, as well as the WT and screened by MALDI-TOF MS in the negative ion mode. Loss of 2-hydroxylaurate or laurate from the major WT ion m/z 1446 (Fig. 2A) indicated the loss of a specific acyl transferase activity. The ΔhtrB1 mutant displayed a major ion of m/z 1248 (Fig. 2B), corresponding to the mass loss of a 2-hydroxylaurate fatty acid (Δm/z 198) from the WT. Conversely, the ΔhtrB2 mutant displayed the major ion at m/z 1264 (Fig. 2C), demonstrating the loss of a laurate fatty acid (Δ m/z 182) from the WT. Complementation of the mutant strains with the appropriate gene restored WT lipid A structure (Fig. S5, Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

MALDI-TOF MS of (A) WT major ion peak m/z 1446.8; (B) ΔhtrB1 major peak m/z 1248 corresponding to a loss of 2-hydroxylaurate at the C-2 position; (C) ΔhtrB2 major peak at m/z 1264 resulting from a loss of laurate at the C-2’ position.

The lipid A structures for the ΔhtrB1 and ΔhtrB2 mutants were determined via tandem MS (Figs S3 and S4, Supporting Information). Refer to SI for further details on confirmation of the lipid A structures. The base peak (m/z 1248) in the ΔhtrB1 mutant spectrum (Fig. 2B) was determined to be diphosphoryl tetraacylated lipid A containing primary amide-linked 3-hydroxylaurate fatty acyls at the C-2 and C-2′ positions, primary ester-linked 3-hydroxydecanoate at the C-3′ position and a secondary laurate acyl chain at the C-2′ position. The base peak (m/z 1264) in the ΔhtrB2 mutant spectrum (Fig. 2C) was determined to be diphosphoryl tetraacylated lipid A with the following configuration: primary amide-linked 3-hydroxylaurate fatty acyls at the C-2 and C-2′ positions, primary ester-linked 3-hydroxydecanoate at the C-3′ position and a secondary 2-hydroxylaurate acyl chain at the C-2 position. Note, tandem MS did not determined the position of the hydroxyl group on the C12(2-OH) acyl chain. Refer to GC-FID data (vide infra).

Analysis of fatty acids by GC-FID

Results from MALDI-TOF MS analysis showing specificity of HtrB1 for the addition of 2-hydroxylaurate and HtrB2 for laurate addition were confirmed by GC analysis. Fatty acid peaks were assigned based on known FAME standards. The amount of each lipid A specific fatty acid was calculated in reference to a pentadecanoic acid internal standard and expressed as a percentage of total fatty acids. The ΔhtrB1 mutant showed a decrease in 2-hydroxylaurate as compared to the WT strain, while maintaining equivalent levels of C12. Conversely, the ΔhtrB2 mutant had equivalent levels of 2-hydroxylaurate as the WT, but was almost devoid of laurate (Fig. 3). Taken together, these data confirm that HtrB1 is responsible for the addition of 2-hydroxylaurate, while HtrB2 adds laurate.

Figure 3.

GC analysis of lipid A isolated from WT (white bars), ΔhtrB1 (gray bars) and ΔhtrB2 (black bars). A loss of C12 was seen in ΔhtrB2 while the levels of 2OH-C12 were diminished in the ΔhtrB1 mutant.

Deletion of PA htrB genes alters growth

As previously shown, deletion of the htrB gene in E. coli inhibited growth in rich media at temperatures above 33°C due to defects in membrane remodeling and stability. To assess if deletion of the PA htrB genes displayed similar growth defects at elevated temperatures, the individual mutant strains were grown in rich media over a wide range of temperatures, 25, 37 and 42°C (Fig. 4). The ΔhtrB1 mutant showed similar growth characteristics as compared to WT at all growth temperatures. The ΔhtrB2 mutant only showed a major growth defect at 25ºC and minor defects at 37 and 42ºC. Growth of the ΔhtrB2 mutant was restored after cultures initially grown at the non-permissive temperature (25°C) were transferred to the permissive temperature (37°C) (data not shown). These data suggest that these enzymes are non-redundant, since growth at low temperatures was not sustainable with only HtrB1 function. The ability of the ΔhtrB1 mutant to grow comparable to the WT also indicates the importance of the secondary 2’ position fatty acid in proper membrane function.

Figure 4.

Growth curves of (A) WT (solid line), (B) ΔhtrB1 (dashed line), and (C) ΔhtrB2 (dotted line) at 25, 37 and 42°C. Curves are shown as the average of three biological replicates.

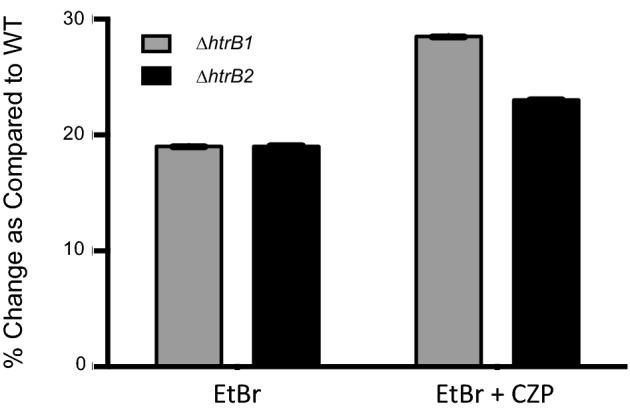

Altered membrane permeability in htrB mutants

Defective lipid A synthesis can alter membrane permeability leading to a decrease in cellular fitness. To measure membrane permeability changes in our mutants, we used an ethidium bromide (EtBr) uptake assay. EtBr passively enters bacterial cells and will intercalate with DNA and fluoresce under ultraviolet light. EtBr exits the cell by passive diffusion across the membrane and/or active transport through efflux pumps. To assess the passive diffusion of EtBr across the membrane as a measure of membrane permeability, efflux pump activity was inhibited by chlorpromazine hydrochloride (CZP, 20 μg ml−1). Both passive diffusion and active efflux were measured in the absence of CZP. Consistent with data from other bacterial systems, the loss of acyl chains on lipid A lead to increased membrane permeability in both ΔhtrB mutants. They showed a 19% increase in EtBr retention as a measure of active efflux and passive permeability over WT laboratory-adapted strain, PAK (Fig. 5). Cells incubated with EtBr in the presence of CZP exhibited an additional increase in fluorescence due to the expected increase in dye retention The CZP-treated ΔhtrB1mutant demonstrated a 29% increase, while the ΔhtrB2 mutant demonstrated a 23% increase in retained EtBr fluorescence when compared to WT (Fig. 5). The increased retention of EtBr in the CZP-treated ΔhtrB1 mutant suggests that the increased retention of EtBr in this mutant is not due to pump inactivation, but increased membrane permeability. The ΔhtrB2 mutant showed little difference in fluorescence between CZP-treated and -untreated cells. This could be due to either decreased or defective efflux pump activity, or the failure to be incorporated into the membrane of the ΔhtrB2 mutant, This result suggests that lipid A modifications can effect membrane protein function and/or composition in addition to membrane permeability.

Figure 5.

Ethidium bromide uptake assay measuring the permeability of ΔhtrB1 (gray bars) and ΔhtrB2 (black bars) cell membranes. Passive permeability with active efflux pump activity was measured by EtBr alone. EtBr plus the efflux pump inhibitor CZP measured passive permeability alone.

Resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides

Altered membrane permeability can result in increased sensitivity to antimicrobial peptides; therefore, we assayed the WT, ΔhtrB1 and ΔhtrB2 strains for their ability to resist killing by the cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) polymyxin B and polymyxin E (colistin). The polymyxins are positively charged cyclic peptides with hydrophobic tails (Bergen et al. 2012), thus allowing the molecule to bind to outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria through electrostatic interactions and traverse the membrane through the formation of pores.

After exposure to either polymyxin B or colistin, WT showed a zone of inhibition (no growth) at 3.0 μg ml−1. As would be expected with the increased permeability, the ΔhtrB2 mutant showed increased susceptibility to both polymyxin B (2 μg ml−1) and colistin (1.5 μg ml−1). These values place the mutant in the susceptible range, as outlined in the M100–23 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twenty-Third Informational Supplement. The ΔhtrB1 mutant did show increased membrane permeability; however, no change was observed in its susceptibility to polymyxin B (3 μg ml−1). Furthermore, a slight increase in resistance to colistin (4 μg ml−1) was observed; this value is considered in the intermediate range as outlined in the M100–23 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of WT, ΔhtrB1 and ΔhtrB2 by polymyxin B (black bars) and colistin (gray bars). Each experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Resistance to antibiotics

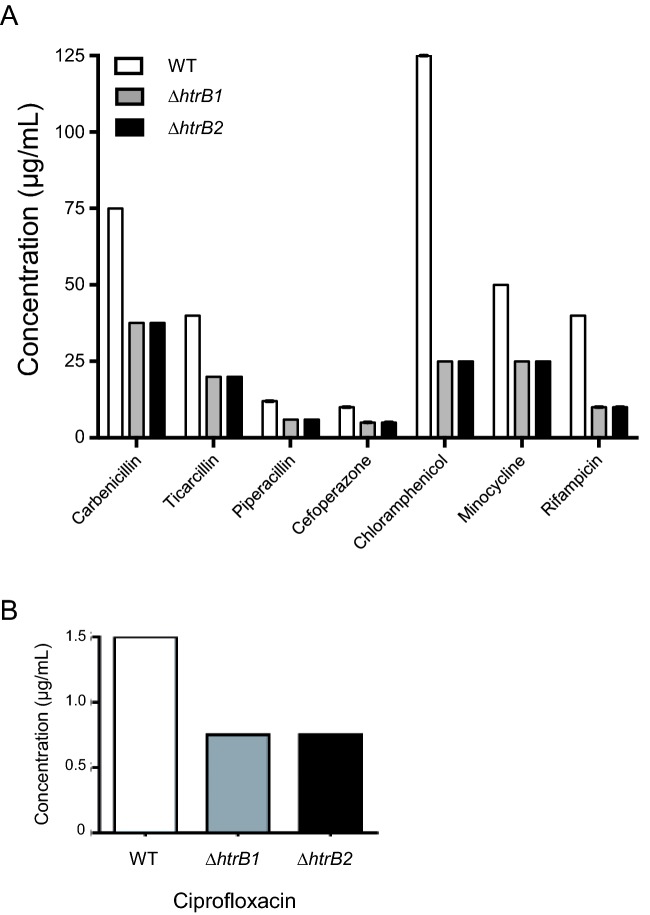

As CAMPs only represent a small subset of available antibiotic treatments, both mutants were screened for changes in susceptibility to 25 antibiotics of different classes by disc diffusion assay (data not shown). Antibiotic classes included cell wall inhibitors, ribosome inhibitors and DNA replication inhibitors. Initial screening resulted in the identification of eight antibiotics with altered susceptibility. These antibiotics were the cell wall inhibitors carbenicillin, ticarcillin, piperacillin and cefoperazone, protein synthesis inhibitors chloramphenicol and minocycline, the DNA synthesis inhibitor ciprofloxacin and the RNA polymerase inhibitor rifampicin. The other 17 antibiotics tested showed no change as compared to WT profiles and were excluded from further analysis. The eight antibiotics identified by disc diffusion assay were subsequently tested in MIC assays (Wiegand, Hilpert and Hancock 2008). Carbenicillin, ticarcillin, piperacillin, cefoperazone, minocycline and ciprofloxacin all showed a 2-fold decrease in MIC over WT for both mutants. whereas the mutant strains showed a 4- and 3-fold decrease in MIC, as compared to WT for chloramphenicol and rifampicin, respectively (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Antibiotic susceptibility of WT (white bars), ΔhtrB1 (gray bars) and ΔhtrB2 (black bars) measured by an MIC assay in Mueller Hinton broth. Antibiotics tested included cell wall synthesis inhibitors (carbenicillin, ticarcillin, piperacillin and cefoperazone), protein synthesis inhibitors (chloramphenicol and minocycline), RNA polymerase inhibitor (Rifampicin) and DNA gyrase inhibitor (ciprofloxacin).

CONCLUSIONS

A comprehensive understanding of lipid A biosynthesis and modification is an important component for elucidating how pathogens adapt to their environments. Basic synthesis of PA lipid A and the later modifications, such as addition of palmitate, deacylation of fatty acid moieties and additions to the terminal phosphate groups have been characterized and continue to be areas of study (Moskowitz et al. 2004; Ernst et al. 2006; Reynolds et al. 2006; Nowicki et al. 2014; Thaipisuttikul et al. 2014). Our current work focused on determining the structure of PA lipid A with regard to the position of laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate additions, as well as investigating the roles these secondary additions make to bacterial growth. Although the base structure for PA lipid A had been suggested, the exact location of the laurate and 2-hydroxylaurate had not been definitively assigned. The work presented here verified the PA structure as having an ester-linked 2-hydroxylaurate fatty acid at the C-2 position and an ester-linked laurate at the C-2′ position.

Once the structure had been determined, we sought to identify the enzymes responsible for these modifications and the role these lipid A structures play in bacterial fitness and membrane function. Laurate addition in other Gram-negative bacteria is mediated by the HtrB (LpxL) enzyme. Investigation into possible HtrB homologs using the known amino-acid sequence from E. coli identified two possible lipid A modification enzymes encoded by PA0011 (hrtB1) and PA3242 (htrB2). Clean deletions of each gene were generated and subjected to analysis by MS and GC to evaluate which, if any, of these genes encoded a functional HtrB enzyme. Results showed that both of the identified genes in PA encode an HtrB enzyme. Each enzyme was able to modify lipid A by addition of an acyl-oxy-acyl fatty acid to the base lipid A structure in a site-specific manner. GC and MS collectively showed that PA0011 (HtrB1) exclusively mediates the addition of the C-2 position 2-hydroxylaurate, while PA3242 (HtrB2) adds the C-2’ position laurate.

The differences seen in the site of addition between the HtrB1 and HtrB2 were reflected in the functional assays performed. One of the early effects of mutating the htrB gene in E. coli was drastically altered growth. A non-permissive growth temperature phenotype for the E. coli mutant (>33°C) resulted in the designation, high-temperature-regulated gene B (htrB). Elevated temperature growth was unaffected for each PA mutant suggesting that a single PA HtrB enzyme was sufficient to maintain a normal growth phenotype; however, defects in growth were observed for the ΔhtrB2 mutant strain at low temperatures. Preliminary data indicate that PA increases the amount of 2-hydroxylaurate fatty acids incorporated into lipid A at lower temperatures. The enzyme responsible for this modification is LpxO. Interestingly, in PA PAO-1 genome, two potential homologous have been annotated. This increase in hydroxylation may allow for necessary alterations in membrane fluidity as growth temperatures are reduced. Additionally, there may be a further delay in lipid A trafficking due to suboptimal MsbA binding, the inner membrane lipid A transporter that does not support normal bacterial growth (Zhou et al. 1998). Although the low temperature growth defect in the ΔhtrB2 was surprising, the growth phenotype of the ΔhtrB1 mutant showing no change from WT was not. Multiple laboratory-adapted, environmental and clinical isolates of PA produce a lipid A species devoid of the acyl-oxo-acyl 2-hydroxylaurate addition at the C-2 position (Ernst et al. 2003). The variation in C-2 position addition may be important for adaptations to currently unidentified membrane stress conditions.

Defects in lipid A biosynthesis have resulted in membrane permeability alterations resulting in increased sensitivity of bacterial cells to environmental changes and/or assaults leading to cell damage and possibly death. HtrB mutants were assayed for permeability changes using ethidium bromide accumulation. Both mutants had increased intercellular EtBr accumulation compared to WT. Passive and active passage of the EtBr molecule across the ΔhtrB2 mutant membrane showed an increase of 19 and 23% over WT, respectively. Permeability results for the ΔhtrB1 mutant assayed without efflux inhibition were identical to the ΔhtrB2 mutant; however, when the efflux pump inhibitor was added, these cells demonstrated an additional increase of 10% over WT. Overall, these results can be taken together to show that both mutants have significantly more permeability in their membranes over WT due to the lack of a fifth acyl chain.

Increased permeability results for both mutant strains should reasonably result in an increase in susceptibility to CAMPS, as these peptides electrostatically interact with LPS in the membrane. However, when assayed for the ability to resist killing by CAMPs, only ΔhtrB2 showed increased sensitivity placing this mutant in the susceptible range. The ΔhtrB1mutant showed a slight increase in resistance to colistin. While it was not a substantial change, it could indicate that the available hydroxyl group increases the interaction between colistin and the membrane thus aiding in membrane disruption.

While CAMP susceptibility was only slightly altered, antibiotic susceptibility to carbenicillin, ticarcillin, piperacillin, cefoperazone, chloramphenicol, minocycline, rifampicin and ciprofloxacin all increased in the both mutants by at least 2-fold. Similar results for ciprofloxacin and rifampicin have been seen in an LpxL knockout in E. coli indicating the importance for this modification in antibiotic resistance (Liu et al. 2010). The increased efficacy of these antibiotics can be attributed to the overall enhancement of cell permeability in both mutants leading to a surge in cellular drug uptake and retention. Lipid soluble antibiotics such as chloramphenicol, minocycline, rifampicin and ciprofloxacin can pass freely through lipid membranes. Increased membrane weakness and the resulting increase in cellular stress would enhance affectivity of sublethal doses of these antibiotics. Water-soluble drugs such as carbenicillin, ticarcillin, piperacillin and cefoperazone enter bacterial cells through pores or aqueous channels. The ethidium bromide accumulation assay indicated some alteration in efflux pumps in the mutant strains. Although the exact deficiency remains unknown, it can be hypothesized that the alteration in these pumps would increase the amount of drug retained in the cell.

The results of the studies presented in this work confirm a role for both HtrB enzymes in the maintenance of the composition of the outer membrane in PA, although the roles for the resulting lipid A structures are still not known. Increased permeability and susceptibility indicate both HtrBs as targets for traditional antimicrobial therapy. Additionally, the HtrB2 mutant demonstrated severe growth defects at low temperatures, which may be useful for pathogen eradication during environmental growth. Targeting PA on hospital surfaces and equipment would greatly reduce the incidence of infection and circumvent a need for new infection treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Francesca Gardner and Kelsey Gregg for their editorial assistance. These studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01AI047938 (RKE). The MS experiments conducted by JWJ were performed at the University of Washington's Proteomics Resource, Seattle, Washington (UWPR95794). Additional support was provided by the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy Mass Spectrometry Center (SOP1841-IQB2014).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Conflict of interest. None declared.

REFERENCES

- Bergen PJ, Landersdorfer CB, Zhang J, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ‘old’ polymyxins: what is new? Diagn Micr Infec D. 2012;74:213–23. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozek KA, Raetz CR. Biosynthesis of lipid A in Escherichia coli. Acyl carrier protein-dependent incorporation of laurate and myristate. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:15410–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroff M, Tacken A, Szabo L. Detergent-accelerated hydrolysis of bacterial endotoxins and determination of the anomeric configuration of the glycosyl phosphate present in the ‘isolated lipid A’ fragment of the Bordetella pertussis endotoxin. Carbohyd Res. 1988;175:273–82. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(88)84149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Kumar A, Schweizer HP. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation. J Microbiol Meth. 2006;64:391–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementz T, Bednarski JJ, Raetz CR. Function of the htrB high temperature requirement gene of Escherichia coli in the acylation of lipid A: HtrB catalyzed incorporation of laurate. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12095–102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementz T, Zhou Z, Raetz CR. Function of the Escherichia coli msbB gene, a multicopy suppressor of htrB knockouts, in the acylation of lipid A. Acylation by MsbB follows laurate incorporation by HtrB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10353–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElHamidi A, Tirsoaga A, Novikov A, et al. Microextraction of bacterial lipid A: easy and rapid method for mass spectrometric characterization. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1773–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D500014-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst RK, Adams KN, Moskowitz SM, et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipid A deacylase: selection for expression and loss within the cystic fibrosis airway. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:191–201. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.191-201.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst RK, Hajjar AM, Tsai JH, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipid A diversity and its recognition by Toll-like receptor 4. J Endotoxin Res. 2003;9:395–400. doi: 10.1179/096805103225002764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Koch HU, Haas R. Improved preparation of lipoteichoic acids. Eur J Biochem/FEBS. 1983;133:523–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons HS, Lin S, Cotter RJ, et al. Oxygen requirement for the biosynthesis of the S-2-hydroxymyristate moiety in Salmonella typhimurium lipid A. Function of LpxO, A new Fe2+/alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase homologue. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32940–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, et al. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 2000;165:618–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karow M, Fayet O, Cegielska A, et al. Isolation and characterization of the Escherichia coli htrB gene, whose product is essential for bacterial viability above 33 degrees C in rich media. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:741–50. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.741-750.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karow M, Georgopoulos C. Sequencing, mutational analysis, and transcriptional regulation of the Escherichia coli htrB gene. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2285–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karow M, Georgopoulos C. Isolation and characterization of the Escherichia coli msbB gene, a multicopy suppressor of null mutations in the high-temperature requirement gene htrB. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:702–10. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.702-710.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NG, Sunshine MG, Engstrom JJ, et al. Mutation of the htrB locus of Haemophilus influenzae nontypable strain 2019 is associated with modifications of lipid A and phosphorylation of the lipo-oligosaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27151–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XZ, Nikaido H. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria. Drugs. 2004;64:159–204. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XZ, Zhang L, Nikaido H. Efflux pump-mediated intrinsic drug resistance in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrobial Agents Ch. 2004;48:2415–23. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2415-2423.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Tran L, Becket E, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity profiles determined with an Escherichia coli gene knockout collection: generating an antibiotic bar code. Antimicrob Agents Ch. 2010;54:1393–403. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00906-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur I, Jones JW, Goodlett DR, et al. Role of pagL and lpxO in Bordetella bronchiseptica lipid A biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4726–35. doi: 10.1128/JB.01502-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz SM, Ernst RK, Miller SI. PmrAB, a two-component regulatory system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa that modulates resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and addition of aminoarabinose to lipid A. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:575–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.2.575-579.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Tseng W, Guina T, et al. PhoPQ-mediated regulation produces a more robust permeability barrier in the outer membrane of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7213–22. doi: 10.1128/JB.00973-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki EM, O'Brien JP, Brodbelt JS, et al. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa LpxT reveals dual positional lipid A kinase activity and co-ordinated control of outer membrane modification. Mol Microbiol. 2014;94:728–41. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CM, Ribeiro AA, McGrath SC, et al. An outer membrane enzyme encoded by Salmonella typhimurium lpxR that removes the 3’-acyloxyacyl moiety of lipid A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21974–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603527200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville JE, Jr, Cassiano L, Bainbridge B, et al. A novel Escherichia coli lipid A mutant that produces an antiinflammatory lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:359–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI118423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swords WE, Chance DL, Cohn LA, et al. Acylation of the lipooligosaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae and colonization: an htrB mutation diminishes the colonization of human airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4661–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4661-4668.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaipisuttikul I, Hittle LE, Chandra R, et al. A divergent Pseudomonas aeruginosa palmitoyltransferase essential for cystic fibrosis-specific lipid A. Mol Microbiol. 2014;91:158–74. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal O, Jann K. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides: extraction with phenol–water and further applications of the procedure. In: Whistler RL, Wolfan ML, editors. Methods In Carbohydrate Chemistry. New York: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:163–75. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, White KA, Polissi A, et al. Function of Escherichia coli MsbA, an essential ABC family transporter, in lipid A and phospholipid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12466–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.