Abstract

The adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin (CyaA, ACT or AC-Hly) is a key virulence factor of the whooping cough agent Bordetella pertussis. CyaA targets myeloid phagocytes expressing the complement receptor 3 (CR3, known as αMβ2 integrin CD11b/CD18 or Mac-1) and translocates by a poorly understood mechanism directly across the cytoplasmic membrane into cell cytosol of phagocytes an adenylyl cyclase(AC) enzyme. This binds intracellular calmodulin and catalyzes unregulated conversion of cytosolic ATP into cAMP. Among other effects, this yields activation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1, BimEL accumulation and phagocyte apoptosis induction. In parallel, CyaA acts as a cytolysin that forms cation-selective pores in target membranes. Direct penetration of CyaA into the cytosol of professional antigen-presenting cells allows the use of an enzymatically inactive CyaA toxoid as a tool for delivery of passenger antigens into the cytosolic pathway of processing and MHC class I-restricted presentation, which can be exploited for induction of antigen-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte immune responses.

Keywords: adenylate cyclase toxin, membrane penetration, pore-formation, antigen delivery tool

This review covers recent advances in our understanding of mechanism of membrane penetration of Bordetella pertusis adenylate cyclase toxin.

Graphical Abstract Figure.

This review covers recent advances in our understanding of mechanism of membrane penetration of Bordetella pertusis adenylate cyclase toxin.

INTRODUCTION

Secreted bacterial protein toxins play a central role in modulation and subversion of host cell functions by pathogens. Therefore, analyzing molecular details of mechanisms of toxin action helps to unravel the mechanisms of cell function. Inactivated bacterial toxins are also useful as protective antigens for the treatment and prevention of bacterial infections. Quite a few pathogens secrete pore-forming proteins that penetrate and permeabilize host cell membranes. This brief review covers recent advances in our understanding of mechanism of membrane penetration of the adenylate cyclase toxin, an important virulence factor from the repeat in toxin (RTX) family of bacterial toxins.

CyaA ACTION ON TARGET MEMBRANE

RTX proteins exhibit a wide range of activities and molecular masses, ranging from 40 to over 600 kDa (Linhartova et al. 2010). A prominent group of RTX proteins consists of toxins that exhibit a cytotoxic pore-forming activity. This was first detected as a hemolytic halo surrounding colonies of uropathogenic Escherichia coli on blood agar plates (Goebel and Hedgpeth 1982). The RTX adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin (Fig. 1) is secreted by pathogenic Bordetellae via the type I secretion system (T1SS), formed by the CyaBDE proteins, using the same mechanism as HlyA, the RTX α-hemolysin of E. coli, which uses the HlyBD/TolC apparatus (Koronakis, Eswaran and Hughes 2004). By analogy, CyaB would operate as an ABC family transporter, recognizing the secretion signal of CyaA located within its last 74 residues (Sebo and Ladant 1993) and driving the insertion of an unfolded CyaA polypeptide into a tightly packed trimeric CyaBDE ‘channel-tunnel’ conduit, spanning across the entire cell wall. This enables CyaA excretion directly from bacterial cytoplasm into the external medium.

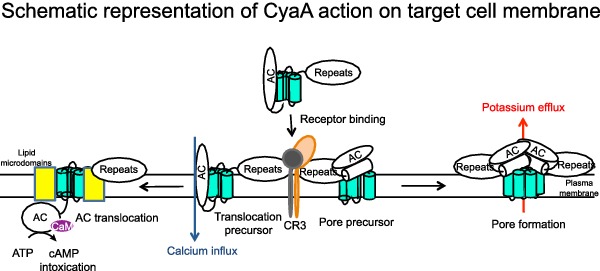

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the CyaA molecule. CyaA is a 1706 residue-long polypeptide that contains an N-terminal adenylate cyclase (AC) enzyme domain (∼400 residues) and a C-terminal pore-forming RTX hemolysin moiety of ∼1300 residues. The RTX hemolysin portion of CyaA itself consists of several functional subdomains. It contains (i) a hydrophobic pore-forming domain, comprising residues 500–700; (ii) an activation domain between residues 800 and 1000, where the posttranslational palmitoylation at two lysine residues (K860 and K983) occurs; (iii) a typical calcium-binding RTX domain, harboring the nonapeptide glycine- and aspartate-rich repeats, which form numerous (∼40) calcium-binding sites and the integrin-binding domain and (iv) the C-terminal secretion signal, respectively.

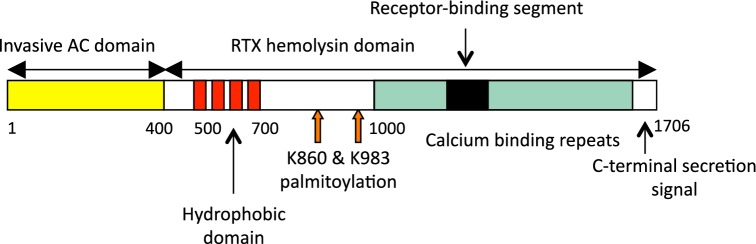

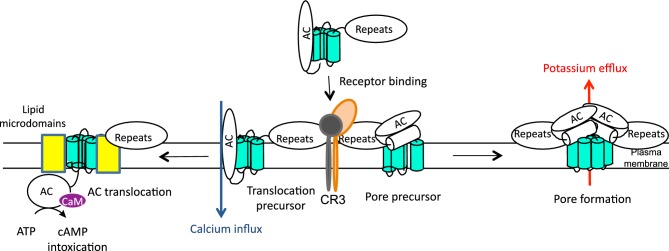

CyaA then acts as a swift multifunctional saboteur of host cell functions (Vojtova, Kamanova and Sebo 2006), perturbing physiology of various cell types by several mechanisms. Toxin binding to host cells is greatly enhanced by interaction with complement receptor 3 (Guermonprez et al. 2001), such as on the surface of host phagocytes. With about 50-fold lower efficacy (in terms of numbers of CyaA molecules bound per cell at a certain concentration), however, CyaA can bind and penetrate almost any host cell. This includes epithelial cells, most likely due to interaction with gangliosides clustered within lipid microdomains of cell membrane (Gordon et al. 1989). As schematically depicted in Fig. 2, upon penetration into cell membrane (bearing or not the CR3 receptor) the CyaA protein delivers its AC enzyme domain across the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells. In cell cytosol, the AC is activated by binding of cytosolic calmodulin and the AC domain catalyzes an extremely rapid (kcat∼2000 s−1) and uncontrolled conversion of intracellular ATP to cAMP. Accumulation of this key signaling molecule (second messenger) then subverts cellular physiology and rapidly suppresses bactericidal functions of phagocytes (Confer and Eaton 1982; Pearson et al. 1987; Kamanova et al. 2008; Cerny et al. 2015). At higher, but still physiologically relevant toxin concentrations (Eby et al. 2013), the CyaA-mediated cAMP signaling and ATP depletion, as well as pore-forming activity, can synergize in causing apoptosis or necrosis of phagocytes (Khelef and Guiso 1995; Bachelet et al. 2002; Basler et al. 2006; Hewlett, Donato and Gray 2006). Steep elevation of cAMP concentration by toxin action triggers and deregulates numerous signaling pathways downstream to protein kinase A (PKA) and Epac (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP). Recently, we could show that activation of PKA by toxin-produced cAMP translates, by an as-yet-uncharacterized signaling mechanism, into activation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. This controls numerous key mechanisms in leukocytes and among other blocks Toll-like receptor ligand-induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and bactericidal NO production in macrophages (Cerny et al. 2015). Moreover, SHP-1 activation yields stabilization of the proapoptotic BimEL protein, Bax activation and induction of macrophage apoptosis (Ahmad et al. 2015). In parallel, CyaA pores permeabilize the membrane of cells and promote potassium efflux from cells and possibly also sodium and water influx (Gray et al. 1998; Dunne et al. 2010; Fiser et al. 2012; Wald et al. 2014). This perturbs ion homeostasis and eventually provokes colloid-osmotic lysis of cells (Ehrmann et al. 1991). In contrast to some RTX toxins, which form large membrane pores allowing ATP leakage from cells, the cytolytic potency of the small CyaA pores does not appear to be potentiated by the mechanism involving ATP signaling-activated purinergic receptors (Skals et al. 2009; Munksgaard et al. 2012; Masin et al. 2013).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of CyaA action. CyaA targets primarily the host myeloid phagocytes that express the β2 integrin CD11b/CD18, known as complement receptor 3 (CR3) or Mac-1. The cell-invasive and pore-forming activities of CyaA appear to be independent and operating in parallel in target cell membrane. The current model predicts that two distinct CyaA conformers insert into target cell membrane. One would be the translocation precursor that would account for delivery of the AC domain across the lipid bilayer and provokes also a concomitant influx of calcium ions into cells. The other conformer would form a pore precursor that would oligomerize into CyaA pores, provoking potassium efflux from target cells. These two activities of a single polypeptide would then be to large extent mutually exclusive, being accomplished by the two conformer species forming in parallel and existing in an equilibrium that can be shifted in favor of prevalence of either of the conformers by alterations of CyaA acylation status, temperature, free calcium concentration, antibody binding or by specific residue substitutions (Rogel and Hanski 1992; Betsou, Sebo and Guiso 1993; Rose et al. 1995; Gray et al. 1998, 2001; Osickova et al. 1999, 2010; Rhodes et al. 2001; Basler et al. 2007).

RECEPTOR INTERACTION OF CyaA

CyaA uses the heterodimeric αMβ2 integrin as its receptor on myeloid phagocytes (Guermonprez et al. 2001). This explains why CD11b-expressing cells of the innate immune system, such as host neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), are most sensitive to ablation of their bactericidal functions by the cAMP-signaling action of CyaA, already at pM toxin concentrations.

The main segment involved in toxin binding to CD11b/CD18 was previously located between residues 1166 and 1281 of the calcium-binding and glycine-rich RTX repeat region of CyaA (El-Azami-El-Idrissi et al. 2003). We have recently shown that interaction of CyaA with CD11b/CD18 is initiated by recognition of the N-linked glycans of the CD11b subunit (Morova et al. 2008; Hasan et al. 2015). The high specificity of CyaA for binding of CD11b/CD18 and the very weak interaction of CyaA with the highly homologous CD11a/CD18 or CD11c/CD18 heterodimers appear to be determined by a specific binding site for CyaA present only in CD11b and not in the CD11a or CD11c subunits of the β2 integrin family. This CyaA-binding segment is located within residues 614–682 of CD11b, adjacent to its β-propeller domain (Osicka et al., submitted). Binding and penetration of CD11b-expressing cells by CyaA further depends on the loading of the RTX repeats of the hemolysin moiety by ∼ 40 calcium ions and on the covalent posttranslational palmitoylation of at least of one of the K860 and K983 residues, with the acylation of K983 being necessary and sufficient in supporting toxin action (Hackett et al. 1994; Masin et al. 2005).

PORE-FORMING ACTIVITY OF CyaA AND AC DOMAIN TRANSLOCATION

The RTX cytolysin (hemolysin) moiety of CyaA (∼1300 carboxy-proximal residues) is itself capable to form small cation-selective membrane pores of 0.6–0.8 nm in diameter (Benz et al. 1994). Properties of the CyaA pores, namely the pore lifetime and pore size, appear to depend on the applied membrane potential, but the presence of membrane potential is per se not an absolute prerequisite for formation of the CyaA pore (Knapp et al. 2008). The rate of formation as well as cation selectiveness and size of the CyaA pores all appear to be controlled by pairs of negatively charged glutamate residues (E509 + E516 and E570 + E581), located within the predicted amphipathic α-helical segments that are comprised between residues 500 and 700 of the hydrophobic domain of CyaA (Osickova et al. 1999; Basler et al. 2007). The hemolysin moiety further consists of an activation domain (residues 800–1000), where the covalent posttranslational palmitoylation of the ε-amino groups of internal lysine residues 860 and 983 of CyaA is accomplished by the coexpressed toxin acyltransferase CyaC (Hackett et al. 1994, 1995). A typical calcium-binding RTX domain between residues 1008 and 1590 then harbors the characteristic and more-or-less conserved nonapeptide RTX repeat motifs of a consensus sequence X-(L/I/F)-X-G-G-X-G-(N/D)-D. These form the numerous (∼40) calcium-binding sites of CyaA and are the hallmark of CyaA appurtenance to the RTX family (Rose et al. 1995). CyaA activity, indeed, strictly depends on physiological (>0.3 mM) concentrations of free calcium ions in order to fold into an active toxin capable to bind cells. Indeed, calcium ion loading induces major conformational changes of the CyaA molecule, triggering folding of the RTX domain and enabling CyaA to penetrate into cell membrane (Hanski and Farfel 1985; Hewlett et al. 1991; Knapp et al. 2003).

The sum of accumulated indirect evidence indicates that CyaA adopts two conformational states, yielding a translocation precursor and a pore-forming conformer precursor, respectively. These appear to be in equilibrium on or within target cell membrane and depending on the type of the CyaA conformer, two CyaA actions would follow. One would yield translocation of the AC-domain polypeptide across cellular membrane by the translocation precursor, and the other yielding formation of a cation-selective membrane pore. These two activities can be dissociated, and the balance between them shifted in either direction, by alterations of CyaA acylation status, temperature, free calcium concentration, antibody binding or by specific substitutions in the predicted amphipathic transmembrane segments of the pore-forming domain of CyaA, respectively (Rogel and Hanski 1992; Betsou, Sebo and Guiso 1993; Rose et al. 1995; Gray et al. 1998, 2001; Osickova et al. 1999, 2010; Rhodes et al. 2001; Basler et al. 2007).

The translocation across but not the mere insertion of CyaA into cytoplasmic membrane of cells appears to be driven by membrane potential (Otero et al. 1995; Veneziano et al. 2013). Toxin translocation across the lipid bilayer of cellular membrane is not preceded by toxin endocytosis (Gordon, Leppla and Hewlett 1988). CyaA translocation into cells proceeds directly across the target cytoplasmic membrane and exhibits a very short half-time of several dozens of seconds (Rogel and Hanski 1992). Moreover, this process does not depend on membrane permeabilization by CyaA pores (Osickova et al. 2010). The exact path of translocation of the ∼40 kDa AC domain polypeptide across the membrane lipid bilayer remains, however, poorly defined. A predicted alpha-helical segment linking the enzymatic and hydrophobic domains of CyaA has been proposed to be involved in the translocation of the AC domain across cellular membrane (Subrini et al. 2013). Indeed, AC translocation is abolished by the deletion of residues 375–485 of CyaA, or by binding of a monoclonal antibody that recognizes an epitope located between residues 373 and 399 of intact CyaA (Lee et al. 1999; Gray et al. 2001; Karst et al. 2012). Our recent unpublished results then show (Masin et al., manuscript in preparation) that negatively charged residues within this linker segment (residues 419–448) control the size and the frequency of formation of CyaA pores, while the positively charged residues of this segment appear to be involved in membrane destabilization and AC domain translocation across cellular membrane. We have recently shown that the membrane translocation intermediate of the AC polypeptide does itself participate in formation of a novel type of a transiently opened path across the cytoplasmic membrane that conducts extracellular calcium ions into the cytosol of monocytic cells (Fiser et al. 2007). Calcium infux then activates the protease calpain, which yields cleavage of talin that tethers CD11b/CD18 to actin cytoskeleton. This liberates the toxin-receptor complex for lateral relocation from the bulk phase of the membrane into the cholesterol-rich lipid microdomains, wherefrom the translocation of the AC domain into cell cytosol is completed (Bumba et al. 2010). Calpain can next process the AC domain, cleaving it off from the rest of the toxin molecule (Uribe et al. 2013). Our recent data further show that calcium influx mediated by the toxin translocation precursor, synergizing with potassium efflux through toxin pores, provokes a significant deceleration of the endocytic uptake of the toxin molecules from the cytoplasmic membrane. It appears that influx of calcium ions inhibits CyaA uptake by membrane recycling mechanisms and redirects membrane-associated CyaA into the slower clathrin-dependent endocytic uptake pathway (Fiser et al. 2012). As a result, a positive feedback loop is formed, as the more potassium leaks out from the cell, the slower is the clathrin-mediated uptake of CD11b/CD18/CyaA complexes in endocytic vesicles and the more exacerbated becomes the permeabilization of cells by toxin pores, thus further exacerbating the potassium efflux and cell permeabilization in a self-amplifying loop.

In parallel to the membrane-inserted CyaA translocation precursor-mediated calcium influx and translocation of the AC across cell membrane, the CyaA pore precursor causes permeabilization of cell membrane for monovalent cations (Osickova et al. 2010). This most likely occurs through association of CyaA monomers into transiently opened (flickering) oligomeric pores formed across cellular membrane, opening (associating?) and closing (dissociating?) with a half-time of ∼2 s (Vojtova-Vodolanova et al. 2009). Drop of cellular potassium levels, due to cell permeabilization by CyaA, then appears to activate a variety of cellular signaling cascades, as documented for the action of other pore-forming toxins (Bischofberger, Iacovache and van der Goot 2012). Indeed, Dunne et al. (2010) recently showed that the pore-forming activity of CyaA contributes to activation of the NALP3 inflammasome and induction of innate interleukin-1β responses through eliciting potassium efflux from CD11b-expressing cells exposed to CyaA. Our recent unpublished data then demonstrate that the pore-forming activity of CyaA is not required for mouse lung colonization by Bordetella pertussis in vivo and for the immunosuppressive action of the secreted CyaA on mouse DCs in vitro (Skopova et al., manuscript in preparation). The pore-forming capacity of CyaA, however, appears to be importantly contributing to exacerbation of infected lung inflammation, playing a role in virulence and lethality of B. pertussis infection in mice (Skopova et al., manuscript in preparation). Finally, further recent results show that the pore-forming activity of the genetically detoxified CyaA-AC− toxoid elicits Toll-like receptor and inflammasome signaling-independent maturation of CD11b-expressing DCs through potassium efflux-elicited activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (Svedova et al., submitted). This reveals a novel self-adjuvanting capacity of the CyaA-AC− toxoid. This property is then exploited in CyaA-based immunotherapeutic anti-cancer T-cell vaccines, which employ CyaA toxoids as a tool for delivery of heterologous cancer antigens into cytosol of antigen-presenting DCs for stimulation of tumor-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocyte responses (Linhartova et al. 2010; Sebo, Osicka and Masin 2014).

CONCLUSIONS

Research on mechanisms of CyaA action contributes to deepening of knowledge on molecular mechanisms of protein translocation across the lipid bilayer and on mechanisms of protein–protein interactions that precede protein oligomerization and pore formation. Further research on CyaA is then sorely needed also for gaining of a detailed understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the diagnostic and vaccine use of CyaA (Sebo, Osicka and Masin 2014). Enzymatically inactive CyaA-AC− toxoids have, indeed, been successfully used in T-cell recall response assays and in experimental CD8+ T-cell vaccines for tumor immunotherapy, building on the capacity of CyaA to deliver antigens into CD11b-expressing DCs for presentation to T cells (Sebo et al. 1995; Fayolle, Sebo and Ladant 1996; Saron et al. 1997; Fayolle et al. 1999, 2001; Osicka et al. 2000; Loucka et al. 2002; Mackova et al. 2006; Holubova et al. 2012; Sebo, Osicka and Masin 2014). CyaA toxoids have now been developed into a promising tool for parallel in vivo delivery of inserted CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell epitopes into both the MHC class I- and class II-dependent antigen presentation pathways of DCs. This enables in particular the induction of Th1-polarized and epitope-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses that are effective in experimental immunotherapy of HPV-induced tumors (www.genticel.com) (Preville et al. 2005; Mackova et al. 2006).

FUNDING

This work was supported by Grants No. P302/12/0460 (J.M.), GA15-09157S (R.O.), GA15-11851S (P.S.) and GA15-11851S (L.B.) from the Czech Science Foundation and by the Institutional Research Project RVO 61388971 of the Institute of Microbiology.

Conflict of interest. P.S., R.O. and J.M. are co-inventors on several patents protecting the use of CyaA as an antigen delivery tool and pertussis vaccine antigen. P.S. is co-owner of the Revabiotech SE working on novel pertussis vaccines.

REFERENCES

- Ahmad JN, Cerny O, Linhartova I, et al. cAMP signaling of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin through the SHP-1phosphatase activates the BimEL-Bax pro-apoptotic cascade in phagocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/cmi.12519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelet M, Richard MJ, Francois D, et al. Mitochondrial alterations precede Bordetella pertussis-induced apoptosis. FEMS Immunol Med Mic. 2002;32:125–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M, Knapp O, Masin J, et al. Segments crucial for membrane translocation and pore-forming activity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12419–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M, Masin J, Osicka R, et al. Pore-forming and enzymatic activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin synergize in promoting lysis of monocytes. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2207–14. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2207-2214.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz R, Maier E, Ladant D, et al. Adenylate cyclase toxin (CyaA) of Bordetella pertussis. Evidence for the formation of small ion-permeable channels and comparison with HlyA of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27231–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betsou F, Sebo P, Guiso N. CyaC-mediated activation is important not only for toxic but also for protective activities of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3583–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3583-3589.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger M, Iacovache I, van der Goot FG. Pathogenic pore-forming proteins: function and host response. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumba L, Masin J, Fiser R, et al. Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin mobilizes its beta2 integrin receptor into lipid rafts to accomplish translocation across target cell membrane in two steps. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000901. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny O, Kamanova J, Masin J, et al. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin blocks induction of bactericidal nitric oxide in macrophages through cAMP-dependent activation of the SHP-1 phosphatase. J Immunol. 2015;194:4901–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confer DL, Eaton JW. Phagocyte impotence caused by an invasive bacterial adenylate cyclase. Science. 1982;217:948–50. doi: 10.1126/science.6287574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne A, Ross PJ, Pospisilova E, et al. Inflammasome activation by adenylate cyclase toxin directs Th17 responses and protection against Bordetella pertussis. J Immunol. 2010;185:1711–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby JC, Gray MC, Warfel JM, et al. Quantification of the adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis in vitro and during respiratory infection. Infect Immun. 2013;81:1390–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00110-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrmann IE, Gray MC, Gordon VM, et al. Hemolytic activity of adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. FEBS Lett. 1991;278:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80088-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Azami-El-Idrissi M, Bauche C, Loucka J, et al. Interaction of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase with CD11b/CD18: role of toxin acylation and identification of the main integrin interaction domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38514–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle C, Ladant D, Karimova G, et al. Therapy of murine tumors with recombinant Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase carrying a cytotoxic T cell epitope. J Immunol. 1999;162:4157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle C, Osickova A, Osicka R, et al. Delivery of multiple epitopes by recombinant detoxified adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis induces protective antiviral immunity. J Virol. 2001;75:7330–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7330-7338.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle C, Sebo P, Ladant D, et al. In vivo induction of CTL responses by recombinant adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis carrying viral CD8+ T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1996;156:4697–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser R, Masin J, Basler M, et al. Third activity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase (AC) toxin-hemolysin. Membrane translocation of AC domain polypeptide promotes calcium influx into CD11b +monocytes independently of the catalytic and hemolytic activities. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2808–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser R, Masin J, Bumba L, et al. Calcium influx rescues adenylate cyclase-hemolysin from rapid cell membrane removal and enables phagocyte permeabilization by toxin pores. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002580. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel W, Hedgpeth J. Cloning and functional characterization of the plasmid-encoded hemolysin determinant of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:1290–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.3.1290-1298.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon VM, Leppla SH, Hewlett EL. Inhibitors of receptor-mediated endocytosis block the entry of Bacillus anthracis adenylate cyclase toxin but not that of Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1066–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1066-1069.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon VM, Young WW, Lechler SM, et al. Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bacillus anthracis and Bordetella pertussis. Different processes for interaction with and entry into target cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14792–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M, Szabo G, Otero AS, et al. Distinct mechanisms for K +efflux, intoxication, and hemolysis by Bordetella pertussis AC toxin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18260–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MC, Lee SJ, Gray LS, et al. Translocation-specific conformation of adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis inhibits toxin-mediated hemolysis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5904–10. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.5904-5910.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guermonprez P, Khelef N, Blouin E, et al. The adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis binds to target cells via the alpha(M)beta(2) integrin (CD11b/CD18) J Exp Med. 2001;193:1035–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett M, Guo L, Shabanowitz J, et al. Internal lysine palmitoylation in adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Science. 1994;266:433–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7939682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett M, Walker CB, Guo L, et al. Hemolytic, but not cell-invasive activity, of adenylate cyclase toxin is selectively affected by differential fatty-acylation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20250–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanski E, Farfel Z. Bordetella pertussis invasive adenylate cyclase. Partial resolution and properties of its cellular penetration. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5526–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan S, Osickova A, Bumba L, et al. Interaction of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin with complement receptor 3 involves multivalent glycan binding. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett EL, Donato GM, Gray MC. Macrophage cytotoxicity produced by adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis: more than just making cyclic AMP! Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:447–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett EL, Gray L, Allietta M, et al. Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Conformational change associated with toxin activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17503–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holubova J, Kamanova J, Jelinek J, et al. Delivery of large heterologous polypeptides across the cytoplasmic membrane of antigen-presenting cells by the Bordetella RTX hemolysin moiety lacking the adenylyl cyclase domain. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1181–92. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05711-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamanova J, Kofronova O, Masin J, et al. Adenylate cyclase toxin subverts phagocyte function by RhoA inhibition and unproductive ruffling. J Immunol. 2008;181:5587–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst JC, Barker R, Devi U, et al. Identification of a region that assists membrane insertion and translocation of the catalytic domain of Bordetella pertussis CyaA toxin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9200–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelef N, Guiso N. Induction of macrophage apoptosis by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase-hemolysin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp O, Maier E, Masin J, et al. Pore formation by the Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin in lipid bilayer membranes: role of voltage and pH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:260–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp O, Maier E, Polleichtner G, et al. Channel formation in model membranes by the adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis: effect of calcium. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8077–84. doi: 10.1021/bi034295f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koronakis V, Eswaran J, Hughes C. Structure and function of TolC: the bacterial exit duct for proteins and drugs. Ann Rev Biochem. 2004;73:467–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhartova I, Bumba L, Masin J, et al. RTX proteins: a highly diverse family secreted by a common mechanism. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:1076–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Gray MC, Guo L, et al. Epitope mapping monoclonal antibodies against Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2090–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2090-2095.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loucka J, Schlecht G, Vodolanova J, et al. Delivery of a MalE CD4(+)-T-cell epitope into the major histocompatibility complex class II antigen presentation pathway by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1002–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.2.1002-1005.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackova J, Stasikova J, Kutinova L, et al. Prime/boost immunotherapy of HPV16-induced tumors with E7 protein delivered by Bordetella adenylate cyclase and modified vaccinia virus Ankara. Cancer Immunol Immun. 2006;55:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0700-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masin J, Basler M, Knapp O, et al. Acylation of lysine 860 allows tight binding and cytotoxicity of Bordetella adenylate cyclase on CD11b-expressing cells. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12759–66. doi: 10.1021/bi050459b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masin J, Fiser R, Linhartova I, et al. Differences in purinergic amplification of osmotic cell lysis by the pore-forming RTX toxins Bordetella pertussis CyaA and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae ApxIA: the role of pore size. Infect Immun. 2013;81:4571–82. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00711-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masin J, Osickova A, Fiser R, et al. Dual function of a segment linking the adenylate cyclase enzyme and cytolysin moieties of Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin: Role of oppositely charged residues. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Morova J, Osicka R, Masin J, et al. RTX cytotoxins recognize β2 integrin receptors through N-linked oligosaccharides. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5355–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711400105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munksgaard PS, Vorup-Jensen T, Reinholdt J, et al. Leukotoxin from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans causes shrinkage and P2X receptor-dependent lysis of human erythrocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1904–20. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osicka R, Osickova A, Basar T, et al. Delivery of CD8(+) T-cell epitopes into major histocompatibility complex class I antigen presentation pathway by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase: delineation of cell invasive structures and permissive insertion sites. Infect Immun. 2000;68:247–56. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.247-256.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osicka R, Osickova A, Hasan S, et al. Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin is a unique ligand of the integrin complement receptor 3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10766. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osickova A, Masin J, Fayolle C, et al. Adenylate cyclase toxin translocates across target cell membrane without forming a pore. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:1550–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osickova A, Osicka R, Maier E, et al. An amphipathic alpha-helix including glutamates 509 and 516 is crucial for membrane translocation of adenylate cyclase toxin and modulates formation and cation selectivity of its membrane channels. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37644–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero AS, Yi XB, Gray MC, et al. Membrane depolarization prevents cell invasion by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9695–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RD, Symes P, Conboy M, et al. Inhibition of monocyte oxidative responses by Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. J Immunol. 1987;139:2749–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preville X, Ladant D, Timmerman B, et al. Eradication of established tumors by vaccination with recombinant Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase carrying the human papillomavirus 16 E7 oncoprotein. Cancer Res. 2005;65:641–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes CR, Gray MC, Watson JM, et al. Structural consequences of divalent metal binding by the adenylyl cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;395:169–76. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogel A, Hanski E. Distinct steps in the penetration of adenylate cyclase toxin of Bordetella pertussis into sheep erythrocytes. Translocation of the toxin across the membrane. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose T, Sebo P, Bellalou J, et al. Interaction of calcium with Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Characterization of multiple calcium-binding sites and calcium-induced conformational changes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26370–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saron MF, Fayolle C, Sebo P, et al. Anti-viral protection conferred by recombinant adenylate cyclase toxins from Bordetella pertussis carrying a CD8+ T cell epitope from lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3314–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebo P, Fayolle C, d'Andria O, et al. Cell-invasive activity of epitope-tagged adenylate cyclase of Bordetella pertussis allows in vitro presentation of a foreign epitope to CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3851–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3851-3857.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebo P, Ladant D. Repeat sequences in the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin can be recognized as alternative carboxy-proximal secretion signals by the Escherichia coli alpha-haemolysin translocator. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:999–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebo P, Osicka R, Masin J. Adenylate cyclase toxin-hemolysin relevance for pertussis vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13:1215–27. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.944900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skals M, Jorgensen NR, Leipziger J, et al. Alpha-hemolysin from Escherichia coli uses endogenous amplification through P2X receptor activation to induce hemolysis. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807044106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skopova K, Rossmann P, Kosova M, et al. Hemolytic activity of adenylate cyclase toxin is not required for colonization capacity but contributes to virulence of Bordetella pertussis. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Subrini O, Sotomayor-Perez AC, Hessel A, et al. Characterization of a membrane-active peptide from the Bordetella pertussis CyaA toxin. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:32585–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.508838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svedova M, Adkins I, Masin J, et al. Pore-forming activity of the adenylate cyclase toxoid activates dendritic cells to prime CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. doi: 10.1038/icb.2015.87. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe KB, Etxebarria A, Martin C, et al. Calpain-mediated processing of adenylate cyclase toxin generates a cytosolic soluble catalytically active N-terminal domain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneziano R, Rossi C, Chenal A, et al. Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin translocation across a tethered lipid bilayer. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20473–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312975110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtova J, Kamanova J, Sebo P. Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin: a swift saboteur of host defense. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtova-Vodolanova J, Basler M, Osicka R, et al. Oligomerization is involved in pore formation by Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. FASEB J. 2009;23:2831–43. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald T, Petry-Podgorska I, Fiser R, et al. Quantification of potassium levels in cells treated with Bordetella adenylate cyclase toxin. Anal Biochem. 2014;450:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]