Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

IgM+ FL B cells display a stronger BCR response than their GC B-cell counterpart despite significant BCR-related phosphatase activity.

M2 macrophages trigger DC-SIGN–dependent cell adhesion and BCR activation in IgM+ FL B cells with a highly mannosylated BCR.

Abstract

Follicular lymphoma (FL) results from the accumulation of malignant germinal center (GC) B cells leading to the development of an indolent and largely incurable disease. FL cells remain highly dependent on B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling and on a specific cell microenvironment, including T cells, macrophages, and stromal cells. Importantly, FL BCR is characterized by a selective pressure to retain surface immunoglobulin M (IgM) BCR despite an active class-switch recombination process, and by the introduction, in BCR variable regions, of N-glycosylation acceptor sites harboring unusual high-mannose oligosaccharides. However, the relevance of these 2 FL BCR features for lymphomagenesis remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that IgM+ FL B cells activated a stronger BCR signaling network than IgG+ FL B cells and normal GC B cells. BCR expression level and phosphatase activity could both contribute to such heterogeneity. Moreover, we underlined that a subset of IgM+ FL samples, displaying highly mannosylated BCR, efficiently bound dendritic cell–specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3–grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN), which could in turn trigger delayed but long-lasting BCR aggregation and activation. Interestingly, DC-SIGN was found within the FL cell niche in situ. Finally, M2 macrophages induced a DC-SIGN–dependent adhesion of highly mannosylated IgM+ FL B cells and triggered BCR-associated kinase activation. Interestingly, pharmacologic BCR inhibitors abolished such crosstalk between macrophages and FL B cells. Altogether, our data support an important role for DC-SIGN–expressing infiltrating cells in the biology of FL and suggest that they could represent interesting therapeutic targets.

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL), the most frequent indolent lymphoma, is characterized by the accumulation of clonal germinal center (GC) B cells retaining a strong dependence on their surrounding microenvironment for survival, growth, and drug resistance.1,2 Although the founder genetic hallmark of FL, the t(14;18) translocation, disrupts 1 immunoglobulin allele, expression of the surface B-cell receptor (BCR) is retained. In addition, whereas FL cells carry evidence of intraclonal evolution related to the ongoing somatic hypermutation process, mutational analysis of immunoglobulin variable regions reveals a counterselection of mutations affecting BCR structural integrity.3,4 Finally, resistance to anti-idiotype therapy was shown to rely on mutations of the targeted immunoglobulin sequence rather than on loss of BCR expression.5,6 Study of the FL BCR signaling profile highlighted a lack of constitutive activation together with a strong interindividual variability in both magnitude and kinetic of the signal.7,8 The reasons underlying such heterogeneity remain poorly understood. Phosphatase activity is high in FL B cells, and contributes to lowering the BCR signaling response. However, no comparison was performed with GC B cells, the normal counterpart of FL B cells, whereas mouse GC B cells have recently been demonstrated to exhibit high phosphatase activity and low BCR signaling.9,10 It remains thus unclear whether altered BCR signaling in malignant FL B cells is related to the lymphomagenesis process or to their specific cell of origin.

Two main hypotheses have been proposed regarding the source of BCR stimulation in FL. The first, detected in ∼20% of cases, is the self-reactivity of FL BCR, with vimentin recently identified as a shared autoantigen in FL.11,12 The second is related to the positive selection of N-glycosylation sites introduced by somatic hypermutations in the variable regions of immunoglobulin heavy and light chains (VH and VL) in >80% of FL patients, whereas they are rarely detected in normal B cells.13 Surprisingly, these added glycans, conversely to glycans of the Fc region of the same molecules, remain of immature type, leaving oligomannoses exposed in the antigen-binding site of FL surface immunoglobulin.14 BCR N-glycosylations were described as early genetic events in FL tumorigenesis15 and allow in vitro interaction with C-type lectins, including dendritic cell–specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3–grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN; CD209) and mannose receptor (MR; CD206).16 Recently, mannosylated V regions of FL BCR were reported to interact with opportunistic pathogen-derived lectins but were not sufficient to trigger functional interaction with human DC-SIGN.17 Only a subset of FL samples was able to bind to a mannose-specific bacterial lectin, suggesting an additional level of heterogeneity in FL BCR signaling. Collectively, these observations raise 2 questions: what are the mechanisms underlying the functional heterogeneity of FL BCR, and what are the endogenous ligands for FL BCR in vivo?

One of the most striking features of FL BCR is the selective pressure to retain surface immunoglobulin M (IgM) expression whereas the nonproductive allele undergoes normal class-switch recombination. Class-switch recombination blockade on the functional allele has been associated with recurrent mutations or deletions at the Sμ switch region.18,19 IgG+ tumors display a higher frequency of self-reactivity together with a higher number of somatic hypermutations whereas N-glycosylation sites were more commonly observed in IgM+ tumors.11 It is therefore tempting to speculate that the BCR isotype could influence BCR signaling and tumorigenesis pathways in FL but this hypothesis has never been tested. Concerning BCR ligands, both DC-SIGN and MR are expressed by various myeloid cell subsets.20,21 Interestingly, a high number of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have an adverse prognostic value in FL patients treated with conventional chemotherapy.22-24 Nevertheless, how TAMs could organize a functional synapse with FL B cells and what could be the role of lectin/BCR interaction in this crosstalk have not been considered.

The crucial role of BCR in FL pathogenesis together with the previously reported bad prognostic value of high FL TAMs prompted us to investigate whether FL TAMs expressed endogenous FL BCR ligands in situ, how such ligands could trigger BCR activation in malignant B cells, and what could be the role of the BCR isotype and glycosylation in this process. We demonstrated that IgM+, unlike IgG+, FL B cells were more responsive to BCR crosslinking than their normal GC B-cell counterpart and that phosphatase activity and BCR density were involved in this disparity. Moreover, DC-SIGN was present within the FL cell niche, could bind to highly mannosylated FL IgM BCR, and trigger their activation. Interestingly, both DC-SIGN blockade and therapeutic inhibitors of BCR signaling abrogated macrophage/B-cell crosstalk in patients displaying such high-mannose IgM BCR.

Patients, materials, and methods

Details are provided in the supplemental Methods available on the Blood Web site.

Cell samples

Subject recruitment followed institutional review board approval and the written informed consent process according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Tonsils were obtained from children undergoing routine tonsillectomy, lymph node biopsies from FL patients, and peripheral blood from adult healthy volunteers. Tonsil and FL B cells were purified using the B-cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec), and normal CD44−IgD− GC B cells were further sorted using a FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Peripheral blood monocytes were obtained using the CD14+ Microbeads kit (Miltenyi Biotec), and were cultured for 5 days with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor or macrophage colony-stimulating factor for M1 vs M2 commitment (50 ng/mL; R&D Systems), before the addition of lipopolysaccharide (100 ng/mL; Invivogen) and interferon-γ (20 ng/mL) vs interleukin-10 (IL-10) ± IL-4 (20 ng/mL; R&D Systems) for a 48-hour terminal differentiation.

Phosphoflow staining

Normal and malignant B cells were starved for 1 hour in RPMI1640–1% fetal calf serum before stimulation with anti-human IgM or IgG (10 µg/mL) in the presence or not of H2O2 (3.3 mM). The reaction was stopped by adding 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 80% methanol, rehydrated with phosphate-buffered saline–1% bovine serum albumin, and stained with anti-pSYK, anti-pBLNK, and anti-pERK1/2 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), as well as anti-κ (FL) or anti-CD38 (tonsils) antibodies (Abs). Phosphoprotein activation was quantified on CD38hiIgM+ and CD38hiIgG+ tonsil GC B cells, and on FL B cells expressing clonal heavy and light chains.

Immunofluorescence

Sorted GC B cells and purified FL B cells were stimulated with glass-coated anti-human IgM or anti-human IgG mAbs (10 μg/mL) before fixation, permeabilization, and staining for pCD79a, and IgM or IgG. They were also stimulated with 5 µg/mL recombinant human DC-SIGN chimeric molecule (rhDC-SIGN; R&D Systems) before fixation, permeabilization, and staining for DC-SIGN and IgM. When indicated, FL B cells were labeled with anti-human CD19 mAb before stimulation with anti-IgM or rhDC-SIGN. M1 and M2 macrophages were fixed and permeabilized before staining with SytoxBlue (Invitrogen), anti-human CD68, and anti-DC-SIGN.

All immunofluorescence experiments were analyzed with an SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems), and ImageJ software was used for image treatment.

Western blot experiments

rhDC-SIGN was conjugated to Dynabeads M-280 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Purified normal and malignant B cells were starved before stimulation by either anti-human IgM or rhDC-SIGN–coated beads and analysis of BCR-related protein phosphorylation.

Glycosylation of the μ chain was analyzed by digestion using endoglycosidase H (EndoH) and peptide:N-glycosidase F (PNGase; Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

B-cell coculture with macrophages

FL B cells were starved for 1 hour in the presence of Ibrutinib (1 µM), R406 (10 µM; Selleckchem), or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) before incubation with adherent M2 macrophages for 1 hour. B cells were removed and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer for western blot experiments.

Adherent M2 macrophages were incubated with neutralizing anti-DC-SIGN or anti-MR mAbs (350 ng/mL and 1 µg/mL, respectively) or corresponding mouse isotypic controls (BD Biosciences) for 4 hours. For adhesion experiments, coculture with FL B cells was initiated for 1 hour in RPMI1640–1% fetal calf serum before fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde and staining of macrophages with mouse IgG2b anti-DC-SIGN followed by A488-donkey anti-mouse IgG2b, and B cells with A549-goat anti-human IgM. For survival assay, FL B-cell viability was evaluated after 24 hours of coculture by staining of CD19+ B cells with Topro-3.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test or the unpaired parametric Student t test as appropriate. To compare DC-SIGN ratio of mean fluorescence intensity (rMFI) not normally distributed datasets, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn posttest for multiple testing corrections was used.

Results

FL B-cell response to BCR triggering

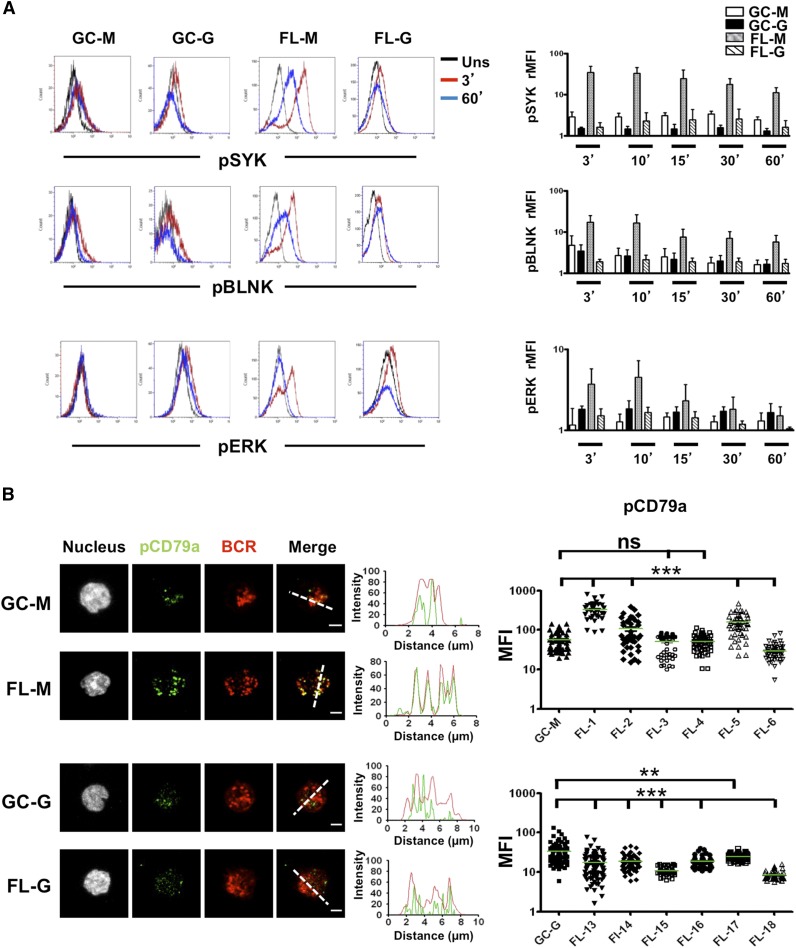

Because BCR signaling is dampened in mouse GC B cells due to phosphatase activity,9,10 we decided to reevaluate the strength of BCR signaling in FL B cells compared with their normal GC B-cell counterpart. Both IgM+ and IgG+ GC B cells demonstrated limited early and late response to BCR crosslinking in vitro (Figure 1A), whereas phosphatase inactivation by H2O2 restored phosphorylation of SYK, BLNK, and ERK in response to BCR triggering. These results indicated a reversible inhibition of BCR signaling in human GC B cells associated with phosphatase activity (supplemental Figure 1). Conversely, IgM+ FL B cells could be efficiently stimulated by IgM crosslinking in the absence of H2O2, as visualized by activation of BCR-dependent kinases by flow cytometry, and such activation was further increased in the presence of H2O2 (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1). In agreement, FL IgM BCR engagement induced a rapid phosphorylation of CD79a that colocalized with BCR aggregates (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 2). Strikingly, IgG+ FL B cells, unlike IgM+ FL B cells, did not exhibit an increased BCR response compared with normal GC B cells and immunofluorescence studies even revealed decreased signaling. However, the FL IgG BCR defect was reversed by stimulation with anti-BCR plus H2O2 (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

BCR activation in normal and malignant GC B cells. (A) B cells were purified from tonsils and FL samples and were stimulated with soluble goat anti-human IgM or IgG Abs for indicated time points. BCR activation was revealed using intracellular staining for pSYK, pBLNK, and pERK. GC B cells were gated based on CD38hi expression whereas IgM+ or IgG+ malignant FL B cells were further gated based on the expression of an appropriate tumor light chain (n = 5 for each subset). rMFI was obtained as the rMFI with/without BCR stimulation. Bars, mean ± SD. (B) GC B cells were sorted from purified tonsil B cells based on CD44−IgD− phenotype. Sorted GC B cells and purified FL B cells were stimulated for 10 minutes with coated mouse anti-human IgM or IgG mAbs before fixation, permeabilization, and staining with rabbit anti-pCD79a primary mAbs followed by A488-donkey anti-rabbit secondary Ab, and A549-goat anti-human IgM or A549-donkey anti-human IgG Abs. pCD79a MFI was obtained for 50 cells per sample (pool of 3 GC B-cell samples, 6 IgM FL samples, 6 IgG FL samples). Scale bar, 2.5 µm. **P < .01; ***P < .001; FL-G, IgG+ FL; FL-M, IgM+ FL; GC-G, IgM+ GC B cells; GC-M, IgM+ GC B cells; ns, not significant; Uns, unstimulated.

The discrepancy between the IgM+ and IgG+ FL B-cell response to BCR triggering was not explained by differences in the expression of classical BCR inhibitory molecules (supplemental Figure 3A). In particular, whereas FL B cells displayed reduced expression of the sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin-like lectin CD22 and the phosphatase SHP1 compared with normal centrocytes, such a decrease was similar for both IgM and IgG FL samples. In addition, expression of SHIP1, another crucial BCR-related phosphatase, was not modulated in malignant vs normal GC B cells. As previously reported,7 the density of BCR heavy chain was highly variable within FL samples without a significant correlation with their capacity to respond to BCR crosslinking. However, we pinpointed some differences between IgM and IgG FL B cells. In particular, IgG+ FL B cells, unlike IgM+ FL B cells, exhibited a decrease in their density of surface Ig compared with IgG+ memory and GC B cells (supplemental Figure 3B). In conclusion, IgG+ FL B cells, like normal GC B cells, failed to respond to BCR stimulation, a defect associated with a reduced BCR expression but that could be reversed by phosphatase inhibition. Conversely, IgM+ FL B cells retained some capacity to be activated by BCR crosslinking even if such a response was also restrained by phosphatase activity.

DC-SIGN expression within FL lymph nodes

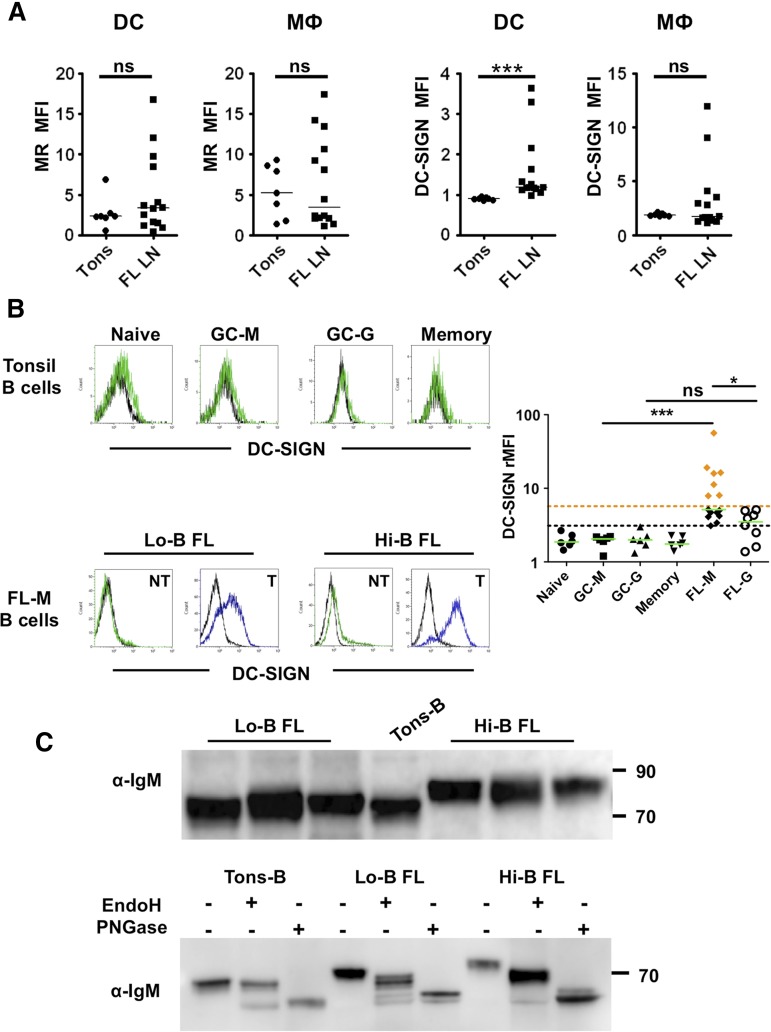

In the majority of FL cases, BCR stimulation is supposed to be antigen-independent but related to the interaction with C-type lectins. DC-SIGN/CD209 and MR/CD206 are the 2 lectins able to bind mannosylated FL BCR in vitro16 and have been described on dendritic cells and macrophages within normal lymphoid tissues.20,21 We decided to check for their expression within the FL cell niche. First, we highlighted, by flow cytometry,25 an overexpression of DC-SIGN on CD3/CD19/CD335−CD11c+ HLA-DR+CD14− classical dendritic cells in FL samples compared with reactive tonsils (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 4). DC-SIGN expression was also variably increased on CD3/CD19/CD335−CD11c+HLA-DR+CD14+ FL TAM. Conversely, both dendritic cells and macrophages expressed MR at a heterogeneous but similar level in tonsils and FL samples. We then decided to investigate DC-SIGN expression in situ. Interestingly, we could identify infiltrating CD68+DC-SIGN+ cells in contact with CD20+ FL cells in 2 distinct localizations: colonizing paracortical lymphatic sinuses and scattered in perifollicular areas (supplemental Figure 5). DCN46 anti-DC-SIGN antibody also strongly stained a network of CD68− cells expressing the Lyve-1 lymphatic endothelial cell marker.

Figure 2.

DC-SIGN binding by FL B cells. (A) Expression of MR and DC-SIGN on gated CD3/CD19/CD335−CD11c+HLA-DR+CD14− dendritic cells (DCs) and CD3/CD19/CD335−CD11c+HLA-DR+CD14+ macrophages (MΦ) in tonsils (n = 7) vs FL lymph nodes (FL LN) (n = 14). ***P < .001. (B) A488-conjugated rhDC-SIGN was used to stain normal tonsil B cell subsets (n = 6) and FL B cells (15 IgM+ and 8 IgG+ samples). CD38−CD10−IgM+ naive B cells (naive), CD38−CD10−IgM− memory B cells (memory), CD38hiCD10+IgM+ GC B cells (GC-M), and CD38hiCD10+IgM− GC B cells (GC-G) were compared. Within FL samples, tumoral B cells (T) and nontumoral B cells (NT) were segregated within CD20+ B cells through the expression of heavy and light chains. DC-SIGN binding was expressed as the rMFI obtained in the presence (green or blue line)/in the absence (black line) of Ca2+. IgM+ FL B cells with a DC-SIGN–binding capacity higher than IgG+ FL cells (Hi-B FL) were highlighted with orange diamonds; IgM+ FL B cells with a DC-SIGN–binding capacity similar to IgG+ FL cells (Lo-B FL) were highlighted with black diamonds. The black dotted line represents the maximum value of normal B cells; the orange dotted line, the maximum value of IgG+ FL B cells. *P < .05; ***P < .001. (C) Cell lysates from purified tonsil B cells and IgM+ FL B cells were immunoblotted with goat anti-human IgM Ab (top panel). When indicated, cell lysates were treated with EndoH or PNGase (bottom panel, shown is 1 representative experiment of 3).

IgM+ FL differentially bind DC-SIGN

To assess the capacity of FL B cells to bind DC-SIGN, we directly labeled the rhDC-SIGN chimeric molecule with Alexa Fluor 488 dye. Normal tonsil B cells, including naive, memory, and GC B cells of IgM and IgG phenotype, poorly bound A488-rhDC-SIGN. Conversely, we confirmed that DC-SIGN specifically bound malignant FL B cells, unlike nonmalignant residual B cells expressing the nontumor light-chain isotype, in the majority of IgM+ and IgG+ FL samples (n = 23; Figure 2B). However, the staining of IgM+ samples was very heterogeneous and significantly higher than that of IgG+ samples (median rMFI: 5.1 [3.1-56.5]; n = 15 vs 3.5 [1.4-5.1]; n = 8). In particular, we highlighted 2 groups of IgM+ FL samples, that is, DC-SIGN low-binding samples (Lo-B FL, median rMFI: 4.4 [3.1-5.1]; n = 8), displaying a similar staining intensity as IgG+ FL samples, and DC-SIGN high-binding samples (Hi-B FL, median rMFI: 16 [7.9-56.5]; n = 7).

We could not find a significant correlation between the fixation of rhDC-SIGN on IgM+ FL B cells and their amount of surface IgM or their capacity to respond to IgM crosslinking by phosphorylation of BCR-dependent kinases (supplemental Figure 6). Another potentially important parameter is the level and biochemical nature of added N-glycans. Sequence analysis of FL VH genes showed acquisition of at least 1 Asn-X-Ser/Thr N-glycosylation site in 2 of 3 IgG and 4 of 6 IgM (data not shown). However, this limited number of cases precluded any conclusion. Interestingly, the molecular size of heavy chain IgM from Hi-B FL was higher than that from Lo-B FL and normal tonsil IgM B cells, suggesting differences in glycosylation pattern (Figure 2C). We thus treated proteins extracted from purified B cells with 2 specific glycosidases, EndoH, which removes only mannosylated N-glycans, and PNGase, which cleaves all attached N-glycans, and revealed the size of μ chains. IgM from normal B cells were not affected by EndoH but were cleaved by PNGase, in agreement with a mature form of IgM. Conversely, the μ-chain band in FL patients was susceptible to EndoH that increased its mobility, with a greater effect in Hi-B FL than in Lo-B FL. Collectively, these data suggest a relationship between the capacity of FL B cells to bind DC-SIGN and the glycosylation profile of FL BCR.

DC-SIGN triggers strong BCR activation in Hi-B FL IgM+ FL samples

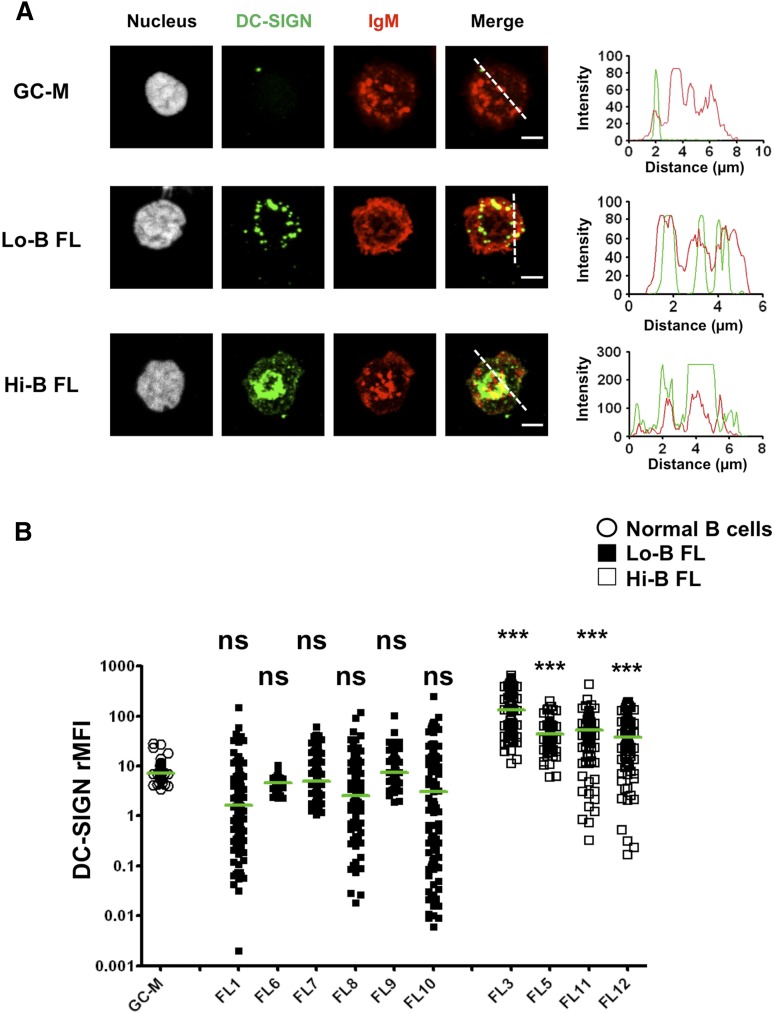

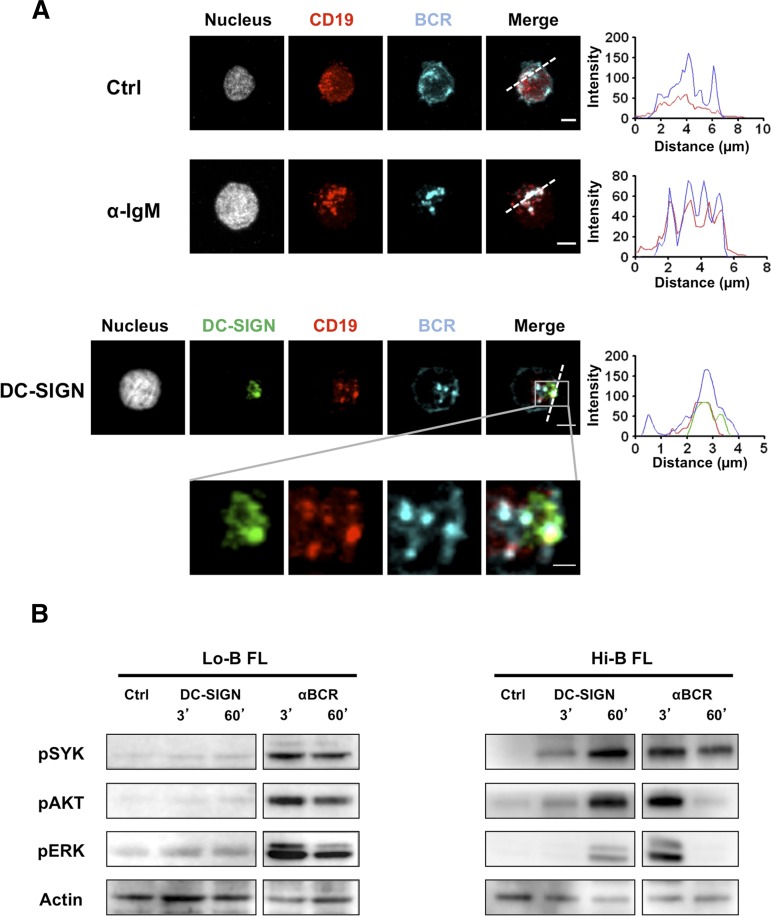

To visualize the functional consequence of DC-SIGN binding on IgM+ FL B cells, we incubated purified FL B cells with rhDC-SIGN before adhesion to fibronectin-coated glass. We confirmed the lack of DC-SIGN binding on IgM+ normal GC B cells whereas IgM+ FL B cells exhibited a DC-SIGN staining that was directly correlated to the fluorescence intensity obtained by flow cytometry (Figure 3; supplemental Figure 7). In particular, at a cell-per-cell basis, DC-SIGN binding was significantly higher for the 4 Hi-B than for the 6 Lo-B FL tested. Moreover, the accumulation of DC-SIGN on Hi-B FL B cells overlapped with BCR clusters, suggesting that DC-SIGN/BCR interaction could mimic the formation of functional signaling platforms that classically result from antigen-dependent BCR engagement. To confirm these data, we evaluated whether CD19 was associated with BCR after anti-IgM-mediated vs DC-SIGN–dependent BCR aggregation. As expected, IgM engagement induced relocalization of BCR and CD19 into BCR signalosomes. Interestingly, incubation of purified IgM+ Hi-B FL B cells with rhDC-SIGN was sufficient to promote the colocalization of DC-SIGN, CD19, and BCR (Figure 4A). Such results argue for the direct induction of organized BCR signaling platforms on IgM+ FL B cells by DC-SIGN. Finally, whereas anti-IgM triggered a strong and quick activation of SYK, AKT, and ERK in all IgM+ FL samples, Hi-B FL cell response to bead-bound DC-SIGN was clearly stronger than that obtained for Lo-B samples and was delayed but sustained compared with IgM crosslinking by anti-μ Ab (Figure 4B). As expected, IgG+ FL samples were poorly activated by DC-SIGN (supplemental Figure 8). Altogether, binding of soluble DC-SIGN to highly mannosylated IgM BCR could induce BCR aggregation and signaling in primary FL cells.

Figure 3.

Clustering of BCR and DC-SIGN in FL B cells. Sorted CD44−IgD− GC B cells and purified IgM+ FL B cells were incubated with unlabeled rhDC-SIGN before incubation on fibronectin-coated glass and fixation. DC-SIGN was revealed using mouse IgG2b anti-human DC-SIGN primary mAb and A488-donkey anti-mouse IgG2b secondary Ab whereas IgM+ cells were directly stained using A549-goat anti-IgM Ab. One example highlighting DC-SIGN/BCR colocalization is shown in panel A. Scale bar, 2.5 µM. The DC-SIGN:IgM rMFI was obtained for 100 cells per sample in 3 pooled GC B-cell samples, 6 IgM+ Lo-B FL samples (FL1, FL6-10), and 4 IgM+ Hi-B FL samples (FL3, FL5, FL11, FL12) (B). The Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test followed by the Dunn posttest was used to compare FL samples with GC-M samples; ***P < .0001.

Figure 4.

Induction of BCR signaling by DC-SIGN in FL B cells. (A) Purified Hi-B FL B cells were incubated with mouse IgG1 anti-human CD19 mAb alone (Ctrl) or before stimulation with mouse IgG3 anti-IgM mAb (αIgM) or rhDC-SIGN. After fixation, cells were stained with A594-goat anti-mouse IgG1 Ab, A647 goat anti-human IgM Ab, and, when appropriate, mouse IgG2b anti-DC-SIGN primary mAb and A488-donkey anti-mouse IgG2b secondary Ab. Shown is 1 experiment representative of 3. Scale bar, 2.5 µM. (B) Purified B cells from Lo-B FL and Hi-B FL samples were stimulated for the indicated time points with uncoated Dynabeads (Ctrl), mouse IgG3 anti-IgM mAb (BCR), or Dynabeads coated by rhDC-SIGN (DC-SIGN). Western blot revealed pSYK, pAKT, and pERK and were normalized using anti-β-actin. Shown is 1 experiment representative of 3.

DC-SIGN plays a key role in macrophage-dependent activation of IgM+ Hi-B FL samples

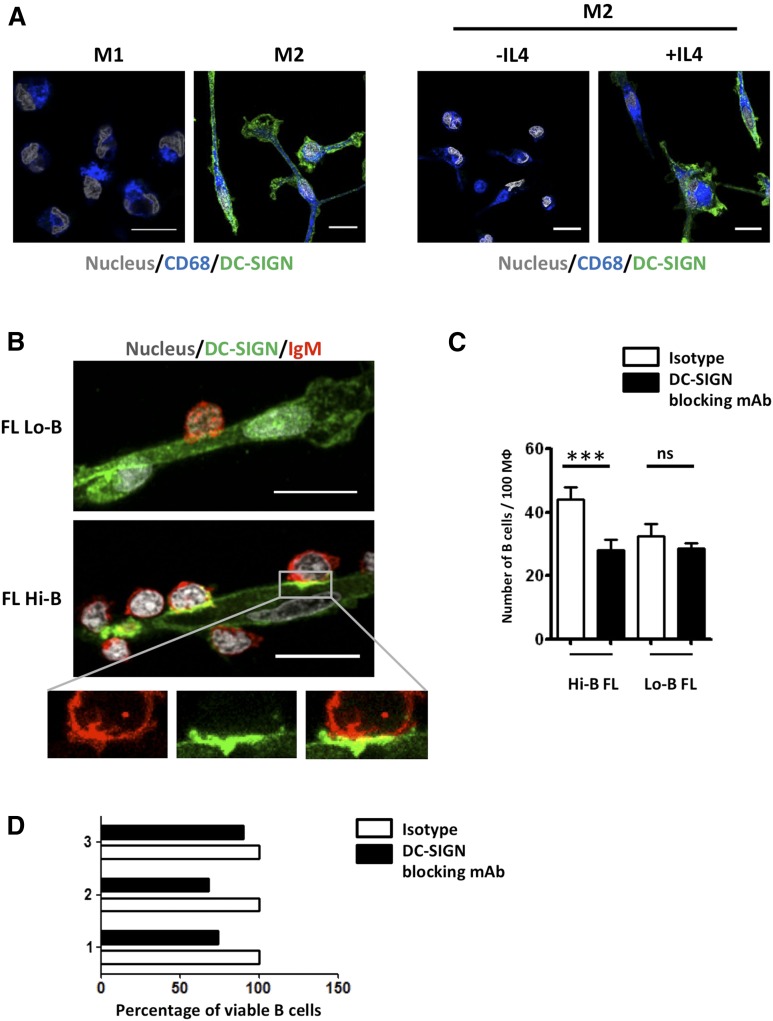

DC-SIGN supramolecular organization relies on assembly into tetramers clustered within lipid raft nanodomains on the surface of myeloid cells.20 We thus decided to explore the interaction between primary FL B cells and relevant DC-SIGN–expressing cells to take into account this functional distribution. FL-TAMs were reported to display some specific features, including a polarization into M2-like macrophages26 that could be related to the overexpression of IL-4 within FL microenvironment.27,28 We first confirmed that monocyte-derived M2, unlike M1 macrophages, strongly expressed DC-SIGN and that such expression was strictly dependent on the presence of IL-4 during in vitro differentiation29 (Figure 5A). Interestingly, only M2, and not M1, macrophages triggered ERK activation in purified IgM+ Hi-B FL B cells (supplemental Figure 9A). To further investigate the mechanism of this macrophage/B-cell interaction, we cocultured purified FL B cells and M2 macrophages. Adhesion of Hi-B FL B cells on M2 macrophages was significantly higher than observed for Lo-B and was associated with a coclustering of DC-SIGN on macrophages and BCR on B cells (Figures 5B-C; supplemental Video 1). CD19 was also relocalized at this macrophage/B-cell interface further demonstrating the formation of a functional BCR signalosome (supplemental Figure 9B).

Figure 5.

M2 macrophages trigger DC-SIGN–dependent BCR activation in FL B cells. (A) Purified CD14+ monocytes were differentiated into M1 vs M2 macrophages before staining with SytoxBlue, mouse IgG1 anti-CD68 mAb, and mouse IgG2b anti-DC-SIGN mAb. When indicated, IL-4 was omitted from terminal M2 differentiation. (B) Purified Hi-B FL and Lo-B FL B cells were cultured with M2 macrophages for 1 hour before fixation, and staining of macrophages with mouse IgG2b anti-DC-SIGN followed by A488-donkey anti-mouse IgG2b, and B cells with A549-goat anti-human IgM. Nuclei were counterstained with SytoxBlue. (C) Quantification of adherent FL B cells per 100 macrophages in the presence of anti-DC-SIGN blocking mAb or mouse IgG2b isotype control (n = 6 for Hi-B FL and n = 3 for Lo-B FL). ***P < .001. Scale bar, 15 µM. (D) Purified Hi-B FL B cells were cocultured for 24 hours with M2 macrophages in the presence of anti-DC-SIGN blocking mAb or isotype control. The percentages of CD19+Topro-3− viable B cells were then evaluated and compared with that obtained in the presence of isotype control. Three different experiments were shown.

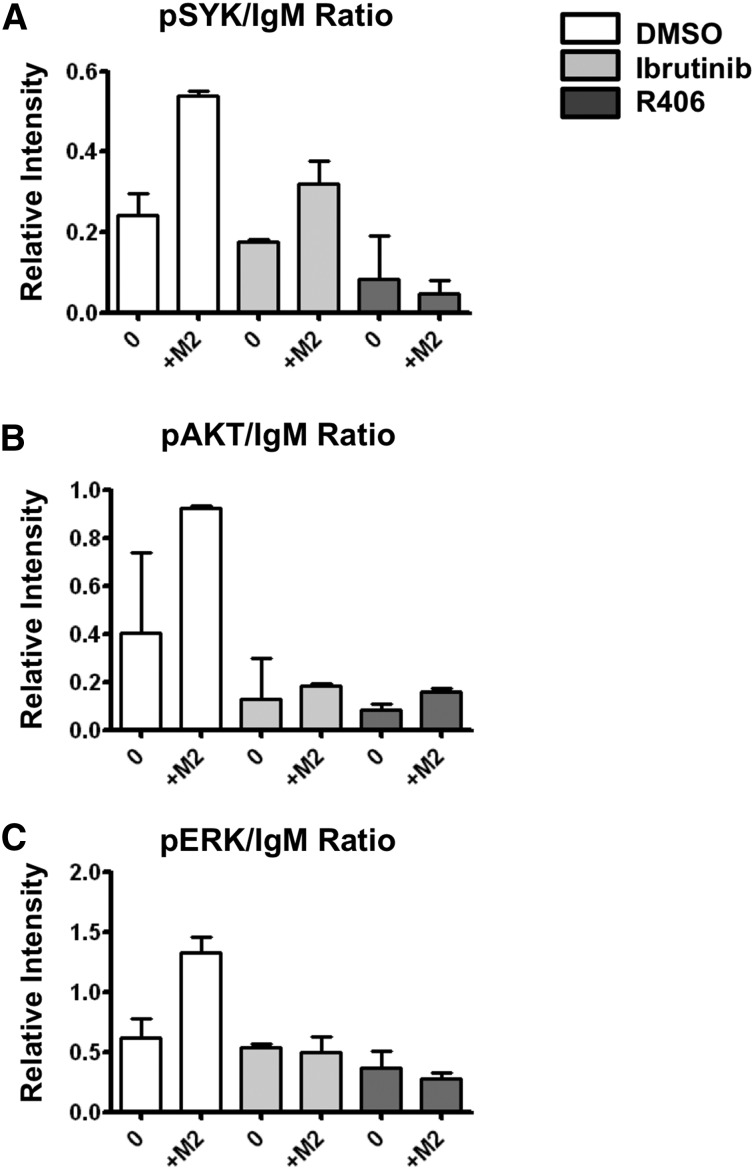

We next evaluated the role of DC-SIGN in this process and demonstrated that blocking of DC-SIGN by an antagonist antibody decreased adhesion of Hi-B FL B cells on M2 macrophages to that seen with Lo-B FL B cells, whereas it had no impact on adhesion of Lo-B FL B cells (Figure 5B-C). Such effect was specific of DC-SIGN because the antagonist anti-MR antibody had limited activity (supplemental Figure 9C). In agreement, MR did not colocalize with BCR at the contact zone between B cells and macrophages (supplemental Figure 9D). Moreover, DC-SIGN blocking decreased the previously described30 antiapoptotic activity of macrophages on 3 Hi-B FL B-cell samples, underlying the role of DC-SIGN in malignant B-cell growth (Figure 5D). Finally, we assessed whether clinical inhibitors of BCR signaling could interfere with macrophage/B-cell crosstalk. When Hi-B FL B cells were pretreated with the BTK inhibitor (Ibrutinib) or the SYK inhibitor (R406), M2-dependent B-cell activation was strongly reduced (Figure 6). In conclusion, DC-SIGN is involved in the crosstalk between M2 macrophages and B cells that could be targeted by BCR inhibitors.

Figure 6.

Btk and Syk inhibitors abrogate FL BCR activation induced by M2 macrophages. Purified Hi-B FL cells were pretreated with Ibrutinib, R406, or their solvent (DMSO) before coculture or not (0) with M2 macrophages (M2) for 1 hour. B cells were then collected and (A) pSYK, (B) pAKT, (C) pERK, and IgM expressions were studied by western blot. Bars represent mean ± SD from 2 experiments.

Discussion

It has long been assumed that malignant FL B cells co-opt BCR signaling to promote their growth and survival. In agreement, the BCR activation pathway has become a highly promising therapeutic target as emphasized by the ongoing BCR inhibitor-based clinical trials.31 The main objective of this study was to better understand how FL BCR could be activated within tumor cell niches and what the main determinants of FL heterogeneous response to BCR triggering are.

Both IgM+ and IgG+ FL B cells responded vigorously to BCR crosslinking in the presence of the phosphatase inhibitor H2O2, thus mimicking their normal GC B-cell counterpart. In fact, as previously described in mice,9,10 human GC B cells exhibited a limited capacity to elicit BCR activation due to high phosphatase activity. Interestingly, only IgM+ FL B cells demonstrated significant BCR signaling in steady-state condition. Several nonexclusive possibilities could explain such differences in IgM vs IgG FL BCR signaling. First, even if the expression of the main BCR-related phosphatases was not different between IgM+ and IgG+ FL, other factors influencing phosphatase activity could be involved. In particular, the high phosphatase activity found in mouse GC B cells is related to the lack of dissociation of Src homology region 2-domain phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) and Sh2-containing inositol phosphatase 1 (SHIP-1) from BCR in response to BCR ligation and not to an increase of SHP-1 and SHIP-1 expression or phosphorylation.9 How IgM vs IgG FL B cells exhibit various capacities to interact with BCR-related phosphatases deserves further studies. Second, the level of surface BCR could play an important role in favor of stronger responsiveness of IgM+ FL B cells. Interestingly, IL-4, the main cytokine overexpressed within the FL microenvironment,27 has been recently demonstrated to upregulate surface IgM expression on mouse naive B cells leading to an amplification of BCR-triggered phosphorylation events, whereas expression of surface IgD was differentially regulated.32 Strikingly, we pinpointed that IL-4 increased surface BCR expression in vitro in 3 IgM+ FL samples unlike in 3 IgG+ FL samples (data not shown). It is tempting to speculate that IL-4, produced in situ by FL-TFH,28,33 could contribute to the maintenance of a high level of surface IgM on FL B cells. Finally, the fact that IgG FL BCRs preferentially recognize autoantigens whereas IgM FL BCR display less autoreactivity11 but more efficient interaction with C-type lectins could be associated with a higher affinity for antigen, stronger BCR signaling, and a resulting BCR desensitization in IgG+ FL samples.34 Interestingly, whereas FL B cells are permanently driven to class-switch recombination, selective pressure retains surface IgM expression from the productive allele in a majority of cases,18,19 suggesting a growth advantage for the expression of IgM.20 The unique cytoplasmic tails of IgM and IgG BCR produce qualitatively different signaling outputs in antigen-experienced B cells.35 In particular, switched memory B cells are prone to generate a large number of plasma cells whereas IgM+ memory B cells reinitiate a GC reaction upon antigenic challenge.36,37 The maintenance of IgM BCR could thus contribute to the frozen GC phenotype of FL B cells that is established very early during lymphomagenesis process and is associated with a high risk of additional genetic events.38,39

Unlike normal GC B cells, FL B cells were able to bind soluble DC-SIGN.16 However, staining intensity was heterogeneous and we identified a subset of IgM+ FL samples with a strong capacity to interact with DC-SIGN that triggered in turn an antigen-independent BCR aggregation and signaling. These Hi-B FL samples exhibited a specific high mannose-rich BCR glycosylation pattern. Of note the DC-SIGN–driven signaling was delayed but long lasting compared with anti-Ig-driven activation. This could be at least in part explained by the lack of BCR endocytosis after engagement by DC-SIGN.40 Even if several lectins could mediate FL BCR activation in vitro,17 DC-SIGN is a very good candidate as an endogenous FL BCR ligand. First, DC-SIGN was overexpressed on myeloid cells within FL cell niches, in agreement with the poor prognosis of a high TAM content in FL patients treated by chemotherapy.23 DC-SIGN staining in situ revealed both CD68+ cells and lymphatic endothelial cells in FL samples. Interestingly, the DCN46 Ab commonly used to detect DC-SIGN was recently shown to stain not only DC-SIGN+ antigen-presenting cells in the paracortex and sinuses, but also CD299/L-SIGN+ lymphatic endothelial cells in human lymph nodes.41 L-SIGN is a close homolog to DC-SIGN and interacts with the same ligands including high-mannose glycans.20 Because FL is a disseminated disease,42,43 L-SIGN expressed by lymphatic endothelial cells may also interact with malignant FL B cells and contribute either to BCR signaling or to the dissemination of the disease.

Besides the interaction with soluble DC-SIGN, we reported here for the first time the direct BCR- and DC-SIGN–dependent crosstalk between M2 macrophages and FL B cells. Interestingly, blockade of MR did not abrogate the increased adhesion of IgM+ Hi-B FL B cells to macrophages. This could be related to the preferential intracellular accumulation of MR whereas DC-SIGN is essentially expressed at the cell membrane (Gazi and Martinez-Pomares44 and data not shown). Moreover, we confirmed that DC-SIGN is inducible on macrophages by IL-4, making this cytokine a central effector of macrophage/B-cell crosstalk through the combined upregulation of IgM and DC-SIGN. We previously demonstrated that IL-4 is specifically overexpressed by a subset of CD10+-infiltrating FL follicular helper T cells (TFH)33 and triggers direct signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 6–dependent antiapoptotic activity on malignant FL B cells.28,45 Our current results further suggest that IL-4 could also display indirect protumoral activity by promoting TAM polarization and B-cell supportive activity. Altogether, monocytes could be recruited within the FL tumor niche through the production of CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) by infiltrating stromal cells30 and are committed in situ to tumor-supportive TAMs in response to various stimuli including TFH-derived IL-4.44 FL TAM will then favor malignant B-cell growth, by the production of IL-15,46 B-cell activating factor,47,48 and DC-SIGN, and through angiogenic and immunosuppressive properties.26,49

Recently, BCR inhibitors have gained considerable interest because of their effectiveness in several B-cell lymphoma subtypes. Interestingly, their efficacy relies not only on the direct blockade of BCR-mediated B-cell survival but also on their capacity to abrogate the BCR-dependent activation of integrins and increase of chemotaxis.50 We demonstrated here that such inhibitors could strongly affect the crosstalk between B cells and macrophages, reinforcing their interest even in diseases where the BCR pathway is not constitutively activated by genetic alterations but required engagement by external stimuli. Other therapeutic approaches designed to selectively block interaction between DC-SIGN and high-mannose residues would also be of potential relevance in FL patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the Centre de Ressources Biologiques (CRB)-Santé (BB-0033-00056, http://www.crbsante-rennes.com) of Rennes Hospital for its support in the processing of biological samples, Christophe Ruaux for providing tonsil samples, and Delphine Rossille for helpful statistical analysis advices. The immunofluorescence study was performed at the Microscopy Rennes Imaging Center (MRic-ALMF; UMS 6480 Biosit, Rennes, France).

This work was supported by research grants from the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée and “Carte d’identité des Tumeurs” program) and the Association pour la Recherche Contre le Cancer (ARC AO 2011).

R.A. is the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fonds Européens de Développement Régional (FEDER), the Contrat de plan Etat région Bretagne, axe Biothérapie (CPER), and the Association pour le Développement de l’Hémato-Oncologie (ADHO).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: R.A. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and contributed writing; F.M., F.U., C.P., M.G., and P.R. performed experiments and analyzed data; L.D. contributed vital new tools; T.M. and T.F. provided samples and clinical data; T.L. provided samples and helped raising funds; and K.T. designed and supervised research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Karin Tarte, Faculté de Médecine, INSERM, Unité Mixte de Recherche U917, 2 Avenue du Pr Léon Bernard, F-35043 Rennes, France; e-mail: karin.tarte@univ-rennes1.fr.

References

- 1.Amé-Thomas P, Tarte K. The yin and the yang of follicular lymphoma cell niches: role of microenvironment heterogeneity and plasticity. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;24:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott DW, Gascoyne RD. The tumour microenvironment in B cell lymphomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(8):517–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc3774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuckerman NS, McCann KJ, Ottensmeier CH, et al. Ig gene diversification and selection in follicular lymphoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma and primary central nervous system lymphoma revealed by lineage tree and mutation analyses. Int Immunol. 2010;22(11):875–887. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeffler M, Kreuz M, Haake A, et al. HaematoSys-Project. Genomic and epigenomic co-evolution in follicular lymphomas. Leukemia. 2015;29(2):456–463. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meeker T, Lowder J, Cleary ML, et al. Emergence of idiotype variants during treatment of B-cell lymphoma with anti-idiotype antibodies. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(26):1658–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506273122602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raffeld M, Neckers L, Longo DL, Cossman J. Spontaneous alteration of idiotype in a monoclonal B-cell lymphoma. Escape from detection by anti-idiotype. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(26):1653–1658. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506273122601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irish JM, Czerwinski DK, Nolan GP, Levy R. Altered B-cell receptor signaling kinetics distinguish human follicular lymphoma B cells from tumor-infiltrating nonmalignant B cells. Blood. 2006;108(9):3135–3142. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irish JM, Myklebust JH, Alizadeh AA, et al. B-cell signaling networks reveal a negative prognostic human lymphoma cell subset that emerges during tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(29):12747–12754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002057107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalil AM, Cambier JC, Shlomchik MJ. B cell receptor signal transduction in the GC is short-circuited by high phosphatase activity. Science. 2012;336(6085):1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1213368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller J, Matloubian M, Zikherman J. Cutting edge: an in vivo reporter reveals active B cell receptor signaling in the germinal center. J Immunol. 2015;194(7):2993–2997. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cha SC, Qin H, Kannan S, et al. Nonstereotyped lymphoma B cell receptors recognize vimentin as a shared autoantigen. J Immunol. 2013;190(9):4887–4898. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachen KL, Strohman MJ, Singletary J, et al. Self-antigen recognition by follicular lymphoma B-cell receptors. Blood. 2012;120(20):4182–4190. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-427534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu D, McCarthy H, Ottensmeier CH, Johnson P, Hamblin TJ, Stevenson FK. Acquisition of potential N-glycosylation sites in the immunoglobulin variable region by somatic mutation is a distinctive feature of follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2002;99(7):2562–2568. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radcliffe CM, Arnold JN, Suter DM, et al. Human follicular lymphoma cells contain oligomannose glycans in the antigen-binding site of the B-cell receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(10):7405–7415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mamessier E, Drevet C, Broussais-Guillaumot F, et al. Contiguous follicular lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in situ harboring N-glycosylated sites. Haematologica. 2015;100(4):e155–e157. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.115782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coelho V, Krysov S, Ghaemmaghami AM, et al. Glycosylation of surface Ig creates a functional bridge between human follicular lymphoma and microenvironmental lectins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(43):18587–18592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009388107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider D, Dühren-von Minden M, Alkhatib A, et al. Lectins from opportunistic bacteria interact with acquired variable-region glycans of surface immunoglobulin in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(21):3287–3296. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-609404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaandrager JW, Schuuring E, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Dyer MJ, Raap AK, Kluin PM. DNA fiber fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of immunoglobulin class switching in B-cell neoplasia: aberrant CH gene rearrangements in follicle center-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1998;92(8):2871–2878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruminy P, Jardin F, Penther D, et al. Recurrent disruption of the Imu splice donor site in t(14;18) positive lymphomas: a potential molecular basis for aberrant downstream class switch recombination. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(8):735–744. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Vallejo JJ, van Kooyk Y. The physiological role of DC-SIGN: a tale of mice and men. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(10):482–486. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez-Pomares L. The mannose receptor. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;92(6):1177–1186. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0512231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dave SS, Wright G, Tan B, et al. Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(21):2159–2169. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farinha P, Masoudi H, Skinnider BF, et al. Analysis of multiple biomarkers shows that lymphoma-associated macrophage (LAM) content is an independent predictor of survival in follicular lymphoma (FL). Blood. 2005;106(6):2169–2174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byers RJ, Sakhinia E, Joseph P, et al. Clinical quantitation of immune signature in follicular lymphoma by RT-PCR-based gene expression profiling. Blood. 2008;111(9):4764–4770. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Segura E, Durand M, Amigorena S. Similar antigen cross-presentation capacity and phagocytic functions in all freshly isolated human lymphoid organ-resident dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210(5):1035–1047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clear AJ, Lee AM, Calaminici M, et al. Increased angiogenic sprouting in poor prognosis FL is associated with elevated numbers of CD163+ macrophages within the immediate sprouting microenvironment. Blood. 2010;115(24):5053–5056. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calvo KR, Dabir B, Kovach A, et al. IL-4 protein expression and basal activation of Erk in vivo in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2008;112(9):3818–3826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-138933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pangault C, Amé-Thomas P, Ruminy P, et al. Follicular lymphoma cell niche: identification of a preeminent IL-4-dependent T(FH)-B cell axis. Leukemia. 2010;24(12):2080–2089. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domínguez-Soto A, Sierra-Filardi E, Puig-Kröger A, et al. Dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin expression on M2-polarized and tumor-associated macrophages is macrophage-CSF dependent and enhanced by tumor-derived IL-6 and IL-10. J Immunol. 2011;186(4):2192–2200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guilloton F, Caron G, Ménard C, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells orchestrate follicular lymphoma cell niche through the CCL2-dependent recruitment and polarization of monocytes. Blood. 2012;119(11):2556–2567. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-370908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young RM, Staudt LM. Targeting pathological B cell receptor signalling in lymphoid malignancies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):229–243. doi: 10.1038/nrd3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo B, Rothstein TL. IL-4 upregulates Igα and Igβ protein, resulting in augmented IgM maturation and B cell receptor-triggered B cell activation. J Immunol. 2013;191(2):670–677. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amé-Thomas P, Hoeller S, Artchounin C, et al. CD10 delineates a subset of human IL-4 producing follicular helper T cells involved in the survival of follicular lymphoma B cells. Blood. 2015;125(15):2381–2385. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-625152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horikawa K, Martin SW, Pogue SL, et al. Enhancement and suppression of signaling by the conserved tail of IgG memory-type B cell antigen receptors. J Exp Med. 2007;204(4):759–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laffleur B, Denis-Lagache N, Péron S, Sirac C, Moreau J, Cogné M. AID-induced remodeling of immunoglobulin genes and B cell fate. Oncotarget. 2014;5(5):1118–1131. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dogan I, Bertocci B, Vilmont V, et al. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(12):1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Jenkins MK. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331(6021):1203–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sungalee S, Mamessier E, Morgado E, et al. Germinal center reentries of BCL2-overexpressing B cells drive follicular lymphoma progression. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(12):5337–5351. doi: 10.1172/JCI72415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tellier J, Menard C, Roulland S, et al. Human t(14;18)positive germinal center B cells: a new step in follicular lymphoma pathogenesis? Blood. 2014;123(22):3462–3465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-12-545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linley AL, Krysov S, Ponzoni M, Johnson PW, Packham G, Stevenson FK. Lectin binding to surface Ig variable regions provides a universal persistent activating signal for follicular lymphoma cells [published online ahead of print July 20, 2015]. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-04-640805. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-04-640805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park SM, Angel CE, McIntosh JD, et al. Mapping the distinctive populations of lymphatic endothelial cells in different zones of human lymph nodes [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e106814]. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wartenberg M, Vasil P, zum Bueschenfelde CM, et al. Somatic hypermutation analysis in follicular lymphoma provides evidence suggesting bidirectional cell migration between lymph node and bone marrow during disease progression and relapse. Haematologica. 2013;98(9):1433–1441. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.074252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mourcin F, Pangault C, Amin-Ali R, Amé-Thomas P, Tarte K. Stromal cell contribution to human follicular lymphoma pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2012;3:280. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gazi U, Martinez-Pomares L. Influence of the mannose receptor in host immune responses. Immunobiology. 2009;214(7):554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amé-Thomas P, Le Priol J, Yssel H, et al. Characterization of intratumoral follicular helper T cells in follicular lymphoma: role in the survival of malignant B cells. Leukemia. 2012;26(5):1053–1063. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Epron G, Ame-Thomas P, Le Priol J, et al. Monocytes and T cells cooperate to favor normal and follicular lymphoma B-cell growth: role of IL-15 and CD40L signaling. Leukemia. 2012;26(1):139–148. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mueller CG, Boix C, Kwan WH, et al. Critical role of monocytes to support normal B cell and diffuse large B cell lymphoma survival and proliferation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(3):567–575. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0706481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novak AJ, Slager SL, Fredericksen ZS, et al. Genetic variation in B-cell-activating factor is associated with an increased risk of developing B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69(10):4217–4224. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carbonnelle-Puscian A, Copie-Bergman C, Baia M, et al. The novel immunosuppressive enzyme IL4I1 is expressed by neoplastic cells of several B-cell lymphomas and by tumor-associated macrophages. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):952–960. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shain KH, Tao J. The B-cell receptor orchestrates environment-mediated lymphoma survival and drug resistance in B-cell malignancies. Oncogene. 2014;33(32):4107–4113. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]