Abstract

Dental enamel formation requires large quantities of Ca2+ yet the mechanisms mediating Ca2+ dynamics in enamel cells are unclear. Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) channels are important Ca2+ influx mechanisms in many cells. SOCE involves release of Ca2+ from intracellular pools followed by Ca2+ entry. The best-characterized SOCE channels are the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels. As patients with mutations in the CRAC channel genes STIM1 and ORAI1 show abnormal enamel mineralization, we hypothesized that CRAC channels might be an important Ca2+ uptake mechanism in enamel cells. Investigating primary murine enamel cells, we found that key components of CRAC channels (ORAI1, ORAI2, ORAI3, STIM1, STIM2) were expressed and most abundant during the maturation stage of enamel development. Furthermore, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) but not ryanodine receptor (RyR) expression was high in enamel cells suggesting that IP3Rs are the main ER Ca2+ release mechanism. Passive depletion of ER Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin resulted in a significant raise in [Ca2+]i consistent with SOCE. In cells pre-treated with the CRAC channel blocker Synta-66 Ca2+ entry was significantly inhibited. These data demonstrate that enamel cells have SOCE mediated by CRAC channels and implicate them as a mechanism for Ca2+ uptake in enamel formation.

Ca2+ is one of the most abundant elements in mineralized enamel yet the mechanisms allowing the flow of Ca2+ from the blood stream to the enamel space during development are poorly understood. Ameloblasts are polarized cells responsible for the regulation of Ca2+ transport during enamel formation. These cells form an epithelial barrier restricting the free flow of Ca2+ into the enamel layer where hydroxyapatite-like crystals are growing1,2. Thus ameloblasts handle large quantities of Ca2+ and to avoid toxicity, these cells must tightly regulate Ca2+ influx and buffering, organellar Ca2+ release and sequestration, and Ca2+ extrusion. Ameloblasts express Ca2+ binding proteins in the cytoplasm and ER2,3,4,5,6,22, with the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases (SERCAs) pumps being involved in ER Ca2+ sequestration thus contributing to cytosolic Ca2+ buffering7. Extrusion mechanisms in ameloblasts include plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases (PMCA) as well as K+-dependent and K+-independent Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCKX and NCX, respectively)7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Despite the critical role of Ca2+ in the formation of hydroxyapatite-like crystals, our understanding of the mechanisms employed by ameloblasts to mediate Ca2+ uptake and transport remains limited although biochemical data has suggested a “transcytosis” route for Ca2+ being channelled across the cell within the ER2,22,41.

Recent evidence gathered by our group first identified one of the components of the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel protein STIM1 in murine enamel organ cells from a genome wide study15. CRAC channels mediate SOCE, which is an important Ca2+ influx pathway in non-excitable and excitable cells that is activated following Ca2+ release from the ER16,17. Depletion of ER Ca2+ causes the ER resident proteins STIM1 and STIM2 to interact with ORAI proteins, which form the pore of the CRAC channel in the plasma membrane, enabling localized and sustained Ca2+ entry17,18,19. Recent reports have described enamel pathologies in patients with null mutation in STIM1 and ORAI1 genes, which are characterized by severely hypo-mineralized enamel13,20,21. These important clinical findings suggest that CRAC channels might be a key mechanism for Ca2+ uptake during enamel formation.

Enamel develops largely in two stages, the secretory and maturation stages. The continuously growing rodent incisor is an ideal model to study enamel development as a population of cells from both stages can be identified through life. In the secretory stage, ameloblasts are involved in the synthesis and secretion of enamel-specific proteins, forming an organic template for the growth of thin enamel crystals1. During maturation, evidence suggests an increase in the transport capacity of enamel cells, mainly Ca2+ and phosphate, which are moved to the extracellular domain to supersaturate the enamel fluid and enable a vast increase in thickness of the enamel crystals1,3,15,22,23,24. The aim of our previous genome wide study was to provide a global overview of the cellular machinery required for the mineralization of enamel15. Bioinformatic analysis identified murine Stim1 and Stim2 genes as up-regulated transcripts in the maturation stage and we further confirmed these results by Western blot analysis of STIM1 and STIM2 proteins. The present study explores whether secretory stage enamel organ (SSEO) and maturation stage enamel organ (MSEO) cells are equipped with components essential to increases in Ca2+ handling capacity, and tests whether Ca2+ entry in SSEO and MSEO cells is mediated by CRAC channels.

Results

Identification of ER-Ca2+ release channels and ER-Ca2+ refilling pumps

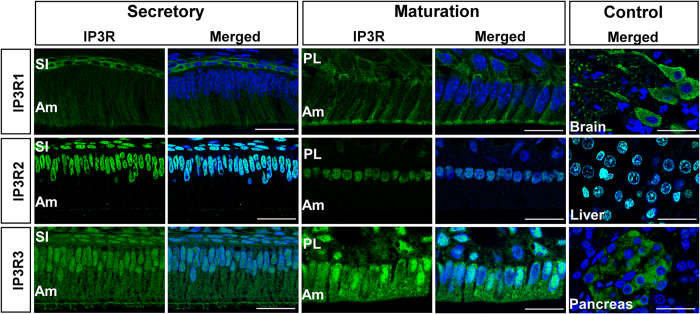

Transient increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) can be mediated by the release of Ca2+ from ER stores via IP3Rs or/and RyRs25. Transcripts of all IP3R isoforms were identified in rat secretory stage enamel organ and maturation stage enamel organ cells by RT-PCR, however, RyRs expression levels were negligible compared to those of the IP3R transcripts (data not shown). This was also evident by immunofluorescence staining of the RyR proteins which showed very weak signals (Supplementary Fig. S1) and hence we turned our attention to the expression of IP3R isoforms as shown in Fig 1. IP3R1 reactivity was detected in the intracellular compartment of secretory and maturation stage ameloblasts (Fig. 1, upper panel) but reactivity appeared to increase at the apical pole of maturation stage ameloblasts. IP3R2 localized only in the nuclei of secretory and maturation stage ameloblasts (Fig. 1, middle panel). These data are consistent with a previous report on the nuclear localization of IP3R2 in endothelial cells26. IP3R3 showed an intracellular localization in both secretory and maturation stage rat ameloblasts although reactivity was higher in the latter. Weak nuclear staining was also detected for IP3R3 in both stages (Fig. 1, lower panel). Other cell types part of the enamel organ which may also participate in transport functions such as stratum intermedium (SI) cells in secretory stage, and papillary layer (PL) cells during maturation stage, also showed positive staining for the IP3R proteins (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Localization of IP3R isoforms in ameloblasts.

Upper panel shows IP3R1 (green) immunolocalization and nuclear DAPI (blue) staining in rat secretory and maturation ameloblasts. Brain (rat) was used as a positive control. IP3R1 is localized intracellularly as also seen in the cells of the stratum intermedium adjacent to secretory ameloblasts. In maturation stage, the papillary layer replaces the stratum intermedium. Middle panel shows IP3R2 (green) immunolocalization and DAPI (blue) in rat secretory and maturation stage ameloblasts. IP3R2 is localized to the cell nuclei. Rat liver was used as a positive control. Lower panel shows IP3R3 (green) immunolocalization and DAPI (blue) in rat secretory and maturation ameloblasts showing intracellular localization with stronger signal in maturation stage ameloblasts. Pancreas was used as a positive control. Am = ameloblasts; PL = papillary layer; SI = stratum intermedium cells. Scale bars in all images = 20 μm.

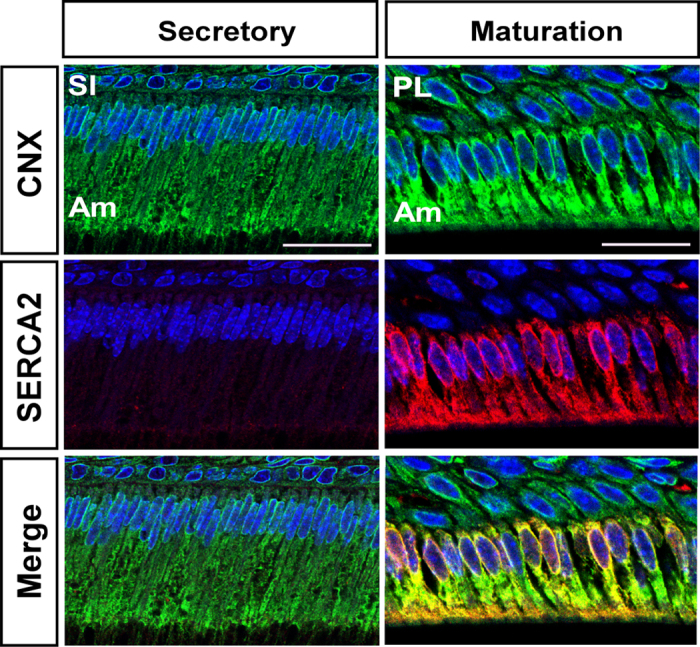

Refilling ER Ca2+ stores is mediated by SERCA pumps that sequester cytosolic Ca2+ into the ER lumen27. The murine genes coding for the SERCA isoforms are Atp2a1, Atp2a2, Atp2a3. A previous study had reported on high protein levels for SERCA2 in maturation stage enamel cells7. Consistent with those results, here we identified abundant mRNA levels of SERCA2 (Atp2a2) by RT-PCR in maturation stage enamel organ cells, which was also the predominant isoform (Supplementary Fig. S2). We therefore investigated SERCA2 localization in ameloblasts by confocal microscopy (Fig. 2). In secretory ameloblasts, SERCA2 signals (red fluorescence) were almost absent, but in maturation stage ameloblasts, SERCA2 was very prominent showing an intracellular localization coinciding with the distribution of the ER as shown by the expression of the ER marker calnexin (CNX). Western blot analysis showed an increase in expression of SERCA2 from secretory to maturation stage (Supplementary Fig. S3). These data confirm that required ER-Ca2+ release channels and luminal ER-Ca2+ refilling pumps are not only present in both stages of enamel development, but are also up-regulated during the calcium-transport intensive stage (maturation).

Figure 2. Localization of SERCA2 in ameloblasts.

SERCA2 was almost absent in secretory stage ameloblasts but maturation ameloblasts showed strong signals localized to the cytoplasm. SERCA2 expression closely coincides with the localization of the ER as shown by the expression of the ER marker calnexin (CNX). SERCA2 are pumps involved in the transport of Ca2+ from the cytosol into the ER lumen. Am = ameloblasts; PL = papillary layer; SI = stratum intermedium cells. Scale bars in all images = 20 μm.

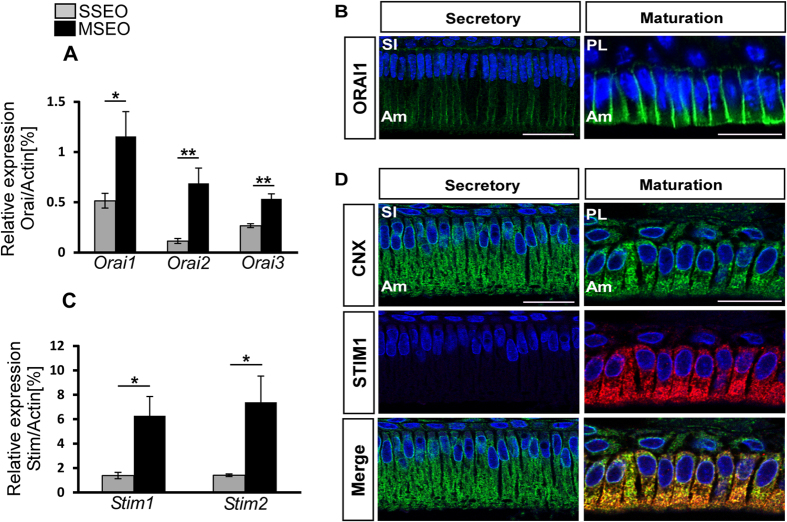

STIM and ORAI expression and localization in ameloblasts

We then looked for evidence of the molecular components of CRAC channel and identified mRNA expression of all murine Stim and Orai isoforms in secretory and maturation stage enamel organ cells by RT-PCR (Fig. 3). Comparing mRNA differences between stages we found that all three Orai and both Stim1 and Stim2 transcripts were more abundant in maturation than secretory stage cells (Fig. 3A,C). These data for Stim1 and Stim2 are consistent with our previous gene array and Western blot analysis15. As human patients with mutations in STIM1 and ORAI1 genes have severely hypo-calcified enamel13,20,21 we focused our attention on the localization of these two proteins in enamel cells. Immunofluorescence studies on paraffin sections of secretory stage ameloblasts showed ORAI1 localized to the basal (supranuclear) and lateral regions of the cells (Fig. 3B). Maturation stage ameloblasts showed stronger ORAI1 immunofluorescence localized at the basolateral pole of the cells consistent with a role of CRAC channels in SOCE (Fig. 3B). In contrast, STIM1 was barely detected in secretory ameloblasts (Fig. 3D) but was strongly expressed in maturation stage cells and showed widespread localization within the cell. STIM1 expression overlapped with the localization of the ER, as shown by the cellular staining of ER marker CNX (Fig. 3D). These data confirm that the molecular components of CRAC channels are expressed in enamel cells. Their cellular localization is consistent with their expected roles as ER Ca2+ sensor (STIM1) and pore subunit (ORAI1) of the CRAC channel. We also examined the contribution of STIM2 and investigated its localization by immunoperoxidase staining. STIM2 protein was expressed in both secretory and maturation ameloblasts with stronger signals in maturation (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 3. ORAI and STIM1 expression and localization in enamel cells.

(A,C) Relative quantification of Orai (1–3) and Stim (1–2) transcript levels in SSEO (grey bars) and MSEO (black bars). For RT-PCR, actin was used as a reference gene. Significance was established using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01). Each experiment was repeated at least three times. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy showing the cellular localization of ORAI1 (green) in the plasma membrane of mouse secretory and maturation ameloblasts. (D) Confocal microscopy showing localization of STIM1 (red) and the endoplasmic reticulum marker calnexin (CNX, green) in rat maturation and secretory ameloblasts. Overlay of STIM1 and CNX is shown in the lower panel (merge). DAPI is shown as blue nuclear staining. Am = ameloblasts; PL = papillary layer; SI=stratum intermedium cells. Scale bars in all images = 20 μm.

Ca2+ entry in enamel cells is mediated by CRAC channels

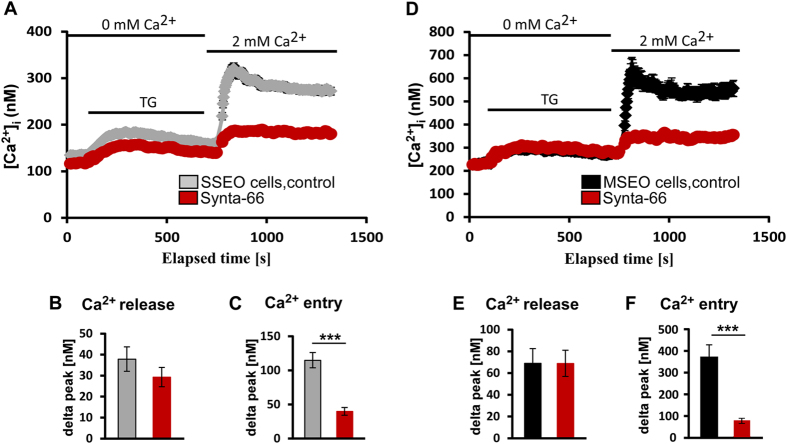

Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured by loading secretory and maturation stage enamel cells with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator dye Fura-2-AM. Basal cytosolic Ca2+ levels for secretory and maturation stage enamel cells were measured prior to thapsigargin stimulation. We found significantly higher basal cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations (p < 0.05, Student’s t-test) in maturation stage enamel cells (~230 nM) compared to secretory stage enamel cells (~135 nM) (Fig. 4, see also Supplementary Fig. S5). Depletion of Ca2+ stores activates SOCE mediated by CRAC channels. We thus stimulated enamel cells with thapsigargin (1.25 μM) to block SERCA, a procedure that depletes Ca2+ from ER stores through poorly understood ER leaks28. Thapsigargin is commonly used for activating SOCE in many cell types29,30. Thapsigargin was first applied in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ resulting in increased levels in [Ca2+]i due to Ca2+ release from ER stores (Fig. 4A,B). We found that in secretory stage cells, ER Ca2+ release increased [Ca2+]i by ~40 nM. In maturation stage cells this increase was in the order of ~70 nM.

Figure 4. CRAC channels mediate Ca2+ entry in enamel cells.

(A) Ca2+dynamics in secretory stage enamel organ (SSEO) cells. SSEO cells were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2 AM and pretreated with Synta-66 (3 μM) (red traces) or left untreated (gray traces). Graphs represent means of [Ca2+]i (in nM) calculated from the means of F340/F380 Fura-2 fluorescence ratios recorded in SSEO cells. SSEO cells were stimulated with thapsigargin (1.25 μM) to deplete ER stores resulting in an increase in [Ca2+]i. Following readdition of extracellular Ca2+ (resulting in a final extracellular [Ca2+] of 2 mM), we observed a marked increase in [Ca2+]i but in Synta-66 treated SSEO cells this [Ca2+]i increase was significantly inhibited (p < 0.001, ANOVA). Panels B and C show delta peak (in nM) of ER- Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry in control cells compared to Synta-66 pretreated cells Untreated SSEO cells analyzed: n = 16 (grey bars), Synta-66 pre-treated SSEO cells: n = 8 (red bars). ***(p < 0.001), ANOVA. (D) Ca2+ dynamics in maturation stage enamel organ (MSEO) cells. Experiments were conducted as described for panel A. Untreated MSEO cells (black traces), Synta-66 pre-treated MSEO cells (red tracings). MSEO cells stimulated with thapsigargin showed an increase in [Ca2+]i. Following readdition of extracellular Ca2+ there was a marked increase in [Ca2+]i but not in Synta-66 treated MSEO cells which was significantly inhibited (p < 0.001, ANOVA). Panels E and F show delta peak (in nM) of ER- Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry in control cells compared to Synta-66 pretreated cells. Untreated MSEO cells analyzed: n = 14 (black bars); Synta-66 pre-treated MSEO cells analyzed: n = 8 (red bar). ***(p < 0.001), ANOVA.

Ca2+ entry was subsequently analyzed upon readdition of extracellular Ca2+ to the cells. We identified a significant increase (p < 0.05, Student’s t-test) in [Ca2+]i in both cell types demonstrating that enamel cells from secretory and maturation stages have SOCE. This increase in [Ca2+]i was however significantly higher in maturation stage enamel cells than in secretory stage cells (p < 0.05, Student’s t-test) (Supplementary Fig. S5). The increase in [Ca2+]i following readdition of Ca2+ was ~115 nM in secretory stage cells and ~350 nM in maturation stage cells (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S5). These data are consistent with increased expression levels of STIM and ORAI molecules at the maturation stage (Fig. 3).

CRAC channels are the prototypical SOCE channel. To test whether secretory and maturation stage enamel organ cells have functional CRAC channels, we used a specific pharmacological CRAC channel blocker (Synta-66)31 to analyse the effects on SOCE. We found that cells from the maturation and secretory stage pre-treated with Synta-66 showed significantly reduced (p < 0.001) Ca2+ influx upon readdition of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 4). These results indicate that SOCE in enamel cells is mediated by CRAC channels.

Discussion

Ca2+ transport is critical for enamel development and yet the cellular mechanisms associated with Ca2+ entry remain a central question in enamel biology. The present study demonstrates that rat secretory stage enamel organ and maturation stage enamel organ cells express SOCE with CRAC channel properties. As Ca2+ release from the ER pools is required for SOCE activation, we investigated whether enamel cells are equipped with common receptors involved in ER-Ca2+ release and to compare possible differences among them. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) are the main ER Ca2+ release mechanisms25,32. Immunofluorescence studies showed very weak signals for all RyR isoforms (Supplementary Fig. S1) but not for IP3R, revealing differences in cellular localization (Fig. 1). IP3R1 and IP3R3 showed a cytoplasmic localization whereas IP3R2 was found only in the nuclei. These expression patterns are consistent with reports for other tissues30,33 and although it is not uncommon to identify all IP3R isoforms expressed in the same cells, differences in cellular localization have been associated with the performance of various functions. The nuclear localization of IP3R2 in secretory and maturation stage ameloblasts suggests that this protein might be involved in nuclear Ca2+ signaling as observed in other cells types where this isoform is restricted to the nucleus34. The roles of IP3R1 and IP3R3 are perhaps less clear. IP3R1 showed a more limited cytoplasmic localization than the extensive cytoplasmic localization of IP3R3 in secretory and maturation stage ameloblasts. The ER has a wide distribution in both secretory and maturation stage ameloblast as observed by calnexin (CNX) signals detected in ameloblasts (Figs 2 and 3) and as also identified by electron microscopy35. Thus it appears that both proteins might be in close proximity to, and able to interact with, other Ca2+ mobilizing organelles including mitochondria, as these are found in the perinuclear region of ameloblasts35 and are up-regulated during maturation36. Such mitochondria-ER interactions are well known and play complex roles related to Ca2+ buffering, ATP production and other functions37. Alternatively, differences between IP3R1 and IP3R3 might be linked to the generation of more localized Ca2+ signals or possibly marking differences in ER compartments in ameloblasts but this needs to be explored further. Regardless, the expression of both of these receptor types produce stronger signals in maturation stage ameloblasts, an expression profile similar to that of the ER Ca2+ refilling protein SERCA2 as well as increases in STIM1, STIM2 and ORAI1.

This study identified SERCA2 as the most up-regulated of the three SERCAs in enamel cells showing a wide cytosolic expression (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. S2). These data are consistent with a previous report describing this isoform as the predominant SERCA in enamel cells7. Although the expression pattern of SERCA2 identified here by immunofluorescence shows low expression in secretory stage ameloblasts, our Western blot analysis of SERCA2 (Supplementary Fig. S3) as well as Northern blot and Western blot analysis previously reported7 reveals that SERCA2 is indeed expressed at lower levels during the secretory stage. Additionally, our Fura-2 data in secretory stage enamel cells showed increased [Ca2+]i levels after blocking SERCA with thapsigargin indicating that despite its low abundance, the function of SERCA is not absent at this stage.

Abundant evidence suggests that the requirement to transport Ca2+ increases during the maturation stage of amelogenesis1,2. In keeping with these studies we found that basal cytosolic Ca2+ levels were significantly higher in maturation stage enamel cells than in secretory stage cells. Our quantification of basal [Ca2+]i levels in enamel organ cells using Fura-2 showed ~135 nM of [Ca2+]i in secretory stage cells whereas in maturation stage cells levels were ~230 nM. To our knowledge this is the first study that quantitates Ca2+ levels in enamel cells. Differences in basal cytosolic Ca2+ between these cell types may be related to differences in cytosolic Ca2+ buffering, extrusion mechanisms, or a combination of these. This elevation during maturation may arise as the requirements for Ca2+ availability increase so that it can be more easily extruded.

Upon readdition of extracellular Ca2+ both cell types showed a significant increase in [Ca2+]i albeit this increase was markedly higher in maturation stage cells. Despite this marked increase during maturation and the known crystal growth expansion that also occurs at this stage, nucleation events leading to the formation of thin crystals in the secretory phase are still likely to require an active Ca2+ transport system. This growth requirement is in keeping with the increase in [Ca2+]i observed in secretory stage cells (Fig. 4). Despite these differences in Ca2+ dynamics between cell types, evidence that both showed Ca2+ release after thapsigargin stimulation followed by Ca2+ entry upon readdition of extracellular Ca2+ indicates that both have SOCE. Importantly, Ca2+ entry evoked in enamel cells from both stages treated with the specific CRAC channel blocker Synta-66 was significantly inhibited compared to control cells thus identifying CRAC channels as the SOCE type in enamel cells (Fig. 4). Given that ameloblasts form an epithelial barrier limiting the free flow of Ca2+, our data on the cellular localization of STIM1 and ORAI1 (Fig. 3B,D), together with our Fura-2 analysis using a pharmacological CRAC channel inhibitor, strongly suggest that CRAC channels are important mediators of Ca2+ entry into enamel cells. The identification of severely hypo-calcified enamel in patients with mutations in STIM1 and ORAI1 genes13,20,21 supports the functional role of CRAC channels in enamel development.

The CRAC channel inhibitor used here (Synta-66) significantly reduced Ca2+ influx into enamel cells although a small increase in [Ca2+]i was still detected (Fig. 4). This small Ca2+ increase might be linked to lack of efficient inhibition of this compound in the enamel cells, or it may alternatively indicate that other Ca2+ entry channels such as TRPC (putatively linked with SOCE channels38,39) are active in enamel cells. However our previous genome wide analysis surveying rat enamel organs did not identify the expression of TRPC channels in enamel cells using this methodological approach15, and no reports in the literature have thus far linked TRPC channels with abnormal enamel phenotypes.

Data shown here combined with previous studies identifying luminal ER Ca2+ buffering proteins2,3,22 indeed highlight the potential role for the ER in enamel cells as an essential component in Ca2+ transport enabling us to refine hypotheses concerning Ca2+ transport in enamel formation. In enamel biology, the calcium transcytosis hypothesis of Hubbard2,22,41 has gained recognition for several years. In this model, it is recognized that there is limited evidence for a paracellular route for Ca2+ movement in enamel epithelium. Instead, an active transport system is more likely5,6,7 through a transcellular route which requires three mechanistic steps: Ca2+ entry, transit and extrusion (reviewed in ref. 6). A classical Ca2+ transcellular model is the “calbindin-ferry” dogma where cytosolic Ca2+-binding proteins (calbindins) act as shuttles of Ca2+ across cells. However, the demonstration that calbindin28 kDa-null mice lack a dental phenotype40, together with biochemical data indicating that all three calbindins (calbindin 28 kDa, calbindin 9 kDa and calbindin 30 kDa) are not up-regulated during the maturation stage suggests that they are not essential in enamel formation41. In contrast, the extensive distribution of the ER in enamel cells, together with the localization of STIM1 and ORAI1 in rat maturation ameloblasts described here which enables multiple Ca2+ entry points, supports the role of ER as a key component for Ca2+ transport as previously proposed2,22. Support for this calcium transcytosis model comes from the studies on polarized pancreatic acinar cells where it has been shown that the ER functions as a lumenally continous compartment allowing the movement of Ca2+ from the base to the apex42,43. This might also be the case in ameloblasts but this hypothesis requires further testing.

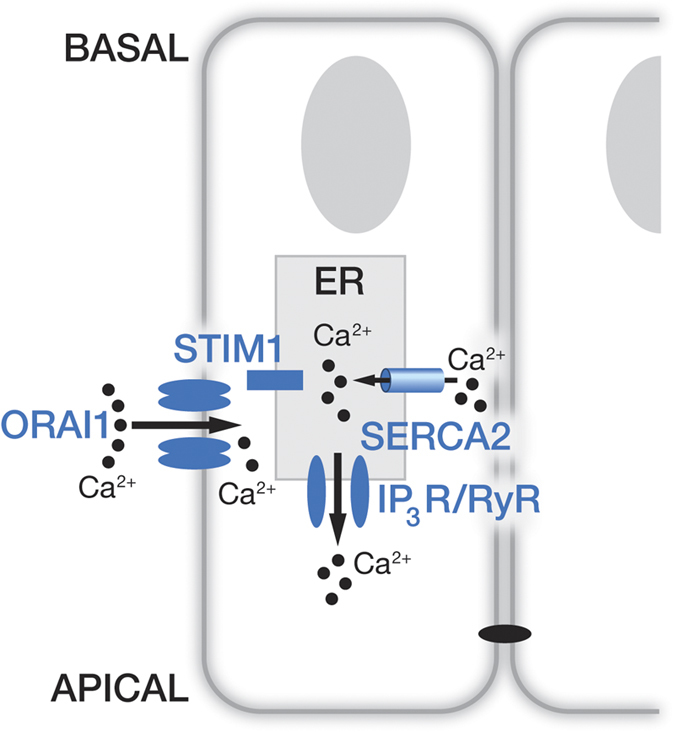

The data presented here allow us to propose a CRAC channel-regulated Ca2+ entry model in enamel cells as shown in Fig 5. Concerning the extrusion step, our recent data identifying the exchanger NCKX4 in enamel12 and reports on severe enamel pathologies found in patients and mouse models with NCKX4 deficiencies14, strongly suggests a key role for this exchanger in Ca2+ extrusion during enamel mineralization.

Figure 5. Schematic model representing calcium entry in enamel cells.

Working model for Ca2+ uptake by enamel cells showing maturation stage ameloblasts forming a cell barrier joined by tight junctions at the apical pole. In the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) we find that enamel cells express the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum SERCA2 as the main Ca2+ refilling pump. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R) and ryanodine receptors (RyR) are also identified as release channels with the former likely being the active release system. STIM1 has a wide distribution throughout the ER and ORAI1 is found in the plasma membrane of enamel cells. As Ca2+ pools are depleted in the ER, STIM1 clusters enable Ca2+ entry via the ORAI1 channel.

Our work provides the first functional evidence for Ca2+ uptake via CRAC channels in primary enamel cells. These data together with the localization of STIM1 and ORAI1 throughout the ameloblasts highlights the possibility that the ER may act as a key organelle enabling Ca2+ transport across the cells as held by the calcium transcytosis model. These data greatly advance our understanding of the mechanism regulating Ca2+ transport during enamel formation, and warrant further investigations into the role of SOCE in enamel cell signaling and calcium transport.

Methods

Tissue Dissections and Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR)

All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, and are in full compliance with Federal, State, and local laws and institutional regulations. Animals were maintained following NIH guidelines. Sprague Dawley rats or C57BL/6 mice were used as detailed below for each experiment. The use of rats was preferred over mice for the isolation and processing of enamel organ cells for Fura-2 AM analysis, RT-PCR and Western blot as previous studies had reported on anatomical landmarks in rats that allow us to independently isolate secretory from maturation stage enamel organs and because the larger size of rats makes this procedure easier44,45. In one instance, we used paraffin embedded mouse tissues for immunohistological analysis as the antibody had been widely used in mouse tissues but had not been tested in rats. This was the case for the ORAI1 antibody (see below). Rats and mice do not differ in the histological development of the enamel in any significant way. Rats (100–160 gram) were euthanized and their mandibles were immediately dissected out, then the surrounding soft tissues were removed. The bulk of the dissected enamel organ during the secretory stage is composed by ameloblasts but other adjacent cell types such as stratum intermedium cells may also be present. During maturation, papillary layer cells replace the stratum intermedium. Total RNA was extracted from rat secretory and maturation stage enamel organ cells and control tissues using RNeasyR Micro Kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Reverse-transcribed PCR was performed using iScripttm cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, USA). RT-PCR amplifications were set up in a total volume of 20 μl using 0.7 μg of cDNA, 250 nM forward and reverse primer using SsoAdvancedTM Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, USA). Cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 39 cycles of 95 °C for 10 sec, 58 °C for 30 sec. Specificity of PCR products was confirmed by analysis of a melting curve. RT-PCR amplification were performed on a CFX ConnectTM Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, USA) and all experiments were done in triplicate. The housekeeping gene beta-actin was amplified to standardize the amount of sample RNA. Relative quantification of gene expression was achieved using the ΔCT method. Primer sequences used can be found in the Supplemental Data section.

Immunostaining and Western blot

For immunohistochemical analysis, rats and mice at 10 days postnatal were euthanized. Isolated mandibles stripped of soft tissues were immersed in formalin overnight at 4 °C and decalcified in 4.13% EDTA (pH 7.3) for 7–10 days and washed. Appropriate positive control tissues were also collected and processed as for dental tissues but without the decalcification step. Samples were embedded in paraffin for sectioning (5 μm thick). After deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was performed by cooking the slides for 20 min in 10 mM citric buffer (pH 6.0) followed by blocking for 1 hr with Dako Diluent (Dako, USA). The following antibodies and dilutions were used: anti-STIM1 (1:200, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-calnexin (a marker for ER) (1:1000, Abcam), anti-ORAI1 (1:50, described in20) as well as anti-IP3R1 (1:50, Novusbio), anti-IP3R2 (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-IP3R3 (1:1000, Abcam), anti-SERCA2 (1:200, Abcam), anti-RyR1 (1: 500, LSBio), anti-RyR2 (1:200, Sigma-Aldrich) and anti-RyR3 (1:300, Abcam). Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Negative controls were provided by incubating sections with Dako Diluent lacking primary antibody. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated for 30 min at room temperature using appropriate secondary antibodies from Invitrogen at 1:800 (Anti Rabbit IgG AlexaFluor488 and/or Anti-Mouse IgG Alexa Fluor555). After washing, slides were mounted with a coverslip using Prolong Gold Mounting Media (Invitrogen, USA) containing DAPI. Images were obtained using a Leica TCS SP5 II confocal microscope or a Nikon Eclipse 2000TE. The immunolocalization of Stim2 was performed by incubating with an anti-Stim2 antibody (1:50, Sigma-Aldrich) using Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories) and counterstaining with haematoxylin before mounting the slides with Vecta Mount Mounting Media (Vector Laboratories). Samples were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope with NIS Elements BR3.2 (Nikon) software. Western blot analysis of SERCA2 was performed as described45 using the following antibodies: SERCA2 (1:1000, Abcam), and actin (1:2000, Santa Cruz).

Cell Isolation

Rats (100–160 gram) were euthanized, mandibles were dissected out and the surrounding soft tissues removed. Isolated mandibles were transferred to Hanks solution (GIBCO) containing 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic and kept on ice at all times. Isolated SSEO and MSEO cells were treated with 0.15% collagenase (Roche, Tokyo, Japan) in PBS for 1 hr at 37 °C in a 5%-CO2 incubator followed by Trypsin/EDTA (Gibco, Life Technologies, USA) for 10 min at 37 °C in a 5%-CO2 incubator and manual disruption. Reaction was stopped by adding DMEM (Gibco by Life Technologies, USA) containing 30% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% glutamine. For intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) measurement, isolated SSEO and MSEO cells were cultured in X-VivoTM 15 (Lonza, USA) cell media containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% glutamine and maintained at 37 °C in a 5%-CO2 incubator. Cells were used within 24 hrs after isolation.

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Secretory stage enamel organ (SSEO) cells and maturation stage enamel organ (MSEO) cells were kept in media for 4 hrs at 37 °C in a 5%-CO2 incubator. To determine intracellular Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i), cells were loaded with Fura-2-AM (5 μM, Life Technology Invitrogen, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed with X-VivoTM 15 cell media containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1% glutamine. Finally, cells were dispensed into 96-well black clear bottom plates. Fura-2 emission was detected at 510 nm after excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm using a FlexStation3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA)46. The ratio (R) of Fura-2 emission following excitation at 340 nm (F340) and 380 nm (F380) were calculated for each time point. [Ca2+]i was estimated from calibration curves by using the Calcium Calibration Buffer Kit#1 (Molecular Probes, Life technologies, USA) using the following equation: [Ca2+]i = Kd x ((R-Rmin)/(Rmax-R)) x (F380max/ F380min) as described by Grynkyewicz46. Kd is the dissociation constant of Fura-2 (Kd = 156 nM); R is the ratio of Fura-2 emission following excitation at 340 nm divided by the Fura-2 emission following excitation at 380 nm; Rmin was measured in nominally Ca2+ free buffer; Rmax was measured at saturating Ca2+ concentration (39 μM); F380max is the fluorescence intensity after excitation at 380 nm in Ca2+ free buffer; F380min is the fluorescence intensity at saturating Ca2+ concentration (39 μM). All experiments were performed at 25 °C. In order to measure SOCE, intracellular Ca2+ stores were depleted by inhibiting SERCA activity with thapsigargin (1.25 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in cells kept in Ca2+ free Ringer solution followed by readdition of an equal volume of Ca2+-containing Ringer solution at the times indicated to a final concentration of 2 mM Ca2+. For some experiments, SSEO and MSEO stage cells were treated with the CRAC channel inhibitor Synta compound 66 (Synta-66, 3 μM)31 for 30 min before initiating the experiment and then Synta-66 was added to all the solutions used during the experiment. Buffer solutions contained (in mMol/l): 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 32.2 Hepes, 2 Na2HPO4, 4 CaCl2, and 5 glucose at pH 7.4 (extracellular Ca2+ buffer) or 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 2 Na2HPO4, 32.2 Hepes, 0.5 EGTA, 5 glucose, pH 7.4 (Ca2+-free buffer). Ca2+ data were acquired using SoftMax Pro software (Molecular Device, USA) and analyzed using GraphPad Prism v.5. Cells were analyzed for baseline [Ca2+]i, increase in [Ca2+]i after ER depletion and SOCE. The area under the curve (A.U.C.) following Ca2+ influx was analyzed using GraphPad Prism v.5.

Statistics

Data are provided as mean ± SEM, n represents the number of independent experiments. Differences were tested for significance using Student’s unpaired two-tailed t-test or ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Nurbaeva, M. K. et al. Dental enamel cells express functional SOCE channels. Sci. Rep. 5, 15803; doi: 10.1038/srep15803 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH/NIDCR K99/R00 award (DE022799) to RSL, NIH grant AI097302 to SF, NIH/NIDCR (DE019629) to MLP, NIH grant AI083432 to YG, and by the Melbourne Research Unit for Facial Disorders to MJH. ARC is funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Alfonso Martin Escudero Foundation. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments which helped improve this manuscript. Finally, the authors would like to thank Johanna Warshaw for help with Figure 5.

Footnotes

SF is a scientific co-founder of Calcimedica Inc. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Designed experiments (M.K.N., R.S.L., M.E., S.S., Y.G., S.F. and M.H.), performed experiments (M.K.N., M.E., S.S. and RSL), analyzed data (M.K.N., R.S.L., M.E., S.F., A.R.C., M.H., C.E.S., S.S., M.L.P. and Y.G.), wrote the paper (M.K.N., R.S.L., S.F., M.H., A.R.C., M.E., C.E.S., S.S., M.L.P and Y.G.).

References

- Smith C. E. Cellular and chemical events during enamel maturation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 9, 128–161 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard M. J. Calcium transport across the dental enamel epithelium. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 11, 437–466 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard M. J., McHugh N. J. & Carne D. L. Isolation of ERp29, a novel endoplasmic reticulum protein, from rat enamel cells. Evidence for a unique role in secretory-protein synthesis. Eur J Biochem. 267, 1945–1957 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard M. J. Rapid purification and direct microassay of calbindin9kDa utilizing its solubility in perchloric acid. Biochem J. 293(Pt 1), 223–227 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdal A., Hotton D., Pike J. W., Mathieu H. & Dupret J. M. Cell- and stage-specific expression of vitamin D receptor and calbindin genes in rat incisor: regulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Dev Biol. 155, 172–179 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard M. J. Calbindin28kDa and calmodulin are hyperabundant in rat dental enamel cells. Identification of the protein phosphatase calcineurin as a principal calmodulin target and of a secretion-related role for calbindin28kDa. Eur J Biochem. 230, 68–79 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin I. K., Winz R. A. & Hubbard M. J. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump is up-regulated in calcium-transporting dental enamel cells: a non-housekeeping role for SERCA2b. Biochem J. 358, 217–224 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borke J. L. et al. Expression of plasma membrane Ca++ pump epitopes parallels the progression of enamel and dentin mineralization in rat incisor. J Histochem Cytochem. 41, 175–181 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mornstad H. Calcium-stimulated ATPase activity in homogenates of the secretory enamel organ in the rat. Scand J Dent Res. 86, 1–11 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama A. H., Zaki A. E. & Eisenmann D. R. Cytochemical localization of Ca2+-Mg2+ adenosine triphosphatase in rat incisor ameloblasts during enamel secretion and maturation. J Histochem Cytochem. 35, 471–482 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura R. et al. Sodium-calcium exchangers in rat ameloblasts. J Pharmacol Sci. 112, 223–230 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P. et al. Expression of the sodium/calcium/potassium exchanger, NCKX4, in ameloblasts. Cells Tissues Organs. 196, 501–509 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. et al. STIM1 and SLC24A4 Are Critical for Enamel Maturation. J Dent Res. 93, 94S–100S (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry D. A. et al. Identification of mutations in SLC24A4, encoding a potassium-dependent sodium/calcium exchanger, as a cause of amelogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet. 92, 307–312 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacruz R. S. et al. Identification of novel candidate genes involved in mineralization of dental enamel by genome-wide transcript profiling. J Cell Physiol. 227, 2264–2275 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth S. & Gwack Y. Orai1, STIM1, and their associating partners. J Physiol. 590, 4169–4177 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J. W. Capacitative calcium entry: from concept to molecules. Immunol Rev. 231, 10–22 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik R. M., Wang B., Prakriya M., Wu M. M. & Lewis R. S. Oligomerization of STIM1 couples ER calcium depletion to CRAC channel activation. Nature. 454, 538–542 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S. Ca(2+) influx in T cells: how many Ca(2+) channels? Front Immunol. 4, 99 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarl C. A. et al. ORAI1 deficiency and lack of store-operated Ca2+ entry cause immunodeficiency, myopathy, and ectodermal dysplasia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 124, 1311–1318 e1317 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S. et al. Antiviral and regulatory T cell immunity in a patient with stromal interaction molecule 1 deficiency. J Immunol. 188, 1523–1533 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard M. J. Abundant calcium homeostasis machinery in rat dental enamel cells. Up-regulation of calcium store proteins during enamel mineralization implicates the endoplasmic reticulum in calcium transcytosis. Eur J Biochem. 239, 611–623 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano Y. Enamel mineralization and the role of ameloblasts in calcium transport. Connect Tissue Res. 33, 127–137 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer J. P. & Fincham A. G. Molecular mechanisms of dental enamel formation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 6, 84–108 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopulos P. B. et al. Themes and variations in ER/SR calcium release channels: structure and function. Physiology (Bethesda). 27, 331–342 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme K., Domingue O., Guillemette B. I. & Guillemette G. Immunohistochemical localization of type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor to the nucleus of different mammalian cells. J Cell Biochem. 85, 219–228 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecaetsbeek I., Vangheluwe P., Raeymaekers L., Wuytack F. & Vanoevelen J. The Ca2+ pumps of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3, 1–24 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemura H., Hughes A. R., Thastrup O. & Putney J. W. Jr. Activation of calcium entry by the tumor promoter thapsigargin in parotid acinar cells. Evidence that an intracellular calcium pool and not an inositol phosphate regulates calcium fluxes at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 264, 12266–12271 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S. et al. Fundamental Ca2+ signaling mechanisms in mouse dendritic cells: CRAC is the major Ca2+ entry pathway. J Immunol. 166, 6126–6133 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifach A. & Lewis R. S. Mitogen-regulated Ca2+ current of T lymphocytes is activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90, 6295–6299 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Sabatino A. et al. Targeting gut T cell Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels inhibits T cell cytokine production and T-box transcription factor T-bet in inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol. 183, 3454–3462 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fill M. & Copello J. A. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol Rev. 82, 893–922 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule D. I., Ernst S. A., Ohnishi H. & Wojcikiewicz R. J. Evidence that zymogen granules are not a physiologically relevant calcium pool. Defining the distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 272, 9093–9098 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echevarria W., Leite M. F., Guerra M. T., Zipfel W. R. & Nathanson M. H. Regulation of calcium signals in the nucleus by a nucleoplasmic reticulum. Nat Cell Biol. 5, 440–446 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T., Goldberg M., Takuma S. & Garant P. R. Cell biology of tooth enamel formation. Functional electron microscopic monographs. Monogr Oral Sci. 14, 1–199 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard M. J. & McHugh N. J. Mitochondrial ATP synthase F1-β-subunit is a calcium-binding protein. FEBS Letters. 391, 323–329 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermassen E., Parys J. B. & Mauger J. P. Subcellular distribution of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors: functional relevance and molecular determinants. Biol Cell. 96, 3–17 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. S. Store-operated calcium channels: new perspectives on mechanism and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3, 1–24 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj S., Sun Y. & Singh B. B. TRPC channels and their implication in neurological diseases. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 9, 94–104 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull C. I. et al. Calbindin independence of calcium transport in developing teeth contradicts the calcium ferry dogma. J Biol Chem. 279, 55850–55854 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard M. J., McHugh N. J. & Mangum J. E. Exclusion of all three calbindins from a calcium-ferry role in rat enamel cells. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 119, 112–119 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogami H., Nakano K., Tepikin A. V. & Petersen O. H. Ca2+ flow via tunnels in polarized cells: recharging of apical Ca2+ stores by focal Ca2+ entry through basal membrane patch. Cell. 88, 49–55 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. K., Petersen O. H. & Tepikin A. V. The endoplasmic reticulum as one continuous Ca(2+) pool: visualization of rapid Ca(2+) movements and equilibration. EMBO J. 19, 5729–5739 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanci A. et al. Comparative immunochemical analyses of the developmental expression and distribution of ameloblastin and amelogenin in rat incisors. J Histochem Cytochem. 46, 911–934 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacruz R. S. et al. Adaptor protein complex 2-mediated, clathrin-dependent endocytosis, and related gene activities, are a prominent feature during maturation stage amelogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 28, 672–687 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. et al. Ratiometric Ca+2 measurement in human recombinant muscarinic receptor subtypes using the Flexstation scanning fluorometer. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 29, 100–106 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.