Abstract

Virtually no longitudinal research has examined psychological characteristics or events that may lead to adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI). This study tested a cognitive vulnerability-stress model as a predictor of NSSI trajectories. Clinically-referred adolescents (n =143; 72% girls) completed measures of NSSI, depression, attributional style, and interpersonal stressors during baseline hospitalization. Levels of NSSI were reassessed 3, 6, 9, 15, and 18 months later. Latent growth curve analyses suggested that a cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction significantly predicted increases in NSSI between 9 and 18 months post-baseline. This association remained significant while considering the longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and NSSI; results were not significantly mediated by depressive symptoms at 9 months.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to a broad class of behaviors defined by direct, deliberate, and socially unacceptable damage to one’s body tissue without suicidal intent. Once considered a behavior restricted to individuals with developmental disabilities or with borderline personality disorder (BPD), NSSI now is recognized as a widespread and pervasive public health problem, occurring at significant rates within community-based samples of adults (1–4%; Briere & Gil, 1998; Klonsky, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2003), preadolescents (7%; Hilt, Nock, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2008), and adolescents (12–15%; Favazza, DeRosear, & Conterio, 1989; Ross & Heath, 2002). Prevalence estimates from clinical samples are notably higher overall and reveal a similar developmental pattern; rates of NSSI are 2 to 3 times higher among adolescents (40–60%; Darche, 1990; DiClemente, Ponton, & Hartley, 1991) compared to adults (~21%; Briere & Gil, 1998). Some studies have reported that adolescent girls engage in NSSI more frequently than boys (Bhugra, Thompson, Singh, & Fellow-Smith, 2003; Ross & Heath, 2002). The evidence is conflicting, however, as other investigators have failed to find gender differences (e.g., DiClemente et al., 1991; Garrison et al., 1993; Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer, 2002; Hilt, Nock, et al., 2008).

Despite the striking prevalence of NSSI, as well as some suggestion that its incidence is increasing (Hawton, Fagg, Simkin, Bale, & Bond, 1997), NSSI research is still in its nascent stages of development and has been characterized by three major limitations. First, much of the extant literature has provided merely descriptive data regarding its phenomenology and psychosocial correlates. Although several theoretical models have been proposed to organize clinical descriptions and guide inquiry (e.g., Favazza, 1998; Suyemoto, 1998; Yip, 2005), there is a paucity of research that has either rigorously evaluated theory-based hypotheses or used advanced research or analytic methods. Instead, much of the evidence to date has come from uncontrolled case studies and correlational research or has relied on self-reported measures and cross-sectional methodology (Prinstein, Guerry, Browne, & Rancourt, 2009). Second, no studies have been conducted to examine NSSI using prospective, longitudinal designs. This is a central failing: Without establishing its temporal aspects, the causes, correlates, and consequences of NSSI cannot be differentiated.

Third, studies of NSSI most often involve adults or convenience samples of college-aged students. This is despite the salient research relevance of adolescence, both as the age group during which rates of NSSI are the highest and as the developmental period most associated with the initiation of these behaviors (Favazza & Conterio, 1988). Although such work with adults has yielded essential contributions to the literature, its focus has precluded the empirical examination of NSSI through a developmental psychopathology perspective. Thus, progress toward identifying distal, developmental risk factors for NSSI has been limited. There is a pressing need for prospective, longitudinal research that specifically targets the development of NSSI during the critical period of adolescence. Utilizing a clinically referred sample would constitute a logical and efficient beginning for this line of research.

To begin to conceptualize and understand NSSI using a developmental psychopathology framework requires a dual emphasis on both proximal and distal risk factors. On the one hand, the examination of proximal factors—those immediately antecedent to the engagement in NSSI—may have particular implications for the development of treatments aimed at identifying imminent warning signs and redirecting NSSI impulses. On the other hand, research into distal factors related to NSSI is essential for illuminating such aspects as longitudinal trajectories of NSSI and certain characteristics that may predispose youths for later, NSSI-precipitating conditions. These will inform attempts to prevent or ameliorate the syndrome.

Past work examining proximal factors has highlighted the usefulness of functional models of NSSI to help understand the immediate “triggers” or reinforcers of these behaviors. By far, most evidence to date has suggested that individuals engage in NSSI as a strategy to alleviate acute emotional distress or more general negative affect (i.e., an automatic negative reinforcement function; Brown, Comtois, & Linehan, 2002; Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006; Klonsky, 2007; Nock & Prinstein, 2004; Suyemoto, 1998; Yip, 2005). In addition to the substantial empirical evidence that has accumulated to support this theory more generally (e.g., Haines, Williams, Brain, & Wilson, 1995), recent research has begun to elucidate the nature of this proximal association between intensely negative affective states and NSSI. Most critically, it has been shown that self-injuring adolescents, as compared to those without such histories, tend to exhibit higher levels of physiological reactivity in response to stress, a reduced ability to tolerate stress, and concurrent deficits in social problem-solving abilities (Nock & Mendes, 2008).

However, given the absence of prior longitudinal research on NSSI and the resulting paucity of data related to distal risk factors, the extant literature scarcely has begun either to elucidate factors that may be associated with these heightened stress reactions or to test them as distal risk factors for later NSSI. In other words, examination of factors that promote affect dysregulation and social-cognitive deficits may yield important information about risks that are theoretically and temporally “upstream” from immediate NSSI precipitants. This avenue of investigation is likely crucial for the development and testing of prevention and early intervention strategies for NSSI. Specifically, it will be important to examine what factors may be associated with maladaptive stress reactions. The current study examined social-cognitive responses to stressful events as one potential factor.

Our hypothesis that distal risk factors for NSSI involve social-cognitive defects in the interpretations of stressors has a parallel in depression research. Briefly, cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression specify that some individuals demonstrate a vulnerability to negative affect through a pattern of making internal (as opposed to external), stable (as opposed to transient), and global (as opposed to specific) attributions following negative life events (e.g., Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). These models have received much theoretical and empirical attention, generally providing support for the longitudinal association between the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction and future depressive symptoms in adult populations (see Abramson et al., 2002; Ingram, Miranda, & Segal, 1998; Scher, Ingram, & Segal, 2005, for reviews), as well as among samples of children and adolescents (e.g., Hilsman & Garber, 1995; Lewinsohn, Joiner, & Rohde, 2001; see Lakdawalla, Hankin, & Mermelstein, 2007, for a review).

The present study examined a cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction as a distal risk factor for adolescent NSSI. Prior theory and preliminary, retrospective research suggests that interpersonal stressors may be especially relevant to NSSI. For example, Cochrane and Robertson (1975) demonstrated that, as compared to non-self-injuring controls, self-injurers tend to experience far more unpleasant, stressful events in the year preceding incidents of NSSI. These events commonly included a number of interpersonal stressors (e.g., “increases in the number of arguments with family members,” “breakup with steady boy or girlfriend”; see also Hilt, Cha, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008). Moreover, interpersonal stress may be especially potent for adolescents. Corresponding to the increasing prominence of the peer group and an expanding social network, adolescents tend to experience both a higher number of interpersonal stressors and report greater emotional reactivity to them, as compared to children (Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994; Larson & Ham, 1993; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999). These findings may at least partially account for the observed developmental variation in the prevalence of NSSI.

This study examined the longitudinal effects of cognitive vulnerability combined with the experience of interpersonal stressors on trajectories of NSSI within a clinically-referred adolescent sample. We predicted that an interaction between high levels of a negative attributional style and the occurrence of stressful, interpersonally-themed life events would be associated with increases in incidents of NSSI across an 18-month interval. It was anticipated that cognitive vulnerability-stress may be related to NSSI through one of two pathways. First, given past research on the importance of this cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction on depressive symptoms and the concurrent association between depressive symptoms and NSSI (Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006), we examined whether depressive symptoms might mediate the longitudinal association between this interaction and NSSI. Second, we also considered an unmediated pathway between cognitive vulnerability-stress and NSSI. This model was based on the possibility that, in addition to its effects on depressed affect, the interaction of cognitive vulnerability and stress also may contribute to more general arousal and/or highlight a tendency for low frustration tolerance, or poor social-cognitive skills in the context of stress more broadly. Thus, an unmediated pathway would suggest multifinality of the interaction between cognitive vulnerability and stress on multiple outcomes, including NSSI (in addition to depressive affect). Examining the role of cognitive vulnerability-stress on NSSI beyond the potential mediating effects of depression also offers a stringent test of cognitive vulnerability-stress as a specific, unique predictor of NSSI that is not accounted for merely by interrelations with depressive symptoms.

Thus, this study offers an important preliminary step toward understanding how stress response patterns may be distal contributors to NSSI. If supported, this previously untested hypothesis would provide a useful theoretical foundation for a novel line of empirical investigation, as well as help to understand developmental vulnerabilities for the aversive negative states that may serve as immediate precipitants to self-injurious behaviors. In addition, as the present study constitutes the first prospective, longitudinal examination of NSSI, descriptive information was gathered that is relevant to the course of NSSI across an 18-month follow-up period.

METHODS

Participants

Participants included 143 adolescents (72% girls) between the ages of 12 and 15 years (M =13.51, SD =.75) and in Grades 7 (20%), 8 (40%) or 9 (40%) at baseline. Approximately 75% of participants were White/Caucasian, 4% Latino American, 3% African American, and 17% Mixed Ethnicity. Approximately 27% of adolescents lived with both biological parents, 29% with their biological mother only, and 15% with their biological mother and a step-parent. The remaining 29% of adolescents lived with their biological father, extended family members, or in foster or other temporary care. Nineteen percent of mothers reported that they had not obtained a high school diploma, 40% of mothers’ highest education was a high school degree, 14% had earned a trade degree, 11% attended some undergraduate college, and 9% had obtained a college degree or higher.

All participants were recruited from a psychiatric inpatient facility, and all study procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Brown University Medical School. During the period of recruitment, 246 adolescents matching study inclusion (12–15 years old; no past or current psychosis or mental retardation) were admitted to the inpatient unit. At the time of data collection, approximately 40% of all admissions onto this unit were discharged or transferred within 1 to 2 days of admission. This length of stay was associated with a variety of factors (e.g., limitations proscribed by insurance carriers, vacancies at local facilities) and was not related to the severity of adolescents’ psychological symptoms or adolescents’ socioeconomic status.

Consistent with human subjects regulations, adolescent patients and their parents were approached for study participation only after clinic personnel had gained permission from adolescents’ parents/guardians to be contacted about this investigation (typically on the 2nd day following admission). Parental consent and adolescent assent for study participation was subsequently requested from the families of 183 of these eligible adolescents, and 162 (88.5%) ultimately provided consent/assent. Of these, 143 (88.3%) were available to be assessed on study measures (19 participants were discharged after consenting but before data could be collected). Adolescents and their parents initially were assessed during hospitalization (baseline) immediately following consent, typically within 2 to 4 days of admission. Adolescents and parents also completed follow-up assessments at 3, 6, 9, 15, and 18 months post-baseline. The psychiatric status of participants at baseline, as assessed by the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-Adolescent Report; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), included major depressive disorder (33.6%), oppositional defiant disorder (27.6%), conduct disorder (18.7%), posttraumatic stress disorder (14.2%), social phobia (13.4%), and generalized anxiety disorder (6.7%; cumulative percentages exceeded 100% because of comorbidities).

Data were missing for two reasons common to research of this type. First, certain logistical challenges inherent to inpatient data collection (e.g., competing demands for patients’ time, unexpected discharge or transfer) yielded missing data on some items or measures within participants. Second, some data were missing because of attrition over various longitudinal intervals (e.g., family relocation, study dropout, etc.). Many retention strategies were utilized, including frequent phone and mail contact with participants and their network of immediate and extended family members and friends, searches within public access databases for current contact information, and provision of incentives to participants to encourage completion of follow-up assessments (i.e., $30 at each follow-up time point for each adolescent and parent participant).

Of the 143 adolescents who completed baseline assessments, 133 (93%) participated in at least one of the follow-up time points, 115 (80%) participated in at least two follow-ups, 106 (74%) participated in at least three, 96 (67%) in four, and 76 (53%) completed every follow-up assessment. A total of 102 adolescents (71%) participated at the final assessment. This retention rate is comparable to prior research on similar populations (e.g., Boergers & Spirito, 2003). Analyses were conducted to compare adolescents with and without complete longitudinal data on all baseline study variables. Analyses also were conducted to examine adolescents who did and did not participate in the final assessment. In both cases, no significant differences were revealed on any study variables, suggesting no evidence for attrition biases. Missing data analyses indicated that data were missing at random, Little’s MCAR χ2(1840) =1839.57, ns. To prevent the unnecessary omission of valuable data (e.g., listwise deletion), all analyses were conducted using all available data. Analyses using only available data revealed an identical pattern of results.

Measures

All adolescent questionnaire-based measures were read aloud by a trained research assistant during individual meetings while adolescents privately recorded their responses. This procedure allowed for adequate probing and clarification of study items when necessary, careful monitoring of adolescents’ attention and conscientiousness while completing measures, and immediate checking for inconsistencies or omissions in responses.

NSSI

NSSI was assessed at baseline and at each follow-up time point using a set of five items adapted from the Suicide Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ; Reynolds, 1985). These items reported the frequency that adolescents engaged in several types of NSSI (i.e., cut/carved skin, hit self on purpose, pulled hair out, burned skin, or other method) without suicidal intent. Respondents were asked to consider the time frame of the past year in answering these items at the first administration of the questionnaire (“baseline”), and then for each subsequent time point (i.e., at the 3-, 6-, 9-, 15-, and 18-month follow-up assessments) they were asked to report on the previous 3 months. The frequency of engagement in each item was reported on a 5-point scale ranging 1 (never) to 5 (almost every day). A mean score across all five items was computed at baseline (α =.70).

Attributional style

Adolescents’ attributional style was assessed at baseline using the revised Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire (CASQ-R; Kaslow & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). The CASQ-R is a 24-item, forced-choice questionnaire that describes 12 positive and 12 negative hypothetical events. Participants are instructed to imagine each event happening to them and then decide which of the two provided explanations best describes the cause of the event. For example, the item “You get a bad grade in school” lists the following two explanations: “1) I am not a good student” or “2) Teachers give hard tests.” Throughout the CASQ-R for a given item, two of the dimensions of attributional style (i.e., internal/external, stable/unstable, global/ specific) are held constant, whereas the third is varied. In the example, the locus dimension is varied (internal vs. external), whereas the stability and globility dimensions are held constant.

Composite scores for each of the Positive and Negative Events subscales are calculated by adding together the internal, stable, and global scores across each respective category of items. The overall composite score for the CASQ-R, which is the index utilized in the present study, is derived by subtracting the composite negative event score from the composite positive event score. Scores on this scale range from −12 to +12, with lower scores indicating a more negative attributional style. The psychometric properties of the CASQ-R have shown moderate internal consistency for the overall composite score and fair test–retest reliability (Thompson, Kaslow, Weiss, & Nolen Hoeksema, 1998). In this sample, the coefficient alpha was found to be .74, which is consistent with the value found by Thompson and colleagues (1998; α =0.61).

Interpersonal life events

Adolescents’ experience of life stressors were assessed at baseline using a modified version of the Life Events Checklist (LE-C). The LE-C is a 30-item measure based on several life event inventories developed for use with adolescents (see Coddington, 1972; Compas, Davis, Forsythe, & Wagner, 1987; Johnson & McCutcheon, 1980; Masten, Garmezy, Tellegen, Pellegrini, & Larkin, 1988). Participants were asked whether each of 30 potentially negative life events had happened to them or their families in the past 9 months. Salient points in time such as holidays and school calendar events were discussed with each adolescent to provide referents for the time interval in question. Because of the previously noted relevance of interpersonally-themed stressors among adolescents, only those items on the LE-C that could be explicitly categorized as stressful interpersonal life events were included in the foregoing analyses (e.g., “You and your boyfriend/girlfriend had a big fight or broke up”). Adolescents’ scores across this interpersonal domain of 10 items were summed to create an index of interpersonal life stress. Because the scale is a checklist of independent items, it is not appropriate to calculate its internal consistency.

Depression

Adolescents completed the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) at baseline and again at 9 months post-baseline. The CDI, which is a modification of the Beck Depression Inventory designed for use with preadolescent children, consists of 27 items that assess cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms of depression, including all but one (psychomotor agitation) of the DSM–IV criteria for a major depressive episode. For each item, children choose among three statements that best describe their level of depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks. Item choices are assigned a numerical value from 0 to 2, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of depression. A mean score was computed across all items with one exception (i.e., suicidal ideation) to minimize overlap between constructs. The CDI is a widely used self-reported measure of depressive symptoms in children, and has reasonably high levels of internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent validity with other self-reported measures (Carey, Faulstich, Gresham, Ruggiero, & Enyart, 1987; Kazdin, French, Unis, & Esveldt-Dawson, 1983; Saylor, Finch, Baskin, Furey, & Kelly, 1984; Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, 1984). The CDI can be used with youths between the ages of 7 and 18 years (Kazdin, 1990). Internal consistency in the present sample was .88.

Data Analyses

Three sets of analyses were conducted to examine study hypotheses. First, descriptive statistics were conducted to examine the means and standard deviations on all study variables over the 18-month longitudinal period. Correlational analyses also were performed between all study variables. Second, to better understand the course of NSSI over the 18-month follow-up period, an unconditional growth curve model using latent curve analysis was examined. The use of latent curves allows for an estimation of the slope and pattern of growth within the entire sample, as well as predictors of individual temporal growth trajectories (Bollen & Curran, 2006). All latent curve analyses were performed using AMOS 16.0.

It was anticipated that NSSI slopes may be nonlinear, given that for many adolescents NSSI may occur at a high incidence at baseline (i.e., during hospitalization), decrease following discharge, and possibly increase again over the extended longitudinal period. An initial model examined a single latent slope factor. The six measures of NSSI (at baseline, 3, 6, 9, 15, and 18 months post-baseline) were included as observed indicators, with latent intercept and slope factors estimated. A latent intercept factor with paths to all observed indicators set to 1 was modeled. Path weights between the latent slope factor and each observed indicator of NSSI were set to 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6, respectively.

The single slope model then was compared to alternative models examining (a) a piecewise approach (i.e., linear spline), or (b) a curvilinear slope function. The use of the piecewise approach allowed for an examination of two separate slope functions (Bollen & Curran, 2006). Because growth curve modeling requires at least three time points to compute a slope, the six time points were divided for analyses as follows: a first slope function modeled the curve between baseline, 3, and 6 months post-baseline, whereas the second slope function modeled the curve between 9, 15, and 18 months post-baseline. Each linear spline was modeled with two paths fixed (to 0 and 1, respectively) and the third path allowed to freely vary. The curvilinear model required the inclusion of an initial slope function (with paths to observed indicators set to indicate the three month intervals: 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, respectively), and a second slope function with each corresponding path weight squared (Bollen & Curran, 2006).

The best fitting model of those analyses just presented was built upon to examine the central study hypotheses related to the prospective prediction of NSSI. Hypotheses tested a conditional growth curve model. Paths were estimated between exogenous predictors and the latent intercept and slope factors. The following predictors were included: attributional style (CASQ-R); stressful interpersonal life events (LE-C); and the interaction of life events with attributional style. In addition, depressive symptoms (CDI), as measured at baseline was included in the model as an exogenous predictor to ensure that other variables were not simply serving as a proxy for depression. All predictors were allowed to covary. Finally, depressive symptoms measured at 9 months post-baseline also was entered into the model to test (a) whether depressive symptoms would likewise be predicted by the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction at baseline and (b) whether depressive symptoms served as a mediator of this interaction’s prediction of NSSI between 9 and 18 months.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for all study variables, as well as the results of t tests examining gender differences. Additional statistics were computed to examine the number of adolescents who reported NSSI at each time point. Results indicated that more than two thirds of the full sample (95 adolescents) reported that they had engaged in some form of NSSI during the year prior to hospitalization. At all time points subsequent to the baseline assessment, however, the numbers of individuals reporting such behaviors over each preceding 3-month period were markedly decreased from baseline (all ps < .001). These numbers remained relatively stable across the extended follow-up period, ranging from 23 adolescents (22.8% of the follow-up sample) reporting any form of NSSI at 15 months postbaseline to 34 individuals (34% of the follow-up sample) at 9 months post-baseline. As with the number of self-injurers, the overall frequency of NSSI declined considerably following hospital discharge and remained relatively low across the 18-month follow-up period.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Primary Study Variables and Tests for Gender Differences

| Total | Boys | Girls | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSI (N (%) Reporting Any Behavior) | ||||

| Baselinea (n =140) | 95 (67.9%) | 19 (48.7%) | 76 (75.2%) | χ2(1) =9.08** |

| 3 Months (n =101) | 33 (32.7%) | 8 (24.2%) | 25 (36.8%) | χ2(1) =1.58, ns |

| 6 Months (n =107) | 31 (29.0%) | 4 (12.1%) | 27 (36.5%) | χ2(1) =6.58* |

| 9 Months (n =100) | 34 (34.0%) | 6 (20.0%) | 28 (40.0%) | χ2(1) =3.74, ns |

| 15 Months (n =101) | 23 (22.8%) | 3 (10.3%) | 20 (27.8%) | χ2(1) =3.57, ns |

| 18 Months (n =102) | 29 (28.4%) | 5 (16.7%) | 24 (33.3%) | χ2(1) =2.89, ns |

| NSSI (Composite Mean, M, SD) | ||||

| Baselinea (n =140) | 1.54 (.62) | 1.36 (.57) | 1.61 (.63) | t(138) =−2.19* |

| 3 Months (n =101) | 1.21 (.41) | 1.17 (.39) | 1.23 (.42) | t(99) =−.72 |

| 6 Months (n =107) | 1.16 (.34) | 1.03 (.09) | 1.21 (.40) | t(87.69)b=−3.77*** |

| 9 Months (n =100) | 1.19 (.39) | 1.11 (.30) | 1.22 (.42) | t(98) =−1.33 |

| 15 Months (n =101) | 1.08 (.20) | 1.02 (.06) | 1.11 (.23) | t(91.09)b =−2.95** |

| 18 Months (n =102) | 1.18 (.42) | 1.10 (.27) | 1.21 (.48) | t(100) =−1.16 |

| CASQ–R (M, SD) | ||||

| Baseline (n =132) | 2.86 (4.27) | 3.70 (4.18) | 2.54 (4.28) | t(130) =1.41 |

| Life eventsc,d (M, SD) | ||||

| Interpersonal (n =109) | .34 (.17) | .29 (.17) | .37 (.17) | t(107) =−2.19* |

| Depression (CDI; M, SD) | ||||

| Baseline (n =144) | .72 (.36) | .63 (.37) | .76 (.35) | t(142) =−2.01* |

| 9 Months (n =100) | .47 (.29) | .32 (.15) | .53 (.31) | t(96.10)b =−4.50*** |

Note: NSSI =Nonsuicidal self-injury; CASQ-R =Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire – Revised; CDI =Child Depression Inventory.

Past year.

Equal variances not assumed.

Measured at baseline.

Past 9 months.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Gender differences were observed consistently across all longitudinal measures of NSSI. At baseline hospitalization, a significantly greater proportion of adolescent girls reported that they had engaged in some form of NSSI over the previous year than did boys (48.7% vs. 75.2%), χ2(1) =9.08, p < .01. Although a higher proportion of girls engaged in NSSI at every follow-up time point, this difference only reached statistical significance at 6-month follow-up (12.1% vs. 36.5%), χ2(1) =6.58, p < .05. Similarly, a trend was found whereby adolescent girls reportedly engaged in NSSI more frequently than did boys at all six time points. However, this pattern of gender differences in favor of girls only reached statistical significance at baseline, 6 months, and 15 months post-baseline (all ps < .05, ds =.40, .53, .45, respectively).

In general, results from descriptive analyses for the remaining study variables were in line with expectations and consistent with past work. Girls reported a significantly greater number of interpersonal stressors (M =.37, SD =.17) than did boys (M =.29, SD =.17) over the 9-month period preceding hospitalization, t(107) =−2.19, p < .05, d =.47. Girls also reported significantly higher symptoms of depression at both baseline, t(142) =−2.01, p < .05, d =.36, and 18-month follow-up, t(88.38) =−4.24, p < .001, d =.72. Intercorrelations between all study variables among boys and girls are presented in Table 2. As may be expected, a more positive attributional style was negatively associated with NSSI at baseline and most follow-up time points. Also as expected, both baseline and 18-month follow-up measures of depressive symptoms were significantly and positively correlated with NSSI at baseline and most follow-up time points, as well as significantly and negatively correlated with baseline (“adaptive”) attributional style.

TABLE 2.

Pearson Correlations Among Primary Study Variables by Gender

| Variable | NSSI Baseline |

NSSI 3 Months |

NSSI 6 Months |

NSSI 9 Months |

NSSI 15 Months |

NSSI 18 Months |

CASQ- R Baseline |

LE Interpersonal |

CDI Baseline |

CDI 9 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSI – Baseline | — | .67*** | .51** | .12 | .10 | .52** | −.38* | −.18 | .52** | .11 |

| −3 months | .40** | — | .64*** | .11 | .24 | .53** | −.42* | .08 | .37* | .23 |

| −6 months | .50*** | .35** | — | .24 | .61** | .24 | .04 | .22 | .19 | .18 |

| −9 months | .22 | .12 | .27* | — | .16 | .15 | .06 | −.34 | .38* | .36* |

| −15 months | .49*** | .35** | .56*** | .28* | — | .12 | .28 | .12 | .08 | .38 |

| −18 months | .45*** | .27* | .57*** | .34** | .42*** | — | −.59** | −.02 | .51** | .35 |

| CASQ-R | −.36*** | −.38** | −.16 | −.14 | −.25* | −.33** | — | .07 | −.46** | −.13 |

| LE –Interpersonal | .11 | −.04 | .01 | −.26 | −.06 | −.02 | .02 | — | −.30 | −.14 |

| CDI – Baseline | .48*** | .34** | .22 | .12 | .36** | .33** | −.57*** | .02 | — | .48** |

| −9 months | .34** | .36** | .22 | .44*** | .44*** | .23 | −.45*** | −.02 | .34** | — |

Note: Boys above diagonal, girls below. NSSI =Nonsuicidal self-injury; CASQ-R =Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire–Revised; LE-Interpersonal =interpersonal life events; CDI =Child Depression Inventory.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Course of NSSI Over Time

The analysis of unconditional growth curve models began with an examination of a one slope model including baseline, 3-, 6-, 9-, 15-, and 18-month measures of NSSI. The model was a poor fit, χ2(12) =62.11, p < .001 (χ2/df =5.18, comparative fit index [CFI] =.65, normed fit index [NFI] =.62, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] =.17, Akaike’s information criterion [AIC] =92.11). This one slope model then was compared to a piecewise, linear spline model with a first latent slope factor representing the slope between baseline, 3-, and 6-month time points, and a second slope factor representing changes between 9, 15, and 18 months. Path weights for the first latent slope factor were set to 0 at baseline, allowed to freely vary at 3 months, and set to 1 at 6 months (additional time point paths set to 1). For the second slope factor, path weights were allowed to freely vary at both 9 and 15 months but were set to 1 at 18 months (additional time point paths set to 0). This model yielded a good fit, χ2(9) =9.83, ns (χ2/df =1.09, CFI =.99, NFI =.94, RMSEA =.03, AIC =45.83), and was a better fit to the data than was the single slope model.

A third model with a quadratic slope factor also was modeled. This curvilinear model included an initial slope function with paths to baseline, 3-, 6-, 9-, 15-, and 18-month measures of NSSI set to indicate the 3-month intervals (i.e., 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6, respectively) and a second slope function with paths to each corresponding time point squared (i.e., 0, 2, 4, 9, 25, and 36, respectively). The fit for the quadratic model, χ2(12) =30.98, p < .01 (χ2/df =2.58, CFI =.86, NFI =.81, RMSEA =.10, AIC =60.98), was not better than the initial slope model, and fit substantially worse than did the piecewise model.

Because of its good fit, the piecewise model was used as the starting point upon which all analyses listed next were built. The estimated unstandardized path weight for NSSI at 3 months post-baseline on the first slope factor was .96 (p < .001), and for NSSI at 9 and 15 months post-baseline on the second slope factor were 1.56 and −4.65, respectively (ns each). Estimated intercept parameters were M =1.53 (p < .001). Estimated parameters for the first slope factor (M = −.37, p < .001) indicated declining levels of NSSI between baseline, 3, and 6 months post-baseline (i.e., an NSSI remission slope). However, estimated parameters for the second slope factor for NSSI between 9, 15, and 18 months postbaseline were not significant, indicating, on average, consistent levels of NSSI across this period (M =.02, ns; i.e., an NSSI maintenance slope).

Baseline Cognitive Vulnerability-Stress Interaction as a Predictor of NSSI Trajectories

The next goal of analyses was to build upon the unconditional growth curve model listed above to examine central study hypotheses related to the prospective prediction of NSSI trajectories. Three exogenous predictors were added to the model just listed: (a) attributional style, (b) interpersonal life events, and (c) the interaction between interpersonal life events and attributional style. Baseline depressive symptoms also was included as an exogenous predictor as a rigorous control (i.e., to ensure that other variables were not simply serving as a proxy for depressive symptoms). In addition, depressive symptoms as measured at 9 months post-baseline were included in the model. As a preliminary step to examine mediation, paths were estimated between each of the three exogenous predictors just listed and depressive symptoms at 9 months post-baseline, and a path between depressive symptoms at 9 months post-baseline and the NSSI “maintenance slope” (i.e., between 9 and 18 months) was estimated. Paths were estimated between all predictors and the latent intercept and both NSSI slopes were estimated. All predictors were allowed to covary. The fit of this model was satisfactory, χ2(29) =58.71, p < .001 (χ2/df =2.02, CFI =.88, RMSEA =.10).

Of importance, results from this model suggested that depressive symptoms at 9 months post-baseline was not a significant predictor of the NSSI maintenance slope (between 9 and 18 months; β =−.11, p =.18). In addition, no significant effect was revealed between the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction term and depressive symptoms at 9 months (β =.02, p =.62); thus, preliminary support required to formally test mediation was not obtained. A reduced model removing depressive symptoms at 9 months therefore was examined. The fit of this reduced model was good, χ2(21) =33.55, p < .05 (χ2/df =1.60, CFI =.94, RMSEA =.08). All unstandardized path weights from this reduced model are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Prediction of NSSI from Exogenous Predictors

| NSSI

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Remission Slope | Maintenance Slope | |

| LE-int | .05 (.05) | −.04 (.05) | −.01 (.02) |

| Attributional Style (CASQ-R) | −.09 (.06) | .06 (.06) | −.05 (.03) |

| CASQ-R × LE-int | −.08 (.05) | −.01 (.05) | −.07 (.03)* |

| Baseline Depression (CDI) | .98 (.18)** | −.62 (.16)** | .06 (.08) |

Note: Parameters reported in the table are unstandardized regression weights (and standard errors). NSSI =nonsuicidal self-injury; CASQ-R =Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire-Revised; LE-int =interpersonal life events; CDI =Child Depression Inventory.

p < .05.

p < .001.

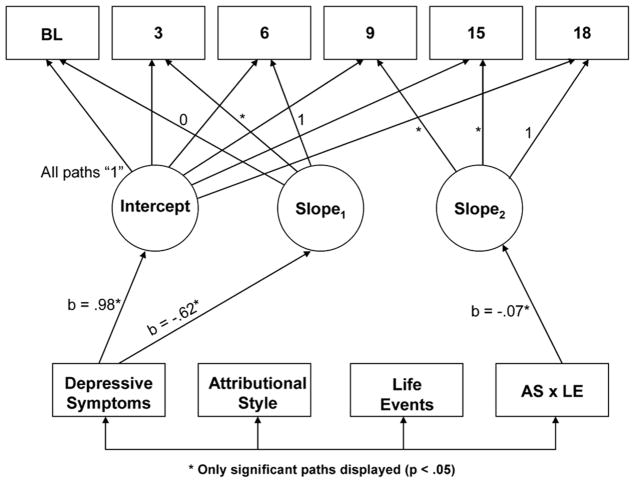

Three associations consistent with hypotheses were revealed. First, higher levels of depressive symptoms reported at baseline were associated with higher levels of baseline NSSI (i.e., intercept). No other baseline measure emerged as a significant predictor of baseline NSSI. Second, higher levels of depressive symptoms also were associated with a lower NSSI “remission slope” (i.e., Slope 1) during the first 6 months of follow-up, above and beyond all other estimated associations. This indicated that higher levels of baseline depressive symptoms were associated with attenuated NSSI recovery over this longitudinal interval. Finally, after accounting for the associations between all other exogenous predictors and the NSSI “maintenance slope” (i.e., Slope 2), the interaction between negative attributional style and stressful life events emerged as the only significant predictor of NSSI between 9, 15, and 18 months post-baseline (see Figure 1). These results suggested that individuals who reported a more negative attributional style in conjunction with the experience of a greater number of stressful interpersonal life events tended to report increasing trajectories of NSSI between 9 and 18 months post-baseline.1

FIGURE 1.

Conditional growth curve model depicting the longitudinal prediction of nonsuicidal self-injury from baseline exogenous predictors. Note: BL =baseline measure of nonsuicidal self-injury; 3, 6, 9, 15, and 18 =correspond to month (post-baseline) measures of nonsuicidal self-injury; AS × LE =interaction of attributional style and interpersonal life events.

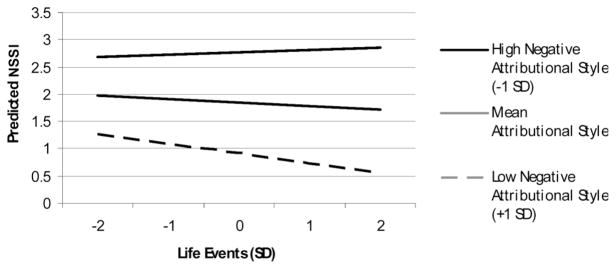

Figure 2 displays NSSI simple slopes for high negative attributional style (−1 SD), mean attributional style, and low negative (i.e., adaptive) attributional style (+1 SD) across increasing levels of stressful life events. Findings suggested that only under conditions of high negative attributional style, higher levels of stressful life events were longitudinally associated with higher levels of NSSI between 9 and 18 months post-baseline. This pattern of results also was confirmed in regression analyses using baseline levels of NSSI, depressive symptoms, stressful life events, attributional style, and the interaction of the latter two variables as predictors of NSSI as measured at 18 months post-baseline. Computation of slope estimates indicated that only under conditions of high levels of negative attributional style, higher levels of stressful life events were longitudinally associated with higher levels of NSSI (b =1.15, β =.44, p < .01). In contrast, under conditions of lower levels of negative attributional style, higher levels of stressful life events were longitudinally associated with lower levels of NSSI (b =−1.03, β =−.39, p < .01).

FIGURE 2.

Predicted nonsuicidal self-injury between 9 months and 18 months post-baseline as a function of baseline attributional style and stressful life events (based on conditional latent growth curve model parameter estimates).

DISCUSSION

NSSI is becoming recognized increasingly as a significant public health problem, occurring at surprisingly high rates both within community and clinical samples. Although recent research has suggested that high levels of emotional distress may immediately precede NSSI engagement, and that these behaviors may serve the function of regulating aversive emotional stimuli, no longitudinal research has been conducted on NSSI to date. In addition, it has been found that self-injuring adolescents display higher physiological reactivity in response to stress, a lower threshold of distress tolerance, and associated deficits in social problem-solving abilities (Nock & Mendes, 2008). Little is known, however, regarding how distal factors may confer risk for the maladaptive stress-response conditions which have been hypothesized to precede episodes of NSSI. In other words, it is unclear whether adolescents at risk for eventual NSSI may respond to stressful life events in a unique way that may lead to difficulties with emotional reactions to stress or whether they possess other unique long-term risks for NSSI. This longitudinal study utilized a cognitive vulnerability-stress model to examine whether attributions of negative life events may be prospectively associated with NSSI engagement. In addition, given the relevance of the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction to the longitudinal prediction of depressive symptoms, as well as the strong concurrent association between NSSI and depression, we simultaneously examined whether depressive symptoms served as an independent predictor of NSSI and/ or a mediator of the association between cognitive vulnerability-stress and NSSI.

As the first longitudinal investigation of NSSI, an initial goal of this study was to examine the frequency of these behaviors in a clinically-referred sample of adolescents. NSSI indeed was remarkably prevalent in this sample; slightly more than two thirds of adolescents reported that they had engaged in some form of NSSI over the year preceding baseline hospital admission. Comparably high rates have been found in studies of NSSI among similar inpatient samples of adolescents (e.g., ~61%; DiClemete et al., 1991). At 3 months subsequent to discharge, however, the reported prevalence of NSSI declined sharply to approximately one third of the sample and then remained relatively stable over the extended 18-month follow-up period. The marked decrease from baseline levels of NSSI at follow-up could be expected given that adolescents were admitted to the hospital during the peak of psychiatric crisis when the incidence of NSSI would likely be at its highest. Presumably, these patients would thereafter be discharged only when this crisis had abated (i.e., following a course of inpatient treatment, after which they were determined to no longer be at risk for imminent self-harm, etc.). Mirroring the NSSI longitudinal drop-off and providing further support for the notion of general improvement following hospital discharge, adolescents reported significantly lower levels of depression at 9-month follow-up than they had at baseline.

Consistent with some previous work (e.g., Bhugra et al., 2003; Ross & Heath, 2002), a number of gender differences in NSSI were found suggesting unique vulnerabilities among adolescent girls. As past studies examining gender differences in NSSI have yielded mixed results, a careful examination of gender at different developmental periods may be important for elucidating differential patterns of NSSI behavior among boys and girls. In this sample, youths were at the transition to adolescence; this period may be particularly critical for girls’ vulnerabilities to NSSI, as has been demonstrated with depressive symptoms (Hankin & Abramson, 2001).

A primary goal of this study was to examine NSSI trajectories and longitudinal prediction of NSSI within an inpatient sample of adolescents. Analyses indicated that the average course of NSSI in this sample included a period of substantial NSSI remission during the first 6 months following hospitalization (i.e., an NSSI “remission slope”), followed by a year in which NSSI remained stable and relatively infrequent (i.e., an NSSI “maintenance slope”). It may be that NSSI accompanies crises similar to those that precipitate inpatient hospitalization and, as these crises abate, frequencies of NSSI may stabilize. Alternatively, it is possible that certain measurement inconsistencies have exaggerated the observed decline in NSSI between baseline and 6-month follow-up; in responding to questions about the frequency with which they engage in NSSI, participants were asked to consider the time frame of the past year at baseline but the preceding 3 months at subsequent assessments.

Results revealed few predictors of NSSI frequency in the first 6 months following hospital discharge. In fact, only baseline depressive symptoms emerged as a predictor of NSSI remission during this period. Predictably, higher levels of depression were associated with an attenuated decline in NSSI over this longitudinal interval. It may be that individuals who continued to experience marked emotional distress experienced slower decreases in NSSI post-discharge. Baseline life events and attributional style were not related to NSSI during this period, perhaps due to increased attention and monitoring that frequently accompanies—and often directly follows—a course of inpatient treatment (e.g., Walker, Joiner, & Rudd, 2001).

Consistent with hypotheses, a cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction emerged as a significant predictor of NSSI between 9 and 18 months post-baseline (i.e., the NSSI “maintenance slope”). Individuals who possessed more negative attributional styles in conjunction with the experience of a greater number of stressful interpersonal life events tended to report increasing levels of NSSI over time, after accounting for a sample-wide trend of maintaining NSSI levels. The persistence of this effect is particularly impressive when considered in context. First, the substantial length of the longitudinal interval provides a rigorous test of the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction. It is remarkable that the interaction of the single baseline measures of negative attributional style and stressful interpersonal life events remains a significant predictor of engagement in NSSI 1½ years later. Second, this effect is significant above and beyond that accounted for by depressive symptoms as measured at 9 months post-baseline, and this association was not significantly mediated by depressive symptoms at this time point. These results suggest the multifinality of this cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction; it may be that the predictive effect of this model on future NSSI does not simply serve as a proxy for the effects of depressive symptoms. Third, the true size of such an interaction effect may have been considerably underestimated in this study due to certain limitations related to the measurement of study constructs. Perhaps the most obvious of these is the use of the revised CASQ-R as our measure of “cognitive vulnerability.” Recent research has suggested that the CASQ-R may not be preferable to more recently developed measures of attributional style with better psychometric properties and stronger face validity (e.g., Lakdawalla et al., 2007). Thus, it is remarkable that an interaction between baseline negative attributional style and stressful interpersonal life events remained a significant predictor of long-term adolescent NSSI. Although these findings are preliminary and in need of replication, we believe that the current research has highlighted a potentially fruitful and important avenue for research into the development of a dangerous and persistent self-injurious behavior.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Results have important clinical implications. It is possible that individuals who engage in NSSI or those predisposed to such behaviors may suffer from a certain kind of emotion dysregulation, beyond that which could be simply explained by symptoms of depression. Our findings suggest that individuals who experience interpersonal life stressors and interpret these stressors as due to internal, global, and stable causes are not only at risk for depressive symptoms, but perhaps also a pattern of stress reactivity that leads to engagement in maladaptive coping behaviors (e.g., NSSI) to deal with overwhelming negative affect. Accordingly, it may be useful to reconceptualize and broaden the implications of “depressogenic” cognitive vulnerability-stress interactions. It is possible that the interaction between negative attributional style and stressful life events serves as an important, distal predictor of at least two possibly independent but more often overlapping outcomes, namely, (a) the onset or exacerbation of general sadness or more melancholic features of depressive symptomatology (e.g., flattened affect, anhedonia, etc.) and/or (b) the initiation of acute negative arousal or the perpetuation of more chronic affective agitation, with ensuing reductions in adaptive coping. We hypothesize that this latter, stress-generation/stress maintenance outcome may be more associated with engagement in NSSI. Consistent with this idea, symptoms of other clinical diagnoses were evident in this sample (e.g., GAD, PTSD, conduct disorder); these symptoms may reflect related difficulties with emotion dysregulation.

Indeed, recent work suggests that adolescents and young adults who engage in NSSI experience both higher levels of negative affect and exhibit significantly lower levels of distress tolerance than those without histories of NSSI (Armey & Crowther, 2008; Crowell et al., 2008; Klonsky & Olino, 2008; Nock & Mendes, 2008). Proximally, at-risk individuals or individuals with a history of NSSI could be taught to replace habitual, self-destructive behavior with healthier, more adaptive strategies when faced with the experience of overwhelming negative affect. Alternatively, more distal strategies could be targeted to at-risk individuals toward preventing patterns of cognitive responses to stress that promote overwhelming emotional states and reactions to stress.

As an initial longitudinal study of NSSI and its distal predictors, this study offers several important contributions. Nevertheless, future research would benefit by addressing several important limitations. For instance, it is unfortunate that the sample size in this study did not allow for an examination of gender differences in the longitudinal trajectories of NSSI. This is a crucial direction for future research. In addition, the relatively small sample size available to examine this complex model also may have limited the potential to reveal other important associations. For instance, the examination of Cognitive Vulnerability × Life Stress as a predictor of depressive symptoms in the context of a larger model also examining NSSI outcomes may have been underpowered in this study.

The study of cognitive vulnerability-stress theories also would benefit from greater attention to specific vulnerability theories (see Abramson et al., 1989; Beck, 1987). This hypothesis maintains that an individual may possess one or more “specific vulnerabilities” (e.g., an achievement-related vulnerability vs. an interpersonal vulnerability) that typically remain latent until activated or “triggered” by a relevant stressor (e.g., “I failed a test” vs. “I broke up with my boyfriend,” respectively). Unfortunately, our use of the 24-item CASQ-R did not allow for the separate, domain-specific examination of interpersonally relevant attributions as this would further reduce internal consistency and render the measure unusable. Thus, examining attributions for specifically measured types of stressors, rather than global attributional style (as was measured here), may be a useful avenue in future studies. Last, no prior research has adequately examined ethnic and socioeconomic status differences in NSSI or its predictors. There is urgent need for research in this area.

Overall, results from this study suggest that long-term prediction of NSSI may be possible. By revealing preliminary support for the cognitive vulnerability-stress hypothesis, findings indicate that cognitive responses to interpersonal stress deserve attention not only in the prediction of depressive symptoms but also NSSI.

Footnotes

The negative association revealed between the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction and the NSSI “maintenance slope” may seem counterintuitive. Recall that more negative (i.e., “depressogenic”) attributional styles are represented by more extreme negative numbers, whereas positive (i.e., “adaptive”) attributional styles are represented by increasing positive numbers (see the Methods section regarding Attributional Style for a more detailed explanation). Greater mean occurrences of stressful life events, on the other hand, are represented by increasing positive numbers. Therefore, for the multiplicative interaction term, more extreme negative numbers represent higher relative levels of risk (i.e., greater reported levels of cognitive vulnerability in conjunction with more numerous interpersonal stressors). Thus, our data indicate that higher levels of the cognitive vulnerability-stress interaction (i.e., greater negative terms) are longitudinally associated with increasing trajectories of NSSI (i.e., greater positive terms) between 9 and 18 months postbaseline. The converse association also follows.

References

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hogan ME, Whitehouse WG, Donovan P, Rose DT, et al. Cognitive vulnerability to depression: Theory and evidence. In: Leahy RL, Dowd ET, editors. Clinical advances in cognitive psychotherapy: Theory and application. New York: Springer; 2002. pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Armey MF, Crowther JH. A comparison of linear versus non-linear models of aversive self-awareness, dissociation, and nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:9–14. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1987;1:5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra D, Thompson N, Singh J, Fellow-Smith E. Inception rates of deliberate self-harm among adolescents in West London. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2003;49:247–250. doi: 10.1177/0020764003494002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boergers J, Spirito A. Follow-up studies of child and adolescent suicide attempters. In: King RA, Apter A, editors. Suicide in children and adolescents. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 271–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models. A structural equation perspective. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:609–620. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MZ, Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:198–202. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary MP, Faulstich ME, Gresham FM, Ruggiero L, Enyart P. Children’s depression inventory: Construct and discriminant validity across clinical and nonreferred (control) populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:755–761. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2006;44:371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane R, Robertson A. Stress in the lives of parasuicides. Social Psychiatry. 1975;10:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington RD. The significance of life events as etiological factors in the diseases of children. II. A study of a normal population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1972;16:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(72)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Davis GE, Forsythe CJ, Wagner BM. Assessment of major and daily stressful events during adolescence: The adolescent Perceived Events Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:534–541. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.55.4.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, McCauley E, Smith CJ, Vasilev CA, Stevens AL. Parent–child interactions, peripheral serotonin, and self-inflicted injury in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:15–21. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darche MA. Psychological factors differentiating self-mutilating and non-self mutilating adolescent inpatient females. Psychiatric Hospital. 1990;21:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE, Hartley D. Prevalence and correlates of cutting behavior: Risk for HIV transmission. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favazza AR. The coming of age of self-mutilation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:259–268. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199805000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favazza AR, Conterio K. The plight of chronic self-mutilators. Community Mental Health Journal. 1988;24:22–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00755050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favazza AR, DeRosear L, Conterio K. Self-mutilation and eating disorders. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 1989;19:352–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Addy CL, McKeown RE, Cuffe SP, Jackson KL, Waller JL. Nonsuicidal physically self-damaging acts in adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1993;2:339–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GH, Simons RL. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0002-9432.72.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines J, Williams CL, Brain KL, Wilson GV. The psychophysiology of self-mutilation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:471–489. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Fagg J, Simkin S, Bale E, Bond A. Trends in deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1985–1995. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;171:556–560. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsman R, Garber J. A test of the cognitive diathesis-stress model of depression in children: Academic stressors, attributional style, perceived competence, and control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:370–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Cha CB, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:63–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Nock MK, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury among young adolescents: Rates, correlates, and prelininary test of an interpersonal model. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:455–469. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Miranda J, Segal ZV. Cognitive vulnerability to depression. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JH, McCutcheon SM. Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the Life Events Checklist. In: Sarason IG, Spielberger CD, editors. Stress and anxiety. Washington, D.C: Hemisphere; 1980. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire—Revised. Emory University; Atlanta, GA: 1991. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Assessment of childhood depression. In: La Greca AM, editor. Through the eyes of the child: Obtaining self-reports from children and adolescents. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1990. pp. 189–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, French NH, Unis AS, Esveldt-Dawson K. Assessment of childhood depression: Correspondence of child and parent ratings. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1983;22:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)62329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Olino TM. Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:22–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1501–1508. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawalla Z, Hankin BL, Mermelstein R. Cognitive theories of depression in children and adolescents: A conceptual and quantitative review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology. 2007;10:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Ham M. Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Joiner TE, Rohde P. Evaluation of cognitive diathesis stress models in predicting major depressive disorder in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:203–215. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Garmezy N, Tellegen A, Pellegrini DS, Larkin K. Competence and stress in school children: The moderating effects of individual and family qualities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1988;29:745–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1988.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Mendes WB. Physiological arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem-solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:28–38. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Guerry JD, Browne CB, Rancourt D. Interpersonal models of nonsuicidal self-injury. In: Nock MK, editor. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Heath N. A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;311:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C. Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development. 1999;70:660–677. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Finch AJ, Baskin CH, Furey W, Kelly MM. Construct validity for measures of childhood depression: Application of mult trait-method methodology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:977–985. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Finch AJ, Spirito A, Bennett B. The children’s depression inventory: A systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:955–967. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Ingram RE, Segal ZV. Cognitive reactivity and vulnerability: Empirical evaluation of construct activation and cognitive diatheses in unipolar depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from preivous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suyemoto KL. The functions of self-mutilation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:531–554. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Kaslow NJ, Weiss B, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire–Revised: Psychometric examination. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Walker RL, Joiner TE, Jr, Rudd MD. The course of post-crisis suicidal symptoms: How and for whom is suicide “cathartic”? Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2001;31:144–152. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.2.144.21514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip K. A multi-dimensional perspective of adolescents’ self-cutting. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2005;10:80–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]