Abstract

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is characterized by a tendency for recurrence and capacity for progression. Intravesical instillation therapy has been employed in various clinical settings, which are summarized within this review. Several chemotherapeutic agents have shown clinical efficacy in reducing recurrence rates in the post-transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) setting, including mitomycin C (MMC), doxorubicin, and epirubicin. Mounting evidence also supports the use of intravesical MMC following nephroureterectomy to reduce later urothelial bladder recurrence. In the adjuvant setting, bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy is an established first-line agent in the management of carcinoma in situ (CIS) and high-grade non muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma (UC). Among high and intermediate-risk patients (based on tumor grade, size, and focality) improvements in disease-free intervals have been seen with adjunctive administration of MMC prior to scheduled BCG dosing. Following failure of first-line intravesical therapy, gemcitabine and valrubicin have demonstrated modest activity, though valrubicin remains the only agent currently Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of BCG-refractory CIS. Techniques to optimize intravesical chemotherapy delivery have also been explored including pharmacokinetic methods such as urinary alkalization and voluntary dehydration. Chemohyperthermia and electromotive instillation have been associated with improved freedom from recurrence intervals but may be associated with increased urinary toxicity. Improvements in therapeutic selection may be heralded by novel opportunities for genomic profiling and refinements in clinical risk stratification.

Keywords: Intermediate risk, intravesical chemotherapy, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

INTRODUCTION

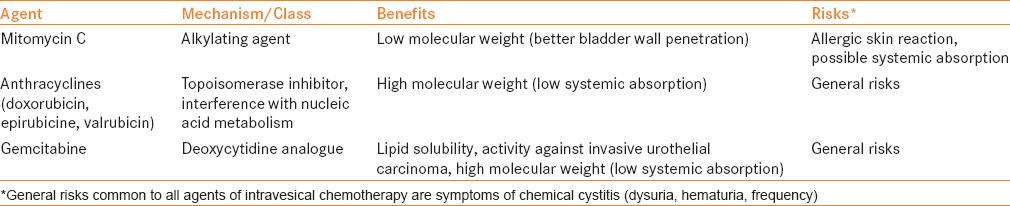

Superficial or non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) accounts for approximately 70% of patients presenting with the disease and includes both low- and high-grade tumors, at stages Ta, T1, or carcinoma in situ (CIS). NMIBC is usually not immediately life-threatening, unlike its muscle-invasive counterpart, but is characterized by significant rates of recurrence and potential for progression. Rates of recurrence range 50-80%, and progression 10-45%, depending on disease risk (based upon grade, stage, multifocality, and tumor size).[1,2] Intravesical therapy aims to decrease these possibilities and is instilled directly into the bladder. Two major therapeutic classes are used for this purpose: Immunotherapy with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), and chemotherapy, which is the subject of the current review. Table 1 describes common chemotherapeutic agents, mechanisms of actions, and possible side effects including mitomycin C (MMC, the most widely used), anthracyclines, and gemcitabine. A literature review was performed focusing on the past 15 years to identify contemporary articles regarding intravesical chemotherapy. Articles were then organized by the predefined clinical scenario categories, and the manuscripts with the highest level of evidence were included.

Table 1.

Intravesical chemotherapeutic agents

USE OF INTRAVESICAL CHEMOTHERAPY BASED ON CLINICAL SCENARIO

Immediate post-operative instillation

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) is the mainstay of both diagnosis and treatment of NMIBC, and provides both the stage and the basis of risk stratification. Despite visually complete resection, there is a high rate of recurrence in patients with NMIBC, possibly due to implantation of tumor cells after TURBT or residual but not visible disease.[3] Sylvester et al. performed a comprehensive meta-analysis compiling clinical trials examining almost 1500 patients and found a reduction in recurrence rate from 48.4% to 36.7% (11.7%) in patients receiving immediate (within 24 h) instillation of intravesical chemotherapy [P < 0.001 with odds ratio (OR) 0.61].[4] MMC, doxorubicin, and epirubicin showed benefit; however, epirubicin is not currently available in the United States.[5] This benefit appears to be greatest in solitary, low-volume tumors. Intravesical gemcitabine does not have a role in this setting, as a phase 3 randomized controlled trial (RCT) performed on over 350 patients did not show benefit as was seen for other agents, when compared to placebo (P = 0.777).[6]

Current American Urologic Association (AUA) guidelines and European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines both recommend the use of intravesical chemotherapy immediately after TURBT.[7] Instillation should not be done in any situation of bladder perforation or suspected bladder perforation, as severe complications have been described due to chemotherapy extravasation.[8] Recently, this principle has been extrapolated to patients undergoing nephroureterectomy for upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. Fang et al., performed a systematic review and meta-analysis examining five clinical trials of over 600 patients who received intravesical chemotherapy after nephroureterectomy. MMC was utilized in three of five trials, and treatment was given 1-2 weeks after initial surgery. A 41% decrease in odds of recurrence was observed in those treated with intravesical chemotherapy (P = 0.0001), with no serious adverse events. Based on these promising results, intravesical chemotherapy should be used not only after TURBT, but also after nephroureterectomy. Currently, there is no substantial evidence to extrapolate intravesical chemotherapy after ureteroscopy for upper-tract urothelial carcinoma to prevent intravesical recurrence; however, studies are underway to determine efficacy.

Adjuvant instillation of intravesical chemotherapy

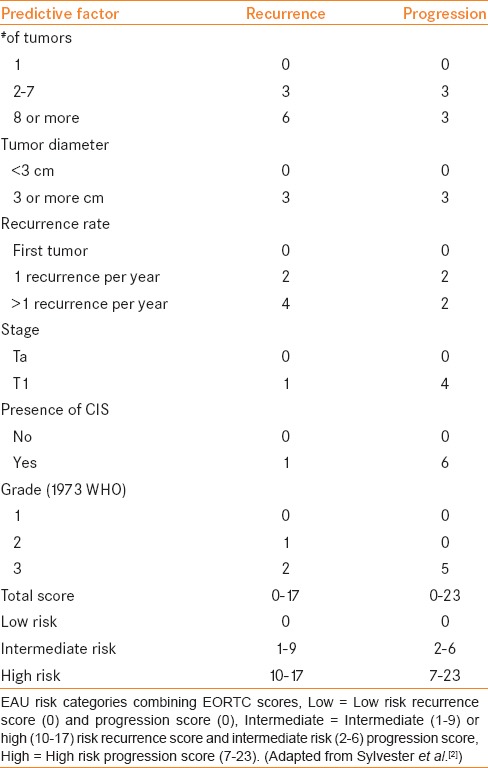

In patients with a small (<3 cm), solitary, low-grade (i.e., low-risk) tumor, single intravesical instillation of chemotherapy alone as described above is the standard of care.[4] Subsequent instillations of intravesical chemotherapy, or adjuvant chemotherapy is considered necessary for higher-risk disease. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) incorporated readily available clinical and pathologic criteria (in addition to grade and stage) in a multivariable risk model to develop a scoring system predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients. Risk factors were identified from over 2,500 patients with NMIBC who participated in seven clinical trials. Six important predictors were identified: Tumor grade, clinical T stage, presence of concomitant CIS, number of tumors, tumor diameter, and prior recurrence rate.[2,9] Table 2 is adapted from these results.[2] The EAU risk category definition based on the EORTC calculator likely provides the most precise risk classification other than consensus definitions (i.e. AUA), is the most widely used, and will provide the basis of defining risk in the current review.[10]

Table 2.

EORTC scoring system to classify disease risk in patients with NMIBC

First-line therapy

Current evidence suggests that the most appropriate clinical situation for adjuvant intravesical chemotherapy as first-line therapy is in the setting of intermediate-risk disease. Based on the EAU risk stratification system, patients with intermediate-risk disease have a recurrence rate of 38% [35-41%, 95% confidence interval (CI)] at 1 year and 62% (59-65%, 95% CI) at 5 years. The rate of progression is clinically significant but lower at 6% (5-8%, 95% CI) at 5 years.[2] Lammers et al. examined rates of recurrence and progression in approximately 1,000 Dutch patients with NIMBC treated with intravesical chemotherapy stratified by risk using various guideline definitions, and found that those who were undertreated (regardless of definition used) had worse outcomes.[11] Specifically in the group with intermediate risk of recurrence and progression, those who were undertreated (i.e., no additional intravesical chemotherapy aside from perioperative instillation) had significantly more recurrences (P = 0.016) and progression (P < 0.001).

As discussed above, all patients should receive immediate instillation of chemotherapy after TURBT and, likely, further intravesical chemotherapy. However, the type, schedule, duration, and whether intravesical BCG should be used in lieu of adjuvant chemotherapy in intermediate-risk patients is unknown and of much debate due to conflicting evidence. Huncharek et al. compiled 11 RCTs, including over 3,000 patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy compared to TURBT alone, and found an absolute decrease in recurrence of 14% in the absence of low-risk disease.[12] When compared to intravesical BCG, intravesical chemotherapy was seen to be inferior in patients with intermediate-risk disease (using sub-analyses) in three RCTs, comparing it to epirubicin ± interferon-a2b and MMC.[13,14,15] A subsequent meta-analysis found this to be true only in the setting of BCG maintenance, where an additional 32% reduction in risk of recurrence was observed compared to MMC in nine RCTs involving almost 3,000 patients.[16] Differences in the reduction of rates of progression in this patient group were even more heterogenous. In the same meta-analysis of almost 3,000 patients, there was no difference between MMC or BCG in disease progression.[16] When compared with epirubicin, BCG was found to be superior, with an increased disease specific survival and less metastasis, albeit low overall event rate.[15] Horvath et al. reviewed therapeutic options in patients with intermediate-risk disease and confirmed that this group is extremely heterogeneous, with a wide window of both recurrence and progression risk.[17] In fact, the “intermediate risk group” is most often comprised of patients included from well-defined low or high-risk categories. Most likely, conflicting evidence is due to this fact, along with the low number of events (in the case of progression), variation in follow up, and trial design.

In light of the diversity of this population stemming from various causes, the International Bladder Cancer Group (IBCG) performed a systematic review of the literature to develop practical recommendations, including the appropriate use of intravesical chemotherapy in patients with intermediate-risk disease.[18] Kamat et al. determined that within the category of intermediate-risk tumors, if patients have 1-2 out of 4 risk factors (multiple tumors, size >3 cm, early recurrence <1 year, or frequent recurrences >1 per year) and have had no previous intravesical therapy, intravesical chemotherapy might be the best first-line agent. If intravesical chemotherapy has already been used in an adjuvant fashion or there are 3+ risk factors, then BCG with maintenance is recommended. It should be noted that this recommendation is based on expert opinion and in patients classified as intermediate risk by mostly multiple or recurrent low-grade tumors. Ofude et al. recently analyzed retrospective data from 262 patients with NMIBC. Of this group, 57 patients had weekly instillations of intravesical chemotherapy and 90 patients had intravesical BCG therapy.[19] Patients were then risk-stratified based on the EORTC score for recurrence (0-17), focusing on substratification of the intermediate risk group (1-9) into two groups 1-4 and 5-9, which encompassed the majority of this population. On multivariate analysis, with an increase in EORTC score, the efficacy of BCG intravesical therapy in decreasing recurrence risk heightened, favoring BCG over intravesical chemotherapy (MMC or epirubicin). In patients with an EORTC score of 5-9, BCG performed better in preventing recurrence than weekly chemotherapy (Hazard Ratio 2.43, P < 0.034). Of note, prior recurrence rate, tumor size >3 cm, and number of tumors were also independent predictors of recurrence in this cohort, similar to the risk factors defined above by Kamat et al. Tumor grade was also significant, echoing the summary recommendations by the ICBG refining the definition of intermediate-risk patients appropriate for first-line intravesical chemotherapy.

The correct schedule for instillation of intravesical chemotherapy has not been well defined; however, based on clinical trials already described above and a compiled meta-analysis, it generally follows similar schemas for intravesical BCG therapy and consists of 5-6 weekly instillations (induction), followed by monthly or quarterly maintenance instillations.[12,13,14,15] Additionally, EAU guidelines state that there is no available evidence that supports intravesical chemotherapy instillations for longer than 1 year.[20]

Adjunct therapy

Intravesical immunotherapy with BCG induction (and maintenance) is indicated as first-line treatment for patients with high-risk tumors (as defined above based on the EORTC risk calculator, or considered on the more aggressive spectrum of intermediate-risk disease).[21,22] The addition of intravesical chemotherapy to BCG as an adjunct was recently examined in a meta-analysis of 800 patients in four clinical trials.[23] Benefit to combined chemo-immunotherapy appeared to be restricted to patients with Ta and T1 disease (not CIS), as reductions in rates of recurrence and progression were not significant unless the single trial that allowed for patients with CIS was removed from analysis. When the remaining three trials were compiled, the risk of recurrence (Relative Risk 0.75; 95% CI 0.61-0.92; P = 0.006) and progression (RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.25-0.81; P = 0.007) were reduced with the addition of chemotherapy (epirubicin/MMC) without additional toxicity. Zhu et al., performed a similar meta-analysis including more studies and determined that there was a small potential benefit to epirubicin + BCG; however, epirubicin was given more than 1 week prior to BCG for the majority of patients.[24] The highest-quality data in support of combined chemo-immunotherapy is from the recently published RCT in 407 patients demonstrating that sequential intravesical therapy with MMC given the day prior to BCG is more effective than BCG alone.[25] Patients with intermediate- to high-risk disease had a decrease in relapse rate from 34% to 21%, translating to an improved disease-free interval. The authors did note higher toxicity with the combination therapy, and concluded that only in those with the highest-risk tumors (recurrent high-grade T1) was the toxicity benefit ratio in favor of combined chemo-immunotherapy. No difference was seen in progression-free survival, which may be related to the absence of maintenance therapy in this cohort.

Salvage therapy

The use of intravesical chemotherapy in patients with recurrence of NMIBC after appropriate BCG is one strategy for bladder preservation. Failure of BCG therapy can be defined in many different ways: 1) progression to muscle-invasive disease; 2) high-risk NIMBC at 3 months and 6 months (both) after diagnosis; 3) worsening of disease while on BCG (including CIS); 4) recurrence of high-risk disease less than 1 year after initial response. Cystectomy should be offered to all patients with BCG failure, as survival is excellent and delay may lead to worse outcomes.[26] However, not all recurrences or BCG failures are created equal. EAU guidelines do allow for intravesical chemotherapy after BCG in patients with a non-high-grade recurrence for a primary intermediate-risk tumor.[7] MMC, gemcitabine, valrubicin, and docetaxel have all been evaluated in the salvage setting as single agents or in combination therapy.

Gemcitabine has been evaluated in an RCT by Di Lorenzo et al., who compared it to repeat BCG in patients with refractory disease, with a significant decrease in recurrence from 88% to 52% at just over 1 year median follow-up (P < 0.008).[27] Sternberg et al. reported a complete response rate of approximately 30% with intravesical gemcitabine in 69 patients with various types of BCG failure.[28] Lightfoot et al. grouped 47 patients from three academic centers who were given sequential intravesical combination chemotherapy using gemcitabine and MMC after failing previous intravesical therapy.[29] Recurrence free survival at 2 years was 38% with 30% remaining free of disease at 26 months median follow up. Although not ideal, these rates are better than that of MMC alone, which is ineffective after BCG failure.[30] Only 19% of patients who were treated with MMC in a salvage setting were recurrence free at 3 years.

Valrubicin is currently the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved agent for use in patients with BCG-refractory CIS who are not candidates for radical cystectomy. Dinney et al. reported on long-term outcomes in 80 patients treated with valrubicin for refractory disease that showed an 18% complete response rate with a 4% recurrence-free survival at 2 years.[31] Docetaxel was evaluated by Barlow et al. in 54 patients with recurrent disease after BCG. Approximately two-thirds had their bladder in situ at median 3-year follow up.[32] Recurrence-free survival was 25% at 3 years. A recent phase 2 study of intravesical nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel showed promising results, with a 36% response rate at median follow-up of 21 months with minimal toxicity in a small group of 28 patients.[33] Combinations of chemotherapeutic agents and the optimization of existing agents (as discussed below) are currently under clinical investigation to improve upon options for patients either unwilling or unfit to undergo cystectomy in the face of BCG failure.

OPTIMIZING INTRAVESICAL CHEMOTHERAPY

As described above, intravesical chemotherapy has clinical efficacy and overall favorable tolerability for the treatment NMIBC. Efforts to potentiate drug action and further improve patient outcomes have been investigated, including pharmacokinetic techniques to maximize drug delivery and contact time and strategies to enhance the absorption and action of the drug. The majority of these efforts were for optimization of MMC intravesical chemotherapy, and that is the focus of this section.

Techniques to optimize passive diffusion MMC delivery

Urinary alkalization, MMC dose escalation (40 mg versus 20 mg), and voluntary dehydration to decrease urinary volume have been proposed as means to maximize therapeutic benefit.[34,35] The effect of these pharmacologic interventions was investigated in a randomized phase III trial of 230 patients receiving pharmacokinetic manipulations or urinary alkalization compared with standard treatment alone among patients treated with a 6-week course of intravesical MMC for NMIBC, in which optimized patients experienced a longer median time to recurrence (29.1 months versus 11.8 months, P = 0.005).[36] Patients randomized to receive optimized therapy reported higher rates of dysuria (33.3% versus 17.9%), however, did not experience increased rates of discontinuation.

Active optimization strategies

Hyperthermia

Thermal manipulation of MMC has been shown to enhance cytotoxic action against tumor cells across several mechanisms.[37] Chemohyperthermic delivery of MMC has been examined in the setting of higher-risk spectrum patients with NMIBC achieved via an indwelling bladder radiofrequency applicator. In a prospective, multicentered trial of 83 patients with NMIBC randomized to receive microwave induced chemohyperthermia versus standard MMC demonstrates a significant reduction in local recurrence rates at 24 months follow: 17.1% versus 57.5%, and an enduring difference in extended follow-up.[38] Improvements in recurrence rates appear to be in exchange for increases in treatment-related lower urinary tract symptoms including pain, dysuria, and bladder spasms, which may limit the widespread clinical adoption of heated MMC in the treatment paradigm for NMIBC.

Electromotive therapy

Electromotive drug administration (EMDA) of MMC involves the delivery of an electric current through the bladder. In a prospective study, Di Stasi et al. compared 20 mA EMDA of MMC therapy with passive MMC, and BCG therapy in 108 patients with high-risk superficial bladder cancer.[39] Electromotive therapy was associated with a complete response rate of 58%, compared with 31% for standard MMC therapy at 6 months (P = 0.012), and resulted in higher peak-plasma MMC concentrations. The role of electromotive instillation of MMC before transurethral resection has also been explored in a RCT comparing pre-TURBT EMDA of MMC with TURBT alone or passive MMC post-procedure.[40] Patients receiving EMDA MMC prior to TURBT experienced a significantly longer disease-free interval when compared with resection alone and with passive delivery of MMC therapy alone: 52 months versus 16 months and versus 12 months (P < 0.001).[41] These encouraging findings remain to be replicated in a broader clinical experience, where rates of progression and cancer-specific survival may be further elucidated.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Potential avenues of future studies are with novel therapeutics (targeted therapies, chromatin-modifying agents) as adjuncts to intravesical chemotherapy to improve outcomes in patients with higher risk or recurrent disease. Additionally, as genomic profiling becomes readily available and possible using small amounts of tissues, the prediction of chemosensitivity may help guide patients who are likely to respond to treatment, aside from traditional clinicopathologic factors.

CONCLUSIONS

Intravesical chemotherapy has a critical role in the treatment paradigm of NMIBC. Current evidence supports the use of intravesical chemotherapy within 24 hr after TURBT (favorable toward MMC) and shortly after nephroureterctomy for upper-tract disease (1-2 weeks) to prevent bladder recurrence of NIMBC. Based on available data and expert opinion intravesical chemotherapy for specific patients with intermediate-risk disease (consisting of mainly multifocal or recurrent low-grade is an appropriate first-line adjuvant therapy, otherwise BCG with maintenance should be used. An appropriate schedule is currently unknown but should consist of an induction course with maintenance (similar to BCG) and should not exceed 1 year in duration. In higher-risk disease states, adding intravesical chemotherapy (MMC) to BCG can improve outcomes, but in exchange for higher toxicity, and therefore should only be considered in the highest-risk patients (recurrent high-grade T1). In the salvage setting, gemcitabine (±MMC) appears to have the most promising activity, as well as methods to optimize existing regimens; further studies with longer follow-up are needed to determine the best combinations and the modifications with the least toxicity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sylvester RJ. Natural history, recurrence, and progression in superficial bladder cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:2617–25. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA, Bouffioux C, Denis L, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: A combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49:466–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. discussion 475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oosterlinck W, Kurth KH, Schröder F, Bultinck J, Hammond B, Sylvester R. A prospective European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Genitourinary Group randomized trial comparing transurethral resection followed by a single intravesical instillation of epirubicin or water in single stage Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 1993;149:749–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36198-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, van der Meijden AP. A single immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 2004;171:2186–90. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125486.92260.b2. quiz 2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gudjónsson S, Adell L, Merdasa F, Olsson R, Larsson B, Davidsson T, et al. Should all patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer receive early intravesical chemotherapy after transurethral resection? The results of a prospective randomised multicentre study. Eur Urol. 2009;55:773–80. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Böhle A, Leyh H, Frei C, Kühn M, Tschada R, Pottek T, et al. S274 Study Group. Single postoperative instillation of gemcitabine in patients with non-muscle-invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III multicentre study. Eur Urol. 2009;56:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babjuk M, Burger M, Zigeuner R, Shariat SF, van Rhijn BW, Compérat E, et al. European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: Update 2013. Eur Urol. 2013;64:639–53. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oddens JR, van der Meijden AP, Sylvester R. One immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy in low risk Ta, T1 bladder cancer patients. Is it always safe? Eur Urol. 2004;46:336–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, Kaasinen E, Böhle A, Palou-Redorta J, et al. European Association of Urology (EAU) EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol. 2011;59:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olivier Bosset P, Neuzillet Y, Paoletti X, Molinie V, Botto H, Lebret T. Long-term follow-up of TaG1 non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:20.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lammers RJ, Palou J, Witjes WP, Janzing-Pastors MH, Caris CT, Witjes JA. Comparison of expected treatment outcomes, obtained using risk models and international guidelines, with observed treatment outcomes in a Dutch cohort of patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer treated with intravesical chemotherapy. BJU Int. 2014;114:193–201. doi: 10.1111/bju.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huncharek M, McGarry R, Kupelnick B. Impact of intravesical chemotherapy on recurrence rate of recurrent superficial transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: Results of a meta-analysis. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:765–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duchek M, Johansson R, Jahnson S, Mestad O, Hellström P, Hellsten S, et al. Members of the Urothelial Cancer Group of the Nordic Association of Urology. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin is superior to a combination of epirubicin and interferon-alpha2b in the intravesical treatment of patients with stage T1 urinary bladder cancer. A prospective, randomized, Nordic study. Eur Urol. 2010;57:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Järvinen R, Kaasinen E, Sankila A, Rintala E FinnBladder Group. Long-term efficacy of maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin versus maintenance mitomycin C instillation therapy in frequently recurrent TaT1 tumours without carcinoma in situ: A subgroup analysis of the prospective, randomised FinnBladder I study with a 20-year follow-up. Eur Urol. 2009;56:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sylvester RJ, Brausi MA, Kirkels WJ, Hoeltl W, Calais Da Silva F, Powell PH, et al. EORTCGenito-Urinary Tract Cancer Group. Long-term efficacy results of EORTC genito-urinary group randomized phase 3 study 30911 comparing intravesical instillations of epirubicin, bacillus Calmette-Guérin, and bacillus Calmette-Guérin plus isoniazid in patients with intermediate- and high-risk stage Ta T1 urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Eur Urol. 2010;57:766–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malmström PU, Sylvester RJ, Crawford DE, Friedrich M, Krege S, Rintala E, et al. An individual patient data meta-analysis of the long-term outcome of randomised studies comparing intravesical mitomycin C versus bacillus Calmette-Guérin for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;56:247–56. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horvath A, Mostafid H. Therapeutic options in the management of intermediate-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2009;103:726–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamat AM, Witjes JA, Brausi M, Soloway M, Lamm D, Persad R, et al. Defining and treating the spectrum of intermediate risk nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2014;192:305–15. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ofude M, Kitagawa Y, Yaegashi H, Izumi K, Ueno S, Kadono Y, et al. Selection of adjuvant intravesical therapies using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer scoring system in patients at intermediate risk of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:161–8. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1795-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, Witjes JA. The schedule and duration of intravesical chemotherapy in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review of the published results of randomized clinical trials. Eur Urol. 2008;53:709–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamm DL. Efficacy and safety of bacille Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy in superficial bladder cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(Suppl 3):S86–90. doi: 10.1086/314064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, Montie JE, Gottesman JE, Lowe BA, et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette- Guérin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: A randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol. 2000;163:1124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houghton BB, Chalasani V, Hayne D, Grimison P, Brown CS, Patel MI, et al. Intravesical chemotherapy plus bacille Calmette-Guérin in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A systematic review with meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2013;111:977–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu S, Tang Y, Li K, Shang Z, Jiang N, Nian X, et al. Optimal schedule of bacillus Calmette-Guerin for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of comparative studies. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solsona E, Madero R, Chantada V, Fernandez JM, Zabala JA, Portillo JA, et al. Members of Club Urológico Español de Tratamiento Oncológico. Sequential combination of mitomycin C plus Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Is more effective but more toxic than BCG alone in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer in intermediate- and high-risk patients: Final outcome of CUETO 93009, a randomized prospective trial. Eur Urol. 2015;67:508–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulkarni GS, Alibhai SM, Finelli A, Fleshner NE, Jewett MA, Lopushinsky SR, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of immediate radical cystectomy versus intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy for high-risk, high-grade (T1G3) bladder cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:5450–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Lorenzo G, Perdonà S, Damiano R, Faiella A, Cantiello F, Pignata S, et al. Gemcitabine versus bacille Calmette-Guérin after initial bacille Calmette-Guérin failure in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: A multicenter prospective randomized trial. Cancer. 2010;116:1893–900. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sternberg IA, Dalbagni G, Chen LY, Donat SM, Bochner BH, Herr HW. Intravesical gemcitabine for high risk, nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer after bacillus Calmette-Guérin treatment failure. J Urol. 2013;190:1686–91. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lightfoot AJ, Breyer BN, Rosevear HM, Erickson BA, Konety BR, O’Donnell MA. Multi-institutional analysis of sequential intravesical gemcitabine and mitomycin C chemotherapy for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:35.e15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malmström PU, Wijkström H, Lundholm C, Wester K, Busch C, Norlén BJ. 5-year followup of a randomized prospective study comparing mitomycin C and bacillus Calmette-Guerin in patients with superficial bladder carcinoma. Swedish-Norwegian Bladder Cancer Study Group. J Urol. 1999;161:1124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinney CP, Greenberg RE, Steinberg GD. Intravesical valrubicin in patients with bladder carcinoma in situ and contraindication to or failure after bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1635–42. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barlow LJ, McKiernan JM, Benson MC. Long-term survival outcomes with intravesical docetaxel for recurrent nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer after previous bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. J Urol. 2013;189:834–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKiernan JM, Holder DD, Ghandour RA, Barlow LJ, Ahn JJ, Kates M, et al. Phase II trial of intravesical nanoparticle albumin bound paclitaxel for the treatment of nonmuscle invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder after bacillus Calmette-Guérin treatment failure. J Urol. 2014;192:1633–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wientjes MG, Badalament RA, Au JL. Use of pharmacologic data and computer simulations to design an efficacy trial of intravesical mitomycin C therapy for superficial bladder cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1993;32:255–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00686169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wientjes MG, Dalton JT, Badalament RA, Dasani BM, Drago JR, Au JL. A method to study drug concentration-depth profiles in tissues: Mitomycin C in dog bladder wall. Pharm Res. 1991;8:168–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1015827700904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Au JL, Badalament RA, Wientjes MG, Young DC, Warner JA, Venema PL, et al. InternationalMitomycin C Consortium. Methods to improve efficacy of intravesical mitomycin C: Results of a randomized phase III trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:597–604. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Heijden AG, Verhaegh G, Jansen CF, Schalken JA, Witjes JA. Effect of hyperthermia on the cytotoxicity of 4 chemotherapeutic agents currently used for the treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: An in vitro study. J Urol. 2005;173:1375–80. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000146274.85012.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colombo R, Salonia A, Leib Z, Pavone-Macaluso M, Engelstein D. Long-term outcomes of a randomized controlled trial comparing thermochemotherapy with mitomycin-C alone as adjuvant treatment for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) BJU Int. 2011;107:912–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Stasi SM, Giannantoni A, Stephen RL, Capelli G, Navarra P, Massoud R, et al. Intravesical electromotive mitomycin C versus passive transport mitomycin C for high risk superficial bladder cancer: A prospective randomized study. J Urol. 2003;170:777–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000080568.91703.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Stasi SM, Valenti M, Verri C, Liberati E, Giurioli A, Leprini G, et al. Electromotive instillation of mitomycin immediately before transurethral resection for patients with primary urothelial non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:871–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Stasi SM, Giannantoni A, Giurioli A, Valenti M, Zampa G, Storti L, et al. Sequential BCG and electromotive mitomycin versus BCG alone for high-risk superficial bladder cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:43–51. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]