Abstract

Background:

The incidence of abdominal trauma is still underreported from the Arab Middle-East. We aimed to evaluate the incidence, causes, clinical presentation, and outcome of the abdominal trauma patients in a newly established trauma center.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective analysis was conducted at the only level I trauma center in Qatar for the patients admitted with abdominal trauma (2008-2011). Patients demographics, mechanism of injury, pattern of organ injuries, associated extra-abdominal injuries, Injury Severity Score (ISS), Abbreviated Injury Scale, complications, length of Intensive Care Unit, and hospital stay, and mortality were reviewed.

Results:

A total of 6888 trauma patients were admitted to the hospital, of which 1036 (15%) had abdominal trauma. The mean age was 30.6 ± 13 years and the majority was males (93%). Road traffic accidents (61%) were the most frequent mechanism of injury followed by fall from height (25%) and fall of heavy object (7%). The mean ISS was 17.9 ± 10. Liver (36%), spleen (32%) and kidney (18%) were most common injured organs. The common associated extra-abdominal injuries included chest (35%), musculoskeletal (32%), and head injury (24%). Wound infection (3.8%), pneumonia (3%), and urinary tract infection (1.4%) were the frequently observed complications. The overall mortality was 8.3% and late mortality was observed in 2.3% cases mainly due to severe head injury and sepsis. The predictors of mortality were head injury, ISS, need for blood transfusion, and serum lactate.

Conclusion:

Abdominal trauma is a frequent diagnosis in multiple trauma and the presence of extra-abdominal injuries and sepsis has a significant impact on the outcome.

Keywords: Abdominal trauma, mortality, Qatar, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

Trauma is the main cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide[1,2] and is still the most frequent cause of death in the first four decades of life.[3] Moreover, it remains a major public health problem among all countries, regardless of the socioeconomic status.[4,5] Abdomen is the third most frequently injured body region and about 25% of all abdominal trauma cases require abdominal exploration.[6,7] Usually, abdominal injuries occur either due to blunt or penetrating trauma, and around 7-10% of all trauma-related deaths occurred due to these injuries.[8,9] An earlier study on major blunt abdominal trauma reported an overall mortality of 42%, and massive intra-abdominal hemorrhage was identified as the frequent cause of early mortality following multiple trauma.[10] Costa et al.[11] reported motor vehicle crashes (MVCs), fall from height and assaults to be the most common causes of blunt abdominal trauma. The penetrating trauma is mainly caused by gunshot, stab, and other objects that enter the peritoneal cavity.

Since the discovery of oil, Qatar has experienced a rapid growth in socioeconomic status which resulted in high motorization rate that leads to increased MVCs.[12] Moreover, economic growth in Qatar has led to the remarkable increase in incidence of MVCs, occupational injuries, as well as assaults and stab injuries resulting in the death and the disability.[13] In 2001, one report from Qatar showed that in MVCs, the abdominal injury patients constituted 0.45% of total trauma admissions and 12.6% of all admitted cases to the surgical Intensive Care Unit (ICU).[14] Otherwise, there is lack of detailed information on the incidence and the outcome of abdominal injuries from our region, particularly after establishing a new trauma center in 2007. Herein, the present study aims to evaluate the incidence, causes, pattern, and the outcomes of abdominal trauma in Qatar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It is a retrospective analysis of the data obtained from the trauma registry at Hamad General Hospital, the only level I trauma center in Qatar which was queried for patients admitted with abdominal trauma from January 2008 to December 2011. Our trauma ICU is up-to-date unit as a part of the only level I trauma center in Qatar and it received the trauma distinction award from accreditation Canada international. All patients’ ≥14 years who sustained blunt, as well as penetrating abdominal trauma were included in the study. The present analysis excluded the patients who died at the scene and was moved directly to the mortuary in addition to those who died after hospital discharge.

All trauma patients were initially resuscitated at the trauma room according to the advanced trauma life support guidelines. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan was performed in all hemodynamically stable patients who were suspected to have abdominal injury or were positive for Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma. Data regarding age, gender, mechanism of injury, pattern of solid organ injuries, associated extra-abdominal injuries, Injury Severity Score (ISS), Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), complications, length of ICU and the hospital stay, and mortality were reviewed. This study in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration was approved by the Medical Research Center (IRB# 12057/12) at Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar.

Data were expressed as percentages, mean ± standard deviation, and median and range whenever applicable. The multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for the predictors of in-hospital mortality after adjusting for the potential relevant variables (age, ISS head, lung, liver, spleen, and bowels injury, need for blood transfusion, sepsis, and serum lactate). Results were expressed as odds ratios (OR), with accompanying 95% confidence intervals. P < 0.05 was considered for significant difference. Data analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

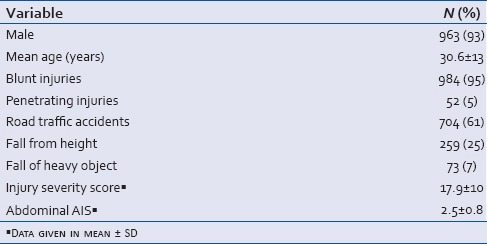

During the study period, a total of 6888 trauma patients were admitted to the hospital, of which 1036 (15%) had an abdominal trauma with a mean age of 30.6 ± 13 years and the majority of patients were males (93%). The majority of abdominal injury patients sustained blunt trauma (95%) and only 5% had penetrating injuries [Table 1]. MVCs were the most frequent mechanism of injury (61%) followed by fall from height (25%) and fall of heavy object (7%). The penetrating abdominal trauma was mainly due to stab (4.5%) wounds. The mean ISS was 17.9 ± 10 and abdominal AIS was 2.5 ± 0.8.

Table 1.

Patients demographic and basic data (n = 1036)

Pattern of abdominal organ injuries

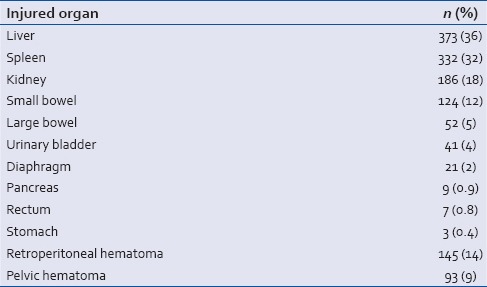

Among the abdominal organ injuries, liver (36%) and spleen (32%) were most common injured, followed by kidney (18%), small bowel (12%), large bowel (5%), urinary bladder (4%), and diaphragmatic (2%) injuries [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pattern of abdominal organ injuries (n = 1036)

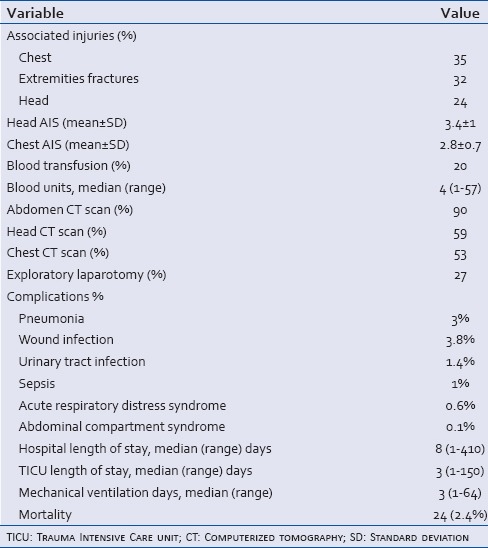

The most common associated extra-abdominal injuries included chest trauma (35%), musculoskeletal injury (32%), and head injury (24%). The mean head AIS was 3.4 ± 1 and the chest AIS was 2.8 ± 0.7. From the emergency department, 41% of the patients were admitted to trauma ICU, 25% were transferred to the operating room, and 34% were shifted to the ward. Exploratory laparotomy was performed in 27% of the cases [Table 3]. Wound infection (3.8%), pneumonia (3%), and urinary tract infection (1.4%) were the frequently observed complications. Blood transfusion was required in 19.7% of abdominal trauma cases. The mean number of units was 4 (1-57). It was given more frequently to those who died later in comparison to those who survived (61% vs. 15%, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Overall clinical profiles of abdominal injury (n = 1036)

The median length of the hospital stay was 8 (1-410) days, the trauma ICU stay was 3 (1-150) days and the median ventilatory days was 3 (1-64).

Outcome of abdominal injury

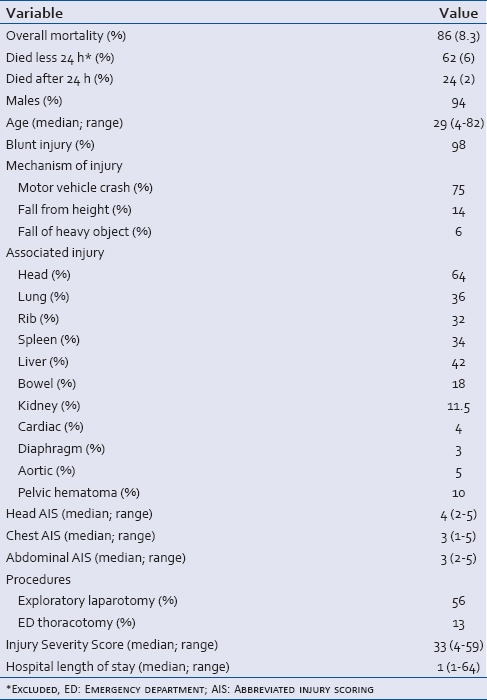

A total of 86 (8.3%) patients died in the study cohort, of whom 62 (6%) patients died within the first 24 h of hospital admission. The most common cause of death among these patients was unsalvageable traumatic brain injury (TBI), prehospital cardiopulmonary arrest and refractory shock from exsanguinating injuries. On the other hand, 24 (2.3%) patients died after 24 h of the hospital admission. Among these 24 patients, 14 died primarily due to severe TBI, 8 developed sepsis and multiorgan failure, one had rupture dissecting aorta, and one had Grade V liver injury with recurrent massive bleeding during postoperative course. The demographics and clinical presentations in patients who died with abdominal injury are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Demographics and clinical presentations in patients who died with abdominal injury

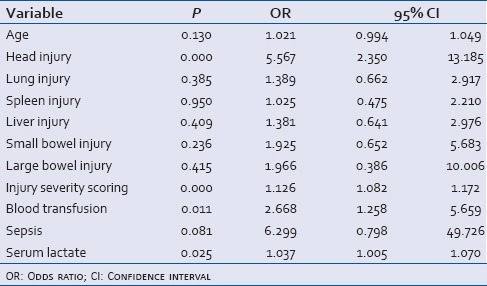

Multivariate logistic regression analysis [Table 5] showed that the main predictors of mortality were head injury (OR: 5.50. P < 0.001), need for blood transfusion (OR: 2.67, P = 0.01), ISS (OR: 1.12, P < 0.001), and serum lactate (OR: 1.04, P = 0.02).

Table 5.

Predictors of mortality among abdominal trauma patients

DISCUSSION

This study presents a unique description of the frequency, causes, clinical presentation, and outcome of the abdominal injury in Qatar after establishing the trauma system in 2007. Up to the best of our knowledge, there are only few reports that describe the incidence and the outcome of abdominal trauma from our region. Hamad General Hospital is the only level I trauma center in Qatar in which all the severely injured patients are admitted and treated. In our series, the estimated abdominal trauma cases in Qatar are around 15-17/100,000 and the number of abdominal injuries was higher among the young male population with a male to a female ratio of 13:1. Previous report from South Asia[15] demonstrated a male to a female ratio of 4.4:1 among abdominal trauma patients. Furthermore, in our study the higher proportion of patients who sustained abdominal injuries were young in their most productive age. Our findings are consistent with a recent study from Egypt.[16] It has been reported that trauma usually affects the young productive aged group that eventually poses economic burden to national economy, as well as on families.[17]

In our series, MVCs were the most common mechanism of abdominal trauma followed by fall from height which corroborates with earlier studies.[9,16] In addition to being male and young, the mechanism of injury in those patients reflects the rapid increases in the socioeconomic status and construction boom in Qatar. Tuma et al.[18] demonstrated increased morbidity and mortality among workers falling from height at a construction sites which pose a financial burden on the healthcare system of the country. Contrarily, penetrating injuries are relatively uncommon (5%) in our study than earlier studies.[15,19]

Particularly, among multiple trauma patients, abdomen is the third most frequently injured body part.[20] Moreover, several studies have reported liver to be the most common injured solid organs followed by spleen in blunt abdominal trauma.[21,22,23] Consistently, in our study, the most frequently injured abdominal organ includes liver, followed by Spleen, and kidneys. However, other studies have reported spleen to be the most common injured abdominal organ.[17,20,24,25] For instance, patients in some areas in Africa have splenomegaly due to chronic tropical infections that render them more susceptible to splenic rupture with even minor trauma.[24]

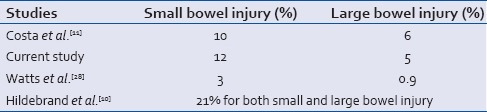

Although, hollow viscous injuries after blunt trauma are rare; it remains the third most common injury in blunt abdominal trauma[26] and had a reported incidence of 1-2% of all blunt trauma cases.[27,28] Costa et al.[11] reported the incidence of small bowel injury to be 10% whereas large bowel injury was identified in 6% of abdominal trauma patients.[11] Similar to this study, we have also observed 12% incidence of small bowel injuries whereas 5% cases had large bowel injuries. Furthermore, Hildebrand et al.[10] reported an overall incidence of hollow viscous injuries to be 21% in blunt abdominal trauma patients requiring laparotomies. In contrast, a large multi-center study has reported relatively lower incidence of hollow viscous injury (small bowel: 3% and colon injuries: 0.9%) from the United States.[28] Table 6 shows the proportion of traumatic bowel injury from different countries.

Table 6.

Small and large bowel involved in traumatic injury

Moreover, the current study found chest injuries to be the most common observed concomitant extra-abdominal injuries, followed by the extremities, and head injuries. Similarly, Mohamed et al.[29] from Saudi Arabia reported chest and head injury to be the most frequently associated extra-abdominal injuries in polytrauma patients.

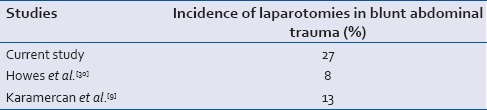

Howes et al.[30] included all blunt torso trauma patients admitted at the metropolitan trauma service in South Africa and the authors observed that only 8% of blunt abdominal trauma patients required laparotomy. In contrast, 27% our patients underwent laparotomies. Another, study from Turkey reported that emergency laparotomies were performed in 13% of the blunt abdominal trauma cases.[9] Table 7 shows Incidence of laparotomies after blunt abdominal trauma in different studies.

Table 7.

Proportion of laparotomies in trauma patients

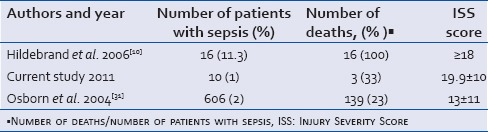

Sepsis or multiple organ dysfunction syndrome after severe abdominal trauma remains a substantial challenge and is expected to be the cause of late mortality. The overall incidence of sepsis in our study was 1%, which are relatively comparable to that reported by Osborn et al.,[31] where the incidence of sepsis was 2%. In contrast, an earlier study reported an incidence of sepsis following abdominal trauma of 11.3%.[10] In our study, the lower incidence of sepsis could be related in part to the young healthy patients with no associated comorbidities. In Osborn et al. study,[31] the incidence of sepsis was low as the majority of patients sustained mild injury with mean ISS of 12.9 and minimal physiological abnormality on admission. The 2% of patients who developed sepsis had moderate to severe injury with higher ISS score of 28.1 (±14.2).

Moreover, in our series, the incidence of sepsis-related mortality was 33% as compared to 9% mortality in nonseptic patients. Osborn et al.[31] reported a significant association of sepsis with increased mortality. However, an earlier study observed lower incidence of sepsis-related mortality in blunt abdominal trauma patients.[10] The trauma care has been improved over the past decade with better management in the ICU with mechanical ventilation, better sepsis control, early recognition of complication, early antibiotics use, and nutrition in addition to early mobilization. However, there are no studies comparing the outcome of sepsis management based on the delivered trauma care over different era and from different geographic areas. A large retrospective study from Germany reported that 10.2% of the severe polytrauma patients developed sepsis during their hospital course.[32] The authors found that over 15 years, even though the overall mortality from multiple trauma patients decreased significantly, the incidence of sepsis-related mortality remains unchanged. In general, development of sepsis is associated with worse outcomes in trauma patients and remained a challenging complication after polytrauma. Table 8 shows the incidence of sepsis and mortality in 2 studies in comparison to ours. These studies were inconsistent in regard with the ISS scores.

Table 8.

Sepsis and mortality in different studies

Musau et al.[33] from Nigeria reported an overall mortality of 12.5% among abdominal injury patients. Another prospective study on blunt abdominal trauma observed an overall mortality of 26% and half of these patients died of multiple organ failure secondary to sepsis.[30] In comparison to other studies, the overall mortality in our cohort group was very low (2.4%). Nevertheless, the cause-specific mortality was relatively high, and the mortality was mainly related to severe head injury (58%) and sepsis (33%). The main predictors of mortality in the current study were head injury (with high median AIS score of 4) and need for blood transfusion; the former was associated with 5 times increase in the mortality whereas, the latter was associated with 3-fold increase in the mortality.

Overall, the complication rate was low in our study where the most frequently observed complication was wound infection (3.8%), followed by pneumonia (3%), urinary tract infection (1.4%), and sepsis (1%). While a total of 86 (8.3%) patients died in the study, 62 (6%) patients died within 24 h of the hospital admission, and 23 (2.3%) patients died after 24 h. We observed a median length of hospital and ICU stay of 8 and 3 days, respectively.

One of the major limitations of the present study is the retrospective design. Also, data obtained from the registry did not perfectly include detailed operative findings or brought-in-dead patients’ information. Moreover, there was no follow-up for patients after hospital discharge from the initial traumatic event.

CONCLUSION

Abdominal trauma is a frequent diagnosis in multiple trauma patients and the presence of extra-abdominal injuries particularly TBI has significant impact on the outcomes. Also the presence of sepsis is a major contributor of late morbidity and mortality. Moreover, MVCs and occupational injuries are the primary mechanisms of abdominal trauma that mainly involve young males in Qatar. Therefore, relevant injury prevention programs and stringent road traffic regulations would likely to minimize the occurrence and outcomes of abdominal trauma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the database registry staff of the trauma section. This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector. All authors have read and approved the manuscript, no conflict of interest and no financial issues to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger LR, Mohan D. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press; 1996. Injury Control: A Global View. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potenza BM, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Fortlage D, Holbrook T, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, et al. The epidemiology of serious and fatal injury in San Diego County over an 11-year period. J Trauma. 2004;56:68–75. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000101490.32972.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker SP, O’Neil B, Ginsburg MJ, Li G. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. The Injury Fact Book. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldemir M, Taçyildiz I, Girgin S. Predicting factors for mortality in the penetrating abdominal trauma. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:429–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2011. [Last accessed on 2014 May 11];National Vital Statistics Reports. 2012 61 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsend CM, Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier-Saunders; 2008. Sabiston Text Book of Surgery, the Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice; p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemmila MR, Wahl WL. Management of injured patient. In: Dorethy GM, editor. Current Surgical Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2008. pp. 227–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fabian TC, Croce MA, Minard G, Bee TK, Cagiannos C, Miller PR, et al. Current issues in trauma. Curr Probl Surg. 2002;39:1160–244. doi: 10.1067/msg.2002.128499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karamercan A, Yilmaz TU, Karmercan MA, Aytac B. Blunt abdominal trauma: Evaluation of diagnostic options and surgical outcomes. Turk J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;14:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrand F, Winkler M, Griensven MV, Probst C, Musahl V, Krettek C, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma requiring laparotomy: An analysis of 342 polytraumatized patients. Eur J Trauma. 2006;32:430–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa G, Tierno SM, Tomassini F, Venturini L, Frezza B, Cancrini G, et al. The epidemiology and clinical evaluation of abdominal trauma. An analysis of a multidisciplinary trauma registry. Ann Ital Chir. 2010;81:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bener A, Hussain SJ, Al-Malki MA, Shotar MM, Al-Said MF, Jadaan KS. Road traffic fatalities in Qatar, Jordan and the UAE: Estimates using regression analysis and the relationship with economic growth. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:318–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Sheikly AS. Pattern of trauma in the districts of Doha/Qatar: Causes and suggestions. J Med Res. 2012;1:25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmi I, Hussein A, Ahmed AH. Abdominal trauma due to road traffic accidents in Qatar. Injury. 2001;32:105–8. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(00)00155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lone GN, Peer GQ, Warn AK, Bhat AM, Warn NA. An experience with abdominal trauma in adults in Kashmir. JK Pract. 2001;8:225–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gad MA, Saber A, Farrag S, Shams ME, Ellabban GM. Incidence, patterns, and factors predicting mortality of abdominal injuries in trauma patients. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4:129–34. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.93889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salimi J, Ghodsi M, Zavvarh MN, Khaji A. Hospital management of abdominal trauma in Tehran, Iran: A review of 228 patients. Chin J Traumatol. 2009;12:259–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuma MA, Acerra JR, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Al-Hassani A, Recicar JF, et al. Epidemiology of workplace-related fall from height and cost of trauma care in Qatar. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3:3–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.109408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baradaran H, Salimi J, Zaverh MN, Khaji A, Rabbani A. A epidemiological study of patients with penetrating abdominal trauma in Tehran-Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2007;45:305–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdelrahman H, Ajaj A, Atique S, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H. Conservative management of major liver necrosis after angioembolization in a patient with blunt trauma. Case Rep Surg 2013. 2013:954050. doi: 10.1155/2013/954050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith J, Caldwell E, D’Amours S, Jalaludin B, Sugrue M. Abdominal trauma: A disease in evolution. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:790–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clancy TV, Gary Maxwell J, Covington DL, Brinker CC, Blackman D. A statewide analysis of level I and II trauma centers for patients with major injuries. J Trauma. 2001;51:346–51. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthes G, Stengel D, Seifert J, Rademacher G, Mutze S, Ekkernkamp A. Blunt liver injuries in polytrauma: Results from a cohort study with the regular use of whole-body helical computed tomography. World J Surg. 2003;27:1124–30. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponifasio P, Poki HO, Watters DA. Abdominal trauma in urban Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2001;44:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Dass RM, Mbelenge N, Ngayomela IH, Chandika AB, et al. Injury characteristics and outcome of road traffic crash victims at Bugando Medical Centre in Northwestern Tanzania. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2012;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wisner DH, Chun Y, Blaisdell FW. Blunt intestinal injury. Keys to diagnosis and management. Arch Surg. 1990;125:1319–22. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410220103014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Hassani A, Tuma M, Mahmood I, Afifi I, Almadani A, El-Menyar A, et al. Dilemma of blunt bowel injury: What are the factors affecting early diagnosis and outcomes. Am Surg. 2013;79:922–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watts DD, Fakhry SM. EAST Multi-Institutional Hollow Viscus Injury Research Group. Incidence of hollow viscus injury in blunt trauma: An analysis from 275,557 trauma admissions from the East multi-institutional trial. J Trauma. 2003;54:289–94. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000046261.06976.6A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohamed AA, Mahran KM, Zaazou MM. Blunt abdominal trauma requiring laparotomy in poly-traumatized patients. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howes N, Walker T, Allorto NL, Oosthuizen GV, Clarke DL. Laparotomy for blunt abdominal trauma in a civilian trauma service. S Afr J Surg. 2012;50:30–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osborn TM, Tracy JK, Dunne JR, Pasquale M, Napolitano LM. Epidemiology of sepsis in patients with traumatic injury. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2234–40. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000145586.23276.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wafaisade A, Lefering R, Bouillon B, Sakka SG, Thamm OC, Paffrath T, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of sepsis after multiple trauma: An analysis of 29,829 patients from the Trauma Registry of the German Society for Trauma Surgery. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:621–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206d3df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musau P, Jani PG, Owillah FA. Pattern and outcome of abdominal injuries at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2006;83:37–43. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v83i1.9359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]