Abstract

We lately reported the cases of patients complaining positional vertigo whose nystagmic pattern was that of a peripheral torsional vertical positional down beating nystagmus originating from a lithiasis of the non-ampullary arm of the posterior semicircular canal (PSC). We considered this particular pathological picture the apogeotropic variant of PSC benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Since the description of the pilot cases we observed more than 150 patients showing the same clinical sign and course of symptoms. In this paper we describe, in detail, both nystagmus of apogeotropic PSC BPPV (A-PSC BPPV) and symptoms reported by patients trying to give a reasonable explanation for these clinical features. Moreover we developed two specific physical therapies directed to cure A-PSC BPPV. Preliminary results of these techniques are related.

Key words: positional vertigo, down beating nystagmus, apogeotropic variant, demi Semont, 45° forced prolonged position

Introduction

In a recent paper1 we described a variant of posterior semicircular canal (PSC) benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), which characteristically presents with a torsional vertical down beating positional nystagmus (TVP-DBNy) when the patient is brought into head hanging positions (Dix-Hallpike’s positioning and the enhanced head-hanging position2). Our preliminary study took in consideration the cases of 6 patients complaining mostly positional vertigo, manifesting TVP-DBNy and, for that, initially diagnosed as having anterior semicircular canal (ASC) BPPV. Patients were treated with some physical therapy suitable for vertical canal BPPV (namely the ASC) and, surprisingly, they presented to a next visit with a torsional vertical paroxysmal positional up beating nystagmus suggesting a typical BPPV of the PSC of the side opposite to the one treated.

Since it is unlikely that therapy immediately resolves ASC BPPV of one side and that, at the same time (sometimes during the same diagnostic session), PSC BPPV of the other side manifests, we argued that the BPPV treated was of the PSC since the beginning.

In analogy with the homologous lateral semicircular canal (LSC) variant we named this form the apogeotropic PSC BPPV (A-PSC BPPV).

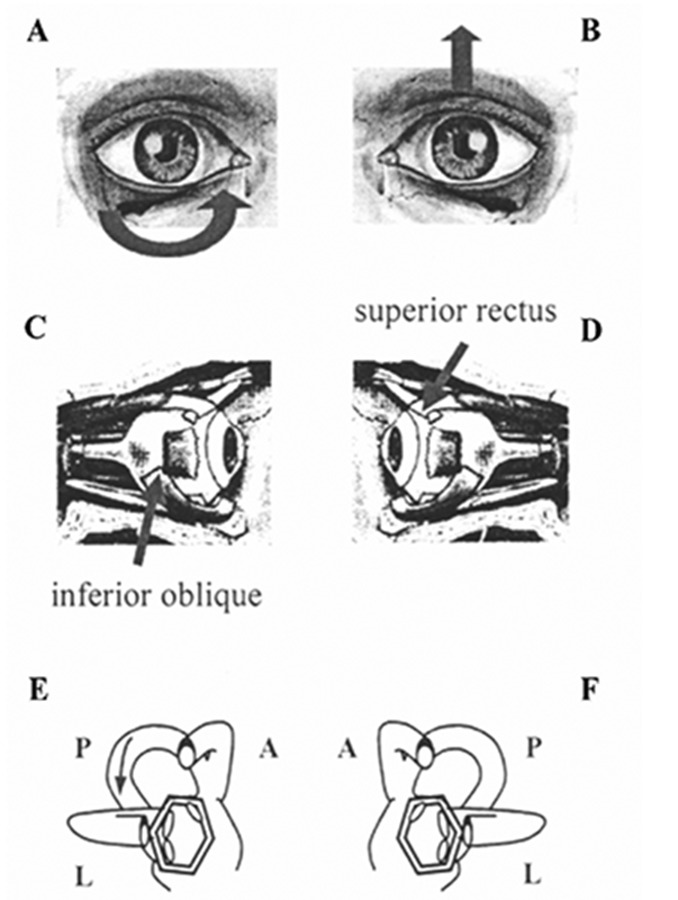

To explain TVP-DBNy of A-PSC BPPV we hypothesized a canalolithiasis3-5 having the otoconial mass localized into the distal part of non-ampullary arm of PSC, near the common crus. In such a case when the patient lays down into head hanging positions, the debris should move towards the ampulla producing an ampullopetal endolymphatic flow thus generating an inhibitory discharge of the posterior ampullary nerve. Such a stimulus, in turn, generates a paroxysmal or simil-paroxysmal (that is with a crescendo-decrescendo course but less intense and longer than usual and sometimes not completely exhaustible) vertical torsional nystagmus, due to the contraction of ipsilateral inferior oblique and contralateral superior rectus muscles.6 Slow phase of positional nystagmus is directed mainly upwards, with regard to the linear component, being counterclockwise or clockwise (from examiner’s point of view) for the torsional component, respectively for right and left PSC involvement (Figure 1). The torsional component is, theoretically, more evident in the eye ipsilateral to the affected PSC.

Figure 1.

Paroxysmal positional nystagmus due to unilateral right posterior semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (inhibitory stimulus). A and B) Arrows indicate the direction of nystagmus slow phase in the two eyes; C and D) arrows indicate the ocular muscles involved in nystagmus generation; E and F) the two labyrinths; arrow indicates the endolymphatic flow within the affected canal. A, C and E) The right eye and the right labyrinth; B, D and F) the left eye and the left labyrinth. A, anterior semicircular canal; L, lateral semicircular canal; P, posterior semicircular canal.

Since the fast phase of nystagmus linear component is directed downwards into head hanging positions, it beats away from the ground being for that apogeotropic.

Basing on nystagmus fast phase direction of the linear component the latter form should be distinguished from the more frequent PSC BPPV variant in which the debris are localized into its ampullary arm: in such a form, nystagmus fast phase direction of the linear component is up beating when head is hanging and for that it is geotropic (G-PSC BPPV).

From 2006 to 2014 we observed over 150 patients sharing the same clinical characteristics and an identical nystagmic pattern with those of the pilot group.

Basing on such a clinical experience we believed useful to pinpoint some aspects regarding both nystagmus and symptoms that are characteristic of A-PSC BPPV.

Moreover, in the present paper, we propose two different physical therapies to cure A-PSC BPPV, that have been tested on 16 patients observed from January to August 2014, and whose preliminary results are also reported. These techniques, if demonstrated effective, could help to differentiate A-PSC BPPV from ASC BPPV of the opposite side.

Clinical aspects

Positional nystagmus

A-PSC BPPV positional nystagmus recognizes some characteristic aspects: i) it is not evoked by a unique provoking positioning: A-PSC positional nystagmus may occur indifferently onto any of the head hanging positions (right and left Dix-Hallpike’s positioning, head-hanging position and enhanced head-hanging position2) or all of them and, sometimes, it can be elicited also onto side lateral positions; ii) it has not latency: that is that it manifests as soon as the evoked position is reached; iii) it has more frequently a simil-paroxysmal rather than a frankly paroxysmal course, which means that the nystagmus is characterized by a crescendo-decrescendo course but it has a lower intensity and a greater duration than usual, and sometimes it is not completely exhaustible, or it is almost stationary; iv) it is mainly vertical-down beating; it has also a slight torsional component indicating the affected PSC. The latter component sometimes lacks making definition of side’s pathology difficult and the diagnosis of its peripheral origin as well; v) it has a variable duration, but A-PSC nystagmus usually lasts more than two minutes, often without ending even maintaining the provoking position; vi) raising up to the upright position A-PSC nystagmus usually does not reverse its direction, rather it sometimes continues maintaining the same direction of that of the head hanging position or, more often, ceases when the sitting position is reached; vii) it does not fatigue repeating positioning.

We tried to give a reasonable explanation for each of these aspects. These are purely theoretical hypothesis with which we tried to explain, on the basis of a mechanical model, a clinical observation, that has proven to be repeatable and reproducible in the same conditions of examination in most patients in our center, and has also been reported by others.7

Point 1: It can be explained because in all of the provoking positions the non-ampullary arm of PSC takes on a downward slope, vertical enough to move the debris in an ampullopetal direction.

Point 2: Given the premise that the otoconial mass is somewhat entrapped into the region next to the common crus, A-PSC nystagmus does not present latency because the debris is not localized in the ampulla, but in a section that is already canal. Actually, Squires et al.8 reported the results of a study on a model of semicircular canal, which was compound to explain the mechanism of canalo- and cupulo-lithiasis: the fundamental concept is that as long as the clot moves in the larger part of the canal, that is the region of the ampulla, it has no effect on the cupula. When the debris enters the actual canal a transcupular pressure is generated, which determines a cupular displacement and nystagmus onset. This effect is maintained since the debris are kept away from canal walls, otherwise they return to have none effect on the ampullary receptor, unless, as is the case of A-PSC BPPV, the clot does completely fill that portion of the canal: in such a circumstance its effect on the cupula is even greater.

Furthermore, being the particles localized into the non-ampullary arm of the PSC, they act as a leaky piston9 (longer than usual because of the distance from the ampulla), as they gravitate through the canal. Taking into account the approximately 1:5 diameter differential between the semicircular canal and the ampulla, and the hydrostatic pressure of the endolymphatic column (being the otoconial mass away from the ampulla), by Pascal’s principle and Stevino’s law, this would produce a mechanical advantage inversely proportional to the ratio of the cross-sectional areas. In other words, these particles would be approximately over 25 times more effective in overcoming cupular resistance, than they would be if they were near the ampulla or attached to the cupula. This way the otoconial drag immediately overcomes the inertia and resistance of the endolymph as well as the elasticity of the cupula, with no latency, in the provoking positioning, as it moves towards the ampulla.

Point 3: Temporal course of A-PSC nystagmus is not frankly paroxysmal maybe because its intensity is generally smaller than that of G-PSC BPPV. It is possible that debris localized into the non-ampullary arm of PSC moves slower with respect to a peri-ampullary mass due the narrower and shorter size of the former tract of the canal, being slowed by the attrition with the canal walls.

Point 4: The characteristic that the vertical component of nystagmus fast phase prevails over the torsional one can be attributed to some anatomical aspects: it is likely that PSC rotates itself proceeding from the ampullary to non ampullary arm, making the latter closer to the sagittal plane. It is for that reason that the linear component of the vector representing the direction of nystagmus, being generated by the part of the canal adjacent to the common crus, is greater than the torsional one.10

Point 5: A-PSC BPPV TVP-DBNy nystagmus has a very long duration or does not end probably because, during head hanging positioning, the otoconial mass moves towards the ampulla: taking advantage of its weight and facilitated by the verticality taken by the portion of the canal in which it is located, it compresses the endolymphatic column below, against the ampullary crest that is deflected towards the utricle. The debris, however, remains partially trapped in that portion of the canal, so that there is not reflux of endolymph, and the column of fluid, still under pressure, continues to press against the receptor. Evidently this causes the ampullary crest to come back to the resting position slower than what it normally happens because of its time constant.

Such debris entrapment could be the same phenomenon of canalith jam hypothesized by Epley9,11 to explain the sudden conversion of transient nystagmus to a rapid form that persists irrespective of head positions he occasionally observed while undertaking the canalith repositioning procedure.

Moreover, as hypothesized by Asprella-Libonati,12 the long duration of the nystagmus could be explained by assuming a balance of forces more or less equal in size and acting in opposite directions on the otolithic mass. In fact, during head hanging positioning, gravity pushes the debris towards the ampulla, while the elastic deformation of the cupula and both the viscosity and the friction of the endolymph oppose the gravitating debris. This balance of forces keeps the otoliths suspended inside the canal and the cupula deflected for a long time.

Point 6: Lacking of reversal of A-PSC positional nystagmus raising up to the sitting position can be explained by the opposite direction of gravity driven forces (the force of gravity directed forwards and the angular acceleration of endolymph directed backwards) on the otoconial mass while it stands in a poorly sloping down tract of the canal. Actually, when located in such a position debris cannot fully take advantage of their weight. Unlike while head hanging, when the otoconial mass produces a compression of the endolymphatic column below, while raising up the debris should act with a suction mechanism, which is probably less effective in itself and because of the great distance from the receptor.

Another possible explanation of the lack of reversal of A-PSC positional nystagmus could be that during the laying down positioning, the otoconial mass initially moves slightly forward, toward the common crus (pushed by the endolymph), and when the head hanging position is reached the clot moves toward the ampulla (attracted by gravity), coming back to its original position (the latter movement is the one that generates the torsional-down beating nystagmus). This could be the reason why when patient returns in sitting position the debris no longer moves, being already in its original position, thus not generating any nystagmus.

The lack of reversal of the nystagmus could also be explained by the canalith jam model suggested by Epley9,11 if we admit the possibility of a partial or transient jam. In this case we could observe a persistent nystagmus in head hanging position, due to a canaliths jam that completely occludes the canal; when the patient is brought back to the sitting position the debris becomes less tight, resulting in a partial jam, so that the nystagmus disappears without reversing.

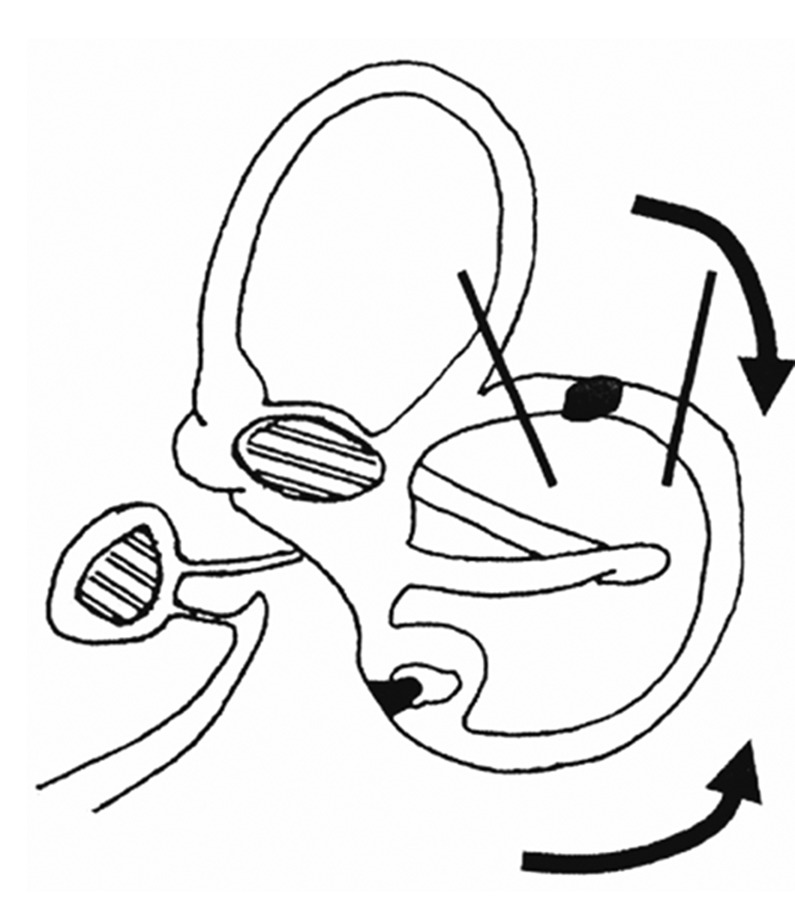

Point 7: It is possible that nystagmus does not fatigue because of the poor dispersion of otoconia induced by repeated positioning while they are entrapped in a very tight portion of the PSC (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The nystagmus does not fatigue to repeated positionings. Curved arrows: movements of posterior semicircular canal (PSC) during positionings (head hanging positionings and coming back to sitting position). Straight lines: portion of the PSC in which the debris is trapped.

Symptoms

Onset of A-PSC BPPV is often similar to that of G-PSC BPPV both regarding the intensity of positional vertigo and its modality of presentation. Thus, vertigo usually manifests getting out of bed in the morning or during the night, sometimes also performing other movements on the plane of vertical semicircular canals. In effect, it is likely that debris, once entered the common crus, initially reaches the ampullary arm of PSC, giving rise to typical vertigo during vertical positioning.

Later, but sometimes since the beginning, rotational vertigo can be lighter with respect the one reported by patients suffering from G-PSC BPPV; actually, subjects with A-PSC BPPV complain, as a main symptom, a marked sense of dizziness rather than a true rotational vertigo, still enhanced with change of positions but, overall, continuous.

Dizziness can be generated by a clot of debris that comes entrapped into the canal lumen rather than a mass freely moving to and fro into it. On the other hand, location of debris into the tract of PSC near to the common crus makes it very unstable thus generating into patients a continuous, uncomfortable sense of instability.

As a whole, patients suffering from A-PSC BPPV feel worse than those with G-PSC BPPV because symptoms are positioning vertigo added with a continuous non-positional dizziness: these complaints also give rise to a marked neuro-vegetative symptomatology, even more annoying and troublesome than those generated by G-PSC BPPV.

For A-PSC BPPV, vertigo triggered by repeated vertical positioning is longer than that typical of G-PSC BPPV, often not exhausted by the maintaining of the reached head hanging position. The longer duration of vertigo is related to the longer duration of nystagmus (see above).

Despite of the usual lack of nystagmus when raising up (torsional vertical positional down beating nystagmus almost always does not reverse in the sitting position, rather it often continues beating in the same direction for a while) subjective sensation of vertigo in patients with A-PSC BPPV is stronger when patient moves from the supine to the upright position than laying down.

The explanation of the enhanced subjective symptom can be found exactly in the fact that this movement is done when positional nystagmus is still present.

Finally, A-PSC BPPV hardly resolve, when compared with G-PSC BPPV, either spontaneously or by means of therapeutic maneuvers. It is probable that, to remain in such a uncomfortable standing, the debris could be somehow trapped in that part of the canal and that it will also find more difficult to get out, either spontaneously or driven by liberatory or repositioning maneuvers.

Therapeutic proposal

Having in mind the possible pathogenetic mechanism and the theoretical position of debris into PSC we recently devised some physical single treatment approach techniques to cure A-PSC BPPV.

In analogy with the most successfully physical treatment used for BPPV due to other semicircular canals involvement, also therapeutic procedures for A-PSC BPPV must use a brisk deceleration or a setting mechanism to obtain the discharge of the otoconial debris from the canal lumen.

We thought, therefore, to a liberatory maneuver that we named demi Semont and to a forced prolonged position that we called as 45° forced prolonged position (45° FPP).

Demi Semont maneuver

We used the term demi Semont to describe this kind of procedure because it represents, in effect, the second part of the well-known modified Semont’s maneuver.13

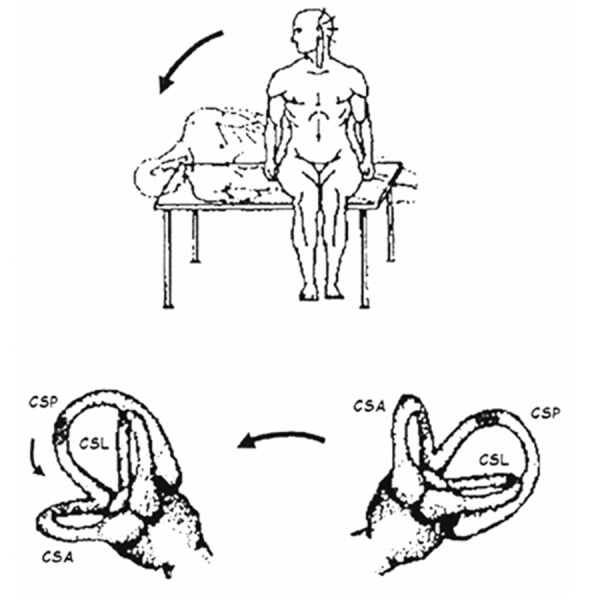

Figure 3 shows a schematic representation of the maneuver in the case of a left A-PSC BPPV.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of demi Semont maneuver for a left apogeotropic variant posterior semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (see the text for details). CSP, posterior semicircular canal; CSA, anterior semicircular canal; CSL, lateral semicircular canal.

The sequence of movements is the following: i) patients is seated in front of the examiner having the legs out of the bed; ii) patient’s head is turned by 45° to the right (healthy) side, to put the left PSC onto the frontal plane; iii) patient is brought onto the right (healthy) side. It is better to move the subject not too briskly, in order to avoid an excessive ampullopetal endolymphatic flow that would push the debris towards the ampullary arm of the canal, but using a final sharp deceleration to the head in order to take advantage of the inertia of otoconia and move it towards the common crus, so that it can enter the utricle. The examiner looks for the possible appearance of a liberatory nystagmus, which should have, as a whole, a direction opposite to that of nystagmus detected onto head hanging positioning (in our case, clockwise and up beating). On the other hand, sometimes, onto the same position, torsional-down beating nystagmus can be detected. Such an ocular movement can be induced by the debris transition through the last portion of the common crus thus generating a prevailing ampullofugal flow into the ASC of the same side; iv) after 20-30 s, without changing the head position, patient is brought back to the sitting position, now quickly enough to facilitate motion of debris eventually remained into the canal towards the utricle, under the pressure of the endolymph; v) in addition, the examiner impresses a final backwards bending to the head of the patient in order to promote the fall into the utricle of any debris still remaining in the canal; vi) the entire sequence of movements is repeated 5 times; vii) patient is asked to respect the same restrictions as for G-PSC BPPV.

This kind of procedure needs the affected side to be identified. For this aim, the torsional component of positioning nystagmus must be clearly detected: clockwise and counterclockwise torsional fast phases will indicate right and left PSC, respectively.

45° forced prolonged position technique

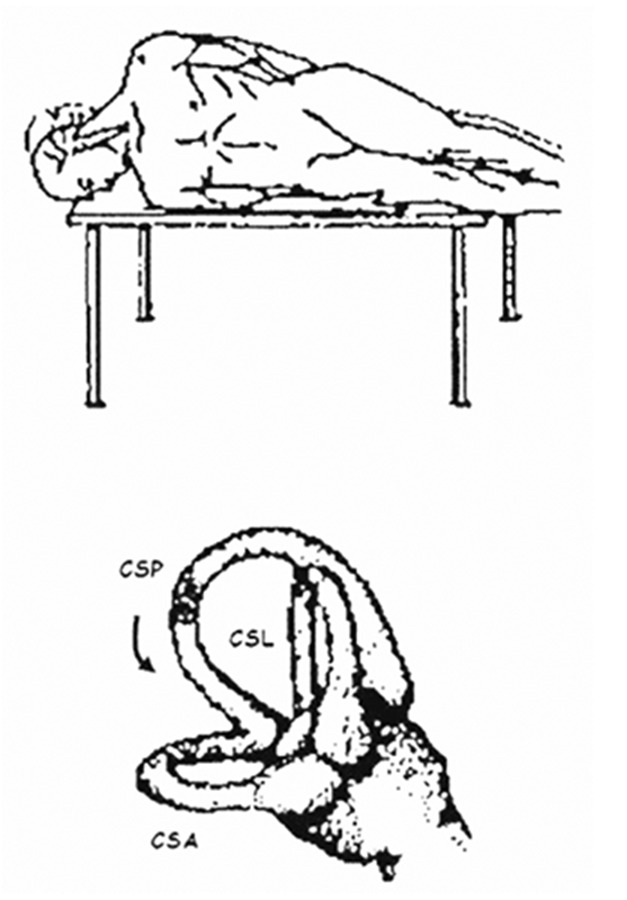

We named this technique 45° FPP because it is similar to the FPP procedure described for LSC BPPV.14 The gravity force is exploited in order to move the clot towards the utricle by simply arranging the PSC in a high with the opening of its non-ampullary arm looking downwards. In Figure 4 it is shown a schematic representation of the technique in the case of a left A-PSC BPPV: i) patient is asked to lay on the right (healthy) side with the head turned by 45° downwards; ii) patient should remain in this position for at least 8 hours. Such a prolonged position could be completed only at home.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of 45° FPP technique for a left apogeotropic variant posterior semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (see the text for details). CSP, posterior semicircular canal; CSA, anterior semicircular canal; CSL, lateral semicircular canal.

Also for 45° FPP is necessary to identify the affected side in order to properly suggest the right positioning side.

Both the techniques described above aim to cure A-PSC BPPV specifically. If effective, they will allow to ensure to differentiate A-PSC BPPV from ASC BPPV of the opposite side, with which it shares the same TVP-DBNy.

Epley’s reverted procedure15 could be also suitable to treat A-PSC BPPV but it is theoretically adequate for ASC BPPV of the opposite side too, making the differential diagnosis more difficult.

Preliminary therapeutic outcomes

In a period that goes from January to August 2014 we submitted to the previously described physical therapies 16 patients presenting to our clinic for positional vertigo and showing a TVP-DBNy of peripheral origin. Four of them had a history of a previously detected G-PSC BPPV.

Ten patients had a possible right A-PSC BPPV (clockwise TVP-DBNy) and six of them were diagnosed as probably affected by a left A-PSC BPPV (counterclockwise TVP-DBNy).

Eleven subjects underwent the demi Semont technique and the remaining five were asked to perform the 45° FPP at home.

Control visit was programmed three days after the therapy, at most.

To that time, the outcome of therapy was successful in 11 patients out of 16 (68.7%). Therapy has been considered successfully both when patients were sign free and when they transformed apogeotropic TVP-DBNy into a geotropic paroxysmal positional nystagmus.

The demi Semont revealed effective in 8 subjects out of 11 and the 45° FPP had a positive outcome in 3 patients of 5.

At the control visit, into the group treated with the demi Semont, 5 subjects were cured and 3 patients had a G-PSC BPPV; among subjects treated with 45° FPP 1 patient was sign free and 2 had a G-PSC BPPV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Preliminary results of physical therapy.

| Treated patients | Successful therapy | Cured | Transformed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 16 | 11 | 6 | 5 |

| Demi Semont | 11 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| 45° FPP | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

45° FPP, 45° forced prolonged position technique.

Only 1 of the patients showing a G-PSC BPPV after therapy had also a previous G-BPPV in his history.

Conclusions

We recently reported that besides ASC BPPV also PSC BPPV can manifest with a TVP-DBNy (A-PSC BPPV).1

Unfortunately the two pathologies cannot be distinguished on the basis of this characterizing sign; a reliable differential diagnosis can be made, at present, only by observing the behavior of signs in the course of time. With the experience made with 6 pilot cases described in a previous paper and over 150 similar cases collected in the past seven years for whom we finally diagnosed A-PSC BPPV, we describe, in the present paper, some clinical aspects of A-PSC BPPV that could help to distinguish this BPPV variant. For each symptoms and nystagmus characteristics we tried to give an explanation on the basis of the hypothesized pathogenetic mechanism. Moreover we developed two techniques of physical therapy theoretically specific for A-PSC BPPV. If effective in resolving TVP-DBNy or in transforming it into a nystagmus typical of G-PSC BPPV they would allow to ensure diagnosis. Preliminary results of these techniques are satisfying because successful in 68% of cases. Additional cases are needed in the future to allow statistically significant results as well as a comparison with other physical therapies to decide the best therapeutic approach.

References

- 1.Vannucchi P, Pecci R, Giannoni B. Posterior semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo presenting with torsional downbeating nystagmus: an apogeotropic variant. Int J Otolaryngol 2012;2012: 413603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertholon P, Bronstein AM, Davies RA, Rudge P, Thilo KV. Positional down beating nystagmus in 50 patients: cerebellar disorders and possible anterior semicircular canalithiasis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:366-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt T, Steddin S. Current view of the mechanism of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: cupulolithiasis or canalithiasis? J Vestib Res 1993;3:373-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epley JM. New dimensions of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1980;88:599-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall SF, Ruby RRF, McClure JA. The mechanics of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1979;8:151-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uemura T, Cohen B. Effects of vestibular nuclei lesions on vestibulo-ocular reflexes and posture in monkeys. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1973;315:5-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asprella-Libonati G. Practical management of BPPV: diagnosis and therapy. Proc. AAO-HNSF 2012 - American Academy of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 2012. September 9-12, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Squires TM, Weidman MS, Hain TC, Stone HA. A mathematical model for top-shelf vertigo: the role of sedimenting otoconia in BPPV. J Biomech 2004;37:1137-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epley JM. Positional vertigo related to semicircular canalithiasis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;112:154-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanebayashi H, Suzuki M, Ogawa K. Measurement of helical angle of the human semicircular canals using rapid-prototyped inner ear model. Equilibrium Res 2008;67:294-300. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epley JM. Human experience with canalith repositioning maneuvers. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001;942:179-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asprella-Libonati G. Lateral canal BPPV with pseudo-spontaneous nystagmus masquerading as vestibular neuritis in acute vertigo: a series of 273 cases. J Vestib Res 2014;24:343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandalà M, Santoro GP, Asprella Libonati G, Casani AP, Faralli M, Giannoni B, et al. Double-blind randomized trial on short-term efficacy of the Semont maneuver for the treatment of posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol 2012;259:882-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vannucchi P, Giannoni B, Pagnini P. Treatment of horizontal semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Vestib Res 1997;7:1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honrubia V, Baloh RW, Harris MR, Jacobson KM. Paroxysmal positional vertigo syndrome. Am J Otol 1999;20:465-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]