NAL-NL2 is the second generation of prescription procedures from The National Acoustic Laboratories (NAL) for fitting wide dynamic range compression (WDRC) instruments. Like its predecessor NAL-NL1 (Dillon, 1999), NAL-NL2 aims at making speech intelligible and overall loudness comfortable. This aim is mainly driven by a belief that these factors are most important for hearing aid users, but is also driven by the fact that less information is available about how to adjust gain to optimise other parameters that affect prescription such as localisation, tonal quality, detection of environmental sounds, and naturalness. In both formulas, the objective is achieved by combining a speech intelligibility model and a loudness model in an adaptive computer-controlled optimisation process. Adjustments have further been made to the theoretical component of NAL-NL2 that are directed by empirical data collected during the past decade with NAL-NL1. In this paper, the data underlying NAL-NL2 and the derivation procedure are presented, and the main differences from NAL-NL1 are outlined.

The optimisation procedure

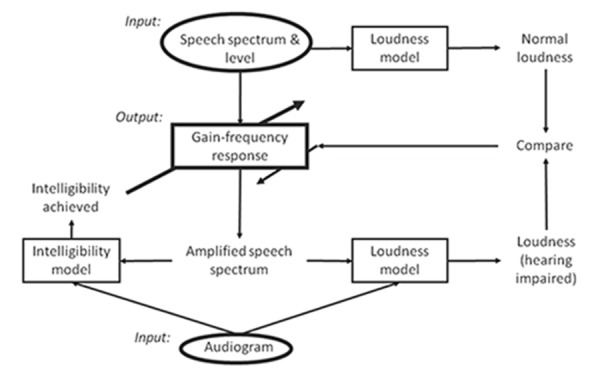

A schematic overview of the adaptive optimisation procedure is shown in Figure 1. The two inputs to the process are the input speech spectrum and level, and the audiogram for which a prescription is required. The output is the prescription expressed as a gain-frequency response. The two input parameters are entered into two feedback loops, which operate in tandem to optimise the gain-frequency response. One loop uses an intelligibility model to find the gain-frequency response that maximises speech intelligibility. If left unchecked, this loop would produce the same output level irrespective of the input level of speech, a result that would not give the hearing aid wearer an acceptable representation of the auditory world. The second loop therefore uses a loudness model (Moore & Glasberg, 1997; 2004) to calculate the loudness that would be perceived by the hearing-impaired person with the selected gain-frequency response. The calculated loudness is compared to the loudness that would be perceived by a normal-hearing person listening to the same input speech spectrum and level. If loudness calculated for the audiogram exceeds the normal-hearing loudness, the overall gain is decreased. The adaptive process was used to derive the optimal gain-frequency responses for 240 audiograms, covering a wide range of severity and slopes, each at seven speech input levels from 40 to 100 dB SPL. Using a neural network, the optimised gain values from all the audiograms and all the input levels were drawn together into a single composite prescription formula.

Figure 1.

The adaptive optimisation process. See text for further explanation.

The theoretical derivation of NAL-NL2 differed from that of NAL-NL1 on two points. First, the intelligibility model, which is a revised version of the speech intelligibility index (SII) formula (ANSI, 1997), was updated. The difference between the original SII formula and the speech intelligibility model used to derive NAL-NL1 and NAL-NL2 is in the audibility factor. In the original SII formula the audibility factor assumes that, irrespective of the degree of hearing loss, speech is fully understood when all speech components are audible.

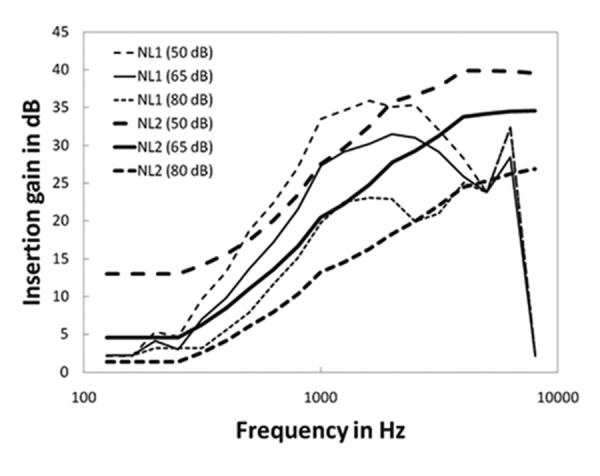

In the speech intelligibility model used in the optimisation procedure, an effective audibility factor has been introduced, which takes into account that as the hearing loss gets more severe, less information is extracted from the speech signal, even when it is audible above threshold. The effective audibility factor was based on data collected at NAL prior to deriving NAL-NL1 (Ching, et al., 1998). The further revision made to the speech intelligibility model before deriving NAL-NL2 was based on more extensive data collected on 70 adults on how much information people with hearing loss can extract from speech once it has been made audible. Data were collected both in quiet and in noise and resulted in a new effective audibility factor. Second, constraints to the selected gain were applied such that no compression was introduced for speech presented below 50 dB SPL, and no gain was prescribed at frequencies below 50 Hz and above 16 kHz. The latter constraints ensured a smoother gain-frequency response between the two anchor points. These changes have resulted in NAL-NL2 prescribing a different gain-frequency response slope to NAL-NL1. Generally, NAL-NL2 prescribes relatively more gain across low and high frequencies and less gain across mid frequencies than NAL-NL1, see Figure 2. In the speech intelligibility model, an importance function is used to ensure that sufficient gain is applied at the frequencies that are most important for speech understanding. Low frequencies are more important in tonal languages, which are most common across Asia and Africa, than in non-tonal languages. Therefore, when deriving NAL-NL2, the optimisation procedure was run twice using different importance functions in the speech intelligibility model to derive gain for the two types of languages. As a result there are two versions of NAL-NL2, and slightly more gain is prescribed across the low frequencies for tonal than for non-tonal languages.

Figure 2.

For a gently sloping hearing loss the NAL-NL1 (thin lines) and NAL-NL2 (heavy lines) targets are shown for three input levels (50, 65, and 80 dB SPL).

Adjustments to optimised data

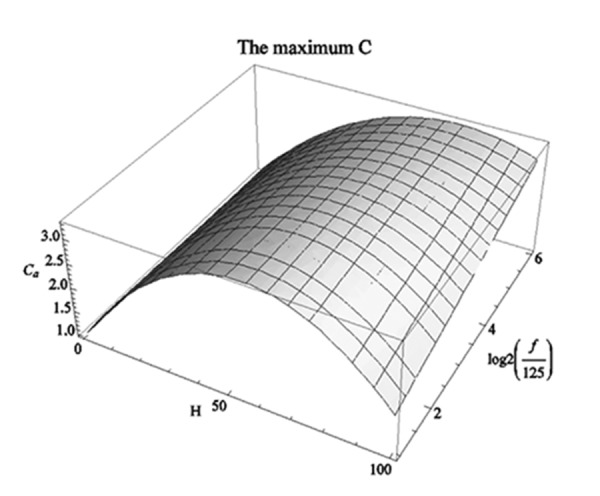

Before deriving the theoretical NAL-NL2 formula, constraints were further applied to the optimised gain values such that the compression ratio for a given frequency and degree of hearing loss could not exceed a maximum value, selected to avoid any detrimental effect on speech understanding. Data have suggested that hearing aid users with severe or profound hearing loss prefer lower compression ratios than prescribed by NAL-NL1, when fitted with fast-acting compression (Keidser, et al., 2007). As demonstrated in Figure 3, the study participants selected lower compression ratios across the low than high frequencies, presumably to obtain a better preservation of both the speech envelope and the prosodic cues.

Figure 3.

The maximum compression ratios (C) accepted with fast-acting compression as a function of degree of hearing loss (H) and frequency (f).

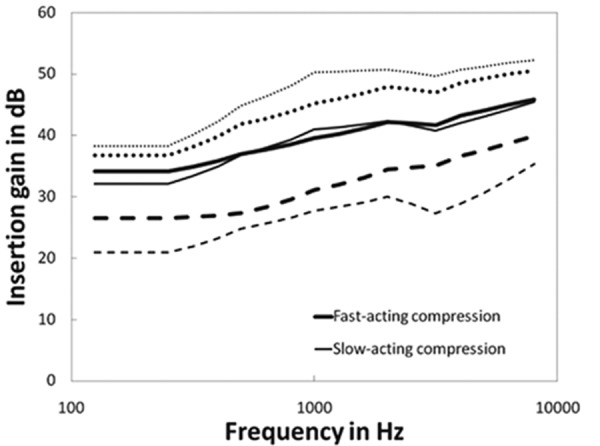

There is, however, no reasons to believe that this population could not benefit from higher compression ratios, which would provide audibility of a wider range of input levels, when listening with slow-acting compression. Consequently, two sets of limits were applied to the optimised gain data, and as a result NAL-NL1 will prescribe higher compression ratios to people with a severe or profound hearing loss if they are fitted with slow-acting compression than when fitted with fast-acting compression, see Figure 4. Compression speed has no real effect on the compression ratio prescribed to hearing aid users with milder hearing loss.

Figure 4.

The NAL-NL2 targets prescribed for the input levels of 80, 65, and 50 dB SPL for a flat 80 dB HL hearing loss when fitted with fast-acting (heavy lines) and slow-acting (thin lines) compression.

Adjustments to overall gain

Many experiments in which NAL-NL1 has been used as baseline response have provided empirical data that suggest how much gain hearing aid users with different profiles prefer. For example, the realear insertion gain measurements of the fine-tuned, or preferred, response for a 65 dB input level by 187 adults who have participated in various research projects were analysed. The analysis revealed that female hearing aid users, irrespective of degree of hearing loss and experience with amplification preferred less gain (2 dB, on average) than male hearing aid users (Keidser & Dillon, 2006). The difference in preferred gain was statistically significant (P<0.05). Consequently, NAL-NL2 prescribes gender specific gain.

The same data set showed that when the hearing loss was mild there was no difference in overall gain preferred by new and experienced hearing aid users. However, when the hearing loss became moderate, new hearing aid users preferred significantly less gain than experienced hearing aid users. In fact, progressively less gain was preferred by new users as the degree of hearing loss increased (Keidser, et al., 2008). Data collected for a small sample suggested that, on average, new hearing aid users with moderate hearing loss adapted to gain levels preferred by experienced hearing aid users with a similar degree of hearing loss over a period of about two years. On this background, NAL-NL2 recommends gain adaptation for new hearing aid users with more than a mild hearing loss.

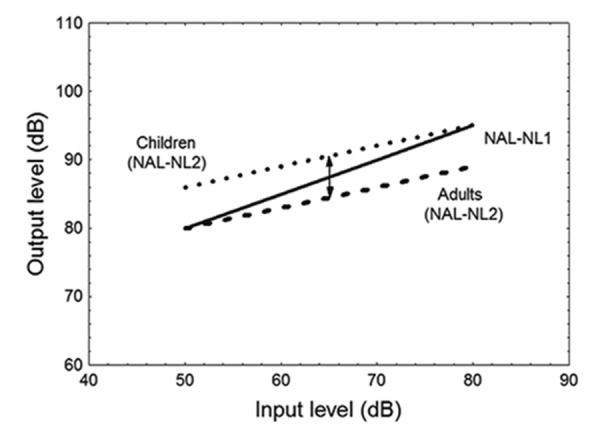

From the same data set, it could also be concluded that adults with mild and moderate hearing loss generally preferred less overall gain (3 dB, on average) than prescribed by NAL-NL1 for a 65 dB SPL input. At least two studies have further demonstrated that hearing aid users with mild or moderate hearing loss preferred a relatively higher gain reduction for higher input levels (80 dB SPL) but a relatively smaller gain reduction for lower input levels (50 dB SPL), which means that the adults preferred a slightly higher compression ratio than prescribed by NAL-NL1 (Smeds, et al., 2006; Zakis, et al., 2007), see Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A schematic overview of the changes to the overall output level prescribed by NAL-NL2 relative to NAL-NL1 across different input levels for children (dotted line) and adults (broken line).

In contrast, a study on children suggested that the younger population preferred higher gain than adults (Scollie, et al., 2010). An increase in gain is more likely to lead to greater speech intelligibility at low input levels where speech is most limited by audibility, and is less likely to cause noise-induced hearing loss for low input levels than for high input levels. Therefore, gain is for children increased for low input levels with a progressive decrease in increased gain with increased input level (Figure 5). That is, NAL-NL2 also prescribes a relatively higher compression ratio for children with mild or moderate hearing loss than do NAL-NL1.

Conclusions

NAL-NL2 is a revised version of NAL-NL1. The revisions are based on extensive empirical data. In comparison to NAL-NL1, NAL-NL2 prescribes a different gain-frequency response shape, and slightly higher compression ratios are prescribed for those with mild or moderate hearing loss. NAL-NL2 further takes the profile of the hearing aid user (age, gender, and experience), language, and compressor speed into consideration.

References

- American National Standards Institute. 1997. Methods for calculation of the speech intelligibility index. ANSI S35-1997. Acoustical Society of America, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Ching T.Y.C., Dillon H., Byrne D. 1998. Speech recognition of hearing-impaired listeners: Predictions from audibility and the limited role of high frequency amplification. J Acoust Soc Am 103(2), 1128-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon H. 1999. Page Ten: NAL-NL1: A new procedure for fitting non-linear hearing aids. Hear J 52, 10-16. [Google Scholar]

- Keidser G., Dillon H. 2006. What’s new in prescriptive fittings Down Under? Palmer C.V., Seewald R. (Eds.), Hearing Care for Adults 2006. Phonak AG, Stafa, Switzerland, pp. 133-142. [Google Scholar]

- Keidser G., Dillon H., Dyrlund O., Carter L., Hartley D. 2007. Preferred low- and high-frequency compression ratios among hearing aid users with moderately severe to profound hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol 18(1), 17-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keidser G., O’Brien A., Carter L., McLelland M., Yeend I. 2008. Variation in preferred gain with experience for hearing aid users. Int J Audiol 47(10), 621-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B.C.J., Glasberg B.R. 1997. A model of loudness perception applied to cochlear hearing loss. Aud Neurosci 3, 289-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B.C.J., Glasberg B.R. 2004. A revised model of loudness perception applied to cochlear hearing loss. Hear Res 188, 70-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollie S., Ching T., Seewald R., Dillon H., Britton L., Steinberg J., Corcoran J. 2010. Evaluation of the NAL-NL1 and DSL v4.1 prescriptions for children: Preference in real world use. Int J Audiol 49, S49-S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeds K., Keidser G., Zakis J., Dillon H., Leijon A., Grant F., Convery E., Brew C. 2006. Preferred overall loudness. II: Listening through hearing aids in field and laboratory tests. Int J Audiol 45(1), 12-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakis J.A., Dillon H., McDermott H.J. 2007. The design and evaluation of a hearing aid with trainable amplification parameters. Ear Hear 28(6), 812-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]