Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy intravenous (IV) ondansetron with ketamine plus midazolam for the prevention of shivering during spinal anesthesia (SA).

Materials and Methods:

Ninety patients, aged 18–65 years, undergoing lower extremity orthopedic surgery were included in the present study. SA was performed in all patients with hyperbaric bupivacaine 15 mg. The patients were randomly allocated to receive normal saline (Group C), ondansetron 8 mg IV (Group O) or ketamine 0.25 mg/kg IV plus midazolam 37.5 μg/kg IV (Group KM) immediately after SA. During surgery, shivering scores were recorded at 5 min intervals. The operating room temperature was maintained at 24°C.

Results:

The incidences of shivering were 18 (60%) in Group C, 6 (20%) in Group KM and 8 (26.6%) in Group O. The difference between Groups O and Group KM with Group C was statistically significant (P < 0.05). No significant difference was noted between Groups KM with Group O in this regard (P > 0.05). Peripheral and core temperature changes throughout surgery were not significantly different among three groups (P > 0.05). Incidence (%) of hallucination was not significantly different between the three groups (0, 3.3, 0 in Group O, Group KM, Group C respectively, P > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Prophylactic use of ondansetron 8 mg IV was comparable to ketamine 0.25 mg/kg IV plus midazolam 37.5 μg/kg IV in preventing shivering during SA.

Keywords: Ketamine, midazolam, ondansetron, shivering, spinal anesthesia, thermoregulation

INTRODUCTION

Spinal anesthesia (SA) impairs thermoregulatory control of the body.[1] It was shown that SA increases the incidence of shivering up to 56.7%.[2] Shivering during SA has potentially detrimental effects such as increases in carbon dioxide production, cardiac work, oxygen consumption, lung ventilation, and consequently decrease in mixed venous oxygen saturation.[3] In addition, shivering has been shown to increase the metabolic rate by up to 500% of basic.[4]

Spinal anesthesia increases peripheral vasodilatation that consequently causes redistribution of heat from core to the periphery.[5,6] Ketamine causes central sympathetic stimulation and inhibition of norepinephrine uptake in postganglionic sympathetic nerve endings. Due to ketamine's sympathetic stimulation and vasoconstriction, it can decrease core-to-peripheral redistribution of heat.[7] Previous studies showed that using ketamine 0.5 mg/kg/iv as prophylaxis was effective in preventing shivering during SA.[8]

Between benzodiazepines, diazepam and midazolam have been shown to be effective in prevention of postoperative shivering without causing impairment in thermoregulatory control of the body.[9,10]

Honarmand and Safavi[11] showed that prophylactic use of ketamine 0.25 mg/kg IV combined with midazolam 37.5 μg/kg iv was more effective than using ketamine 0.5 mg/kg iv or midazolam 75 μg/kg iv singly in preventing shivering during SA.

Ondansetron is a 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3) antagonist that had anti-shivering effect on patients undergoing surgery with general anesthesia.[12,13,14] Kelsaka et al.[15] showed that ondansetron 8 mg intravenously administered immediately before SA had antishivering effects. There was no previous study that compares the antishivering effect of ondansetron with combination of midazolam-ketamine during SA. So, this prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study was designed to compare efficacy of using intravenous (IV) ondansetron 8 mg with combined use of ketamine 0.25 mg/kg IV and midazolam 37.5 μg/kg iv in prevention of shivering during SA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining institutional approval from Ethic Committee of our university and taking written informed consent from patients, 90 American Society of Anesthesiologists I to II patients, aged 18–65 years, who were candidate for elective orthopedic surgery with SA were included in this study. The other inclusion criteria were patients who had no psychological disorder, cardiopulmonary disease, hypo- or hyper-thyroidism, initial body temperature > 38.0°C or < 36°C. Also, patients without known history of alcohol, substance abuse or history of receiving vasodilators or similar medications likely to alter thermoregulation were included in the present study. If there was any change in technique of anesthesia or severe bleeding that needed to blood transfusion, the patient was excluded from the study. No premedication was given to the patients. After patient's arrival to the operating room, 10 mL/kg lactated Ringer's solution warmed to 37°C was infused before SA. The infusion rate was then decreased to 6 mL/kg/h. IV fluids were preheated in a warm cabinet.

Heart rate, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and peripheral oxygen saturation were monitored before intrathecal injection and then after at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 min using standard noninvasive monitors. The peripheral and core temperature were recorded with using axillary and ear thermometer (OMRON Medizintechnik GmbH Windeckstr, Mannheim Germany) before intrathecal injection and at 10 min intervals during surgery. The operating room temperature was maintained at 24°C with using a wall thermometer.

Spinal anesthesia was performed at level of either L3/4 or L4/5 interspaces. Hyperbaric bupivacaine 15 mg was injected using a 22-G Quincke spinal needle. The patients were randomly divided in three groups to receive IV normal saline (Group C, n = 30), ondansetron 8 mg IV (Group O, n = 30) or ketamine 0.25 mg/kg + midazolam 37.5 μg/kg (Group KM, n = 30) immediately after SA. The selection of dosage of study drugs was based on a previous study.[11]

The study drugs were diluted to a volume of 4 mL and coded by an anesthesiologist who was blinded to the group allocation. All patients received supplemental oxygen (6 L/min) via nasal cannula throughout the operation. After SA and before beginning of operation, all patients were covered with one layer of surgical drapes over the calves, thighs, and chest and finally one cotton blanket over the entire body.

Sensory block was assessed with a pinprick test at 5 min intervals during the preoperative period. The incidence of shivering was evaluated using a scale as: 0 = not shivering, 1 = piloerection or peripheral vasoconstriction but no visible shivering, 2 = muscular activity in only one muscle group, 3 = muscular activity in more than one muscle group but not generalized, and 4 = shivering involving the whole body.[16]

Shivering score was recorded at 5 min intervals by a physician who was blinded to the study group allocation. If patients had shivering grade 3 or 4 15 min after study drug administration, prophylaxis was considered ineffective, and meperidine 25 mg IV was administered and its dosage was recorded.

The side effects of study drug administration such as hypotension (decrease in MAP more than 20% from baseline), nausea, vomiting, and hallucinations were also recorded. Hypotension was treated by infusion of crystalloid fluids and if necessary ephedrine 5 mg intravenously. The dosage of ephedrine administered in each group was recorded. If nausea and vomiting were development after SA, metoclopramide 10 mg IV was administered. Hallucination was defined as a false sensory experience where the patients reported them see, heard, smelled, tasted and felt something that did not exist.

The degree of sedation was evaluated as: 1 = fully awake and oriented; 2 = drowsy; 3 = eyes closed but rousable to command; 4 = eyes closed but rousable to mild physical stimulation; and 5 = eyes closed but unrousable to mild physical stimulation.[17]

We calculated that 30 patients were required in each group with α = 0.05 and β = 80% if we considered a difference of 40% in the incidence of shivering between control and treated groups. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 17 (Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables including hemodynamic data and temperature values were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc testing. One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's correction was used to analyze differences among the groups. Nominal data were analyzed and compared using the Chi-square test. Sedation levels between three groups were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

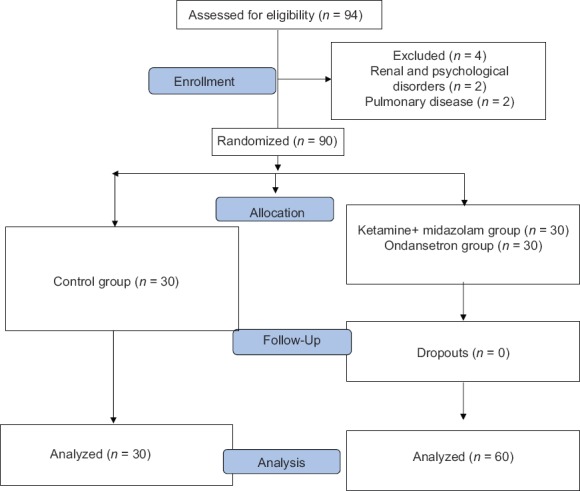

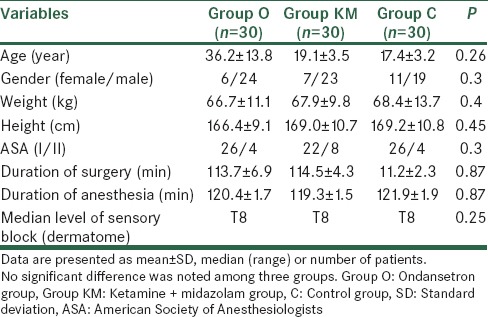

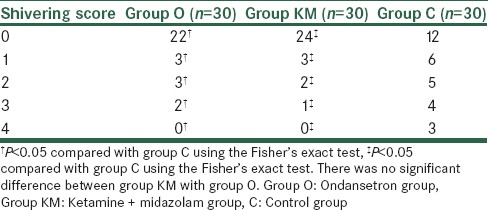

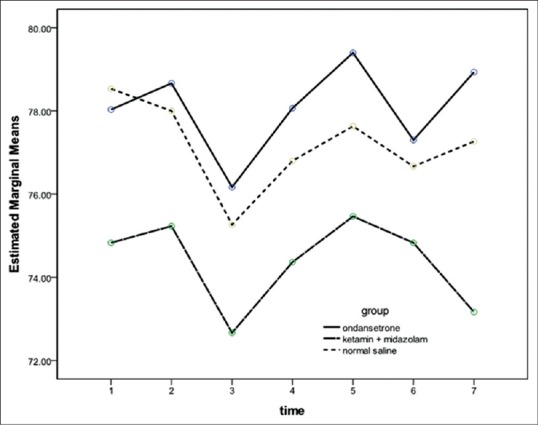

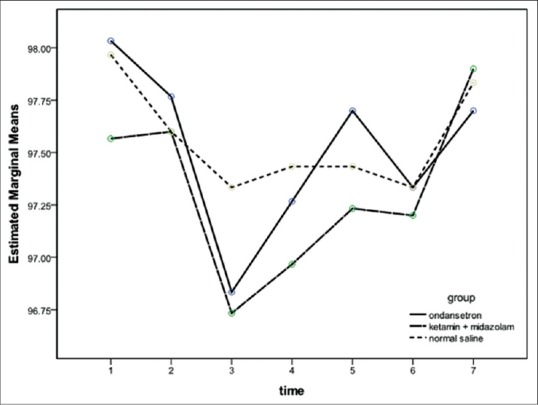

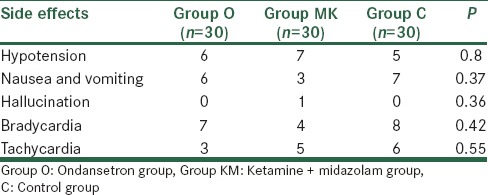

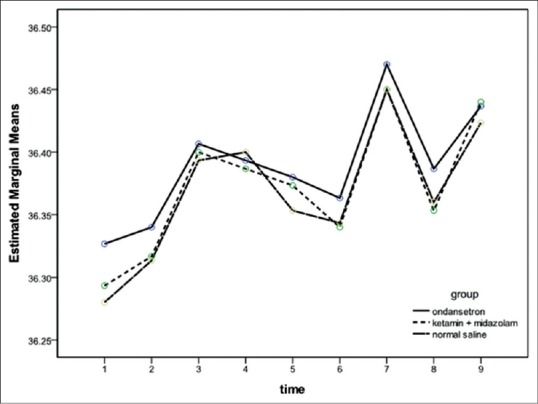

Ninety patients were enrolled in this study. Four patients were excluded due to renal and psychological disorder, and two patients were excluded due to pulmonary disease [Figure 1]. Demographic data of patients, the median level of sensory block and duration of surgery and anesthesia were similar among the groups [Table 1]. After 15 min of spinal analgesia, shivering at Grade 4 was not observed in any patient in Group O and Group KM while three patients in Group C had shivering with Grade 4 (P < 0.05) [Table 2]. The numbers of patients experienced shivering at grade 0–4 was significantly higher in Group C compared with Groups O and Group KM (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between Groups O with Group KM in this regards (P > 0.05) [Table 2]. Sedation scores were not significantly different between three groups (P > 0.05). Hemodynamic values were not significantly different between three groups throughout the study [Figures 2 and 3]. The incidence of hallucination, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, and tachycardia were not significantly different between the three groups (P > 0.05) [Table 3]. There was no significant difference in core temperature changes among three groups (P > 0.05) [Figure 4].

Figure 1.

Randomized patient

Table 1.

Demographic data

Table 2.

Incidence of shivering in three groups

Figure 2.

Mean arterial pressure changes in three groups. There was no significant difference between the groups. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation Group O = Ondansetron group; Group KM = Ketamine + midazolam group; C = Control group

Figure 3.

Peripheral oxygen saturation changes in three groups. There was no significant difference between the groups. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation Group O = Ondansetron group; Group KM = Ketamine + midazolam group; C = Control group

Table 3.

Incidence of hypotension, nausea, vomiting, hallucination, bradycardia and tachycardia among the three groups

Figure 4.

Change in core temperature with time in three groups. There was no significant between three groups. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation Group O = Ondansetron group; Group KM = Ketamine + midazolam group; C = Control group

DISCUSSION

In this study, it was shown that prophylactic use of ondansetron 8 mg IV was comparable to ketamine 0.25 mg/kg IV + midazolam 37.5 μg/kg IV in preventing shivering developed during SA. In regional anesthesia, it has been reported that shivering develops in up to 56.7% of all patients (2). In our study, the incidence of shivering were 60% in Group C, 20% in Group KM and 26.6% in Group O. Shivering increases metabolic activity and oxygen consumption and consequently may cause lactic acidosis and arterial hypoxia. In addition, postanesthetic shivering (PAS) may interfere with the monitoring of an electrocardiogram.[16] These all make the prevention of shivering important especially in elderly patients with a low cardiopulmonary reserve.[16] As shivering is a response to hypothermia, body temperature of the patient should be normally maintained within limits of 36.5°C–37.5°C.[18,19,20]

There are three reasons for developing hypothermia under SA. First, SA leads to an internal redistribution of heat from the core to the peripheral compartment.[21] Redistribution of core temperature during regional anesthesia is typically restricted to the lower extremity.[17] Second, with loss of thermoregulatory vasoconstriction below the level of the spinal blockade, there is increased heat loss from body surfaces of the patient. Last, there is altered thermoregulation under SA characterized by a 0.5°C decrease in vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds and a slight increase in the sweating threshold.[1]

Kurz et al.[10] studied SA in young female volunteers, and reported decreases in shivering thresholds of ~0.5°C at sentient skin temperatures near 35°C by spinal blocks to ~T10. Ketamine, which is a competitive receptor antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) has a role in thermoregulation in various levels of the patient. The NMDA receptors modulate the noradrenergic and serotoninergic neurons in the locus coeruleus and consequently the NMDA receptors in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord provide the transmission of the ascending nociceptive stimuli.[22] Ketamine causes sympathetic stimulus and vasoconstriction in patients with the risk of hypothermia. Ketamine probably controls shivering of the patient by nonshivering thermogenesis either influencing the hypothalamus or by the beta-adrenergic effect of norepinephrine.[23]

Ketamine was shown to prevent shivering without hemodynamic alterations in patients undergoing regional anesthesia.[23] Kinoshita et al.[24] study showed that during spinal anesthesia, infusion of low-dose ketamine prevents the decreases in the body temperature in patients sedated with propofol.

It was clear from our data that the combination of ketamine and midazolam prevented the hypothermia in comparison with control group. It is probable that ketamine prevented the arteriovenous shunt vasodilation normally induced by midazolam. Since these shunts are completely under sympathetic control,[25] it seems safe to conclude that ketamine acted centrally to inhibit the effect of midazolam.

The gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAergic) neurons via virtue of GABA mediate the presynaptic inhibition suppressing signals from muscle and cutaneous receptors. Benzodiazepines have been found to reduce repetitive firing in response to depolarizing pulses in mouse spinal cord neurons.[26] Such inhibitory function of midazolam at the level of spinal cord may be responsible for inhibition the conduction of afferent impulses from the muscle spindle and cutaneous receptors for cold to the higher centers and thereby subsiding of shivering.

Thermoregulatory inhibition by midazolam appears to depend minimally on the administered dose. For example, reduction in the vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds with high plasma concentrations[10] was similar to the reduction in core temperature after relatively small premedication doses of the drug.[27] Thus, even small doses given as premedication produce significant reductions in body temperature as seen in the current and previous studies.[27]

The agents used for the treatment or prophylaxis of shivering during regional anesthesia should not cause nausea and vomiting or hemodynamic instability. Midazolam has antiemetic effect.[28] Possible mechanisms for this effect of midazolam may be GABA receptor antagonism, inhibition of dopamine release and anxiolytic effects.[29,30]

Ondansetron is specific inhibitor of the 5-HT3 system. Perhaps 5-HT3 inhibition has an antishivering effect but given the variety of neurotransmitter systems known to be also involved in regulating shivering, an inhibitory effect at the 5-HT3 receptor probably results from a generalized thermoregulatory inhibition at the level of the hypothalamus where the bulk of thermoregulatory control occurs. Thus, the PAS effect of ondansetron is independent of intraoperative core hypothermia suggesting that it inhibits thermoregulatory responses by a central mechanism.[30,31]

Ondansetron is notable for its lack of hemodynamic side effects.[32,33] We had demonstrated that ondansetron 8 mg given after SA compare with control group reduced the incidence of PAS in adults during the administration of SA. This implies that 5-HT3 pathways are also involved in the multifactorial control of PAS.

A limitation of our study may be that we did not investigate the efficacy of ketamine-midazolam combination or ondansetron in preventing shivering after epidural anesthesia.

CONCLUSION

Prophylactic use of ondansetron 8 mg IV was comparable to ketamine 0.25 mg/kg/iv + midazolam 37.5 μg/kg IV in preventing shivering developed during SA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Anesthesiology and Critical Care Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to sincerely thank the support of all the colleagues in Kashani Hospital Medical Center affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Isfahan, Iran. And also, our special thanks go to the patients, who wholeheartedly and actively assisted us to carry out this research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ozaki M, Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R, Schroeder M, Moayeri A, et al. Thermoregulatory thresholds during epidural and spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:282–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeon YT, Jeon YS, Kim YC, Bahk JH, Do SH, Lim YJ. Intrathecal clonidine does not reduce post-spinal shivering. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:1509–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciofolo MJ, Clergue F, Devilliers C, Ben Ammar M, Viars P. Changes in ventilation, oxygen uptake, and carbon dioxide output during recovery from isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:737–41. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guffin A, Girard D, Kaplan JA. Shivering following cardiac surgery: Hemodynamic changes and reversal. J Cardiothorac Anesth. 1987;1:24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0888-6296(87)92593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buggy D, Higgins P, Moran C, O’Donovan F, McCarroll M. Clonidine at induction reduces shivering after general anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:263–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03015363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glosten B, Hynson J, Sessler DI, McGuire J. Preanesthetic skin-surface warming reduces redistribution hypothermia caused by epidural block. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:488–93. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda T, Kazama T, Sessler DI, Toriyama S, Niwa K, Shimada C, et al. Induction of anesthesia with ketamine reduces the magnitude of redistribution hypothermia. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:934–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagir O, Gulhas N, Toprak H, Yucel A, Begec Z, Ersoy O. Control of shivering during regional anaesthesia: Prophylactic ketamine and granisetron. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:44–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkin DA. Postoperative spasticity and shivering. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:725–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1984.tb06502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurz A, Sessler DI, Annadata R, Dechert M, Christensen R, Bjorksten AR. Midazolam minimally impairs thermoregulatory control. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:393–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199508000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honarmand A, Safavi MR. Comparison of prophylactic use of midazolam, ketamine, and ketamine plus midazolam for prevention of shivering during regional anaesthesia: A randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:557–62. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner C, Perren M. Inhibition of anaesthetic-induced emesis by a NK1 or 5-HT3 receptor antagonist in the house musk shrew, Suncus murinus. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1643–4. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson NJ, Malcolm JL. Initiation and inhibition of shivering in the rat: Interaction between peripheral and central factors. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1982;9:89–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1982.tb00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hindle AT. Recent developments in the physiology and pharmacology of 5-hydroxytryptamine. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:395–407. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelsaka E, Baris S, Karakaya D, Sarihasan B. Comparison of ondansetron and meperidine for prevention of shivering in patients undergoing spinal anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai YC, Chu KS. A comparison of tramadol, amitriptyline, and meperidine for postepidural anesthetic shivering in parturients. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:1288–92. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200111000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson E, David A, MacKenzie N, Grant IS. Sedation during spinal anaesthesia: Comparison of propofol and midazolam. Br J Anaesth. 1990;64:48–52. doi: 10.1093/bja/64.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buggy DJ, Crossley AW. Thermoregulation, mild perioperative hypothermia and postanaesthetic shivering. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:615–28. doi: 10.1093/bja/84.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendolin H, Länsimies E. Skin and central temperatures during continuous epidural analgesia and general anaesthesia in patients subjected to open prostatectomy. Ann Clin Res. 1982;14:181–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank SM, Beattie C, Christopherson R, Norris EJ, Rock P, Parker S, et al. Epidural versus general anesthesia, ambient operating room temperature, and patient age as predictors of inadvertent hypothermia. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:252–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsukawa T, Sessler DI, Christensen R, Ozaki M, Schroeder M. Heat flow and distribution during epidural anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:961–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199511000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dal D, Kose A, Honca M, Akinci SB, Basgul E, Aypar U. Efficacy of prophylactic ketamine in preventing postoperative shivering. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:189–92. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma DR, Thakur JR. Ketamine and shivering. Anaesthesia. 1990;45:252–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinoshita T, Suzuki M, Shimada Y, Ogawa R. Effect of low-dose ketamine on redistribution hypothermia during spinal anesthesia sedated by propofol. J Nippon Med Sch. 2004;71:92–8. doi: 10.1272/jnms.71.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hales JR. Skin arteriovenous anastomoses, their control and role in thermoregulation. In: Johansen K, Burggren W, editors. Cardiovascular Shunts: Phylogenetic, Ontogenetic and Clinical Aspects. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard; 1985. pp. 433–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adam RD, Victor M, Ropper AH. Motor paralysis. In: Adam RD, Victor M, Ropper AH, editors. Principles of Neurology. 6th ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill Inc; 1997. pp. 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsukawa T, Hanagata K, Ozaki M, Iwashita H, Koshimizu M, Kumazawa T. I.m. midazolam as premedication produces a concentration-dependent decrease in core temperature in male volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:396–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarhan O, Canbay O, Celebi N, Uzun S, Sahin A, Coskun F, et al. Subhypnotic doses of midazolam prevent nausea and vomiting during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. Minerva Anestesiol. 2007;73:629–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer KP, Dom PM, Ramirez AM, O’Flaherty JE. Preoperative intravenous midazolam: Benefits beyond anxiolysis. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sessler DI. Temperature monitoring. In: Miller RD, editor. Anesthesia. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. pp. 1363–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guyton AC. Body temperature, temperature regulation and fever. In: Guyton AC, editor. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991. pp. 886–98. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diemunsch P, Conseiller C, Clyti N, Mamet JP. Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide in the treatment of established postoperative nausea and vomiting. The French Ondansetron Study Group. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:322–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.3.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safavi MR, Honarmand A. Low dose intravenous midazolam for prevention of PONV, in lower abdominal surgery – Preoperative vs intraoperative administration. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2009;20:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]