Abstract

Oceanobacillus picturae is a strain of a moderately halophilic bacterium, first isolated from a mural painting. We demonstrate, for the first time, the culture of human Oceanobacillus picturae, strain S1T, whose genome is described here, from a stool sample collected from a 25-year-old Saoudian healthy individual. We used a slightly modified standard culture medium adding 100 g/L of NaCl. We provide a short description of this strain including its MALDI-TOF spectrum, the main identification tool currently used in clinical microbiology. The 3,675,175 bp long genome exhibits a G + C content of 39.15 % and contains 3666 protein-coding and 157 RNA genes. The draft genome sequence of Oceanobacillus picturae has a similar size to the Oceanobacillus kimchii (respectively 3.67 Mb versus 3.83 Mb). The G + C content was higher compared with Oceanobacillus kimchii (respectively 39.15 % and 35.2 %). Oceanobacillus picturae shared almost identical number of genes (3823 genes versus 3879 genes), with a similar ratio of genes per Mb (1041 genes/Mb versus 1012 genes/Mb).

The genome sequencing of Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1 isolated for the first time in a human, will be added to the 778 genome projects from the gastrointestinal tract listed by the international consortium Human Microbiome Project.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40793-015-0081-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Oceanobacillus picturae, Genome, Halophilic bacteria, Human gut, Culturomics

Introduction

A pure culture remains essential in microbiology. Nevertheless, metagenomics studies replaced culture methods entirely with regards to the exploration of complex ecosystems. The Human Microbiome Project (HMP) is an initiative with the goal of identifying and characterizing the microorganisms which are found in association with both healthy and diseased humans. To date (25 March 2015), 778 genome projects from the gastrointestinal tract are listed by HMP [1]. Since 2012, we applied microbial culturomics (based on the multiplication of the culture condition with a rapid identification method by MALDI-TOF) in order to extend the human gut composition. Testing more than 500,000 colonies by MALDI-TOF, we isolated more than 700 different bacterial species including more than 90 new bacterial species and 180 previously known bacterial species but first isolated in humans [1]. Each new bacterial species was described by taxonogenomics, a polyphasic approach adding genome sequencing and MALDI-TOF comparison in addition to classic phenotypic characteristics [2]. In addition, in order to make the genome sequencing data available to the international scientific community, we propose the sequencing of the genomes of all bacterial species we isolated in humans, for which no genome sequencing was previously available [1]. This will facilitate the future analysis of metagenomics studies. These strains are available for the scientific community (Collection de Souches de l’Unité des Rickettsies = CSUR). Herein, we report the genome sequencing of Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1 isolated for the first time in humans.

The genus Oceanobacillus was first described by Lu et al. in 2001 [3] and was emended by Yumoto et al. in 2005 [4]. These bacteria belong to the phylum Firmicutes, within the family Bacillaceae. This genus included 17 recognized species and two subspecies. These bacteria are motile Gram-positive rods, growing obligatory aerobically or facultative anaerobically. Some of them are moderately halophilic bacteria. Bacteria from the genus Oceanobacillus were isolated from diverse environmental samples [5–14], including deep-sea sediment cores [3], salt fields [11], fermented shrimp paste samples [12], soy sauce production equipment [13], and traditional Korean fermented food [14]. Oceanobacillus picturae was originally described as Virgibacillus picturae in 2003 and was isolated from a mural painting from the Servilia tomb of the Roman necropolis at Carmona (Seville, Spain) [5]. Lee et al. reclassified this species as Oceanobacillus picturae in 2006 [6]. In addition to these validly published species, as a part of a large culturomics study [15], we isolated another Oceanobacillus species (“Oceanobacillus massiliensis”) from human fecal flora [16].

In this study we isolated for the O. picturae from humans for the first time. Strain S1 was isolated from a stool sample of a 25 year-old obese Saudi individual (BMI = 51 kg/m2) using a modified Columbia agar (Becton Dickinson, Pont de Claix, France) adding 100 g/L of NaCl. We described here the genome sequencing of this bacterium.

Organism information

Classification and features

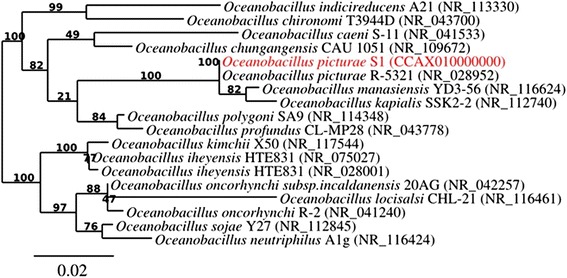

A stool specimen was collected from a 25-year-old Saudi obese patient. The patient gave informed and signed consent. The study and the assent procedure were approved by the Ethics Committees of the King Abdulaziz University, King Fahd medical Research Center, Saudi Arabia, under agreement number 014-CEGMR-2-ETH-P, and of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche 48, Faculty of Medicine, Marseille, France, under agreement number 09–022. The stool sample was preserved at −80 °C after collection and sent to Marseille. O. picturae strain S1T (Table 1) was isolated in December 2013 by aerobic cultivation on a culture medium consisting of a Columbia broth culture medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France) modified by the addtion of 100 g/L of NaCl with a pH adjusted to 7.5. O. picturae strain S1 had a 16S rRNA sequence similarity of 99.8 % with the reference strain O. picturae strain LMG19492T (Genbank accession number NR_028952) (Fig. 1). This strain was deposited in the CSUR (under number P887).

Table 1.

Classification and general features of Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1T according to the MIGS recommendations [17]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain: Bacteria | TAS [18] | |

| Phylum: Firmicutes | TAS [19–21] | ||

| Class: Bacilli | TAS [22, 23] | ||

| Order: Bacillales | TAS [24, 25] | ||

| Family: Bacillaceae | TAS [26] | ||

| Genus: Oceanobacillus | TAS [3] | ||

| Species: Oceanobacillus picturae | IDA [5, 6] | ||

| Type strain: S1T | IDA | ||

| Gram stain | Positive | IDA | |

| Cell shape | Rod shaped | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile by polar flagellum | IDA | |

| Sporulation | Non sporulating | IDA | |

| Temperature range | Mesophile | IDA | |

| Optimum temperature | 37 °C | IDA | |

| pH range; Optimum | 6.5–7.5; 7 | ||

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | 0.5 to 20 % | IDA |

| Optimum salinity | 10 % | IDA | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic | IDA |

| Carbon source | Unknown | IDA | |

| Energy source | Unknown | IDA | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Human gut | IDA |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free living | IDA |

| Pathogenicity | Unknown | NAS | |

| Biosafety level | 2 | IDA | |

| MIGS-14 | Isolation | Human feces | IDA |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Jeddah, Saudi Arabia | IDA |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | December 2013 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 21.422487 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.1 | Longitude | 39.856184 | IDA |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | surface | IDA |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | 0 m above sea level | IDA |

aEvidence codes - IDA Inferred from Direct Assay, TAS Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature), NAS Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [27]. If the evidence is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a live isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1T relative to other strains of the genus Oceanobacillus. Strain S1T (CSUR P1091 = DSM 28586) relative to other type strains within the genus Oceanobacillus. The strains and their corresponding GenBank accession numbers for 16S rRNA genes are (type = T): Oceanobacillus indicireducens strain A21T, NR_113330, Oceanobacillus chironomi strain T3944DT, NR_043700, Oceanobacillus caeni strain S-11 T, NR_041533, Oceanobacillus chungangensis strain CAU 1051T, NR_109672, Oceanobacillus picturae strain R-5321T, NR_028952, Oceanobacillus manasiensis strain YD3-56T, NR_116624, Oceanobacillus kapialis strain SSK2-2T, NR-112740, Oceanobacillus polygoni strain SA9T, NR_114348, Oceanobacillus profundus strain CL-MP28T, NR_043778, Oceanobacillus kimchii strain X50T, NR_117544, Oceanobacillus iheyensis strain HTE831T, NR_075027, Oceanobacillus iheyensis strain HTE831T, NR_028001, Oceanobacillus oncorhynchi subsp.incalanensis strain 20AGT, NR_042257, Oceanobacillus locisalsi strain CHL-21T, NR_116461, Oceanobacillus sojae strain Y27T, NR_112845 and Oceanobacillus neutriphilus strain A1gT, NR_116424. Phylogeny pipeline [28] was used, wherein sequences were aligned using MUSCLE [29] alignment curation by Gblocks [30] and construction of phylogenic tree performed using PhyML [31]. Numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values obtained by repeating the analysis 100 times. The scale bar represents a 2 % nucleotides sequences divergence

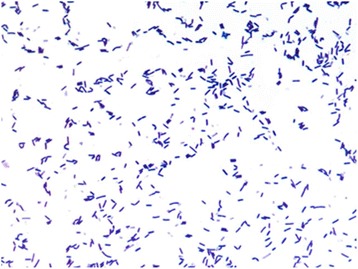

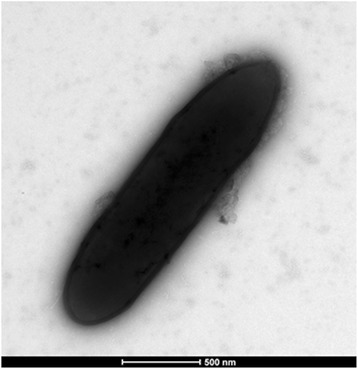

Strain S1 colonies were observed on sheep blood agar (Biomérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) after 24 h of aerobic incubation at 37 °C. The colonies were greyish, 3–4 mm in diameter. Gram staining revealed Gram-positive bacilli (Fig. 2) and electron microscopy performed using a Morgani 268D (Phillips) showed rods with a mean length of 1.5 μm and a mean width of 0.5 μm (Fig. 3). Optimal growth was observed at 37 °C and strain S1 grew only under aerobe conditions.

Fig. 2.

Gram staining of Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1T

Fig. 3.

Transmission electron microscopy of Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1T, using a Morgani 268D (Philips) at an operating voltage of 60 kV. The scale bar represents 500 nm

Extended feature descriptions

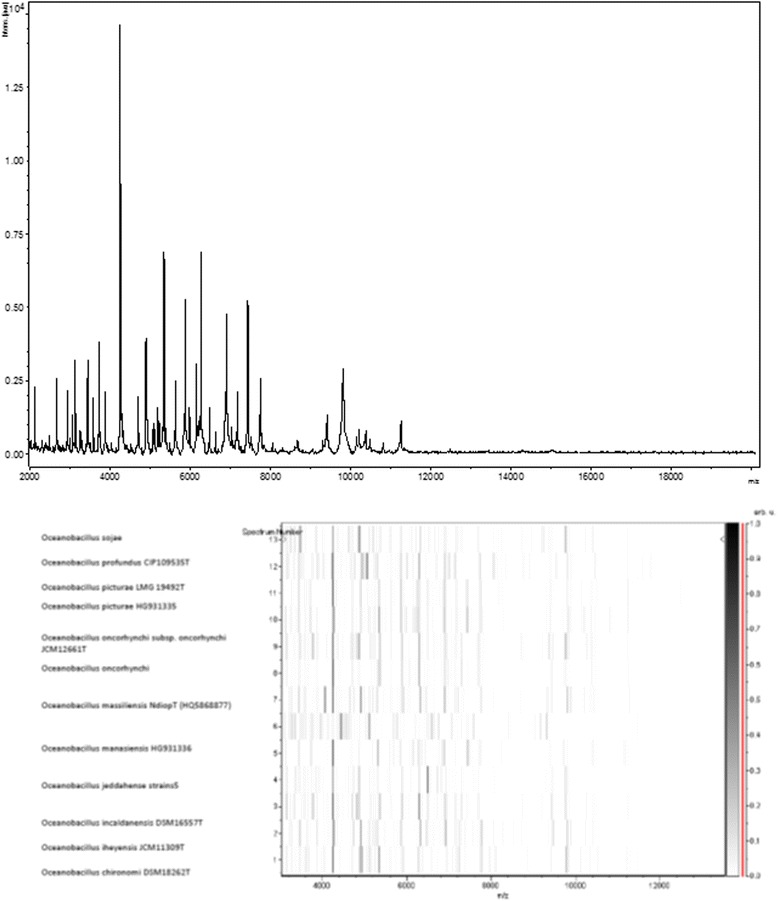

We added in the description the MALDI-TOF spectra of this bacterium. Indeed, mass spectrometry has become the reference identification method in clinical microbiology [1]. Matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS protein analysis was carried out. Briefly, a pipette tip was used to pick one isolated bacterial colony from a culture agar plate and to spread it as a thin film on a MALDI-TOF target plate (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). Twelve distinct deposits were done for the strain S1 from twelve isolated colonies. After air-drying, 2 μl matrix solution (saturated solution of α-cyanohydroxycinnaminic acid in 50 % aqueous acetonitrile containing 2.5 % trifluoroacetic acid) per spot was applied. MALDI-TOF MS was conducted using the Microflex LT spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics). All spectra were recorded in the positive linear mode for the mass range of 2000 to 20,000 Da (parameter settings: ion source 1 (ISI), 20 kV; IS2, 18.5 kV; lens, 7 kV). A spectrum was obtained after 675 shots with variable laser power. The time of acquisition was between 30 s and 1 min per spot. The twelve spectra of strain S1 were imported into the MALDI BioTyper software (version 2.0, Bruker) and analyzed by standard pattern matching (with default parameter settings) against the main spectra of over 4108 bacteria including the spectra from the most closely related species including Oceanobacillus oncorhynchiCIP108867T, Oceanobacillus profundusCIP 109535T, Oceanobacillus chironomiCIP 109536T, Oceanobacillus iheyensisCIP 107618T, and Oceanobacillus oncorhynchi subsp. incaldanensisCIP 109235T, and Oceanobacillus sojae. In addition to these validly published species, we compared the O. picturae spectrum with spectra of Oceanobacillus massiliensis strain N’Diop and ‘Oceanobacillusmanasiensis’ (HG931336). The resulting score was > 2, matching with Oceanobacillus picturaeCIP 108264 T. The identification method included the m/z from 3000 to 15,000 Da. For every spectrum, a maximum of 100 peaks were compared with spectra in the database. We added the spectrum from strain S1T to our database (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Reference mass spectrum from Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1T. Spectra from 10 individual colonies were compared and a reference spectrum was generated

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

The O. picturae genome was sequenced as part of a culturomics study aiming to isolate all bacterial species colonizing the human gut [1] (Table 2). To the best of our knowledge, O. picturae represent the fifth genome sequenced into the Oceanobacillus genus and the first genome of O. picturae. The genome accession number is CCAX00000000 and consists of 5 contigs without gaps. Table 3 shows the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance.

Table 2.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | 1 mate-paired, 5-kb library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | MiSeq Illumina |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 85× |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Spades |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| Locus Tag | EMBL | |

| Genbank ID | CCAX00000000 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | May, 2014 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0100993 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJEB5522 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | CSUR P887 |

| Project relevance | Human gut microbiota |

Table 3.

Summary of genome: 5 scaffolds

| Label | Size (bp) | Topology | INSDC identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCAFFOLD00001 | 2,198,765 | Unknown | CCAX010000001 |

| SCAFFOLD00002 | 704,800 | Unknown | CCAX010000002 |

| SCAFFOLD00003 | 480,759 | Unknown | CCAX010000003 |

| SCAFFOLD00004 | 282,316 | Unknown | CCAX010000004 |

| SCAFFOLD00005 | 8535 | Unknown | CCAX010000005 |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

O. picturae strain S1T (CSUR P1091 = DSM 28586) was grown at 37 °C in an aerobic atmosphere on ten Petri dishes. The bacteria were harvested and resuspended in 4 × 100 μL of TE buffer. Then, 200 μL of this suspension was diluted in 1 mL TE buffer for lysis treatment that included a 30- min incubation with 2.5 μg/μL lysozyme at 37 °C, followed by an overnight incubation with 20 μg/μL proteinase-K at 37 °C. Extracted DNA was then purified using 3 successive phenol-chloroform extractions and ethanol precipitation at −20 °C overnight. After centrifugation, the DNA was resuspended in 160 μL TE buffer. The yield and concentration were measured by the Quant-it Picogreen kit (Invitrogen) on the Genios-Tecan fluorometer at 88.6 ng/μl.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Genomic DNA of Oceanobacillus picturae was sequenced using MiSeq Technology (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) with the mate pair strategy. The gDNA was barcoded in order to be mixed with 11 other projects with the Nextera Mate Pair sample prep kit (Illumina). The gDNA was quantified by a Qubit assay with the high sensitivity kit (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to 40.5 ng/μl. The mate pair library was prepared with 1 μg of genomic DNA using the Nextera mate pair Illumina guide. The genomic DNA sample was simultaneously fragmented and tagged with a mate pair junction adapter. The profile of the fragmentation was validated on an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a DNA 7500 labchip. The DNA fragments ranged in size from 1 kb up to 10 kb. No size selection was performed and only 14 ng of tagmented fragments were circularized. The circularized DNA was mechanically sheared to small fragments with an optimum at 696 bp on the Covaris device S2 in microtubes (Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA). The library profile was visualized on a High Sensitivity Bioanalyzer LabChip (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The libraries were normalized at 2 nM and pooled. After a denaturation step and dilution at 10pM, the pool of libraries was loaded onto the reagent cartridge and then onto the instrument along with the flow cell. Automated cluster generation and sequencing runs were performed in a single 42-h run in a 2x251-bp. Total information of 4.7 Gb was obtained from a 488 K/mm2 cluster density with a cluster passing quality control filters of 97.2 % (9,590,000 clusters). Within this run, the index representation for O. picturae was determined to be 11.16 %. Illumina reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic [32], then assembled through Spades software [33, 34]. Contigs obtained were combined together by SSpace [35] and Opera software v1.2 [36] helped by GapFiller V1.10 [37] to reduce the set. Some manual refinements using CLC Genomics v7 software cCLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark) and homemade tools improved the genome. Finally, the draft genome of Oceanobacillus picturae consists of 5 contigs without gaps.

Genome annotation

Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using RNAmmer [38], ARAGORN [39], Rfam [40], PFAM [41], Infernal [42]. Coding DNA sequences (CDSs) were predicted using Prodigal [43] and functional annotation was achieved using BLAST+ [44] and HMMER3 [45] against the UniProtKB database [46].

Genome properties

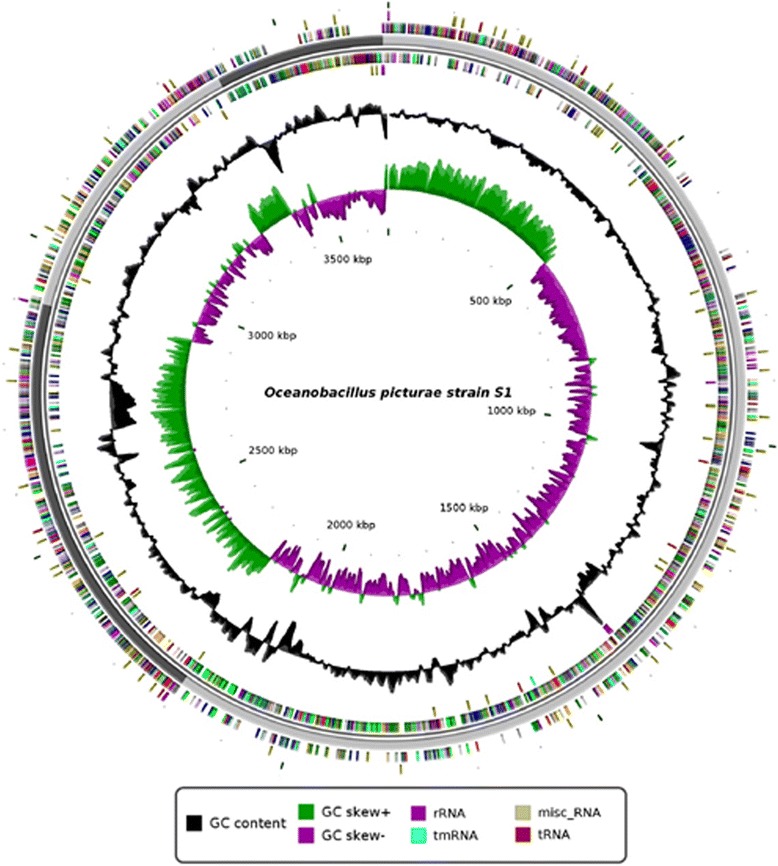

The genome of Oceanobacillus picturae contained 3,675,175 bp with a G + C content of 39.15 % (Fig. 5, Tables 3 and 4). The genome was shown to encode at least 157 predicted RNA including 14 rRNA, 31 tRNA, 1 tmRNA and 111 miscellaneous RNA. In addition, 3666 genes were identified, representing a coding capacity of 3,125,691 bp (coding percentage: 85.05 %). Among these genes, 269 (7.34 %) were found as putative proteins and 891 (24.3 %) were assigned as hypothetical proteins. Moreover, 3595 genes matched at least one sequence in Clusters of Orthologous Groups database [47] with BLASTP default parameters. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Tables 4 and 5. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 6 [48].

Fig. 5.

Circular representation of the Oceanobacillus picturae genome. Circles from the center to the outside: GC screw (green/purple), GC content (black), tRNA (dark red), rRNA (purple), tmRNA (blue), miscellaneous RNA (beige) on forward strand, genes on forward strand colored by COGs categories, scaffolds in alternative grays, genes on reverse strand colored by COGs, tRNA (dark red), rRNA (purple), tmRNA (blue), miscellaneous RNA (beige) on reverse strand

Table 4.

Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome

| Attribute | Value | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 3,675,175 | 100 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 3,125,691 | 85.05 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 1,438,948 | 39.15 |

| DNA scaffolds | 3,675,175 | 100 |

| Total genes | 3823 | 100 |

| Protein coding genes | 3666 | 85.05 |

| RNA genes | 157 | 4.11 |

| Pseudo genes | 269 | 7 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 1751 | 45.8 |

| Genes with function prediction | 2775 | 72.59 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 3595 | 98.06 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 183 | 4.79 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 229 | 5.99 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1074 | 28.09 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0 |

Table 5.

Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories

| Code | Valuea | % of total | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 197 | 5.37 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 4 | 0.12 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 263 | 7.18 | Transcription |

| L | 173 | 4.73 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 4 | 0.12 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 56 | 1.54 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 1 | 0.02 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 71 | 1.93 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 166 | 4.53 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 193 | 5.27 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 81 | 2.2 | Cell motility |

| Z | 4 | 0.12 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 75 | 2.05 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 114 | 3.12 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 181 | 4.95 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 240 | 6.56 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 298 | 8.12 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 91 | 2.48 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 113 | 3.07 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 103 | 2.8 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 214 | 5.84 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 62 | 1.68 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 475 | 12.97 | General function prediction only |

| S | 484 | 13.2 | Function unknown |

aThe total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Genome comparison with O. picturae with O. kimchii

We performed a brief comparison of Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1 genome sequence against Oceanobacillus kimchii X50 (NZ_CM001792), which is currently the closest available sequenced genome based on rRNA 16S identity. The draft genome sequence of Oceanobacillus picturae has a similar size to the Oceanobacillus kimchii (respectively 3.67 Mb versus 3.83 Mb). The G + C content was higher as compared to Oceanobacillus kimchii (respectively 39.15 and 35.2 %). Oceanobacillus picturae shared an almost identical number of genes (3823 genes versus 3879 genes), with a similar ratio of genes per Mb (1041 genes/Mb versus 1012 genes/Mb). Additional file 1: Table S1 presents the difference in gene number (percentage) related to each COG categories between O. pictuare and O. kimchii. The proportion of COGs is very similar between the two species. The maximum difference is related to the COG “Carbohydrate transport and metabolism” which does not exceed 1.15 %. Additional file 2: Table S2 presents the associated MIGS records.

Conclusion

Oceanobacillus picturae strain S1 was the first strain of this bacterial species isolated from the human gut. The G + C % content of the genome was 39.15 %. The 16S rRNA and genome sequences were deposited in EMBL/EBI database under accession numbers HG931335 and CCAX00000000 respectively.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR), King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. (HiCi-1434-140-30). The authors therefore acknowledge with thanks the DSR technical and financial support.

We thank Karolina Griffiths for English reviewing.

Abbreviations

- CSUR

Collection de souches de l’Unité des Rickettsies

- DSM

Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen

Additional files

Percentage of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories for O. picturae and O. kimchii X50. (DOC 45 kb)

Associated MIGS record. (DOC 70 kb)

Footnotes

Jean-Christophe Lagier and Saber Khelaifia contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DR conceived the study, JCL, PEF, DR participated in its design and drafted the manuscript, JCL, SK, EIA, OC, FB, AAJF, MY, HBH contributed materials and analyses and helped to draft the manuscript, CR performed the genome sequencing. OC performed the genome analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Human microbiome project [http://www.hmpdacc.org/catalog/]

- 2.Lagier J-C, Hugon P, Khelaifia S, Fournier PE, La Scola B, Raoult D. The rebirth of culture in microbiology through the example of culturomics to study human gut microbiota. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:237–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramasamy D, Mishra AK, Lagier JC, Padhmanabhan R, Rossi-Tamisier M, Sentausa E, et al. A polyphasic strategy incorporating genomic data for the taxonomic description of new bacterial species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:384–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.057091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu J, Nogi Y, Takami H. Oceanobacillus iheyensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a deep-sea extremely halotolerant and alkaliphilic species isolated from a depth of 1050 m on the Iheya Ridge. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;205:291–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yumoto I, Hirota K, Nodasaka Y, Nakajima K. Oceanobacillus oncorhynchi sp. nov., a halotolerant obligate alkaliphile isolated from the skin of a rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), and emended description of the genus Oceanobacillus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1521–4. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyrman J, Logan NA, Busse HJ, Balcaen A, Lebbe L, Rodriguez-Diaz M, et al. Virgibacillus carmonensis sp. nov., Virgibacillus necropolis sp. nov. and Virgibacillus picturae sp. nov., three novel species isolated from deteriorated mural paintings, transfer of the species of the genus salibacillus to Virgibacillus, as Virgibacillus marismortui comb. nov. and Virgibacillus salexigens comb. nov., and emended description of the genus Virgibacillus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53(Pt 2):501–11. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JS, Lim JM, Lee KC, Lee JC, Park YH, Kim CJ. Virgibacillus koreensis sp. nov., a novel bacterium from a salt field, and transfer of Virgibacillus picturae to the genus Oceanobacillus as Oceanobacillus picturae comb. nov. with emended descriptions. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56(Pt 1):251–7. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raats D, Halpern M. Oceanobacillus chironomi sp. nov., a halotolerant and facultatively alkaliphilic species isolated from a chironomid egg mass. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:255–9. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nam JH, Bae W, Lee DH. Oceanobacillus caeni sp. nov., isolated from a Bacillus-dominated wastewater treatment system in Korea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:1109–13. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirota K, Aino K, Nodasaka Y, Yumoto I. Oceanobacillus indicireducens sp. nov., a facultative alkaliphile that reduces an indigo dye. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:1437–42. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.034579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YG, Choi DH, Hyun S, Cho BC. Oceanobacillus profundus sp. nov., isolated from a deep-sea sediment core. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:409–13. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romano I, Lama L, Nicolaus B, Poli A, Gambacorta A, Giordano A. Oceanobacillus oncorhynchi subsp. incaldanensis subsp. nov, an alkalitolerant halophile isolated from an algal mat collected from a sulfurous spring in Campania (Italy), and emended description of Oceanobacillus oncorhynchi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:805–10. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namwong S, Tanasupat S, Lee KC, Lee JS. Oceanobacillus kapialis sp. nov., from fermented shrimp paste in Thailand. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:2254–9. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.007161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tominaga T, An SY, Oyaizu H, Yokota A. Oceanobacillus sojae sp. nov. isolated from soy sauce production equipment in Japan. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;55:225–32. doi: 10.2323/jgam.55.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whon TW, Jung MJ, Roh SW, Nam YD, Park EJ, Shin KS, et al. Oceanobacillus kimchii sp. nov. isolated from a traditional Korean fermented food. J Microbiol. 2010;48:862–6. doi: 10.1007/s12275-010-0214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagier JC, Armougom F, Million M, Hugon P, Pagnier I, Robert C, et al. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(12):1185–93. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roux V, Million M, Robert C, Magne A, Raoult D. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Oceanobacillus massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2013;9:370–84. doi: 10.4056/sigs.4267953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray RGE. The Higher Taxa, or, a Place for Everything? In: Holt JG, editor. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 1. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. 2. New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 119–69. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbons NE, Murray RGE. Proposals Concerning the Higher Taxa of Bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1978;28:1–6. doi: 10.1099/00207713-28-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig W, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB. Class I. Bacilli class nov. In: De Vos P, Garrity G, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer KH, Whitman WB, editors. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 3. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Euzéby J. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. List no. 132. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:469–72. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.022855-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer A. Untersuchungen über bakterien. Jahrbücher für Wissenschaftliche Botanik. 1895;27:1–163. [Google Scholar]

- 27.List Editor Validation List no. 85. Validation of publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSEM. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:685–90. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-3-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, et al. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W465–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:540–52. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59(3):307–21. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lohse M, Bolger AM, Nagel A, Fernie AR, Lunn JE, Stitt M, et al. RobiNA: a user-friendly, integrated software solution for RNA-Seq-based transcriptomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W622–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurk S, Bankevich A, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Korobeynikov A, Lapidus A, et al. Assembling single-cell genomes and mini-metagenomes from chimeric MDA products. J Comput Biol. 2013;20(10):714–37. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2013.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–77. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(4):578–9. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Gao S, Sung WK, Nagarajan N. Opera: reconstructing optimal genomic scaffolds with high-throughput paired-end sequences. J Comput Biol. 2011;18(11):1681–91. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2011.0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boetzer M, Pirovano W. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laslett D, Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:11–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:439–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(10):1335–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eddy SR. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comp Biol. 2011;7(10):e1002195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.The UniProt Consortium Ongoing and future developments at the UniversalProtein Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D214–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genomoe-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]