Abstract

Introduction:

Concerns about retention are a major barrier to conducting studies enrolling homeless individuals. Since smoking is a major problem in homeless communities and research on effective methods of promoting smoking cessation is needed, we describe strategies used to increase retention and participant characteristics associated with retention in smoking cessation study enrolling homeless adults.

Methods:

The parent study was a 2-group randomized controlled trial with 26-week follow-up enrolling 430 homeless smokers from emergency shelters and transitional housing units in Minneapolis/Saint Paul, MN, USA. Multiple strategies were used to increase retention, including conducting visits at convenient locations for participants, collecting several forms of contact information from participants, using a schedule that was flexible and included frequent low-intensity visits, and providing incentives. Participant demographics as well as characteristics related to tobacco and drug use and health status were analyzed for associations with retention using univariate and multivariate analysis.

Results:

Overall retention was 75% at 26 weeks. Factors associated with increased retention included greater age; having healthcare coverage; history of multiple homeless episodes, lower stress level; and higher PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) score. A history of excessive drinking and drug use were associated with decreased retention.

Conclusions:

It is possible to successfully retain homeless individuals in a smoking cessation study if the study is designed with participants’ needs in mind.

Introduction

One of the major barriers to conducting studies with members of homeless communities is concern about recruitment and retention. Many characteristics common in homeless populations have been associated with increased risk for study attrition. Among these are male gender, non-White race, lower educational attainment, poor physical and mental health, high stress, financial difficulties, and irregular use of health care services.1–3 In addition, individuals who lack a fixed residence may be difficult to track using conventional methods.4 In a study by Ball and colleagues enrolling homeless persons diagnosed with both substance dependence and a personality disorder, only 12 out of 52 participants completed at least one monthly assessment as well as either the end-of-treatment or 3-month follow-up assessment.5 The authors of this study cited extreme difficulty in tracking members of a highly mobile population. It is, however, possible to overcome such difficulties, as evidenced by other studies that have had considerable success with retaining homeless participants in longitudinal trials. In a study of interventions to prevent recurrent homelessness among men with severe mental illness, Susser and colleagues6 obtained follow-up information at 18 months from 94 out of 96 participants. They incorporated a number of elements in their study design specifically to address the challenges posed by working with homeless adults. For example, they tried to make the whole atmosphere of the study as welcoming as possible; participants worked with the same staff member for the entire study; the study office was set up to be comfortable and accessible; interviews were set up as conversations; and participants were provided with travel money and other incentives that showed that staff valued participants’ time. The staff also gathered extensive information about participants’ social networks and daily activities, so they could locate participants who did not make it to appointments.4 Other studies conducted in homeless populations have achieved follow-up rates between 67% and 88%.7–13 These studies provide evidence that high retention can be achieved when working with the homeless if care is taken to design a study that meets participants’ needs.

However, it is still unclear whether it is possible to successfully retain homeless individuals in a smoking cessation trial. High levels of substance abuse, psychiatric illness, and competing needs make it challenging to promote smoking cessation among the homeless. Still there is no doubt smoking is a serious health issue in homeless populations: multiple studies have shown smoking rates in excess of 70% among the homeless,14–19 leading to high rates of smoking-related illness.17–22 There is also evidence that many homeless smokers are interested in quitting.15,23–25 Health care providers are increasingly aware of this problem,26 but lack evidence regarding effective ways to promote smoking cessation among homeless patients.27 Power to Quit is the first large-scale, randomized clinical trial that has investigated smoking cessation interventions in a homeless population.12,28

In this paper, we describe strategies that were used to promote retention in the Power to Quit study and participant factors associated with improved retention. If homeless participants susceptible to dropping out of a smoking cessation program can be identified at the beginning of a study, additional measures could be implemented to enhance retention.2,3,29

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Details of the Power to Quit study design and recruitment are described in separate manuscripts.30,31 Briefly, 430 homeless adults who were current cigarette smokers were recruited from 8 emergency shelters and transitional housing units in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul metro area between May 2009 and August 2010. Participants were classified as homeless based on the 1987 Stewart B. McKinney Act, in which homelessness was defined as anyone lacking a “fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence” or “one whose primary nighttime residence is a supervised publicly or privately operated shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations, transitional housing, or other supportive housing program or a public or private place not meant for human habitation”.32 All participants were provided with 8 weeks of treatment with the 21-mg nicotine patch. Participants were randomly assigned to either a standard care (SC) or motivational interviewing (MI) counseling condition. The SC group received one-time brief advice to quit at study outset. The MI group received six MI sessions at weeks 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 following randomization that targeted smoking cessation and adherence to nicotine patch therapy. Assessments were conducted at weeks 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 26. Retention visits were conducted by outreach workers at weeks 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, and 24 to update participants’ contact information and address any difficulties participants might be having with the study. The primary outcome was 7-day point prevalence abstinence at week 26, verified by exhaled carbon monoxide. Salivary cotinine testing was performed if a participant reported abstinence but exhaled carbon monoxide was greater than 10 ppm.

Eligibility criteria are also described elsewhere.33 Briefly, they included current homelessness, current smoking of at least 1 cigarette per day, lifetime smoking of at least 100 cigarettes, and age 18 or older. We excluded participants who were actively psychotic, suffered from concurrent medical conditions requiring immediate medical care, were unwilling to use nicotine patches, or who had lived in the area for less than 2 months. Participants with stable psychiatric illness were permitted in the study.

Measurements

All surveys were read to or along with participants by trained research assistants including master’s level public health students, medical students, and community outreach staff. At the baseline visit, participants were asked about demographic, psychosocial, and tobacco-related information including homelessness history, smoking behavior and quitting history, mental and physical health, and past and current alcohol and drug use. Participants were asked to rate the importance of quitting and their confidence they could do so on a 1–10 scale. Assessments of psychiatric health included the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression34 and the 4-item perceived stress scale.35 Substance use was assessed using Rost-Burnam screeners, including instruments assessing for history of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence as well questions screening for recent use of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and heroin, or any other recreational drugs (e.g., other stimulants, opioids, sedatives, hallucinogens).36 The M.I.N.I. questionnaire for psychotic disorders37 and the Short Blessed Test38 were used to screen participants for psychosis or cognitive impairment. A feedback survey was given at the end of the week 26 visit and included questions about reasons for completing the program as well as reasons for missing appointments.

Retention Strategies

The Power to Quit study was designed to address the needs of a homeless population with many competing priorities. To make participation convenient for potential participants, recruitment and study visits took place at homeless shelters and transitional housing units. Participants were also provided the option of scheduling their retention visits at other sites in the community, but most preferred to conduct these visits at the shelter where they enrolled. The research team maintained consistent schedules at each site to make it easy for participants to find them. The employees at the facilities where visits were conducted assisted study staff by dedicating office space for staff to conduct visits and counseling sessions and directing participants to these spaces, passing on messages to participants who did not have cell phones, and generally promoting study participation. Each shelter was compensated according to the amount of time they assisted with the study, with payments ranging from $3,500 to $16,425 annually.

The study incorporated community input in other ways besides collaborating with homeless shelters. The research team included community outreach staff (“mobilizers”), individuals who had recently either been homeless themselves or had homeless family members. Community mobilizers assisted with recruitment, administered surveys, and conducted retention visits. A Community Advisory Board (CAB) consisting of program directors and managers from shelters and social service agencies was also created and met up to two times each year during the 4 years of the project. The CAB reviewed the study design, assisted with developing the project name and logo, provided input about potential barriers to study participation, and strategized methods for enhancing recruitment and retention.

An important accommodation was a flexible visit schedule which allowed each visit to be completed within a 2-week window. Participants were also required to complete their baseline visit at least 1 week after and no more than 2 weeks after screening. Participants who did not enroll within 2 weeks of screening were required to rescreen to ensure that data were current. Participants were allowed to rescreen up to two more times; however, participants who missed the window for the baseline visit on three occasions were excluded from participating. The purpose of this was to prevent enrollment of participants unable or unwilling to return for visits at regular intervals.

To enhance retention, participants were asked to provide multiple contact methods (i.e., cell phone number, e-mail address, phone numbers and addresses of friends and relatives, and shelters and other places where participants often spent time). Participants provided consent for staff to leave messages at the latter locations in the event that staff members were not able to contact the participants directly. A staff member routinely contacted each participant 2 days before a scheduled visit. If a participant missed a visit, a staff member would call the participant’s cell phone or the shelter identified as the participant’s most recent nighttime residence every day until the window for the visit closed. If no contact had been made at this point, staff would then make weekly attempts to contact the participant for the remainder of the study and also try other methods of communicating, most often leaving notes on shelter message boards or at the front desk or calling the individuals whom participants had given as contacts. As previously mentioned, community mobilizers conducted biweekly retention visits during weeks 10–24 to stay in touch with participants and to update contact information.

Finally, incentives were offered to assist in retention efforts. At enrollment, participants received a tote bag with the Power to Quit logo and a calendar/planner in which they could record their visit times. Participants received a $20 Visa gift card at each treatment visit. At each of the retention visits, they received a $10 Target gift card plus another small item (e.g., personal care items, water bottle, t-shirt). At the final visit, participants received a $40 Visa gift card and a sweatshirt. Participants also received two bus tokens at each visit to assist with transportation. Total monetary compensation for participants attending all 15 visits was $275 over 6 months.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline variables using frequency and percentage for categorical variables and mean and SD for continuous variables. Variables regarding demographic information, smoking behaviors, physical and mental health status, and alcohol and drug use were analyzed for association with retention at weeks 8 (end of treatment) and 26 (end of study) using Chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and two sample t-tests or Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables. Multiple logistic regression (MLR) with backward selection method was used to examine the association between retention and baseline variables. Separate MLR models were completed for week 8 and 26 and included variables that were associated with retention in univariate analysis with a significance level of p value <.10. Associations with a p value of <.05 were considered significant in the univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

Participants were mostly male (74.7%) and African American (56.3%) with mean age of 44.4 years. Most (63.5%) had a monthly income of less than $400. Approximately 50% had been homeless for more than a year. More complete demographic information can be found in previous publications.33

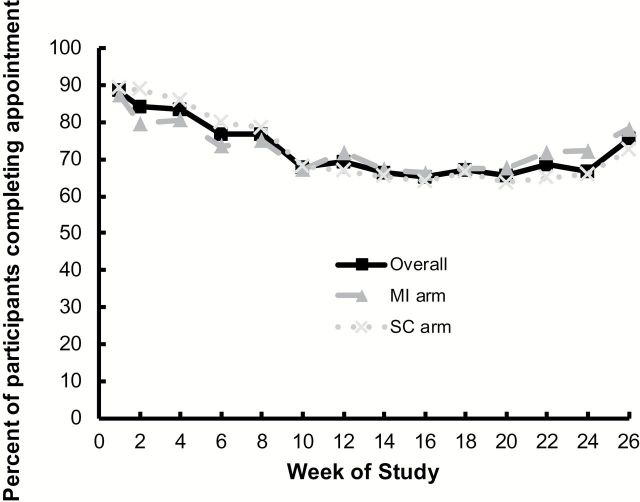

Of the 430 participants randomized, 327 (76%) completed the week 8 visit and 324 (75%) completed the week 26 visit. Of the 106 participants who did not complete the final visit, 101 could not be located. The other five elected to discontinue participation due to illness (n = 1), entering substance abuse treatment (n = 1), or unknown reasons (n = 3). Retention rates were not significantly different between the study arms and were combined for further analysis. Visit completion rates are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Visit completion rate for each visit for all participants and for motivational interviewing (MI) and standard care (SC) arms.

Results of the univariate analysis are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Participant age was the only predictor of retention that was significant at both weeks 8 and 26. Having health care coverage and a lower perceived stress score were associated with increased retention at week 8 only. Several variables related to alcohol abuse were associated with decreased retention at week 8, including considering oneself an excessive drinker and ever drinking as much as a 5th of liquor in 1 day. At week 26, use of recreational drugs other than marijuana, cocaine, or heroin (e.g., sedatives, other opioids, or stimulants); a greater number of homeless episodes in the past 3 years; and a higher level of baseline depression (determined by PHQ-9 score) were associated with increased retention. Those whose current episode of homelessness had lasted less than 6 months or more than a year were also more likely to complete the study than those who had been homeless 6–12 months.

Table 1.

Univariate Associations Between Demographic, Smoking, and Health-Related Variables and Retention at Week 8

| Characteristic | Total (n = 430) | Completed Week 8 (n = 327) | Did not complete Week 8 (n = 103) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 44.35 (9.96) | 45.10 (9.72) | 41.98 (10.40) | .006 |

| Male | 321 (74.7%) | 245 (74.9%) | 76 (73.8%) | .817 |

| Race | ||||

| African American/Black | 242 (56.3%) | 188 (57.5%) | 54 (52.4%) | .446 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 153 (35.6% | 111 (33.9%) | 42 (40.8%) | |

| Other race | 35 (8.1%) | 28 (8.6%) | 7 (6.8%) | |

| Monthly income | ||||

| <$400 | 293 (68.1%) | 225 (68.8%) | 68 (66.0%) | .865 |

| $400–799 | 87 (20.2%) | 65 (19.9%) | 22 (21.4%) | |

| ≥$800 | 50 (11.6%) | 37 (11.3%) | 13 (12.6%) | |

| Homelessness duration | ||||

| <6 months | 143 (33.3%) | 106 (32.5%) | 37 (35.9%) | .103 |

| 6–12 months | 72 (16.8%) | 49 (15.0%) | 23 (22.3%) | |

| ≥1 year | 214 (49.9%) | 171 (52.5%) | 43 (41.7%) | |

| Homeless episodes in past 3 years | ||||

| 1 | 185 (43.2%) | 139 (42.6%) | 46 (45.1%) | .753 |

| 2 or 3 | 152 (35.5%) | 115 (35.3%) | 37 (36.3%) | |

| ≥4 | 91 (21.3%) | 72 (22.1%) | 19 (18.6%) | |

| Smoking characteristics | ||||

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 19.25 (13.73) | 18.79 (14.54) | 20.71 (10.70) | .151 |

| Time to 1st cigarette | ||||

| ≤30 min | 374 (87.0%) | 286 (87.5%) | 88 (85.4%) | .594 |

| >30 min | 56 (13.0%) | 41 (12.5%) | 15 (14.6%) | |

| Time of last quit attempt >24 hr | ||||

| Never quit before | 81 (19.7 %) | 62 (19.9%) | 19 (18.8%) | .840 |

| ≤12 months ago | 153 (37.1%) | 113 (36.3%) | 40 (39.6%) | |

| >12 months ago | 178 (43.2%) | 136 (43.7%) | 42 (41.6%) | |

| Importance of quitting (1–10 scale) | 9.07 (1.63) | 9.14 (1.53) | 8.83 (1.89) | .133 |

| Confidence to quit (1–10 scale) | 7.27 (2.43) | 7.37 (2.40) | 6.93 (2.51) | .111 |

| Physical and mental health | ||||

| Have healthcare coverage | ||||

| No | 77 (17.9%) | 50 (15.3%) | 27 (26.2%) | .012 |

| Self-rated heath | ||||

| Excellent/very good | 180 (42.1%) | 140 (42.8%) | 40 (39.6%) | .568 |

| Good/fair/poor | 248 (57.9%) | 187 (57.2%) | 61 (60.4%) | |

| PHQ-9 total score (0–27) | 8.48 (6.39) | 8.47 (6.47) | 8.50 (6.17) | .966 |

| Perceived stress score (4 items, composite score 0–16) | 8.49 (2.71) | 8.34 (2.81) | 8.96 (2.31) | .025 |

| Self-perceived excessive drinking | ||||

| Yes | 95 (45.5%) | 137 (42.0%) | 58 (56.3%) | .011 |

| Use of drugs other than marijuana, cocaine, or heroin in past 30 days | ||||

| 0 uses | 413 (96.5%) | 316 (97.2%) | 97 (94.2%) | .142 |

| ≥1 use | 15 (3.5%) | 9 (2.8%) | 6 (5.8%) | |

| Lifetime detox admissions | 2.03 (6.21) | 1.68 (4.70) | 3.15 (9.46) | .132 |

Note. Summary statistics are given as mean (SD) for continuous variables and number (percent) for categorical variables. Significant associations are in bold.

Table 2.

Univariate Associations Between Demographic, Smoking, and Health-Related Variables and Retention at Week 26

| Characteristic | Total (n = 430) | Completed week 26 (n = 324) | Did not complete week 26 (n = 106) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 44.35 (9.96) | 45.32 (9.58) | 41.38 (10.55) | <.001 |

| Male | 321 (74.7%) | 244 (75.3%) | 77 (72.6%) | .584 |

| Race | ||||

| African American/Black | 242 (56.3%) | 192 (59.3%) | 50 (47.2%) | .072 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 153 (35.6% | 109 (33.6%) | 44 (41.5%) | |

| Other race | 35 (8.1%) | 23 (7.1%) | 12 (11.3%) | |

| Monthly income | ||||

| <$400 | 293 (68.1%) | 219 (67.6%) | 74 (69.8%) | .579 |

| $400–799 | 87 (20.2%) | 69 (21.3%) | 18 (17.0%) | |

| ≥$800 | 50 (11.6%) | 36 (11.1%) | 14 (13.2%) | |

| Homelessness duration | ||||

| <6 months | 143 (33.3%) | 113 (35.0%) | 30 (28.3%) | .009 |

| 6–12 months | 72 (16.8%) | 44 (13.6%) | 28 (26.4%) | |

| ≥1 year | 214(49.9%) | 166 (51.4%) | 48 (45.3%) | |

| Homeless episodes in past 3 years | ||||

| 1 | 185 (43.2%) | 127 (39.4%) | 58 (54.7%) | .023 |

| 2 or 3 | 152 (35.5%) | 122 (37.9%) | 30 (28.3%) | |

| ≥4 | 91 (21.3%) | 73 (22.7%) | 18 (17.0%) | |

| Smoking characteristics | ||||

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 19.25 (13.73) | 19.04 (12.86) | 19.88 (16.18) | .628 |

| Time to 1st cigarette | ||||

| ≤30 min | 374 (87.0%) | 281 (86.7%) | 93 (87.7%) | .789 |

| >30 min | 56 (13.0%) | 43 (13.3%) | 13 (12.3%) | |

| Time of last quit attempt >24 hr | ||||

| Never quit before | 81 (19.7 %) | 62 (20.1%) | 19 (18.3%) | .725 |

| ≤12 months ago | 153 (37.1%) | 111 (36.0%) | 42 (40.4%) | |

| >12 months ago | 178 (43.2%) | 135 (43.8%) | 43 (41.3%) | |

| Importance of quitting (1–10 scale) | 9.07 (1.63) | 9.00 (1.69) | 9.27 (1.40) | .103 |

| Confidence to quit (1–10 scale) | 7.27 (2.43) | 7.28 (2.41) | 7.23 (2.52) | .851 |

| Physical and mental health | ||||

| Have healthcare coverage | ||||

| No | 77 (17.9%) | 55 (17.0%) | 22 (20.8%) | .378 |

| Self-rated heath | ||||

| Excellent/very good | 180 (42.1%) | 138 (42.9%) | 42 (39.6%) | .559 |

| Good/fair/poor | 248 (57.9%) | 184 (57.1%) | 64 (60.4%) | |

| PHQ-9 total score (0–27) | 8.48 (6.39) | 8.95 (6.49) | 7.06 (5.88) | .008 |

| Perceived stress score (4 items, composite score 0–16) | 8.49 (2.71) | 8.48 (2.83) | 8.50 (2.32) | 0.946 |

| Self-perceived excessive drinking | ||||

| Yes | 95 (45.5%) | 142 (44.0%) | 53 (50.0%) | 0.279 |

| Use of drugs other than marijuana, cocaine, or heroin in past 30 days | ||||

| 0 uses | 413 (96.5%) | 314 (97.5%) | 99 (93.4%) | 0.046 |

| ≥1 use | 15 (3.5%) | 8 (2.5%) | 7 (6.6%) | |

| Lifetime detox admissions | 2.03 (6.21) | 1.58 (4.32) | 3.43 (9.88) | 0.065 |

Note. Summary statistics are given as mean (SD) for continuous variables and number (percent) for categorical variables. Significant associations are in bold.

Associations that were significant in the univariate analysis remained significant in the multivariate analysis. In addition, greater number of lifetime admissions to detox was significantly associated with retention at week 26 in the multivariate but not the univariate model. Results of the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variables Significantly Associated With Retention at Weeks 8 and 26 in Multivariate Model

| Characteristic | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 8 | |||

| Greater age | 1.035 | 1.012–1.059 | .003 |

| Have healthcare coverage | 1.806 | 1.043–3.127 | .035 |

| Perceived stress score | 0.916 | 0.844–0.995 | .039 |

| Self-perceived excessive drinking | 0.506 | 0.318–0.807 | .004 |

| Week 26 | |||

| Greater age | 1.044 | 1.019–1.069 | <.001 |

| Homelessness duration (reference: 6–12 months) | .001a | ||

| <6 months | 3.665 | 1.848–7.266 | .003 |

| ≥1 year | 2.486 | 1.329–4.649 | .299 |

| Homeless episodes in past 3 years (reference: single episode) | .034a | ||

| 2 or 3 episodes | 2.016 | 1.166–3.485 | .103 |

| ≥4 episodes | 1.656 | 0.849–3.231 | .633 |

| Higher PHQ-9 score | 1.063 | 1.020–1.108 | .004 |

| Use of recreational drugs other than marijuana, cocaine, or heroin (vs. no use) | 0.273 | 0.081–0.916 | .036 |

| Greater number of detox admissions | 0.938 | 0.899–0.979 | .003 |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.aGlobal test p value.

The most commonly cited reason for missing appointments was that participants forgot or there was a miscommunication about the time. Other common reasons included conflicts with other appointments, work, or school and lack of transportation. A majority of respondents said that phone calls were the most helpful type of reminder. The main reasons given for finishing the program were desire to quit, incentives, and positive interactions with the staff. Visa cards and bus tokens were the most preferred compensation items.

Discussion

We found that it is possible to successfully retain homeless individuals in a smoking cessation study. Our retention rate of 75% compares favorably with other smoking cessation studies conducted with low-income and minority housed populations. One study that compared MI plus nicotine patch to brief physician advice plus nicotine patch in low-income smokers had a retention rate of 50% at 6 months and 44% at 12 months.39 Two studies involving Latino smokers achieved retention rates of 71% and 81% at 3 months and 8 weeks, respectively.40,41 Another study of smokers with a history of depression had a retention rate of 66% at 6 weeks.42

It is notable that retention rates did not differ significantly between the MI and SC arms. In a review of strategies to enhance retention in community-based studies, one suggestion made by Davis and colleagues1 was to offer an appealing control treatment. In the Power to Quit study, both treatment groups were given nicotine patches due to ethical concerns about withholding treatment from a disadvantaged group and practical consideration about the possibility of participants in different study arms sharing patches. Since participants cited desire to quit as one of the top motivators for completing the study, giving patches to the control arm may have increased retention in that group.

Repeated attempts to contact participants also likely increased retention, since a majority of participants felt that phone calls were the most helpful type visit reminder. Even if participants missed visits, the staff continued trying to reach them on a weekly basis using multiple means of communication. This persistence was critical as participants would intermittently run out of minutes on their phones. It was not uncommon for participants who missed appointments to complete later study visits. As shown in Figure 1, attendance dropped during the retention weeks but rebounded at week 26. The larger compensation offered at the final visit may have also contributed to this trend.

We identified a number of variables associated with study retention. Greater age was significantly associated with retention at both week 8 and 26. Other studies of attrition have found the same result.2,10 One possible explanation for this is that younger people may be more mobile and consequently more difficult to contact.43 In contrast, other studies have found that depressive symptoms are associated with decreased retention,40,42,44 while in this study, a higher PHQ-9 score was associated with increased retention at week 26. For a population that often has difficulty accessing care,45 the contact with study staff may have been therapeutic, even though mental health was not the focus of the study. We also found that having health care coverage was associated with increased study completion. This may have occurred because people with health care coverage are more accustomed to making appointments and working with health care providers and therefore may adapt more readily to the study setting.

The association between high baseline perceived stress and decreased retention at week 8 is not surprising and is consistent with other trials.44 However, this association did not persist at week 26. It is possible that as participants grew accustomed to attending study appointments and developed rapport with the staff the effects of stress and prior experience with health care settings were mitigated. By contrast, alcohol and drug use had a consistent negative impact on retention although the specific variables significantly associated with retention were different at week 8 and 26. This association is consistent with prior research10,46 and raises the question of whether studies that address both smoking and use of other drugs might be more successful, at least in terms of program completion.

We found that multiple homeless episodes were associated with increased retention. In addition, participants who had been homeless 6–12 months were less likely to complete the study than those homeless for less than 6 months or for more than 1 year. Other studies have found that people who have been homeless longer are more likely to have health insurance45 and complete the hepatitis B vaccine series.10 One explanation for this is that those who have been homeless longer have had time to adapt and learn about the services available to them. It is unclear, however, why intermediate duration of homelessness was associated with decreased retention in this study.

A number of participant characteristics that have been associated with retention in other studies (e.g., gender, marital status, income, heaviness of smoking, nicotine dependence) were not predictive in this study.2,10,46 This is perhaps not surprising given the amount of heterogeneity in retention research, both in the factors associated with retention and the direction of those associations. While some studies have found increased motivation and confidence to quit,12,40 prior quit attempts,12 and worse health status10 to be predictive of study completion, other studies have found the opposite relationships,41,42 and we found no relationship at all. The lack of a relationship between motivation to quit and retention has important implications, since motivation, unlike demographic characteristics, is something that can be addressed within a smoking cessation program. However, almost all participants in this study expressed strong motivation to quit, which may have obscured any association of motivation with study completion. And as previously noted, many participants cited a desire to quit smoking as one of their main reasons for continuing in the program. It is possible that participant characteristics associated with retention vary depending on study design; this is an issue that requires more study.

This study has some limitations. First of all, it is an exploratory secondary analysis in a study designed and powered for a primary outcome of smoking cessation. We therefore examined a large number and variety of variables, increasing the risk of type I error, although many of the factors identified were significant even using p = .01 as a cutoff for significance. It should also be noted that the odds ratios for many variables associated with retention were quite small. Since there was little variation in overall retention between the treatment arms, we also did not analyze factors associated with retention in each treatment arm separately. Generalizability of the study may be limited by the fact that participants were drawn from the Minneapolis-Saint Paul metro area and participants were predominantly male and of either African American or white race

Conclusion

It is possible to successfully retain homeless adults in a smoking cessation study if the study is designed to accommodate participants’ needs and interests and if sufficient effort is invested in maintaining contact with participants. Future studies that address some of the issues that increased risk of attrition such as alcohol and drug use, high life stress, and lack of health insurance have the potential to further improve retention. Demonstrated success at retention, in turn, may encourage more researchers to direct their attention toward improving health care for this severely underserved group.

Funding

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL081522); National Cancer Institute (U54CA153603); National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA022445); National Cancer Institute (CA112441); National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK071065) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR000114 to HG). XL received support from the University Masonic Cancer Center, Biostatistics Core, supported by the National Cancer Institute (P39CA077598).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Warren, PhD, and project staff Sharae Walker, Bonnie Houg, R’Gina Sellers, Casey Tuck, Abimbola Olayinka, Carolyn Warner, Carolyn Bramante, MD, Julia Davis, Pravesh Napaul, and Brandi White for their assistance with implementation of the project. The authors further acknowledge the directors of participating shelters, Dorothy Day Center, Our Savior’s Shelter, Listening House, Union Gospel Mission, Naomi Family Center, and People Serving People and, finally, express gratitude to the members of the CAB and the study participants.

References

- 1. Davis LL, Broome ME, Cox RP. Maximizing retention in community-based clinical trials. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Snow WM, Connett JE, Sharma S, Murray RP. Predictors of attendance and dropout at the Lung Health Study 11-year follow-up. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young AF, Powers JR, Bell SL. Attrition in longitudinal studies: who do you lose? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30:353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Conover S, Berkman A, Gheith A, et al. Methods for successful follow-up of elusive urban populations: an ethnographic approach with homeless men. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1997;74:90–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ball SA, Cobb-Richardson P, Connolly AJ, Bujosa CT, O’neall TW. Substance abuse and personality disorders in homeless drop-in center clients: symptom severity and psychotherapy retention in a randomized clinical trial. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, Felix A, Tsai WY, Wyatt RJ. Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a ‘‘critical time’’ intervention after discharge from a shelter. Am J Pub Health. 1997;87:256–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burns MN, Lehman KA, Milby JB, Wallace D, Schumacher JE. Do PTSD symptoms and course predict continued substance use for homeless individuals in contingency management for cocaine dependence? Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:588–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kashner TM, Rosenheck R, Campinell AB, et al. Impact of work therapy on health status among homeless, substance-dependent veterans: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kertesz SG, Madan A, Wallace D, Schumacher JE, Milby JB. Substance abuse treatment and psychiatric comorbidity: do benefits spill over? Analysis of data from a prospective trial among cocaine-dependent homeless persons. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2006;1:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nyamathi A, Liu Y, Marfisee M, et al. Effects of a nurse-managed program on hepatitis A and B vaccine completion among homeless adults. Nurs Res. 2009;58:13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reback CJ, Peck JA, Dierst-Davies R, Nuno M, Kamien JB, Amass L. Contingency management among homeless, out-of-treatment men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shelley D, Cantrell J, Wong S, Warn D. Smoking cessation among sheltered homeless: a pilot. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:544–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Slesnick N, Kang MJ. The impact of an integrated treatment on HIV risk behavior among homeless youth: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med. 2008;31:45–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baggett TP, Rigotti NA. Cigarette smoking and advice to quit in a national sample of homeless adults. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Connor SE, Cook RL, Herbert MI, Neal SM, Williams JT. Smoking cessation in a homeless population: there is a will, but is there a way? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:369–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gelberg L, Linn LS. Assessing the physical health of homeless adults. JAMA. 1989;262:1973–1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee TC, Hanlon JG, Ben-David J, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in homeless adults. Circulation. 2005;111:2629–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sachs-Ericsson N, Wise E, Debrody CP, Paniucki HB. Health problems and service utilization in the homeless. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1999;10:443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Szerlip MI, Szerlip HM. Identification of cardiovascular risk factors in homeless adults. Am J Med Sci. 2002;324:243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000;283:2152–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O’Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Snyder LD, Eisner MD. Obstructive lung disease among the urban homeless. Chest. 2004;125:1719–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arnsten JH, Reid K, Bierer M, Rigotti N. Smoking behavior and interest in quitting among homeless smokers. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Butler J, Okuyemi KS, Jean S, Nazir N, Ahluwalia JS, Resnicow K. Smoking characteristics of a homeless population. Subst Abus. 2002;23:223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okuyemi KS, Caldwell AR, Thomas JL, et al. Homelessness and smoking cessation: insights from focus groups. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baggett TP, Anderson R, Freyder PJ, et al. Addressing tobacco use in homeless populations: a survey of health care professionals. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:1650–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bryant J, Bonevski B, Paul C, McElduff P, Attia J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of behavioural smoking cessation interventions in selected disadvantaged groups. Addiction. 2011;106:1568–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okuyemi KS, Thomas JL, Hall S, et al. Smoking cessation in homeless populations: a pilot clinical trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marcellus LM. Are we missing anything? Pursuing research on attrition. Can J Nurs Res. 2004;36:82–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goldade K, Whembolua GL, Thomas J, et al. Designing a smoking cessation intervention for the unique needs of homeless persons: a community-based randomized clinical trial. Clin Trials. 2011;8:744–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okuyemi KS, Goldade K, Whembolua GL, et al. Motivational interviewing to enhance nicotine patch treatment for smoking cessation among homeless smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2013;108:1136–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wilder Research Center. Homelessness in Minnesota 2003: Key Facts From Survey of Minnesotans Without Permanent Housing. 2004. http://www.wilder.org/Wilder-Research/Publications/Studies/Homelessness%20in%20Minnesota,%202003%20Study/Homeless%20in%20Minnesota%202003%20-%20Key%20Facts%20from%20the%20Survey%20of%20Minnesotans%20Without%20Permanent%20Housing.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okuyemi KS, Goldade K, Whembolua GL, et al. Smoking characteristics and comorbidities in the power to quit randomized clinical trial for homeless smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rost K, Burnam MA, Smith GR. Development of screeners for depressive disorders and substance disorder history. Med Care. 1993;31:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 20), 22–33; quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bock BC, Papandonatos GD, de Dios MA, et al. Tobacco cessation among low-income smokers: motivational enhancement and nicotine patch treatment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;16:413–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee CS, Hayes RB, McQuaid EL, Borrelli B. Predictors of retention in smoking cessation treatment among Latino smokers in the Northeast United States. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nevid JS, Javier RA, Moulton JL., 3rd Factors predicting participant attrition in a community-based, culturally specific smoking-cessation program for Hispanic smokers. Health Psychol. 1996;15:226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Curtin L, Brown RA, Sales SD. Determinants of attrition from cessation treatment in smokers with a history of major depressive disorder. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000;14:134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC. Residential mobility among patients in the VA health system: associations with psychiatric morbidity, geographic accessibility, and continuity of care. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moser DK, Dracup K, Doering LV. Factors differentiating dropouts from completers in a longitudinal, multicenter clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2000;49:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weber M, Thompson L, Schmiege SJ, Peifer K, Farrell E. Perception of access to health care by homeless individuals seeking services at a day shelter. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. El-Khorazaty MN, Johnson AA, Kiely M, et al. Recruitment and retention of low-income minority women in a behavioral intervention to reduce smoking, depression, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]