Abstract

Observation of the activation and inhibition of angiogenesis processes is important in the progression of cancer. Application of targeting peptides, such as a small peptide that contains adjacent L-arginine (R), glycine (G) and L-aspartic acid (D) residues can afford high selectivity and deep penetration in vessel imaging. To facilitate deep tissue vasculature imaging, probes that can be excited via two-photon absorption (2PA) in the near-infrared (NIR) and subsequently emit in the NIR are essential. In this study, the enhancement of tissue image quality with RGD conjugates was investigated with new NIR-emitting pyranyl fluorophore derivatives in two-photon fluorescence microscopy. Linear and nonlinear photophysical properties of the new probes were comprehensively characterized; significantly the probes exhibited good 2PA over a broad spectral range from 700–1100 nm. Cell and tissue images were then acquired and examined, revealing deep penetration and high contrast with the new pyranyl RGD-conjugates up to 350 μm in tumor tissue.

Introduction

Intravital imaging techniques have provided unprecedented insight into tumor microcirculation and microenvironment, allowing quantitative evaluation of tumor blood vasculature, functional lymphatics, and other microenviroment characterization.1 These techniques are supported by powerful optical imaging methods, such as two-photon fluorescence microscopy (2PFM). 2PFM is able to achieve high resolution, deep penetration images by using near infrared (NIR) short-pulsed excitation light, and has been applied in many areas, including cancer research.1–2

Angiogenesis, the formation of new vessels from existing microcapillaries, is an important factor in the progression of cancer. It is stimulated when malignant tumor tissues require nutrients and oxygen, stimulating chemical signals from cancer cells, triggering tumor growth and metastasis.3 Therefore, it is of great importance to observe the activation and inhibition of angiogenesis processes. It was reported that angiogenesis is regulated by integrins, which are member of a family of cell surface receptors.4 Among the integrin proteins, αvβ3 integrin plays a key role in endothelial cell survival and migration and is expressed in response to angiogenic growth factors in tumor progression,5 indicating αvβ3 integrin can be a target for tumor angiogenesis. Cyclic RGD containing peptides (c-RGDfK) bind specifically to αvβ3 integrin.6 As a result, both linear and cyclic RGD-peptides, selective for αvβ3 integrins, have been used for various purposes such as targeting drugs specific to tumor vasculature.7

Many organic fluorescent probes are hydrophobic and difficult to dissolve in water or other polar solvents such as DMSO, greatly limiting their utility in biological application. To overcome this obstacle, hydrophilic groups such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) can be introduced into the molecular structure to increase water solubility. In addition, different delivery systems can also be employed in the encapsulation of probes, such as micelles, nanoparticles, and polymers.8

The 4H-pyran-4-ylidene structures have attracted a fair amount of attention because of their interesting optical properties. This moiety can function as an electron acceptor group with good photochemical stability. Substitution can take place at positions 2 and 6, generating a D-π-A or D-π-A-π-D structure. 4H-Pyran-4-ylidene derivatives are widely used in organic light-emitting diodes9, fluorescence bioimaging8b, 8c, 10, and pH sensors11. A fluorene-based di-substituted 4H-pyran-4-ylidene derivative was reported with good solubility in organic solvents. Although it exhibited poor solubility in polar solvents, it still enabled creation of high quality images in biological systems by encapsulation in silica nanoparticles.8b Inspired by these results, three new pyranyl structures were synthesized. Pyranylidenes 1 and 2 were conjugated with c-RGDfK for vessel targeting, whereas pyranylidene 3 was encapsulated in organic nanoparticles for comparison. Linear and nonlinear photophysical properties in different solvents were comprehensively characterized to understand the nature and potential of the new probes. Cell and tissue images support integrin-dependent cell uptake of the probes. Two-photon fluorescence tissue imaging was achieved at 350 μm into a solid tumor with the RGD-conjugated pyranyl probes.

Materials and Methods

Cyclic peptide (Ar-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Lys) c(RGDfK) was purchased from Peptides International, Inc. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Aldrich or Acros Organics, and used as received unless otherwise noted. THF was purified by distillation over sodium and benzophenone under nitrogen before use. CH3CN was dried over calcium hydride. Synthetic details of intermediate compounds are described in the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI). Reactions were performed under a dry nitrogen atmosphere using standard vacuum line techniques. 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic measurements were performed using Varian VNMRS 500 and Bruker Avance III 400 spectrometers at 500 or 400 MHz respectively, for 1H (referenced to TMS at δ = 0.0 ppm) and 125 MHz for 13C (referenced to CDCl3 at δ = 77.0 ppm). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analysis was performed in the Department of Chemistry, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Synthesis of (E)-3-(2-(2-(4-(dicyanomethylene)-6-methyl-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid (H)

A mixture of 3-(2-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-7-formyl-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid, (G, 1.18 g, 2.14 mmol), and commercial 2,6-dimethyl-4-dicyanomethylene-4H-pyran (2.94 g, 17.12 mmol) were dissolved in acetonitrile (200 mL). After adding piperidine (1 mL) slowly via syringe while stirring, the reaction mixture was refluxed for 36 h. The solution color gradually changed from light yellow to deep red. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and purification was carried out by silica gel column chromatography using first hexanes/ethyl acetate (1:1) as eluent, then ethyl acetate/MeOH (9:1) to obtain a red solid (1.2 g, 80% yield). mp = 210–211 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.61 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.55 – 7.42 (m, 4H), 7.35 – 7.21 (m, 4H), 7.21 – 6.93 (m, 8H), 6.84 – 6.65 (m, 2H), 6.55 (dd, J = 2.1, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (m, 2H), 3.26 (hept, J = 5.4, 4.9 Hz, 2H), 3.03 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.96 – 2.77 (m, 2H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.38 – 2.11 (m, 4H), 1.63 (ddt, J = 22.4, 16.5, 11.3 Hz, 2H), 1.14 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 177.92, 177.90, 161.99, 159.40, 156.34, 150.66, 149.28, 148.60, 147.52, 143.35, 138.49, 133.98, 132.69, 129.35, 127.83, 124.54, 123.27, 122.96, 122.39, 121.21, 119.69, 117.83, 116.92, 115.19, 115.08, 106.90, 106.41, 70.08, 69.66, 67.39, 66.58, 58.94, 52.33, 38.99, 35.09, 29.24, 19.99, 15.08. HRMS (ESI, [M+H]+) calcd for C45H41N3O5+ 704.3119, found. 704.3101.

Synthesis of 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl-(E)-3-(2-(2-(4-(dicyanomethylene)-6-methyl-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoate (1)

E)-3-(2-(2-(4-(Dicyanomethylene)-6-methyl-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid (H, 0.2 g, 0.28 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (3.5 mL) under N2; then, N-hydroxysuccinimide (0.04 g, 0.34 mmol) was added to the mixture at room temperature. N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (0.063 g) was added to the mixture and stirred at room temperature for 36 h. The mixture was then filtered and diluted with 3–4 volumes of ether to precipitate the product. The solid was collected by filtration, redissolved in a minimum volume of DMF, and then reprecipitated by addition of ether. The solid was collected and dried to afford 0.2 g of a red solid (90% yield). mp = 124–125 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.62 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.57 – 7.48 (m, 4H), 7.34–7.22 (m, 4H), 7.18 – 7.08 (m, 5H), 7.08 – 7.01 (m, 3H), 6.79 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (dt, J = 1.5, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 3.47 – 3.32 (m, 4H), 3.26 – 3.19 (m, 2H), 3.15 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.02 – 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.78 (s, 4H), 2.48 – 2.38 (s, 3H), 2.38 – 2.19 (m, 2H), 1.72 – 1.50 (m, 2H), 1.13 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.38, 169.11, 168.32, 162.12, 159.41, 156.40, 149.76, 148.91, 148.40, 147.41, 143.19, 138.31, 133.67, 132.99, 129.44, 128.14, 124.76, 123.51, 122.80, 122.34, 121.36, 119.84, 117.35, 117.28, 115.21, 115.10, 107.04, 106.41, 70.10, 69.65, 67.29, 66.58, 58.84, 52.17, 38.94, 34.25, 25.54, 19.99, 15.09. HRMS (MALDI-DTL, [M]+) calcd for C49H44N4O7 800.3210, found. 800.3204.

Synthesis of Fluorene-RGD Conjugate (1a)

Fluorene-NHS 1 (22 mg, 0.027 mmol) and c(RGDfK) (15 mg, 0.024 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (1.5 mL), and the solution stirred for 24 h under nitrogen at room temperature. The mixture was then diluted with 4 volumes of ether to precipitate the dye. The solid was collected by filtration, redissolved in a minimum volume of DMF, and then reprecipitated by addition of ether. The solid was collected and dried to afford 26 mg of a red solid (82% yield). mp = 203–204 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.19 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 2H), 8.12 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.81 – 7.59 (m, 5H), 7.54 (q, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (dd, J = 16.1, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.34 – 7.24 (m, 5H), 7.24 – 7.10 (m, 7H), 7.14 – 7.01 (m, 9H), 6.94 (ddd, J = 8.2, 2.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (dd, J = 2.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 4.59 (s, 2H), 4.46 (s, 1H), 4.22 (s, 4H), 4.13 (dd, J = 16.3, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 3.32 – 3.19 (m, 6H), 3.15 – 3.01 (m, 5H), 2.87 – 2.80 (m, 2H), 2.73 (dtd, J = 24.7, 9.5, 5.9 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 3H), 2.23 (s, 4H), 2.12 (tt, J = 13.5, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 1.64 (s, 3H), 1.49 – 1.33 (m, 2H), 1.22 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO) δ (ppm): 172.42, 171.80, 171.77, 171.80, 171.77, 171.27, 170.88, 164.57, 160.53, 157.15, 157.12, 151.47, 150.02, 148.05, 147.65, 142.73, 138.49, 134.92, 133.73, 129.97, 129.39, 128.43, 126.45, 124.21, 123.54, 122.84, 122.11, 120.29, 119.02, 118.43, 115.95, 107.19, 106.27, 69.78, 69.58, 67.13, 65.90, 56.03, 55.27, 52.64, 49.06, 43.37, 41.05, 39.96, 39.88, 39.79, 39.62, 39.51, 39.46, 38.85, 38.71, 30.22, 25.68, 24.95, 19.86, 15.50. HRMS (MALDI-DTL, [M+H]+) calcd for C72H80N12O11+ 1289.6149, found. 1289.6109.

Synthesis of 3-(2-((E)-2-(4-(dicyanomethylene)-6-((E)-2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-di(3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27,30-decaoxadotriacontyl)-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid (K)

A mixture of (E)-3-(2-(2-(4-(dicyanomethylene)-6-methyl-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid (H, 0.12 g, 0.175 mmol), and 7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-di(3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27,30 decaoxadotriacontyl)-9H-fluorene-2-carbaldehyde (J, 0.15 g, 0.115 mmol) were dissolved in acetonitrile (15 mL). After adding piperidine (0.5 mL) slowly via syringe while stirring, the reaction mixture was refluxed for 48 h. The solution color gradually changed from light yellow to deep red. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and purification was carried out by silica gel column chromatography using first CH2Cl2/MeOH (95:15) as eluent, then CH2Cl2/MeOH (90:10) to obtain red solid (0.12 g, 58% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.61 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.57 – 7.44 (m, 8H), 7.34 – 7.18 (m, 9H), 7.18 – 6.94 (m, 16H), 6.80 – 6.66 (m, 2H), 6.54 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 76H), 3.41 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.24 (hept, J = 5.5 Hz, 6H), 2.87 (ddq, J = 24.6, 9.7, 5.6, 4.7 Hz, 4H), 2.39 – 2.09 (m, 4H), 1.81–1.45 (m, 6H), 1.13 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 176.99, 173.20, 161.96, 159.35, 156.30, 150.45, 149.03, 148.67, 147.49, 143.35, 138.36, 133.96, 132.74, 129.38, 127.78, 124.60, 123.35, 122.93, 122.52, 121.23, 119.72, 117.70, 117.07, 115.14, 115.05, 106.96, 106.41.70.56, 70.50, 70.43, 70.31, 70.10, 69.67, 69.01, 67.34, 66.58, 63.46, 59.01, 58.97, 52.32, 50.24, 39.09, 34.65, 29.68, 15.09. HRMS-MALDI-DTL: High resolution MS shows a series of ions centered around m/z 1955 [C75H66N4O5(C2H4O)20]+ which are fragments related to the various ethoxylate oligomers that differ by Δm/z 44, an ethoxy unit.

Synthesis of 2,5-dioxopyrrolidin-1-yl 3-(2-((E)-2-(4-(dicyanomethylene)-6-((E)-2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-di(3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27,30-decaoxadotriacontyl)-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoate (2)

(3-(2-((E)-2-(4-(Dicyanomethylene)-6-((E)-2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-di(3,6,9,12,15,18,21,24,27,30-decaoxadotriacontyl)-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid (K, 50 mg, 0.025 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (3 mL) under N2; then, N-hydroxysuccinimide (5 mg, 0.043 mmol) was added to the mixture at room temperature. Next N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (8 mg, 0.043 mmol) was added to the mixture and stirred at room temperature for 36 h. The mixture was then filtered and redissolved in a minimum volume of DMF, and then filtered again. The product was dried under vacuum to afford red oil (45 mg, 85% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.60 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.56 – 7.43 (m, 8H), 7.34 – 7.18 (m, 9H), 7.17 – 6.943 (m, 16H), 6.82 – 6.69 (m, 2H), 6.58 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 76H), 3.51 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.24 (hept, J = 5.5 Hz, 6H), 2.87 (m, 8H), 2.39 – 2.09 (m, 4H), 1.81–1.45 (m, 6H), 1.10 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 173.20, 169.88, 169.47, 161.96, 159.35, 156.35, 150.42, 149.00, 148.63, 147.66, 143.32, 138.38, 133.95, 132.72, 129.41, 127.82, 124.74, 123.32, 122.96, 122.48, 121.22, 119.71, 117.68, 117.05, 115.18, 115.09, 106.94, 106.39, 70.59, 70.54, 70.47, 70.39, 70.09, 69.63, 69.01, 67.31, 66.54, 63.43, 59.01, 52.28, 50.24, 39.05, 34.65, 29.60, 25.55, 15.07. HRMS-MALDI-DTL: High resolution MS shows a series of ions centered around m/z 2052 [C79H69N5O7(C2H4O)20]+ which are fragments related to the various ethoxylate oligomers that differ by Δm/z 44, an ethoxy unit.

Synthesis of Fluorene-RGD Conjugate (2a)

Fluorene-NHS 2 (20 mg, 0.010 mmol) and c(RGDfK) (5 mg, 0.008 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (1.5 mL), and the solution stirred for 24 h under nitrogen at room temperature. Solvent was removed under vacuum, and crude product was then passed through a size exclusion column (12 cm length, Bio-Rad Econo-Pac 10DG, MWCO) in pure water to allow collection of pure RGD conjugate fractions, yielding a red oil (15 mg, 60% yield). HRMS-MALDI-DTL: High resolution MS shows a series of ions centered around m/z 2540 [C102H105N13O11(C2H4O)20]+ which are fragments related to the various ethoxylate oligomers that differ by Δm/z 44, an ethoxy unit.

Synthesis of (E)-2-(2-(2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-ylidene)malononitrile (N)

7-(Diphenylamino)-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluorene-2-carbaldehyde (M, 0.2 g, 0.37 mmol) was mixed with the pyran (0.255 g, 1.48 mmol) and dissolved in 100 mL distilled CH3CN. Piperidine (0.15 mL) was added and the reaction mixture refluxed for 72 h to yield reddish solution. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the crude product purified on silica gel using hexanes/ethyl acetate (7:3) to yield brown solid (0.25 g, 48%) δ H (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) 0.36 – 0.86 (10 H, m), 0.84 – 1.26 (12 H, m), 1.61 – 1.94 (4 H, tt, J 13.2, 6.8), 2.16 – 2.66 (3 H, s), 4.98 – 5.39 (1 H, d, J 0.7), 6.44 – 6.51 (1 H, d, J 1.5), 6.61 – 6.67 (1 H, m), 6.67 – 6.72 (0 H, s), 6.91 – 7.00 (3 H, td, J 8.4, 8.0, 1.7), 7.01 – 7.09 (4 H, m), 7.13 – 7.24 (6 H, m), 7.34 – 7.39 (1 H, s), 7.39 – 7.45 (1 H, d, J 8.5), 7.45 – 7.52 (1 H, m), 7.52 – 7.59 (1 H, d, J 7.9). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.31, 159.96, 156.74, 153.25, 151.91, 148.55, 148.14, 144.23, 139.29, 135.20, 132.82, 129.63, 127.88, 124.56, 123.53, 123.29, 122.20, 121.38, 119.96, 119.01, 116.94, 115.57, 107.17, 106.80, 59.24, 55.49, 40.58, 31.89, 29.98, 24.17, 22.93, 20.38, 14.42

Synthesis of 6-(4-((E)-2-(4-(dicyanomethylene)-6-((E)-2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy)hexanoic acid (3)

The (E)-2-(2-(2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-ylidene)malononitrile (N, 0.12 g, 0.179 mmol) and 6-(4-formyl-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy)hexanoic acid (Q, 0.064 g, 0.215 mmol) were dissolved in distilled CH3CN (20 mL). Piperidine (0.1 mL) was then added. The reaction mixture refluxed at 130 °C for 5 d. The crude product was purified on silica gel using methanol/ethyl acetate (1:9) to yield red solid (45mg, 26%) δH (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) 0.56 – 1.00 (10 H, m), 0.99 – 1.43 (18 H, m), 1.51 – 1.67 (3 H, qd, J 8.5, 7.3, 2.2), 1.67 – 1.79 (2 H, q, J 7.6), 1.76 – 1.89 (3 H, dt, J 14.0, 6.6), 1.85 – 2.01 (4 H, m), 2.31 – 2.53 (2 H, t, J 7.5), 3.87 – 4.02 (6 H, s), 4.00 – 4.18 (3 H, t, J 6.5), 6.71 – 6.79 (2 H, m), 6.77 – 6.83 (1 H, s), 6.81 – 6.88 (2 H, d, J 5.5), 7.01 – 7.10 (3 H, m), 7.08 – 7.21 (5 H, m), 7.23 – 7.34 (5 H, m), 7.43 – 7.50 (1 H, s), 7.48 – 7.61 (4 H, m), 7.58 – 7.64 (1 H, d, J 4.4), 7.60 – 7.70 (2 H, d, J 8.1). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 179.65, 159.17, 158.68, 156.18, 154.27, 153.24, 151.99, 148.62, 148.14, 144.31, 140.14, 139.22, 138.22, 135.15, 132.91, 130.42, 129.63, 128.19, 124.57, 123.53, 123.31, 121.91, 121.39, 119.94, 119.01, 118.31, 117.45, 115.68, 107.40, 107.16, 105.61,73.65, 70.92, 59.65, 56.70, 55.53, 40.61, 34.28, 31.89, 30.14, 30.07, 29.97, 29.72, 25.79, 24.86, 24.18, 22.91, 14.48, 14.40 HRMS (m/z) [M+H]+ calcd for C63H67N3O6 961.5030; Found 961.5046

Preparation of fluorescent nanoparticles

To prepare the fluorescent organic nanoparticles, 0.1 mL of dye 3 solutions in THF (1 mM) was added dropwise into 9.9 mL of distilled water (to make 3a) or an aqueous solution of Lecithin (25 mg/L, affording 3b). New formed solutions were then stirred vigorously for 20 min.12 Sizes of nanoparticles were measured with Zetasizer Nano-ZS90 (Malvern Instruments). UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded confirming the presence of 3. An aqueous solution was prepared from either 3a or 3b for use as stock solutions.

Photophysical characterization

Linear absorption and fluorescence spectra were recorded using an Agilent 8453, and a PTI QuantaMaster spectrofluorimeter, respectively. The compounds were dissolved in spectroscopic grade solvents, and diluted to ~ 10−6 M in 10 mm quartz cuvettes for measurements. Fluorescence spectra were collected using a red-sensitive PMT and an InGaAs near-infrared detector, both corrected for the responsivities of the detector. Fluorescence quantum yields were calculated via a relative method, using 9,10-diphenylanthracene (ϕf = 0.95) as a reference.13 Excitation anisotropy measurements were performed in viscous solvents (e.g. silicone oil) to impede the molecular rotational relaxations.

Non-linear two-photon absorption (2PA) measurements were collected using the open aperture Z-scan method at room temperature. Samples (≈ 10−2 M) were prepared in DCM (1 and 3) and DMSO (2). This technique utilised a femtosecond laser system (Coherent Inc.),14 wherein the second harmonic output of a Verdi-10 CW Nd:YAG laser seeded a Mira 900 Ti:sapphire laser (repetition rate, f = 76 MHz; average power = 1.1 W; pulse duration, τp ≈ 200 fs), which in turn pumped a Legend Elite USP (f = 1kHz; energy ≈ 3.6 mJ pulse−1; τp ≈ 100 fs). This amplified output was directed into two optical parametric amplifiers (OPerA Solo (OPA), Coherent Inc.), allowing tuning from 0.24 – 20 μm. The output of the first of these OPAs was used for the 2PA measurements.15

Ethics statement

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare regulations and were approved by the Sanford-Burnham Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to execution.

Animal model

0.5 × 106 Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells were injected into the flank of C57B6 mice. After 13 days, 1, 1a, 2 or 2a was injected intravenously at 4×10−8 mol/mouse. 2 h later, PBS was perfused, followed by paraformaldehyde perfusion. Tumors were then dissected from mice and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Cell imaging

Organic nanoparticles 3a and 3b were incubated with HCT-116 cells. The probes 1a and 2a were tested in cultures of U87MG and MCF-7 cell lines. To investigate the efficiency and specificity of RGD-conjugated dye 1a and 2a, three negative control groups were included in the study: 1) The MCF-7 cell line, which is negative for αvβ3 expression16; 2) U87MG cells pre-incubated with free RGD peptide (saturation experiment);3) U87MG cells incubated with 1 or 2 (unconjugated to RGD).

All cells were seeded on poly-D-lysine coated coverslips at the density of 4 × 104 cells/well and incubated for 48 h. Dyes were diluted to 10 μM from stock solutions and added to cells. 1 h later, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution. NaBH4 solution was then applied twice at 1 mg/mL to eliminate autofluorescence. Coverslips were then mounted with ProLong® Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, USA). Images were taken with an Olympus IX-81 DSU microscope.

Tissue imaging

Tumors were dissected 2 h after probe injection. Small sections were cut from the edge of the tumor, where angiogenesis occurred, for 2PFM imaging. Sections were scanned from top to bottom, where the top was the cutting cross section, in order to get a flat surface for depth measurement. Images were obtained with a Leica SP5 II microscope equipped with a Coherent Chameleon Vision S laser source (prechirp compensated, 70 fs, 80 MHz). Tissues were scanned at 900 nm for two-photon imaging, starting from the cutting surface, until fluorescence could no longer be observed. An external non-descanned detector (NDD) was employed to collect fluorescence emission. Scanned images were process with Amira software for 3D visualization. Quantitative analysis of images was performed with Image J software.

Results and Discussion

Synthetic strategy

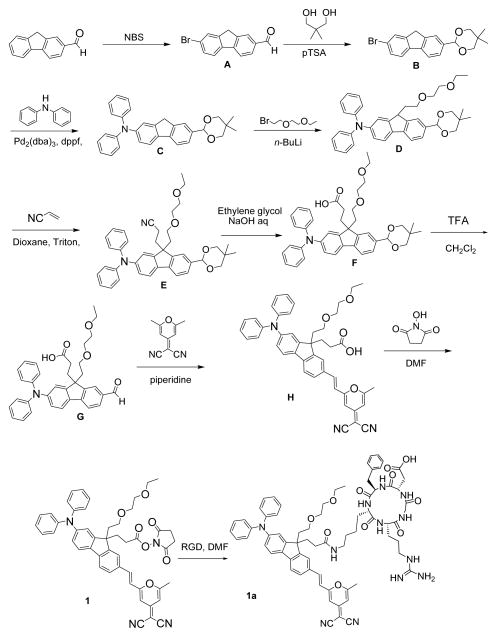

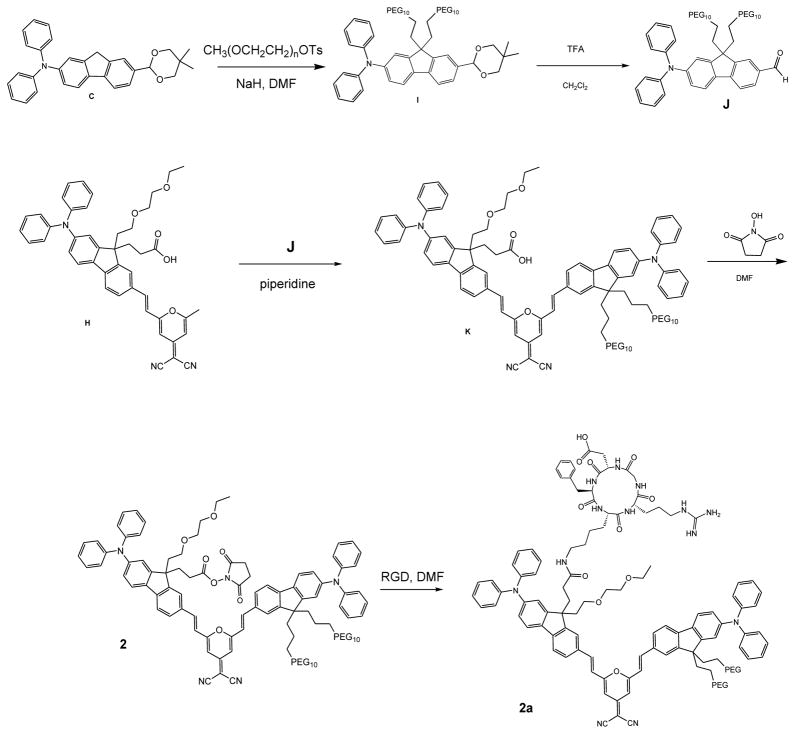

Schemes 1 and 2 depict the design of the two amine reactive probes (1 and 2) and shows our straightforward strategy to incorporate the succinimidyl functionality as a reactive linker on the fluorenyl 9-position for conjunction with the RGDfK peptide. Synthesis of the reactive probes began with the bromination of commercial 9H-fluorene-2-carbaldehyde with NBS in propylene carbonate producing fluorenylcarbaldehyd A, which was then protected with 2,2-dimethyl-1,3-propandiol under acidic conditions to afford 2-(7-bromo-9H-fluoren-2-yl)-5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxane B in 90% yield. Arylamination of acetal B was readily performed using Buchwald–Hartwig amination coupling conditions in the presence of Pd2(dba)3 and 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (dppf) as a ligand to afford C. Monoalkylation of fluorenyl C upon treatment with n-BuLi and 1-bromo-2-(2-methoxyethoxy) ethane in THF at −78 °C provided monoalkylated D in 90% yield. Condensation of acrylonitrile in the presence of benzyltrimethylammonium hydroxide (“Triton B”) as a catalyst with intermediate D via Michael addition reaction provided 3-(2-(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanenitrile (E). Hydrolysis of the nitrile group was achieved with NaOH in ethylene glycol, affording 3-(2-(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-7-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid (F). Efficient hydrolysis of acetal group in F led 3-(2-(diphenylamino)-9-(2-(2-ethoxyethoxy)ethyl)-7-formyl-9H-fluoren-9-yl)propanoic acid (G) was achieved using trifluoroacetic acid. Knoevenagel condensation between aldehyde G and 2-(2,6- dimethypyran- 4-ylidene) malononitrile was carried out in acetonitrile in presence of piperidine, generating pyranylidene H in respectable (80%) yield. Esterification of H with N-hydroxysuccinimide was accomplished in the presence of 1,3- dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), affording the succinimidyl ester pyranylidene 1 in high yield (90%). Conjugation reaction of the activated ester amine reactive probe (1) with cyclicpeptide (Ar-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Lys) c(RGDfK) was conducted in DMF at room temperature for 22 h, affording the pyranylidene fluoren-RGD peptide conjugate (1a) in high yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 1 and 1a.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 2 and 2a.

Increasing the hydrophilicity of the 7-(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)-N,N-diphenyl-9H-fluoren-2-amine (C), was achieved by pegylation of the fluorene in moiety the 9-position via nucleophilic substitution with poly(ethylene glycol) monomethyl ether tosylate in DMF and NaH, producing bispegylated I which was then deprotected in an acid catalyzed process performed using TFA in 1:2 water:CH2Cl2 to yield aldehyde J in high yield. Deprotected J was coupled with a second bi-functional fluorene (H) via Knoevenagel condensation creating the bis-fluorenyl derivative K (Scheme 1). K underwent DCC mediated esterification providing pegylated succinimidyl ester amine reactive probe 2, which was conjugated with c-RGDfK in DMF to obtain pegylated pyranylidene fluorene 2a in 80% yield (Scheme 2).

As indicated in Scheme 3, 6-bromohexanoic acid was esterified in methanol in the presence of a catalytic amount of concentrated H2SO4, accompanied by refluxing the mixture overnight to yield methyl 6-bromohexanoate (O).17 Methyl 6-(4-formyl-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy) hexanoate (P) was synthesized and subsequent ester cleavage was executed to yield 6-(4-formyl-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy) hexanoic acid (Q).18 7-Bromo-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluorene-2-carbaldehyde (L) was synthesized by lithiation of 2, 7-dibromo-9, 9-dihexyl-9H-fluorene with a stoichiometric amount of nBuLi, then reacted with DMF. The reaction mixture was subjected to hydrolysis in water. Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig amination coupling was employed for the arylamination of L in the presence of Cs2CO3 to yield 7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluorene-2-carbaldehyde (M).19 The two key steps that followed involved the Knoevenagel condensation between M and 2-(2,6-dimethyl-4H-pyran-4-ylidene)malononitrile to produce (E)-2-(2-(2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-ylidene)malononitrile (N) and subsequent reaction between N and Q leading to 6-(4-((E)-2-(4-(dicyanomethylene)-6-((E)-2-(7-(diphenylamino)-9,9-dihexyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)vinyl)-4H-pyran-2-yl)vinyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphenoxy)hexanoic acid (3) (Scheme 3). Organic nanoparticles of dicyanopyranyl 3 by slowly adding a THF solution of 3 into distilled water (forming organic nanoparticles designated as 3a) or lecithin aqueous solution to form surfactant stabilized organic nanoparticles (designated as 3b).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 3.

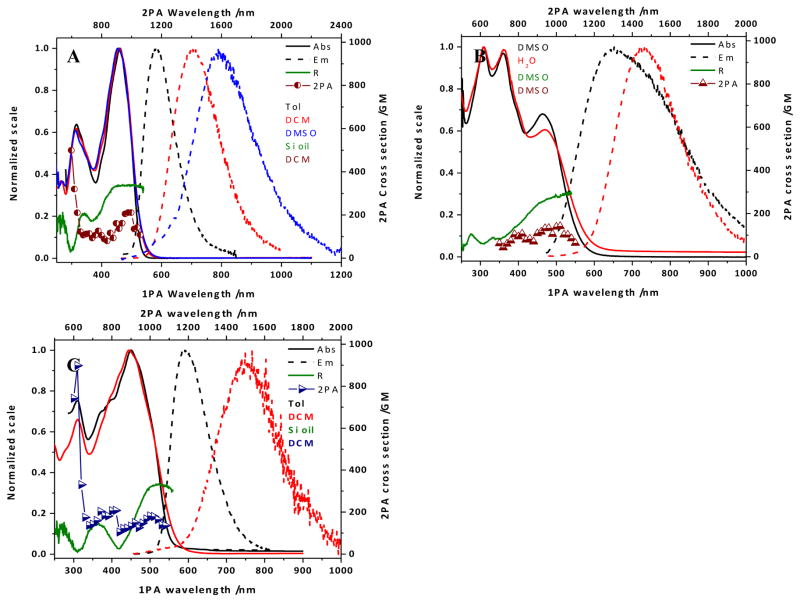

Fluorescence spectra

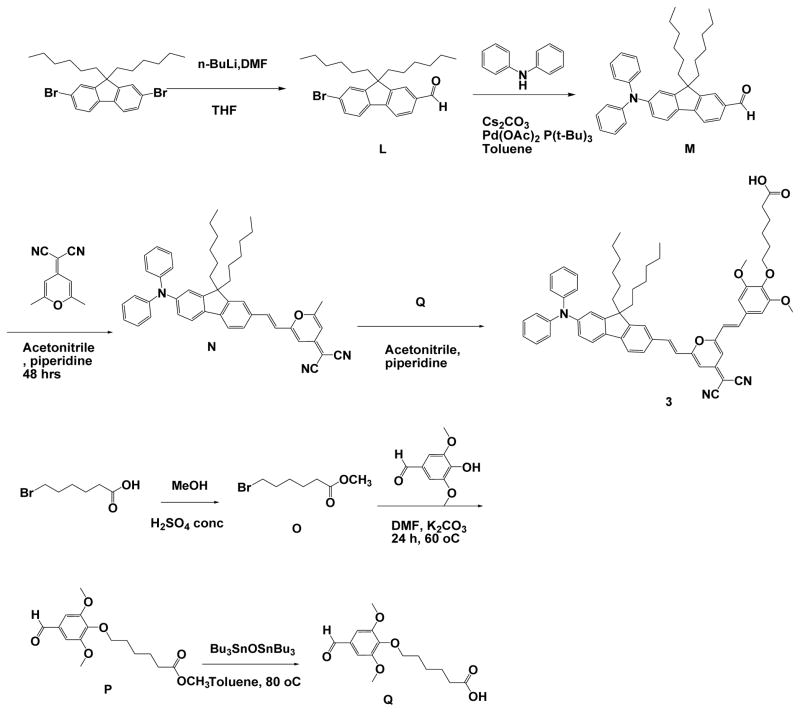

The absorption spectrum of 1 (Figure 1, A) exhibited a maximum absorbance at ~ 460 nm, with only nominal variation as a function of solvent polarity. This behavior also extended to the shorter wavelength band (~ 315 nm), though the ratio between this and the main peak decreased somewhat with increasing solvent polarity. Excitation in the main absorption band resulted in a fluorescence signal that displayed a distinct solvatochromic pattern (Figure 1, A): λmax underwent a bathochromic shift, the peak broadened, and the quantum yield of the fluorescence decreased with increasing polarity (Table 1). These results are comparable to a hydrophobic analogue previously reported;20 the decreased fluorescence quantum yield is a likely result of the increased flexibility rotational propensity of the pendant chains in the 9-position of the fluorene moiety.

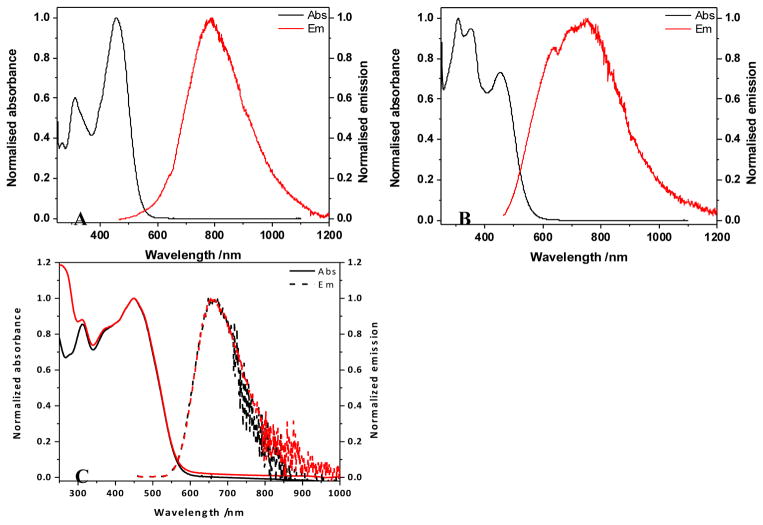

Figure 1.

(A) Absorption (solid lines) and emission (dashed lines) spectra in toluene (black), DCM (red), and DMSO (blue), excitation anisotropy in silicone oil (dark green), and two-photon absorption spectrum in DCM (dark red circles) for 1; (B) absorption (solid lines) and emission (dashed lines) spectra in DMSO (black), and water (red), excitation anisotropy in DMSO (dark green), two-photon absorption spectrum in DMSO (dark red triangles) for 2; (C) absorption (solid lines) an emission (dashed lines) spectra in toluene (black), and DCM (red), excitation anisotropy in silicone oil (dark green), and two-photon absorption spectrum in DCM (dark blue triangles) for 3.

Table 1.

Photophysical parameters for 1 and 2, their RGD conjugates, (1a and 2a), and 3 in organic solvents and organic nanoparticles (3a and 3b)

| Compound | Solvent | a/nm | a/nm | Δλ b/nm | Φf c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toluene | 461 | 585 | 124 | 0.35 |

| DCM | 458 | 704 | 246 | 0.38 | |

| DMSO | 454 | 789 | 335 | 0.01 | |

| 1a | DMSO | 455 | 789 | 334 | 0.02 |

| 2 | DMSO | 308, 360, 463 | 652 | 199 | 0.02 |

| H2O | 308, 361, 469 | 720 | 251 | 0.01 | |

| 2a | DMSO | 310, 353, 454 | 754 | 300 | 0.02 |

| 3 | Toluene | 449 | 591 | 142 | 0.31 |

| DCM | 445 | 767 | 322 | 0.03 | |

| 3a | H2O | 449 | 648 | 199 | 0.03 |

| 3b | H2O | 450 | 662 | 212 | 0.05 |

Absorption and emission maxima ±1 nm;

Stokes shift ±2 nm;

fluorescence quantum yields ±10%

In the case of 2, the absorption spectrum extended to a longer wavelength, as expected for the conjugated system; however this is a tail, with the major peak at short wavelength (~ 310 nm; Figure 1, B). This implies that there is a break in the conjugation of the system, in comparison to a previous reported hydrophobic form and its thiopyran analogue that exhibited absorption maxima at longer wavelength (470–500 nm).15, 21 Despite this, the absorption spectra recorded in DMSO and water showed little differences, though their weak emissions indicate a degree of solvatochromism, consistent with an increase in solvent polarity (Table 1).

As an asymmetrical molecule, the spectra of 3 bear a resemblance to those of 1, implying that the alkoxystyryl moiety has little impact on the electronic properties of the molecule (Figure 1, C). The long alkyl chains of the fluorenyl moiety and on the para position of the alkoxyl styryl vinylidene appears to exude a detrimental effect on the fluorescence quantum yield, particularly in DCM, speculatively due to their flexible natures (Table 1).

The excitation anisotropy of 1 achieved a plateau in the region of the main absorption band, defining this absorption as a single transition of the ground to excited state (Figure 1, A). This is in contrast to that of 2, where there is no plateau present; inferring that excitation at the long wavelength shoulder or the short wavelength peak induces more than one electronic transition (Figure 1, B). Similarly, the trace determined for 3 has a small plateau above 500 nm overlooking valleys at ~420 nm and ~310 nm, and a lesser peak at ~350 nm.

Notwithstanding the differences in the linear absorption spectra and excitation anisotropy, the two-photon absorption spectra for these compounds exhibit reasonable similarities: a peak at 1000 nm of 150–200 GM rising from a region (700–900 nm) undulating around 100 GM. The shorter wavelength absorption of 1 and 3 allowed measurements at shorter wavelengths (<700 nm), where the measured cross sections rise to >500 GM, though a peak could not be resolved due to encroaching linear absorption.

The conjugation of 1 and 2 to cRGDfK (resulting in 1a and 2a, respectively), had little effect on the linear photophysical properties of the chromophores (Figure 2, A and B), though both retain the low fluorescence quantum yields exhibited in the DMSO solutions of the unconjugated chromophore. Due to this similarity, and the small quantity generated, non-linear measurements were not performed on the conjugates, assuming properties are comparable to the nanoconjugated precursors (1 and 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Absorption and emission spectra for 1a in DMSO; (B) Absorption and emission spectra for 2a in DMSO; (C) Absorption (solid lines) and emission (dashed lines) spectra for 3 in organic nanoparticles without, 3a (black), and with, 3b (red) added lecithin.

The formation of 3 as organic nanoparticles had little effect on the value of , as it remained at ~450 nm (Figure 2, C). The rise observed at short wavelength in the spectrum of 3b is attributable to the presence of the lecithin in solution. The nominal difference in the emission profiles is due mainly to the noise, given the region and intensity of the emission.

The fluorene and pyran rings in structures are able to rotate upon the axes of the olefinic double bonds, resulting in conformational flexibility. This flexibility may cause a decrease in fluorescence intensity (quantum yield). Restriction of intramolecular rotations may stiffen the molecular conformation, leading to aggregation induced emission activity. This effect can be larger with two olefinic double bonds substituted at both sides,8b, 22 affording an advantage when applying hydrophobic structures in aqueous solution. However, for hydrophilic structures 1 and 2, the flexibility becomes unfavorable. Due to steric hinderance of the long PEG chain at both fluorene substitutents, it would be difficult for 2 to maintain a planar conformation. As a result, 2 possessed a comparably lower 2PA cross section than 1.

Nanoparticle characterization

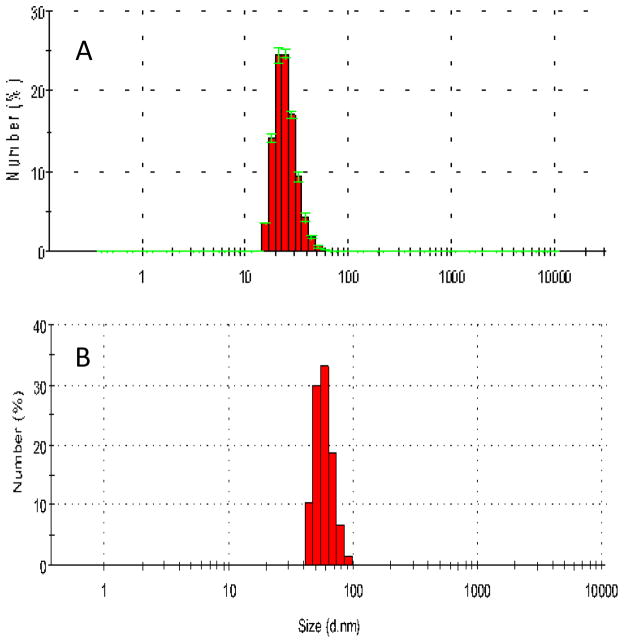

Nanoparticle sizes were analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The results show that the average particles size was ca 30 nm and 50 nm for 3a and 3b, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Size distribution of organic nanoparticles 3a (A) and 3b (B) determined by DLS.

Probe uptake by cells

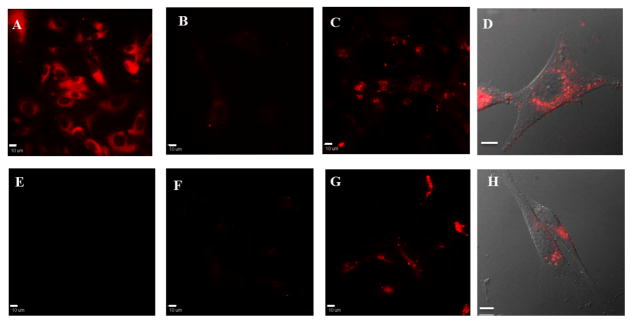

Both 1a and 2a gave good cell viability (> 80% after 24 h incubation) below 12.5 μM (ESI, Figure S1). Multiple negative controls were performed to demonstrate integrin-targeting specificity. MCF-7 cells, which were reported as αvβ3 negative,16 exhibited no noticeable fluorescence after incubation with either RGD-conjugated dye (ESI, Figure S2). In contrast, U87MG cells displayed bright fluorescence after 1 h incubation with 1a and 2a (Figure 4, C and G). The fluorescence mainly appeared in a granular pattern associated with vesicles around perinuclear area (Figure 4, D and H), indicating uptake of the probes. U87MG cells incubated with free RGD before incubation with the RGD-conjugated structures exhibited low fluorescence; indicating blocking (saturation) of αvβ3 binding sites by free RGD attenuated the uptake of the RGD conjugates (Figure 4, B and F). The respective dyes (1 and 2) without RGD conjugation were also employed to confirm the role of RGD. Although U87MG cells displayed bright fluorescence after incubation with 1, the fluorescence signal exhibited a non-specific distribution (Figure 4, A). On the other hand, when unconjugated 2 was applied, no obvious signal was detected from cells (Figure 4, E), demonstrating the significance of RGD for specific uptake of the probe.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence (A–C, E–G) and DIC overlay (D, H) images of U87MG cells after 1 h incubation with 1 (A), 1a (B–D), 2 (E) or 2a (F–H). B and F were pre-incubated with free RGD peptide. Scale bars are 10 μm.

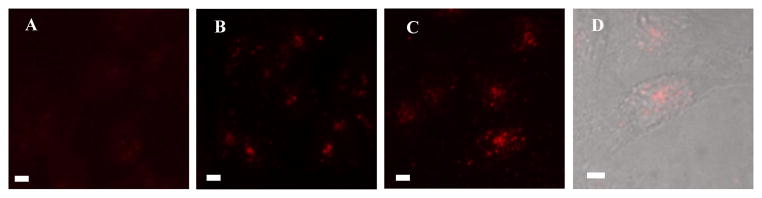

Organic nanoparticles (3a and 3b) showed good internalization into cells (Figure 5). With the presence of lecithin, more 3b nanoparticles were observed inside cytoplasm, indicating the synergistic function of lecithin for cell uptake.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence (A–C) and DIC overlay (D) images of HCT116 cells after 1 h incubation with medium (A), 3a (B), or 3b (C, D). Scale bars are 10 μm.

Although the organic nanoparticles 3a and 3b exhibited better fluorescence quantum yields than the RGD conjugated structures 1a and 2a, their corresponding cell images were not as bright as the latter’s. The cell imaging results demonstrated that, despite the low fluorescence quantum yield, RGD-conjugated hydrophilic pyranyl structures perform quite suitably as bioimaging dyes.

Integrin Targeted Tumor Imaging

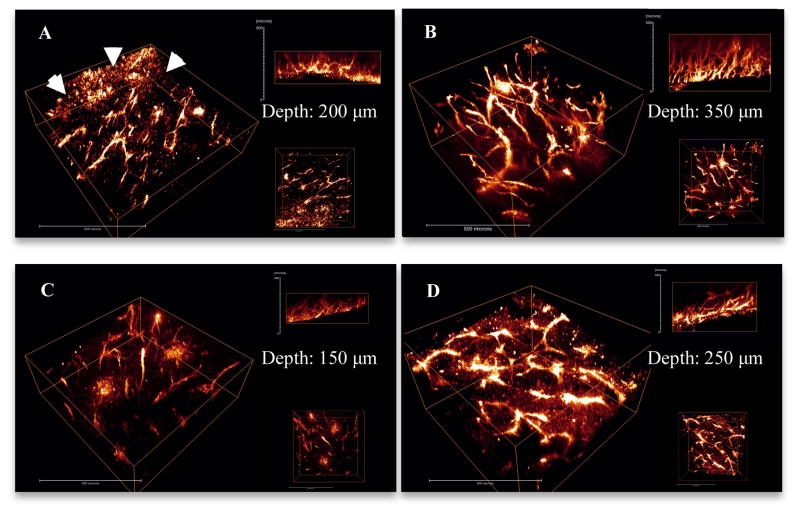

Tumor tissues harvested from mice injected with unconjugated 1 exhibited a certain degree of fluorescence (Figure 6, A). However, when compared with 1a (Figure 6, B), the fluorescence intensity of 1 was lower. The selectivity of 1 was also poor. Many cells other than vessel endothelium lit up in the background (shown with arrows, Figure 6, A). On the other hand, fluorescence from 1a was well distributed selectively on tumor vessels. This is consistent with the cell imaging comparison between 1 and 1a, indicating more specific endocytosis and targeting with the RGD-conjugated dye. In addition penetration of 1a (350 μm) appeared significantly deeper than 1 (200 μm).

Figure 6.

3D reconstruction images show the vasculature in LLC tumor implants that were extracted from mice injected with 1 (A), 1a (B), 2 (C) and 2a (D). Arrows in A indicate non-specific uptake of 1. Each image shows 3D view (left), x-z view (right top) and x-y view (right bottom). Scale bars are 50 μm.

Tumor tissues collected from mice injected with unconjugated 2 exhibited very low fluorescence (Figure 6, C), while for tumors from mice injected with 2a, the fluorescence intensity was much higher (Figure 6, D), indicating unconjugated 2 could not be efficiently targeted to the endothelium of tumor vessels, consistent with results of cell imaging with 2. In addition, the fluorescence penetration of 2a was much deeper than unconjugated 2. It should be noted that angles on the surface make the images look deeper than they actually are. Therefore, samples with similar surface angles were selected for comparison. The actual depths of observed fluorescence were 150 μm for 2 and 250 μm for 2a, further confirming the deeper tissue imaging facilitated by the RGD conjugate.

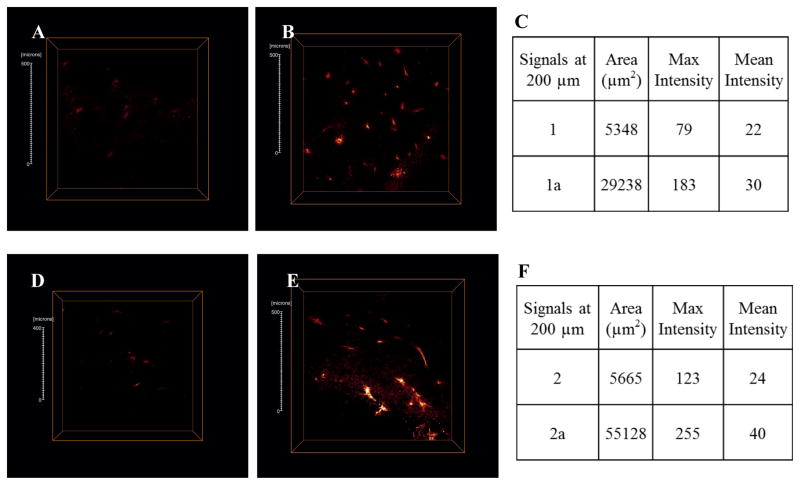

Additional evidence is shown in the cross-section images (Figure 7). Little fluorescence can be observed for both 1 and 2 at 200 μm depth. However, 1a and 2a exhibit bright, well defined fluorescence. Quantitative analysis of the cross-sections gave distinguished differences in both signal area and intensity (Figures 7 C and 7 F). Bright fluorescence in both cell and tissue images demonstrated adequate emission intensity of both dyes in one-photon and two-photon fluorescence microscopy.

Figure 7.

Optical cross-section fluorescence at 200 μm depth for 1 (A), 1a (B), 2 (D) and 2a (E) were analyzed. Scale bars are 50 μm.

Observation of living tissues is hard to achieve with conventional (confocal) fluorescence microscopy because short excitation wavelengths often employed undergo scattering and absorption in tissues, increasing background noise. Additionally, the excessive excitation energy outside the focal plane may bleach surrounding chromophores or cause photodamage 2b to tissue. 2PFM technologies make in vivo tissue imaging possible by using longer wavelengths and extremely localized focal plane. Although applying longer wavelength can result in lower resolution (r=λ/2NA), however, the slight resolution decrease didn’t affect the observation of clear tumor vasculature. As a result, 2PFM imaging technologies are superior for deep vasculature imaging relative to cell organelle or receptor observation. Overall, the results realized here show fluorescence collected at a depth of 350 μm by 2PFM (Figure 7B). The images of the tumor vasculature structures were well defined even at this depth into solid tumor tissue. RGD conjugated structures displayed better imaging efficiency than unconjugated corresponding probes.

Conclusions

Fluorene-substituted pyran derivatives PF 1 and PF 2 were designed as hydrophilic structures, showing good photophysical properties in DMSO. After conjugation with the αvβ3 integrin targeting cyclic RGDfK peptide, both structures exhibited significant vasculature targeting. Penetration of fluorescence emission was observed as deep as 350 μm, with good resolution of vasculature structures. Our results suggest the utility of the improved tumor vascular targeting pyranylidene probes for in vivo imaging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge support from the National Science Foundation (CBET-1517273, CBET-1403535, and CHE-0832622), the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (PGA-P210877), and National Cancer Institute/NIH (2R01CA125255).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [synthetic details, cell viability assay, fluorescent images of control groups, NMR and mass spectra]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Fukumura D, Duda DG, Munn LL, Jain RK. Microcirculation. 2010;17(3):206–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26(4):357–370. doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tozer GM, Ameer-Beg SM, Baker J, Barber PR, Hill SA, Hodgkiss RJ, Locke R, Prise VE, Wilson I, Vojnovic B. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57(1):135–152. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Beerling E, Ritsma L, Vrisekoop N, Derksen PWB, van Rheenen J. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(3):299–310. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishida N, Yano H, Nishida T, Kamura T, Kojiro M. Vasc Health Risk Manage. 2006;2(3):213–9. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avraamides CJ, Garmy-Susini B, Varner JA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(8):604–617. doi: 10.1038/nrc2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks PC, Clark RA, Cheresh DA. Science. 1994;264(5158):569–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Friedlander M, Brooks PC, Shaffer RW, Kincaid CM, Varner JA, Cheresh DA. Science. 1995;270(5241):1500–2. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfaff M, Tangemann K, Muller B, Gurrath M, Muller G, Kessler H, Timpl R, Engel J. J Bio Chem. 1994;269(32):20233–20238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirano Y, Kando Y, Hayashi T, Goto K, Nakajima A. J Biomed Mater Res. 1991;25(12):1523–1534. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820251209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dechantsreiter MA, Planker E, Matha B, Lohof E, Holzemann G, Jonczyk A, Goodman SL, Kessler H. J Med Chem. 1999;42(16):3033–3040. doi: 10.1021/jm970832g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tanabe K, Zhang Z, Ito T, Hattaa H, Nishimoto S. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2007;5:3745–3757. doi: 10.1039/b711244k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cai W, Niu G, Chen X. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2008;14(28):2943–2973. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pecher J, Huber J, Winterhalder M, Zumbusch A, Mecking S. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(10):2776–2780. doi: 10.1021/bm100854a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang XH, Morales AR, Urakami T, Zhang LF, Bondar MV, Komatsu M, Belfield KD. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22(7):1438–1450. doi: 10.1021/bc2002506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Qin W, Ding D, Liu JZ, Yuan WZ, Hu Y, Liu B, Tang BZ. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22(4):771–779. [Google Scholar]; Chen YC, Lo CL, Hsiue GH. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2014;102(6):2024–2038. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim ST, Chun MH, Lee KW, Shin DM. Opt Mater. 2003;21(1–3):217–220. [Google Scholar]; Andreu R, Galan E, Garin J, Herrero V, Lacarra E, Orduna J, Alicante R, Villacampa B. J Org Chem. 2010;75(5):1684–1692. doi: 10.1021/jo902670z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geng JL, Li K, Ding D, Zhang XH, Qin W, Liu JZ, Tang BZ, Liu B. Small. 2012;8(23):3655–3663. doi: 10.1002/smll.201200814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DY, Kim JN, Kim HJ. Spectrochim Acta, Part A. 2014;122:304–8. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amro K, Daniel J, Clermont G, Bsaibess T, Pucheault M, Genin E, Vaultier M, Blanchard-Desce M. Tetrahedron. 2014;70(10):1903–1909. [Google Scholar]; Zhang XQ, Zhang XY, Yang B, Zhang YL, Wei Y. Tetrahedron. 2014;70(22):3553–3559. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Morales AR, Yue X, Luchita G, Przhonska OV, Kachkovsky OD. Chemphyschem. 2012;13(15):3481–3491. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201200405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Morales AR, Frazer A, Mikhailov IA, Przhonska OV. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117(23):11941–11952. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deryugina EI, Bourdon MA, Jungwirth K, Smith JW, Strongin AY. Int J Cancer. 2000;86(1):15–23. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000401)86:1<15::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savariar EN, Aathimanikandan SV, Thayumanavan S. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(50):16224–16230. doi: 10.1021/ja065213o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rathnayake HR, Cirpan A, Delen Z, Lahti PM, Karasz FE. Adv Funct Mater. 2007;17(1):115–122. [Google Scholar]; Salomon CJ, Mata EG, Mascaretti OA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32(34):4239–4242. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang CL, Wu MT, Dai DC, Wen YS, Wang JK, Chen CT. Adv Funct Mater. 2005;15(2):231–238. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morales AR, Frazer A, Woodward AW, Ahn-White HY, Fonari A, Tongwa P, Timofeeva T, Belfield KD. J Org Chem. 2013;78(3):1014–1025. doi: 10.1021/jo302423p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belfield KD, Bondar MV, Morales AR, Padilha LA, Przhonska OV, Wang XH. Chemphyschem. 2011;12(15):2755–2762. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong H, Hong YN, Dong YQ, Ren Y, Haussler M, Lam JWY, Wong KS, Tang BZ. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(8):2000–2007. doi: 10.1021/jp067374k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.