Abstract

Objectives. We determined whether and how Minnesotans who were uninsured in 2013 gained health insurance coverage in 2014, 1 year after the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded Medicaid coverage and enrollment.

Methods. Insurance status and enrollment experiences came from the Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MH-HITS), a follow-up telephone survey of children and adults in Minnesota who had no health insurance in the fall of 2013.

Results. ACA had a tempered success in Minnesota. Outreach and enrollment efforts were effective; one half of those previously uninsured gained coverage, although many reported difficulty signing up (nearly 62%). Of the previously uninsured who gained coverage, 44% obtained their coverage through MNsure, Minnesota’s insurance marketplace. Most of those who remained uninsured heard of MNsure and went to the Web site. Many still struggled with the enrollment process or reported being deterred by the cost of coverage.

Conclusions. Targeting outreach, simplifying the enrollment process, focusing on affordability, and continuing funding for in-person assistance will be important in the future.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA; Pub L No. 111–148) significantly increased the availability of health insurance coverage for millions of Americans through expansion of the Medicaid program and the offer of insurance options and subsidies through health insurance marketplaces.1 The ACA also devoted significant resources to outreach and enrollment to ensure that increases in availability and access led to gains in coverage.

There is clear evidence that the ACA has led to significant health insurance coverage gains. Between September 2013 (before the initial ACA open enrollment) and December 2014, more than 10.75 million additional individuals enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program across the United States, representing an 18.6% increase in the average monthly enrollment.2 Enrollment gains in qualified health plans offered through marketplaces were also significant. As of January 2015, 9.5 million people were enrolled in health plans purchased through marketplaces.3 Data from several national cross-sectional surveys confirmed these enrollment gains and indicated significant reductions in the number of uninsured.4–6 We followed uninsured Minnesotans over time to examine the impact of the ACA.

History has shown that availability of health insurance options does not necessarily translate into enrollment. Specifically, participation in Medicaid among eligible adults is incomplete and varies across the states, ranging from less than 44% in Oklahoma to 88% in the District of Columbia, with a national average of 62%.7 Key barriers to Medicaid enrollment include a lack of knowledge among potentially eligible individuals about the program (e.g., eligibility and renewal requirements, and how to sign up) and inadequate enrollment support for individuals (e.g., language and literacy barriers).8 For this reason, the architects of the ACA included a variety of provisions intended to encourage participation in health insurance coverage, including outreach and enrollment support, as well as an individual mandate to obtain coverage.

The development of health insurance marketplaces was central to outreach and enrollment efforts; these marketplaces were intended to be a one-stop shop for individuals looking to find coverage and an organizer for outreach efforts. States could opt to implement a state-based marketplace or rely fully or partially on the federally facilitated marketplace. Marketplaces were tasked with implementing a single, streamlined eligibility process; consumer assistance activities, including Web site development, call center, and assister programs; and supporting multiple pathways for gaining coverage (e.g., online, mail, telephone, and in person). Significant federal resources were available to both support Marketplace development and fund enrollment efforts by those marketplaces.9–11

As a state-based marketplace, MNsure has been responsible for outreach and enrollment efforts, and benefited from the available federal funding. As of fall 2014, Minnesota received a total of $155 million in federal grants for state-based Marketplace planning and implementation,9 including nearly $6 million to support public outreach, navigators, and other in-person assister programs.12,13 Specifically, MNsure developed a Consumer Assistance Program to support “no-wrong-door” application assistance through the training and funding of certified application counselors, navigators, and outreach and enrollment grantees who were charged with engaging communities, educating individuals about their coverage options, and supporting them through the enrollment process. Specific activities conducted by consumer assistance providers included regular weekly navigator enrollment and assistance hours at community centers and places of worship, referrals with small business groups and health care providers, locally focused print and social media campaigns, and town hall forums.14

Our purpose was to determine whether and how individuals most likely to be eligible for new ACA health insurance coverage options gained insurance in 2014, the first year of expanded Medicaid and nongroup enrollment under MNsure. Specifically, we followed a group of children and adults who were uninsured in the fall of 2013 and asked a year later about their insurance coverage, main reasons for lack of coverage, awareness of MNsure, coverage-related information-seeking, use of MNsure enrollment resources, overall enrollment experiences, access to care, and perceived financial protection related to health care. We add to the limited data that examine the enrollment experiences of the uninsured during the first full year of ACA implementation.15,16

METHODS

The Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MN-HITS) is a longitudinal study of individuals who lacked health insurance or who had health insurance coverage through the nongroup market in Minnesota in the fall of 2013.17

We gathered data for the study’s sample from the 2013 Minnesota Health Access Survey (MNHA), the state’s biennial dual-frame random digit dial telephone household survey. The MNHA is designed to assess health insurance coverage and health care access, use, and affordability for a representative sample of the general population in Minnesota. Questions about health insurance coverage are asked of all individuals in a sampled household, whereas detailed health care access and use questions are asked only about 1 randomly selected adult or child within the household (“target”). The sampling frame for MN-HITS was based on a specific group of 2013 MNHA targeted individuals. Specifically, it included targets who were nonelderly (aged 0–63 years) and who reported being uninsured or having nongroup coverage (including coverage through the Minnesota’s high-risk pool). Because the age determination was based on reported age in the fall of 2013, the final sample included children and nonelderly adults aged 0 to 64 years in 2014 (interviews for children younger than 18 years were completed by an adult in the household). MN-HITS was approved by institutional review boards at both the University of Minnesota and Minnesota Department of Health.

Our final sampling frame included 762 uninsured individuals and 748 nongroup insured individuals, for a total of 1510 individuals. We recontacted these individuals in the fall of 2014 using a computer-assisted telephone interview survey. We conducted the interviews in English and Spanish. Ultimately, 218 of the uninsured sample members and 275 of the nongroup insured sample members completed the 2014 recontact survey (n = 493). The response rate (the American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate 3)18 for the 2013 MNHA was 48%, and the response rate for the recontact survey was 42.5%. The response rates are on the moderate to high end of the distribution for state health insurance surveys19 and comparable to a recent statewide20 and recontact survey conducted in Oregon (Rebekah Gould, personal communication, March 2015).

Our results focused exclusively on the 218 individuals who reported being uninsured in the 2013 MNHA survey and completed the recontact survey, herein referred to as the “previously uninsured.” Bivariate analyses that compared the 218 uninsured individuals who completed the survey and the 544 uninsured nonrespondents indicated very few differences between the 2 groups in terms of demographic characteristics, health status, past health care access and use, and familiarity with ACA provisions (see data available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The only exceptions were age (fewer recontact respondents than nonrespondents were younger adults and more were aged 55–64 years) and hospitalization use in the past 12 months (fewer respondents had been hospitalized than nonrespondents).

Measures

In addition to the core MNHA questions on health insurance coverage and access to care, the 2014 recontact survey included a number of metrics directly related to ACA provisions implemented in 2014: purchase of or enrollment in coverage through MNsure, whether the target individual had looked for insurance in 2014, why the target individual had purchased coverage, and use of MNsure enrollment resources. We drew or adapted these ACA-related questionnaire items from several national enrollment or health reform surveys to have benchmark data available and build upon research that assessed the validity and reliability of these measures. We adapted items from the Current Population Survey, the CMS Federal Marketplace Survey, the Perry Undem/Enroll America Post-ACA Enrollment Survey, the Commonwealth Fund ACA Tracking Survey, the Urban Institute’s Health Reform Monitoring Survey, and the Kaiser Survey of the ACA and Low-income Americans.21,22

We assessed health insurance coverage in both 2013 and 2014 by asking about a comprehensive list of possible types of coverage. Although respondents were able to report multiple coverage sources, each target was coded to a single source using a hierarchy in the following order: public (Medicare, Medicaid, Minnesota Care, and military), group (employer-sponsored insurance, COBRA), nongroup (direct purchase), and uninsured. In line with the US Census Bureau,23 we coded targets who reported only Indian Health Services (IHS) as uninsured. The 2014 survey asked whether the target purchased or enrolled in coverage through MNsure, paid a premium, and received a premium subsidy.24 The survey also inquired about the main reasons for selecting a plan or for remaining uninsured using an open-ended response format.

The 2014 survey also asked whether targets had tried looking for insurance coverage since October 2013, what resources targets had used to look for or enroll in coverage (including the MNsure Web site, the MNsure call center, and in-person help), whether targets had access to resources needed for signing up for coverage (i.e., access to bank accounts, credit cards, and the Internet), and what their general experience was like. We assessed targets’ experiences looking for or enrolling in coverage by asking if targets felt they had received the information they needed and how easy or difficult it was to sign up for coverage. Perceived financial protection was assessed by an item that asked whether respondents felt well protected in terms of health care, worried that their needed health care would not be paid for, or worried that they might have at least some health care needs that would be difficult to afford. Finally, the survey included a standard set of demographic characteristic questions.

Analysis

We weighted data using the 2013 MNHA survey weight and an adjustment for nonresponse in the 2014 recontact survey. We generated the initial MNHA 2013 base weights to account for each respondent’s probability of selection (which varied by geographic strata, the number of people in the household, the type of phone used [landline or cell phone], and the number of telephones in the household). Using the 2012 American Community Survey, we then poststratified the 2013 MNHA weights to approximate the distribution of the sample to that of the state’s population based on age, race/ethnicity, education, age by education, country of origin (United States vs foreign born), home ownership, geography, and household size. We used a raking algorithm to optimize the iteration process of poststratification (i.e., lower SEs within the minimum number of iterations necessary).

Although we observed few differences between the 2014 recontact survey respondents and nonrespondents, we adjusted for potential response bias in the recontact survey using propensity score weights, which are widely used when adjusting for nonresponse bias in longitudinal studies.25,26 We estimated the propensity score for the previously uninsured and nongroup insured samples separately. The final weights were created by multiplying the 2013 weights by the inverse of the 2014 predicted propensity score. To evaluate the weights, we examined a set of demographic characteristics (e.g., the distribution of gender, age, race, country of origin, marital status, education, employment status, health insurance unit income, home ownership, and urbanicity) using the original weighted 2013 sample (n = 1510) and the reduced 2014 sample (n = 493) with these new weights and found no statistical difference in any of these variables.

We conducted all analyses with Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) to account for the complex survey design.27 We used the t-test to test for differences in means. Consistent with US Census Bureau and National Center for Health Statistics practices,28 we limited the presentation of results to those with a denominator of at least 50 cases, and we labeled results with a relative SE (SE divided by estimate) of more than 0.3.

RESULTS

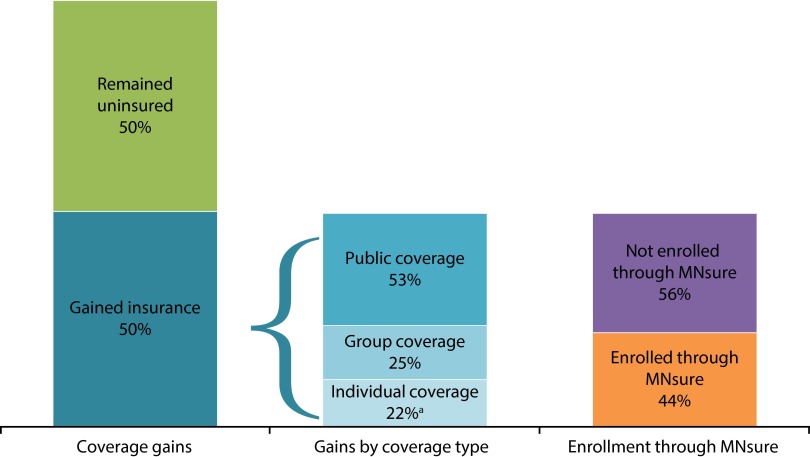

Half of the previously uninsured Minnesotans in 2013 reported gaining coverage by the time of the 2014 survey. The majority of those with new coverage gained public insurance (53%), one quarter gained group coverage, and 22% gained nongroup coverage (Figure 1). Of the previously uninsured who gained coverage, 44% reported that they obtained their coverage through Minnesota’s Marketplace, MNsure (17% gained nongroup and 27% gained public insurance through MNsure).

FIGURE 1—

Gains in and pathways to coverage for the previously uninsured: Minnesota, 2013–2014.

Source. Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MN-HITS).

aRelative SE > 0.3—use caution.

There were only 2 demographic characteristic differences between the previously uninsured who gained coverage and those who remained uninsured (Table 1). Those who gained coverage were more likely to be children (aged 0–17 years), and they (or their parents) were more likely to have higher education (some college to postgraduate degree).

TABLE 1—

2013 Demographics of Previously Uninsured by 2014 Coverage Status: Minnesota, 2013–2014

| Variable | Gained Coverage (n = 120), % (SE) | Remained Uninsured (n = 98), % (SE) |

| Uninsurance duration | ||

| Short-term uninsured (≤ 12 mo in 2013) | 38.9 (7.2) | 20.9 (6.3) |

| Long-term uninsured (> 12 mo in 2013) | 61.1 (7.2) | 79.1 (6.3) |

| Age, y | ||

| 0–17 | 38.1 (8.4) | 12.7 a,** (4.8) |

| 18–34 | 26.0 (6.2) | 40.1 (8.7) |

| 35–64 | 35.9 (6.7) | 47.2 (8.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-White | 65.6 (8.4) | 53.6 (8.5) |

| White | 34.4 (8.4) | 46.4 (8.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 56.9 (7.4) | 66.6 (7.7) |

| Female | 43.1 (7.4) | 33.4 (7.7) |

| Marital status (only age ≥ 18 y, missing for some) | ||

| Not married | 66.8 (7.1) | 74.1 (6.9) |

| Married | 33.2 (7.1) | 25.9 (6.9) |

| Income/federal poverty guidelines,b % | ||

| 0–< 138 | 38.4 (7.7) | 47.3 (8.5) |

| 138–400 | 55.0 (7.7) | 47.8 (8.4) |

| > 400 | 6.6a (2.4) | 5.0a (2.6) |

| Area of residence | ||

| Metropolitan | 48.7 (7.8) | 55.4 (8.5) |

| Greater Minnesota/rural | 51.3 (7.8) | 44.6 (8.5) |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed | 20.1 (5.9) | 27.3 (7.4) |

| Employed | 80.0 (5.9) | 72.7 (7.4) |

| Education | ||

| ≤ high school graduate | 40.2 (8.3) | 64.2* (7.2) |

| College or postgraduate | 59.9 (8.3) | 35.8* (7.2) |

| Self-reported health status | ||

| Fair/poor health | 19.5a (7.2) | 14.9a (6.4) |

| Excellent/very good/good health | 80.5 (7.2) | 85.1 (6.4) |

Note. Unweighted number is presented. Demographic characteristic data were collected in 2013 unless otherwise noted.

Source. Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MN-HITS).

Relative SE > 0.3—use caution.

Federal poverty guidelines according to the US Department of Health and Human Services.1

*P < .05; **P < .01.

Cost seemed to drive coverage decisions among the previously uninsured who remained uninsured; 45% cited affordability (plans were too expensive or they could not afford coverage) as the primary reason for not having health insurance in the fall of 2014 (data not shown in Table 1). Among those who gained coverage in 2014, the most common reasons cited for obtaining insurance included ACA-related reasons (e.g., it is required, did not want to pay fine, and the subsidies or tax credits available), the desire or need to access medical care, and a change in life circumstances (e.g., job gains and losses) that led to a gain in eligibility to private or public insurance (data not shown).

Use of Marketplace Enrollment Resources

Regardless of their 2014 health insurance coverage status, many of the previously uninsured (76%) looked for health insurance coverage sometime between the fall of 2013 and the fall of 2014 (data not shown). This included people who said they looked for coverage in general or reported going to the Marketplace or MNsure Web site, reaching the call center, or getting in-person assistance. Of the previously uninsured who looked for coverage, more than three quarters (79%) reported they had heard about MNsure (data not shown).

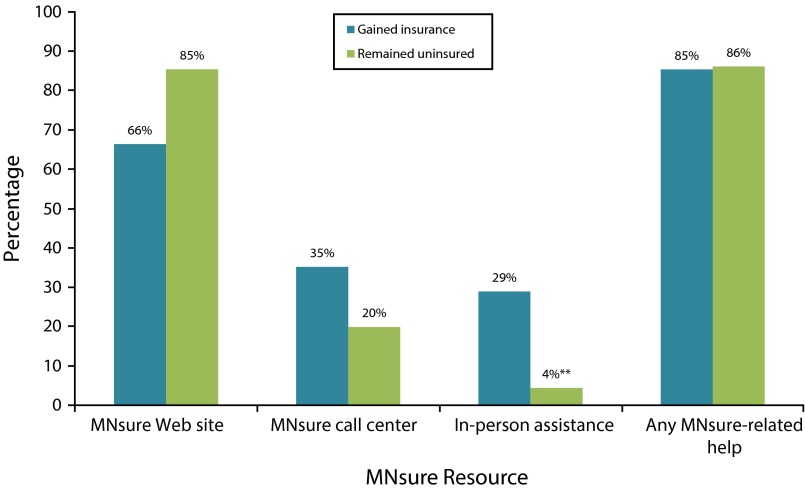

As shown in Figure 2, those who gained coverage and those who remained uninsured were equally likely to have used at least 1 of the available MNsure resources (approximately 85%). However, those who gained coverage were more than 7 times more likely to seek help from an in-person assister (29% vs 4%).

FIGURE 2—

Use of MNsure resources among previously uninsured by 2014 coverage status: Minnesota, 2013–2014.

Note. Analysis is restricted to the previously uninsured who reported looking for coverage and/or reported using a MNsure enrollment resource. Respondents can report using multiple resources; therefore, bars do not sum to 100%.

Source. Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MN-HITS).

**P < .01.

Experiences Signing Up for Coverage

Table 2 shows that of the previously uninsured who looked for health insurance coverage sometime between the fall of 2013 and the fall of 2014 (76%), more of those who gained coverage (90%) reported getting the information they needed to sign up for health insurance compared with those who remained uninsured (32%). However, almost two thirds of those who looked for and gained coverage (62%) reported it was somewhat or very difficult to sign up for health insurance. An even greater share (84%) of those who looked for insurance yet remained uninsured reported difficulty signing up for coverage.

TABLE 2—

Enrollment Experiences of Previously Uninsured by 2014 Coverage Status: Minnesota, 2013–2014

| Variable | Gained Coverage (n = 98), % (SE) | Remained Uninsured (n = 71), (SE) |

| Got information needed to sign up | ||

| Yes | 89.5 (4.4) | 31.6a,*** (10.3) |

| No | 10.5a (4.4) | 68.4*** (10.3) |

| Ease or difficulty signing up for health insurance | ||

| Very, somewhat easy | 38.5 (7.3) | 16.0a,* (8.8) |

| Very, somewhat difficult | 61.5 (7.3) | 84.0* (8.8) |

| Have resources that impact ease of gaining or keeping health insurance | ||

| Credit card | 67.2 (7.5) | 40.0* (9.4) |

| Savings or checking account | 94.3 (3.1) | 58.6** (10.7) |

| Internet at home | 80.5 (5.7) | 72.6 (10.0) |

| Internet on phone | 66.3 (7.1) | 71.0 (10.1) |

| Internet at any place | 90.0 (4.1) | 81.2 (9.5) |

| Perception of financial protection | ||

| I feel well-protected when it comes to my health care needs | 53.0 (8.0) | 15.8** (5.6) |

| I worry that I might have health care needs that will be difficult to pay for | 42.2 (8.0) | 43.6 (8.9) |

| I worry that my health care needs won’t be paid for | 4.8 (1.9) | 40.6*** (8.6) |

Note. Unweighted number is presented. Analysis is restricted to the previously uninsured who reported looking for coverage and/or reported using a MNsure enrollment resource.

Source. Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MN-HITS).

Relative SE > 0.3—use caution.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Finally, those who gained insurance in 2014 were more likely than those who remained uninsured to have the financial resources, such as credit cards or savings and checking accounts, necessary to sign up for insurance and make monthly premium payments.

Perceptions of Financial Protection

Table 2 also shows that there were significant differences in perceptions of financial protection between those who gained health insurance and those who remained uninsured. Of those who looked and gained insurance, 53% reported feeling well-protected when it came to their health care needs compared with 16% of those who looked for coverage yet remained uninsured. By contrast, those who looked and remained uninsured were more likely than those who gained insurance to report that they worried that their health care needs would not be paid for (approximately 41% vs 5%).

DISCUSSION

Our longitudinal study provided an early and unique view of the experiences and coverage decisions that a known group of uninsured individuals made during the initial ACA open enrollment period. Consistent with findings using administrative counts,29 half of the previously uninsured in Minnesota gained coverage in 2014. Of these, more than half (53%) who gained coverage enrolled in a public program. The rest of the previously uninsured who gained coverage were split between nongroup (22%) and group coverage (25%), which reflected job changes that led some to gain private insurance. Because Minnesota was an early adopter of the Medicaid expansion,30 our results from 2013 to 2014 might underestimate the coverage impact of the ACA’s 2014 provisions on the uninsured, because an initial portion of the overall ACA effect might have taken place before the 2013 MNHA data were collected.

Our results suggested that MNsure outreach and enrollment assistance played an important role in increased coverage. Specifically, 44% of those who gained insurance reported enrolling through MNsure. Almost 80% of the previously uninsured had heard of MNsure, and 76% looked into obtaining coverage, which speaks to the success of outreach efforts throughout the state. Consistent with national data,15 the majority of the previously uninsured (85%) used at least 1 MNsure enrollment resource, especially the MNsure Web site. However, individuals who gained coverage were almost 7 times more likely to get in-person assistance during the enrollment process. These results illustrate the importance of the Web site in reaching a broad audience, but the results also suggest the importance of in-person assistance in helping people go beyond looking for health insurance to enrolling in coverage.15

Despite pervasive use of enrollment resources, those who remained uninsured were more likely to report not getting the information they needed to sign up, and that signing up was difficult.31,32 MNsure faced well-documented glitches early in the first open enrollment period,33 which might have contributed to concerns about not having sufficient information to enroll in coverage. As the Marketplace continues to address technical and operational problems, some of these concerns might be mitigated. However, some might still benefit from the option to request in-person assistance while browsing the Web site to gain personalized support to understand their options and complete the enrollment process.

Our study suggests that affordability will be an ongoing challenge to increased and sustained insurance coverage. Among individuals who remained uninsured, affordability was the primary reason cited for not obtaining coverage. However, most of these people reported incomes that implied eligibility for public coverage or subsidized plans on the marketplace. We speculate that at least some of those who remained uninsured looked at the Web site, but were deterred by the prices. Because only 4% of those who remain uninsured sought in-person assistance, the majority did not get one-on-one support to understand their insurance options, such as free or subsidized coverage.

A clear benefit of gaining health insurance coverage is improved perceived financial protection from health care costs.31 Those who gained coverage were more likely to feel well protected when it came to their health care needs and were less likely to worry that their health care needs would not be paid for. That said, more than half of those who gained coverage reported some concerns about financial protection, indicating that having insurance coverage did not remove all concerns about cost.32,34,35

Together, our results provided a story of tempered success in the first year following full implementation of the ACA. The good news was that outreach and enrollment efforts seemed to have worked; most individuals had looked for coverage, heard of MNsure, and had gone to the Web site. In addition, the in-person assister program seemed to be a key factor in helping some gain insurance. However, many of the remaining uninsured still struggled with the enrollment process or reported being deterred by the cost of coverage.

Looking forward, making enrollment and health insurance less complicated will be an important focus for Minnesota. This includes making people aware of their options, including free and subsidized coverage and also providing information on the value of health insurance. Obtaining coverage requires individuals to make affordability tradeoffs that are complicated for even the most savvy consumer, and enrollment assistance needs to help consumers weigh these tradeoffs. Recent research indicated that people weighing these options might benefit from the information and advice available through direct personalized assistance either in-person or through call centers.15 Because it works to help individuals consider coverage options and navigate the enrollment process, continued funding for one-on-one assistance will be an important focus for Minnesota. Another option is to support new technologies like advanced-decision support technologies. Picwell is currently working with MNsure to develop a Web-based tool that would support health plan selection based on current and future spending, risk tolerance, and individual preferences.36 Because most of the previously uninsured visited the Web site, and only 4% of those who remained uninsured sought in-person help, this seems like a promising strategy.

Although in-person assistance or advanced Web-based tools might help individuals understand and weigh the value of coverage options, they only address individuals’ need for information, not the issue of affordability, which was the underlying narrative of our study. Although Minnesota had some of the lowest Marketplace premiums, they are coupled with higher deductibles.37 This was reflected in the fact that almost half of those who gained coverage still worried about paying for at least some health care needs. Therefore, regardless of how well information was presented and whether it was understood, insurance must be within the financial reach of individuals to cover the remaining uninsured. To affect this barrier, the federal government and states will have to continue to address coverage costs and identify solutions for those who may want to sign up for coverage yet lack the means or financial arrangements (e.g., credit card, savings, or checking account) necessary to make premium payments.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Reform Assistance Network, with support from the Minnesota Department of Health.

We extend our sincere gratitude to Colin Planalp of SHADAC for helping us tell our story clearly. Finally, this study would not be possible without the survey staff at SSRS/Social Science Research Solutions and the careful oversight of Susan Sherr and David Dutwin.

Human Participant Protection

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota institutional review board; participants provided consent before responding to the survey.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services. 2014 poverty guidelines. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/2013-poverty-guidelines. Accessed December 30, 2014.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2015. Medicaid & CHIP: December 2014 monthly applications, eligibility determinations and enrollment report. Available at: http://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/program-information/downloads/december-2014-enrollment-report.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Washington, DC: HHS; 2015. ASPE issue brief: health insurance marketplace 2015 open enrollment period: January enrollment report. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2015/MarketPlaceEnrollment/Jan2015/ib_2015jan_enrollment.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long SK, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S et al. The Health Reform Monitoring Survey: addressing data gaps to provide timely insights into the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(1):161–167. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins S, Rasmussen P, Doty M. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2014. Gaining ground: Americans’ health insurance coverage and access to care after the Affordable Care Act’s first open enrollment period. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2014/jul/1760_collins_gaining_ground_tracking_survey.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy J. Washington, DC: Gallup; 2014. In US, uninsured rate holds at 13.4% Available at: http://www.gallup.com/poll/178100/uninsured-rate-holds.aspx. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommers BD, Epstein AM. Medicaid expansion—the soft underbelly of health care reform? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2085–2087. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Menlo Park, CA: KFF; 2013. Key lessons from Medicaid and CHIP for outreach and enrollment under the Affordable Care Act. Available at: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/8445-key-lessons-from-medicaid-and-chip.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mach A, Redhead S. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Services; 2014. Federal funding for health insurance exchanges. Available at: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43066.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooperative Agreement to Support Establishment of the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Exchanges, Funding Opportunity Number: IE-HBE-12-001(CFDA 93.525) Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Menlo Park, CA: KFF; 2013. Helping hands: a look at state consumer assistance programs under the Affordable Care Act. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/helping-hands-a-look-at-state-consumer-assistance-programs-under-the-affordable-care-act. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.MNsure. Awarded contracts. Available at: https://www.mnsure.org/about-us/rfp-contract/contracts.jsp. Accessed December 30, 2014.

- 13.MNsure. St. Paul, MN: MNsure; MNsure releases outreach and enrollment grant RFP [press release] May 5, 2014. Available at: https://www.mnsure.org/news-room/news/news-detail.jsp?id=486-128573. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MNsure. MNsure 2014 outreach and enrollment grantees. Available at: https://www.mnsure.org/images/2014-Outreach-Enrollment-Program-Grantees.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2015.

- 15.Zuckerman S, Karpman M, Blavin F, Shartzer A. Navigating the Marketplace: How Uninsured Adults Have Been Looking for Coverage. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, Health Policy Center; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Menlo Park, CA: KFF; 2013. California’s uninsured on the eve of ACA open enrollment: the Kaiser Family Foundation baseline survey. Available at: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/8485-f-californias-uninsured-on-the-eve-of-aca-open-enrollment.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Call KT, Spencer D, Alarcon Espinoza G, Kemmick Pintor J, Lukanen E, Dutwin D. Methods Brief: Minnesota Health Insurance Transitions Study (MN-HITS) Minneapolis, MN: SHADAC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Deerfield, IL: AAPOR; 2015. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys, 8th edition. Available at: http://www.aapor.org/AAPORKentico/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions2015_8theditionwithchanges_April2015_logo.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Call KT, Blewett LA, Boudreaux M, Turner J. Monitoring health reform efforts: which state level data to use? Inquiry. 2013;50(2):93–105. doi: 10.1177/0046958013513670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Social Science Research Solutions. Media, PA: SSRS; 2013. 2013 Oregon Health Insurance Survey: methodology report. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/oha/OHPR/RSCH/docs/Uninsured/2013_Final_OHIS_Methodology_Report.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.State Health Access Data Assistance Center. Minneapolis, MN: SHADAC; 2014. The State Reform Survey Item Matrix (SRSIM) Available at: http://www.shadac.org/content/srsim. Accessed June 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.State Health Access Data Assistance Center. Minneapolis, MN: SHADAC; 2014. The Marketplace Enrollee Survey Item Matrix (MESIM) Available at: http://www.shadac.org/content/marketplace-enrollee-survey-item-matrix-mesim. Accessed June 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census Bureau. Current population survey health insurance definitions. Available at: https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/methodology/definitions/cps.html. Accessed December 30, 2014.

- 24.Pascale J, Rodean J, Leeman J, Cosenza C, Schoua-Glusberg A. Preparing to measure health coverage in federal surveys post-reform. Inquiry. 2013;50(2):106–123. doi: 10.1177/0046958013513679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Q, Gelman A, Tracy M, Norris F, Galea S. New York, NY: Columbia University; 2012. Weighting adjustments for panel nonresponse. Available at: http://www.stat.columbia.edu/∼gelman/research/unpublished/weighting%20adjustments%20for%20panel%20surveys.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wun L, Ezzati-Rice T, Baskin R . Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. Using propensity scores to adjust weights to compensate for dwelling unit level nonresponse in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Available at: http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/workingpapers/wp_04004.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein R, Proctor S, Boudreault M, Turczyn K. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Healthy People 2010 criteria for data suppression: statistical notes no. 24. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statnt/statnt24.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sonier J, Lukanen E, Blewett L. Minneapolis, MN: State Health Access Data Assistance Center, University of Minnesota; 2014. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Minnesota. Available at: http://www.shadac.org/MinnesotaCoverageReport. Accessed March 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.St. Paul, MN: State of Minnesota; Governor Dayton expedites Medicaid expansion [press release] January 20, 2011. Available at: http://mn.gov/governor/newsroom/pressreleasedetail.jsp?id=9319. Accessed March 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiJulio B, Firth J, Levitt L, Claxton G, Garfield R, Brodie M. Menlo Park, CA: KFF; 2014. Where are California’s uninsured now? Wave 2 of the Kaiser Family Foundation California Longitudinal Panel Survey. Available at: http://kff.org/report-section/where-are-californias-uninsured-now-introduction. Accessed June 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins S, Rasmuessen PW, Doty MM, Beutel S. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2015. The rise in health care coverage and affordability since health reform took effect: findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2014. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/∼/media/files/publications/issue-brief/2015/jan/1800_collins_biennial_survey_brief.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stawicki E, Richert C. What went wrong with the Minnesota Insurance Exchange. Kaiser Health News. Available at: http://kaiserhealthnews.org/news/what-went-wrong-with-the-minnesota-insurance-exchange. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Call KT, McAlpine DD, Garcia CM et al. Barriers to care in an ethnically diverse publicly insured population: is health care reform enough? Med Care. 2014;52(8):720–727. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holahan J, Zuckerman S, Long S, Goin D, Karpman M, Fogel A. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2014. Health Reform Monitoring Survey: pre-reform access and affordability for the ACA’s subsidy-eligible population. Available at: http://hrms.urban.org/briefs/aca-subsidy-eligible-population.pdf. Accessed May 22, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Philadelphia, PA: PRNewswire; Picwell to study impact of advanced decision support technology within state health exchanges [press release] October 8, 2014. Available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/picwell-to-study-potential-impact-of-advanced-decision-support-technology-within-state-health-exchanges-278489481.html. Accessed January 6, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breakaway Policy. Washington, DC: Breakaway Policy Strategies; 2013. Eight million and counting: a deeper look at premiums, cost sharing and benefit design in the new health insurance marketplaces. Available at: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2014/rwjf412878. Accessed December 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]