Abstract

Objectives. We investigated how access to and continuity of care might be affected by transitions between health insurance coverage sources, including the Marketplace (also called the Exchange), Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

Methods. From January to February 2014 and from August to September 2014, we searched provider directories for networks of primary care physicians and selected pediatric specialists participating in Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP in 6 market areas of the United States and calculated the degree to which networks overlapped.

Results. Networks of physicians in Medicaid and CHIP were nearly identical, meaning transitions between those programs may not result in much physician disruption. This was not the case for Marketplace and Medicaid and CHIP networks.

Conclusions. Transitions from the Marketplace to Medicaid or CHIP may result in different degrees of physician disruption for consumers depending on where they live and what type of Marketplace product they purchase.

As the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act1 ushers in a new era in health care coverage and delivery, significant changes to the health insurance landscape have personal implications for individuals whose insurance options change. Many families previously unable to buy coverage in the individual market (because of either affordability or underwriting issues), as well as those previously eligible for but not enrolled in public coverage, may obtain coverage for the first time through health insurance Marketplaces (also called Exchanges, with federal subsidies available to offset premium costs for households with incomes up to 4 times the poverty level) or through an expanded Medicaid program (with eligibility expanded to low-income adults with household incomes below 138% of the poverty level defined by the US Department of Health and Human Services and updated annually).

Changes in income or family size may necessitate transitions between sources of coverage. It is too early to know how many people will need to transition, although a recent study estimated that nearly one third of adults with a family income below 400% of the poverty level would experience a shift in eligibility within 6 months and half would change their eligibility status within a year.2 Such transitions raise concerns about whether individuals or families will be able to access the same physicians if they switch programs.

EVIDENCE FROM THE LITERATURE

Research from a recent literature review has suggested that having a relationship with the same primary care physician (PCP) over time improves quality of care, decreases hospitalizations and emergency visits, and increases patient satisfaction.3 Of particular interest for this study, children reporting a usual source of care are more likely than others to receive recommended preventive services, such as immunizations.4,5 Furthermore, patients report perceiving continuity of care as important, citing the value of long-term relationships with their physicians and their physicians’ personal knowledge of them.6

Moving between insurance programs can result in provider changes if a patient’s original provider does not participate in a network associated with the new program, thus disrupting physician continuity. In a study of children enrolled in Oregon’s Medicaid program, nearly one quarter changed their usual source of care because of changes in insurance, resulting in greater odds of having unmet medical needs, unmet prescription needs, and delayed care.7 Furthermore, in a survey of commercially insured patients in northeast Ohio, patients who reported changing physicians because of an insurance change gave lower scores on all primary care quality measures collected (such as interpersonal communication, physician knowledge of the patient, coordination of care, and continuity of care) than patients who were not forced to change.8

METHODS

To ascertain the degree to which physician continuity may be affected by individuals transitioning between Marketplace, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) coverage, we examined networks of PCPs and several types of pediatric specialists in 6 geographically and programmatically diverse market areas and calculated the degree to which physician networks overlapped across these programs. In 2 of the market areas, we looked at the composition of provider networks 8 months later to determine how networks changed and whether they became more or less similar across programs.

Study Sample

We selected market areas on the basis of several criteria. Most importantly, the markets needed to be located in states that had (1) expanded Medicaid, (2) enrolled at least 60% of its Medicaid population in managed care (to ensure the use of provider networks), and (3) a higher-than-average uninsured rate (to ensure the results would be applicable to the largest population possible). Among states meeting those criteria, we selected 6, including at least 1 from each of the 4 census regions and states with varied Marketplace designs (state based, federally facilitated, or partnership). (The sample size of 6 was determined by available resources.) We also sought diversity in other characteristics that might affect an enrollee’s continuity of care, including average Marketplace premiums, competitiveness in individual insurance markets, and CHIP program type.

The 6 market areas in the study included: Chicago, Illinois; Phoenix, Arizona; Louisville, Kentucky; Baltimore, Maryland; Buffalo, New York; and East Los Angeles, California. (Market areas are listed in order of decreasing population size. All market areas except East Los Angeles were defined by their city limits; East Los Angeles was defined as 2 unique zip codes for data collection purposes.)

In all but 2 of the 6 states, we selected the most populous city to ensure the study results would be applicable to the largest population possible. In 2 states, the most populous city (Los Angeles, CA, and New York, NY) contained more than 1 geographic rating area (state-defined pricing regions for issuers), making the data too complex and fragmented to include in the analysis. Thus, in California, we focused only on East Los Angeles because of its high concentration of low-income individuals. In New York, we selected Buffalo, the next most populous city in the state. Although the places selected are diverse in potentially important ways, they are not intended to be a nationally representative sample. For the 8-month follow-up, we examined networks in Louisville and Buffalo on the basis of the ease of data extraction and because the original findings from these 2 market areas were substantially different. PCP overlap in Buffalo was originally the highest among market areas; overlap in Louisville was approximately the median.

Data

After selecting the 6 market areas, we identified the health insurance issuers (companies offering coverage through the various programs), plans (policies individuals can purchase), and provider networks offered through the Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP in each area. The provider network is the unit of analysis examined in this article because it is the level at which consumers experience differences in provider choice. (An issuer may use the same network for multiple plans.) We distinguish between Marketplace health maintenance organization (HMO) and preferred provider organization (PPO) network configurations because of key differences in their costs and structure. Both HMOs and PPOs have contracts with networks of health care providers and medical facilities to provide care for members at reduced costs. HMOs generally only pay for in-network care and structure their networks narrowly to have tighter control on costs and quality. PPOs offer members more flexibility, including allowing members to see providers outside of the network, generally at a higher cost to the member. In these market areas, managed care organizations that participate in public coverage all operate like HMOs (rather than PPOs). A small number of Marketplace issuers in this study offered point-of-service plans and exclusive provider organizations. Point-of-service plans require members to obtain services through a PCP (or point of service) but offer limited reimbursement for some out-of-network services. For analysis purposes, we categorized point-of-service plans (which were only offered in the Baltimore and Buffalo Marketplaces) as HMO plans because they operate like HMO plans. Exclusive provider organization plans are identical to PPOs, except that no reimbursement is given for out-of-network care; these plans were only offered in Buffalo’s Marketplace and, for analysis purposes, were categorized as PPOs.

We searched online, publicly available provider directories to catalog all PCPs—which we defined as family, general, and internal medicine physicians and pediatricians—and the selected pediatric specialists participating in each network. We were able to find provider directories online for all but 1 of the networks. Despite several requests for a hard-copy version, we were unable to retrieve a copy of the directory, so we were unable to include that network (from an issuer offering Medicaid and CHIP insurance) from the study. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants were excluded from the study because the states have significant variation in whether these providers can serve as PCPs and because we found inconsistencies in how directories listed these particular types of providers. Most online directories are live and can be updated daily. We obtained 2 distinct snapshots of physicians in each market area, from January to February and August to September 2014.

In the absence of commonly used national provider identification numbers, we matched physicians across networks within each market area on the basis of name, assuming that a physician with the same name participating in the same market area was the same person. We considered matching physicians on the basis of name and address, but many physicians reported multiple locations, and we wanted individual physician, not physician location, to be the unit gathered. In the market areas studied, we determined that physicians with identical names were not a large issue. Because physician names were sometimes entered slightly differently by directory (e.g., variable use of middle initials and hyphens) or included what appeared to be typographical errors, we manually reviewed and corrected for these differences. Records for fewer than 5% of physicians required correction. The cleaned directory lists for each issuer were combined to create a single usable list of physicians for each market area.

RESULTS

We found the issuers participating in Medicaid and CHIP in all market areas to be identical and the networks of PCPs and pediatric specialists offered through those networks to be nearly identical (except in Buffalo, where the differences were negligible). This finding suggests that, although some states administer these programs separately, issuers typically treat them as the same program. Furthermore, because the same issuers offer the same networks of providers across the 2 programs, an individual transitioning between Medicaid and CHIP who kept the same issuer would likely be able to maintain access to the same provider network and thus the same physicians. Thus, throughout the remainder of this article, we show Medicaid and CHIP as a combined public coverage unit to simplify analysis.

We present the results of 3 distinct analyses: differences in Marketplace HMO, Marketplace PPO, and public coverage PCP networks in 6 market areas from January to February 2014; changes in physician networks from January and February to August and September 2014 in 2 market areas; and differences in networks for children’s hospitals and selected pediatric specialists in August–September 2014.

Differences in Primary Care Physician Networks

Network size.

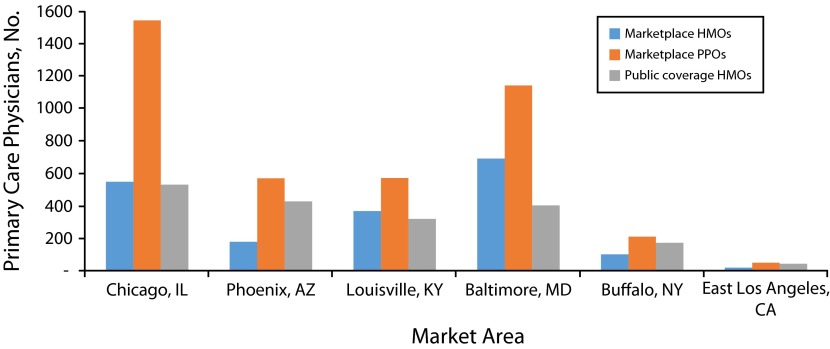

Early on, policymakers voiced concerns about issuers offering narrow Marketplace networks to control costs.9,10 We found that Marketplace PPO networks had the highest average number of PCPs per network in all market areas (Figure 1). When comparing the average size of Marketplace HMO and public networks, we found that Marketplace HMO networks were generally on par with public networks in Chicago, Louisville, and Buffalo. In Phoenix and East Los Angeles, we found public networks were on average substantially larger. In Baltimore, Marketplace HMOs were substantially larger.

FIGURE 1—

Average number of primary care physicians per network, by market area: United States, January–February 2014.

Note. HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization. “Public coverage” includes Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

Transitions from Marketplace to public coverage.

The percentage of Marketplace PCPs that also participate in public coverage was higher among Marketplace HMOs than Marketplace PPOs in all market areas (Figure 2), which means that, despite the fact that Marketplace HMOs have smaller networks than Marketplace PPOs, the overlap between Marketplace HMOs and public networks is greater than the overlap between Marketplace PPOs and public networks. This finding suggests that consumers transitioning to public coverage from a Marketplace HMO plan may be able to keep their PCP more easily than those transitioning to public coverage from a Marketplace PPO, with the magnitude of the difference varying by market area. For example, 97% of PCPs in Marketplace HMO networks in Buffalo also participated in at least 1 public network, compared with 63% of PCPs in Marketplace PPO networks—a difference of 34 percentage points. By contrast, the numbers in Chicago were 72% and 26%, respectively—a 46-percentage-point difference.

FIGURE 2—

Percentage of primary care physicians in a Marketplace (HMO and PPO) network who also participate in a public coverage HMO network, by market area: United States, January–February 2014.

Note. HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization. Public coverage networks include Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program. Market areas are organized from high to low for Marketplace HMO and public coverage overlap.

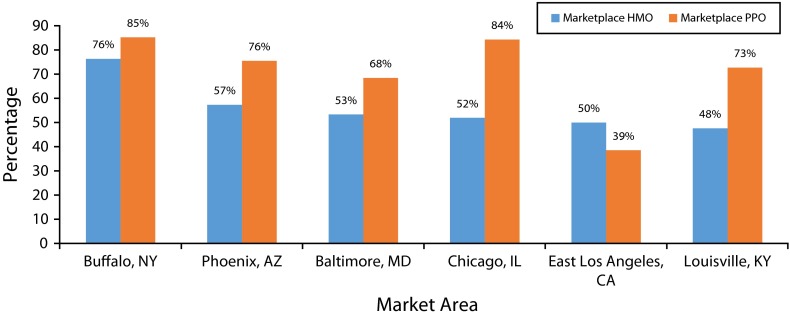

Transitions from public coverage to Marketplace.

In general, we would expect more PCP overlap between public coverage and Marketplace PPOs than between public coverage and Marketplace HMOs because PPOs typically have broader networks. Indeed, the percentage of public coverage PCPs who also participated in a Marketplace PPO was higher than the percentage participating in a Marketplace HMO in all market areas except East Los Angeles (Figure 3). Unlike transitions from the Marketplace to public coverage—in which the overlap between Marketplace HMO and public networks was more influential than the size of the networks—in transitions from public coverage to the Marketplace, the size of the Marketplace PPO network was paramount. The magnitude of the difference again varied by market area. In Buffalo, 76% of public coverage PCPs also participated in a Marketplace HMO and 85% also participated in a Marketplace PPO. In Chicago, the percentages were 52% and 84%, respectively.

FIGURE 3—

Percentage of primary care physicians in a public coverage HMO network who also participate in a Marketplace (HMO or PPO) network, by market area: United States, January–February 2014.

Note. HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization. Public coverage networks include Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program. Market areas are organized from high to low for public coverage HMO and Marketplace HMO overlap.

Change in Primary Care Physician Networks Over Time

To assess how much PCP networks might change over time, we examined networks in Louisville and Buffalo 8 months after the initial snapshot. In both places, the total number of PCPs available in the Marketplace and public networks remained relatively constant, reducing total PCPs by less than 3% and 2%, respectively (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Although the total number of PCPs remained relatively steady, sizable additions and withdrawals occurred in all types of networks examined. Some changed which programs they participated in, meaning the composition of the networks did, in fact, change somewhat substantially. For example, 70 new PCPs (6.5%) entered the sample in Louisville—either representing new physicians moving to Louisville or, more likely, physicians who began accepting insurance from 1 or more of the programs of interest. Ninety-nine PCPs (9.2%) withdrew, meaning they moved away or stopped accepting Marketplace or public insurance. Finally, 95 PCPs (8.8%) changed which programs they participated in—for example, a physician who accepted both Marketplace and public insurance in January and February who later accepted only Marketplace coverage.

These differences in network composition resulted in some changes to the network overlap rates, with no clear patterns emerging as to whether networks across programs became more or less similar over time. Among PCPs participating in Marketplace networks, the percentage participating in Marketplace HMO and PPO networks who also participated in public coverage decreased in Louisville (from 84% to 74% and from 54% to 53%, respectively; Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). In Buffalo, the percentage decreased for Marketplace HMOs and increased for Marketplace PPOs (from 97% to 95% and from 63% to 73%, respectively). In terms of the opposite transition, in Louisville, the percentage of PCPs participating in public coverage that also participated in a Marketplace network increased, from 48% to 56% for Marketplace HMOs and from 73% to 80% for Marketplace PPOs. In Buffalo, the changes were much smaller.

Pediatric Specialist Networks

We analyzed the composition of Marketplace and public networks for children’s hospitals and for the following specialists in each of the 6 market areas from August to September 2014: pediatric cardiologists, pediatric hematologists or oncologists, pediatric nephrologists, pediatric neurologists, and pediatric rheumatologists. We based the set of pediatric specialists of interest on a preliminary literature review and consultation with experts in the field. Considerations included the potential significance of a disruption in care, pediatric specialist types with known physician shortages, and the importance of a child seeing a pediatric specialist (as opposed to a nonpediatric specialist) for that particular type of care. Public networks were, again, nearly identical. Of children’s hospitals that participated in a Marketplace network (either HMO or PPO), 100% also participated in a public network, meaning transitioning from the Marketplace to public coverage was unlikely to be problematic for children from a hospital perspective. Transitioning from public insurance to a Marketplace network (either HMO or PPO) would be similarly straightforward, with all participating in both, except in Chicago, where selecting a Marketplace HMO may limit children’s hospital access.

When looking at pediatric specialists, we found patterns roughly similar to the PCP findings. For example, the percentage of pediatric specialists participating in Marketplace HMO networks who also participated in public networks was higher than the percentage who participated in Marketplace PPO networks and who also participated in public coverage in all market areas, except Baltimore (numbers not shown; East Los Angeles was excluded from this analysis because we found only 1 pediatric specialist located in that market area). The transition from public insurance to the Marketplace is likely easier when selecting a PPO product in most market areas (numbers not shown).

About a third of all networks (Marketplace HMO, Marketplace PPO, and public) considered across market areas included no in-network physicians for at least 1 of the 5 pediatric specialties (Table 1). (We should note that a network without a particular type of pediatric specialist in our data does not mean complete lack of access to that type of physician but rather a lack of access within the city of interest. Patients may have more options if they are able to look outside the city.) The absence of 1 or more category of pediatric specialists was more common among Marketplace networks than among public networks. For example, none of the public networks lacked a pediatric hematologist or oncologist, but one third of Marketplace HMO networks did.

TABLE 1—

Number of Networks Lacking 1 or More Types of Participating Pediatric Specialists: 5 US Market Areas, August–September 2014

| Marketplace |

|||

| Metric | HMO | PPO | Public Insurance HMO |

| Total networks available | 18 | 23 | 24 |

| No. of networks with no | |||

| Pediatric cardiologists | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Pediatric hematologists or oncologists | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Pediatric nephrologists | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Pediatric neurologists | 4 | 5 | 0 |

| Pediatric rheumatologists | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Note. HMO = health maintenance organization; PPO = preferred provider organization. The 5 US market areas were Chicago, IL; Phoenix, AZ; Louisville, KY; Baltimore, MD; and Buffalo, NY. (East Los Angeles, CA, was excluded from this table because we found only 1 pediatric specialist located in the market area.) The same network may be counted multiple times (e.g., a network may lack both pediatric cardiologists and pediatric neurologists). Public insurance includes Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

Consumer Access to Information

Our experience using publicly available information on physician networks illuminated some of the challenges confronting a consumer when researching provider networks. For example, Marketplace Web sites consistently listed issuer and plan names, but they did not consistently list network names. Many issuers offered multiple plans mapping to different networks. For example, 1 Phoenix issuer examined in our study offered 4 Marketplace networks with an average of 4 unique plans per network. To determine whether a particular physician is available in a given plan requires consumers to go to that issuer’s Web site, identify which network maps to the plan of interest, and conduct a search. If consumers are interested in comparing networks offered by the same issuer or across different issuers, they would need to conduct unique searches and compare the output manually.

DISCUSSION

Transitions from the Marketplace to Medicaid or CHIP may result in different degrees of physician disruption for consumers depending on where they live and what type of Marketplace product they chose. Next, we discuss the policy implications of those transitions and what they might mean for consumers.

Primary Care Physician Networks

In all market areas studied, we found that the issuers participating in Medicaid and CHIP were identical and the PCPs participating in their networks were nearly identical, meaning individuals transitioning between Medicaid and CHIP who keep the same issuer will likely have access to the same physician networks. However, individuals moving between the Marketplace and public insurance may experience different degrees of disruption, depending on where they live and whether they select a Marketplace HMO or PPO product. When transitioning between the Marketplace (HMO or PPO) and public coverage, the direction of the transition, the size of the networks, and the percentage of physicians that overlap across networks may all influence consumers’ prospects for continuity of care. In general, selecting a Marketplace PPO in these market areas may be likely to offer consumers more choice in PCPs; however, PPOs may cost more than HMOs and thus be cost prohibitive. Furthermore, although Marketplace PPOs may offer broader networks than Marketplace HMOs, transitioning from a Marketplace HMO to public coverage is likely to be easier because of the high degree of overlap between those types of networks.

Some policy levers are available to ease the transition process for consumers. For example, states operating state-based and partnership Marketplaces can encourage public insurance issuers to participate in the Marketplace (and vice versa), either through incentives or regulation. This may increase the degree of issuer overlap across programs, but it is not a guaranteed mechanism for increasing network overlap, because issuers can and do maintain separate provider networks for their unique products. Issuers themselves could encourage the physicians with whom they contract to participate in all of their product lines to alleviate this problem, although evidence has suggested that low Medicaid reimbursement rates and other administrative barriers, such as payment delays and frequent rejection of claims, may discourage physicians from participating in Medicaid.11 The Affordable Care Act sought to address these problems by increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates for certain primary care services to Medicare levels for 2013 and 20141(§ 1202)). Previous research has shown a positive association between Medicaid physician fees and the percentage of physicians accepting Medicaid patients, although the estimated impact sizes vary.12,13

Another policy option for state governments to consider is adoption of a Basic Health Program (BHP), which was authorized by the Affordable Care Act and made available for states to implement beginning in 2015.1(§ 1331) BHP covers low-income residents through state-contracting standard health plans outside of the Marketplace, using similar contracting and administrative structures as Medicaid and the Marketplace. BHP adoption, particularly if constructed as a Medicaid look-alike, could give consumers access to similar coverage available through public insurance potentially at a lower cost than in the Marketplace. State interest in BHP has thus far been limited because of concerns related to cost, unknown enrollment patterns, and implementation resources.

Issuers are continuing to modify and refine networks for all product types. Overall, in the 2 market areas we investigated over time, we did not observe substantial changes in the total number of PCPs participating, although we did see shifts in physician participation. This reinforces the need for consumers to investigate networks in which their PCPs participate when making health coverage decisions.

Pediatric Specialist Networks

Among pediatric specialists examined, we saw similar participation patterns as were found in the PCP analysis. About one third of all networks considered across market areas had no in-network physicians in at least 1 of the 5 pediatric specialty areas assessed. Although this finding might reflect challenges faced by issuers early on in setting up new networks for the Marketplace, it might also indicate gaps in network adequacy rules or enforcement with respect to the inclusion of pediatric specialists. The federal government sets Marketplace network adequacy standards but gives states much flexibility in interpreting the regulations. Issuers must also comply with state standards in place before the Affordable Care Act. Final rules published by the US Department of Health and Human Services in 2012 elaborate on the minimum network adequacy requirements, stating that Marketplace issuers must maintain provider networks that are

sufficient in numbers and types of providers, including providers who specialize in mental health and substance abuse services, to assure that all services will be accessible without unreasonable delay (45 C.F.R. 156.230).

In some areas, because of varying circumstances, there may be issuers who have a smaller number of in-network pediatric specialists. In those instances, some issuers may arrange for out-of-network pediatric specialty care at in-network pricing on a case-by-case basis. In general, network adequacy requirements do not include specific requirements for pediatric specialists. Developing more stringent network adequacy standards and enforcement mechanisms could help increase pediatric specialist participation in Marketplace networks. However, stricter network adequacy standards place a greater burden on issuers trying to compete on cost and quality, particularly in locations in which few specialists are located.

Consumer Access to Information

Consumers transitioning to or from the Marketplace must access and understand complex information. We found that gathering and comparing information across provider directories is time consuming and requires technical proficiency that many consumers may lack. Working knowledge of the differences among programs, issuers, networks, and plans as well as strong computer skills are needed to navigate provider directories adeptly. Although nearly all directories are publicly available online as searchable databases, the search tools vary greatly by issuer. They do not facilitate clear comparisons of physicians across the same issuer’s different network offerings, much less comparisons across different issuers’ networks. A standardized network search tool on each Marketplace Web site could help consumers and navigators make informed determinations about whether their physicians participate in particular programs or networks, thereby allowing families to more easily maintain physician continuity. At the very least, the Marketplaces should consider publishing the name of the provider network (as it appears on the issuer’s Web site) associated with each plan option.

Limitations

Some limitations of this study relate to the quality of data obtainable from the issuers’ provider directories. Resolving differences in how physician names appeared across directories was a manual process. We cannot be certain that all inconsistencies were identified and correctly resolved. Although we used the information available to consumers at the time of the searches, the Marketplace was new and issuers may still have been refining and finalizing their directories. Thus, we expect that the Marketplace directories might have been less reliable than the public coverage program directories. Our findings show such strong differences between Marketplace and public coverage networks, however, that real differences are likely to persist even if the Marketplace directories continued to be modified.

Marketplace Web sites did not always publish the exact name of the provider network associated with each plan, meaning that we augmented publicly available information by making phone calls to some issuers to determine whether we were navigating the Web site correctly. Furthermore, the data did not allow us to account for the number of enrollees each PCP serves (which would have allowed us to weight more heavily used physicians accordingly), nor for whether PCPs were accepting new patients. Therefore, although we could look at network overlap, we could not calculate the likelihood that a consumer would be able to maintain access to the same physician when transitioning between programs. We should note that all 6 states in this study have continuity-of-care laws or rules that aim to avoid disruptions in care when the physician can no longer see a patient because of a change in health plan or because a provider ceases participation in a provider network. Such rules tend to require plans to continue coverage for treatment for (1) pregnancy, (2) acute illness, or (3) chronic illness (e.g., those that are life threatening, degenerative, or disabling). These laws typically require that plans extend in-network coverage for 60 or 90 days—in the case of pregnancy, through the completion of postpartum care, and for terminal illness, for the remainder of the individual’s life. We do not know when the issuers in this study renew physician contracts or whether renewal is on a rolling or an annual basis. If it was on an annual basis and the renewal date was outside of this study’s window, we may have underestimated the amount of physician turnover. Finally, because this is a small study of 6 metropolitan market areas, results may not be representative of the broader Marketplace and public coverage markets.

Future Areas of Research

Future areas of research could include expanding this type of analysis to include more market areas or additional types of physicians or other health care providers. Another useful area of inquiry would be to investigate whether physicians listed in Marketplace, Medicaid, and CHIP provider directories are accepting new patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (contract HHSP23320095642WC/HHSP23337026T).

Note. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, or Mathematica Policy Research.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed for this article because no human participants were involved.

References

- 1. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111–148, 42 U.S.C. §§ 18001-18121 (2010).

- 2.Sommers BD, Graves JA, Swartz K, Rosenbaum S. Medicaid and marketplace eligibility changes will occur often in all states; policy options can ease impact. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(4):700–707. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, Forster AJ. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(5):947–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allred NJ, Wooten KG, Kong Y. The association of health insurance and continuous primary care in the medical home on vaccination coverage for 19- to 35-month-old children. Pediatrics. 2007;119(suppl 1):S4–S11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PJ, Santoli J, Chu S, Ochoa D, Rodewald L. The association between having a medical home and vaccination coverage among children eligible for the Vaccines for Children program. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):130–139. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandhi N, Saultz J. Patients’ perceptions of interpersonal continuity of care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(4):390–397. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVoe JE, Saultz J, Krois L, Tilltson C. A medical home versus temporary housing: the importance of a stable usual source of care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1363–1371. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kikano GE, Flocke SA, Gotler RS, Stange KC. My insurance changed: the negative effects of discontinuity of care. Fam Pract Manag. 2000;7(10):44–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pear R. Lower health insurance premiums to come at cost of fewer choices. New York Times. September 22, 2013. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/23/health/lower-health-insurance-premiums-to-come-at-cost-of-fewer-choices.html?_r=0. Accessed May 11, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corlette S, Volk J, Berenson R, Feder J. Changing provider networks in marketplace health plans: balancing affordability and access to quality care. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/06/11/changing-provider-networks-in-marketplace-health-plans-balancing-affordability-and-access-to-quality-care. Accessed May 11, 2015.

- 11.Cunningham PJ, O’Malley AS. Do reimbursement delays discourage Medicaid participation by physicians? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(1):w17–w28. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decker S. Acceptance of new Medicaid patients by primary care physicians and experiences with physician availability among children on Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12288. Health Serv Res. 2015; Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Showalter MH. Physicians’ cost shifting behavior: Medicaid versus other patients. Contemp Econ Policy. 1997;15(2):74–84. [Google Scholar]