Abstract

Loss of pancreas β-cell function is the precipitating factor in all forms of diabetes. Cell replacement therapies, such as islet transplantation, remain the best hope for a cure; however, widespread implementation of this method is hampered by availability of donor tissue. Thus, strategies that expand functional β-cell mass are crucial for widespread usage in diabetes cell replacement therapy. Here, we investigate the regulation of the Hippo-target protein, Yes-associated protein (Yap), during development of the endocrine pancreas and its function after reactivation in human cadaveric islets. Our results demonstrate that Yap expression is extinguished at the mRNA level after neurogenin-3-dependent specification of the pancreas endocrine lineage, correlating with proliferation decreases in these cells. Interestingly, when a constitutively active form of Yap was expressed in human cadaver islets robust increases in proliferation were noted within insulin-producing β-cells. Importantly, proliferation in these cells occurs without negatively affecting β-cell differentiation or functional status. Finally, we show that the proproliferative mammalian target of rapamycin pathway is activated after Yap expression, providing at least one explanation for the observed increases in β-cell proliferation. Together, these results provide a foundation for manipulating Yap activity as a novel approach to expand functional islet mass for diabetes regenerative therapy.

The fact that type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) results from loss of a single cell type, the insulin-secreting β-cell, makes this disease the ideal candidate for treatment by new age cell replacement/regenerative medicine techniques (1, 2). Allogeneic islet transplantation in humans has already provided proof-of-principle results demonstrating that restoring physiologically relevant β-cell numbers can result in insulin-independence (3). Source materials for T1D cell replacement therapy are theoretically many, however, only human cadaveric islets are currently used and limitations in supply of donor pancreas tissue have thus far restricted this technique. Strategies aimed at inducing islet/β-cell proliferation would be one mechanism useful for expanding available islet mass and decreasing the demand on donor availability. However, knowledge of the human β-cell cycle is incomplete as are the cell signaling pathways that regulate the critical β-cell cycle machinery (4, 5). A more thorough understanding of these pathways is prerequisite for strategies aimed at inducing islet/β-cell proliferation.

The Hippo-Yes-associated protein (Yap) pathway is a conserved regulator of organ size in Drosophila and mammals (6, 7). In mammals, this pathway functions through a kinase cascade involving the Mst1/2 and Lats1/2 kinases ultimately phosphorylating and inactivating the transcriptional coactivator, Yap, and its paralog, Taz. In the absence of negative regulation, Yap interacts with the TEA-domain (TEAD) family transcription factors and stimulates the expression of genes responsible for cell proliferation and survival (8). Within the developing mouse pancreas, Yap is highly expressed early in development and subsequently decreases as pancreas development proceeds (9, 10). We have previously shown that Yap expression is undetectable within pancreatic islets of both mouse and human origin and that Yap loss during pancreas development coincides with endocrine specification (9). Combined with studies showing endocrine specification drives cell cycle exit, Yap loss may be the precipitating factor in shuttling newly specified β-cells out of the cell cycle during development (11–13).

The goal of this research was to 1) identify how Yap is regulated during development of the endocrine pancreas and 2) to determine whether reconstituting Yap expression within endocrine β-cells is sufficient for stimulating their duplication. Furthermore, we also asked whether β-cell function was maintained within the Yap-expressing islet cells. Our results demonstrate that Yap loss during endocrine cell development is Hippo independent and occurs at the transcriptional level after neurogenin-3 (Ngn3)-dependent specification. Yap loss during endocrine cell development correlates with proliferative decreases in these cells, whereas its activation in human pancreatic islets results in robust β-cell proliferation without affecting β-cell differentiation or functional status. Together, these results identify a pathway useful for induction of β-cell proliferation and an innovative route for increasing mass of this critical cell type for diabetes cell replacement therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, proliferation analysis, and assay of insulin secretion

The mouse pancreas duct cell line (mPAC) and the human pancreas duct cell line (HPDE) were generously provided by Douglas Hanahan (ISREC, Switzerland) and Ming-Sound Tsao (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON), respectively, and maintained as previously described (14, 15). ARIP rat pancreas ductal cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and maintained in complete F12K medium. Min6 and Rin-m5F (RIN) cells were maintained in complete DMEM+25μM mercaptoethanol and RPMI 1640, respectively. Human islets were obtained from Prodo Laboratories and upon arrival, washed and cultured in CMRL media containing 10% fetal bovine serum plus penicillin/streptomycin in 6-well, ultralow adherence plates at a concentration of 1 islet equivalent per 1-μL media (16). Donor characteristics are provided in the Supplemental Table 1. For proliferation analysis, 10μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was included in islet media for 72 hours before harvest. Where indicated, rapamycin was included at 100nM final concentration throughout the islet culture period. For assay of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, mock-transduced or adenovirus-transduced islets (after 72 h of transduction) were incubated for 2 hours in media containing 2.7mM glucose. High-glucose media were then spiked to 16.7mM final concentration and supernatant collected 60 minutes later. Insulin ELISA of supernatants was performed according to manufacturer's protocol (Mercodia, Inc) with insulin concentration normalized to total islet protein concentration.

Adenovirus production and cellular transduction

cDNA encoding YapS127A was subcloned into the pAdenoX-Green vector and recombinant adenovirus generated per manufacturers protocol (Clontech). cDNA encoding human Ngn3 was cloned into the pacAd5CMV-IRES-green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector and adenovirus generated per manufactures protocol (CellBio Labs). Adenovirus was purified using the ViraBind Adenovirus Purification kit and then quantitated using the QuickTiter Adenovirus Quantitation kit (both from CellBio Labs). Control adenovirus expressed GFP singly (Vector BioLabs). For adenoviral transduction, cells were incubated with adenoviruses at a MOI of 25 (cell lines) or 400 (islets) for a minimum of 6 hours. Generation of Yap-expressing Min6 or RIN cell lines is as follows: after 72 hours of culture time, Ad-YapS127A-transduced cells were sorted, using coexpressed GFP, into 3 separate pools of graded GFP expression. YapS127A expression is equivalent to GFP expression in this system. Pools harboring physiologic levels of Yap expression (determined by comparison with mouse [mPAC] or rat [ARIP] pancreas duct cells lines) were then used for further analysis.

RNA and protein analysis

Total RNA from cultured cells was isolated using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). First-strand cDNA was prepared from 1 μg of total RNA with the GoScript kit using random hexamer primers (Promega). One microliter of the cDNA was used as a template for 25-μL PCRs (GoTaq Flexi Polymerase; Promega). PCR products were analyzed on agarose gels using a Gel Doc EZ System (Bio-Rad). Primer sequences are provided in the Supplemental Table 2. All Western blot analyses were performed as described previously (9). For brevity, antibodies used in the Western blotting experiments are included in the Supplemental Table 3.

Pancreas tissue procurement and staining of protein/RNA

Mouse pancreas tissue used in these studies originated from C57Bl6 mice using timed breeding strategies similar to those presented in previous work (9). Production of β-cell-specific Hippo knockout mice involved cross of the conditional Mst1/2 line (17) with the Ins-Cre strain (18). Knockout offspring were born at the anticipated Mendelian frequency and displayed no overt phenotype. All mouse studies were approved by the University Nebraska Medical Center IUCAC. Human fetal pancreas tissue (formalin fixed) was obtained from the Birth Defects Research Laboratory (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) after IRB approval through the University of Nebraska. Staining of tissue sections was described previously (9). For islet staining, islets were harvested, washed, and fixed for 24 hours in 10% formalin/PBS. After fixation, the islets were precipitated (200 g for 3 min), aspirated, washed, and embedded in 1.5% agarose. The agarose plugs were subsequently embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 μm. A complete list of antibodies used in these experiments is provided in the Supplemental Table 3. Assay of RNA expression on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded mouse or human tissue sections used the RNA Scope 2.0 kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics [ACD]) according to the provided instructions. RNA probes, also from ACD were Hs-Yap1 (catalog number 419131), Ms-Yap1 (catalog number 316601), and Ms-Taz (catalog number 316591). Positive control probes were specific for cyclophilin B (PPIB) and obtained from ACD.

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± SD for n independent experiments as described within individual figure legends. Statistical significance was calculated using Student's t test with P ≤ .05 considered significant.

Results

Yap loss during endocrine cell development occurs at the transcriptional level and is independent of canonical Hippo signaling

We and others have previously demonstrated that pan-pancreas loss of Hippo signaling does not affect development of the pancreas endocrine compartment, but instead results in exocrine dysfunction and pancreatitis (9, 10). To confirm this result in the absence of interference from the potentially deleterious pancreatitis phenotype, we deleted the Hippo kinases, Mst1 and Mst2, specifically from insulin-producing β-cells using the Ins-Cre strain (Figure 1A). Highly efficient loss of Mst1/2 from individual islets was noted, whereas an increase in Yap protein was not, confirming a Hippo-independent mechanism likely regulates Yap in pancreas endocrine cells. Yap regulation most often involves its posttranslational modification (ie, phosphorylation) and sequesterization in the cytoplasm (19–21). Given that Yap protein is undetectable within both the nucleus and cytoplasm of β-cells, we next asked whether Yap mRNA remains expressed in these cells. We took advantage of a highly sensitive commercially available in situ hybridization kit and determined relative levels of Yap mRNA expression within the embryonic day (E)16.5 mouse pancreas, using serial sections stained for insulin to demarcate regions harboring newly formed β-cells. Although mRNA expression for the ubiquitous positive control, cyclophilin B (PPIB), was detected throughout individual neo-islet clusters, Yap mRNA was undetectable within the same regions (Figure 1B). Similar to Yap protein expression (Figure 1A) (9, 10), ductal regions contained cells with strong Yap mRNA expression (Figure 1B, inset). We next asked whether Yap regulation in the endocrine pancreas is evolutionarily conserved between mice and humans. Similar to results obtained in the developing mouse pancreas, Yap mRNA is also absent from insulin positive areas in the developing human pancreas (Figure 1C). Lastly, we determined whether the Yap paralog, Taz, displays similar regulation during pancreas development. Taz mRNA expression was also found to be lost during development of the endocrine pancreas and both Yap and Taz protein remain completely undetectable in the commonly used Min6, Ins1, and RIN β-cell lines (Supplemental Figure 1). As a whole, these results suggest an evolutionarily conserved Hippo-independent mechanism is responsible for down-regulating Yap during development of the pancreas endocrine lineage.

Figure 1.

Regulation of Yap in pancreas endocrine cells occurs at the transcriptional level and is independent of canonical Hippo signaling. A, Hippo signaling was disrupted in the β-cell compartment through cross of mice conditional for the Hippo kinases, Mst1 and Mst2 (Mst1/2), to a strain with Cre-recombinase driven by the insulin promoter (Ins-Cre). Efficient Mst1/2 deletion in the pancreas was limited to insulin-positive β-cells. Although Yap expression is readily detectible in pancreas ducts (white arrows), it is absent from both control islets and those harboring loss of Mst1/2, suggesting that Hippo signaling is not responsible for Yap regulation in these cells. B, RNA in situ hybridization was used to determine whether Yap mRNA is expressed in islet cells from postnatal day-2 murine offspring. Although the control probe, targeting the ubiquitously expressed cyclophilin B gene (PPIB), was found to be expressed throughout the pancreas, Yap mRNA expression was much more limited. Specifically, Yap was highly expressed in pancreas duct cells (red box, inset) and completely absent from regions harboring insulin-positive β-cells (black box, inset). C, Similar to results obtained in the mouse, Yap mRNA expression is also absent from insulin-positive regions in 72dpc human pancreas. Serial cut sections were used for the in situ hybridization experiments shown in B and C. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Ngn-3 expression is sufficient for driving Yap loss during endocrine specification and correlates with decreases in cell proliferation

Specification and subsequent development of the pancreas endocrine lineage is completely dependent on the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Ngn3 (22). In mouse pancreas development, we have previously shown that Yap loss and onset of Ngn3 expression occur in similar regions along the pancreas trunk epithelium, a region that harbors bipotent progenitors which give rise to both endocrine and duct cells (9). To determine whether Ngn3 expression and Yap loss occur in parallel within the same cell we used immunofluorescent analysis to colocalize these 2 proteins. Although most the trunk epithelium contained cells with strong Yap nuclear expression, those reactive for Ngn3 contained nuclei devoid of Yap protein (Figure 2A). Because of the cuboidal shape and high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio of these cells, it is difficult to discern whether residual Yap expression occurs in the cytoplasm of Ngn3-expressing cells; high magnification analysis does not suggest this to be the case (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Onset of Ngn3 expression during development of the endocrine pancreas is sufficient for Yap loss and tightly correlates with proliferative decreases in these cells. A, Immunofluorescent colocalization of Ngn3 and Yap protein during development of the E16.5 mouse (top) and 72dpc human pancreas. Although Yap is highly expressed and localized to the nucleus of nearly all pancreas trunk epithelial cells, its expression is absent from those cells containing robust Ngn3 expression. B, Transduction of the mPAC with an Ngn3-GFP-coexpressing adenovirus was used to determine whether Ngn3 expression is sufficient for Yap down-regulation. Forty-eight hours after transduction, cells were FACS sorted for GFP expression and subsequently used for Western blot analysis (left) or reverse transcription PCR analysis (right). NeuroD1, a well-known Ngn3 target gene was robustly increased after Ngn3 expression, whereas expressions of both Yap and its paralog, Taz, were rapidly down-regulated. C and D, Cell proliferation was analyzed during E16.5 mouse pancreas development and correlated with Yap expression. Although proliferating Ki67-positive cells are frequent throughout the E16.5 pancreas, Ngn3-positive cells are generally not mitotically active (C). Proliferation rates in Yap-positive vs Yap-negative cells were determined by comparing Yap expression with Ki67 immunoreactivity in the E16.5 pancreas. Roughly half of Yap(+) cells were active in the cell cycle compared with only approximately 10% of Yap(minus) cells. We extended this one step further by comparing levels of proliferation in the 3 major pancreas cell lineages (duct [white dotted line], acinar [“A”], and endocrine [“E”]). Although Yap expression is readily detectible in both duct and acinar cells, it is absent from endocrine cells. Proliferation mirrors this phenomenon as both acinar and duct cells display high rates of proliferation, whereas endocrine cells do not. (n = 3 age-matched embryo sections, ***, P ≤ .01). Scale bars, 50 μm.

To determine whether Ngn3 expression, by itself, is sufficient for Yap loss, we used an in vitro endocrine differentiation system where transduction of the mPAC with Ngn3-expressing adenovirus (Ad-Ngn3) stimulates endocrine cell differentiation (23). Using this model we observed an increase in NeuroD1, a well-known Ngn3-target gene, in the Ad-Ngn3-transduced cells but not in the mock or Ad-Con-transduced cells (Figure 2B). Levels of both Yap and Taz protein were dramatically decreased after Ngn3 expression, whereas levels in Ad-Con-transduced cells mirrored those observed in the parental mock-transduced cells (Figure 2B). Based on our in vivo findings showing that transcription of Yap is terminated after endocrine cell development, we next determined whether Yap mRNA is decreased after transduction with Ad-Ngn3. Similar to results with protein, NeuroD1 message was dramatically increased after Ngn3 expression, whereas Yap and Taz mRNA were decreased compared with Ad-Con- or mock-transduced mPAC cells (Figure 2B). These results were confirmed using a secondary cell line, human pancreas duct cell line, and suggest that onset of Ngn3 expression is sufficient for driving decreases in Yap expression during pancreas endocrine cell development (Supplemental Figure 2).

The so-called “secondary transition” of pancreas development occurs from roughly E13 to E17 in the mouse and is characterized by substantial proliferation and differentiation. However, once endocrine cells are specified, they experience a near complete loss of proliferation (11–13). With this knowledge in hand we asked whether Yap expression correlated with proliferation in the E16.5 mouse pancreas. Although acinar and duct cells still expressed readily detectible Yap protein, its expression was completely absent from endocrine cell areas (Figure 2D and Supplemental Figure 2). This observation mirrored proliferation rates in these cells as roughly one third of both the acinar and duct cell lineages were active in the cell cycle, whereas less than 5% of endocrine cells were actively cycling (Figure 2D). We then determined levels of proliferating Yap-positive vs Yap-negative cells at the same developmental time point (independent of specific cell type). Although nearly half of Yap-positive cells were active in the cell cycle, only approximately 10% of Yap-negative cells were found to be actively cycling (Figure 2D). Together, these observations identify a tightknit association between Yap expression and proliferation in the developing pancreas, especially within the endocrine compartment. Importantly, the relationship between onset of Ngn3 expression, Yap loss, and decreases in endocrine cell proliferation were also observed during development of the human pancreas (Supplemental Figure 2).

YapS127A expression stimulates robust cell proliferation of human islets

Mature pancreatic β-cells, which are lost or nonfunctional in human diabetes, do not readily proliferate under normal conditions or after injury (4, 5). Based on the tight relationship between Yap expression and proliferation observed in pancreas development, we asked whether reconstituting Yap expression in human cadaver islets was sufficient for driving β-cell proliferation. At high multiplicity of infection, adenoviruses have previously been shown to readily transduce cells throughout intact human cadaver islets (24–27). Our experiments use adenovirus (Ad-Yap) that coexpresses both GFP and a constitutively active Yap mutant (YapS127A), both under control of the ubiquitous cytomegalovirus promoter. Control virus (Ad-Con) expresses GFP singly. Both Ad-Con and Ad-Yap efficiently transduced cells throughout individual human cadaver islets, with preference for cells located at the periphery (Figure 3A). Verification of efficient transduction allowed us to next test whether YapS127A expression affected islet biology. We first assessed Yap signaling to determine whether YapS127A was indeed functional within transduced human cadaver islets. As demonstrated in Figure 3B, YapS127A protein was expressed throughout both the cytoplasm and nucleus of transduced cells. Substantial overlap between Yap and TEAD transcription factors were noted within the nucleus, suggesting that expression of Yap-target genes was likely. In agreement with this, we observed potent expression of the Yap-TEAD-target genes, connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and Cyr61 in Ad-Yap-transduced islets and not those transduced with control virus (Figure 3C). Interestingly, protein expression of one or more of the TEAD transcription factors was also increased, suggesting possible positive feedback in this pathway (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Transduction of human cadaver islets with constitutively active YapS127A is sufficient to drive expression of known Hippo/Yap-target genes. A, Both the control virus (Ad-Con)- and YapS127A-expressing adenovirus (Ad-Yap) readily transduce cells throughout intact human cadaveric islets as monitored by coexpressed GFP. B, Nuclear colocalization of transduced YapS127A with endogenous TEAD transcription factors suggests that transcription of Yap-target genes is likely. Interestingly, TEAD-expressing cells were more often found at the islet exterior and roughly correlated with Yap expression. C, Expression of known Yap-target genes was assessed in islet extracts using Western blot analysis. Although the β-cell-specific protein Pdx1 was found at equal levels in both Ad-Con- and Ad-Yap-transduced islets, expression of the Yap targets, Cyr61 and CTGF, were dramatically increased in only those transduced with YapS127A. Unexpectedly, yet repetitively, levels of one or more TEAD transcription factors were also increased. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Having verified functional Yap-TEAD signaling in the Ad-Yap-transduced islets, we next determined whether transduced endocrine cells reenter the cell cycle. In contrast to Ad-Con-transduced cells, Ad-Yap islet cells reenter the cell cycle as determined by incorporation of the nucleotide analog BrdU (Figure 4, A and C, and Supplemental Figure 3). Specifically, insulin(+) endocrine cells that additionally express YapS127A show increased BrdU labeling compared with insulin(+) cells that do not express Yap (Figure 4A). Because BrdU incorporation only denotes those cells undergoing DNA replication, or may have undergone DNA repair (27), we verified our results with 2 other hallmark proliferation markers, Ki67 and PCNA (Figure 4B). Controls not expressing YapS127A were found to contain Ki67- and PCNA-positive cells; however, these were not found within hormone reactive regions (Figure 4B). Ad-Yap-transduced islets demonstrated strong increases in both Ki67 and PCNA expression within insulin positive cells verifying that β-cells reenter the cell cycle after YapS127A expression (Figure 4, B and C). Because adenoviral transduction is not specific for only β-cells, we next asked whether other endocrine cells are also mitotically responsive to YapS127A expression. As demonstrated in Figure 4D, glucagon-expressing α-cells, like their β-cell counterparts, reenter the cell cycle after YapS127A expression.

Figure 4.

Human β-cells expressing YapS127A reenter the cell cycle and proliferate. A and B, Expression of YapS127A is sufficient to induce de novo cell proliferation within human cadaveric islets as determined by BrdU incorporation and Ki67 and PCNA expression (72 h after infection). White arrows denote proliferating insulin-positive cells. C, Quantitative analysis of islet cell proliferation after YapS127A expression (***, P ≤ .05). Results are the average (±SD) of 3 independent donor islet preparations (n = 3). D, Proliferation is also evident in glucagon-expressing α-cells. Yellow arrow denotes BrdU(+) Yap-expressing α-cell, white arrows denote Yap-negative BrdU(minus) α-cells. E, Yap transduction of whole-human islets leads to up-regulation of the proproliferative c-Myc and cyclin D1 proteins and proliferation-associated phosphorylation of Rb. Scale bars, 50 μm.

To gain further insight into the cell cycle profile of YapS127A-transduced islets, we screened islet extracts with antibodies specific for cell cycle regulatory proteins (Figure 4E). We have previously shown that Hippo loss from the pancreas leads to stabilization of β-catenin and up-regulation of its proproliferative target gene, c-Myc (9). Similar to Hippo loss, both β-catenin and c-Myc were found to be up-regulated in Yap-transduced islets (data not shown and Figure 4E). Entry to the cell cycle is governed by up-regulation of specific cyclin proteins and most important among these are the D-type cyclins, which combine with their kinase counterparts and facilitate exit from the G1 phase and entrance to DNA synthesis. Only in YapS127A-expressing islets were we able to detect cyclin D1 protein, suggesting that these cells were active in the cell cycle (Figure 2E). Cyclin D1 associates with Cdk4/6 and phosphorylates, thus inactivating the cell cycle inhibitor, retinoblastoma protein (Rb). In agreement with this, YapS127A-expressing islet extracts demonstrated strong Rb phosphorylation (Figure 4E). These results suggest that Yap is eliciting a proliferative response through activation of common cell cycle regulatory proteins. Lastly, because Yap serves as an oncogene in certain circumstances and could potentially be activating both proliferation and cell death pathways, we determined whether YapS127A expression is compatible with cell viability. Assay of apoptosis using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling suggested no observable increase in cell death between Ad-Con- and Ad-Yap-transduced islet cells (Supplemental Figure 4).

Yap expression is compatible with β-cell differentiation status and function

Identification that YapS127A expression stimulates β-cell proliferation within human islets and is compatible with cell viability, allowed us to next ask whether YapS127A expression affected general differentiation status of islet β-cells. We focused our attention on comparing Ad-Yap-transduced islets with those transduced with control adenovirus. Overall levels of insulin expression were unaffected between islets that either express or do not express YapS127A protein (Figure 5A). Furthermore, expression of Nkx6.1 and Pdx1, 2 factors essential for β-cell identity and function, were also found to be maintained at levels similar to nontransduced cells (Figure 5A). Moreover, both Pdx1 and Nkx6.1 maintained strong nuclear reactivity and displayed minimal cytoplasmic localization as has been documented during β-cell dysfunction and/or dedifferentiation (28–30). Finally, we determined relative levels of synaptophysin, as this protein marks functional endocrine cells. We did not observe any difference in synaptophysin expression between Ad-Yap- and Ad-Con-transduced islets (Figure 5A). Analysis of islet protein extracts supports our immunofluorescence analysis as total Pdx1 and Glut2 levels remain unchanged between Ad-Con and Ad-Yap islets (Figures 3C and 4E).

Figure 5.

Endocrine differentiation and physiological function is maintained in human islets expressing YapS127A. A, Immunofluorescent colocalization of transduced YapS127A protein with β-cell-specific Nkx6.1 or Pdx1 transcription factors suggests negligible loss of β-cell differentiation in human cadaveric islets, whereas analysis of the endocrine functional marker, synaptophysin, and β-cell functional marker, insulin, suggests overall physiological function remains intact. Ad-Con-transduced islets are shown in the right-hand column for comparison. B, Physiological function of transduced islets was assessed with 2 separate donor islet batches by glucose-stimulated insulin secretion assay. No difference in insulin secretion was observed between mock-transduced islets, Ad-GFP, or Ad-Yap-transduced islets. Each condition was assayed in triplicate with baseline for insulin release being mock infected islets in basal glucose media (2.7mM). Insulin concentration was determined by ELISA and values were subsequently normalized to total islet protein. (Scale bars, 50 μm)

Confirmation that β-cell differentiation status is maintained after YapS127A expression allowed us to next determine whether Yap-transduced islets retain physiological function. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion was assessed in normal islets (mock) or those transduced with control or YapS127A-expressing adenovirus. Islets which had been actively expressing YapS127A for a minimum of 72 hours were used in these assays. Averaged results from duplicate islet donor batches demonstrate that glucose-stimulated insulin secretion remained unaffected by YapS127A expression (Figure 5B). In all cases, a roughly 5-fold increase in insulin secretion was observed after exposure to high-glucose culture media.

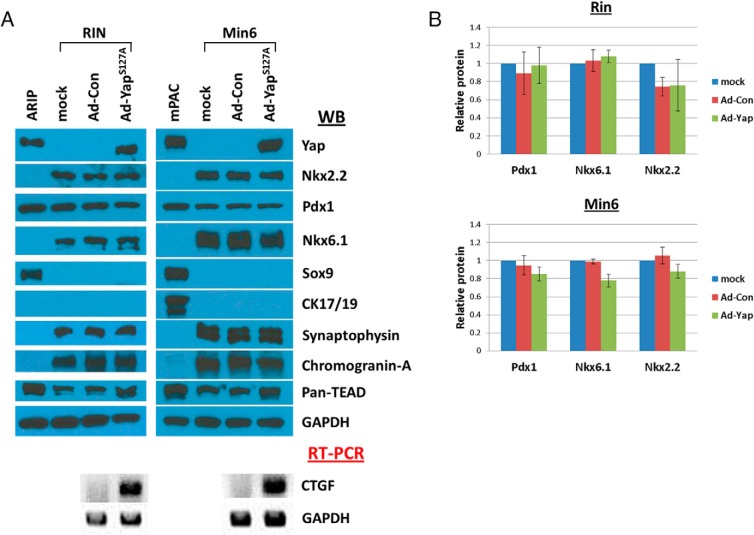

Because transduction of intact islets did not target all cells within a given islet, we confirmed our β-cell differentiation observations using Western blottings of β-cell lines that had been engineered to express physiologically relevant levels of YapS127A protein. Importantly, both of the parental Min6 and RIN β-cell lines express no detectable Yap protein (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure 1). In both instances, levels of endocrine/β-cell markers (Nkx2.2, Pdx1, and Nkx6.1) and functional markers (synaptophysin and chromogranin-A) remained unaffected (Figure 6, A and B). Furthermore, duct markers, such as Sox9 and cytokeratin-17/19 remained undetectable, providing evidence that YapS127A expression does not lead to marked transdifferentiation (Figure 6A). Using expression of CTGF, we asked whether YapS127A was indeed functional within the transduced β-cell lines. Only in the Ad-Yap-transduced cells were we able to detect increases in CTGF expression (Figure 6A). Altogether, these results demonstrate that Yap expression is compatible with islet/β-cell functional status and does not lead to notable dedifferentiation.

Figure 6.

Differentiation status is maintained in YapS127A-expressing β-cell lines. A, Min6 or RIN cells were transduced with YapS127A/GFP coexpressing adenovirus and FACS sorted on GFP expression as described in the Materials and Methods. Protein levels of both β-cell markers (Pdx1, Nkx6.1, and Nkx2.2) and β-cell functional markers (chromogranin-A and synaptophysin) remained relatively unchanged compared with mock- or control-transduced cells. Levels of progenitor/duct cell markers (cytokeratin-17/19 and Sox9) were not increased after YapS127A expression, suggesting negligible β-cell transdifferentiation. Functional activity of YapS127A was verified by presence of the TEAD transcription factors and up-regulation of the Yap-TEAD target gene, CTGF. B, Quantitation of Western blot analysis results for the β-cell transcription factors Pdx1, Nkx6.1, and Nkx2.2 indicates trivial changes in expression of these factors. Results are the average (±SD) of 3 individual experiments (n = 3).

Activated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling in YapS127A-transduced islets contributes to increases in cell proliferation

Yap expression results in activation of proproliferative signaling networks, such as the Wnt/β-catenin and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR pathways (6, 7, 31). Given that activated PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling has recently been shown to induce robust β-cell proliferation in both neonatal and adult mice and that this pathway is hyperactivated in pan-pancreas Hippo knockout mice, we next determined whether components of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling are activated in YapS127A-transduced islets (9, 32). The serine-threonine kinase, Akt, is central to the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and requires phosphorylation at Ser473 for activity. Immunostaining with a Ser473 phospho-specific antibody suggested trivial Akt activity in wild-type and Ad-Con-transduced human cadaveric islets (data not shown and Figure 7A). In contrast, Ad-Yap-transduced islets showed robust Akt activation throughout the YapS127A-expressing cells (Figure 7A). Because Akt activation is upstream of mTOR, we asked whether targets of mTOR signaling were active within Ad-Yap-transduced islets. To this end, we immunostained transduced islets with antibody specific for the phosphorylated form of the S6 ribosomal protein, a downstream target of the mTOR pathway. Ad-Con islets demonstrated basal phospho-S6 staining, however, this was strongly increased in Ad-Yap-transduced islets, specifically within YapS127A-expressing cells (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

YapS127A expression activates the mTOR signaling pathway in human β-cells and is necessary for robust cell proliferation. A, Human cadaveric islets were transduced with control (Ad-Con)- or YapS127A-expressing (Ad-Yap) adenovirus and collected 96 hours later. Activated, Ser473-phosphorylated Akt was absent from control islets but was readily detected within YapS127A-expressing islet cells. Phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 protein, an event downstream of activated mTOR signaling, is robustly increased after YapS127A expression. B, Western blot analysis of intact human islets transduced with control or YapS127A-expressing adenovirus and subsequently cultured with either vehicle control (DMSO) or 100nM rapamycin. Signaling through the mTOR pathway, monitored by S6-phosphorylation status, is efficiently decreased with rapamycin treatment. C and D, Yap-induced β-cell proliferation is partially attenuated by cotreatment of human islets with rapamycin (quantitative analysis is presented as side-by-side experiments using separate islet batches; counted cells per condition are noted on each bar).

To determine whether mTOR signaling plays a functional role in cell proliferation elicited by YapS127A expression, adenoviral-transduced islets were incubated in the presence or absence of the mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin. Treatment of intact islets with rapamycin near completely inhibited phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 protein, suggesting highly efficient inhibition of signaling through the mTOR pathway (Figure 7B). Interestingly, even though Yap signaling likely cross-talks with more than one proproliferative signaling pathway, treatment alone with rapamycin was sufficient for decreasing Yap-induced cell proliferation within human islets (Figure 7, C and D). As a whole, these data define the mTOR signaling pathway as one mechanism contributing to Yap-induced proliferation of human islet/β-cells.

Discussion

Hippo-independent regulation of Yap during pancreas endocrine cell development

The pathway(s) responsible for Yap regulation during tissue development and/or maintenance have thus far identified posttranslational mechanisms with many functioning through the Mst1/2 or Lats1/2 kinases (6, 7). Hepatocytes, which make up the bulk of the mammalian liver, are a perfect example. Here, canonical Hippo signaling is required for maintaining Yap in the inactive state through direct phosphorylation. Hepatocyte-specific loss of either Mst1/2 during development or of the upstream Hippo activator, Neurofibromin-2, in adult cells is sufficient for Yap activation, resulting in expression of known Yap-target genes and subsequent entrance into the cell cycle (17, 33, 34). Within the pancreas, expression of Yap protein is strong in the ductal compartment and weak, albeit detectible, within acinar cells. It would not be surprising if signaling through the Hippo pathway is controlling Yap activity in these cells, however, gene knockout studies in the adult pancreas will be required to test this assumption.

Compared with pancreas exocrine cells, the endocrine compartment, including the insulin-producing β-cells, expresses no detectible Yap protein or mRNA. Also unlike exocrine cells, development of the endocrine lineage depends on expression of neuronal-related genes with Ngn3 initiating these events (22). Yap regulation in endocrine cells might therefore follow a similar path as to what occurs during neuronal differentiation. As such, Zhang et al recently demonstrated that Yap is lost during Ngn 2-dependent neuronal differentiation, Ngn2 is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor very similar to Ngn3 (35). Interestingly, this involved a dramatic (≥75%) decrease in Yap mRNA. Simultaneously, these cells exited the cell cycle, thus recapitulating the same events, we observe during development of the mammalian pancreas (Figure 2). The fact that we observe decreases in both Yap and Taz is intriguing and suggests that elimination of both proteins may be required for proper endocrine cell development. Previous microarray analysis of Ngn3(+) endocrine progenitors in the E15.5 mouse embryo found decreased levels of both Yap (−5.7-fold) and Taz (−9.3-fold) relative to the surrounding Ngn3(minus) pancreas (36). The identity of the factor(s) responsible for Yap/Taz expression in the pancreas remain to be identified; however, progenitor/duct-specific transcription factors, such as Sox9 or Hes1, remain potential candidates as expression of these proteins is also lost after specification of the endocrine pancreas (Supplemental Figure 2) (37, 38).

Yap expression correlates with proliferation in the developing pancreas

Differentiation of progenitor cell populations during mammalian development is often times associated with exit from the cell cycle (39). As mentioned above, this is true for both neuronal cells and pancreas endocrine cells (11–13, 35). Mechanisms responsible for shuttling Ngn3-expressing cells out of the cell cycle include up-regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor, Cdkn1a (p21), and the cell cycle regulator p21 activated kinase-3 (13, 40). Loss of either of these proteins was shown to have a mild effect on the proliferation of newly specified endocrine cells, and the effect of p21 activated kinase-3 deficiency resolved by birth. A role for p21 in regulating proliferation of pancreas endocrine cells is interesting given the known crosstalk between Hippo-Yap signaling and p21 expression and the fact that Yap has recently been shown to regulate cellular senescence via its effect on expression of cell cycle regulatory molecules (41–43). Whether the increases in p21 observed after Ngn3 expression are dependent on Yap loss remains to be determined.

The striking loss of Yap during development of the endocrine pancreas compelled us to verify our findings in roughly equivalent staged human pancreas tissue. Similar to the developing mouse pancreas, Yap expression in human samples was robust, paralleled progenitor markers, and was absent from cells expressing Ngn3 and/or endocrine hormones (Supplemental Figure 2 and Figures 1 and 2). Validating findings in human tissue is of utmost importance given the current uncertainties regarding the requirement of the endocrine master regulator, Ngn3, in mouse vs human pancreas development (44–46). In addition, Ngn3 by itself also differs between mice and humans, as its expression is extremely transient in mouse pancreas development, never overlapping with hormone expression, whereas in humans, Ngn3 expression occurs for much longer periods of time and is frequently detected within hormone-expressing cells (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 2) (47). It is feasible that prolonged Ngn3 expression in newly formed human endocrine cells keeps these cells in a state that is completely refractory to proliferation inputs thus allowing accurate maturation. What specific role Yap (and Taz) play during pancreas development remains to be identified and will require a careful analysis of Yap (and/or Taz) loss-of-function mutants, which to this date not been reported.

Yap expression as a means of stimulating proliferation of functional insulin-producing β-cells

Knowledge of the pathways responsible for regulating proliferation of human β-cells remains unclear, precluding development of methods to stimulate expansion of this critical cell type for diabetes regenerative therapy (4, 5). Using viral transduction methodology, we demonstrate that Yap expression is sufficient for stimulating β-cell proliferation, without negatively affecting β-cell differentiation or functional status. How does Yap expression drive β-cell proliferation? Two or more possibilities may explain this observation. The first is that Yap directly activates genes which stimulate β-cell proliferation. Our results show that canonical Yap-TEAD signaling is activated within Yap-transduced islets. Although the targets of Yap-TEAD-mediating cell proliferation remain somewhat obscure, and may depend on the cell-type of interest, CTGF remains a potential candidate (8). In islet biology, CTGF has already been shown to stimulate islet cell proliferation; however, its function likely depends on islet age (48–50). Other possibilities include cell cycle components, as many of these (eg, Cdk6, FoxM1, cyclin D1, Plk1, etc) are significantly up-regulated in gene arrays of Yap-overexpressing cell lines (8, 43, 51). Lastly, potential for positive feedback in signaling through Yap-TEAD was observed after Yap expression in both β-cell lines and human islets (Figures 3C and 6A). Here, 1 or more of the 4 TEAD transcription factors was found to be up-regulated. Others have noted the same phenomena and TEAD1 and/or TEAD4 have been found to be increased after Yap (and Taz) activation (51).

A second possibility potentially contributing to Yap-induced β-cell proliferation is cross-talk with other proproliferative cell signaling pathways. For example, Yap has been previously shown to be a potent activator of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway (31). In our own hands, we observed strong activation of mTOR signaling within Yap-expressing islet cells. This is significant because activation of the mTOR pathway alone is sufficient for driving proliferation of both juvenile and adult β-cells in the mouse (32). Furthermore, signaling through the platelet-derived growth factor receptor, which activates PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, has recently been shown to control age-dependent proliferation of β-cells (52).

Our work uncovers an approach applicable to targeted expansion of pancreatic β-cells. How can we translate this knowledge into practical solutions for diabetes regenerative therapy? First, targeting the Hippo-Yap pathway has already shown promise in other disease states. As examples, inhibiting Hippo signaling in combination with stimulation of Akt activity has recently been shown to stimulate ovarian follicle growth, which may serve as a potential treatment for infertility (53). Of relation to our own work is the fact that cardiomyocyte-specific Yap expression promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and results in regeneration after cardiac infarction (54, 55). This latter finding is extraordinary given that Yap expression stimulated proliferation without affecting cardiomyocyte differentiation or functional status. This observation in cardiac tissue, combined with our data in human cadaveric islets, suggests compatibility between Yap expression and cell-specific function. Animal models using β-cell-specific Yap expression will be required to determine whether 1) functional status is maintained during longer periods of Yap expression and 2) to determine β-cell proliferative capacity within the native pancreas. In addition, defining the factor directly responsible for Yap regulation within β-cells may well allow direct induction of Yap activity and thus β-cell proliferation. Alternatively, protein delivery methods could be used to deliver Yap directly to isolated islets. This latter possibility has already been shown for Taz, where a cell-penetrating form of the Taz protein was shown to be functional within the human mesenchymal stem cell nucleus and stimulated osteogenesis in a cell-based differentiation model (56). In any case, sustained or temporal Yap expression could boost β-cell numbers to levels sufficient for closing the gap between available pancreas donors and recipients and make islet transplantation a more realistic option for T1D.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Danielle Yarde and Dr Andy Dudley for proofreading the manuscript, other members of the Sarvetnick Lab and members of the Holland Regenerative Medicine Program for helpful discussion and assistance, and the UNMC Tissue Science Facility for assistance in processing samples. The also thank the Birth Defects Research Laboratory at the University of Washington for human pancreas tissue and Dr Randy Johnson (MD Anderson) for providing the conditional Mst1/2 mice.

Author contributions: N.M.G. designed the study, wrote the manuscript, and researched data; B.P.B. and S.U.R.M. contributed to discussion; Z.G. assisted with experiments and data acquisition; and N.E.S. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported by funding from the Kieckhefer Foundation (N.E.S.). N.M.G. is the recipient of an individual postdoctoral fellowship from the National Institutes of Health (DK091991).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ACD

- Advanced Cell Diagnostics

- Ad-Ngn3

- Ngn3-expressing adenovirus

- BrdU

- bromodeoxyuridine

- CTGF

- connective tissue growth factor

- E

- embryonic day

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- mPAC

- mouse pancreas duct cell line

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- Ngn3

- neurogenin 3

- PI3K

- phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- Rb

- retinoblastoma protein

- RIN

- Rin-m5F

- T1D

- type 1 diabetes mellitus

- TEAD

- TEA-domain

- Yap

- Yes-associated protein.

References

- 1. Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;383(9911):69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pagliuca FW, Melton DA. How to make a functional β-cell. Development. 2013;140(12):2472–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(4):230–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kulkarni RN, Mizrachi EB, Ocana AG, Stewart AF. Human β-cell proliferation and intracellular signaling: driving in the dark without a road map. Diabetes. 2012;61(9):2205–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernal-Mizrachi E, Kulkarni RN, Scott DK, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Stewart AF, Garcia-Ocaña A. Human β-cell proliferation and intracellular signaling part 2: still driving in the dark without a road map. Diabetes. 2014;63(3):819–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pan D. Hippo signaling in organ size control. Genes Dev. 2007;21(8):886–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(8):877–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, et al. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 2008;22(14):1962–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. George NM, Day CE, Boerner BP, Johnson RL, Sarvetnick NE. Hippo signaling regulates pancreas development through inactivation of Yap. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(24):5116–5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gao T, Zhou D, Yang C, et al. Hippo signaling regulates differentiation and maintenance in the exocrine pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1543–1553, 1553.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development. 2002;129(10):2447–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Desgraz R, Herrera PL. Pancreatic neurogenin 3-expressing cells are unipotent islet precursors. Development. 2009;136(21):3567–3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miyatsuka T, Kosaka Y, Kim H, German MS. Neurogenin3 inhibits proliferation in endocrine progenitors by inducing Cdkn1a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(1):185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoshida T, Hanahan D. Murine pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma produced by in vitro transduction of polyoma middle T oncogene into the islets of Langerhans. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(3):671–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu N, Furukawa T, Kobari M, Tsao MS. Comparative phenotypic studies of duct epithelial cell lines derived from normal human pancreas and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(1):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boerner BP, George NM, Targy NM, Sarvetnick NE. TGF-β superfamily member nodal stimulates human β-cell proliferation while maintaining cellular viability. Endocrinology. 2013;154(11):4099–4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lu L, Li Y, Kim SM, et al. Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(4):1437–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Postic C, Shiota M, Niswender KD, et al. Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic β cell-specific gene knock-outs using Cre recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(1):305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of YAP. Cell. 2005;122(3):421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, et al. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130(6):1120–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21(21):2747–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gradwohl G, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Guillemot F. Neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(4):1607–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gasa R, Mrejen C, Leachman N, et al. Proendocrine genes coordinate the pancreatic islet differentiation program in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(36):13245–13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karslioglu E, Kleinberger JW, Salim FG, et al. cMyc is a principal upstream driver of β-cell proliferation in rat insulinoma cell lines and is an effective mediator of human β-cell replication. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25(10):1760–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cozar-Castellano I, Takane KK, Bottino R, Balamurugan AN, Stewart AF. Induction of β-cell proliferation and retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation in rat and human islets using adenovirus-mediated transfer of cyclin-dependent kinase-4 and cyclin D1. Diabetes. 2004;53(1):149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fiaschi-Taesch NM, Salim F, Kleinberger J, et al. Induction of human β-cell proliferation and engraftment using a single G1/S regulatory molecule, cdk6. Diabetes. 2010;59(8):1926–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rieck S, Zhang J, Li Z, et al. Overexpression of hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α initiates cell cycle entry, but is not sufficient to promote β-cell expansion in human islets. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(9):1590–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meng Z, Lv J, Luo Y, et al. Forkhead box O1/pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 intracellular translocation is regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase and involved in prostaglandin E2-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Endocrinology. 2009;150(12):5284–5293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hagman DK, Hays LB, Parazzoli SD, Poitout V. Palmitate inhibits insulin gene expression by altering PDX-1 nuclear localization and reducing MafA expression in isolated rat islets of Langerhans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(37):32413–32418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guo S, Dai C, Guo M, et al. Inactivation of specific β cell transcription factors in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3305–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tumaneng K, Schlegelmilch K, Russell RC, et al. YAP mediates crosstalk between the Hippo and PI(3)K–TOR pathways by suppressing PTEN via miR-29. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(12):1322–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang KT, Bayan JA, Zeng N, et al. Adult-onset deletion of Pten increases islet mass and β cell proliferation in mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57(2):352–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song H, Mak KK, Topol L, et al. Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(4):1431–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yimlamai D, Christodoulou C, Galli GG, et al. Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate. Cell. 2014;157(6):1324–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang H, Deo M, Thompson RC, Uhler MD, Turner DL. Negative regulation of Yap during neuronal differentiation. Dev Biol. 2012;361(1):103–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Soyer J, Flasse L, Raffelsberger W, et al. Rfx6 is an Ngn3-dependent winged helix transcription factor required for pancreatic islet cell development. Development. 2010;137(2):203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seymour PA, Freude KK, Tran MN, et al. SOX9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor cell pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(6):1865–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kopinke D, Brailsford M, Pan FC, Magnuson MA, Wright CV, Murtaugh LC. Ongoing Notch signaling maintains phenotypic fidelity in the adult exocrine pancreas. Dev Biol. 2012;362(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buttitta LA, Edgar BA. Mechanisms controlling cell cycle exit upon terminal differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(6):697–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piccand J, Meunier A, Merle C, Jia Z, Barnier JV, Gradwohl G. Pak3 promotes cell cycle exit and differentiation of β-cells in the embryonic pancreas and is necessary to maintain glucose homeostasis in adult mice. Diabetes. 2014;63(1):203–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Muramatsu T, Imoto I, Matsui T, et al. YAP is a candidate oncogene for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(3):389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vigneron AM, Vousden KH. An indirect role for ASPP1 in limiting p53-dependent p21 expression and cellular senescence. EMBO J. 2012;31(2):471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xie Q, Chen J, Feng H, et al. YAP/TEAD-mediated transcription controls cellular senescence. Cancer Res. 2013;73(12):3615–3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McGrath PS, Watson CL, Ingram C, Helmrath MA, Wells JM. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor NEUROG3 is required for development of the human endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 2015;64(7):2497–2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jensen JN, Rosenberg LC, Hecksher-Sørensen J, Serup P. Mutant neurogenin-3 in congenital malabsorptive diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1781–1782; author reply 1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rubio-Cabezas O, Codner E, Flanagan SE, Gómez JL, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Neurogenin 3 is important but not essential for pancreatic islet development in humans. Diabetologia. 2014;57(11):2421–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Salisbury RJ, Blaylock J, Berry AA, et al. The window period of NEUROGENIN3 during human gestation. Islets. 2014;6(3):e954436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gunasekaran U, Hudgens CW, Wright BT, Maulis MF, Gannon M. Differential regulation of embryonic and adult β cell replication. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(13):2431–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Guney MA, Petersen CP, Boustani A, et al. Connective tissue growth factor acts within both endothelial cells and β cells to promote proliferation of developing β cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(37):15242–15247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Riley KG, Pasek RC, Maulis MF, et al. Connective tissue growth factor modulates adult β-cell maturity and proliferation to promote β-cell regeneration in mice. Diabetes. 2015;64(4):1284–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang H, Liu CY, Zha ZY, et al. TEAD transcription factors mediate the function of TAZ in cell growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(20):13355–13362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen H, Gu X, Liu Y, et al. PDGF signalling controls age-dependent proliferation in pancreatic β-cells. Nature. 2011;478(7369):349–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Suzuki N, et al. Hippo signaling disruption and Akt stimulation of ovarian follicles for infertility treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(43):17474–17479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xin M, Kim Y, Sutherland LB, et al. Hippo pathway effector Yap promotes cardiac regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(34):13839–13844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lin Z, von Gise A, Zhou P, et al. Cardiac-specific YAP activation improves cardiac function and survival in an experimental murine MI model. Circ Res. 2014;115(3):354–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Suh JS, Lee JY, Choi YJ, et al. Intracellular delivery of cell-penetrating peptide-transcriptional factor fusion protein and its role in selective osteogenesis. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:1153–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]