Abstract

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that both hyperuricemia and gout increase the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Whether urate crystal precipitation confers a particular risk above what is already inherent in having hyperuricemia is not well established. We conducted this cohort study to establish whether the presence of monosodium urate crystal precipitation per se is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular diseases among hyperuricemic patients.

Methods

We identified hyperuricemic individuals who had joint fluid examinations for urate crystals. Individuals with intra-articular urate crystals were matched by propensity score to individuals without crystals and compared with respect to a composite cardiovascular endpoint. Included in the propensity score model were potential confounders retrieved from four different health care registries.

Results

We identified 862 hyperuricemic patients having urate crystal examination. After propensity score matching, we could include 317 patients with urate crystals matched 1:1 to patients without urate crystals. We found no difference between the two groups with respect to cardiovascular outcomes (hazard ratios = 0.86; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.52 - 1.43) or death (hazard ratio 0.74; CI 0.45 - 1.21).

Conclusion

The presence of urate crystal precipitations does not seem to confer a particular cardiovascular risk in hyperuricemic patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13075-015-0822-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Urate crystal precipitations, Cardiovascular risk, Hyperuricemia

Introduction

Recent epidemiological studies have indicated that hyperuricemia with or without gout increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases and mortality [1–6]. The primary cause of gout is hyperuricemia, and increasing levels of urate increase the risk of monosodium urate (MSU) crystal precipitations, which is the defining criterion of gout [7]. Whether there is an increased cardiovascular risk with asymptomatic hyperuricemia has been heavily debated without any consensus having emerged [8, 9], but the most recent papers have leaned towards the recognition of a true, causal relationship between hyperuricemia and cardiovascular disease [10–12].

Despite the increasing evidence that both hyperuricemia and gout are associated with cardiovascular disease, no studies have, to our knowledge, attempted to address whether MSU precipitation confers a particular risk of cardiovascular disease above what is already inherent in having hyperuricemia. From a pathophysiological viewpoint, such a notion would be plausible. Gouty arthritis is associated with increased acute and chronic inflammation [13], and inflammation is prothrombogenic and can result in ischemic cardiovascular events [14, 15].

We conducted this cohort study to establish whether the presence of MSU crystal joint precipitation per se is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular outcomes among hyperuricemic patients. If a link between MSU precipitation and cardiovascular disease could be established, it would favor a more aggressive approach to urate-lowering therapy in patients with gout [16].

Methods

We conducted this cohort study in Funen County, Denmark (approximately 485,000 inhabitants) using Danish health care registries furnished by the Danish health authorities. We identified all hyperuricemic individuals who had synovial fluid examined for MSU crystals and compared individuals with MSU crystals to those without MSU crystals with respect to the occurrence of cardiovascular outcomes. Confounders were controlled by the use of propensity score matching and multivariable modeling.

Data sources

Denmark offers unique possibilities for epidemiological research with population-based registries that combined with the unique personal identifier, the Danish Central Person Registry Code [17], provide perfect individual-level record linkage. In Denmark, virtually all health services are provided by the public health authorities, which allows true population-based epidemiological studies [18].

Using the central person registry code, we linked the four following registries:

The laboratory database of Odense University Hospital (OUHLab), a clinical laboratorial system that contains information on all blood samples analyzed in various hospital laboratories in the Funen County since November 1992. The OUHLab includes primary and secondary health care providers, for both inpatients and outpatients. It also covers valid information on synovial fluid examinations including MSU crystals since 1999. Trained staff at the OUHLab carried out all MSU crystal examinations. Not covered by the database are some blood samples analyzed at general practitioners’ offices with independent equipment. All urate concentration measurements were covered.

The Odense University Pharmaco-Epidemiological Database is a prescription database holding information on redeemed, reimbursed prescriptions for the citizens of Funen County since 1990 [19]. Data included are identifiers of the prescription holder, a full account of the dispensed product, the date of dispensing and a demographic module with information on birth, death, migration and residency, which allowed appropriate censoring. The product is described in terms of the defined daily dose and the anatomical–therapeutic–chemical (ATC) code [20].

The Funen County Patient Administrative System provides hospital discharge diagnosis for the population of Funen County since 1977 for inpatients and since 1989 for outpatients. The diagnoses are encoded according to the International Classification of Diseases eighth revision (ICD8) until January 1994 and the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD10) thereafter. The International Classification of Diseases ninth revision has never been used in Denmark.

The Danish Register of Causes of Death holds information on all causes of death in Danish citizens, encoded according to the ICD system. It is mandatory by law to complete a death certificate in any case of death in Denmark, and the National Board of Health established the current register in 1875 [21].

Cohorts

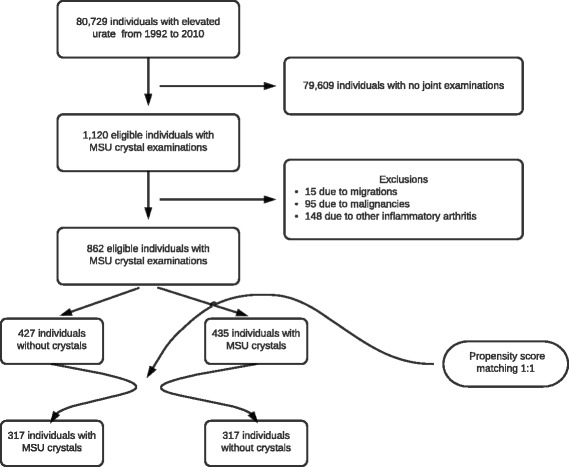

Hyperuricemic individuals were included at the time of their first synovial fluid examination for MSU crystals during the period December 1999–March 2012. We excluded individuals if at the time of inclusion they were younger than 18 years of age or had a malignant diagnosis in the 5 years preceding cohort entry (ICD10 C00–C96 excluding C44). We also excluded individuals with other chronic inflammatory arthritic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis; ICD8 712; ICD10 M05–M07) prior to inclusion (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram. MSU monosodium urate

Individuals entered the MSU crystal cohort if MSU crystals were identified in at least one synovial fluid sample or tophus. Individuals without MSU crystals entered the comparator “no-crystals” cohort. All individuals were followed until the time of any of the following: main outcome (see later), migration, death or end of study period. Furthermore, to avoid immortal time bias, individuals within the no-crystal cohort were censored if later synovial fluid examinations revealed MSU crystals, at which time such individuals would contribute follow-up and events to the MSU crystal exposed cohort. This was the case for 11 (3.5 %) individuals in the no-crystal cohort.

Outcomes

The main outcome was the AntiPlatelet Trialists’ Collaboration (APTC) composite cardiovascular endpoint of nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) (ICD10 I21–I22), nonfatal stroke (ICD10 I60–I64) and cardiovascular death (ICD10 I00–I99, R96–R99) [22].

Secondary outcomes were MI (ICD10 I21–I22), stroke (ICD10 I60–I64), cardiovascular death (ICD10 I00–I99, R96–R99) and all-cause mortality.

Data analysis

Our main analysis was carried out using propensity score as a summary covariate to match patients with and without MSU crystal precipitations. Using logistic regression, we calculated each individual’s propensity to have joint precipitation of MSU crystals based on all relevant cardiovascular risk covariates available at baseline. Each individual with MSU crystals was then matched 1:1 to an individual without crystals, based on their propensity scores. Pairwise nearest-neighbor matching was used, applying a caliper of 0.05 on a probability scale [23]. Variables included in the propensity score are presented in Additional file 1. Because the plasma urate level may play a key role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, we chose to stratify by plasma urate levels, but left this out of the propensity score model for the main analysis. The urate strata were defined by urate <0.30 mmol/l, 0.30–0.36 mmol/l, 0.36–0.42 mmol/l, 0.42–0.48 mmol/l, 0.48–0.54 mmol/l, 0.54–0.60 mmol/l, 0.60–0.68 mmol/l and ≥0.68 mmol/l. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model.

Use of a drug at baseline was defined by the redeeming of a prescription for that particular drug inside 120 days prior to inclusion. Diagnoses were defined as having the ICD8 or ICD10 code for hypertension (ICD8 40; ICD10 I10), for example, at any time before inclusion.

The no-crystal group was set as reference for all analyses.

All statistical analyses were carried out using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Subgroup analyses

We performed preplanned subgroup analyses by age, sex, renal function (using the National Kidney Foundation chronic kidney disease stages [24]), diabetes and hypertension. In all subgroup analyses, the calculated propensity score was added as an independent variable in the Cox regression.

Sensitivity analysis

As shown previously, allopurinol can modify the cardiovascular risk [25–28], and hence previous use of allopurinol was included in the main analyses as part of the propensity score model. To further investigate this issue we ran the analysis excluding users of allopurinol prior to cohort entry. To further investigate the effect of allopurinol we introduced allopurinol as a time-varying exposure. We also ran the analysis including urate levels in the propensity score model without stratification.

Some individuals might develop other inflammatory arthritic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [29] or psoriatic arthritis [30] during the follow-up period, both of which are strongly associated with cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, even though these were excluded at baseline, we conducted an analysis censoring such individuals if they acquired such a diagnosis during follow-up.

Ethics

The project was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. Registry-based studies do not require patient consent or ethical approval in Denmark [31]. After retrieval of source data, all data were anonymized and all analyses were performed on a fully anonymized data set.

Results

In total, we identified 862 individuals with synovial fluid examinations that met our selection criteria. After matching, 634 individuals were included in the study: 317 individuals with MSU crystal precipitations and 317 individuals with no MSU crystals (Fig. 1). Except for urate level, which was not included in the propensity score, the baseline parameters were very well balanced. The characteristics of MSU exposed and unexposed individuals are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of MSU crystal exposed and propensity score matched unexposed individuals

| MSU crystals | No crystals | |

|---|---|---|

| All | 317 (100.0) | 317 (100.0) |

| Male | 277 (87.4) | 275 (86.8) |

| Female | 40 (12.6) | 42 (13.2) |

| Age | 61 (50–74) | 62 (50–74) |

| History of | ||

| Ischemic heart disease | 77 (24.3) | 74 (23.3) |

| Heart failure | 48 (15.1) | 45 (14.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 54 (17.0) | 54 (17.0) |

| Stroke | 38 (12.0) | 34 (10.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 48 (15.1) | 40 (12.6) |

| Hypertension | 109 (34.4) | 100 (31.5) |

| COPD | 33 (10.4) | 30 (9.5) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||

| 0 | 147 (46.4) | 152 (47.9) |

| 1 | 62 (19.6) | 62 (19.6) |

| 2 | 39 (12.3) | 41 (12.9) |

| ≥3 | 69 (21.8) | 62 (19.6) |

| Current drug use (baseline) | ||

| Urate-lowering drugs | 49 (15.5) | 46 (14.5) |

| Diabetes drugs (ever use) | 41 (12.9) | 33 (10.4) |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 36 (11.4) | 34 (10.7) |

| ADP-receptor inhibitor | 8 (2.5) | 6 (1.9) |

| Low-dose ASA | 64 (20.2) | 56 (17.7) |

| Dipyridamole | 11 (3.5) | 11 (3.5) |

| Digitalis | 28 (8.8) | 29 (9.1) |

| Nitrates | 15 (4.7) | 15 (4.7) |

| Thiazide diuretics | 27 (8.5) | 28 (8.8) |

| Loop diuretics | 86 (27.1) | 85 (26.8) |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 15 (4.7) | 14 (4.4) |

| Beta blockers | 61 (19.2) | 60 (18.9) |

| Calcium antagonists | 45 (14.2) | 46 (14.5) |

| RAS blockers | 104 (32.8) | 101 (31.9) |

| Statins | 64 (20.2) | 56 (17.7) |

| COPD drugs | 33 (10.4) | 32 (10.1) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 56 (17.7) | 56 (17.7) |

| NSAIDs | 166 (52.4) | 161 (50.8) |

| Blood measurements (baseline) | ||

| Urate level | 0.53 (0.46–0.61) | 0.43 (0.38–0.50) |

| Urate level <0.30 mmol/l | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Urate level 0.30–0.36 mmol/l | 7 (2.2) | 28 (8.8) |

| Urate level 0.37–0.42 mmol/l | 43 (13.6) | 129 (40.7) |

| Urate level 0.43–0.48 mmol/l | 72 (22.7) | 65 (20.5) |

| Urate level >0.48 mmol/l | 195 (61.5) | 95 (30.0) |

| eGFR | 68 (51–83) | 70 (53–81) |

| High HbA1c (>6.5 %) | 36 (11.4) | 26 (8.2) |

| High total cholesterol (>5 mmol/l) | 64 (20.2) | 67 (21.1) |

| Proteinuria | 43 (13.6) | 38 (12.0) |

Data presented as n (%) or median (IQR)

ADP adenosine diphosphate, ASA acetyl salicylic acid, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, IQR interquartile range, MSU monosodium urate, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, RAS renin–angiotensin system

For MSU exposed and unexposed, the event rates were 45 per 1000 person-years and 34 per 1000 person-years respectively. Cox proportional hazard regression for MSU exposed individuals demonstrated an HR stratified for urate levels for APTC events of 0.86 (95 % CI 0.52–1.44) compared with the unexposed group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular events among propensity score-matched MSU crystal exposed and unexposed individuals

| MSU crystals | No MSU crystals | HR (95 % CI) | HR (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (events / person-year) | (events / person-year) | no stratification by urate level | stratified by urate level | |

| APTC | 46 / 1026 | 34 / 1009 | 1.33 (0.85–2.07) | 0.86 (0.52–1.43) |

| Nonfatal MI | 11 / 1026 | 9 / 1009 | 1.22 (0.50–2.94) | 1.04 (0.37–2.90) |

| Nonfatal stroke | 17 / 1026 | 11 / 1009 | 1.50 (0.70–3.20) | 1.13 (0.49–2.61) |

| CV death | 18 / 1026 | 14 / 1009 | 1.27 (0.63–2.56) | 0.59 (0.26–1.32) |

| All-cause mortality | 46 / 1026 | 40 / 1009 | 1.14 (0.75–1.74) | 0.74 (0.45–1.21) |

APTC AntiPlatelet Trialists’ Collaboration, CI confidence interval, CV cardiovascular, HR Hazard ratio, MI myocardial infarction, MSU monosodium urate

The no-crystal group was set as reference

For the outcomes of strokes and MIs alone, no associations with the presence of MSU crystals were found (Table 2).

For cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality among MSU crystal exposed individuals compared with nonexposed individuals the HR was 0.58 (95 % CI 0.26–1.31) and 0.74 (95 % CI 0.45–1.21) respectively (Table 2).

We failed to identify any subgroups associated with altered cardiovascular risk attributable to the presence or absence of MSU crystal precipitation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular events of MSU crystal exposed and unexposed by subgroups

| MSU crystals | No crystals | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (events / person-years) | (events / person-years) | PS adjusted* | |

| All | 46 / 1026 | 34 / 1009 | 0.86 (0.52–1.43) |

| Age <60 | 14 / 698 | 4 / 577 | 1.31 (0.42–4.15) |

| Age 60–79 | 15 / 240 | 20 / 370 | 0.79 (0.36–1.76) |

| Age 80+ | 17 / 88 | 10 / 62 | 0.79 (0.31–1.97) |

| Male | 40 / 951 | 31 / 896 | 0.82 (0.47–1.41) |

| Female | 6 / 75 | 3 / 113 | 1.87 (0.33–10.57) |

| No previous APTC | 30 / 950 | 24 / 958 | 0.92 (0.48–1.74) |

| Only previous APTC | 16 / 76 | 10 / 51 | 0.73 (0.28–1.94) |

| CKD 4 + 5 | 8 / 41 | 3 / 74 | 2.57 (0.57–11.55) |

| CKD 3 | 18 / 190 | 11 / 164 | 1.24 (0.54–2.86) |

| CKD 2 | 8 / 580 | 19 / 611 | 0.35 (0.13–0.89) |

| CKD 1 | 10 / 163 | 1 / 131 | 3.72 (0.44–31.23) |

| DM | 11 / 103 | 9 / 102 | 0.79 (0.28–2.23) |

| No DM | 35 / 923 | 25 / 907 | 0.93 (0.51–1.69) |

| Hypertension | 22 / 245 | 10 / 214 | 1.69 (0.76–3.78) |

| Normotensive | 24 / 781 | 24 / 795 | 0.64 (0.32–1.26) |

APTC AntiPlatelet Trialists’ Collaboration, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease stages, DM diabetes mellitus, MSU monosodium urate, PS propensity score

*All subgroups are PS adjusted. The no-crystal group was set as reference

When changing the exclusion criteria to comprise previous allopurinol users, the presence of MSU crystals had a significant protective effect on cardiovascular death, while other outcomes remained nonsignificant. The analysis introducing time-varying allopurinol exposure and other sensitivity analyses did not change the results (see Additional file 2).

Discussion

We have shown that, among hyperuricemic individuals, MSU crystal precipitation does not influence the risk of cardiovascular events when other important prognostic factors such as urate levels are adjusted for.

In contrast to our findings, most studies have reported increased cardiovascular risk among gout patients [4, 5, 32]. These studies, however, do not rely on gout being diagnosed according to international guidelines, but are instead based on either self-reported gout or serial measurement of elevated urate or a combination of different measures [4, 5, 32].

Strengths

Our study included all individuals with joint fluid sample for MSU crystals during a 12-year period in Funen County, Denmark. This region has a stable population and we were able to account for migration during the study period on the individual level. In contrast to most other studies, our study is based solely on individuals with joint fluid or tophi examinations for MSU crystals [4, 5, 32], which is in line with international recommendations for gout diagnosis [7, 33]. We had access to all blood samples including MSU crystal determinations of every patient. In addition, we had full coverage of admissions, outpatient visits, prescription data and causes of death.

Limitations

Data on some potential confounders were not available, most importantly smoking status, which is a well-known risk factor for ischemic heart disease [34]. However, to our knowledge, there is no association between smoking and MSU precipitation for a given elevated urate level. Consequently, smoking is unlikely to be an important confounder in our study.

The final number of eligible individuals was small compared with the large source population the sample was derived from. This was primarily due to the small number of joint fluid and tophi samples made for MSU crystal determinations. The small number of MSU crystal determinations is surprising, given that a definite diagnose of gout is based on the presence of MSU crystal deposition [7] and more than 4000 individuals from the Funen population redeemed at least one prescription for the urate-lowering drug allopurinol during 2010 [35].

We did not have access to the indication for the joint fluid examinations. Individuals who undergo this procedure are likely to have a swollen joint and hence some type of arthritis. If the primary causal pathway between gout and cardiovascular disease is mediated through joint inflammation, we might have underestimated the true effect of MSU precipitation, since our reference cohort to some extent had also been affected by inflammation. We attempted to address this by excluding subjects with other established chronic arthritis, but we cannot rule out that there is some residual bias towards the null.

Finally, with a known link between gout and cardiovascular disease, there might be more focus on cardiovascular health in the gout patients. We believe, however, that our very hard endpoints would come to medical attention under all circumstances, whether the patients had gout or not.

Our results can be interpreted in one of four ways. First, the presence of MSU crystals might not influence the cardiovascular disease risk, and the increased risk of cardiovascular disease among gout patients is mediated through other modes of action than the low-grade inflammation induced by crystal deposition [36]. Second, there might be a contribution of urate precipitation to the cardiovascular risk of a gout patient [37], but it is too small to be measured in our setup, given that hyperuricemic patients already have a clearly elevated risk and given the somewhat limited power in our study. Third, synovial fluid examinations do not have perfect sensitivity [38, 39]. We can therefore not rule out that some individuals in the no-crystal group did in fact have MSU crystal precipitations. However, only 2 % (28 out of 1566) of negative first fluid examinations in our material showed positive urate precipitation at a later examination. Finally, even though we excluded patients with other inflammatory arthritis, the no-crystal group could possibly be even more burdened with systemic inflammation [40] than the MSU crystal group, since the indication for joint fluid examinations for crystals not only includes crystal precipitation diseases but also co-examinations of patients suspected to suffer from other arthritis or from infectious joint disease.

Conclusion

The presence or absence of MSU crystal precipitations in hyperuricemic individuals does not seem to be important for individuals’ cardiovascular risk. Future studies hopefully will reveal the pathophysiological mechanism behind the increased risk of cardiovascular diseases among gout patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to appreciate the valuable help validating and quality controlling the STATA programming used in this study performed by Morten Olesen, data manager at the University of Southern Denmark.

This work represents independent research funded by the University of Southern Denmark. The University of Southern Denmark had no part in the planning and execution of this study or in the decision to publish this study.

Abbreviations

- APTC

AntiPlatelet Trialists’ Collaboration

- ATC

Anatomical–therapeutic–chemical

- CI

Confidence interval

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ICD8

International Classification of Diseases eighth revision

- ICD10

International Classification of Diseases 10th revision

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- MSU

Monosodium urate

- OUHLab

Laboratory database of Odense University Hospital

Additional files

Is a table presenting additional information on the variables included in the propensity score model. (DOCX 20 kb)

Presents the results from the sensitivity analyses. (DOCX 113 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

All authors completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf) and declare no support from any organization for the submitted work. KSL and JH have participated in research projects funded by Menarini, with grants paid to institutions where they have been employed, and received personal fees. JH has participated in research projects funded by Nycomed/Takeda and personal fees for teaching. HL has received honoraria and/or participated in research projects funded by Berlin-Chemie/Menarini, Eli Lilly, MSD, Roche and Pfizer, but has no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. AP declares that he has no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KSL designed the study, collected the data, carried out the data management together with the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. AP contributed to the design of the study, helped with the statistical analyses and helped with the draft of the manuscript. HML helped to conceive the study and participated in the design of the study. JH conceived the study, helped with collection of data and contributed to the draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Contributor Information

Kasper Søltoft Larsen, Email: kaslarsen@health.sdu.dk.

Anton Pottegård, Email: apottegaard@health.sdu.dk.

Hanne Lindegaard, Email: hanne.lindegaard@rsyd.dk.

Jesper Hallas, Email: jhallas@health.sdu.dk.

References

- 1.Kim SY, Guevara JP, Kim KM, Choi HK, Heitjan DF, Albert DA. Hyperuricemia and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:170–80. doi: 10.1002/acr.20065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SY, Guevara JP, Kim KM, Choi HK, Heitjan DF, Albert DA. Hyperuricemia and risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:885–92. doi: 10.1002/art.24612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Jacobs DR, Jr, Gaffo AL, Gross MD, Goff DC, Jr, Carr JJ. Longitudinal association between serum urate and subclinical atherosclerosis: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. J Intern Med. 2013;274:594–609. doi: 10.1111/joim.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo CF, See LC, Luo SF, Ko YS, Lin YS, Hwang JS, et al. Gout: an independent risk factor for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Rheumatology. 2010;49:141–6. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnan E, Baker JF, Furst DE, Schumacher HR. Gout and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2688–96. doi: 10.1002/art.22014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarson LE, Hider SL, Belcher J, Heneghan C, Roddy E, Mallen CD. Increased risk of vascular disease associated with gout: a retrospective, matched cohort study in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:642–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, Bardin T, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part I: diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1301–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culleton BF, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Levy D. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:7–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-1-199907060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feig DIKD, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovacular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Ruiz F, Martínez-Indart L, Carmona L, Herrero-Beites AM, Pijoan JI, Krishnan E. Tophaceous gout and high level of hyperuricaemia are both associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:177–82. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neogi T, George J, Rekhraj S, Struthers AD, Choi H, Terkeltaub RA. Are either or both hyperuricemia and xanthine oxidase directly toxic to the vasculature? A critical appraisal. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:327–38. doi: 10.1002/art.33369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borghi C, Rosei EA, Bardin T, Dawson J, Dominiczak A, Kielstein JT, et al. Serum uric acid and the risk of cardiovascular and renal disease. J Hypertens. 2015;33:1729–41. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:499–516. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-7-200510040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pai JK, Pischon T, Ma J, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, Joshipura K, et al. Inflammatory markers and the risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2599–610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiong AY, Brieger D. Inflammation and coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pascual E, Andrés M, Vela P. Gout treatment: should we aim for rapid crystal dissolution? Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:635–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thygesen LC, Ersboll AK. Danish population-based registers for public health and health-related welfare research: introduction to the supplement. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):8–10. doi: 10.1177/1403494811409654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaist D, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish prescription registries. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology . Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2011. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish register of causes of death. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):26–9. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collaboration AT. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration BMJ 1994. Br Med J. 1994;8:81–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rassen JA, Shelat AA, Myers J, Glynn RJ, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. One-to-many propensity score matching in cohort studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:69–80. doi: 10.1002/pds.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foundation NK. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noman A, Ang DS, Ogston S, Lang CC, Struthers AD. Effect of high-dose allopurinol on exercise in patients with chronic stable angina: a randomised, placebo controlled crossover trial. Lancet. 2010;375:2161–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60391-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300:924–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei L, Mackenzie IS, Chen Y, Struthers AD, MacDonald TM. Impact of allopurinol use on urate concentration and cardiovascular outcome. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;71:600–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Verdalles U, Ruiz-Caro C, Ampuero J, Rincon A, et al. Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2010;5:1388–93. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01580210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason JC, Libby P. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic inflammation: mechanisms underlying premature cardiovascular events in rheumatologic conditions. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:482–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horreau C, Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Barnetche T, Misery L, Cribier B, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:12–29. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Bronnum-Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):12–6. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnan ESK, Neaton JD, Grandits G, Kuller LH, MRFIT Research Group Long-term cardiovascular mortality among middle-aged men with gout. Arch Internal Med. 2008;168:1104–10. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sivera F, Andres M, Carmona L, Kydd AS, Moi J, Seth R, et al. Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout: integrating systematic literature review and expert opinion of a broad panel of rheumatologists in the 3e initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:328–35. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Njølstad I, Arnesen E, Lund-Larsen PG. Smoking, serum lipids, blood pressure, and sex differences in myocardial infarction: a 12-year follow-up of the finnmark study. Circulation. 1996;93:450–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Organisation is Statens Serum Institut. Medstat.dk. http://www.medstat.dk/en/viewDataTables/medicineAndMedicalGroups/{%22year%22:[%222010%22],%22region%22:[%225%22],%22gender%22:[%22A%22],%22ageGroup%22:[%22A%22],%22searchVariable%22:[%22people_count%22],%22errorMessages%22:[],%22atcCode%22:[%22M04A%22,%22M04AA01%22],%22sector%22:[%220%22]}. Accessed 3 Feb 2015.

- 36.Kelkar A, Kuo A, Frishman WH. Allopurinol as a cardiovascular drug. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19:265–71. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318229a908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park JJ, Roudier MP, Soman D, Mokadam NA, Simkin PA. Prevalence of birefringent crystals in cardiac and prostatic tissues, an observational study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005308. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swan A, Amer H, Dieppe P. The value of synovial fluid assays in the diagnosis of joint disease: a literature survey. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:493–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lumbreras B, Pascual E, Frasquet J, Gonzalez-Salinas J, Rodriguez E, Hernandez-Aguado I. Analysis for crystals in synovial fluid: training of the analysts results in high consistency. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:612–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.027268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wasko MCM. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:390–7. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]