Abstract

Background

Behavioral addiction research has been particularly flourishing over the last two decades. However, recent publications have suggested that nearly all daily life activities might lead to a genuine addiction.

Methods and aim

In this article, we discuss how the use of atheoretical and confirmatory research approaches may result in the identification of an unlimited list of “new” behavioral addictions.

Results

Both methodological and theoretical shortcomings of these studies were discussed.

Conclusions

We suggested that studies overpathologizing daily life activities are likely to prompt a dismissive appraisal of behavioral addiction research. Consequently, we proposed several roadmaps for future research in the field, centrally highlighting the need for longer tenable behavioral addiction research that shifts from a mere criteria-based approach toward an approach focusing on the psychological processes involved.

Keywords: behavioral addictions, everyday behaviors, mental health, psychopathology, DSM, diagnosis

Imagine the following situation: DC is a 26-year-old man, currently PhD student (third year) in a prestigious university and has an outstanding track record, since he already has first-authored seven peer-reviewed articles. Yet, despite this promising profile, DC is constantly overwhelmed with intrusive and obsessive work-related thoughts. He checks his mailbox night and day, waiting for potential editorial responses about submitted papers, and constantly monitors his bibliometric performance. Since the beginning of his third year, he has been spending a huge amount of time browsing scientific professional network (e.g., ResearchGate) to compare his performance with those of his colleagues, and feels very excited each time he got new citations. When he feels sad or anxious, to get quick relief, he compulsorily overchecks his CV, last publication, and bibliometric indicators. He unsuccessfully tried to reduce these habits and to diminish his work charge due to incoming conflicts with both his family and friends (e.g., stop working on the weekend). Over the years, he lost some friends and progressively became aware that spending all his time to increase his academic CV will not help him making new ones. He wants to publish more and more, and this is the main interest in his life. Now it is rather clear that this PhD student meets the criteria for a new subtype of workaholism called “Research Addiction”. No matter if he is still living alone with his father at the age of 26. No matter if he was exposed to severe psychological abuse by his mother during his entire childhood and has never been in a relationship. No matter if he is characterized by a narcissistic personality. Yes, it does definitively fit with the criteria for “Research Addiction”.

Without any doubt, we assume that any mental health scholar or practitioner, irrespective of his/her clinical experience, should casually laugh in reaction to the aforementioned definition. Yet this description should not appear as totally unrealistic; there are unfortunately more than enough recent publications that created innovative yet absurd addictive disorders as we just did. The difference is that these papers did not intend to make it as a spoof. Consequently, in this article, we will discuss how the use of atheoretical and confirmatory approaches in the understanding of excessive behaviors might result in the identification of such awkward “new” behavioral addictions. As we will argue, many of these resulting constructs have neither specificity nor external and clinical validity. Just as we did through our fictive new addictive disorder, this could weaken and shatter rather than improve the understanding and the soundness of clinical directions in behavioral addiction research.

Behavioral Addictions – A Plague of Our Era?

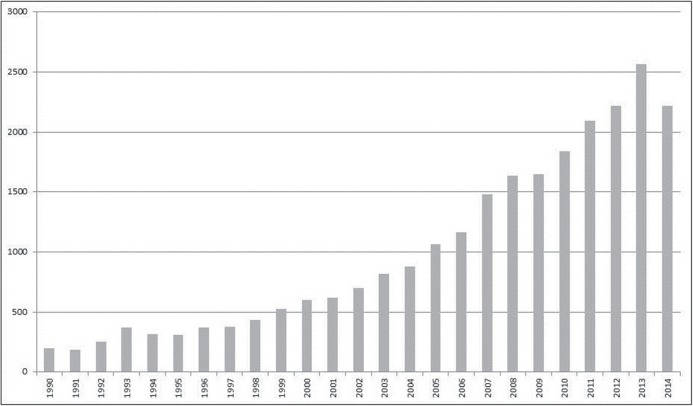

In a seminal work, Isaac Marks (1990) introduced the construct of “non-chemical addictions”. Since Marks’ initial proposal, the addiction research field has endorsed the term “behavioral addiction”, leading to the flourishing accretion of publications (see Figure 1) in key journals in the addictive behaviors research field (e.g., Addiction, Addictive Behaviors, Psychology of Addictive Behaviors). Likewise, since 2012, this enthusiasm has culminated through the enactment of Journal of Behavioral Addictions, a peer-review journal entirely assigned to this concept.

Figure 1.

Behavioral addiction papers published between 1990 and 2014

Note: The research was performed on PUBMED. All articles included mentioned either “behavioral addiction” or “behavioural addiction” as keywords. The highest number of published papers was in 2013 (n = 2563), the year in which the DSM-5 was released. The research was performed in February 2015.

In 2013, a major step towards the recognition of behavioral addictions as psychiatric diagnoses has been reached when “pathological gambling”, renamed “gambling disorder”, was aligned alongside other addictive behaviors in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013). It is here important to mention that decades of empirical research have been conducted before this disorder was officially recognized as an addictive disorder in the DSM-5. Crucially, this change in the classification of gambling disorder was fostered by an accumulation of data supporting similarities with substance addictions. For instance, akin neurobiological alterations were found in gambling and substance disorders (e.g., Grant, Brewer & Potenza, 2006; Potenza, 2008). Likewise, analogous impairments in cognitive mechanisms were identified, including high-level of impulsivity, poor top-down executive control, myopia toward delayed outcomes of choices, and over-sensitivity to addiction-related cues (e.g., Clark, 2010; Goudriaan, Oosterlaan, de Beurs & van den Brink, 2006). Further ammunitions for skeptics came from the recent inclusion in DSM-5 Section III (i.e., emerging measures and models) of another type of behavioral addiction, namely “Internet Gaming Disorder”. This inclusion is disputable and maybe premature, since there are several classification inconsistencies in prior studies as well as poor evidence regarding its etiology and course (Petry & O’Brien, 2013; Schimmenti, Caretti & La Barbera, 2014). However, this inclusion has already resulted in several epidemiological studies and research programs testing the fuzzy boundaries of this new addictive disorder (Ko et al., 2014; Rehbein, Kliem, Baier, Mössle & Petry, 2015).

Capitalizing upon the growing evidence that linked gambling disorder (and, to a lesser extent, Internet-related disorders) to substance use disorder, scholars have conceptualized a wide range of daily behaviors as prospective “new” behavioral addictions. Most of the time, this was based on the observation that excessive involvement in those activities is associated with key addiction symptoms such as apparent tolerance and withdrawal, loss of control, craving, cognitive salience, or mood regulation. Examples of dysfunctional conducts that are often described as behavioral addictions include (but are not limited to) hyper-sexuality, compulsive buying, binge eating, excessive work involvement (“workaholism”), or excessive physical exercise (Demetrovics & Griffiths, 2012). In fact, according to the criteria commonly used to identify behavioral addictions, it is likely that the excessive involvement in any type of activity can be considered as a psychiatric disorder (see Mihordin, 2012, for a critical discussion and an illustration applied to model railroading). This phenomenon is not anecdotic and is susceptible to result in a severe overpathologization of everyday behaviors.

How to Create New Diagnoses Based on Old Recipes?

The principle behind the creation of new behavioral addictions diagnoses is often quite straightforward and mostly follows an atheoretical and confirmatory approach consisting in three steps. First, based on anecdotal observations, the targeted behavior is a priori considered as an addictive behavior. Then, screening tools are developed according to the traditional substance abuse criteria. Eventually, studies are conducted to determine whether risk factors (e.g., biological, psychosocial) known to play a role in the development and maintenance of substance addictions (e.g., impulsivity traits, attentional biases) are associated with the new addictive disorder.

Although this three-step approach can be highlighted in numerous attempts to identify and characterize new behavioral addictions (for an illustration applied to mobile phone, see Billieux, Philippot et al., 2014), we decided to rely here on a prototypical illustration provided by Targhetta, Nalpas and Perne (2013), where they proposed that the high commitment in Argentine tango can be viewed as a behavioral addiction.

The first step of the approach – i.e. the adoption of a confirmatory approach derived from an anecdotal observation – is well identified in the introduction when the authors describe the way they discovered a case of an Argentine tango addict.

“At the end of a 10-day tango festival, RT [one of the authors of the paper] noticed a dancer presented by the tango teacher as the only dancer who attended the milonga (place for the tango dancing) every night from the opening to the end of the session. RT developed a friendly relationship with this dancer and throughout their discussions RT suspected this dancer could be “addicted” to tango. Therefore, RT proposed to the dancer to conduct a complete interview, aiming to verify this hypothesis […] (p. 179).”

Based on this initial observation, they decided to carry on an exploratory survey to determine the prevalence and characteristics of Argentine tango addiction. This last point brings us to the second step of the approach, which is the development of a screening instrument based on the hypothesis that excessive involvement in Argentine tango falls under the spectrum of addictive disorders. Here, Targhetta et al. (2013) have developed a questionnaire based on both DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence and Goodman’s (1990) criteria for addictive disorders. As an illustration, Goodman’s criteria E1 (cognitive salience) and E6 (giving up of recreational, occupational or social activities) were translated into the following item: “I organize my vacation in relation to tango dancing”.

Although developing items assessing loss of control, negative outcomes, craving, withdrawal, or mood modification with respect to any kind of behaviors is usually pretty straightforward, it is here worth noting that the challenge is quite harder when it comes to conceptualizing and operationalizing the dimension of tolerance, one of the key features of addiction. Several unfortunate proposals can be identified in the literature. For example, in a highly cited editorial, Block (2008) proposed that tolerance, in the framework of Internet addiction, “is reflected by the need for better computer equipment, more software, or more hours of use” (p. 306). Another example is when Chóliz (2010) argued that tolerance, in the framework of mobile phone addiction, results in “a gradual increase in mobile phone use to obtain the same level of satisfaction, as well as the need to substitute operative devices with the new models that appear on the market” (p. 374). Clearly, such proposals unfortunately index the poor operationalization of these constructs that often characterizes the translation of the biomedical substance abuse into excessive behaviors. Facing the same challenge, Targhetta and colleagues (2013) assessed Argentine tango tolerance with the following item:“At the beginning of tango dancing, I needed to increase my time of dancing (excepted that devoted to learning)”. Obviously, the need to increase the time spent in a specific behavior can be driven by various motives, especially at the early stages of involvement, and these motives are mostly unrelated to tolerance symptoms. For example, they might be related instead to the development of new competencies and skills, which can represent a powerful reinforcement and can increase self-efficacy and self-esteem. As an illustration, no one would argue that an adolescent boy who starts playing guitar or piano for hours and hours and finds much pleasure in doing this is developing tolerance towards the behavior and/or “music addiction”. Moreover, if such behavior helps the adolescent to feel accepted by his peers, or to impress the girl he likes, no one would say that the excessive behavior is dysfunctional or testifying the development of an addiction.

The third step consists in establishing the biopsychosocial correlates of the new identified behavioral addiction by relying on available evidence in substance addiction (or more strongly established behavioral addiction like disordered gambling). Unsurprisingly, these studies almost systematically emphasized moderate to strong relationships between the targeted constructs (e.g., impulsivity traits) and the presence of addiction symptoms. Indeed, as the items assessing the targeted construct were based on the substance abuse framework, it is obvious that correlations with established risk factors for substance disorders will be found. In the case of tango addiction, it can easily be hypothesized that items such as those developed by Targhetta and colleagues (2013) will correlate with constructs such as impulsivity (e.g., items assessing loss of control), sensation seeking (e.g., items assessing hedonic aspects of tango), and neuroticism (e.g., items assessing mood regulation or stress reduction).

Today, the behavioral addiction research field is invaded by an increasing number of studies that creates new psychiatric disorders by endorsing concepts and models that were based on decades of research and were validated for other disorders (mainly substance use, gambling, and Internet gaming disorders). The intrinsic problem of such an atheoretical and confirmatory approach is that it lacks specificity. Thus, based on deductive quantitative studies, new behavioral addictions are described, along with their diagnostic criteria and prevalence in the community. Nonetheless, at the same time, we cruelly lack a theoretically sound model that can specify the unique factors and processes involved, as well as of preliminary qualitative studies that allow understanding the phenomenology and specificity of these problematic behaviors. Moreover, these studies often rely on the assumption that, because the new category they developed only concerns a small part of the whole sample, it does identify disorder. However, statistical deviance alone often fails to identify disorders. Not all disorders are rare (e.g. nicotine addiction, concerning a third of the adult population worldwide), and conversely most rare conditions (e.g., very high intelligence or a virtuosity in piano playing) are not disorders (McNally, 2011). Eventually, most studies conducted to identify new behavioral addictions fail to consider two factors that are in our view mandatory to define a pathological condition, namely functional impairment (i.e. significant deleterious impact on the daily life) and stability of the dysfunctional behavior. With regard to these particular issues, a recent 5-year longitudinal study (Konkolÿ Thege, Woodin, Hodgins & Williams, 2015) shed some light on the natural course and impact of several behaviors often considered as behavioral addictions (i.e., exercising, sexual behavior, shopping, online chatting, video gaming, problem eating behaviors). This study showed that the excessive involvement in the targeted behaviors (reflected by self-reported functional impairment) tends to be fairly transient for most individuals. Importantly, such type of data supports the view that excessive behaviors are often context-dependent, and that spontaneous recovery is frequent (for similar findings in the field of gambling disorders, see Slutske, 2006).

Syndromes Versus Processes – Clinical Implications

The “addiction model” is nowadays frequently applied to excessive behaviors. This phenomenon is largely explained by accumulating evidence suggesting an overlap among social, psychological and neurobiological factors involved in the etiology of substance and behavioral addictions (i.e. the third step of the approach described above). The main consequence of such an approach is that individuals who exhibit behavioral addiction symptoms are usually treated with standardized interventions that have been proven effective for patients presenting substance addiction issues. In fact, such an approach, which is diagnostic-centered, might lead to neglecting the key psychological processes (motivational, affective, cognitive, interpersonal, and social) sustaining the dysfunctional involvement in a specific conduct (Dudley, Kuyken & Padesky, 2011; Kinderman & Tai, 2007).

As an illustration, recent research supports the view that considering the function of multiplayer online games (MOG) is fundamental to understand their excessive use. Accordingly, identifying the various individual motives that drive online gaming is a requirement for the understanding of a dysfunctional usage and the elaboration of tailored psychological interventions (Billieux et al., 2013; Demetrovics et al., 2011; Schimmenti & Caretti, 2010). In the same vein, recent studies have evidenced that similar symptoms (e.g., loss of control over gaming or negative outcomes resulting from over-involvement) are involved in distinct online gaming motives. While dysfunctional gaming may result from a desire of game achievement (e.g., owning a powerful avatar or becoming the master of a recognized guild, see Billieux et al., 2013), it can also be conceived as an avoidance strategy to face negative life events (e.g., the loss of a job, the confrontation to a trauma) or social anxiety (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014; Schimmenti, Guglielmucci, Barbasio & Granieri, 2012). Consequently, each of these subtypes will require distinct and individualized psychological interventions (Billieux, Thorens et al., 2015). At a more global level, a decade of both qualitative and empirical research supports that problematic involvement in MOG depends on a constellation of factors that are unique to this activity and not necessarily relevant when considering other types of “Internet addictions” (for instance, cybersex or social networks problematic use; Billieux, Deleuze et al., 2014).

To conclude, we would like to emphasize that the objective of the current paper was neither to minimize the obvious negative outcomes and psychological distress that can result from the dysfunctional involvement in specific activities, nor to refute the notion that these disorders can in some cases be conceptualized (and treated) as addictive behaviors. Nonetheless, our major aim was first to emphasize how everyday life behaviors tend to be too easily overpathologized and considered as behavioral addictions. Consequently, we centrally wanted to point out the multi-faceted nature and heterogeneity of these disorders that is too often neglected in favor of a simplistic symptomatic description.

Authors’ contribution

The first author had the initial ideas and decided to write this paper. The first author invited the other authors to contribute. All authors substantially contributed to the writing of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

Joël Billieux and Pierre Maurage are granted by the Belgium National Lottery for research on gambling disorder. Joël Billieux is granted by the European Commission for Research on the Problematic usage of information and communication technology (“Tech Use Disorders”; Grant ID: FP7-PEOPLE-2013-IEF-627999). Pierre Maurage (Research Associate) and Alexandre Heeren (Senior Research Fellow) are funded by the Belgian National Foundation for Scientific Research (F.R.S.-FNRS, Belgium). Alexandre Heeren is also funded by the Belgian Foundation “Vocatio” (Scientific Vocation).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Deleuze J., Griffiths M. D. & Kuss D. J. (2014). Internet gaming addiction: The case of massively multiplayer online role playing games. In El-Guebaly N., Galanter M. & Carrá G. (Eds.), The textbook of addiction treatment: International perspectives (pp. 1515–1525). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Philippot P., Schmid C., Maurage P., de Mol J. & van der Linden M. (2014). Is dysfunctional use of the mobile phone a behavioural addiction? Confronting symptom-based versus process-based approaches. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. Epub ahead of print, doi: 10.1002/cpp.1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., Thorens G., Khazaal Y., Zullino D., Achab S. & van der Linden M. (2015). Problematic involvement in online games: A cluster analytic approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J., van der Linden M., Achab S., Khazaal Y, Paraskev-opoulos L., Zullino D. & Thorens G. (2013). Why do you play World of Warcraft? An in-depth exploration of self-reported motivations to play online and in-game behaviours in the virtual world of Azeroth. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Block J. J. (2008). Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 306–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chóliz M. (2010). Mobile phone addiction: A point of issue. Addiction, 105, 373–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. (2010). Decision-making during gambling: An integration of cognitive and psychobiological approaches. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365, 319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetrovics Z. & Griffiths M. D. (2012). Behavioral addictions: Past, present and future. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1, 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetrovics Z., Urbán R., Nagygyörgy K., Farkas J., Zilahy D., Mervó B., Reindl A., Ágoston C., Kertés A. & Harmath E. (2011). Why do you play? The development of the motives for online gaming questionnaire (MOGQ). Behavior Research Methods, 43, 814–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley R., Kuyken W. & Padesky C. A. (2011). Disorder specific and trans-diagnostic case conceptualisation. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. (1990). Addiction: Definition and implications. British Journal of Addiction, 85, 1403–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan A. E., Oosterlaan J., de Beurs E. & van den Brink W. (2006). Neurocognitive functions in pathological gambling: A comparison with alcohol dependence, Tourette syndrome and normal controls. Addiction, 101, 534–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. E., Brewer J. A. & Potenza M. N. (2006). The neurobiology of substance and behavioral addictions. CNS Spectrum, 11, 924–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of Internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kinderman P. & Tai S. (2007). Empirically grounded clinical interventions: Clinical implications of a psychological model of mental disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 35, 1–14 [Google Scholar]

- Ko C.-H., Yen J.-Y, Chen S.-H., Wang P-W., Chen C.-S. & Yen C.-F. (2014). Evaluation of the diagnostic criteria of Internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5 among young adults in Taiwan. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 53, 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkolÿ Thege B., Woodin E. M., Hodgins D. C. & Williams R. J. (2015). Natural course of behavioral addictions: A 5-year longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks I. (1990). Behavioural (non-chemical) addictions. British Journal of Addiction, 85, 1389–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally R. J. (2011). What is mental illness? Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Mihordin R. (2012). Behavioral Addiction—Quo Vadis? The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 200, 489–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry M. N. & O’Brien C. P. (2013). Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5. Addiction, 108, 1186–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza M. N. (2008). The neurobiology of pathological gambling and drug addiction: An overview and new findings. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363, 3181–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehbein F., Kliem S., Baier D., Mössle T. & Petry N. M. (2015). Prevalence of Internet Gaming Disorder in German adolescents: Diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a statewide representative sample. Addiction. Epub ahead of print, doi: 10.111/add.12849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A. & Caretti V. (2010). Psychic retreats or psychic pits? Unbearable states of mind and technological addiction. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A., Caretti V. & La Barbera D. (2014). Internet Gaming Disorder or Internet Addiction? A plea for conceptual clarity. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 11, 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A., Guglielmucci F., Barbasio C. & Granieri A. (2012). Attachment disorganization and dissociation in virtual worlds: A study on problematic Internet use among players of online role playing games. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 9, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Slutske W. S. (2006). Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: Results of two US national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targhetta R., Nalpas B. & Perney P (2013). Argentine tango: Another behavioral addiction? Journal of Behavioral Addictions , 2, 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]