Abstract

As applications for IVF have expanded over the years, so too have approaches to controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) for IVF. With this expansion and improved knowledge of basic reproductive biology, there is increasing interest in how COS practice influences IVF outcomes, and whether or not specific treatment scenarios call for personalized approaches to COS. For the majority of women undergoing COS and their treating physicians, the goal is to achieve a healthy live birth through IVF in a fresh cycle. Opinions on how COS strategy best leads to this common goal varies among centers as many clinicians base COS strategy not on evidence obtained through prospective randomized trials, but rather through observational studies and experience. Overall, when it comes to COS most clinicians recognize the approach should not be “one size fits all”, but rather a patient-centered approach that takes the existing evidence into consideration. The pages that follow outline the existing evidence for best practices in COS for IVF highlighting how these practices may be incorporated into a patient-centered approach.

Keywords: Controlled ovarian stimulation, gonadotropins, in vitro fertilization

Introduction

When the first live birth through IVF was achieved in 1978, it was through a natural cycle (Steptoe & Edwards, 1978). Inspired by this birth, Georgeanna and Howard Jones developed the first IVF program in the United States—the program for the Vital Initiation of Pregnancy (VIP) (Jones et al., 1982). In 1980, the program's first year of operation, the Joneses attempted laparoscopic oocyte retrieval in 41 women. Disappointingly, none of these procedures resulted in pregnancy. Reflecting on theirapproach, Georgeanna Jones decided moving forward the VIP program would use human menopausal gonadotropin to hyperstimulate the ovary and improve the efficiency of oocyte retrieval. At the end of 1981 this decision led to the birth of Elizabeth Carr, the first child born from IVF in the United States. She was born after her mother received a total of 7 ampules of human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) over 4 days. No more than 150 international units (IU) of hMG, or two ampules, were given per day. With this formula, Georgeanna and Howard Jones performed 55 laparoscopic oocyte retrievals resulting in 31 embryo transfers and 7 pregnancies over the course of one year (Jones, 2008).

The Jonses’ 7 ampule strategy was a minimalist approach by today's standards where on average 150-300 IU of gonadotropin is used daily for 9-10 days (Fritz, 2011; Van Voorhis, Thomas, Surrey, & Sparks, 2010). Compared to IVF in 1981, there are also a number of technological advances that have optimized the oocyte to embryo ratio and IVF embryo implantation rates (Beall & DeCherney, 2012). These advances have led some clinicians to advocate for minimal gonadotropin dosing in COS to decrease risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, reduce medication and monitoring costs, and to create a more “patient-friendly approach” to COS (Beall & DeCherney, 2012; Gianaroli et al., 2012; Lyerly et al., 2010; Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive & the Society for Assisted Reproductive, 2013; Verpoest et al., 2008). Furthermore, controversy exists as to whether or not increasing doses of gonadotropin in COS increase the risk of embryonic aneuploidy and adverse IVF outcome (Baart et al., 2007; Kovacs, Sajgo, Kaali, & Pal, 2012; Labarta et al., 2012; Verpoest et al., 2008). On the other hand, the overall time commitment and high costs associated with IVF, and the age-related decline in ovarian function have led others to consider COS strategies centered on obtaining a larger cohorts of oocytes available for both current and future use (Trounson & Mohr, 1983; Wong, Mastenbroek, & Repping, 2014). Such strategies are also advocated for women facing gonadotoxic treatment that may shorten the normal reproductive window (Jungheim, Carson, & Brown, 2010).

With improved understanding of reproductive biology, laboratory and pharmaceutic advances, and evolving strategies for family building through IVF, there is increasing attention on the importance of COS to IVF outcomes. The purpose of this review is to discuss the rationale and existing evidence for best practices in COS for IVF. More specifically we will address the optimal dosing of gonadotropins, the timing of gonadotropins, and adjuvants to gonadotropins in COS. We will also discuss some special clinical circumstances that may benefit from specific approaches in COS. Where the evidence is lacking we offer expert opinion on the issues incorporating personal and shared clinical experience.

General approaches to COS in IVF

Today, most stimulation protocols start with 150-300 IU of gonadotropin given daily with 225 IU being the standard starting dose for most patients (Fritz, 2011). Many clinicians use patient age and markers of ovarian reserve such as antral follicle counts (AFC), anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) levels, and/or early follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol levels to guide this starting dose (La Marca & Sunkara, 2014; Van Voorhis et al., 2010). For women suspected or proven to have poor ovarian reserve, a number of studies have demonstrated that doses higher than 450 IU per day do not result in higher oocyte yields or better pregnancy rates after IVF (Berkkanoglu & Ozgur, 2010; Fritz, 2011).

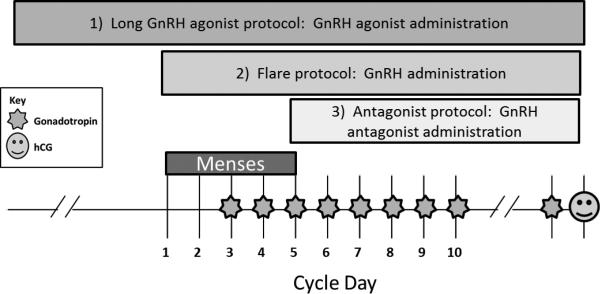

There are three basic COS protocols including the long agonist protocol, antagonist protocol, and the flare protocol. Different nomenclature is used for these protocols, but the basic components are the same. Components of these three protocols are illustrated in Figure 1. Table 1 outlines advantages to each protocol and data to support the use of specific protocols for certain diagnoses or clinical scenarios (Nardo, Bosch, Lambalk, & Gelbaya, 2013).

Figure 1.

COS protocols

Table 1.

advantages of specific protocols and clinical scenarios in which they may be preferred.

| Advantages | Specific scenarios/diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|

| Long agonist | • Flexibility in scheduling gonadotropin start | • Endometriosis |

| Antagonist | • Fewer shots and lower drug costs • Overall lower risk of OHSS • Ability to trigger with GnRH agonist to avoid OHSS |

• Women at risk for hyperresponse • Random/luteal phase start protocols for women undergoing emergent fertility preservation |

| Flare | • Poor responders |

In addition to choices for COS protocols, there is choices as to what type of gonadotropin formulation to use. There are highly purified urinary formulations of (follicle stimulating hormone) FSH and hMG, recombinant forms of FSH, and hCG available (Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 2008). In a recent meta-analysis of 42 trials involving 9606 women, no statistical difference was noted in live birth rate between recombinant FSH and any other gonadotropin regimen studied. The authors of the meta-analysis concluded that choice of gonadotropin should depend on availability, convenience and costs. In general, whether or not hMG or hCG should be included in COS to offer some LH activity is debated (Coomarasamy et al., 2008; Lehert, Schertz, & Ezcurra, 2010; van Wely et al., 2011; Wechowski, Connolly, Schneider, McEwan, & Kennedy, 2009). Regardless of this debate, there are clinical scenarios in which a gonadotropin with luteinizing hormone (LH) activity, either hMG or hCG, should never be omitted. These include cases of hypothalamic amenorrhea, and cases in which GnRH antagonists are used and LH levels are extremely suppressed (Propst et al., 2011; The European Recombinant Human LH Study, 1998). In regards to hCG formulations for triggering final follicular maturation, a recent Cochrane review demonstrated no difference in recombinant versus urinary hCG (Youssef, Al-Inany, Aboulghar, Mansour, & Abou-Setta, 2011).

Aside from choice of COS protocol, and gonadotropin formulation and dose, one must also choose how often to give gonadotropins in COS. The data as to whether single daily dosing versus split daily dosing of gonadotropin is conflicting with some studies suggesting split dosing yields better results (Awwad et al., 2013; Fox et al., 1996), others demonstrating that single daily dosing is better (Sharara, Collins, & Abdo, 2012), and other concluding there is no clinical difference (Dahan & Lathi, 2014). At the end of the day, this question will ultimately become irrelevant if corifollitropin alfa, a long acting injection of FSH given once at the beginning of COS, catches on. Initial studies demonstrate similar cumulative pregnancy rates compared to daily injections of recombinant FSH (Devroey et al., 2009) for lower costs (Boostanfar et al., 2012).

Packaging COS: the Nordstrom approach, the best-practice model, or “one size fits most”

Overall, as discussed in the previous section, studies investigating one COS protocol over another, one gonadotropin formulation over another and one dosing strategy over another are either inconclusive or not convincing. The differences in results of the studies addressing similar questions can likely be attributed to the lack of RCT study designs in COS, and the heterogeneity in populations studied. Given the time and cost required for RCTs, it is unlikely that such trials will be initiated. To address this, Van Voorhis and co-authors made the argument that a “best-practice” approach to IVF might be something to consider (Van Voorhis et al., 2010). They describe the best-practice model as one in which processes are identified and modeled from profitable and efficient practices, and implemented. In their model, Van Voorhis, et al, surveyed consistently high performing IVF programs in the United States to identify common practices. In regards to COS, they posed the following clinical scenario for a patient undergoing IVF:

A normal weight, 32-year-old woman with normal ovarian reserve and no history ovulatory dysfunction.

What they found in the survey responses was that the majority of the practices would do following:

Testing patients for ovarian reserve

Use a step-down approach to gonadotropin dosing

Use a protocol containing both FSH and LH

Recommend cycle cancellation with 3 or fewer mature follicles

Perform hCG trigger when two lead follicles were ≥ 18 mm or greater

While this knowledge is helpful, it is interesting to note that even with this approach few common practices to COS were identified in this survey. There were conflicting responses about how much gonadotropin practices would start with. There were also conflicting responses on whether once a day or twice a day dosing was preferred. The findings of this survey do not mean the details of COS are not important to IVF outcomes, but rather they suggest that there are a number COS strategies that may lead to success.

The boutique approach to COS: accessories

While the clinical scenario posed to high performing practices in the Van Voorhis paper is common, it is not representative of the tough cases in IVF that fall outside the “one size fits most” model. Such cases include poor responders, women with underlying endocrinopathies, or women undergoing COS-IVF for fertility preservation among other things. Whatever the case is, there are adjuvants that may be helpful in specific scenarios. Some of the more common scenarios for which a boutique approach may be called for are listed in table 2 along with adjuvants and data supporting their use (Azim, Costantini-Ferrando, & Oktay, 2008; Fiedler & Ezcurra, 2012; Leitao, Moroni, Seko, Nastri, & Martins, 2014; Mathur, Alexander, Yano, Trivax, & Azziz, 2008; Reynolds et al., 2013; Tso, Costello, Albuquerque, Andriolo, & Macedo, 2014; Youssef et al., 2014).

There are a number of other adjuvant treatments that have been recommended outside of what is listed in table 2 that are commonly used by practitioners. But, the use of these treatments is often based on basic science data rather than on evidence from well-conducted human studies. Such adjuvants include human growth hormone, Coenzyme Q10, dehydroepiandosterone, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, aspirin, and acupuncture. Based on the lack of data available supporting benefit for any these adjuvants, we do not advocate their use in unselected populations of women undergoing IVF (Bentov, Hannam, Jurisicova, Esfandiari, & Casper, 2014; Bromer, Cetinkaya, & Arici, 2008; Meldrum, Fisher, Butts, Su, & Sammel, 2013; Nardo, El-Toukhy, Stewart, Balen, & Potdar, 2014; Polanski et al., 2014).

Back to the future: is less gonadotropin best?

While some clinicians recommend adjuvants to COS in women who are poor responders, others may advocate for natural cycle IVF or minimal gonadotropin dosing during COS for IVF in poor responders. The rationale being that the number of oocytes retrieved from maximal stimulation in poor responders may be similar to the number of oocytes retrieved during a natural or minimally stimulated cycle. Beyond poor responders, in women who are expected to be normal responders, given the costs, the time commitment and complications associated with COS like OHSS, and the lack of data supporting the need for complex COS protocols, some have questioned whether natural cycle or COS with minimal stimulation would be more “patient-friendly” for the general population of women undergoing COS-IVF (Gianaroli et al., 2012).

A recent Cochrane review concluded that there is a lack of data to draw conclusions regarding the success of natural cycle IVF for infertile women compared to standard COS-IVF. Some smaller studies suggest that natural cycle IVF is associated with increased cancellation rates and lower chances of pregnancy (Allersma, Farquhar, & Cantineau, 2013; Fritz, 2011). On the other hand, supporting minimalist approaches to COS there is animal data demonstrating that COS may have a negative impact on embryonic development and increase the risk of chromosomal abnormalities (Allersma et al., 2013; Labarta et al., 2012; Sato, Otsu, Negishi, Utsunomiya, & Arima, 2007). The human data addressing this topic is sparse, but there is one study suggesting that gonadotropin stimulation may increase the risk of chromosomal abnormalities in a dose-dependent manner (Baart et al., 2007). However, in 2008 it was reported that even in unstimulated cycles 36.4% of embryos were aneuploid (Verpoest et al., 2008). Similar aneuploid results were found among embryos obtained from unstimulated cycles in a publication by Labarta, et al. published in 2010. In this study, the authors prospectively compared aneuploid rates in embryos obtained from stimulated cycles to those of embryos obtained from unstimulated cycles in the same women. They found no statistical difference (risk difference 3.4, 95% CI: −17.9-11.2, 34.8% versus 38.2%, p=0.64).

Aside from the controversy and inconclusive studies on the risk COS may pose to embryos, there is also concern that COS poses harm to the endometrium thus impacting implantation during fresh embryo transfer (Kovacs et al., 2012). On the other hand, some IVF practices advocate for freeze-all approaches with subsequent frozen embryo transfer to avoid the supraphysiologic environment that COS poses and the risk of OHSS (Barnhart, 2014). With vitrification of embryos being so successful in many practices this is not an unreasonable consideration (Wong et al., 2014). Furthermore the approach of trying to maximize cumulative pregnancy rate from one cycle may be ideal for women with goals for fertility preservation, women who will require ART for all future pregnancies, and for women who want to maximize cost-effectiveness for IVF-related family building. Such a strategy may increase OHSS risk, but with expanding options for avoiding OHSS many clinicians and patients alike may prefer this strategy. These options include coasting, early trigger, GnRH trigger, lower hCG dosing for trigger, adjuvant cabergoline therapy, and freeze all protocols with frozen embryo transfer at a later date (Fiedler & Ezcurra, 2012).

There is a trial currently underway in the Netherlands investigating the cost-effectiveness of FSH stimulation dosages for IVF treatment (van Tilborg et al., 2012). How generalizable the results of this trial will be to the United States is hard to know, but nevertheless the results may be helpful in guiding COS treatment strategies and guiding discussions with patients.

Individualizing the approach: making the case for shared decision making and patient centered care in COS

A recent joint statement from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology discusses “patient-tailored stimulation”. This patient-tailored approach should likely be the result of a shared decision making (SDM) process. In a recent review by psychologist and communications expert, Dr. Mary Politi, SDM is advocated for situations where decisions are being made between treatment options with “similar outcomes from a medical standpoint” where “patients’ preferences for the possible risks, benefits, and trade-offs between options are central to the decision” (Politi, Lewis, & Frosch, 2013).

While the bulk of the existing data addressing the question of COS-IVF is aimed at general cohorts of patients, as discussed there are often specific considerations that need to be taken into account. Furthermore, in embarking on family building, many women and their partners want and often expect an individualized approach. In her review, Politi explains that to engage in SDM, clinicians must explain the decision to be made, the options that are available, elicit the patients’ preferences about outcomes, and work to establish a treatment plan. This is certainly something we all strive for in everyday practice, but tools that help in the process like decision aids may be helpful in engaging patients in this process. Decision aids have been created to assist patients decide how many embryos to transfer, but to date no such aid exists for determining the approach to COS (van Peperstraten et al., 2010).

Conclusions

Based on the data outlined in the preceding work it is clear that there are many paths to achieving successful COS in IVF. Best practices for most women undergoing COS-IVF likely incorporate 150-300 IU of gonadotropins daily but no more than 450 IU a day. How to pick the dose is often guided by patient age and some marker of ovarian reserve with 150 IU being reserved for women who are younger and expected to have a robust response and higher doses being used in women who are older or who are expected to have a poorer response. Much of the other data on choices in COS is either not convincing or it is inconclusive. Aside from a narrow range of daily gonadotropin dosing in COS, the approach to COS should likely be patient-centered, informed by clinical experience, and by a critical and continuous appraisal of the published data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

ESJ receives support from the Women's Reproductive Health Research Program sponsored by the National Institute of Health (K12 HD063086), the Institute of Clinical and Translational Studies at Washington University and the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation (UL1 TR000448), and the March of Dimes.

Contributor Information

Emily S. Jungheim, Washington University School of Medicine, 4444 Forest Park Ave., Ste. 3100, St. Louis, MO 63108.

Melissa Meyer, Washington University School of Medicine, meyerme@wusm.wudosis.edu.

Darcy E. Broughton, Oregon Health and Science University, broughtond@ohsu.edu.

References

- Allersma T, Farquhar C, Cantineau AE. Natural cycle in vitro fertilisation (IVF) for subfertile couples. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD010550. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010550.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010550.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awwad JT, Farra C, Mitri F, Abdallah MA, Jaoudeh MA, Ghazeeri G. Split daily recombinant human LH dose in hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism: a nonrandomized controlled pilot study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;26(1):88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.09.016. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim AA, Costantini-Ferrando M, Oktay K. Safety of fertility preservation by ovarian stimulation with letrozole and gonadotropins in patients with breast cancer: a prospective controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2630–2635. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baart EB, Martini E, Eijkemans MJ, Van Opstal D, Beckers NG, Verhoeff A, Fauser BC. Milder ovarian stimulation for in-vitro fertilization reduces aneuploidy in the human preimplantation embryo: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(4):980–988. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del484. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart KT. Introduction: are we ready to eliminate the transfer of fresh embryos in in vitro fertilization? Fertil Steril. 2014;102(1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.024. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall SA, DeCherney A. History and challenges surrounding ovarian stimulation in the treatment of infertility. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(4):795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.030. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentov Y, Hannam T, Jurisicova A, Esfandiari N, Casper RF. Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation and Oocyte Aneuploidy in Women Undergoing IVF-ICSI Treatment. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health. 2014;8:31–36. doi: 10.4137/CMRH.S14681. doi: 10.4137/CMRH.S14681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkkanoglu M, Ozgur K. What is the optimum maximal gonadotropin dosage used in microdose flare-up cycles in poor responders? Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):662–665. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.027. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boostanfar R, Mannaerts B, Pang S, Fernandez-Sanchez M, Witjes H, Devroey P, Engage I. A comparison of live birth rates and cumulative ongoing pregnancy rates between Europe and North America after ovarian stimulation with corifollitropin alfa or recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(6):1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.038. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromer JG, Cetinkaya MB, Arici A. Pretreatments before the induction of ovulation in assisted reproduction technologies: evidence-based medicine in 2007. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1127:31–40. doi: 10.1196/annals.1434.004. doi: 10.1196/annals.1434.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coomarasamy A, Afnan M, Cheema D, van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM, van Wely M. Urinary hMG versus recombinant FSH for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation following an agonist long down-regulation protocol in IVF or ICSI treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(2):310–315. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem305. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan MH, Lathi RB. Twice-daily dosing of gonadotropins does not improve embryo quality during in vitro fertilization cycles in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, when compared to once-daily dosing: a pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289(5):1113–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3095-2. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devroey P, Boostanfar R, Koper NP, Mannaerts BM, Ijzerman-Boon PC, Fauser BC, Investigators E. A double-blind, non-inferiority RCT comparing corifollitropin alfa and recombinant FSH during the first seven days of ovarian stimulation using a GnRH antagonist protocol. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3063–3072. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep291. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K, Ezcurra D. Predicting and preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): the need for individualized not standardized treatment. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JH, Jackson KV, Rein MS, Hornstein MD, Clarke RN, Friedman AJ. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the clinical effects of split-versus single-dose human menopausal gonadotropins in an assisted reproductive technology program. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(3):598–602. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)58161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MA. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 8th ed. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gianaroli L, Racowsky C, Geraedts J, Cedars M, Makrigiannakis A, Lobo RA. Best practices of ASRM and ESHRE: a journey through reproductive medicine. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(6):1380–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1164. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HW., Jr. The use of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) in clinical in vitro fertilization: the role of Georgeanna Seegar Jones. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5):e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1333. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HW, Jr., Jones GS, Andrews MC, Acosta A, Bundren C, Garcia J, Wright G. The program for in vitro fertilization at Norfolk. Fertil Steril. 1982;38(1):14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungheim ES, Carson KR, Brown D. Counseling and consenting women with cancer on their oncofertility options: a clinical perspective. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;156:403–412. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6518-9_31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6518-9_31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs P, Sajgo A, Kaali SG, Pal L. Detrimental effects of high-dose gonadotropin on outcome of IVF: making a case for gentle ovarian stimulation strategies. Reprod Sci. 2012;19(7):718–724. doi: 10.1177/1933719111432859. doi: 10.1177/1933719111432859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Marca A, Sunkara SK. Individualization of controlled ovarian stimulation in IVF using ovarian reserve markers: from theory to practice. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(1):124–140. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt037. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarta E, Bosch E, Alama P, Rubio C, Rodrigo L, Pellicer A. Moderate ovarian stimulation does not increase the incidence of human embryo chromosomal abnormalities in in vitro fertilization cycles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(10):E1987–1994. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1738. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehert P, Schertz JC, Ezcurra D. Recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone produces more oocytes with a lower total dose per cycle in assisted reproductive technologies compared with highly purified human menopausal gonadotrophin: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:112. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-112. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao VM, Moroni RM, Seko LM, Nastri CO, Martins WP. Cabergoline for the prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):664–675. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.005. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly AD, Steinhauser K, Voils C, Namey E, Alexander C, Bankowski B, Wallach E. Fertility patients' views about frozen embryo disposition: results of a multi-institutional U.S. survey. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(2):499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.015. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur R, Alexander CJ, Yano J, Trivax B, Azziz R. Use of metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):596–609. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.010. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum DR, Fisher AR, Butts SF, Su HI, Sammel MD. Acupuncture--help, harm, or placebo? Fertil Steril. 2013;99(7):1821–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.046. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardo LG, Bosch E, Lambalk CB, Gelbaya TA. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation regimens: a review of the available evidence for clinical practice. Produced on behalf of the BFS Policy and Practice Committee. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2013;16(3):144–150. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2013.795385. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2013.795385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardo LG, El-Toukhy T, Stewart J, Balen AH, Potdar N. British Fertility Society Policy and Practice Committee: Adjuvants in IVF: Evidence for good clinical practice. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2014:1–14. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2015.985454. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2015.985454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanski LT, Barbosa MA, Martins WP, Baumgarten MN, Campbell B, Brosens J, Raine-Fenning N. Interventions to improve reproductive outcomes in women with elevated natural killer cells undergoing assisted reproduction techniques: a systematic review of literature. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(1):65–75. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det414. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi MC, Lewis CL, Frosch DL. Supporting shared decisions when clinical evidence is low. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(1 Suppl):113S–128S. doi: 10.1177/1077558712458456. doi: 10.1177/1077558712458456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine, B. A. Gonadotropin preparations: past, present, and future perspectives. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5 Suppl):S13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.031. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive, M., & the Society for Assisted Reproductive, T. In vitro maturation: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(3):663–666. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.031. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propst AM, Hill MJ, Bates GW, Palumbo M, Van Horne AK, Retzloff MG. Low-dose human chorionic gonadotropin may improve in vitro fertilization cycle outcomes in patients with low luteinizing hormone levels after gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist administration. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(4):898–904. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.069. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds KA, Omurtag KR, Jimenez PT, Rhee JS, Tuuli MG, Jungheim ES. Cycle cancellation and pregnancy after luteal estradiol priming in women defined as poor responders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(11):2981–2989. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det306. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Otsu E, Negishi H, Utsunomiya T, Arima T. Aberrant DNA methylation of imprinted loci in superovulated oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):26–35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del316. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharara FI, Collins MG, Abdo G. Decreased gonadotropin requirements in once daily compared to twice daily administration: a prospective, randomized study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(4):321–324. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9713-2. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9713-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe PC, Edwards RG. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet. 1978;2(8085):366. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The European Recombinant Human LH Study, G. Recombinant human luteinizing hormone (LH) to support recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)-induced follicular development in LH- and FSH-deficient anovulatory women: a dose-finding study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(5):1507–1514. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4770. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trounson A, Mohr L. Human pregnancy following cryopreservation, thawing and transfer of an eight-cell embryo. Nature. 1983;305(5936):707–709. doi: 10.1038/305707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso LO, Costello MF, Albuquerque LE, Andriolo RB, Macedo CR. Metformin treatment before and during IVF or ICSI in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;11:CD006105. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006105.pub3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006105.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Peperstraten AM, Hermens RP, Nelen WL, Stalmeier PF, Wetzels AM, Maas PH, Grol RP. Deciding how many embryos to transfer after in vitro fertilisation: development and pilot test of a decision aid. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(1):124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.007. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tilborg TC, Eijkemans MJ, Laven JS, Koks CA, de Bruin JP, Scheffer GJ, Broekmans FJ. The OPTIMIST study: optimisation of cost effectiveness through individualised FSH stimulation dosages for IVF treatment. A randomised controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. 2012;12:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-12-29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-12-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhis BJ, Thomas M, Surrey ES, Sparks A. What do consistently high-performing in vitro fertilization programs in the U.S. do? Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4):1346–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.048. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wely M, Kwan I, Burt AL, Thomas J, Vail A, Van der Veen F, Al-Inany HG. Recombinant versus urinary gonadotrophin for ovarian stimulation in assisted reproductive technology cycles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD005354. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005354.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005354.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verpoest W, Fauser BC, Papanikolaou E, Staessen C, Van Landuyt L, Donoso P, Devroey P. Chromosomal aneuploidy in embryos conceived with unstimulated cycle IVF. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(10):2369–2371. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den269. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechowski J, Connolly M, Schneider D, McEwan P, Kennedy R. Cost-saving treatment strategies in in vitro fertilization: a combined economic evaluation of two large randomized clinical trials comparing highly purified human menopausal gonadotropin and recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone alpha. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.034. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KM, Mastenbroek S, Repping S. Cryopreservation of human embryos and its contribution to in vitro fertilization success rates. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.027. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef MA, Al-Inany HG, Aboulghar M, Mansour R, Abou-Setta AM. Recombinant versus urinary human chorionic gonadotrophin for final oocyte maturation triggering in IVF and ICSI cycles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(4):CD003719. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003719.pub3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003719.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef MA, Van der Veen F, Al-Inany HG, Mochtar MH, Griesinger G, Nagi Mohesen M, van Wely M. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist versus HCG for oocyte triggering in antagonist-assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD008046. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008046.pub4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008046.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.