Abstract

Brucella is a facultative intracellular bacterium belongs to the class alpha proteobacteria. It causes zoonotic disease brucellosis to wide range of animals. Brucella species are highly conserved in nucleotide level. Here, we employed a comparative genomics approach to examine the role of homologous recombination and positive selection in the evolution of Brucella. For the analysis, we have selected 19 complete genomes from 8 species of Brucella. Among the 1599 core genome predicted, 24 genes were showing signals of recombination but no significant breakpoint was found. The analysis revealed that recombination events are less frequent and the impact of recombination occurred is negligible on the evolution of Brucella. This leads to the view that Brucella is clonally evolved. On other hand, 56 genes (3.5 % of core genome) were showing signals of positive selection. Results suggest that natural selection plays an important role in the evolution of Brucella. Some of the genes that are responsible for the pathogenesis of Brucella were found positively selected, presumably due to their role in avoidance of the host immune system.

Keywords: Brucella, Recombination, Positive selection, Evolution

Introduction

Homologous recombination and positive selection are considered as indispensable driving forces that play a major role in the evolution of microorganisms. The importance of recombination and positive selection in the molecular evolution of bacterial pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes [1], E. coli [2], Streptococcus [3] have been reported earlier. Positive selection is often characterised by estimating the ratio (ω) of nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitutions [4]. This ratio provides measure of natural selection with ω = 1, <1, >1 indicating neutral evolution, purifying selection (negative selection) and positive selection, respectively. The identification of positively selected genes in the core genome of an organism will reveal the evolutionary path of that organism. The gene products which have significant role in bacterial pathogenesis are more likely to be positively selected.

Brucella is an important zoonotic pathogen that causes brucellosis. It has a wide host range, infecting from domestic animals to rodents, cetaceans and humans. The genus Brucella is classified into ten species based on host specificity: Brucella melitensis (goats), Brucella abortus (cattle), Brucella suis (swine), Brucella canis (dogs), Brucella ovis (sheep), Brucella neotomae (desert mice), Brucella ceti (cetacean), Brucella pinnipedialis (seal), Brucella microti (voles) and Brucella inopinata (unknown) [5]. Brucellosis induces abortion in animals and causes undulant fever, endocarditis, osteoarthritis and several neurological disorders in humans [6]. Brucella melitensis, B. suis and B. abortus are known to cause human brucellosis [6]. Brucella is a facultative intracellular pathogen which survives and replicates in the host macrophages. It lacks classical bacterial virulence factors such as fimbria, exotoxins, capsules, plasmids etc. Virulence factors such as lipopolysaccharide, type IV secretion system, and BvrR/BvrS two-component system have been identified to be critical in the intracellular process of Brucella inside macrophages [7].

Since the Brucella species are highly conserved in nucleotide level, we have employed a genome wide analysis to assess the effect of homologous recombination and positive selection in the core genome of 19 Brucella genomes to analyse the evolutionary nature of this pathogenic bacteria.

Materials and Methods

Genome Sequences

We have considered complete genomes of Brucella available in NCBI as of November 1, 2014. Genome sequences of 19 complete genomes of Brucella (Table 1) were retrieved from NCBI database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/).

Table 1.

Genomes used in this study

| Genome | Genome status | Genbank accession | Refseq accession | Genome length (bp) | GC content (%) | CDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brucella abortus A13334 | Complete |

CP003176 CP003177 |

NC_016777 NC_016795 |

3,286,032 | 57.2 | 3338 |

| Brucella abortus S19 | Complete |

CP000887 CP000888 |

NC_010742 NC_010740 |

3,283,936 | 57.2 | 3000 |

| Brucella abortus 2308 | Complete |

AM040264 AM040265 |

NC_007618 NC_007624 |

3,278,307 | 57.2 | 3034 |

| Brucella abortus bv. 1 str. 9-941 | Complete |

AE017223 AE017224 |

NC_006932 NC_006933 |

3,286,445 | 57.2 | 3085 |

| Brucella canis HSK A52141 | Complete |

CP003174 CP003175 |

NC_016778 NC_016796 |

3,277,512 | 57.2 | 3280 |

| Brucella canis ATCC 23365 | Complete |

CP000872 CP000873 |

NC_010103 NC_010104 |

3,312,769 | 57.2 | 3251 |

| Brucella melitensis bv. 1 str. 16 M | Complete |

AE008917 AE008918 |

NC_003317 NC_003318 |

3,294,931 | 57.2 | 3198 |

| Brucella melitensis ATCC 23457 | Complete |

CP001488 CP001489 |

NC_012441 NC_012442 |

3,311,219 | 57.2 | 3136 |

| Brucella melitensis M5-90 | Complete |

CP001851 CP001852 |

NC_017246 NC_017247 |

3,312,229 | 57.2 | 3360 |

| Brucella melitensis NI | Complete |

CP002931 CP002932 |

NC_017248 NC_017283 |

3,294,475 | 57.2 | 3229 |

| Brucella melitensis M28 | Complete |

CP002459 CP002460 |

NC_017244 NC_017245 |

3,311,748 | 57.2 | 3363 |

| Brucella suis ATCC 23445 | Complete |

CP000911 CP000912 |

NC_010169 NC_010167 |

3,324,607 | 57.2 | 3241 |

| Brucella suis 1330 | Complete |

AE014291 AE014292 |

NC_004310 NC_004311 |

3,315,175 | 57.3 | 3272 |

| Brucella suis VBI22 | Complete |

CP003128 CP003129 |

NC_016775 NC_016797 |

3,316,088 | 57.2 | 3270 |

| Brucella microti CCM 4915 | Complete |

CP001578 CP001579 |

NC_013119 NC_013118 |

3,337,369 | 57.3 | 3282 |

| Brucella ceti TE10759-12 | Complete |

CP006897 CP006896 |

NC_022906 NC_022905 |

3,278,034 | 57.2 | 2611 |

| Brucella ceti TE28753-12 | Complete |

CP006899 CP006898 |

NC_022908 NC_022907 |

3,277,545 | 57.1708 | 2376 |

| Brucella pinnipedialis B2/94 | Complete |

CP002078 CP002079 |

NC_015857 NC_015858 |

3,399,270 | 57.2 | 3325 |

| Brucella ovis ATCC 25840 | Complete |

CP000709 CP000708 |

NC_009504 NC_009505 |

3,275,590 | 57.2 | 2890 |

Recombination Analysis

We have tested the recombination events in the core genome (genes present in all genomes analysed) of Brucella using PSP server [8] (http://db-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/PSP/). The PSP server identified the core genome by detecting orthologous groups across multiple prokaryotic genomes being compared using OrthoMCL. Then it checked for recombination events through four statistical procedures GENECONV, pairwise homoplasy index (PHI), maximum χ2 and neighbor similarity score (NSS).

Effect of Recombination on Brucella Evolution

ClonalFrame [9] version 1.2 was applied to the 19 complete genomes of Brucella to identify the impact of recombination in the evolution of bacteria. Whole genome sequence alignment of 19 genomes was done using progressive Mauve [10] and the core genome alignment, where all genomes aligned over at least 500 bp was extracted using stripSubsetLCBs script distributed with Mauve. This core genome alignment was given as input for ClonalFrame to reconstruct the clonal relationship between the genomes. Separate alignments were made for Chromosome 1 and Chromosome 2. Four independent runs, each consisting of 20,000 MCMC iterations, in which the first half of the iterations were discarded as burn-in, were performed for chromosome 1 and 2. Convergence and mixing of MCMC runs were found to be satisfactory based on Gelman-Rubin test [11] using ClonalFrame genealogy comparison tool. The clonal genealogy obtained from ClonalFrame was used for the recombination analysis.

Positive Selection Analysis

PSP server was used for the identification of genes under positive selection in Brucella core genome. Codon-based strategy was used by PSP for the identification of orthologous coding genes under positive selection. We have used site models which will screen for presence of positively selected sites by allowing the dN/dS ratio (ω) to vary among sites. The null model M7 (beta), which assumes a beta distribution for ω (0 < x < 1) is compared with the alternative model M8 (beta & ω), which adds an extra class of sites with positive selection (ωs > 1). If the likelihood ratio test is significant, positive selection is inferred [4].

Results and Discussion

Recombination and positive selection is considered to be the major evolutionary forces behind the evolution of microorganisms. Previous studies revealed that Brucella is highly conserved in nucleotide level with nearly identical genetic content and gene organization [12]. Considering the conserved nature of Brucella, we assessed the role of recombination and positive selection in Brucella evolution.

Recombination had no Impact on the Evolution of Brucella

Among the 1599 core genome tested, only 24 genes were showing signals of recombination. No significant breakpoint was observed in any of these genes which show less impact of recombination in Brucella. To quantify and analyze the impact of recombination on Brucella, we applied ClonalFrame algorithm to the whole genome sequences of Brucella. The frequency of recombination is often measured relative to that of mutation. ClonalFrame measures the frequency of occurrence of recombination relative to mutation by estimating the ρ/θ value. A single event of recombination can change several nucleotides. ClonalFrame measures the effect of recombination by estimating r/m value which will measure the rates at which sites are altered through recombination and mutation. ρ/θ measured how often recombination events happened relative to mutation and r/m measured how important the effect of recombination was in the diversification of the bacterial species relative to mutation.

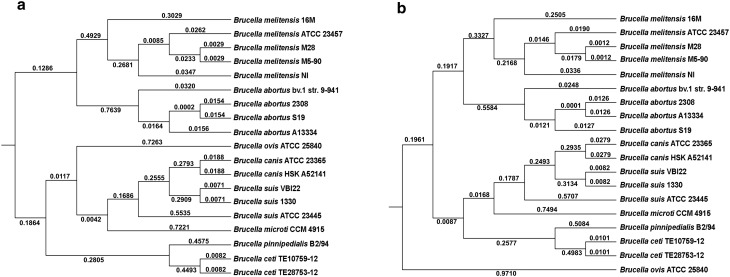

The whole genome alignment was performed and the core genome alignment was extracted as mentioned earlier. This resulted in 231 blocks with a total alignment length of 1,819,788 bp in chromosome 1 and 176 blocks with 1,013,561 bp alignment length in chromosome 2. These core regions were given as input to ClonalFrame. The tree topology obtained from ClonalFrame clearly depicts the clonal genealogy of Brucella (Fig. 1a, b). The tree separates Brucella into four different clades. B. melitensis clade, B. abortus clade, B. suis- B. canis-B. ovis-B. microti clade and the marine environmental species B. ceti and B. pinnipedialis clade. The clonal tree is in congruence with the whole genome based phylogenetic tree obtained in the previous study [13]. Earlier reports suggested that phylogenetic analysis of Brucella using 16S rDNA genes and MLST were not able to clearly depict the phylogeny of genus Brucella [13, 14]. The clonal genealogy obtained here was further used for recombination analysis. ClonalFrame estimated that recombination is very less frequent in Brucella with a ρ/θ = 0.0145 (with 95 % credibility interval of 0.0143 to 0.0147) in chromosome 1 and ρ/θ = 0.016 in chromosome 2 (with 95 % credibility interval of 0.012 to 0.019). The r/m value for chromosome 1 and chromosome 2 was estimated to be 0.096 (with 95 % credibility interval of 0.094 to 0.097) and 0.081(with 95 % credibility interval of 0.06 to 0.10) respectively. The ClonalFrame analysis (low rate of ρ/θ and r/m) shows that recombination events are very less frequent than mutation in Brucella and also the effect of recombination is very limited. The recombination analysis suggests that Brucella has evolved clonally. Clonal evolution or clonality refers to the evolution of a population structure that results from limited or absence of genetic recombination [15]. This refers to limited recombination, not the complete absence of recombination. If recombination cannot change or break the clonal population structure, then the organism is known to be clonally evolved. This pattern is widely accepted in the population structure of many pathogenic bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis [16], Salmonella typhi [17], Staphylococcus aureus [18] etc. In contrast, recombination played an important role in the genetic diversity of Listeria [1], Helicobacter pylori [19] etc. The effect of recombination in other rhizobiales such as Bartonella and Rhizobium is also minimal [20, 21]. The results we obtained indicate that recombination has had negligible impact on the diversification of the Brucella. The analysis suggests that the vast majority of clonal variants arise by point mutation, rather than recombination.

Fig. 1.

Clonal genealogy of Brucella (a) Chromosome I (b) Chromosome II. Phylogenetic tree generated by ClonalFrame using the core genome of Brucella chromosome I and chromosome II extracted from whole genome alignment

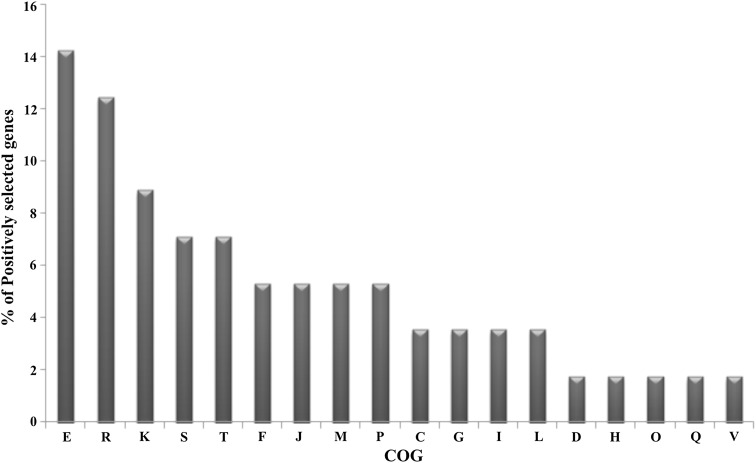

Genes Showing Evidence of Positive Selection

To identify genes under positive selection, we performed a genome-wide molecular selection analysis using PSP server for 19 complete genomes of Brucella in NCBI genome database. The average number of CDS in Brucella genomes was ~ 3300. Positive selection was done using the PAML software implemented in PSP. The analysis was carried out for the predicted 1599 orthologous groups in the core genome. Based on LRT statistics for comparing the null model and alternative model with χ2 distribution and correction for multiple testing (default value was used as mentioned in PSP server), we have identified 56 genes in the core group showing signals of positive selection in Brucella genomes with Pvalue < 0.05 and dn/ds > 1 (Table 2). Earlier Kim et al. [22] have reported that 12 genes of Brucella were positively selected by analysing seven complete genomes. Of these, nine genes were found to be positively selected in our study also. In this study, we did an extensive genome wide analysis in 19 genomes to identify genes under positive selection. Based on the criteria we used, our study identified more number of genes showing signals of positive selection compared to the previous report [22]. We identified an acid resistance gene, hdeA, showing strong signal of selection. The gene encoding acetyltransferase, hypothetical protein, med encoding basic membrane lipoprotein and ubiquinol oxidase, cyoA also showed strong signals of selection after hdeA. In addition to these genes, we identified some of the virulence genes, transporter genes, transcriptional regulators, genes in the two component system (phoR/phoB) etc. are positively selected. To get more insights into the evolutionary pressures acting on these Brucella genomes, we analysed the functional features of the positively selected genes. The positively selected genes are highly enriched in five COGs (E—amino acid transport and metabolism, R—general functional prediction only, K—transcription, S—function-unassigned conserved proteins, T—signal transduction) (Fig. 2; Table 2).

Table 2.

Genes under positive selection in the core genome of Brucella

| Gene | P value | dn/ds | COG | Gene products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hdeA | 0 | 117.43 | – | Acid resistance protein |

| – | 0 | 110.19 | – | Acetyltransferase |

| cog3319 | 0 | 79.47 | Q | Hypothetical protein |

| med | 0 | 64.52 | R | Basic membrane lipoprotein |

| cyoA | 0 | 33.00 | C | Ubiquinol oxidase, subunit II |

| putA | 0 | 18.00 | C | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family protein |

| dedA | 0 | 12.78 | S | Putative membrane-associated alkaline phosphatase |

| agaS | 0.0468 | 12.13 | M | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase |

| cog3324 | 0 | 5.48 | R | Glyoxalase, putative |

| hsdS | 0 | 5.28 | V | Type I restriction enzyme EcoR124II specificity protein |

| hisJ | 0 | 5.13 | ET | Amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic amino acid-binding protein |

| malK | 0 | 4.82 | G | Sugar ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| rplD | 0 | 4.76 | J | 50S ribosomal protein L4 |

| queA | 0.0436 | 4.31 | J | S-adenosylmethionine:tRNA ribosyltransferase-isomerase |

| cysZ | 0 | 4.13 | E | CysZ-like protein |

| mviM | 0 | 3.30 | R | Glucose-fructose oxidoreductase precursor |

| caiA | 0 | 3.07 | I | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| cysU | 0 | 3.05 | O | Sulfate transport system permease protein |

| repB | 0 | 2.99 | K | Replication protein |

| crp | 0.0067 | 2.92 | T | Crp/FNR family transcriptional regulator |

| nlpA | 0 | 2.81 | P | Lipoprotein, yaeC family |

| thrB | 0 | 2.70 | R | Homoserine kinase |

| iclR | 0 | 2.44 | K | Transcriptional regulator |

| cysI | 0 | 2.35 | P | Sulfite reductase (NADPH) hemoprotein beta-component |

| – | 0.0046 | 2.29 | – | Hypothetical protein |

| – | 0 | 2.26 | – | Hypothetical protein |

| hipB | 0 | 2.23 | K | Hypothetical protein |

| queD | 0.0025 | 2.23 | H | Queuosine biosynthesis protein |

| carB | 0 | 2.16 | EF | Carbamoyl phosphate synthase large subunit |

| ureB | 0.0067 | 2.08 | E | Urease subunit beta |

| phoR | 0 | 2.06 | T | Phosphate regulon sensor protein |

| hisM | 0 | 2.03 | E | Amino acid ABC transporter, permease protein |

| thiP | 0 | 1.97 | P | Iron compound ABC transporter permease |

| tgt | 0 | 1.96 | J | Queuine tRNA-ribosyltransferase |

| cog2845 | 0 | 1.82 | S | Hypothetical protein |

| cog3845 | 0 | 1.73 | R | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| ugpE | 0 | 1.69 | G | Sugar ABC transporter, permease protein, putative |

| gumC | 0 | 1.68 | M | Exopolysaccharide biosynthesis protein Bme12 |

| cog5426 | 0.0184 | 1.68 | S | Hypothetical protein |

| arnT | 0 | 1.66 | M | Dolichyl-phosphate-mannose-protein mannosyltransferase family protein |

| cog3346 | 0.0106 | 1.64 | S | SurF1 family protein |

| oxyR | 0.0311 | 1.63 | K | Transcriptional regulator |

| cog2378 | 0 | 1.61 | K | Hypothetical protein |

| cog0436 | 0 | 1.51 | E | Aminotransferase, class I |

| xthA | 0.0046 | 1.50 | L | Exodeoxyribonuclease III |

| pyrF | 0.0086 | 1.44 | F | Orotidine 5-phosphate decarboxylase |

| guaA | 0 | 1.43 | F | GMP synthase |

| cog1123 | 0.0046 | 1.41 | R | Peptide ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein |

| speB | 0 | 1.39 | E | Agmatinase |

| mviN | 0 | 1.33 | R | Virulence factor |

| cog1054 | 0 | 1.32 | R | Rhodanese family protein |

| nikC | 0 | 1.12 | EP | Nickel transporter permease |

| ftsZ | 0 | 1.24 | D | Cell division protein |

| cog3436 | 0 | 1.22 | L | IS66 family element, orf3 |

| cdsA | 0 | 1.08 | I | Phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase |

| phoH | 0.0165 | 1.06 | T | Hypothetical protein |

Fig. 2.

COG classification of genes under positive selection in Brucella genomes. Percent representation was calculated as number of positively selected genes involved in a given COG/number of all genes under positive selection. The COGs categories are coded as follows: E, amino acid transport and metabolism; R, general functional prediction only; K, transcription; S, function-unassigned conserved proteins; T, signal transduction; F, nucleotide transport and metabolism; J, translation; M, cell wall/membrane biogenesis; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; C, energy production and conversion; G, carbohydrate transport and metabolism; I, lipid metabolism; L, DNA replication, recombination and repair; D, cell division and chromosome partitioning; H, coenzyme metabolism; O, posttranslational modification, protein turnover and chaperones; Q, secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism; V, defence mechanisms

The ability of Brucella to survive in the environmental conditions such as acidic pH, low levels of nutrients, and reactive oxygen intermediates accounts for its virulence and pathogenicity. During the bacterial infection, the host develops certain defence mechanisms such as acidification of pathogen containing phagosomes, oxygen radical generation, phagosome–lysosome fusion etc. to eliminate the bacteria. To counteract such defence responses from host, intracellular bacteria have developed various resistance mechanisms. Some of the genes that could play important roles in such resistance mechanisms and pathogenesis of Brucella were identified as positively selected genes.

hdeA, an acid resistance protein showed strong signal of selection with higher ω value of 117.43. hdeA has been shown to be required for resisting acid shock in Brucella [23]. Since Brucella has to encounter the acidic stress incorporate by host immune system, acid resistance of pathogens are crucial. This gene may be positively selected to avoid host immune response. Blastn analysis of hdeA gene of Brucella showed 68 % similarity with Methylobacterium populi BJ001 strain, an alpha proteobacetria of order rhizobiales which was isolated from poplar trees. hdeA gene also showed 70 % homology with different E. coli strains and S. flexneri and S. sonnei.ureB is another important gene which plays vital role in acid resistance of Brucella. ureB, a component of urease which triggers ureolysis also found to be positively selected with an ω value of 2.0824. Ureolysis results in the release of ammonia molecules which will be protonated to form ammonium resulting in the increase of pH and thereby it protects the bacteria from lethal acidification. Urease is known to protect Brucella during their passage through the stomach when the bacteria are acquired by the oral route, which is the major route of infection in human brucellosis [24]. The mviN is a virulence factor family found in all Brucella species and also in the closest neighbour of Brucella,Ochrobactrum. This membrane bound protein shows similarity with Salmonella. The gene mviN of Brucella involves in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. The role of this gene in Brucella virulence is not well studied. xthA is known to protect the Brucella from oxidative damage and plays a major role in the base excision repair of bacterial DNA [25]. However, it is not required for virulence in a mouse model. Our study suggests that selection pressure acting on these genes to avoid the host stress response during the intracellular life of Brucella.

The gene encoding acetyltransferase was showing a strong signal of selection next to hdeA with an ω value of 110.191. In Brucella, acetyltransferase involved in tyrosine metabolism pathway, benzoate degradation pathway, ethylbenzene degradation pathway and limonene and pinene degradation pathway was also found to be positively selected. Blastn analysis of Brucella acetyltranferase revealed an ortholog in closest neighbour of Brucella, Ochrobactrum. med, a basic membrane lipoprotein which plays a role in the sugar transport system was also identified to be positively selected with an ω value of 64.523. The blastn analysis of med revealed 80 % similarity with Ochrobactrum, 72 % similarity with Roseobacter litoralis, a member of order Rhodobacterales of alpha proteobacteria, 71 % similarity with Agrobacteriumradiobacter and 75 % similarity with Sinorhizobiumfredii which belong to the order Rhizobiales of alpha proteobacteria. We identified cyoA which has its role in the oxidative phosphorylation to be positive selected with an ω value of 33.003. It showed similarity with Ochrobactrum and different strains of Pseudomonas.

Adaptive response of bacterium is usually directed by transcriptional factors and two-component regulatory systems [26]. We identified three transcriptional regulators, oxyR, crp/FNR family transcriptional regulator and iclR family transcriptional regulator and to be positively selected. The oxyR is also known to regulate the catalase activity, which plays a major role in the life of intracellular pathogens [27]. Phosphate regulator gene phoR was identified to be under positive selection in Brucella with an ω value of 2.065. The phoR codes for membrane kinase that regulates the transcriptional regulator, phoB. The phoR/phoB two component system controls the phosphate uptake and regulate large number of genes including nine transcriptional regulators including phoH, which is also positively selected in Brucella.

ABC transporters play a major role in the export and import of many different substances across cellular membranes. The functional prediction of ABC systems reveals that most of them are involved in the import of nutrients. We have identified some of the ABC transporter genes are positively selected. The gene thiP coding for iron compound ABC transporter, which is known to be an important effector of virulence, showed evidence for positive selection. In summary, we identified six genes that involve in the Brucella pathogenesis and virulence showing signals of positive selection. Our study suggests that positive selection plays an important role in the pathogenesis.

The activation or inactivation of the genes involved in the transport, transcriptional regulators, and cell membranes are responsible for host specificity and virulence of Brucella [28]. We identified several genes in these categories to be positively selected. These genes may be major responsible factors for the invasion and protection of bacteria against host.

Our results indicated that the recombination is not a major force in the evolution of Brucella. On other hand, 56 genes (3.5 %) of core genome of Brucella was showing evidence for positive selection. This indicates that positive selection plays an important role in the evolution and adaptation of Brucella. The adaptive changes caused in these genes are may be due to the interaction with the host defence mechanisms. These adaptive changes will definitely increase the fitness of organism in response to various environmental stresses. The computational prediction of positively selected genes will provide promising targets for further researches in the mechanisms of immune evasion and the host-pathogen interaction in Brucella.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, New Delhi through DBT-Network Project on Brucellosis. The UGC-CAS, CEGS, NRCBS, DBT-IPLS, DST-PURSE Programs of School of Biological Sciences, Madurai Kamaraj University is gratefully acknowledged.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Competing Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

- 1.Orsi RH, Sun Q, Wiedmann M. Genome-wide analyses reveal lineage specific contributions of positive selection and recombination to the evolution of Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen L, Bollback JP, Dimmic M, Hubisz M, Nielsen R. Genes under positive selection in Escherichia coli. Genome Res. 2007;17:1336–1343. doi: 10.1101/gr.6254707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefebure T, Stanhope MJ. Evolution of the core and pan-genome of Streptococcus: positive selection, recombination, and genome composition. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R71. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Z, Wong WS, Nielsen R. Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Callaghan D, Whatmore AM. Brucella genomics as we enter the multi-genome era. Brief Funct Genomics. 2011;10:334–341. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elr026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franco MP, Mulder M, Gilman RH, Smits HL. Human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:775–786. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiang Z, Zheng W, He Y. BBP: Brucella genome annotation with literature mining and curation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:347. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su F, Ou HY, Tao F, Tang H, Xu P. PSP: rapid identification of orthologous coding genes under positive selection across multiple closely related prokaryotic genomes. BMC Genom. 2013;14:924. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Didelot X, Falush D. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics. 2007;175:1251–1266. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelman A, Rubin DB. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat Sci. 1992;7:457–472. doi: 10.1214/ss/1177011136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halling SM, Peterson-Burch BD, Bricker BJ, Zuerner RL, Qing Z, Li LL, Kapur V, Alt DP, Olsen SC. Completion of the genome sequence of Brucellaabortus and comparison to the highly similar genomes of Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2715–2726. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.8.2715-2726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sankarasubramanian J, Vishnu US, Sridhar J, Gunasekaran P, Rajendhran J. Pan-Genome of Brucella Species. Indian J Microbiol. 2015;55:88–101. doi: 10.1007/s12088-014-0486-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster JT, Beckstrom-Sternberg SM, Pearson T, Beckstrom-Sternberg JS, Chain PS, Roberto FF, Hnath J, Brettin T, Keim P. Whole-genome-based phylogeny and divergence of the genus Brucella. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2864–2870. doi: 10.1128/JB.01581-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tibayrenc M, Ayala FJ. Reproductive clonality of pathogens: a perspective on pathogenic viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasitic protozoa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E3305–E3313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212452109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dos Vultos T, Mestre O, Rauzier J, Golec M, Rastogi N, Rasolofo V, Tonjum T, Sola C, Matic I, Gicquel B. Evolution and diversity of clonal bacteria: the paradigm of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker S, Hanage WP, Holt KE. Navigating the future of bacterial molecular epidemiology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feil EJ, Cooper JE, Grundmann H, Robinson DA, Enright MC, Berendt T, Peacock SJ, Smith JM, Murphy M, Spratt BG, Moore CE, Day NPJ. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3307–3316. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3307-3316.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennemann L, Didelot X, Aebischer T, Kuhn S, Drescher B, Droege M, Reinhardtf R, Correag P, Meyerc TF, Josenhansa C, Falushh D, Suerbaum S. Helicobacter pylori genome evolution during human infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5033–5038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018444108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva C, Vinuesa P, Eguiarte LE, Souza V, Martinez-Romero E. Evolutionary genetics and biogeographic structure of Rhizobium gallicum sensu lato, a widely distributed bacterial symbiont of diverse legumes. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:4033–4050. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arvand M, Feil EJ, Giladi M, Boulouis HJ, Viezens J. Multi-locus sequence typing of Bartonella henselae isolates from three continents reveals hypervirulent and feline-associated clones. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim KM, Kim KW, Sung S, Kim H. A genome-wide identification of genes potentially associated with host specificity of Brucella species. J Microbiol. 2011;49:768–775. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-1084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valderas MW, Alcantara RB, Baumgartner JE, Bellaire BH, Robertson GT, Ng WL, Richardson JM, Winkler ME, Roop RM. Role of HdeA in acid resistance and virulence in Brucella abortus 2308. Vet Microbiol. 2005;107:307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangari FJ, Seoane A, Rodríguez MC, Aguero J, Lobo JMG. Characterization of the urease operon of Brucella abortus and assessment of its role in virulence of the bacterium. Infect Immun. 2007;75:774–780. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01244-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornback ML, Roop RM. The Brucella abortus xthA-1 gene product participates in base excision repair and resistance to oxidative killing but is not required for wild-type virulence in the mouse model. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1295–1300. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.4.1295-1300.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delrue RM, Lestrate P, Tibor A, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X. Brucella pathogenesis, genes identified from random large-scale screens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;231:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JA, Mayfield J. Identification of Brucella abortus OxyR and its role in control of catalase expression. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5631–5633. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.19.5631-5633.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsolis RM, Seshadri R, Santos RL, Sangari FJ, Lobo JMG, de Jong MF, Ren Q, Myers G, Brinkac LM, Nelson WC, Deboy RT, Angiuoli S, Khouri H, Dimitrov G, Robinson JR, Mulligan S, Walker RL, Elzer PE, Hassan KA, Paulsen IT. Genome degradation in Brucella ovis corresponds with narrowing of its host range and tissue tropism. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]