Abstract

Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae (NOVC) are increasingly frequently observed ubiquitous microorganisms occasionally responsible for intestinal and extra-intestinal infections. Most cases involve self-limiting gastroenteritis or ear and wound infections in immunocompetent patients. Bacteraemia, which have been described in patients with predisposing factors, are rare and poorly known, both on the clinical and therapeutic aspects. We describe a case of NOVC bacteraemia and a systematic literature review in PubMed conducted up to November 2014 using a combination of the following search terms: “Vibrio cholerae non-O1” and “bacter(a)emia”. The case was a 70 year-old healthy male subject returning from Senegal and suffering from NOVC bacteraemia associated with liver abscesses. Disease evolution was favourable after 2 months’ therapy (ceftriaxone then ciprofloxacin). Three hundred and fifty cases of NOVC bacteraemia have been identified in the literature. The majority of patients were male (77 %), with a median age of 56 years and presenting with predisposing conditions (96 %), such as cirrhosis (55 %) or malignant disease (20 %). Diarrhoea was inconstant (42 %). Mortality was 33 %. The source of infection, identified in only 25 % of cases, was seafood consumption (54 %) or contaminated water (30 %). Practitioners should be aware of these infections, in order to warn patients with predisposing conditions, on the risk of ingesting raw or undercooked seafood or bathing in potentially infected waters.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s40064-015-1346-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae, Bacteraemia, Abscess

Background

The genus Vibrio belongs to the Vibrionaceae family. Vibrio species are halophilic facultative anaerobic Gram-negative bacilli, which are ubiquitously distributed in marine and estuarine environments. Their presence is particularly well documented in Asia and Latin America and in the coastal waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Their density is increasing, particularly in filter-feeding shellfish, associated with high surface water temperature, especially during warmer months (13–25 °C), secondary to the proliferation of phytoplankton and zooplankton (Crim et al. 2014; Harris et al. 2012; Huehn et al. 2014). There is an increasing trend towards infection due to Vibrio. Despite under-diagnosis and under-reporting, especially for milder cases, they are the 6th pathogen transmitted through food in the USA, after Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shigella, Cryptosporidium and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (Crim et al. 2014; Huehn et al. 2014).

Over 200 serogroups compose the V. cholerae species, based on the surface O antigen of the lipopolysaccharide (Harris et al. 2012). The two major serogroups, O1 and O139, are responsible for epidemic cholera, an acute diarrheal disease leading to 28,000–142,000 deaths every year, according to the WHO. Bacteraemia associated with choleragenic vibrios is rare, possibly thanks to the ability of the cholera toxin, a non-invasive enterotoxin, to suppress induction of inflammation during infection (Fullner et al. 2002).

Non-choleragenic vibrios, including the other serogroups of the V. cholerae species, and other species of Vibrio, mainly V. alginolyticus, V parahaemolyticus and V. vulnificus, can lead to intestinal infections (gastroenteritis) as well as extra-intestinal manifestations (wound infections, external otitis and bacteraemia) through invasive mechanisms, with significant mortality.

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of reports of infections involving non-O1, non-O139 V. cholerae (NOVC). The majority were case reports of self-limiting gastroenteritis, ear and wound infections in immunocompetent patients or bacteraemia in immunocompromised hosts with predisposing medical conditions (Petsaris et al. 2010).

However, NOVC infection may rarely lead to invasive extraintestinal infection and potentially fatal bacteraemia in healthy patients (Mannion and Mellor 1986). We report a case of NOVC bacteraemia with liver abscesses in a French immunocompetent male subject returning from Senegal, and discuss the epidemiology, the clinical manifestations, the predisposing factors and the antimicrobial therapy of NOVC bacteraemia through a review of 350 identified cases.

Methods

A review of the literature in English, French and Spanish was conducted via an electronic search on MEDLINE by crossing the key words “Vibrio cholerae non-O1” and “bacter(a)emia”. We also retrieved the articles in the reference lists of papers found in our searches. The literature search period ranged from the first described case in 1974 to November 2014.

Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.0.3 statistical software. Categorical variables were reported as percentages and compared using Chi square or Fisher’s exact tests according to expected frequencies. Continuous variables were expressed as means and analysed using Student’s t-test. A p-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Case report

A 70 year-old man was referred to the Infectious Diseases Unit in our institution in April 2010 for fever and watery diarrhoea, after spending 3 weeks in Senegal.

The patient presented with a previous history of myocardial infarction, hypertension, hepatitis A in 1954 and cholecystectomy. No alcohol abuse, malignant or immunocompromising disease was reported.

The patient presented with a single episode of watery diarrhoea, vomiting and dizziness associated with a short loss of consciousness on the day of his return to France and a 3-kg weight loss. Over the following days, he complained of high fever with chills and abdominal pain. The patient stated no history of bathing in the sea or in fresh water; however, he reported important consumption of fish and shellfish, sometimes undercooked, whereas no other case was reported among his fellow travellers.

On arrival, his body temperature was 38.1 °C and his vital signs were stable. The results of physical examination were normal with the exception of abdominal tenderness, mainly on the upper right quadrant. No jaundice was reported.

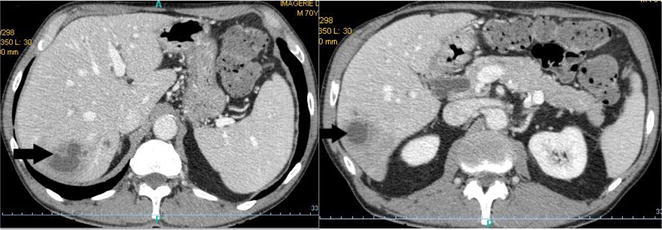

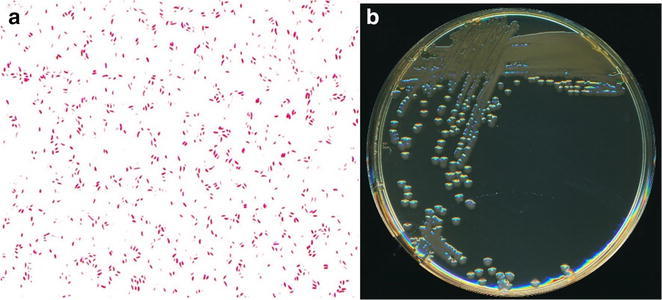

Laboratory tests revealed an increased white blood cell count (13 × 109/L) and elevated C-reactive protein (397 mg/L). Serum creatinine was within the reference range. Liver function test results were elevated, including aspartate aminotransferase, 119 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 216 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase, 163 IU/L, without hepatocellular insufficiency. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed two heterogenous collections from 3 to 5 cm in the right liver compatible with abscesses, confirmed by CT scan (Fig. 1). Neither of the two imaging techniques showed any signs of underlying chronic hepatopathy, nor damage on biliary ducts or portal vessel. One of the two sets of blood cultures collected upon admission yielded a Gram-negative rod, compatible with V. cholerae (Fig. 2). Stool cultures were negative. The strain was sent to the French National Reference Center for Vibrios and Cholera (CNRVC, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) for confirmation of the identification by biochemical, molecular and cultural methods, agglutination with O1 and O139 antisera and search for virulence factors. The strain did not agglutinate when tested against O1 or O139 antisera. PCR techniques demonstrated the absence of the major virulence-encoding genes of toxigenic V. cholerae, the cholera-toxin (ctxA and ctxB) and the toxin-coregulated pilus (tcpA) virulence genes, and of the stn gene, encoding a heat-stable enterotoxin reported to contribute to the pathogenicity of NOVC. PCR was positive for the El-Tor hlyA gene. The bacteria was sensitive to amoxicillin, cefotaxime, ofloxacin, gentamicin, cotrimoxazole.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal CT showing two low density lesions in the right liver (arrows), compatible with the diagnosis of liver abscesses

Fig. 2.

a Gram stain (magnificence ×1000) and b colonial morphology of non-O1, non-O139 V. cholerae grown on Trypticase-Soy agar after 18 h of aerobic incubation at 35 °C (Photos M. Auzou)

Empirical parenteral treatment with intravenous ceftriaxone (1 g every 24 h) was initiated then shifted to oral ciprofloxacin (500 mg every 12 h) after 15 days. Clinical evolution was favourable, with a rapid decrease in fever and resolution of abdominal pain. After 2 months’ treatment, abdominal ultrasound did not reveal any residual collection and antibiotic therapy was stopped.

Results of the literature review

One hundred and twenty-eight articles described 350 cases of NOVC bacteraemia involving 347 patients, 3 of whom presented with a second episode (Additional file 1: Table S1) (Petsaris et al. 2010; Mannion and Mellor 1986; Lai et al. 2012; Morris et al. 1981; Anderson et al. 2004; Pierce et al. 2000; Hlady and Klontz 1996; Magnusson and Pegg 1996; Robins-Browne et al. 1977; Eltahawy et al. 2004; Marcenac et al. 1991; Ferreira et al. 2012; Zarate et al. 2011; Goei and Karthigasu 1978; Trubiano et al. 2014; Heath et al. 2001; Guard et al. 1980; Hsu et al. 2013; Huhulescu et al. 2007; Halabi et al. 1997; Berghmans et al. 2002; Kadkhoda et al. 2012; Burns et al. 1989; Ramsingh 1998; Briceno et al. 2009; Young et al. 1991; Lu et al. 2014; Farmachidi et al. 2003; Chong et al. 1985; Choi et al. 2003; Dalsgaard et al. 2000; Marek et al. 2013; Aguinaga et al. 2009; Forné et al. 1987; Prats et al. 1975; Lopez-Brea et al. 1985; Mirelis et al. 1987; Royo et al. 1993; Mauri et al. 1987; Esparcia et al. 2000; Fernández et al. 2000; Lantero et al. 1984; Folgueira et al. 1991; Fernández-Monrás et al. 1990; Catalá Barceló MT 1998; Fernández-Natal and Alcoba-Leza 1996; Calduch Broseta JV 2003; Rabadan and Vilalta 1989; Rubin et al. 1981; Nedunchezian et al. 1994; Pitrak and Gindorf 1989; Bonner et al. 1983; Newman et al. 1993; Namdari et al. 2000; Patel et al. 2009; Wagner et al. 1995; Siegel and Rogers 1982; McCleskey et al. 1986; Florman et al. 1990; West et al. 1998; Klontz 1990; Hughes et al. 1978; Restrepo et al. 2006; Safrin et al. 1988; Fearrington et al. 1974; Shannon and Kimbrough 2006; Platia and Vosti 1980; Kontoyiannis et al. 1995; Shelton et al. 1993; Crump et al. 2003; Naidu et al. 1993; Morgan et al. 1985; Lukinmaa et al. 2006; Blanche and Sicard 1994; Moinard et al. 1989; Laudat et al. 1997; Raultin and de La Roy, 1981; Couzigou et al. 2007; Issack et al. 2008; Kerketta et al. 2002; Thomas et al. 1996; Lalitha et al. 1986; George et al. 2013; Raju et al. 1990; Khan et al. 2013; Toeg et al. 1990; Rudensky et al. 1993; Farina et al. 1999; Piersimoni et al. 1991; Ismail et al. 2001; Dhar et al. 1989, 2004; Phetsouvanh et al. 2008; Feghali and Adib 2011; Tan et al. 1994; Deris and Leow 2009; Whittaker 2013; Stypulkowska-Misiurewicz et al. 2006; Albuquerque et al. 2013; El-Hiday and Khan 2006; Khan et al. 2007; Strumbelj et al. 2005; Wiström 1989; Lin et al. 1996; Ko et al. 1998; Lee et al. 1993; Chang-Chien 2006; Tsai and Huang 2009; Chan et al. 1994; Yang et al. 2008; Cheng et al. 2004; Tsai et al. 2004; Wang et al. 1991; Laosombat et al. 1996; Punpanich et al. 2011; Thisyakorn and Reinprayoon 1990; Luxsameesathaporn et al. 2012; Suankratay et al. 2001; Wiwatworapan and Insiripong 2008; Boukadida et al. 1993; Lan et al. 2014; Geneste et al. 1995; Yang et al. 2011; Thomas et al. 2007; Ou et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2007; Thamlikitkul 1990; Jesudason et al. 1991). The majority of articles were case reports, the largest series including 69 cases of bacteraemia (Ou et al. 2003). The first case was described in the USA in 1974 (Fearrington et al. 1974). One hundred and fifty-six cases (45 %) originated from Taiwan, 60/350 (20 %) from the USA and 21/350 (6 %) from Spain. Although NOVC strains are frequently found in coastal waters, only two cases have been reported in Africa. Two possible explanations are under-diagnosis due to lack of resources, and the non reporting of clinical cases. Including our own case report, 12 cases of NOVC bacteraemia have been published in France, in summer or autumn, including four imported cases from Tunisia (2), Morocco (1) and Senegal (1) (Farmachidi et al. 2003; Blanche and Sicard 1994; Moinard et al. 1989; Laudat et al. 1997; Raultin and de La Roy, 1981; Couzigou et al. 2007).

NOVC infection predominantly affected middle-aged male subjects (median age 56 years, sex-ratio 3.3) and rarely children <18 years (4.6 %). The main risk factor for NOVC bacteraemia was cirrhosis (54 %). Other risk factors were cancer or malignant blood diseases, alcoholism, other liver diseases, diabetes, and iatrogenesis (Additional file 1: Table S1).

When specified, the source of NOVC bacteraemia was most often seafood consumption (53.9 %) including oysters (9/22, 41 %), fish (5/22, 23 %), shrimps (4/22, 18 %), clams (2/22, 9 %), mussels (1/22, 4 %) and apple snail (1/22, 4 %) (Additional file 1: Table S1) (Crim et al. 2014; Morris et al. 1981; Anderson et al. 2004; Pierce et al. 2000; Trubiano et al. 2014; Halabi et al. 1997; Dalsgaard et al. 2000; Marek et al. 2013).

The clinical presentation of bacteraemia was most often hypo or hyperthermia, diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Jaundice and ascites were probably linked to cirrhosis (Additional file 1: Table S1). When specified, diarrhoea was most often watery (20/25, 80 %), rarely bloody (12 %) or with mucous (8 %). Including our patient, five hepatic abscesses were described, one of which yielded sterile blood cultures (Guard et al. 1980; Farmachidi et al. 2003; Strumbelj et al. 2005; Lai et al. 2011). Two cases of pyomyositis were also reported (Nedunchezian et al. 1994; Couzigou et al. 2007), as well as one prostatic abscess (Safrin et al. 1988), one cerebral abscess (Morgan et al. 1985) and one peritoneal abscess (Stypulkowska-Misiurewicz et al. 2006). This significant frequency of abscess, almost 5 %, had not been reported to date.

One-third of patients with NOVC bacteraemia died.

Prognostic factors were studied based on articles for which clinical outcomes were known. Hypotension and confusion or coma were statistically associated with a higher mortality, whereas digestive surgery was associated with better outcome (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Discussion

This work represents the largest literature review on epidemiology, risk factors and prognosis of an unusual and potentially emerging pathogen, namely, non-O1, non-O139 V. cholerae.

The three main clinical presentations of NOVC infection are gastroenteritis, wound and ear infections and bacteraemia, the latter being the least frequent (Petsaris et al. 2010). However, strains have been isolated from various other sites, such as respiratory tract, bile, uterus, urine and cerebrospinal fluid (Lai et al. 2012). Gastroenteritis can be mild to severe, with watery more often than bloody stools, but, in all cases, prognosis is favourable (Morris et al. 1981; Anderson et al. 2004). They are however under-diagnosed, partly due to the failure of both clinicians and microbiologist to suspect vibrios as etiological agents of diarrhoea, and to the fact that many laboratories do not use the appropriate enrichment and culture media, such as thiosulfate-citrate-bile salt-sucrose (TCBS) agar, to isolate these organisms (Pierce et al. 2000). Between 1 and 3.4 % of cases of acute diarrhoea are believed to be due to NOVC, in developing and developed countries alike (Luo et al. 2013). NOVC grows in routine blood culture media. However, due to its rarity, NOVC bacteraemia is relatively unknown [17 % of NOVC infections in Florida were bacteraemia (Hlady and Klontz 1996)].

Most bacteraemia cases are associated with exposure to aquatic environments or seafood consumption, with 5.6 % of seafood samples tested in Italy positive for NOVC (Ottaviani et al. 2009), and more than one-third of seafood samples tested in Germany (Huehn et al. 2014; Cheasty et al. 1999). Bacteria may shift from the intestine to the blood through the portal vein or intestinal lymphatic system (Bonner et al. 1983). However, in almost 75 % of cases, no exposure to aquatic environments or seafood consumption was reported, suggesting other infection routes (Additional file 1: Table S1). Indeed, NOVC strains have been isolated from wild and domestic animals (Cheasty et al. 1999), while asymptomatic human carriage has also been described and two outbreaks of NOVC gastroenteritis have been linked to the consumption of grated eggs and potatoes (Morris et al. 1981; Dhar et al. 2004). NOVC can grow in water with low salinity, such as alkaline lakes, artificial waterways and sewers. It has been documented in French coastal waters (Hervio-Heath et al. 2002).

Subtyping methods, such as Pulsed Field Gel electrophoresis analysis, indicated that NOVC strains showed considerable diversity. The mechanisms underlying their virulence and in particular their capacity to invade the bloodstream are still not fully understood. These strains normally lack most of the major virulence-encoding regions of toxigenic V. cholerae (such as cholera toxin or toxin-coregulated pilus), but their pathogenicity has been associated with other virulence factors. Among them, a type III secretion system has been demonstrated to be involved in colonization (Chaand et al. 2015), a heat-stable enterotoxin (ST), encoded by the stn gene, was reported to contribute to the pathogenicity of these strains in case of gastroenteritis (Morris et al. 1990), a haemagglutinin protease (HA/P), and a haemolysin, present in V. cholerae O1, was suggested to be involved in the enteroinvasiveness of some NOVC isolates (Namdari et al. 2000; Luo et al. 2013; Ottaviani et al. 2009; Awasthi et al. 2013; Schirmeister et al. 2014). However, the lack of detection of stn gene in most of the strains associated with gastroenteritis (data from the CNRVC), the presence and expression of hlyA genes in strains isolated from patients without extraintestinal infection (Ottaviani et al. 2009, and data from the CNRVC) and its widespread occurrence among environmental strains, suggest that there are additional virulence factors.

Occurrence of NOVC bacteraemia is dependent on the infecting strain, but also on the health and immune status of the host. The main risk factor of NOVC bacteraemia is cirrhosis (54 %). Cirrhotic patient susceptibility to NOVC bacteraemia is thought to be linked to inflammation and oedema of intestinal mucosa with increased intestinal permeability, by-pass of the hepatic reticuloendothelial system by portal hypertension, weak opsonic activity of ascetic fluid, impairment of phagocytosis, complement deficiencies, alteration of iron metabolism and/or inhibition of chemotaxis, the precise role of each defence mechanism defect requiring further study (Anderson et al. 2004; Bonner et al. 1983; Couzigou et al. 2007; Ko et al. 1998).

In published cases of NOVC bacteraemia, there is extreme heterogeneity in antimicrobial therapy (in terms of the nature of antimicrobial agent(s), their dosage and treatment duration). In cholera, antimicrobial therapy, although adjunctive, is relatively well codified, reducing total stool volume by 50 %, the duration of shedding of viable organisms in stools from several days to 1–2 days and the quantity of rehydration fluids by 40 %. Tetracycline and azithromycin appear to be first-choice antibiotics (Leibovici-Weissman et al. 2014). Because NOVC bacteraemia is rare, no large-scale trials have been conducted. While spontaneous recovery is the rule in NOVC gastroenteritis, antimicrobial therapy is recommended in complicated forms and/or in immunocompromised patients, with a dual-agent therapy in NOVC bacteraemia according to certain authors (Couzigou et al. 2007). Tetracyclines are widely used, by analogy with cholera and because they inhibit protein synthesis, which may decrease the production of toxins (Leibovici-Weissman et al. 2014). Ko et al. (1998) reported the synergistic effect, both in vitro and in mice, of cefotaxime plus minocycline in V. vulnificus infections. Thus, the association of third-generation cephalosporins with a tetracycline or fluoroquinolones may offer an interesting alternative in the treatment of NOVC bacteraemia, depending on local antibiotic susceptibility testing, although recommendations regarding the choice of therapy are not conclusive. Furthermore, several cases of antimicrobial resistance have been described in environmental as well as in clinical strains, involving cefotaxime, nalidixic acid, tetracyclines, cotrimoxazole, ciprofloxacin and depending on location, certain multidrug resistant strains having been reported, particularly in India (Lu et al. 2014; Luo et al. 2013; Jagadeeshan et al. 2009). The duration of treatment is also a matter of debate, ranging from 3 to 75 days with a median of 14 days (Additional file 1: Table S1). This duration should probably be adapted according to the patient’s background, clinical presentation and severity (such as meningitis and abscess).

In our review, we didn’t observe a higher risk of mortality in patients with cirrhosis, neoplasia and iatrogenesis, unlike Ou et al. (2003). Unsurprisingly, the onset of circulatory or neurological failure was statistically associated with higher mortality. Digestive surgery seems paradoxically protective, because it does not impair the immune system, as do cirrhosis or cancer. The high mortality of bacteremia NOVC is probably due to delayed diagnosis, inadequate antimicrobial therapy and/or too short therapy duration.

Conclusions

Ongoing global warming, anthropisation of coastal environments, international seafood trade, consumption of undercooked seafood and increase in individuals at risk will undoubtedly increase NOVC infections, especially in summer, as already demonstrated in the Baltic Sea (Huehn et al. 2014; Schirmeister et al. 2014), and will render NOVC infection an under-diagnosed, life-threatening, emerging infectious disease, involving economic issues (seafood importation) (Robert-Pillot et al. 2014). NOVC strains have been confirmed as potential contaminants of widely consumed food types in France, and are also present in shellfish and water samples collected from French coastal and estuarine areas (Hervio-Heath et al. 2002).

So there is a need to increase the capacity to ensure prompt diagnosis and public health notification and investigation for effective patient management and infection control. Physicians in temperate countries should be aware of these infections, to ensure they request the detection of Vibrio in faeces in cases of gastroenteritis after seafood consumption, and to ensure they warn individuals, particularly those presenting with predisposing conditions for bacteraemia (liver disease, alcoholism, diabetes, neoplasia) on the risk of ingesting raw or undercooked seafood or bathing in potentially infected waters during warm summers. All cases must be reported and confirmed by the National Reference Centre.

Authors’ contributions

SD and ADLB designed the study and wrote the manuscript. SD and JJP performed the statistical analyses. All the authors read and critically commented on the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no one else to thank for conception, design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, draft or revising the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial support No benefit in any form have been or will be received from commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

Ethical approval The patient had given its written informed consent for the use of his personal and medical information for the publication of this study. Because this study was only a review, it didn’t require ethical approval.

Additional file

10.1186/s40064-015-1346-3 Results from systematic literature review of 350 non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia.

Contributor Information

S. Deshayes, Email: samuel.deshayes@gmail.com

C. Daurel, Email: daurel-c@chu-caen.fr

V. Cattoir, Email: cattoir-v@chu-caen.fr

J.-J. Parienti, Email: parienti-jj@chu-caen.fr

M.-L. Quilici, Email: vibrions@pasteur.fr

A. de La Blanchardière, Phone: +33633189289, Email: delablanchardiere-a@chu-caen.fr

References

- Aguinaga A, Portillo ME, Yuste JR, del Pozo JL, Garcia-Tutor E, Perez-Gracia JL, Leiva J. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae inguinal skin and soft tissue infection with bullous skin lesions in a patient with a penis squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2009;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque A, Cardoso H, Pinheiro D, Macedo G. Vibrio cholerae non-O1 and non-O139 bacteremia in a non-traveler Portuguese cirrhotic patient: first case report. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;36:309–310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AML, Varkey JB, Petti CA, Liddle RA, Frothingham R, Woods CW. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae septicemia: case report, discussion of literature, and relevance to bioterrorism. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;49(295–7):46. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi SP, Asakura M, Chowdhury N, Neogi SB, Hinenoya A, Golbar HM, Yamate J, Arakawa E, Tada T, Ramamurthy T, Yamasaki S. Novel cholix toxin variants, ADP-ribosylating toxins in Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 strains, and their pathogenicity. Infect Immun. 2013;81:531–541. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00982-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghmans T, Crokaert F, Sculier JP. Vibrio cholerae bacteremia in a neutropenic patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;21:676–678. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0794-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanche P, Sicard D, Sevali Garcia J, Paul G, Fournier JM. Septicemia due to non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:813. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner JR, Coker AS, Berryman CR, Pollock HM. Spectrum of Vibrio infections in a Gulf Coast community. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:464–469. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-4-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukadida J, Souguir S, Chelbi S, Said R, Jeddi M. Septicémie à Vibrio cholerae non 01. Méd Mal Infect. 1993;23:565–567. doi: 10.1016/S0399-077X(05)81123-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briceno LI, Puebla AC, Guerra AF, Jensen FD, Nunez BH, Ulloa FMT, Osorio ACG. Non-toxigenic hemolytic Vibrio cholerae non-O1 non-O139 fatal septicemia. Report of one case. Rev Med Chil. 2009;137:1193–1196. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872009000900008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KD, Yurack J, McIntyre RW. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae septicemia associated with a motor vehicle accident. CMAJ. 1989;140:1334–1335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calduch Broseta JV, Segarra Soria MM, Colomina Avilés J, Llorca Ferrandiz C, Pascual Pérez R, JV Septicemia caused by Vibrio cholerae non-01 in immunocompromised patient. An Med Interna. 2003;20:630–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalá Barceló MT, Núñez Sánchez JC, Balaguer Martínez R, Borrás Salvador R. Vibrio cholerae non 01 sepsis in a healthy patient: review of reported cases in Spain. Rev Clin Esp. 1998;198:850–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaand M, Miller KA, Sofia MK, Schlesener C, Weaver JW, Sood V, Dziejman M. Type 3 secretion system island encoded proteins required for colonization by non-O1/non-O139 serogroup V. cholerae. Infect Immun. 2015;83:2862–2869. doi: 10.1128/IAI.03020-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HL, Ho HC, Kuo TT. Cutaneous manifestations of non-01 Vibrio cholerae septicemia with gastroenteritis and meningitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:626–628. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang-Chien C-H. Bacteraemic necrotizing fasciitis with compartment syndrome caused by non-O1 Vibrio cholerae. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1381–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheasty T, Said B, Threlfall EJ. V cholerae non-O1: implications for man? Lancet. 1999;354:89–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N-C, Tsai J-L, Kuo Y-S, Hsueh P-R. Bacteremic necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroup O56 in a patient with liver cirrhosis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103:935–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SM, Lee DG, Kim MS, Park YH, Kim YJ, Lee S, Kim HJ, Choi JH, Yoo JH, Kim DW, Min WS, Shin WS, Kim CC. Bacteremic cellulitis caused by non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae in a patient following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2003;31:1181–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong Y, Kwon OH, Lee SY, Kim BS, Min JS. Non-O group 1 Vibrio cholerae septicemia and peritonitis. Report of two cases. Yonsei Med J. 1985;26:82–84. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1985.26.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzigou C, Lacombe K, Girard P-M, Vittecoq D, Meynard J-L. Non-O:1 and non-O:139 Vibrio cholerae septicemia and pyomyositis in an immunodeficient traveler returning from Tunisia. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2007;5:44–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crim SM, Iwamoto M, Huang JY, Griffin PM, Gilliss D, Cronquist AB, Cartter M, Tobin-D’Angelo M, Blythe D, Smith K, Lathrop S, Zansky S, Cieslak PR, Dunn J, Holt KG, Lance S, Tauxe R, Henao OL, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Incidence and trends of infection with pathogens transmitted commonly through food—Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. sites, 2006–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:328–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump JA, Bopp CA, Greene KD, Kubota KA, Middendorf RL, Wells JG, Mintz ED. Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serogroup O141-associated cholera-like diarrhea and bloodstream infection in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:866–868. doi: 10.1086/368330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard A, Forslund A, Hesselbjerg A, Bruun B. Clinical manifestations and characterization of extra-intestinal Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 infections in Denmark. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6:625–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deris ZZ, Leow VM, Wan Hassan WMN, Nik Lah NAZ, Lee SY, Siti Hawa H, Siti Asma H, Ravichandran M. Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia in splenectomised thalassaemic patient from Malaysia. Trop Biomed. 2009;26:320–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R, Ghafoor MA, Nasralah AY. Unusual non-serogroup O1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia associated with liver disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2853–2855. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2853-2855.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R, Badawi M, Qabazard Z, Albert MJ. Vibrio cholerae (non-O1, non-O139) sepsis in a child with Fanconi anemia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;50:287–289. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hiday AH, Khan FY, Al Maslamani M, El Shafie S. Bacteremia and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis due to Vibrio cholerae (non-O1 non-O139) in liver cirrhosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltahawy AT, Jiman-Fatani AA, Al-Alawi MM. A fatal non-01 Vibrio cholerae septicemia in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1730–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esparcia AM, Cañizares R, Roig P, Martínez A. Bacteremia by Vibrio cholerae no 01, two cases. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2000;18:49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina C, Luzzi I, Lorenzi N. Vibrio cholerae O2 sepsis in a patient with AIDS. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:203–205. doi: 10.1007/s100960050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmachidi J-P, Sobesky R, Boussougant Y, Quilici M-L, Coffin B. Septicaemia and liver abscesses secondary to non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:699–700. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200306000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearrington EL, Rand CH, Jr, Mewborn A, Wilkerson J. Letter: non-cholera Vibrio septicemia and meningoencephalitis. Ann Intern Med. 1974;81:401. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-81-3-401_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feghali R, Adib SM. Two cases of Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 septicaemia with favourable outcome in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:722–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández JM, Serrano M, De Arriba JJ, Sánchez MV, Escribano E, Ferreras P. Bacteremic cellulitis caused by Non-01, Non-0139 Vibrio cholerae: report of a case in a patient with hemochromatosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;37:77–80. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(99)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Monrás F, Vayreda E, Rosell F, Jané J. Bacteremia caused by Vibrio cholerae No. 01. Med Clin (Barc) 1990;94:596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Natal I, Alcoba-Leza M. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia without diarrhoea. Lancet. 1996;348:67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)64401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira N, Yantorno ML, Mileo H, Sorgentini M, Esposto A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis associated with Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 bacteremia. Rev Chil Infectol. 2012;29:547–550. doi: 10.4067/S0716-10182012000600014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florman AL, Cushing AH, Byers T, Popejoy S. Vibrio cholerae bacteremia in a 22-month-old New Mexican child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:63–65. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folgueira MD, López MM, García J, Peña P. Bacteremia caused by Vibrio cholerae non-01. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1991;9:254–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forné M, Matas E, Marti C, Pujol R, Garau J. Sepsis por Vibrio cholerae no 01. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1987;5:590–594. [Google Scholar]

- Fullner KJ, Boucher JC, Hanes MA, Haines GK, 3rd, Meehan BM, Walchle C, Sansonetti PJ, Mekalanos JJ. The contribution of accessory toxins of Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor to the proinflammatory response in a murine pulmonary cholera model. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1455–1462. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneste C, Dab W, Cabanes P, Vaillant V, Quilici M, Fournier J. Les vibrioses non cholériques en France : cas identifiés de 1995 à 1998 par le centre national de référence. BEH. 1995;2000:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- George N, Fredrick F, Mohapatra A, Veeraraghavan B, Kakde ST, Valson AT, Basu G. Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae sepsis in a patient with nephrotic syndrome. Indian J Nephrol. 2013;23:378–380. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.116329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goei SH, Karthigasu KT. Systemic vibriosis due to non-cholera Vibrio. Med J Aust. 1978;1:286–288. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1978.tb112550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guard RW, Brigden M, Desmarchelier P. Fulminating systemic infection caused by Vibrio cholerae species which does not agglutinate with 0–1 V. cholerae antiserum. Med J Aust. 1980;1:659–661. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1980.tb135213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabi M, Haditsch M, Renner F, Brinninger G, Mittermayer H. Vibrio cholerae non-O1 septicaemia in a patient with liver cirrhosis and Billroth-II-gastrectomy. J Infect. 1997;34:83–84. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(97)80016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Qadri F, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB. Cholera. Lancet. 2012;379:2466–2476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60436-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath CH, Garrow SC, Golledge CL. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae: a fatal cause of sepsis in northern Australia. Med J Aust. 2001;174:480–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervio-Heath D, Colwell RR, Derrien A, Robert-Pillot A, Fournier JM, Pommepuy M. Occurrence of pathogenic vibrios in coastal areas of France. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlady WG, Klontz KC. The epidemiology of Vibrio infections in Florida, 1981–1993. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1176–1183. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C-Y, Pollett S, Ferguson P, McMullan BJ, Sheppeard V, Mahady SE. Locally acquired severe non-O1 and non-O139 Vibrio cholerae infection associated with ingestion of imported seafood. Med J Aust. 2013;199:26–27. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huehn S, Eichhorn C, Urmersbach S, Breidenbach J, Bechlars S, Bier N, Alter T, Bartelt E, Frank C, Oberheitmann B, Gunzer F, Brennholt N, Böer S, Appel B, Dieckmann R, Strauch E. Pathogenic vibrios in environmental, seafood and clinical sources in Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014;304:843–850. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JM, Hollis DG, Gangarosa EJ, Weaver RE. Non-cholera Vibrio infections in the United States. Clinical, epidemiologic, and laboratory features. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:602–606. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-5-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhulescu S, Indra A, Feierl G, Stoeger A, Ruppitsch W, Sarkar B, Allerberger F. Occurrence of Vibrio cholerae serogroups other than O1 and O139 in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00508-006-0747-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail EA, Shafik MH, Al-Mutairi G. A case of non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae septicemia with meningitis, cerebral abscess and unilateral hydrocephalus in a preterm baby. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:598–600. doi: 10.1007/s100960100553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issack MI, Appiah D, Rassoul A, Unuth MN, Unuth-Lutchun N. Extraintestinal Vibrio infections in Mauritius. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2:397–399. doi: 10.3855/jidc.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagadeeshan S, Kumar P, Abraham WP, Thomas S. Multiresistant Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 from waters in South India: resistance patterns and virulence-associated gene profiles. J Basic Microbiol. 2009;49:538–544. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200900085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesudason MV, Lalitha MK, Koshi G. Non 01 Vibrio cholerae in intestinal and extra intestinal infections in Vellore, S. India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1991;34:26–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadkhoda K, Adam H, Gilmour MW, Hammond GW. Nontoxigenic Vibrio cholerae septicemia in an immunocompromised patient. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:1–3. doi: 10.1155/2012/698746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerketta JA, Paul AC, Kirubakaran VBC, Jesudason MV, Moses PD. Non-01 Vibrio cholerae septicemia and meningitis in a neonate. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:909–910. doi: 10.1007/BF02723720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan FY, El-Hiday A, El Shafie S, Abbas M. Non-O1 non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia and peritonitis associated with chronic liver disease. J Clin Diagn Res. 2007;1:296–298. [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Kumar A, Meparambu D, Thomas S, Harichandran D, Karim S. Fatal non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae septicaemia in a patient with chronic liver disease. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:917–921. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.049296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klontz KC. Fatalities associated with Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio cholerae non-O1 infections in Florida (1981 to 1988) South Med J. 1990;83:500–502. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko WC, Chuang YC, Huang GC, Hsu SY. Infections due to non-O1 Vibrio cholerae in southern Taiwan: predominance in cirrhotic patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:774–780. doi: 10.1086/514947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontoyiannis DP, Calia KE, Basgoz N, Calderwood SB. Primary septicemia caused by Vibrio cholerae non-O1 acquired on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1330–1333. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.5.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C-C, Liu W-L, Chiu Y-H, Chao C-M, Gau S-J, Hsueh P-R. Liver abscess due to non-O1 Vibrio cholerae in a cirrhotic patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Infect. 2011;62:235–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C-C, Liu W-L, Chiu Y-H, Gau S-J, Hsueh P-R. Spontaneous bacterial empyema due to non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae in a cirrhotic patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;73:84–85. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalitha MK, Dayal U, Cherian AM. Non-agglutinating Vibrio (non 0-1 V. cholerae) septicemia. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1986;29:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan N, Nga T, Yen N, Dung T, Tuyen H, Campbell J, Whitehorn J, Thwaites G, Chau N, Baker S. Two cases of bacteriemia caused by nontoxigenic, non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae isolates in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:3819–3821. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01915-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantero M, Perales I, Michaus L, Echevarría I, Diaz A, Aguirrezabal E. Non O1 Vibrio cholerae septicemia. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1984;2:62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laosombat V, Pruekprasert P, Wongchanchailert M. Non-0:1 Vibrio cholerae septicemia in thalassemia patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1996;27:411–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudat P, Jacob C, Chillou C, Dudragne D, Dodin A. A fatal non 01 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia in an immunocompetent patient contaminated in France. Méd Mal Infect. 1997;27:620–621. doi: 10.1016/S0399-077X(97)80097-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Leu HS, Huang SH. Bacteremic cellulitis caused by non-O1 Vibrio cholerae: report of a case. J Formos Med Assoc. 1993;92:472–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-L, Hung P-P, Tsai C-A, Lin Y-H, Liu C-E, Shi Z-Y. Clinical characteristics of non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae isolates and polymerase chain reaction analysis of their virulence factors. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:474–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovici-Weissman Y, Neuberger A, Bitterman R, Sinclair D, Salam MA, Paul M. Antimicrobial drugs for treating cholera. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD008625. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008625.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CJ, Chiu CT, Lin DY, Sheen IS, Lien JM. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia in patients with cirrhosis: 5-yr experience from a single medical center. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Brea M, Jimenez ML, de las Cuevas C, Alcala-Zamora J, Alonso P. Non-01 Vibrio cholerae septicaemia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79:878–879. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Zhou H, Li D, Li F, Zhu F, Cui Y, Huang L, Wang D. The first case of bacteraemia due to non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae from type 2 diabetes mellitus in mainland China. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;25:116–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukinmaa S, Mattila K, Lehtinen V, Hakkinen M, Koskela M, Siitonen A. Territorial waters of the Baltic Sea as a source of infections caused by Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139: report of 3 hospitalized cases. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;54:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Ye J, Jin D, Ding G, Zhang Z, Mei L, Octavia S, Lan R. Molecular analysis of non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae isolated from hospitalised patients in China. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxsameesathaporn P, Jariyasethpong T, Intalapaporn P, Chinapha A. Vibrio cholerae non O 1, non O 139 septicemia in a 19-year-old woman with beta-thalassemia/hemoglobin E disease. J Infect Dis Antimicrobial Agents. 2012;29:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson MR, Pegg SP. Vibrio cholerae non-O1 primary septicaemia following a large thermal burn. Burns. 1996;22:44–47. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannion P, Mellor S. Non-cholera vibrio bacteraemia associated with acute cholecystitis. Br Med J. 1986;292:450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6518.450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcenac FM, Gherardi C, Mattera J, Corrado C, Vay C, Fernández AJ. Sepsis due to Vibrio cholerae no 01. Medicina (B Aires) 1991;51:148–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek A, Inkster T, Anderson E, Jenkins C, Boyd J, Kerr S, Cowden J. Non-toxigenic Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia: case report and review of the literature. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1357–1359. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.060400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri M, Vernet M, Morera MA, García Restoy E. Bacteriemia por Vibrio cholerae. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1987;5:639–640. [Google Scholar]

- McCleskey FK, Hastings JR, Winn RE, Adams ED., Jr Non-01 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia—complication of a LeVeen shunt. Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;85:644–646. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/85.5.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirelis B, López P, Barrio J, Guillaumes S, Prats G. Sepsis por Vibrio cholerae no 01. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1987;5:640–641. [Google Scholar]

- Moinard D, Guiavarch PY, Caillon J, Barre P. Non 01 Vibrio cholerae septicemia. Presse Med. 1989;18:898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DR, Ball BD, Moore DG, Kohl S. Severe Vibrio cholerae sepsis and meningitis in a young infant. Tex Med. 1985;81:37–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JG, Wilson R, Davis BR, Wachsmuth IK, Riddle CF, Wathen HG, Pollard RA, Blake PA. Non-O group 1 Vibrio cholerae gastroenteritis in the United States: clinical, epidemiologic, and laboratory characteristics of sporadic cases. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:656–658. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-94-5-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JJ, Takeda T, Tall B, Losonsky G, Bhattacharya S, Forrest B, Kay B, Nishibuchi M. Experimental non-O group 1 Vibrio cholerae gastroenteritis in humans. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:697–705. doi: 10.1172/JCI114494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu LS, Bakerman PR, Saubolle MA, Lewis K. Vibrio cholerae non-0:1 meningitis in an infant. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:879–881. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namdari H, Klaips CR, Hughes JL. A cytotoxin-producing strain of Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 as a cause of cholera and bacteremia after consumption of raw clams. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3518–3519. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3518-3519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedunchezian D, Cook MA, Rakic M. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as a non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae abscess. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1553–1554. doi: 10.1002/art.1780371022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman C, Shepherd M, Woodard MD, Chopra AK, Tyring SK. Fatal septicemia and bullae caused by non-01 Vibrio cholerae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:909–912. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70269-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani D, Leoni F, Rocchegiani E, Santarelli S, Masini L, Di Trani V, Canonico C, Pianetti A, Tega L, Carraturo A. Prevalence and virulence properties of non-O1 non-O139 Vibrio cholerae strains from seafood and clinical samples collected in Italy. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;132:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou T-Y, Liu J-W, Leu H-S. Independent prognostic factors for fatality in patients with invasive Vibrio cholerae non-O1 infections. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36:117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NM, Wong M, Little E, Ramos AX, Kolli G, Fox KM, Melvin J, Moore A, Manch R. Vibrio cholerae non-O1 infection in cirrhotics: case report and literature review. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11:54–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2008.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petsaris O, Nousbaum JB, Quilici ML, Le Coadou G, Payan C, Abalain ML. Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia in a cirrhotic patient. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:1260–1262. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.021014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phetsouvanh R, Nakatsu M, Arakawa E, Davong V, Vongsouvath M, Lattana O, Moore CE, Nakamura S, Newton PN. Fatal bacteremia due to immotile Vibrio cholerae serogroup O21 in Vientiane, Laos—a case report. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2008;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce AB, Broughton SJ, Johnson PD, Grayson ML. Vibrio cholerae in Victoria. Med J Aust. 2000;172:44–46. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb123895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piersimoni C, Morbiducci V, Scalise G. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae gastroenteritis and bacteraemia. Lancet. 1991;337:791–792. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91409-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitrak DL, Gindorf JD. Bacteremic cellulitis caused by non-serogroup O1 Vibrio cholerae acquired in a freshwater inland lake. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2874–2876. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2874-2876.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platia E, Vosti KL. Non cholera Vibrio septicemia. West J Med. 1980;132:354–357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prats G, Mirelis B, Pericas R, Verger G. Letter: non-cholera Vibrio septicemia and meningoencephalitis. Ann Intern Med. 1975;82:848–849. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-6-848_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punpanich W, Sirikutt P, Waranawat N. Invasive Vibrio cholerae non-O1 non-0139 infection in a thalassemic child. J Med Assoc Thail. 2011;94(Suppl 3):S226–S230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabadan PM, Vilalta E. Non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:667. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju AZ, Mathai D, Jesudasan M, Suresh M, Kaur A, Abraham OC, Pulimood BM. Nonagglutinable Vibrio cholerae septicaemia. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38:665–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsingh R. Vibrio cholerae non-O1 on blood culture, Saskatchewan. Can Commun Dis Rep. 1998;24:180–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raultin De, de La Roy Y, Grignon B, Grollier G, Paute MC, Becq-Giraudon B, Briaud M, Matuchansky C, Tanzer J. Two cases of septicemia caused by Vibrio non cholerae or non-O1 Vibrio cholerae. Nouv Presse Med. 1981;10:2516–2517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo D, Huprikar SS, VanHorn K, Bottone EJ. O1 and non-O1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia produced by hemolytic strains. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;54:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Pillot A, Copin S, Himber C, Gay M, Quilici M-L. Occurrence of the three major Vibrio species pathogenic for human in seafood products consumed in France using real-time PCR. Int J Food Microbiol. 2014;189:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins-Browne RM, Still CS, Isaäcson M, Koornhof HJ, Appelbaum PC, Scragg JN. Pathogenic mechanisms of a non-agglutinable Vibrio cholerae strain: demonstration of invasive and enterotoxigenic properties. Infect Immun. 1977;18:542–545. doi: 10.1128/iai.18.2.542-545.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo G, Martín C, Fuentes E, Elía M, Fernández J, Cuesta A. Bacteremia caused by Vibrio cholerae no 0:1. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 1993;11:228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LG, Altman J, Epple LK, Yolken RH. Vibrio cholerae meningitis in a neonate. J Pediatr. 1981;98:940–942. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudensky B, Marcus EL, Isaacson M, Lefler E, Stamler B, Sechter I. Non-O group 1 Vibrio cholerae septicemia in Israel. Isr J Med Sci. 1993;29:54–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safrin S, Morris JG, Jr, Adams M, Pons V, Jacobs R, Conte JE., Jr Non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia: case report and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:1012–1017. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmeister F, Dieckmann R, Bechlars S, Bier N, Faruque SM, Strauch E. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 isolated from German and Austrian patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:767–778. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-2011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon JD, Kimbrough RC., 3rd Pulmonary cholera due to infection with a non-O1 Vibrio cholerae strain. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3459–3460. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02343-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton CH, 3rd, Martino RL, Ramsey KM. Recurrent non-0:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia in a patient with multiple myeloma. Cancer. 1993;72:105–107. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930701)72:1<105::AID-CNCR2820720120>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel MI, Rogers AI. Fatal non-01 Vibrio cholerae septicemia in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:1130–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumbelj I, Prelog I, Kotar T, Dovecar D, Petras T, Socan M. A case of Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 septicaemia in Slovenia, imported from Tunisia, July 2005. Euro Surveill. 2005;10(E051020):6. doi: 10.2807/esw.10.42.02817-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stypulkowska-Misiurewicz H, Pancer K, Roszkowiak A. Two unrelated cases of septicaemia due to Vibrio cholerae non-O1, non-O139 in Poland, July and August 2006. Euro Surveill. 2006;11(E061130):2. doi: 10.2807/esw.11.48.03088-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suankratay C, Phantumchinda K, Tachawiboonsak W, Wilde H. Non-serogroup O:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia and cerebritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E117–E119. doi: 10.1086/319596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KK, Sin KS, Ng AJ, Yahya H, Kaur P. Non-O1 Vibrio cholerae septicaemia: a case report. Singap Med J. 1994;35:648–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamlikitkul V. Vibrio bacteremia in Siriraj Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 1990;73:136–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisyakorn U, Reinprayoon S. Non-01 Vibrio cholerae septicemia: a case report. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1990;21:149–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Cherian T, Raghupathy P. Non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia and peritonitis in a patient with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:276–277. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199603000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Straif-Bourgeois S, Sokol TM, Ratard RC. Vibrio infections in Louisiana: twenty-five years of surveillance 1980–2005. J La State Med Soc. 2007;159(205–8):210–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toeg A, Berger SA, Battat A, Hoffman M, Yust I. Vibrio cholerae bacteremia associated with gastrectomy. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:603–604. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.603-604.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trubiano JA, Lee JYH, Valcanis M, Gregory J, Sutton BA, Holmes NE. Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia in an Australian population. Intern Med J. 2014;44:508–511. doi: 10.1111/imj.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai Y-H, Hsu RW-W, Huang K-C, Chen C-H, Cheng C-C, Peng K-T, Huang T-J (2004) Systemic Vibrio infection presenting as necrotizing fasciitis and sepsis. A series of thirteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-A:2497–2502 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tsai Y-H, Huang T-J, Hsu RW-W, Weng Y-J, Hsu W-H, Huang K-C, Peng K-T. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections and primary sepsis caused by Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio cholerae non-O1. J Trauma. 2009;66:899–905. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31816a9ed3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner PD, Evans SD, Dunlap J, Ballon-Landa G. Necrotizing fasciitis and septic shock caused by Vibrio cholerae acquired in San Diego, California. West J Med. 1995;163:375–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Chao CH, Liu IM, Liu CY. Non-0:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia: a case report and literature review. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 1991;48:232–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West BC, Silberman R, Otterson WN. Acalculous cholecystitis and septicemia caused by non-O1 Vibrio cholerae: first reported case and review of biliary infections with Vibrio cholerae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;30:187–191. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(97)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker SJ. Shellfish-acquired Vibrio cholerae cellulitis and sepsis from a vulnerable leg. N Z Med J. 2013;126:95–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiström J. A case of non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia from northern Europe. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:732. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiwatworapan W, Insiripong S. Non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae septicemia with peritonitis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39:1098–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C-C, Lee B-J, Yang S-S, Lin Y-H, Lee Y-L. A case of non-O1 and non-O139 Vibrio cholerae septicemia with endophthalmitis in a cirrhotic patient. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008;61:475–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C-J, Wang C-S, Lu P-L, Chen T-C, Chen Y-H, Huang M-S, Lin C-C, Hwang J-J. Bullous cellulitis in cirrhotic patients—a rare but life-threatening infection caused by non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:861–862. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.024497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young CC, Chuang YC, Young CD. Non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia: report of two cases. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1991;65:1479–1483. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.65.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate MS, Giannico M, Colombrero C, Smayevsky J. Non-O1, non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteremia in a chronic hemodialysis patient. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2011;43:81–83. doi: 10.1590/S0325-75412011000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]