Abstract

Background

Palm kernel cake (PKC), a by-product of the palm oil industry is abundantly available in many tropical and subtropical countries. The product is known to contain high levels of phenolic compounds that may impede the deleterious effects of fungal mycotoxins. This study focused on the evaluation of PKC phenolics as a potential cytoprotective agent towards aflatoxin B1 (AFB1)-induced cell damage.

Methods

The phenolic compounds of PKC were obtained by solvent extraction and the product rich in phenolic compounds was labeled as phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF). This fraction was evaluated for its phenolic compounds composition. The antioxidant activity of PEF was determined by using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazil scavenging activity, ferric reducing antioxidant power, inhibition of ß-carotene bleaching, and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assays. The cytotoxicity assay and molecular biomarkers analyses were performed to evaluate the cytoprotective effects of PEF towards aflatoxin B1 (AFB1)-induced cell damage.

Results

The results showed that PEF contained gallic acid, pyrogallol, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, syringic acid, epicatechin, catechin and ferulic acid. The PEF exhibited free radical scavenging activity, ferric reducing antioxidant power, ß-carotene bleaching inhibition and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances inhibition. The PEF demonstrated cytoprotective effects in AFB1-treated chicken hepatocytes by reducing the cellular lipid peroxidation and enhancing antioxidant enzymes production. The viability of AFB1-treated hepatocytes was improved by PEF through up-regulation of oxidative stress tolerance genes and down-regulation of pro-inflammatory and apoptosis associated genes.

Conclusions

The present findings supported the proposition that the phenolic compounds present in PKC could be a potential cytoprotective agent towards AFB1 cytotoxicity.

Keywords: Aflatoxin B1, Cytoprotection, Oxidative stress, Antioxidant enzyme, Molecular mechanism, Apoptosis

Background

Aflatoxins produced by Aspergillus species, can be ubiquitously found in many foodstuffs. The aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) produced by both Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus is considered the most toxic among the mycotoxins [1]. Upon ingestion, this mycotoxin causes hepatotoxicity and alters the blood and immunological parameters [2]. The AFB1 triggers the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in different organs, impairs the antioxidant/pro-oxidant imbalance, elevates lipid peroxidation and damages biological molecules including lipids, proteins and DNA. The combination of these manifestations leads to oxidative stress and initiates the malfunction of the liver, which is the main detoxifying organ in the body [3, 4].

Recent studies suggested that plant phenolics and flavonoids are capable of adsorbing mycotoxins and alleviating their side effects in animals. The adsorption of toxic metabolites including aflatoxins, ochratoxins and fumonisins, boosts liver function and consequently enhances animal health and production [3, 5–7]. In this respect, phenolics, including sylimarin [8], rosmarinic acid [9], carnosic acid [10], catechins [11, 12] hesperidin [13], thymol [3] and quercetin [6] have been found to posses cytoprotective effects. However, none of these compounds have been commercialised as AFB1 cytoprotective agents due to their limited supply. Consequently, easily available sources of phenolic compounds such as agro-industrial by-products should be considered as an alternative source of these metabolites. The palm kernel cake (PKC), the residue from the kernel during oil extraction, would offer a sustainable source of phenolic compounds as the by-product is abundantly produced in countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, India, Nigeria, Colombia and Ivory Coast [14, 15].

Some reports are available on the phenolic compounds present in the palm oil and leaf [16], but information concerning the characteristics and function of phenolic compounds present in the PKC is rather limited and inconclusive. Therefore, we hypotised that the phenolics present in PKC may have antioxidant potential to impede the AFB1 cytotoxixity effects. In this regard, chicken hepatocytes, as one of the most sensitive cells to AFB1 manifestations, were used to evaluate the cytoprotective effects of PKC phenolics and to determine the underlying mechanisms of protection against AFB1 cytotoxicity.

Methods

Agriculture by-product

The expeller type PKC was obtained from Oil Mill Sdn Bhd., Dengkil, Selangor, Malaysia. The samples were freeze dried (Labconco, Kansas City, USA) and ground (mesh 100) using a laboratory grinder and stored at –20 °C before used.

Extraction of phenolic compounds

The reflux extraction technique was applied to extract the phenolic compounds in PKC following the method as described by Crozier et al. [17]. Briefly, 5 g of dried PKC powder were transferred into a 500 ml round-bottom flask and 160 ml of methanol were added, followed by 40 ml of 6 M HCL solution. The flask was then heated for two hours at 90 °C and the mixture was filtered (No. 1, Whatman, England). The methanol was removed under vacuum using a Rotary Evaporator (Rotavapour Buchii, Flawil, Switzerland) and the aqueous phase was then washed using n-hexane (20 ml) and subjected to liquid-liquid extraction with diethyl ether (3 × 20 ml) and ethyl acetate (3 × 20 ml). The organic solvents were then removed by using a Rotary Evaporator (Buchii, Switzerland) at 50 °C. The dried fraction obtained was weighed and reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide and labeled as PKC phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF).

Total phenolic contents

The total phenolic content (TPC) of PEF was determined according to the method described by Ismail et al. [18]. The PEF solution (0.5 ml) was mixed with 2.5 ml Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (previously diluted with water 1:10, v/v) and 2 ml sodium carbonate solution (7.5 %, w/v) and subsequently incubated for 90 min in the dark. The absorbance of the mixture was determined using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 765 nm and the result was expressed as milligram of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per gram of dried PEF.

Analyses of phenolic compounds by HPLC

To determine the quantity and types of phenolic compounds, the PEF was analysed by a high performance liquid chromatograph (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with an analytical column (Intersil ODS-3, 5 μm 4.6x150 mm, Gl Science Inc) as described by Karimi et al. [19].

The mobile phase consisted of deionized water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The pH of deionized water was adjusted to 2.5 with trifluoroacetic acid. The column was equilibrated by 85 % solvent A and 15 % solvent B. The elution was established by increasing the ratio of solvent B from 15 % to 85 % in 50 min. Then, the solvent B was decreased to 15 % in the next 5 min and this ratio was maintained for an extra 10 min for re-equilibration. The flow rate was 0.6 ml/min and the phenolic compounds were detected at 280 nm. For quantification of phenolic compounds, a calibration curve was prepared by injection of different standard compounds. The results were expressed as milligram of each phenolic compound per gram of dried PEF.

Antioxidant activity

Radicals scavenging activity

The 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazil (DPPH) free radicals were used to evaluate the radical scavenging activity of PEF following the method described by Gulcin et al. [20]. The PEF solution was diluted in methanol and 1 ml of the solution was mixed with DPPH methanolic solution (0.1 mM). The mixture was incubated in a dark condition, at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the mixture was read using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 517 nm. The gallic acid was used as the standard antioxidant and the free radical scavenging activity of the PEF was calculated as follows:

Radical scavenging activity (%) = [(a-b) / (a)] × 100 a= Absorbance of negative control; b= Absorbance of sample

Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP)

The ferric reducing antioxidant power of PEF fraction was evaluated according to the method described by Yen and Chen [21]. Briefly, 1 ml of PEF solution, 2.5 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 2.5 ml of potassium ferricyanide (1 %, w/v) were added to the test tube, and the mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 20 min. In order to stop the reaction, 2.5 ml trichloroacetic acid (10 %, w/v) were added and the mixture was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 min. The upper layer of solution (2.5 ml) was transferred to the test tube containing 2.5 ml of distilled water and 0.5 ml FeCl3 (0.1 %, w/v). The solutions were mixed properly, and the absorbance of the reaction was determined at 700 nm (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) . Gallic acid was used as the reference antioxidant and the ferric reducing antioxidant power of samples was calculated using the following formula.

Antioxidant activity (%) = [(a-b) / (a)] ×100a= Absorbance of negative control; b= Absorbance of sample

Inhibition of ß-carotene bleaching

The ß-carotene bleaching assay was used to determine the antioxidant activity of PEF according to the method described by Ismail et al. [18]. Three milliliter of ß-carotene solution (5 mg ß-carotene/50 ml chloroform), linoleic acid (40 mg) and Tween 20 (400 mg) were mixed thoroughly and then a stream of nitrogen gas was passed to dry the mixture. The ß-carotene-linoleic acid emulsion was prepared by adding 100 ml of ultra-pure water. Then, to 1.5 ml of ß-carotene-linoleic acid emulsion, 20 μl of PEF solution were added and the mixture was incubated in a water bath (50 °C, 60 min). At the end of the incubation, the reacting mixtures were cooled and, the absorbance was read at 470 nm using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The gallic acid was used as the standard in this assay. The following formula was applied to calculate the antioxidant activity of PEF.

Antioxidant activity (%) = [(RDc – RDs) /(RDc)] ×100

RDc= Rate of degradation in the control: [(a/b) /60]; RDs= Rate of degradation in the sample: [(a/b) /60]; a = Initial absorbance of the sample; b = Absorbance after 60 min of incubation

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay (TBARS)

The TBARS assay was used to evaluate the potential of PEF in preventing the oxidation of linoleic acid under oxidative condition, according to the method described by Hendra et al. [22]. The PEF (4 mg) was dissolved in 4 ml of absolute ethanol and then 4.1 ml of 2.5 % linoleic acid in 99 % ethanol, 8 ml of phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7) and 3.9 ml of ultra-pure water were added. The mixture was transferred to the 15 ml screw cap test tube, capped tightly and incubated in a 40 °C oven for 6 days. At the end of the incubation period, 2 ml of sample solutions, aqueous solution of trichloroacetic acid [1 ml of 20 % (w/v)] and aqueous thiobarbituric acid [2 ml, 0.67 % (w/v)] were mixed in a screw cap test glass tube and incubated in boiling water bath for 10 min. The tube was cooled to room temperature and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 20 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was determined using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 532 nm.

The antioxidant activity was reported as:

Percent inhibition = [(a-b) / (a)] × 100 a = Absorbance of the control reaction; b: Absorbance of the sample reaction

Isolation and culture of primary chicken hepatocytes

The chicken hepatocytes were isolated using the 2-step collagenase method as described by Wang et al. [23]. Five-week-old male chickens were treated by intra-peritoneal injection of natrium thiopenthal (45 mg/kg) and heparin (1500 U/kg). The abdominal cavity was opened after full anaesthesia. The liver was perfused with different buffers as described by Wang et al. [23] and then the liver was excised and digested using 0.5 mg/ml of collagenase type IV for 25 min at 37 °C. The William’s E medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) containing 5 % chicken serum and 2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used to stop the digestion. The cells were passed through 100, 60 and 30 μm sieves and subsequently incubated with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and rewashed using William’s E medium containing chicken serum to eliminate the red blood cells. The accuracy of the isolated hepatocytes were confirmed according to morphological characteristics. Cells were cultured in William’s E medium supplemented with 100 U/ml of penicillin-streptomycin, 10 μg/ml insulin and 5 % chicken serum. The cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 in a humidified incubator. The approval of Animal Use and Care Committee (ACUC),, Faulty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University Putra Malaysia for this procedure was obtained.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity effect of PEF on chicken hepatocytes was determined using MTT assay [24]. The cells were grown in each well of 96-well plates with the density of 5 × 103 cells/ 100 μl of the medium. The cells were pre-treated with the serial concentrations of PEF (0, 5, 10, 20, 40 μg/ml) and gallic acid (10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml) as positive control. The cells incubated in a medium devoid of PEF (0 μg/ml) was considered as a negative control. The cells were incubated for 24 h, and then the media were replaced with the fresh media containing 5 μM of AFB1 (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and incubated for another 48 h. Finally, the viability of the cells was determined by using 3–(4,5–Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) assay. The experiment was conducted in triplicates.

Antioxidant enzyme assay

The cells were treated as mentioned earlier in the cytotoxicity assay. Upon treatments, cells were rinsed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) for three times. Then, 6 ml of PBS were added, cells were scraped and transferred into 15 ml centrifuge tube. The cells were centrifuged at 250 × g for 20 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were lysed immediately at 4 °C using 150 μl of lysis buffer (0.5 % Triton x-100, 2 mM ETDA in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5) and then sonicated for 10 s using a sonicator (Hielscher, Teltow, Germany). Then lysates were centrifuged at 2800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected to determine the antioxidant enzymes activity. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione reductase (GR) were determined by using enzyme kits from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China) according to the instructions provided by the kits. The results were expressed as enzyme activity/g protein (U/ g protein) of the cells.

Lipid peroxidation assay

The lipid peroxidation in the chicken hepatocytes was determined by measuring the malondialdehyde (MDA) using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) [25]. The treatments were similar to the cytotoxicity test. Treated cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M) for three times and scraped. The scraped cells were suspended in 4 ml of potassium chloride (1 %) and homogenised using an Ultra-Turrax homogeniser (Wilmington, NC, USA) at 20,000 rpm for 25 s while kept on ice. Then, 300 μl distilled water, 200 μl of homogenised cells, 35 μl of BHT, 165 μl sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and 2 ml TBA were added into the screw cap test tube. The solution was mixed and heated at 90 °C for 60 min. The solution was cooled immediately and 3 ml of n-butanol were added, shaken for 30 s and centrifuged at 2800 × g for 10 min. The absorbance of n-butanol fraction was recorded at 532 nm by a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane was used to construct the standard curve.

Gene expression analyses

The hepatocytes were cultured and treated as mentioned in the cytotoxicity assay. Treated cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.2) for two times and scraped. Total RNA was extracted from cells using a RNasey mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The total RNA was converted to cDNA through reverse transcript PCR technique using Maxime RT Permix kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Sungnam, Korea). The expression of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL1ß), interleukin-6 (IL6), bax, bcl2, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and β-Actin genes (Table 1) were analysed by Real time PCR thermocycler (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). The amplification conditions were optimised for all genes as follows: 95 °C for 5 min (1X), then 95 °C for 20 s, then 58 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 25 s (35X). The expressions of genes were normalised to GAPDH and ß-actin as housekeeping genes according to Vandesompele et al. [26] method using CFX manager software version 2 (Bio-Rad Laboratories). All the real time PCR amplifications were conducted in triplicates.

Table 1.

The primer characteristics used for the gene expression analysis

| Genes | Sequences (5′ to 3′) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NF-kB | F | gaaggaatcgtaccgggaaca | [39] |

| R | ctcagagggccttgtgacagtaa | ||

| iNOS | F | gaacagccagctcatccgata | [40] |

| R | cccaagctcaatgcacaactt | ||

| TNF-α | F | tgtgtatgtgcagcaacccgtagt | [2] |

| R | ggcattgcaatttggacagaagt | ||

| IL1ß | F | tgggcatcaagggctaca | [41] |

| R | tcgggttggttggtgatg | ||

| IL6 | F | caaggtgacggaggaggac | [41] |

| R | tggcgaggagggatttct | ||

| Bax | F | tcctcatcgccatgctcat | [42] |

| R | ccttggtctggaagcagaaga | ||

| Bcl2 | F | gatgaccgagtacctgaacc | [42] |

| R | caggagaaatcgaacaaaggc | ||

| GAPDH | F | gtcagcaatgcatcgtgca | [40] |

| R | ggcatggacagtggtcataaga | ||

| β-Actin | F | acacggtattgtcaccaact | [41] |

| R | taacaccatcaccagagtcc |

Western blot analysis

The expression of 70 kilodalton heat shock protein (Hsp70), caspase-3 and GAPDH proteins were determined by Western blot analysis. The chicken hepatocytes were cultured and treated as described in the cytotoxicity assay. The cells were trypsinised and washed with ice-cold PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2) and the cells were immediately lysed at 4 °C using 150 μl of lysis buffer (0.5 % Triton x-100, 2 mM ETDA in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5) containing 15 μl/ml of protease inhibitor (ProteoBlock Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Fermentas, MD, USA). In order to facilitate the extraction of proteins, the cells were sonicated for 15 s using a sonicator (Hielscher, Teltow, Germany) and incubated on ice for 20 min. In order to collect the supernatant, cell lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 25 min and the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using a Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). The protein (25 μg) was denatured at 95 °C for 5 min and subjected to electrophoresis using Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel. The Hoefer Semi-Dry Transfer Unit was used to transfer the protein to a PVDF membrane, and the membrane was washed using Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). The membrane was incubated in heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) (Biorbyt orb10848), nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) (Biorbyt orb11165), caspase-3 (Biorbyt orb10237) and GAPDH (Thermo Scientific MA1-4711) primary antibodies with dilution rates ranging from 1:500 up to 1:1000 overnight at 4 °C. The PBST (phosphate buffer saline and Tween 20, 0.05 %) was used to wash the membrane for three times. The IRDye 680 Goat Anti-Mouse or IRDye 800 CW Goat Anti-Rabbit secondary antibodies were applied to detect the target proteins by using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA). The intensity of the bands were analysed by the Odyssey software.

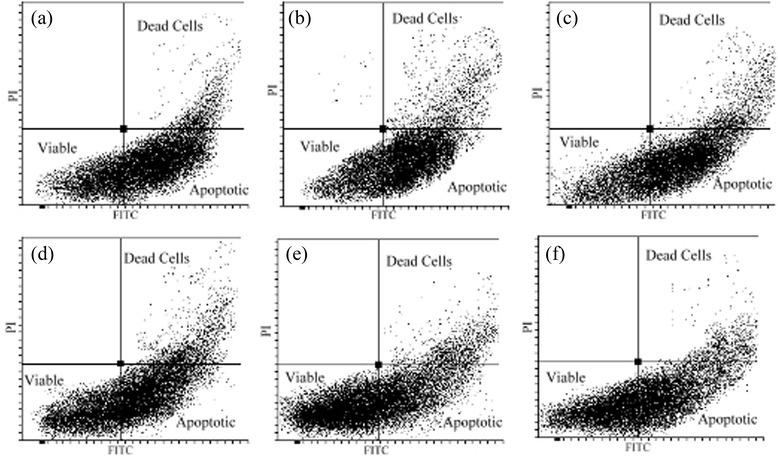

Apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry

The chicken hepatocytes were cultured at the density of 1 × 106 cells per 75 cm2 flask and treated as mentioned in the cytotoxicity test. The cells were trypsinised and washed with ice-cold PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.2). Then, cells were stained using FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The cell apoptosis was evaluated by flow cytometry (FACS-Canto II BD Biosciences) and the data were analysed using Diva software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The characteristics of viable cells were FITC Annexin V and PI negative, whereas early apoptotic cells to be FITC Annexin V positive and PI negative. The cells in late apoptosis or already dead were both FITC Annexin V and PI positive.

Statistical analysis

All the data obtained from this study were analysed in a completely randomised design using the GLM procedure of SAS [27]. The differences between means were determined by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test and considered significant at p < 0.05. All measurements were performed in triplicate samples and carried out independently at least three times.

Results

Extraction yield and total phenolic contents

The yield of PEF was 9.0 ± 0.86 g/100 g dry PKC, and the amount of total phenolics was 658.3 ± 26.32 mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) /g dried PEF (Table 2).

Table 2.

The extraction yield and total phenolic content of phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF)

| Items | PEF |

|---|---|

| Extraction yield (g/100 g DM a) | 9.0 ± 0.86 |

| Total phenolic content b (mg/g DM) | 658.3 ± 26.32 |

All data are presented as means (± S.E.M) of at least three replicates (n = 3)

S.E.M Standard error of the means

aDM: Dry matter

bmg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/g dry matter PEF

Analyses of phenolic compounds by HPLC

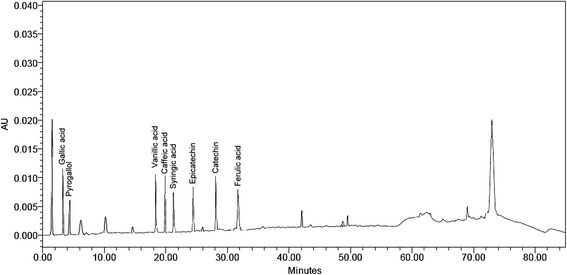

As shown in Fig. 1, the PEF contained phenolic acids, including gallic acid, pyrogallol, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, syringic acid, epicatechin, catechin and ferulic acid with the concentrations ranging from 6.9 to 13.2 mg/g dry fraction (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

The HPLC chromatogram of phenolic acids present in phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF) obtained from PKC detected at 280 nm

Table 3.

The types of phenolic acids detected in phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF)

| Phenolic compounds (mg/g dried PEF) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 12.7 ± 0.12 | Syringic acid | 6.9 ± 0.11 |

| Pyrogallol | 10.0 ± 0.09 | Epicatechin | 7.7 ± 0.07 |

| Vanillic acid | 7.6 ± 0.14 | Catechin | 11.5 ± 0.10 |

| Caffeic acid | 8.1 ± 0.08 | Ferulic acid | 13.2 ± 0.08 |

All data are presented as means (± S.E.M) of at least three replicates (n = 3)

S.E.M Standard error of the means

Antioxidant activity

The IC50 values presented in Table 4 indicated the antioxidant activity of PEF and gallic acid (positive control). The DPPH scavenging activity, reducing power activity, ß-carotene bleaching inhibition and TBARS inhibition values for PEF were 24.6, 31.2, 37.1 and 42.9 μg/ml and these values were significantly (p < 0.05) higher than that of gallic acid with the values of 4.6, 7.4, 11.6 and 14.5 μg/ml, respectively.

Table 4.

The IC50 values indicating antioxidant activity of phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF) and positive control (gallic acid)

| IC50 (μg/ml) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH scavenging activity | Reducing power activity | ß-carotene bleaching inhibition | TBARS inhibition | |

| PEF | 24.6a | 31.2a | 37.1a | 42.9a |

| Gallic acid | 4.6b | 7.4b | 11.6b | 14.5b |

| S.E.M | 0.82 | 0.79 | 1.27 | 1.12 |

All data are presented as means (± SEM) of at least three replicates (n = 3)

Means (n = 3) with different superscripts (a,b) within a column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

S.E.M Standard error of the means

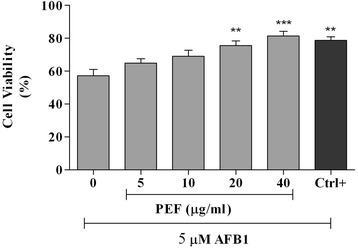

Cytotoxic assay

The cytoprotective activities of PEF and gallic acid against AFB1-cell damage are shown in Fig. 2. The AFB1 at the concentration of 5 μM decreased the cell viability to 57.1 % upon 48 h incubation. Treatment of cells with 20 and 40 μg/ml of PEF enhanced cell viability significantly (p < 0.01). Similarly, gallic acid with the concentration of 10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml significantly (p < 0.01) improved the cell survival.

Fig. 2.

The cytoprotective activity of PEF and gallic acid against AFB1-cell damage. All values are means ± S.E.M of three independent experiments. The cells were pre-treated with different concentrations of PEF and gallic acid as positive control (10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml) for 24 h and then the media were replaced with a medium containing 5 μM of AFB1 and the cells were incubated for another 48 h. The experiment was performed in triplicate. ***p < 0.001 and **p < 0.01 indicated significant difference compared to the untreated control (0)

Antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation

Table 5 shows the results of total protein, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes activity in chicken hepatocytes. It was observed that with the increase in the concentration of PEF, the total cellular protein increased from 0.6 mg/ml to 0.8 mg/ml. The lipid peroxidation values were reduced gradually from 7.5 to 3.8 nM MDA/mg protein. The activities of SOD, CAT and GR were 4.2, 3.8 and 0.2 U/mg protein, respectively, without the addition of PEF, but increased to 7.8, 6.9 and 0.5 U/mg protein, respectively, when cells were treated with 40 μg/ml of PEF. In general, the concentrations of 20 and 40 μg/ml of PEF significantly (p < 0.05) improved the oxidative activities of biomarkers, indicating the potential of the PEF to alleviate the negative impacts of AFB1 on hepatocytes functions. Furthermore, these concentrations of PEF exhibited comparable results to that of gallic acid as a reference antioxidant used in this study.

Table 5.

The total protein, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activity of chicken hepatocytes pretreated with phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF) and exposed to AFB1

| Items | AFB1 (5 μM) | S.E.M | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEF (μg/ml) | Control+ | ||||||

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 40 | |||

| Total protein (mg ml−1) | 0.6b | 0.6b | 0.6b | 0.8a | 0.8a | 0.8a | 0.02 |

| Lipid peroxidation (nM MDA mg−1 protein) | 7.5a | 6.9ab | 5.6c | 4.3d | 3. 8de | 4.6d | 0.46 |

| SOD activity (U mg−1 protein) | 4.2d | 4.8cd | 5.7bc | 6.3b | 7.8a | 6.7ab | 0.8 |

| CAT activity (U mg−1 protein) | 3.8de | 4.2d | 4.9bcd | 5.7b | 6.9a | 5.5bc | 0.47 |

| GR activity (U mg−1 protein) | 0.2c | 0.2c | 0.4b | 0.5a | 0.5a | 0.5a | 0.06 |

All cells were pre-treated with different concentrations of PEF for 24 h, then the media were replaced with a medium containing 5 μM of AFB1 and the cells were incubated for another 48 h

MDA Malondialdehyde as lipid peroxidation biomarker

Control+: 10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml gallic acid

SOD Superoxide dismutase

CAT Catalase

GR Glutathione reductase

S.E.M Standard error of the means

Means (n = 3) with different superscripts (a,b,c,d,e) within a row are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Changes in molecular biomarkers of oxidative stress

The changes in the expression of various genes in chicken hepatocytes are presented in Table 6. The gradual increase in PEF concentration up-regulated the anti-apoptosis gene (bcl2) and down-regulated the expressions of NF-kB, proinflammatory mediators (iNOS, TNF-α, IL1ß and IL6) and pro-apoptotic gene (bax). The PEF at 40 μg/ml produced comparable results to gallic acid as a positive control.

Table 6.

The changes in the expression of different genes in chicken hepatocytes pretreated with phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF) and exposed to AFB1

| Gene expression (Fold changes) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | PEF concentration (μg/ml) | Control+ | S.E.M | ||||

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 40 | |||

| Up-regulated genes | |||||||

| Bcl2 | 1.0d | +2.1cd | +3.2c | +4.3b | +5.9a | +5.6a | 0.39 |

| Down-regulated genes | |||||||

| NF-kB | 1.0d | −1.5d | −2.6c | −3.6b | −4.4a | −4.6a | 0.36 |

| TNF-α | 1.0d | −1.2cd | −2.1c | −3.7b | −5.1a | −4.9a | 0.41 |

| IL1ß | 1.0d | −1.1d | −1.6c | −2.2b | −2.9a | −3.2a | 0.18 |

| IL6 | 1.0d | −1.3cd | −1.7c | −2.4b | −3.5a | −3.4a | 0.21 |

| iNOS | 1.0d | −1.7cd | −2.4bc | −3.3b | −4.8a | −4.4a | 0.43 |

| Bax | 1.0d | −1.8cd | −2.7c | −4.2b | −5.7a | −5.2a | 0.47 |

The cells were pre-treated for 24 h with different concentrations of PEF ranging from 0 to 40 μg/ml and positive control (10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml gallic acid). The media were replaced with a medium containing 5 μM of AFB1 and the cells were incubated for another 48 h

The expression of each gene was normalised to the GAPDH and ß-actin expressions as housekeeping genes and then the result normalised to the expression of that gene in the negative control (PEF 0 μg/ml)

S.E.M Standard error of the means

Means (n = 3) with different superscripts (a,b,c,d) within a row are significantly different (p < 0.05)

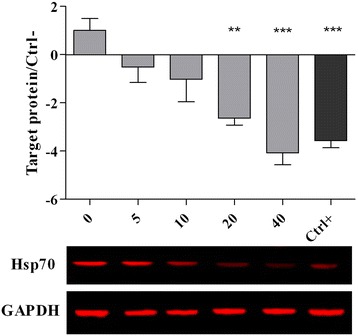

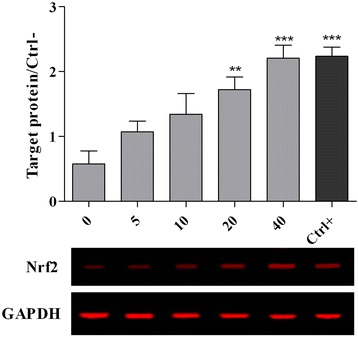

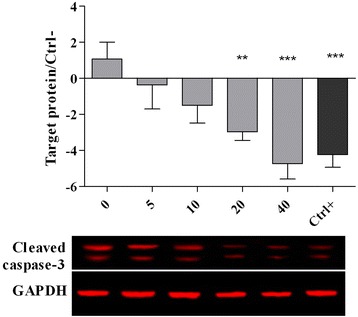

The western blot analysis confirmed the changes in the expression of Hsp70 (Fig. 3), nrf2 (Fig. 4) and caspase-3 (Fig. 5) proteins. It was observed that the high concentrations of PEF (20 and 40 μg/ml) significantly (p < 0.05) down-regulated the Hsp70 and caspase-3 proteins while up-regulated the nrf2 protein as compared to the cells without PEF pretreatment (0 μg/ml). The gallic acid has also been found to down-regulate the Hsp70 and caspase-3 proteins and up-regulate the nrf2 protein.

Fig. 3.

Expression of Hsp70 protein in chicken hepatocytes. The cells were pre-treated for 24 h with different concentrations of PEF ranging from 0 to 40 μg/ml and positive control (gallic acid, 10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml). The media were replaced with a medium containing 5 μM of AFB1 and the cells were incubated for another 48 h. All values represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. *** p < 0.001 and ** p < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared to the untreated control (0)

Fig. 4.

Expression of nrf2 protein in chicken hepatocytes. The cells were pre-treated for 24 h with different concentrations of PEF ranging from 0 to 40 μg/ml and positive control (gallic acid, 10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml). The media were replaced with a medium containing 5 μM of AFB1 and the cells were incubated for another 48 h. All values represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. *** p < 0.001 and ** p < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared to the untreated control (0)

Fig. 5.

Expression of caspase-3 protein in chicken hepatocytes. The cells were pre-treated for 24 h with different concentrations of PEF ranging from 0 to 40 μg/ml and positive control (gallic acid, 10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml). The media were replaced with a medium containing 5 μM of AFB1 and the cells incubated for another 48 h. All values represent mean ± standard error from three independent experiments. *** p < 0.001 and ** p < 0.01 indicate significant difference compared to the untreated control

Apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry

The flow cytometry analysis plots are presented in Fig. 6. As observed in Fig. 6-a, the majority of cells showed apoptosis. However, it was evident that the increase in the concentration of PEF resulted in the decrease of the population of apoptotic cells (Fig. 6–b to -e). Similarly, Fig. 6–f indicates that pretreatment of cells with the gallic acid decreased the apoptotic cells. The percentage values for the viable, apoptotic and dead cells obtained from flow cytometry analysis are presented in Table 7. In the medium without PEF (0 μg/ml), the majority of the cell mass (52.8 %) were recognised as apoptotic cells. The increasing concentrations of PEF reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells and enhanced the cell viability significantly (p < 0.05). The percentage of apoptotic and viable cells in hepatocytes treated with gallic acid as a positive control were 41.1 and 40.2 %, respectively, which were comparable to that of hepatocytes treated with 20 and 40 μg/ml of PEF.

Fig. 6.

Flow cytometry analyses of chicken hepatocytes pretreated with phenolic-enriched fraction (PEF) and exposed to 5 μM of AFB1. The a, b, c, d and e showed cells pretreated with 0, 5, 10, 20 and 40 μg/ml of PEF, respectively. The f indicated that the cells were pretreated with gallic acid at the concentration of 10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml

Table 7.

Percentage of viable, apoptotic and dead cells analysed by flow cytometry

| Cells (%) | PEF (μg/ml) | Control+ | S.E.M | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 40 | |||

| Viable | 15.2d | 16.2d | 27.3c | 36.1b | 46.2a | 40.2ab | 3.2 |

| Apoptotic | 52.8a | 54.1a | 48.4b | 43.4bc | 37.1d | 41.1cd | 2.4 |

| Dead | 32.1a | 29.8a | 24.3b | 20.7bc | 16.9d | 18.8cd | 2.1 |

The cells were pre-treated with different concentrations of PEF for 24 h, then the media were replaced with a medium containing 5 μM of AFB1 and the cells were incubated for another 48 h

A minimum of 15,000 cells per sample was analysed by flow cytometry

Control+: 10 μM or 1.7 μg/ml gallic acid

Means with different superscripts (a,b,c,d) within a row are significantly different (p < 0.05)

PEF Phenolic-enriched fraction

S.E.M Standard error of the means

Discussion

The types of phenolic compounds detected in PEF were slightly different from that of the oil palm fruit extract which showed the presence of protocatechuic, p-hydroxybenzoic and p-coumaric acids, besides gallic, vanillic, caffeic, syringic and ferulic acids [28]. Tan et al. [29] also reported the presence of p-hydroxybenzoic acid, cinnamic acid, ferulic acid and coumaric acid in the oil, while, Jaffri et al. [30] observed the presence of catechin derivatives in the oil palm leaf extract. It seemed that the PEF contained additional types of phenolic compounds as compared to those detected in the oil and leaf extracts. However, the types of phenolic compounds present are subjected to numerous factors including extraction, detection and identification procedures, besides other agronomic factors. Phenolic compounds have been reported as a potential antioxidant [31, 32], thereby PEF can be considered a reliable source of natural antioxidants for protecting cells against xenobiotics toxicity.

The results presented in Table 5 and Fig. 2 revealed that, pretreatment of hepatocytes with different concentrations of PEF improved the lipid peroxidation and cellular antioxidant enzymes, concomitant with the increase in cell viability when cells were exposed to AFB1. These findings reflected the cytoprotective properties of PEF, which could be attributed to its antioxidant activity. Previous studies have confirmed the ability of mycotoxins to impair the balance between pro-oxidants and antioxidants in the cells, which resulted in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), that led to lipoperoxidation and oxidative stress [3–7, 9, 12]. Consequently, it was emphasized that antioxidant enzymes would function as the main defense mechanism against the ROS in the cells. In the present study, the PEF exerted cytoprotective effect which reduced the toxic symptoms of AFB1 probably through activation of antioxidant enzymes and inhibition of lipid peroxidation chain reaction. Similar studies have reported the role of natural antioxidants in enhancing antioxidant enzymes, inhibiting lipid peroxidation and alleviating oxidative stress in cells exposed to mycotoxins [6, 33–35]. The PEF at 40 μg/ml showed cytoprotection activity and alleviation of oxidative biomarkers reaching up to that of gallic acid at 1.7 μg/ml. Although the concentrations of phenolic compounds used in the assay differ, the PEF should be considered effective in alleviating the AFB1 effects. These findings should be of interest in lieu of PEF source and availability.

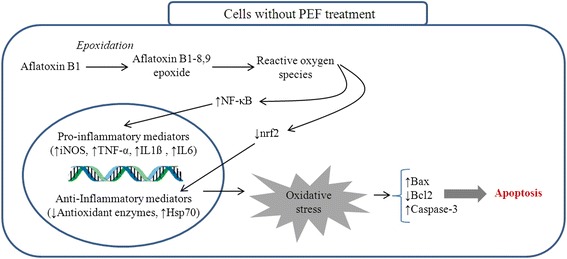

Table 6 and Figs. 3, 4 and 5 show the expression of molecular biomarkers involved in oxidative stress, inflammatory response and apoptosis in cells pretreated with various concentrations of PEF and exposed to AFB1. The relationship between expressions of genes and proteins provides a better understanding of the mechanism of action of PEF against AFB1-cell damage. As shown in Fig. 7, the AFB1 was converted to the Aflatoxin B1–8,9 epoxide through epoxidation and this active form initiated the production of ROS in the cells. Thereafter, the excessive amount of ROS elicited the NF-kB up-regulation and nrf2 down-regulation. The NF-kB upon up-regulation induced the expression of various pro-inflammatory mediators, including iNOS, TNF-α, IL1ß and IL6 (Fig. 7). The nrf2 as the redox-sensitive transcription factor could activate the cellular antioxidant defense mechanism and enhance the production of antioxidant enzymes and heat shock proteins [36]. The down-regulation of nrf2 reduced the antioxidant enzymes production and increased the up-regulation of Hsp70 (Fig. 7). The Hsp70 plays a role as a sensor of cellular redox changes acting like antioxidant enzymes. For instance, under oxidative stress the intracellular components, particularly proteins could undergo oxidation. The Hsp70 restores and maintains the redox homeostasis of the cells even under oxidative stress [36].

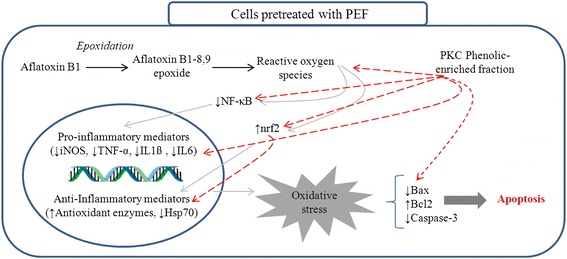

Fig. 7.

This diagram illustrates the events taking place in un-treated chicken hepatocytes exposed to AFB1

The up-regulation of pro-inflammatory mediators accompanied by suppression of anti-inflammatory proteins disrupted the cell homeostasis leading to an imbalance between anti-apoptotic (bcl2) and pro-apoptotic (bax and caspase-3) effectors. The imbalance between anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic effectors induced apoptosis and cell death (Fig. 7). The pretreatment of cells with PEF induced the cells to attenuate the expression of NF-kB and subsequently pro-inflammatory mediators (iNOS, TNF-α, IL1ß and IL6) (Fig. 8). This is possibly due to the direct inhibition of ROS together with modulation of NF-kB expression. On the other hand, the suppression of pro-inflammatory mediators through direct action of PEF could be another plausible reason (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

This diagram illustrates the probable protective mechanisms of PEF in chicken hepatocytes exposed to AFB1

The PEF up-regulated the expression of nrf2 and its activation enhanced the antioxidant enzymes production (Table 5), while inhibiting the Hsp70 expression. The inverse relationship between antioxidant enzymes and Hsp70 protein suggests that the antioxidant enzymes regulate the cellular redox homeostasis in lieu of Hsp70 protein, thereby high expression of Hsp70 is no longer required. In line with this result, Costa et al. [37] also reported the critical role of phenolic compounds in up-regulation of nrf2 protein and enhancement of antioxidant enzymes production.

The results of the present study showed that, the PEF not only affected the NF-kB and nrf2 expressions, but also regulated the imbalance between anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic effectors resulting in the enhancement of cell survival. The anti-apoptotic activity of PEF was probably due to the presence of phenolic compounds (gallic acid, pyrogallol, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, syringic acid, epicatechin, catechin and ferulic acid) which up-regulated the bcl2 gene and down-regulated the bax gene and caspase-3 protein (Fig. 8, Table 6). Similarly, several observations demonstrated the close relationship between antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds with cellular antioxidant enzymes activity and reduction of apoptosis cell death in various animal and human cell lines [5, 11, 38].

Conclusions

The present study showed that PEF could be considered as a cytoprotective agent by up-regulating the antioxidant-related genes and down-regulating the pro-inflammatory and apoptosis associated genes in hepatocytes exposed to AFB1. The findings valorised the phenolic compounds of PKC and paved the way for production of an alternative cytoprotective agent against AFB1 cytotoxicity.

Acknowledgment

The research funds provided by the Ministry of Education, Malaysia, under the Long-Term Research Grant Scheme (LRGS), Project number: UPM/700-1/3/LRGS is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- PKC

Palm kernel cake

- AFB1

Aflatoxin B1

- PEF

Phenolic-enriched fraction

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TPC

Total phenolic content

- GAE

Gallic acid equivalent

- DPPH

1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazil

- ACUC

Animal Use and Care Committee

- MTT

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- CAT

Catalase

- GR

Glutathione reductase

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- TBARS

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulphate

- NF-kB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- iNOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- IL1ß

Interleukin-1 beta

- IL6

Interleukin-6

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- Hsp70

70 kilodalton heat shock protein

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The contributions of authors are as follow: Conception and design of experiment: EO, NA, IZ and YMG. Conduction of experiments: EO, ME, MS, AO and EK. Data acquisition and statistical analysis: EO, ME, MS, AO and EK. Manuscript preparation: EO, ME and NA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ehsan Oskoueian, Email: ehs424@yahoo.com.

Norhani Abdullah, Phone: +60389461147, Email: norhani.biotech@gmail.com.

Idrus Zulkifli, Email: zulkifli@upm.edu.my.

Mahdi Ebrahimi, Email: mehdiebrahimii@gmail.com.

Ehsan Karimi, Email: ehsan_b_Karimi@yahoo.com.

Yong Meng Goh, Email: ymgoh@upm.edu.my.

Armin Oskoueian, Email: armin_oskoueian@yahoo.com.

Majid Shakeri, Email: majidmarch@live.com.my.

References

- 1.Rawal S, Kim JE, Coulombe R., Jr Aflatoxin B1 in poultry: Toxicology, metabolism and prevention. Res Vet Sci. 2010;89:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He Y, Fang J, Peng X, Cui H, Zuo Z, Deng J, et al. Effects of sodium selenite on aflatoxin B1-induced decrease of ileac T cell and the mRNA contents of IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-α in broilers. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;159:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-9999-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdel-Aziem S, Hassan A, El-Denshary E, Hamzawy M, Mannaa F, Abdel-Wahhab M. Ameliorative effects of thyme and calendula extracts alone or in combination against aflatoxins-induced oxidative stress and genotoxicity in rat liver. Cytotechnology. 2014;66:457–470. doi: 10.1007/s10616-013-9598-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Nekeety AA, Mohamed SR, Hathout AS, Hassan NS, Aly SE, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Antioxidant properties of Thymus vulgaris oil against aflatoxin-induce oxidative stress in male rats. Toxicon. 2011;57:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan AM, Abdel-Aziem SH, El-Nekeety AA, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Panax ginseng extract modulates oxidative stress, DNA fragmentation and up-regulate gene expression in rats sub chronically treated with aflatoxin B1 and fumonisin B1. Cytotechnol 2015;67(5):861-71. doi:10.1007/s10616-014-9726-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.El-Nekeety AA, Abdel-Azeim SH, Hassan AM, Hassan NS, Aly SE, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Quercetin inhibits the cytotoxicity and oxidative stress in liver of rats fed aflatoxin-contaminated diet. Toxicol Rep. 2014;1:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyki M, Zhaveh S, Khalili ST, Rahmani-Cherati T, Abollahi A, Bayat M, et al. Encapsulation of Mentha piperita essential oils in chitosan–cinnamic acid nanogel with enhanced antimicrobial activity against Aspergillus flavus. Ind Crop Prod. 2014;54:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tedesco D, Steidler S, Galletti S, Tameni M, Sonzogni O, Ravarotto L. Efficacy of silymarin-phospholipid complex in reducing the toxicity of aflatoxin B1 in broiler chicks. Poultry Sci. 2004;83:1839–1843. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.11.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renzulli C, Galvano F, Pierdomenico L, Speroni E, Guerra M. Effects of rosmarinic acid against aflatoxin B1 and ochratoxin‐A‐induced cell damage in a human hepatoma cell line (Hep G2) J Appl Toxicol. 2004;24:289–296. doi: 10.1002/jat.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa S, Utan A, Speroni E, Cervellati R, Piva G, Prandini A, et al. Carnosic acid from rosemary extracts: a potential chemoprotective agent against aflatoxin B1: An in vitro study. J Appl Toxicol. 2007;27:152–159. doi: 10.1002/jat.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa S, Utan A, Cervellati R, Speroni E, Guerra MC. Catechins: natural free-radical scavengers against ochratoxin A-induced cell damage in a pig kidney cell line (LLC-PK1) Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1910–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braicu C, Rugina D, Chedea VS, Tudoran O, Balacescu O, Neagoe I, et al. Protective action of different natural flavan-3-ols against aflatoxin B1-related cytotoxicity. J Food Biochem. 2010;34:595–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2010.00350.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nones J, Nones J, Trentin AG. Flavonoid hesperidin protects neural crest cells from death caused by aflatoxin B1. Cell Biol Int. 2013;37(2):181–186. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambanthamurthi R, Tan Y, Sundram K, Abeywardena M, Sambandan T, Rha C, et al. Oil palm vegetation liquor: a new source of phenolic bioactives. Brit J Nutr. 2011;106:1655–1663. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511002121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aladetuyi A, Olatunji GA, Ogunniyi DS, Odetoye TE, Oguntoye SO. Production and characterization of biodiesel using palm kernel oil; fresh and recovered from spent bleaching earth. Biofuel Res J. 2014;1:134–138. doi: 10.18331/BRJ2015.1.4.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ofori-Boateng C, Lee K. Sustainable utilization of oil palm wastes for bioactive phytochemicals for the benefit of the oil palm and nutraceutical industries. Phytochem Rev. 2013;12:173–190. doi: 10.1007/s11101-013-9270-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crozier A, Jensen E, Lean M, McDonald M. Quantitative analysis of flavonoids by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 1997;761:315–321. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(96)00826-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ismail HI, Chan KW, Mariod AA, Ismail M. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of cantaloupe (Cucumis melo) methanolic extracts. Food Chem. 2010;119:643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karimi E, Oskoueian E, Hendra R, Jaafar HZ. Evaluation of Crocus sativus L. stigma phenolic and flavonoid compounds and its antioxidant activity. Molecules. 2010;15:6244–6256. doi: 10.3390/molecules15096244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulcin l, Gungor Sat I, Beydemir S, Elmastas M, Irfan Kufrevioglu O. Comparison of antioxidant activity of clove (Eugenia caryophylata Thunb) buds and lavender (Lavandula stoechas L.). Food Chem. 2004;87:393-400.

- 21.Yen G, Chen H. Antioxidant activity of various tea extracts in relation to their antimutagenicity. J Agr Food Chem. 1995;43:27–32. doi: 10.1021/jf00049a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendra R, Ahmad S, Oskoueian E, Sukari A, Shukor MY. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxicity of Phaleria macrocarpa (Boerl.) Scheff Fruit. BMC Complem Altern M. 2011;11:110–118. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang XG, Shao F, Wang HJ, Yang L, Yu JF, Gong DQ, et al. MicroRNA-126 expression is decreased in cultured primary chicken hepatocytes and targets the sprouty-related EVH1 domain containing 1 mRNA. Poultry Sci. 2013;92:1888–1896. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-02919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang S, Lv Y, Chen H, Adam A, Cheng Y, Hartung J, et al. Comparative analysis of αB-crystallin expression in heat-stressed myocardial cells in vivo and in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pareek A, Godavarthi A, Issarani R, Nagori BP. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activity of Fagonia schweinfurthii (Hadidi) Hadidi extract in carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in HepG2 cell line and rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150:973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3(7):1–11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: A practical guide. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neo YP, Ariffin A, Tan CP, Tan YA. Determination of oil palm fruit phenolic compounds and their antioxidant activities using spectrophotometric methods. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2008;43(10):1832–1837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2008.01717.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan YA, Sambanthamurthi R, Sundram K, Wahid MB. Valorisation of palm by-products as functional components. Eur J Lipid Sci Tech. 2007;109(4):380–393. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200600251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaffri JM, Mohamed S, Rohimi N, Ahmad IN, Noordin MM, Manap YA. Antihypertensive and cardiovascular effects of catechin-rich oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) leaf extract in nitric oxide–deficient rats. J Med Food. 2011;14:775–783. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karimi E, Mehrabanjoubani P, Keshavarzian M, Oskoueian E, Jaafar HZ, Abdolzadeh A. Identification and quantification of phenolic and flavoind components in straw and seed husk of some rice varieties (Oryza sativa L.) and their antioxidant properties. J Sci Food Agr. 2014;94(11):1–7. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oskoueian E, Abdullah N, Saad WZ, Omar AR, Ahmad S, Kuan WB, et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of methanolic extracts from Jatropha curcas Linn. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang A, Sun H, Wang X. Recent advances in natural products from plants for treatment of liver diseases. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;63:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou YJ, Zhao YY, Xiong B, Cui XS, Kim NH, Xu YX, et al. Mycotoxin-containing diet causes oxidative stress in the mouse. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hassan NS, Abdel-Wahhab KG, Khadrawy YA, El-Nekeety AA, Mannaa FA, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Evaluation of radical scavenging properties and the protective role of papaya fruits extracts against oxidative stress in rats fed aflatoxin-contaminated diet. Com Sci. 2013;4:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Golli-Bennour E, Bacha H. Hsp70 expression as biomarkers of oxidative stress: Mycotoxins’ exploration. Toxicology. 2011;287:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa S, Schwaiger S, Cervellati R, Stuppner H, Speroni E, Guerra MC. In vitro evaluation of the chemoprotective action mechanisms of leontopodic acid against aflatoxin B1 and deoxynivalenol-induced cell damage. J Appl Toxicol. 2009;29:7–14. doi: 10.1002/jat.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khanduja KL, Avti PK, Kumar S, Mittal N, Sohi KK, Pathak CM. Anti-apoptotic activity of caffeic acid, ellagic acid and ferulic acid in normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: a Bcl-2 independent mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760(2):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou X, Liu F. Polyphenol extracts from Punica granatum and Terminalia chebula are anti-inflammatory and increase the survival rate of chickens challenged with Escherichia coli. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37(10):1575–1582. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b14-00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carvajal BG, Methner U, Pieper J, Berndt A. Effects of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis on cellular recruitment and cytokine gene expression in caecum of vaccinated chickens. Vaccine. 2008;26:5423–5433. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan Z, Fang Q, Geng S, Kang X, Cong Q, Jiao X. Analysis of immune-related gene expression in chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells following Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis infection in vitro. Res Vet Sci. 2012;93:716–720. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu B, Cui H, Peng X, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng J, et al. Dietary nickel chloride induces oxidative stress, apoptosis and alters Bax/Bcl-2 and caspase-3 mRNA expression in the cecal tonsil of broilers. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;63:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]