Abstract

Objective

To determine whether personality disorders diagnosed during a depressive episode have long-term outcomes more typical of other patients with personality disorders or of patients with non-comorbid major depression.

Method

The study used six year outcome data collected from the multisite Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS). Diagnoses and personality measures gathered from the study cohort at the index assessment using interview and self-report methods were associated with symptomatic, functional, and personality measures at six year follow-up. 668 patients were initially recruited to the CLPS study, of whom 522 were successfully followed for six years. All individuals had a DSM-IV diagnosis of one of four personality disorders (PD: Borderline, Schizotypal, Obsessive-Compulsive, or Avoidant) or had a DSM-IV diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) with no accompanying personality disorder.

Results

Results demonstrated that the group of patients with comorbid PD/MDD at the index evaluation had six year outcomes similar to patients with pure PD, and significantly worse than those of patients with pure MDD. Stability estimates of personality traits were similar for PD patients with and without MDD at the index evaluation.

Conclusions

The long term outcome of patients diagnoses with comorbid PD/MDD appears similar to those with pure PD and is significantly worse than those with pure MDD, suggesting that PD diagnoses established during depressive episodes are valid reflects of personality pathology rather than an artifact of depressive mood.

For years, investigators have expressed concern about the validity of assessments of personality traits and personality disorder within the context of a depressive episode. These concerns result from initial studies that demonstrated that successful treatments of major depressive disorder can lead to changes in measures of personality and personality disorder (1–4). For example, a seminal study by Hirschfeld et al.(1) found that certain personality traits such as emotional strength, dependency, and extraversion changed significantly more at one year follow-up in treated depressed patients who had recovered than in depressed patients who had not recovered. Such results have led some investigators to conclude that personality assessments of symptomatic depressed patients may not accurately reflect their trait characteristics before, between, or after depressive episodes. (5,6) Thus, assessing personality traits and related problems during a depressive episode could lead to overdiagnosis of personality disorder and perhaps to unwarranted conclusions about prognosis, given that comorbid personality disorder is generally considered a risk factor for poorer outcome (7–10, but see also Mulder,11). As a result, some have recommended considering adjusting for current mood when assessing personality (6).

However, a number of research findings temper the conclusion that a depressive episode necessarily leads to overdiagnosis of personality disorder. First, instructional sets that focus upon differentiating long-term characteristics from current state during the assessment may reduce or eliminate emotional state effects, either in self-report or interview assessments.(12,13) Second, some studies that have demonstrated marked state effects on personality measures utilized instruments saturated with psychopathology as opposed to personality traits, such as the MMPI or MCMI.(1–3) Third, most studies suggesting mood effects on personality have done so in the context of demonstrating changes in personality associated with the treatment of depression.(2,4,14) However, as Fava et al. (15) have observed, it is also possible that these antidepressant treatments affect a range of characteristics beyond depression, and that some of these nonspecific treatment effects may also lead to changes in personality problems.

Fourth, evidence suggests that the personality self-descriptions offered by depressed patients typically converge with descriptions provided by family informants (16), whose judgments are presumably unaffected by the patient’s mood state. Fifth, the duration of many previous studies is typically limited to that of a brief clinical trial, which may be too short to distinguish enduring from transitory personality change. Finally, many studies focus exclusively upon personality changes in depressed patients (14), without providing a non-depressed comparison group to gauge whether any observed changes in personality reflect variability beyond changes that might be expected in individuals without mood disorders.

This study examines the hypothesis that presence of a Major Depressive Episode will lead to (a) overidentification of problematic personality traits that fail to persist over the long term, and (b) lower stability in normative personality traits over the long term. These questions are addressed by examining personality changes in (a) patients experiencing a major depressive episode who lack significant personality pathology; (b) patients experiencing a major depressive episode who have significant comorbid personality pathology; and (c) patients not experiencing a depressive episode but who have significant personality pathology. The present study is unique in examining long term outcome in patients presenting with depression who differ markedly in their initial presentation of personality pathology. If indeed a major depressive episode seriously confounds assessment of personality and personality disorder, then patients who present with comorbid depression and personality disorder might be expected to have long-term outcomes more similar to those of “pure” depressed patients than to “pure” personality disorder patients. Furthermore, one would expect that long term personality trait stability should be appreciably lower in both groups with depression than in those with personality disorders only. However, if these predictions do not hold and comorbid patients resemble “pure” personality disorder patients more than “pure” depression over the long term, these results would indicate that personality and personality disorder can be successfully identified during a major depressive episode.

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were drawn from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Study (CLPS: 17), a multi-site, prospective, naturalistic, longitudinal study. Recruitment aimed to obtain a diverse, representative sample from in- and outpatient clinical programs affiliated with four recruitment sites (Brown, Columbia, Harvard, and Yale). CLPS enrolled 668 participants aged 18 to 45 with at least one of four personality disorders, or with current depression without any personality disorder. CLPS focused on recruiting four specific personality diagnoses (schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive compulsive personality disorders), selected because of their prevalence and research base in clinical samples and to span the three DSM-IV clusters. Of the 668 participants in CLPS, 573 met criteria for a personality disorder study group and 95 for the Major Depressive Disorder (without personality disorder) group. Detailed descriptions of the CLPS methods and characteristics of the overall study group have been previously reported (17), including specific co-occurrence patterns among the Axis I psychiatric and Axis II personality diagnoses in this study (18). There was extensive comorbidity of major depression and personality disorder, a finding that echoes those reported for other clinical samples (19), and most participants received a variety of different treatments over the course of the study (20).

The current report focuses upon membership in one of three study groups. Patients were assigned to the “Depression Only” group if they met criteria for a major depressive episode, were at least 2 criteria below the diagnostic threshold for all specific personality disorders, and met fewer than 15 total personality disorder criteria at baseline assessment. Thus, in contrast to most previous studies of this issue, this group constitutes a “pure” depressed group with respect to personality pathology. Participants were assigned to the “Personality Disorder Only” group if they met criteria for a DSM-IV personality disorder at the baseline assessment but did not meet criteria for a major depressive episode. Finally, patients were assigned to the “Personality Disorder+Major Depression” group if they met criteria for both a personality disorder and a major depressive episode at baseline assessment. Patients who met criteria for a personality disorder and who had a lifetime diagnosis of major depression but were in remission at baseline were not included in the study to control for any artifacts associated with depression relapse.

Assessment Protocol

At baseline, an interviewer administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Patient Version (21) to assess Axis I psychiatric disorders and the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (22) to assess personality disorders. Participants were re-interviewed after 6 and 12 months, and then yearly thereafter for six years following baseline assessment. At six years, a comprehensive evaluation was completed that included the DIPD-IV as well as self-report measures described below. A total of 522 (78%) of the original 668 study participants participated in the year six follow-up evaluation: 119 were assigned to the Personality Disorder Only group, 73 to the Depression Only group, and 241 to the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group. The proportion of completers vs. study noncompleters did not differ among the three study groups (χ2(2) = 0.74, n.s.).

As noted in a previous report (23), the four personality disorders targeted in this study demonstrated comparable stability across the six year interval studied here (Year 6 estimated stability in men: schizotypal=.57, borderline=.53, avoidant=.57, obsessive-compulsive=.37; in women: schizotypal=.61, borderline=.46, avoidant=.59, obsessive-compulsive=.52). Also, among those patients diagnosed with personality disorders, there were no differences between the four study personality disorder diagnoses in comorbid depression status (χ2(3) = 0.84, n.s.); for schizotypal, 63.2% presented with concurrent depression, with comparable numbers for borderline (65.5%), avoidant (69.4%), and obsessive-compulsive (68.7%) personality disorders.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Patient Version (SCID-I/P)

The SCID-I/P was administered at baseline. Kappa coefficients (24) for inter-rater reliability for psychiatric diagnoses ranged from .57 to 1.0; kappa was 0.80 for Major Depression and 0.76 for dysthymic disorder (25).

Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (22)

This semi-structured diagnostic interview to assess DSM-IV personality disorders requires that criteria be pervasive for at least two years and characteristic of the person for most of his or her adult life. Inter-rater reliability kappa coefficients for diagnoses ranged from .58 to 1.0 (25). Test-retest reliability kappa coefficients ranged from .69 (borderline) to .74 (obsessive-compulsive) (25). In the present study, the total number of DSM-IV personality disorder criteria coded as present and clinically significant was used as an indicator of global personality pathology. In the present study, reliability at baseline for the total personality disorder criteria count as estimated by coefficient alpha was .95, and at six-year follow-up coefficient alpha for the personality disorder criteria count was also .95.

NEO Personality Inventory, Revised (NEO-PI-R)

The NEO-PI-R (26) was designed to comprehensively assess the five dimensions of the Five-Factor Model (27) of personality. Extensive research has suggested that these factors, described as Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to Experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness, can be universally identified and explain much of the variation in normal personality. The NEO-PI-R scales are normed using T-scores, where 50T represents the average of a community sample and 10T represents the standard deviation in that sample. Internal consistency reliabilities for the five domains in this sample at the baseline assessment ranged from .87 to .92.

Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Examination (LIFE: 28)

The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Examination is a structured interview that measures, among other variables, the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale that constitutes Axis V of the DSM-IV. The GAF scale is a commonly used clinician-rated single item ranging from 1–100, with higher scores indicating better overall adjustment and higher levels of functioning.

Personality Assessment Inventory Depression Scale

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Depression (DEP) scale of the Personality Assessment Inventory (29). The Personality Assessment Inventory is a broad-ranging clinical assessment that contains 11 clinical scales, one of which is the 24-item DEP scale, a dimensional measure of depressive symptomatology divided into three subscales reflecting different aspects of depressive symptoms: Cognitive, Affective, and Physiological. As with the NEO-PI-R, the Depression scale and subscales are normed using T-scores. The reliability and validity of the Depression scale and subscales with respect to other commonly used marked of depressive symptomatology have been extensively documented (29). In the present study, reliability at six-year follow-up as estimated by coefficient alpha was .94 for the Depression full scale and .87, .92, and .77 for Cognitive, Affective, and Physiological subscales, respectively. The Depression scale was not administered at baseline.

Data Analyses

One-way analyses of variance, followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests, were used to compare differences at six-year follow-up among the three study groups with respect to degree of personality pathology and depressive symptomatology, extremity of personality traits, and absolute value of changes observed on personality trait measures between baseline and year six assessments. Pearson correlations were computed to compare the three study groups on the stability of personality trait and pathology measures over the six year study interval, with significance of differences among these stability estimates tested using a z-test of comparisons between independent correlations.

Results

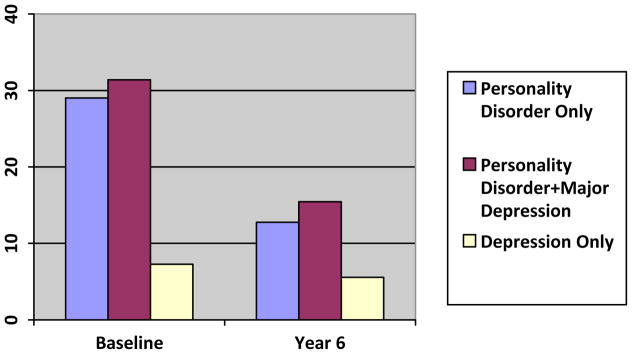

Table 1 summarizes differences among the three study groups over the course of the study. As expected given the construction of the study groups, there were large differences at baseline in the number of personality disorder symptoms present between the Depression Only group and the two personality disorder groups. There were no differences at baseline between the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group and the Personality Disorder Only group in degree of expressed personality pathology, with virtually identical criterion counts. Although both personality disorder groups demonstrated significantly more features of personality disorder than the Depression Only group at six-year follow-up (Figure 1), the difference between Personality Disorder Only and Personality Disorder+Major Depression groups was not statistically significant. This persistence of considerable personality pathology in the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group contradicts the prediction that the presence of the depressive diagnosis would lead to overidentification of personality issues that would not endure. If anything, the personality problems of the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group were slightly more marked than those of the pure PD group at follow-up.

Table 1.

Comparison of symptomatic, functional, and personality stability of in patients with personality disorder, major depression, or both.

| Personality Disorder, no Major Depressive Disorder | Major Depressive Episode, comorbid Personality Disorder | Major Depressive Episode, no Personality Disorder | Significance test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Correlation Between Time Points (r) | Mean | SD | Correlation Between Time Points (r) | Mean | SD | Correlation Between Time Points (r) | F statistic | Df | p | |

| Number of Personality Disorder Symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 29.03a | 15.53 | .50a | 31.39a | 12.77 | .46a | 7.26b | 4.98 | .32b | 103.97 | 2,430 | < .001 |

| Year 6 | 12.77a | 11.95 | 15.45a | 12.97 | 5.56b | 6.68 | 19.54 | 2,430 | < .001 | |||

| GAF Score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 58.68a | 12.57 | .33 | 54.88b | 9.57 | .35 | 60.88a | 10.06 | .39 | 11.28 | 2,430 | < .001 |

| Year 6 | 58.10a | 13.44 | 57.49a | 13.80 | 68.23b | 12.77 | 18.48 | 2,430 | < .001 | |||

| Absolute Value, Change | 11.74 | 9.12 | 10.93 | 8.85 | 11.93 | 8.31 | 0.53 | 2,430 | n.s. | |||

| NEO Neuroticism t-score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 69.92a | 11.90 | .62 | 72.94a | 10.52 | .55 | 61.39b | 12.58 | .55 | 26.77 | 2,391 | < .001 |

| Year 6 | 60.66a | 15.28 | 64.44a | 10.90 | 52.62b | 14.61 | 17.66 | 2,329 | < .001 | |||

| Absolute value, Change | 12.07 | 9.65 | 10.30 | 8.13 | 12.16 | 9.76 | 1.57 | 2,327 | n.s. | |||

| NEO Extroversion t-score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 43.91a | 12.44 | .67 | 37.91b | 12.17 | .67 | 46.78a | 10.58 | .65 | 18.02 | 2,384 | < .001 |

| Year 6 | 44.28a | 11.35 | 40.43b | 12.33 | 47.52a | 10.50 | 17.66 | 2,329 | < .001 | |||

| Absolute value, Change | 7.51 | 6.31 | 7.80 | 6.71 | 6.89 | 5.65 | 0.39 | 2,302 | n.s. | |||

| NEO Openness t-score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 58.47a | 10.82 | .74 | 53.24b | 12.77 | .78 | 55.52a,b | 12.66 | .78 | 6.89 | 2,392 | < .001 |

| Year 6 | 55.71a | 11.28 | 51.42b | 12.49 | 54.96a,b | 11.64 | 4.69 | 2,331 | < .01 | |||

| Absolute value, Change | 6.51 | 4.72 | 6.81 | 5.23 | 6.51 | 4.64 | 0.11 | 2,306 | n.s. | |||

| NEO Agreeableness t-score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 42.56a | 11.79 | .72 | 43.76a | 12.91 | .71 | 48.47b | 10.47 | .63 | 4.89 | 2,378 | < .008 |

| Year 6 | 45.95 | 11.98 | 46.84 | 12.31 | 49.68 | 14.34 | 1.60 | 2,330 | n.s. | |||

| Absolute value, Change | 7.62 | 5.84 | 7.05 | 7.11 | 7.73 | 7.42 | 0.30 | 2,296 | n.s. | |||

| NEO Conscientiousness t-score | ||||||||||||

| Baseline | 38.92 | 14.01 | .69 | 37.01 | 15.17 | .62 | 37.23 | 14.07 | .70 | 0.65 | 2,381 | n.s. |

| Year 6 | 41.79 | 14.93 | 39.74 | 12.23 | 42.67 | 15.58 | 1.29 | 2,327 | n.s. | |||

| Absolute value, Change | 9.29 | 7.71 | 9.77 | 8.27 | 10.35 | 7.23 | 0.28 | 2,291 | n.s. | |||

| PAI Depression t-scores, Year 6 | ||||||||||||

| Cognitive | 57.37a | 15.46 | 63.62b | 16.94 | 55.14a | 17.15 | 8.71 | 2,367 | < .001 | |||

| Affective | 59.12a | 15.92 | 66.53b | 17.35 | 56.32a | 15.96 | 12.27 | 2,367 | < .001 | |||

| Physiological | 57.28a | 11.72 | 62.70b | 12.31 | 54.25a | 12.45 | 14.52 | 2,367 | < .001 | |||

| Total score | 59.46a | 14.81 | 66.96b | 16.03 | 56.26a | 16.21 | 14.81 | 2,367 | < .001 | |||

Means or correlations with differing superscript were significantly different in Bonferroni post-hoc test, p < .05.

Figure 1.

Number of Personality Disorder Criteria met at Baseline and Year 6 in Study Groups.

A further analysis examined the stability of the personality disorder criterion count, to determine whether the presence of a depressive episode resulted in less stable presentations of general personality pathology over time. Moderate stability was observed in the Personality Disorder+Major Depression (r=.51) group and the Personality Disorder Only (r=.46) group, with lower stability in the Depression Only group (r=.32). The limited range of personality disorder criteria observed in the Depression Only group as a function of their selection criteria made lower stability correlations in this group expectable. Of greater interest, there was no significant difference in the stability correlations for personality disordered patients with or without depression.

Table 1 also indicates mean GAF scores at baseline and at year six, mean absolute value of observed GAF changes during this interval, and GAF stability correlations for the three groups. At year six, the Depression Only group demonstrated significantly higher functioning levels than either the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group or the Personality Disorder Only group, while GAF differences at baseline in the Depression Only group were comparable to those of the Personality Disorder Only group. Once again, the persistence of functional impairment in the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group runs counter to the hypothesis that the diagnosis of personality disorder in these depressed patients was an artifact of the baseline depression.

Table 1 also presents mean scores, mean absolute value of observed change, and stability correlations for the three groups on the normal trait domains of the NEO-PI-R. The largest changes were observed on Neuroticism, with mean scores declining over time for all three study groups. Differences between groups were observed at baseline for some traits, as expected from the theoretical and empirical link between five factor traits and personality disorders (27). Of particular interest for the current investigation is the stability of observed differences between groups over time. Across all five trait domains, Personality Disorder+Major Depression and Personality Disorder Only groups either (a) did not differ at baseline and at follow-up, or (b) differed in a consistent manner at both baseline and follow-up. In other words, although the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group and the Personality Disorder group proved to be similar on some traits and different on others, these similarities and differences proved to be persistent over six years. This finding supports the conclusion that the observed personality pattern of the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group at baseline was not apparently the result of a transient mood state.

While the mean scores for groups are informative, group averages can mask instability in personality presentation when some individuals increase on a trait while others decrease on the same trait, resulting in a small average change that obscures large changes at the individual level. Thus, Table 1 also presents the mean absolute value of t-score change on the NEO-PI-R trait domains for each study participant in the three groups. For all five traits, none of the three groups appeared to differ in magnitude of observed personality changes. Finally, examination of six-year trait stability estimates for the five trait domains yielded moderate to large stability estimates for all study groups, ranging from .55 to .78. Tests of the difference between pairs of stability correlations from the different samples across the five traits measured by the NEO-PI-R revealed no differences in stability as a function of group membership over the six year period studied.

To further examine the distinct issues of state vs. trait effects and mood, the status of depressive symptomatology was ascertained at six-year followup. Table 1 illustrates Personality Assessment Inventory-Depression scores for the three groups. For the Depression total score as well as for the Cognitive, Affective, and Physiological subscales, the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group demonstrated higher levels of depressive symptomatology than the Depression Only group at six-year follow-up. In fact, on every depression marker, the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group obtained a score at least one standard deviation above community norms at follow-up, while the Depression Only group mean scores were consistently below this threshold. Along similar lines, follow-up diagnostic evaluation revealed that 29.2% of the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group met criteria for Major Depression at six-year follow-up, whereas only 8.0% of the Depressed Only group still met depression criteria at followup (χ2(1)= 14.44, p < .001). Thus, relative to the Depression Only group, the depressive symptoms of the Personality Disorder+Major Depression group appeared to persist over the six year follow-up interval, which suggests that the depressive symptoms observed in this group at baseline reflected persistent mood problems (consistent with personality disorder), rather than a transient mood state that resulted in an inaccurate diagnosis of personality disorder.

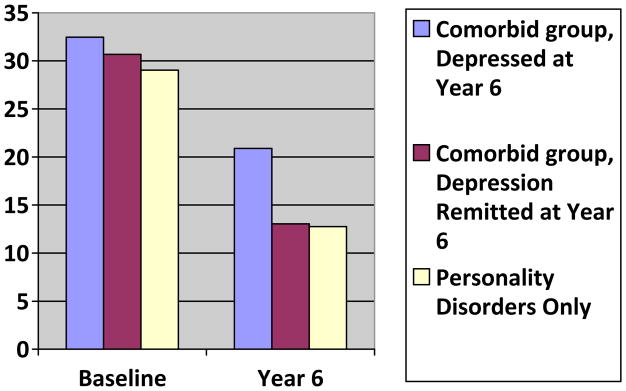

To more closely examine this issue, we compared personality changes in Personality Disorder+Major Depression patients who continued to meet criteria for Major Depression at the 6-year evaluation (n=74) to Personality Disorder+Major Depression patients who no longer met criteria at follow-up (n=167). (Depression Only patients were not included in these analyses because nearly all had remitted.) These comparisons (Table 2) demonstrate that Personality Disorder+Major Depression patients whose depression had remitted by the 6-year follow-up showed comparable stability in personality traits, but greater changes in total personality disorder symptoms and Neuroticism scores. However, comparing these remitted Personality Disorder+Major Depression patients with the Personality Disorder Only group means (Figure 2) reveals no difference between the two groups—in other words, the personality problems in personality disordered patients whose depression had remitted (an average of 13.05 personality disorder criteria met) were directly comparable to the problems observed in personality disordered patients without a baseline depression diagnosis (an average of 12.77 criteria met) at six year followup. Thus, even the Personality Disorder+Major Depression patients whose depression remitted during the study demonstrated personality outcomes that resembled those of typical personality disorder patients.

Table 2.

Personality change in comorbid personality disorder/major depressive patients whose depression did or did not remit over six years.

| PD/MDD at baseline, No MDD at Year 6 | PD/MDD at baseline, MDD at Year 6 | Significance Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Correlation (r), Baseline to Year 6 | Mean | SD | Correlation (r), Baseline to Year 6 | t statistic | Df | p | |

| Number of Personality Disorder Symptoms | |||||||||

| Baseline | 30.67 | 12.96 | .42 | 32.45 | 12.55 | .58 | −1.00 | 245 | n.s. |

| Year 6 | 13.05 | 12.74 | 20.89 | 11.86 | −4.50 | 239 | < .001 | ||

| NEO Trait Domains, Absolute value of Change | |||||||||

| Neuroticism | 11.17 | 8.45 | .56 | 8.12 | 6.85 | .51 | 2.20 | 163 | < .029 |

| Extroversion | 8.00 | 7.03 | .64 | 7.27 | 5.84 | .70 | 0.61 | 159 | n.s. |

| Openness | 6.78 | 5.14 | .76 | 6.89 | 5.47 | .82 | −0.11 | 160 | n.s. |

| Agreeableness | 7.16 | 7.61 | .70 | 6.75 | 5.74 | .73 | 0.34 | 162 | n.s. |

| Conscientiousness | 10.27 | 8.47 | .62 | 8.37 | 7.61 | .60 | 1.27 | 155 | n.s. |

Note: No stability correlations were significantly different in two-tailed Z-tests

Figure 2.

Number of Personality Disorders Criteria met in Personality Disorders+Major Depression patients whose Depression had and had not remitted by Year 6.

Discussion

Because the presence of comorbid personality pathology can complicate the course and treatment of depression (8), clinicians and researchers need to evaluate prominent personality traits and problems for any patient presenting in a depressive episode. However, concerns about the validity of personality assessment in the context of depressed mood (5) have led to suggestions that state-related cognitive distortions or perceptual biases may render it difficult if not impossible to distinguish enduring personality characteristics from more transient phenomena. This study sought to determine whether a comorbid personality disorder diagnosis, assigned in the midst of a major depressive episode, did in fact reflect personality traits or problems that were transient and unstable in nature, or whether the comorbid personality disorder accurately identified long-standing problems and patterns that were likely to persist. Results consistently supported the latter proposition: at six year follow-up, patients initially diagnosed with both major depression and personality disorder resembled other personality disordered patients in their personality pathology and also in their stability and change in normative personality traits. Furthermore, the depressive symptoms initially observed in the Personality Disorder+Major Depression patients appeared to persist more than those of Depression Only patients, at levels well above community norms, supporting the contention that the mood issues identified in these patients were related to trait rather than state phenomena—traits which may adversely affect recovery from depression. Importantly, even when the depressive features did not persist in the Personality Disorder+Major Depression patients, these patients continued to demonstrate levels and stability of personality features comparable to those found in the Personality Disorder Only group. It is important to note that these findings were not a result of any one particular variant of personality disorder, as the four personality disorders studies demonstrated similar stability of the study interval and also had similar rates of comorbid depression.

The relative persistence of personality traits and issues does not mean that they are immutable phenomena. Indeed, as previous studies from our group and others (30–32) have shown, appreciable changes in personality pathology are observable, even over intervals as brief as six months (33, 34). Thus, although previous studies have interpreted personality changes observed during treatment of depression as indicative of state influences on personality assessment, such changes may instead reflect valid alterations of personality characteristics. This interpretation is supported by the current findings that personality problems, while diminishing over time, continue to persist over years in patients with such disorders to a degree well in excess of patients who do not manifest a personality disorder at the index evaluation. Furthermore, the presence of a comorbid major depressive disorder in a patient with personality disorder appears to have little impact on either the persistence of observed personality problems or in the stability of normative personality traits. In either case, the personality problems tend to persist, the normative traits demonstrate moderate to high stability, and depressive features observed in these patients are likely to endure over the long term, rather than ameliorate over time.

In previous reports (35,36) we have suggested that personality problems tend to reflect a hybrid of dynamic and enduring elements that each contribute to an understanding of personality disorder. As noted earlier, an increasing body of evidence suggests that the frequent observation of personality disorders among depressed patients is not an artifact of mood state on personality, but more likely reflects the markedly increased risk for the development of depression among patients with problematic personality traits (10,37). At the same time, studies documenting personality shifts associated with the treatment of depression, rather than calling into question the validity of personality disorder diagnosis, may instead provide intriguing clues to the mechanisms that underlie the more dynamic elements of personality pathology. The interplay between state and trait in the assessment and diagnosis of personality, psychopathology, and their interface is more than one of simply bias or confound. Achieving a greater understanding of this interplay may serve to clarify core processes that lie at the heart of some of the most commonly encountered clinical conditions.

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest are represented by any authors.

References

- 1.Hirschfeld RM, Klerman GL, Clayton PJ, Keller MB, McDonald-Scott P, Larkin BH. Assessing personality: effects of the depressive state on trait measurement. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:695–699. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joffe RT, Regan JJ. Personality and depression. J Psychiatric Research. 1988;22:279–286. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(88)90036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blais MA, Matthews L, Schouten R, O’Keefe SM, Summergrud P. Stability and predictive value of self-report personality traits pre- and post-electroconvulsive therapy: a preliminary study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1991;39:231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fava M, Bouffidcs E, Pava JA, McCarthy K, Stugard RJ, Rosenbaum JF. Personality disorder comorbidity with major depression and response to nuoxetine treatment. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1994;62:160–167. doi: 10.1159/000288918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman M. Diagnosing personality disorders. A review of issues and research methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:225–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030061006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reich J, Noyes R, Jr, Coryell W, O’Gorman TW. The effect of state anxiety on personality measurement. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:760–763. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.6.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Beckham E, Collins JF, Elkin, Sotsky SM, Docherty JP. Personality disorders and treatment outcome in the NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;176:711–718. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reich J. The effect of axis II disorders on the outcome of treatment of anxiety and unipolar depressive disorders: a review. J Pers Disord. 2003;5:387–405. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.5.387.22972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T. Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(1):13–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunderson JG, Morey LC, Stout RL, Skodol AE, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Yen S, Daversa MT, Bender DS. Major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder revisited: longitudinal interactions. J Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1049–1056. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulder RT. Personality pathology and treatment outcome in major depression: a review. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;3:359–371. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kendell RE, DiScipio WJ. Eysenck Personality Inventory scores of patients with depressive illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114:767–770. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.511.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loranger AW, Lenzenweger MF, Gartner AF, Susman VL, Herzig J, Zammit GK, Gartner JD, Abrams RC, Young RC. Trait-state artifacts and the diagnosis of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:720–727. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320044007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griens AM, Jonker K, Spinhoven P, Blom MB. The influence of depressive state features on trait measurement. J Affect Disord. 2002;1:95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fava M, Farabaugh AH, Sickinger AH, Wright E, Alpert JE, Sonawalla S. Personality disorders and depression. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1049–1057. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagby RM, Rector NA, Bindseil K, Dickens SE, Levitan RD, Kennedy SH. Self-report ratings and informants’ratings of personalities of depressed outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:437–438. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Skodol AE, McGlashan TH, Morey LC, Stout RL, Zanarini MC, Grilo CM, Oldham JM, Keller MB. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: development, aims, design, and sample characteristics. J Personal Disord. 2000;14:300–315. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:256–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Kellman SE, Hyler SE, Doidge N, Rosnick L, Gallaher PE. Comorbidity of Axis I and Axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:571–578. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, Dyck IR, McGlashan TH, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Oldham JM, Gunderson JG. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:295–302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition. New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Yong L. The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) Belmont, MA: McLean Hospital; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanislow CA, Little TD, Ansell EB, Grilo CM, Daversa M, Markowitz JC, Pinto A, Shea MT, Yen S, Skodol AE, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH. Ten-year stability and latent structure of the DSM-IV schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Abnormal Psychol. 2009;118:507–519. doi: 10.1037/a0016478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychol Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Morey LC, Grilo CM, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: reliability of Axis I and II diagnoses. J Personal Disord. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO-PI profesional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa PT, Widiger TA. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman MB, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, et al. The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morey LC. Professional manual for the Personality Assessment Inventory. 2. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grilo CM, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Stout RL, Pagano ME, Yen S, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, McGlashan T. Two-year stability and change in Schizotypal, Borderline, Avoidant, and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorders. J Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:767–775. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. The Longitudinal Course of Borderline Psychopathology: 6-Year Prospective Follow-Up of the Phenomenology of Borderline Personality Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:274– 283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lenzenweger MF, Johnson MD, Willett JB. Individual growth curve analysis illuminates stability and change in personality disorder features: the longitudinal study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1015–1024. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunderson JG, Bender DS, Sanislow C, Yen S, Rettew JB, Dolan-Sewell R, Dyck I, Morey LC, McGlashan TH, Shea MT, Skodol AE. Plausibility and possible determinants of sudden “remissions” in borderline patients. Psychiatry. 2003;66:111–119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.66.2.111.20614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shea MT, Stout RL, Gunderson JG, Morey LC, Grilo CM, McGlashan T, Skodol AE, Dolan-Sewell R, Dyck I, Zanarini MC, Keller MB. Short-term diagnostic stability of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2036–2041. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Ravelski E, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Bender D, Stout RL, Yen S, Pagano M. Two-year prevalence and stability of individual DSM-IV criteria for Schizotypal, Borderline, Avoidant, and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:883–889. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Shea MT, Yen S, Stout RL, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH. Comparison of diagnostic models for personality disorders. Psychol Med. 2007;37:983–994. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. Personality and major depression: A Swedish longitudinal, population-based twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1113–1120. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]