Abstract

Background

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is an alternative to post-operative whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) following resection of brain metastases. At our institution, CyberKnife (CK) is considered for local treatment of large cavities ≥2 cm. In this study, we aimed to evaluate patterns of failure and characterize patients best suited to treatment with this approach.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 30 patients treated with CK to 33 resection cavities ≥2 cm between 2011 and 2014. Patterns of intracranial failure were analyzed in 26 patients with post-treatment imaging. Survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and prognostic factors examined with log-rank test and Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

The most frequent histologies were lung (43 %) and breast (20 %). Median treatment volume was 25.1 cm3 (range 4.7–90.9 cm3) and median maximal postoperative cavity diameter was 3.8 cm (range 2.8–6.7). The most common treatment was 30 Gy in 5 fractions prescribed to the 75 % isodose line. Median follow up for the entire cohort was 9.5 months (range 1.0–34.3). Local failure developed in 7 treated cavities (24 %). Neither cavity volume nor CK treatment volume was associated with local failure. Distant brain failure occurred in 20 cases (62 %) at a median of 4.2 months. There were increased rates of distant failure in patients who initially presented with synchronous metastases (p = 0.02). Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis (LMC) developed in 9 cases, (34 %). Salvage WBRT was performed in 5 cases (17 %) at a median of 5.2 months from CK. Median overall survival was 10.1 months from treatment.

Conclusions

This study suggests that adjuvant CK is a reasonable strategy to achieve local control in large resection cavities. Patients with synchronous metastases at the time of CK may be at higher risk for distant brain failure. The majority of cases were spared or delayed WBRT with the use of local CK therapy.

Keywords: Brain metastases, Radiosurgery, CyberKnife

Background

Approximately 20–40 % of patients with cancer will develop intracranial metastases [1]. Treatment options for these patients include surgery, whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). For patients with large intracranial metastases, local control with single modality treatment is poor. Studies have shown <10 % complete response rate with WBRT for tumors approximately 2 cm in diameter [2]. Local control is maintained in less than 50 % of tumors larger than 2 cm after radiosurgery alone [3]. Randomized studies have demonstrated that WBRT following surgical resection of a solitary metastasis decreases the rate of local recurrence within the surgical bed as well as distant recurrence within the brain [4]. However, WBRT is associated with decreased cognitive function and quality of life without a proven overall survival benefit [5, 6]. SRS to the surgical bed is an emerging alternative that may allow WBRT to be deferred for a select group of patients.

Large resection cavities are less amenable to single fraction SRS given the high risk of radiation damage with increasing cavity size [7]. Fractionated SRS following surgical resection has been shown to be feasible and safe utilizing linear accelerator-based and CyberKnife (CK) technologies for cavities greater than 3 cm [8–10]. However, there is limited information on optimal patient selection for this treatment approach. In particular, questions remain regarding risk of local and distant failure, especially leptomeningeal carcinomatosis (LMC). In this study, we report outcomes following single or multi-fraction SRS for large brain metastases after surgical resection. We quantify local control and assess patient and treatment characteristics associated with intracranial failure.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients were considered for SRS following surgical resection. Patients recommended for SRS had low intracranial metastatic burden (1–4 metastases) and good overall prognosis as judged by performance status, status of extracranial disease, age, and histology [11]. CK was considered for lesions ≥ 2 cm, lesions with gross residual or recurrent disease, and lesions near critical structures. SRS was ideally performed after full post-operative wound healing 4–6 weeks from the time of resection.

With the approval of the institutional review board, we retrospectively analyzed medical records of all patients treated with single or multiple fraction CyberKnife (CK) SRS to surgical beds of intracranial metastases ≥2 cm at the time of radiosurgery. Cases were performed between 2011 and 2014 at the Pennsylvania Hospital (University of Pennsylvania Health System). Patients with a history of WBRT prior to CK or with a plan for CK followed by WBRT were excluded from this study. Patients with synchronous unresected lesions treated with SRS alone were included in this study.

Data collection

All clinical data was obtained from electronic medical records and Social Security Death Index. The status of extracranial disease was defined as none, stable, or progressive based on systemic imaging prior to CK. Those who were diagnosed at the time of intracranial disease or who had no treatment to their primary site were characterized as newly diagnosed. Post-operative MRI was obtained 24–48 h after resection in each case. Gross total resection (GTR) was defined as no residual enhancing tumor after surgery on MRI. Graded prognostic assessment (GPA) class was assigned to each patient according to methods described by Sperduto et al. [11].

Radiosurgical technique and follow up

The CyberKnife (Accuray, Sunnyvale, CA) was used to deliver all radiosurgical treatments. Brain MRI was obtained at 1-mm slices with gadolinium contrast. The MRI scan was fused to the computed tomography scan (CT) for target delineation. The gross tumor volume (GTV) was contoured as the edge of the resection cavity including contrast enhancement. The clinical tumor volume (CTV) was an expansion of 2–3 mm margin added to the GTV. Planning target volume (PTV) was the same as the CTV.

Dose was based on the size of the PTV and preference of the treating physician. Larger cavities were typically treated to 30 Gy in five fractions and smaller cavities to 24 Gy in three fractions as has been previously described [12]. With a plan maximal dose of 100 %, doses were prescribed to the 55–90 % isodose lines. The PTV was covered by at least 95 % of the dose in all cases. Conformality index was typically between 1.1 and 1.2, and smaller than 1.3. The number of beams was between 100 and 200 and treatment times were kept under 1 h.

After CK, follow-up included clinical visits at 1 month and then 3-month intervals. Surveillance MRI was obtained 2–3 months following CK and subsequently every 3 months. Local failure was defined as new and progressive nodular enhancement in the resection bed over a minimum follow-up of 4 months, or two consecutive MRI scans. Radionecrosis was evaluated using dynamic contrast-enhanced perfusion imaging (DCE-MRI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). Radionecrosis rather than local progression was suggested by 1) low cerebral blood volume 2) increased lactate/creatine ratio and decreased choline/creatine ratio and 3) regression or stability over a minimum follow-up of 4 months without additional treatment [13, 14]. Clinical decisions regarding local progression versus radionecrosis were made in a multidisciplinary setting including input from a diagnostic radiologist. Distant failure was defined as new brain metastases away from the surgical cavity or development of LMC, diagnosed based on MRI, clinical symptoms, and/ or cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp). Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with all cases included in the analysis. Living patients or those lost to follow-up were censored at the date of last clinical encounter. Local and distant failure was examined by the Kaplan-Meier method in cases where post-CK imaging was available. Patients who received salvage WBRT were censored at last MRI prior to WBRT for the failure analysis. Univariable analyses were computed using log-rank test and a p value ≤ 0.1 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable analysis was performed via the Cox proportional hazards ratio and p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For this exploratory, hypothesis-generating study we made no adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results and discussion

A total of 30 patients were treated with CK to 33 resection cavities. Fifteen patients (50 %) were male and 15 (50 %) were female. The most frequent histologies were lung (43 %) and breast (20 %). Median GPA was 2.5 (range 1–4). Gross total resection (GTR) was achieved in 19 (58 %) cases. A median of one synchronous metastasis was observed in 10 patients (range 1–3) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Sexa | |

| Male (%) | 15 (50) |

| Female (%) | 15 (50) |

| Age in years at CK | |

| Median (range) | 58 (28–97) |

| Primary tumora | |

| NSCLC (%) | 12 (40) |

| SCLC (%) | 1 (3) |

| Breast (%) | 6 (20) |

| Melanoma (%) | 4 (13) |

| Other (%) | 7 (23) |

| Extracranial diseasea | |

| Newly diagnosed/ progressing (%) | 15 (50) |

| None/ stable (%) | 15 (50) |

| Median GPA classa | |

| Breast | 2 (1.5–3.5) |

| NSCLC/SCLC | 2.5 (1.5–3.5) |

| Melanoma | 3 (2–3) |

| GI | 2 (2–4) |

| Other | 2.75 (1–3.5) |

| Postoperative diameter in cm | |

| Median (range) | 3.8 (2.8–6.7) |

| Surgery extentb | |

| GTR (%) | 19 (58) |

| STR (%) | 14 (42) |

| Synchronous intact metsa | |

| Yes (%) | 10 (33) |

| No (%) | 20 (67) |

| Weeks from resection to CK | |

| Median (range) | 7 (4–19) |

Preop preoperative, CK Cyberknife, GTR gross total resection, STR subtotal resection, mets metastases, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer, SCLC small cell lung cancer, GI gastrointestinal

a N = 30 patients

b N = 33 cases

SRS was performed a median of 7 weeks from resection (range 4–19 weeks). Causes of delay included wound infection (n = 1), pulmonary embolism (n = 1), treatment of primary site (n = 1), systemic staging (n = 2), insurance referral delay (n = 2), and intracranial re-staging (n = 7). At the time of treatment planning, interval growth was observed in 13 cavities.

The median SRS dose to the resection cavity was 30 Gy (range 16–35) delivered in 1 to 5 fractions (median, 5 fractions). Median cavity volume was 17.5 cm3 (range 2.4–69.8 cm3) and median treatment volume was 25.1 cm3 (range 4.7–90.9 cm3). Median maximal postoperative cavity diameter was 3.8 cm (range 2.8–6.7) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Fractionation schemes

| No. of fractions | N | Median dose (Gy) | Median dose per fraction (Gy) | Median diameter (cm) | Median isodose line (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 18.5 (16–21) | 18.5 (16–21) | 2.8 (2.8–2.9) | 61 (55–66) |

| 3 | 5 | 24 (24) | 8 (8) | 3.6 (3.1–4.5) | 76 (71–79) |

| 5 | 26 | 30 (25–35) | 6 (5–7) | 4.2 (3.2–6.7) | 76 (64–88) |

No. number, PTV planning treatment volume

The median clinical follow up for the entire cohort of 30 cases was 9.5 months (range 1.0–34.3), and for the 13 living patients was 16.9 months (range 4.4–35.2). Twenty-six patients with 29 treated cavities were followed with serial imaging.

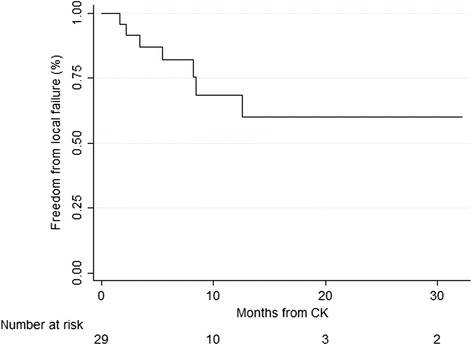

Local failure occurred in 7 cavities, for a crude rate of 24 %. Median time to local failure was 3.4 months in the cases that failed. Six-month and one-year actuarial local control were 82.3 and 68.5 % [Fig. 1]. Six of the 7 cases with local failure had images available for evaluation. Failure occurred within the GTV in 5 instances and 3 mm from the GTV in 1 case. Evaluation of preoperative tumor diameter, postoperative tumor diameter, GTV, and PTV at a variety of cut-off points showed no association with local failure (p > 0.2).

Fig. 1.

Freedom from local intracranial progression after CK

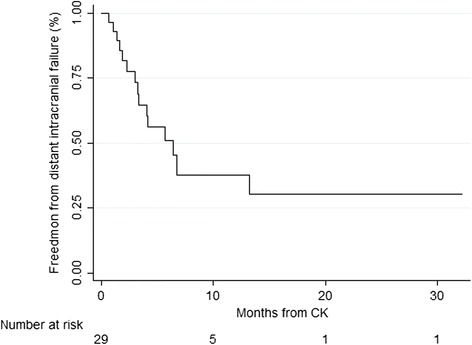

Of the 26 patients with available follow-up imaging, distant brain failure occurred in 16 (62 %) at a median of 4.2 months from CK. Actuarial 6-month and 1-year distant brain failure were 55.3 and 73.9 % [Fig. 2]. On univariable analysis, presence of synchronous metastases at the time of diagnosis (p = 0.04), dose per fraction <6 Gy (p = 0.07), and total dose <30 Gy (p = 0.1) were associated with distant failure. On multivariable analysis, synchronous metastases at diagnosis was significantly associated with distant failure (p = 0.02, 95 % CI 1.33–14.5).

Fig. 2.

Freedom from distant intracranial progression after CK

Among the 26 cases with follow-up imaging, 9 developed leptominengeal disease, for a crude rate of 34 %. On univariable analysis, simultaneous resection of multiple metastases (p = 0.01) and >50 days delay to CK (p = 0.03) were associated with LMC. There was no association with tumor histology, cavity diameter, cavity volume, or cavity location (p > 0.3). On multivariable analysis, no variable was significantly associated with LMC.

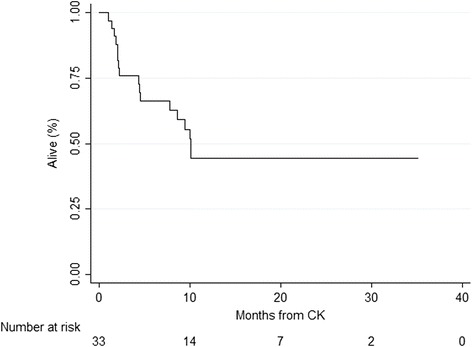

By Kaplan-Meier analysis, the median overall survival was 10.1 months from CK [Fig. 3]. On univariable analysis, male gender (p = 0.01), the presence of synchronous metastases (p = 0.07), GPA ≤ 3 (p = 0.04) and age >60 years (p = 0.1) were statistically significantly associated with overall survival. On multivariable analysis, male gender remained statistically significant (p = 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Survival after CK

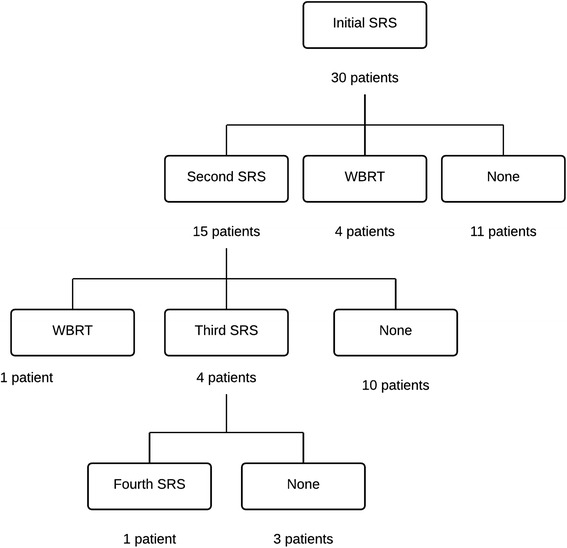

Two patients underwent upfront resection of two simultaneous lesions. Eight were treated with concurrent SRS for synchronous, unresected metastases found at the time of CK. Seven patients underwent additional SRS [Fig. 4]. Five of 30 total patients (17 %) were treated with salvage WBRT at a median of 5.2 months from CK. Patients with leptomeningeal disease were significantly more likely to receive salvage WBRT (p = 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Outcomes after Initial SRS

Three patients developed clinically significant radionecrosis requiring treatment with steroids (10 %). None had neurosurgical resection. Two patients had new onset seizures within 3 months of CK.

Discussion

For patients treated with surgical resection of intracranial metastases, whole brain radiation therapy has been shown to improve intracranial control without an overall survival benefit [5, 7]. Neurocognitive decline and decreased quality of life have been associated with whole brain radiation and led to increasing use of local therapies to delay or defer WBRT after resection [6].

Numerous studies have reported outcomes of single fraction stereotactic radiosurgery to small resection cavities in patients without prior WBRT [Table 3]. One year actuarial local control rates range from 78 to 100 % and distant failures occur in 33–66 % of patients [15, 16, 17, 18]. Whole brain radiation is reported as salvage therapy in approximately one third of patients.

Table 3.

Literature of single fraction SRS to the resection cavity

| Authors & year | No. cavities | Treatment modality | Median dose (Gy) | Crude LF (%) | DF (%) | Salvage WBRT (%) | LMC (%) | MS (mos) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwai et al., 2008 [19] | 21 | GK | 17 | 24 | 48 | NR | 24 | 20 |

| Do et al., 2009 [26] | 33 | LINAC | 15 | 12 | 63 | 47 | NR | 12 |

| Jagannathan et al., 2009 [27] | 47 | GK | 19 | 7 | 87 | 28 | NR | 11 |

| Karlovits et al., 2009 [28] | 52 | LINAC | 15 | 8 | 55 | 31 | NR | 15 |

| Limbrick et al., 2009 [29] | 16 | GK | 20 | 27 | 60 | 40 | NR | 20 |

| Hwang et al., 2010 [30] | 25 | GK | 15–20a | 0 | 33 | NR | NR | 15 |

| Kalani et al., 2010 [31] | 68 | GK | 15 | 21 | NR | NR | NR | 13.2 |

| Jensen et al., 2011 [15] | 112 | GK | 17 | 13 | 54 | 37 | 7.5 | 10.9 |

| Rwigema et al., 2011 [20] | 77 | CK | 18 | 26 | 47 | 26 | NR | 14.5 |

| Kelly et al., 2012 [32] | 18 | LINAC | 18 | 11 | 35 | 24 | NR | N/A |

| Ogiwara et al., 2012 [33] | 56 | GK | 16 | 9 | 38 | 14 | NR | 21 |

| Prabhu et al., 2012 [22]b | 64 | LINAC | 18 | 17 | NR | NR | NR | 13 |

| Robbins et al., 2012 [16] | 85 | LINAC | 16 | 19 | 55 | 35 | 8.2 | 12 |

| Broemme et al., 2013 [23]b | 44 | LINAC | 17c, 24d | 9 | 66 | 36 | NR | 15.9 |

| Hartford et al., 2013 [35] | 49 | LINAC | 10 | 16 | 63 | 45 | NR | NR |

| Luther et al., 2013 [17] | 120 | GK | 16 | 14 | 40 | NR | NR | NR |

| Brennan et al., 2014 [34] | 40 | LINAC | 18 | 30 | 47 | NR | NR | 14.7 |

| Ojerholm et al., 2014 [18] | 96 | GK | 16 | 18 | 54 | 33 | 14 | 22.3 |

No. number, GK Gamma Knife, LINAC linear accelerator, CK Cyberknife, LF local failure, DF distant failure, MS median survival, LMC leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, mos months, NR not reported, N/A not applicable

aReported range

bMajority single fraction SRS

cMedian single fraction dose

dMedian multi fraction dose

Large lesions are less amenable to single fraction treatment given increasing dose to surrounding normal tissue and risk of radiation necrosis, especially for lesions >3 cm [5]. Previous studies have established safety and efficacy of fractionated SRS in treatment of large brain metastases, with rates of radionecrosis from 2 to 6 % [8–10]. However, there are few reports describing outcomes for patients with large resection cavities treated with fractionated SRS without WBRT [Table 4]. Reported cases are characterized by cavity volumes ranging from 8.7 to 29.5 cm3 and low rates of radionecrosis, from 3 to 9 % [19–23]. Series of patients treated with predominantly fractionated regimens report 71–91 % local control, comparable to single fraction series. Similarly, approximately one third of patients are salvaged with whole brain radiation.

Table 4.

Literature of single or multiple fraction SRS to resection cavity

| Authors & year | No. cavities | Treatment modality | Median dose (Gy) | Crude LF (%) | DF (%) | Salvage WBRT (%) | LMC (%) | MS (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi et al., 2012 [21]a | 102 | CK | 16b | 11 | 53 | 28 | NR | 15.6 |

| Minniti et al., 2013 [24] | 101 | LINAC | 27 | 8 | 53 | 27 | NR | 17 |

| Ling et al., 2015 [25] | 100 | CK | 22 | NR | 64.1 | 33 | 6 | 12.7 |

| Present study | 33 | CK | 30 | 24 | 62 | 17 | 34 | 10.1 |

No. number, CK Cyberknife, LINAC linear accelerator, LF local failure, DF distant failure, MS median survival, LMC leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, mos months, NR not reported

aMajority multi fraction SRS

bBiologically equivalent single fraction dose

In some series, increased risk of local failure is seen with increasing preoperative diameter or cavity size [Table 5]. Brennan et al. report 39.1 % local failure in patients with tumors ≥3 cm as compared to 7.5 % with maximal diameter <3 cm [24]. Prabhu et al. report a hazard ratio of 1.04 for local recurrence with increasing PTV volume [25]. In these series, patients were predominantly treated with single fraction SRS. Our series consisted of patients with large lesions treated most often with fractionated SRS. Increased risk of local failure was not seen in association with increasing tumor diameter, increasing cavity size, or larger treatment volumes.

Table 5.

Significantly associated clinical characteristics

| Authors | LF | DF | LMC | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwai et al. [19] | Dose < 18Gy | N/A | Infratentorial location | N/A |

| Jagannathan et al. [27] | Greater treated volume | N/A | N/A | Systemic progression |

| Karlovits et al. [31] | N/A | N/A | N/A | >1 intracranial metastasis |

| Extracranial disease | ||||

| Jensen et al. [15] | Preop diameter > 3 cm | Dose <35Gy | N/A | N/A |

| Rwigema et al. [20] | Greater PTV | N/A | N/A | Age |

| RPA score | ||||

| Choi et al. [21] | N/A | Melanoma histology | N/A | KPS Preop diameter |

| Ogiwara et al. [33] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Extracranial metastases |

| Prabhu et al. [22] | Larger PTV volume | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Marginal dose <18 Gy | ||||

| Brennan et al. [34] | NSCLC histology | Infratentorial location | N/A | N/A |

| Preop diameter > 3 cm | ||||

| Dural/ pial involvement | ||||

| Hartford et al. [35] | Preop diameter ≥ 2 cm | Preop diameter ≥ 2 cm | N/A | GPA ≤1 |

| Ojerholm et al. [18] | Preop diameter ≥ 3 cm | N/A | Breast histology | New diagnosis or untreated primary |

| Infratentorial location | ||||

| Ling et al. [25] | N/A | Uncontrolled systemic disease | N/A | Increasing no. metastases |

| Melanoma histology | Uncontrolled systemic disease | |||

| Increasing no. brain metastases | ||||

| Present study | N/A | Synchronous metastases | N/A | Male gender |

LF local failure, N/A not applicable, PTV planning treatment volume, Preop preoperative, LMC leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, CK Cyberknife, OS overall survival, RPA recursive partitioning analysis, KPS Karnofsky performance status, GPA graded prognostic assessment, no. number

Distant failures in reported series of fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery range from 53 to 64 % [26, 27, 28]. In our series, distant failure occurred in 62 % of treated patients. Our study did not show any correlation between cavity size and increased distant failure, although we did observe increased rates of distant failure with synchronous metastases at the time of resection. Other studies have shown a similar trend towards increased distant failure when multiple metastases are present at the time of initial SRS [29, 30]. As in other series, the majority of patients were salvaged with additional SRS and spared WBRT.

Rates of distant failure from leptomeningeal carcinomatosis have been less frequently reported. Given the lack of data for this entity, our study adds to the literature in regards to rates after local therapy. For patients treated with single fractions, rates range from 4.5 to 24 % [31, 32, 33, 34]. A single report of patients treated predominantly with multi-fraction SRS demonstrated a rate of 6 % [35]. Our rate of 34 % is higher than that reported for surgical cavities treated with CK and GK. This risk has been associated previously with breast histology and infratentorial location [18, 19]. In this cohort, histology, location, and cavity size had no association with risk of LMC. Clinical factors associated with LMC remain to be characterized.

In our series, we observed an association between male gender and overall survival which was independent of age, RPA classification, presence of synchronous metastases, and tumor histology. This association has not been previously observed in series of SRS to resection cavities. However, male gender has been reported as an independent prognostic factor in analyses by Serizawa et al. for patients treated with GK to multiple simultaneous brain metastases [36, 37].

This study is limited by small patient numbers and its retrospective nature. Patient selection was biased towards those with higher performance status and lower metastatic burden as compared to those who may have been offered WBRT alone. Long-term neurocognitive function and death due to neurologic progression were not available for comparison to regimens using WBRT. Doses delivered were done at the discretion of the treating physician, although the study is strengthened by institutionally based planning constraints and follow-up.

Reports of single and multi-fraction SRS using CK remain largely from retrospective single institution series. Ongoing studies comparing postoperative SRS to observation (MD Anderson Cancer Center 2009–0381) and WBRT (Intergroup N107C) will further clarify the role of SRS after resection of a single metastasis. Neoadjuvant SRS is an alternate treatment algorithm for local control in large brain metastases. Phase I/II studies are evaluating the role of neoadjuvant therapy for resectable lesions (NCT01891318) and future studies may incorporate SRS into treatments for brain metastases which are unresectable at presentation. Findings from these studies will continue to clarify which patients are most suitable candidates for local therapy following resection of a brain metastasis and to evaluate alternate treatment paradigms in this setting.

Conclusions

Adjuvant SRS to the resection cavity for patients with large brain metastases provides local control while sparing patients potential long-term neurocognitive risk of WBRT. Local and distant control can be achieved independent of tumor diameter and cavity volume. Patients with synchronous metastases may have higher rates of distant failure when treated with local therapies alone.

Abbreviations

- WBRT

Whole brain radiation therapy

- SRS

Stereotactic radiosurgery

- LMC

Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis

- CK

CyberKnife

- RPA

Recursive partitioning analysis

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- GTR

Gross total resection

- CT

Computed tomography

- GTV

Gross tumor volume

- CTV

Clinical target volume

- PTV

Planning target volume

- Preop

Preoperative

- STR

Subtotal resection

- mets

Metastases

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- SCLC

Small cell lung cancer

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- No.

Number

- LF

Local failure

- DF

Distant failure

- MS

Median survival

- mos

Months

- NR

Not reported

- N/A

Not applicable

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JV contributed to data collection, statistical analysis, and writing of the manuscript. EO contributed to statistical analysis and manuscript editing. AH contributed to data collection. CB compiled the initial patient dataset. RM aided in treatment planning. MB aided in treatment planning. JK contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning, and contributed to manuscript editing. SN contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning, and contributed to manuscript editing. GG contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning, and contributed to manuscript editing. RL contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning and follow up, and contributed to manuscript editing. DO contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning and follow up, and contributed to manuscript editing. SB contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning and follow-up, and contributed to manuscript editing. JL contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning, and contributed to manuscript editing. MAB conceptualized the initial study plan, contributed patients to the study, aided in radiation treatment planning and follow-up, and aided in data collection, analysis, and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Vogel, Email: jennifer.vogel@uphs.upenn.edu.

Eric Ojerholm, Email: Eric.Ojerholm@uphs.upenn.edu.

Andrew Hollander, Email: Andrew.Hollander@uphs.upenn.edu.

Cynthia Briola, Email: Cynthia.Briola@uphs.upenn.edu.

Rob Mooij, Email: Rob.Mooij@uphs.upenn.edu.

Michael Bieda, Email: Michael.Bieda@uphs.upenn.edu.

James Kolker, Email: James.Kolker@uphs.upenn.edu.

Suneel Nagda, Email: Suneel.Nagda@uphs.upenn.edu.

Geoffrey Geiger, Email: Geoffrey.Geiger@uphs.upenn.edu.

Jay Dorsey, Email: Jay.Dorsey2@uphs.upenn.edu.

Robert Lustig, Email: Robert.Lustig@uphs.upenn.edu.

Donald M. O’Rourke, Email: Donald.Orourke@uphs.upenn.edu

Steven Brem, Email: Steven.Brem@uphs.upenn.edu.

John Lee, Email: John.Lee3@uphs.upenn.edu.

Michelle Alonso-Basanta, Email: Michelle.Alonso-Basanta@uphs.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.Nussbaum ES, Djalilian HR, Cho KH, Hall WA. Brain metastases. Histology, multiplicity, surgery, and survival. Cancer. 1996;78:1781–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961015)78:8<1781::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieder C, Berberich W, Schnabel K. Tumor-related prognostic factors for remission of brain metastases after radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(97)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelbaum MA, Angelov L, Lee SY, Li L, Barnett GH, Suh JH. Local control of brain metastases by stereotactic radiosurgery in relation to dose to the tumor margin. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:907–12. doi: 10.3171/jns.2006.104.6.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw E, Scott C, Souhami L, Dinapoli R, Kline R, Loeffler J, et al. Single dose radiosurgical treatment of recurrent previously irradiated primary brain tumors and brain metastases: final report of RTOG protocol 90–05. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:291–8. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Dempsey RJ, Mohiuddin M, Kryscio RJ, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1485–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR, Allen PK, Lang FF, Kornguth DG, et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:1037–44. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kocher M, Soffietti R, Abacioglu U, Villa S, Fauchon F, Baumert BG, et al. Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: results of the EORTC 22952–26001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:134–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst-Stecken A, Ganslandt O, Lambrecht U, Sauer R, Grabenbauer G. Phase II trial of hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for brain metastases: results and toxicity. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fahrig A, Ganslandt O, Lambrecht U, Grabenbauer G, Kleinert G, Sauer R, et al. Hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for brain metastases--results from three different dose concepts. Strahlenther Onkol. 2007;183:625–30. doi: 10.1007/s00066-007-1714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fokas E, Henzel M, Surber G, Kleinert G, Hamm K, Engenhart-Cabillic R. Stereotactic radiosurgery and fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy: comparison of efficacy and toxicity in 260 patients with brain metastases. J Neurooncol. 2012;109:91–8. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0868-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sperduto P, Chao S, Sneed P, Luo X, Suh J, Roberge D, et al. Diagnosis-specific prognostic factors, indexes, and treatment outcomes for patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases: a multi-institutional analysis of 4,259 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue HK, Sato H, Suzuki Y, Saitoh J, Noda S, Seto K, et al. Optimal hypofractionated conformal radiotherapy for large brain metastases in patients with high risk factors: a single-institutional prospective study. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:231–5. doi: 10.1186/s13014-014-0231-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen VA, Simonsen HJ, Law I, Larsson HB, Hansen AE. Evaluation of dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted perfusion MRI in the differentiation of tumor recurrence from radiation necrosis. Neuroradiology. 2013;55:361–9. doi: 10.1007/s00234-012-1127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamada K, Houkin K, Abe H, Sawamura Y, Kashiwaba T. Differentiation of cerebral radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurol Med Chir. 1997;37:250–6. doi: 10.2176/nmc.37.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen CA, Chan MD, McCoy TP, Bourland JD, de Guzman AF, Ellis TL, et al. Cavity-directed radiosurgery as adjuvant therapy after resection of a brain metastasis. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1585–91. doi: 10.3171/2010.11.JNS10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robbins JR, Ryu S, Kalkanis S, Cogan C, Rock J, Movsas B, et al. Radiosurgery to the surgical cavity as adjuvant therapy for resected brain metastasis. Neurosurgery. 2012;71:937–43. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31826909f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luther N, Kondziolka D, Kano H, Mousavi SH, Engh JA, Niranjan A, et al. Predicting tumor control after resection bed radiosurgery of brain metastases. Neurosurgery. 2013;73:1001,6. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ojerholm E, Lee JY, Thawani JP, Miller D, O’Rourke DM, Dorsey JF, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery to the resection bed for intracranial metastases and risk of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(Suppl 2):75–83. doi: 10.3171/2014.6.GKS14708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwai Y, Yamanaka K, Yasui T. Boost radiosurgery for treatment of brain metastases after surgical resections. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:181,6. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rwigema JC, Wegner RE, Mintz AH, Paravati AJ, Burton SA, Ozhasoglu C, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery to the resection cavity of brain metastases: a retrospective analysis and literature review. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2011;89:329–37. doi: 10.1159/000330387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi CY, Chang SD, Gibbs IC, Adler JR, Harsh GR, 4th, Atalar B, et al. What is the optimal treatment of large brain metastases? An argument for a multidisciplinary approach. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:688–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prabhu R, Shu HK, Hadjipanayis C, Dhabaan A, Hall W, Raore B, et al. Current dosing paradigm for stereotactic radiosurgery alone after surgical resection of brain metastases needs to be optimized for improved local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broemme J, Abu-Isa J, Kottke R, Beck J, Wiest R, Malthaner M, et al. Adjuvant therapy after resection of brain metastases. Frameless image-guided LINAC-based radiosurgery and stereotactic hypofractionated radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189:765–70. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0409-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minniti G, Esposito V, Clarke E, Scaringi C, Lanzetta G, Salvati M, et al. Multidose stereotactic radiosurgery (9 Gy × 3) of the postoperative resection cavity for treatment of large brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:623–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ling DC, Vargo JA, Wegner RE, Flickinger JC, Burton SA, Engh J, et al. Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery to the resection cavity for large brain metastases: clinical outcomes, predictors of intracranial failure, and implications for optimal patient selection. Neurosurgery. 2015;76:150,6. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Do L, Pezner R, Radany E, Liu A, Staud C, Badie B. Resection followed by stereotactic radiosurgery to resection cavity for intracranial metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:486–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagannathan J, Yen CP, Ray DK, Schlesinger D, Oskouian RJ, Pouratian N, et al. Gamma Knife radiosurgery to the surgical cavity following resection of brain metastases. J Neurosurg. 2009;111:431–8. doi: 10.3171/2008.11.JNS08818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlovits BJ, Quigley MR, Karlovits SM, Miller L, Johnson M, Gayou O, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery boost to the resection bed for oligometastatic brain disease: challenging the tradition of adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27:E7. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.FOCUS09191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Limbrick DD, Jr, Lusis EA, Chicoine MR, Rich KM, Dacey RG, Dowling JL, et al. Combined surgical resection and stereotactic radiosurgery for treatment of cerebral metastases. Surg Neurol. 2009;71:280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang SW, Abozed MM, Hale A, Eisenberg RL, Dvorak T, Yao K, et al. Adjuvant Gamma Knife radiosurgery following surgical resection of brain metastases: a 9-year retrospective cohort study. J Neurooncol. 2010;98:77–82. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalani MY, Filippidis AS, Kalani MA, Sanai N, Brachman D, McBride HL, et al. Gamma Knife surgery combined with resection for treatment of a single brain metastasis: preliminary results. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(Suppl):90–6. doi: 10.3171/2010.8.GKS101067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly PJ, Lin YB, Yu AY, Alexander BM, Hacker F, Marcus KJ, et al. Stereotactic irradiation of the postoperative resection cavity for brain metastasis: a frameless linear accelerator-based case series and review of the technique. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogiwara H, Kalakota K, Rakhra SS, Helenowski IB, Marymont MH, Kalapurakal JA, et al. Intracranial relapse rates and patterns, and survival trends following post-resection cavity radiosurgery for patients with single intracranial metastases. J Neurooncol. 2012;108:141–6. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennan C, Yang TJ, Hilden P, Zhang Z, Chan K, Yamada Y, et al. A phase 2 trial of stereotactic radiosurgery boost after surgical resection for brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartford AC, Paravati AJ, Spire WJ, Li Z, Jarvis LA, Fadul CE, et al. Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery without whole-brain radiation therapy for brain metastases: potential role of preoperative tumor size. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:650–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serizawa T, Higuchi Y, Ono J, Matsuda S, Nagano O, Iwadate Y, et al. Gamma knife surgery for metastatic brain tumors without prophylactic whole-brain radiotherapy: results in 1000 consecutive cases. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(suppl):S86–90. doi: 10.3171/sup.2006.105.7.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serizawa T, Hiari O, Nagano O, Higuchi Y, Matsuda S, Ono J, et al. Gamma knife surgery for 1–10 brain metastases without prophylactic whole-brain radiation therapy: analysis of cases meeting the Japanese prospective multi-institute study (JLGK0901) inclusion criteria. J Neurooncol. 2010;90:163–7. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]