Abstract

Background

Primary cardiac lymphoma is one of the rarest tumours of the heart. It belongs to the extra-nodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. The most common type of this tumour is diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Usually, right atrium and right ventricle are involved. This tumour is fatal unless diagnosed and treated in time. In this article two female patients who were diagnosed with primary cardiac lymphoma and treated at our clinic are described. The first patient went to remission after the treatment, while the second patient died. The goals of this article are to show the difficulties of diagnosing and treating this disease, the role of cardiac surgery in its treatment and to raise awareness of this disease.

Case reports

In this article two female patients who were diagnosed with primary cardiac lymphoma and treated at our clinic are described. The first patient went to remission after the treatment, while the second patient died.

Conclusions

Primary cardiac lymphoma is a very rare disease. At the moment the most effective treatment is chemotherapy. Palliative surgery may be necessary to correct hemodynamics when venous blood flow to the lungs is disturbed.

Keywords: Primary cardiac lymphoma, Heart tumour, Large B cell lymphoma

Background

Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) is a rare malignant disease. A. Johri et al. state that PCL composes just 1.3 % of all cardiac tumours [1]. L. Zhong et al. write that PCL composes only 0.5 % of all extranodal lymphomas [2]. The most common histological type of PCL is large B cell lymphoma [2, 3]. PCL is fatal, unless it is diagnosed and treated in time [4]. Patients usually die within few months after being diagnosed with PCL [5–7]. In this article two patients diagnosed with PCL and treated at our clinic are presented.

Case reports

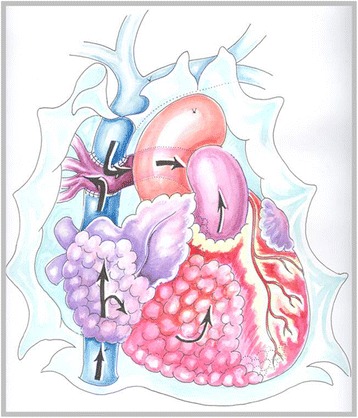

Patient 1, a 48 year old female, who had a history of progressive heart failure, dyspnoea at rest and cyanosis for three weeks prior to hospitalization. The patient had no complaints of fever above 38 C, night sweating or loss of more than 10 % of body weight over a period of six or less (B symptoms). On the day of hospitalization a transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed. An inhomogeneous tumour was found in both atria. It was almost closing the orifice of the tricuspid valve (the diameter of the tricuspid valve orifice was 2.38 cm and the diameter of the part of the tumour closing the orifice was 2.25 cm) and penetrating the left ventricle via the interventricular septum. Complete blood count (CBC) and coagulation profile test (CPT) were within normal limits. The patient was immunocompetent and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) tests were negative. Due to a rapid and severe heart failure an open chest operation was performed, during which a biopsy of the tumour was taken. Fast intra-operative analysis of the specimen revealed that the tumour was malignant. Because the tumour was inoperable and the patient’s hemodynamics was unstable, a decision was made to perform a Fontan procedure as a palliative method in order to stabilize the patient’s condition and to provide time for chemotherapy. The superior vena cava (SVC) was anastomosed to the right pulmonary artery (RPA) (Fig. 1). This way venous blood flow was redirected to the lungs and obstructed right heart was bypassed. After the surgery, the patient’s condition improved. She was extubated on the second day after the surgery. Breathing was spontaneous and arterial blood oxygen saturation (SaO2) was 92 %. A detailed histological exam of the tumour revealed that it was diffuse large B cell lymphoma. There were no evidence of extra-cardiac lymphoma present, thus the final diagnosis was primary cardiac lymphoma. When the patient recovered from the surgery, she decided to continue her chemotherapy treatment at a foreign oncology clinic. To the best of our knowledge, the patient went into remission after chemotherapy.

Fig. 1.

Schema of the procedure performed for the first patient (drawing by O. Barysaite). Black arrows indicate venous blood flow through the right side of the heart

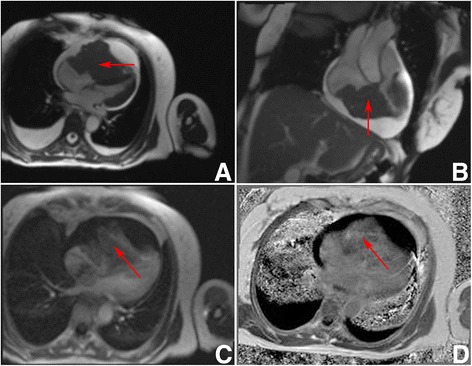

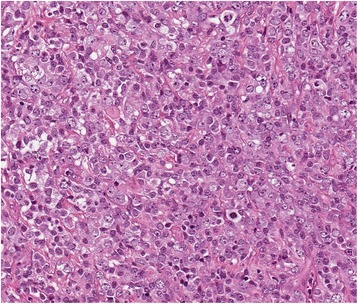

Patient 2, a 64 year old female was diagnosed, with acute nonspecific idiopathic pericarditis, and was referred to our clinic. She had a history of heart failure for six months prior to hospitalisation. On the day of arrival she presented with a decompensated heart failure. Tachypnoea, hepatomegaly and ascites were present. The patient had no complaints regarding the B symptoms. Arterial blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg. CBC and CPT were within normal limits. HIV tests were negative, the patient was immunocompetent. TTE revealed a severe dilatation of the right atrium and right ventricle, a large tumour in the right side of the heart and fluid accumulation in the pericardial sac. In order to specify the diagnosis a pericardiocentesis, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and percutaneous transvenous biopsy (PTVB) of the tumour were performed. The pericardial fluid exam showed that it was transudate with no cells. The MRI revealed a tumour in the right atrium appendage, which was invading the right atrium and ventricle and visceral pericardium. The large tumour (10 x 7.2 x 8 cm) was obstructing the right ventricle, the IVS was pushed towards the left ventricle and slightly interfering with its function (end systolic volume of the LV was 26 ml, end diastolic volume of the LV was 53 ml and LV EF was 52 %, cardiac index was 1. 8 l/min/m2) (Fig. 2). PTVB of the tumour showed mild myocardial fibrosis. 11 days later the patient’s condition started to worsen. An open chest biopsy of the tumour was performed. A fast intra-operative histological exam of the tumour revealed that it was malignant. Because the tumour was inoperable, a decision to perform a Fontan procedure was made. It was intended to stabilise the patient’s hemodynamics. After the surgery the patient’s general condition was satisfactory. She was extubated twelve hours later. Breathing was spontaneous and SaO2 was 90 %. Eight hours later, the patient’s condition began to worsen. She was re-intubated. Asystole developed and cardio-pulmonary resuscitation was initiated. All means to save her life were ineffective. The patient passed away. Detailed histological exam of the tumour revealed that it was a diffuse large B cell lymphoma (immunophenotype: non-germinal centre, CD20-positive, CD10-negative, BCL2-positive, BCL6-positive, MUM1-positive, CD23-negative, CD30-negative, EBER-negative) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Preoperative patient 2 Heart MRI. a 4 chambers GRE view. Hypointensive masses visible in right ventricle, right atrium and right atrial appendage (red arrow). The tumour is obstructing the right ventricle and compressing the interventricular septum, and the left ventricle. b 2 chambers GRE view. Hypointensive masses in the right ventricle and right atrium (red arrow). c 4 chambers view perfusion sequence. Perfusion is seen in the masses (red arrow). d 4 chambers view. Non homogenous gadolinium enhancement is visible (red arrow). All images were taken during diastole

Fig. 3.

Patient 2 tumour histology. Diffuse myocardial infiltration with large B cells (Hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification × 200)

Discussion

There are no unified criteria when this tumour can be called primary cardiac lymphoma. L. Zaharia and P. Gill state that PCL can be diagnosed when the tumour involves the pericardial space and myocardium [8]. On the other hand, Curtsinger et al. state that PCL can only be diagnosed when there is cardiac lymphoma without any other evidence of lymphoma on autopsy [9]. Both of our patients were diagnosed with PCL’s, because histological exams of both tumours showed they were diffuse large B cell lymphomas. And there were no evidence of a tumour present in any other organ of both patients.

PCL is a rare disease. It composes only 1.3 % of all cardiac tumours and 0.5 % of all extranodal lymphomas [1, 2]. The largest review of case-reports and case-series was performed by Petrich et al. It included 197 cases of PCL reports from 1947 – 2009. The authors reported that this disease is more common in the elderly age. The median age of the patients is 63 years), although it ranged from 9 to 90 years (but only 5 patients were younger than 17 years old) [10]. The reported male to female ratio is 2(3):1 [2, 10]. The symptoms of PCL are nonspecific. It can manifest as a heart rhythm disturbance, episodic syncope, vena cava superior syndrome, respiratory distress [2] or even as a restrictive cardiomyopathy [1, 2, 11]. However, the most common symptoms are dyspnoea, constitutional complaints (fever, chills, sweats and weight loss), chest pain, heart failure and pericardial effusion [2, 10]. PCL is more likely to involve the right heart (both atrium and ventricle alike), but there are cases were only the left heart was involved [1, 2, 10, 12–15].

Patients who are suspected of having a PCL must be examined thoroughly. The examination must include echocardiography, heart computed tomography or MRI study, but the final diagnosis can be made only after a histological evaluation of the tumour is obtained. Usually PTVB with transesophageal echocardiographic (TEE) control is used to obtain the specimen [14, 15]. D. Jurkovich et al. has successfully used a combined fluoroscopic imaging and TEE for PTVB [16]. However, in our second case PTVB failed to provide any clinically significant data.

PCL treatment is combined of surgery and chemotherapy. The literature indicates, that when treating with chemotherapy alone 61 % of patients have a remission, while surgery alone has no effect to the outcome [15]. However, surgery is the only method which can provide time for chemotherapy to have a therapeutic effect, especially when hemodynamics is disturbed. If the tumour is localized in the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) and partially or fully occludes the outflow tract, the prognosis is worse [3]. Even in the case of RVOT obstruction surgical treatment does not change the outcome prognosis. As stated by Y. H. Jung et al. it is necessary to diagnose PCL as early as possible, to use intensive treatment with new chemotherapy drugs in order to achieve better outcomes for the patients [3]. K. W. Chen et al. and later A. Habertheuer et al. reported successful recovery of patients after surgical removal of the tumour and postoperative chemotherapy [4, 17].

It was impossible to remove the tumour of either patient. They underwent a surgery because of the obstructed blood flow to the lungs. The main goal of the procedure was to provide patients with time for chemotherapy to have a therapeutic effect. Our first patient survived the procedure and went to remission after chemotherapy. Our second patient, died on the first day after surgery. It is unknown why the outcome of both patients was different. It is possible that the difference in outcomes is related to the elderly age and far more developed initial heart failure of the second patient.

Conclusions

Primary cardiac lymphoma is a very rare disease. At the moment the most effective treatment is chemotherapy. Palliative surgery may be necessary to correct hemodynamics when venous blood flow to the lungs is disturbed.

Consent

Written informed consent for publication could not be obtained from patient 1 and patient’s 2 next of kin despite all reasonable attempts. Every effort has been made to protect the identity of our patients and ensure their anonymity.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to acknowledge Professor Giedrius Uzdavinys, for his help and advice, Dr. Giedre Nogiene, for her dedication and support, and valuable advice, Dr. Tomas Kacergius, for his help dealing with submission of this article, and Vilnius University Faculty of Medicine, our Alma Mater.

Abbreviations

- B symptoms

unexplained fever above 38 °C, night sweating, loss of more than 10 % weight loss over a period of six or less months

- CBC

complete blood count

- CPT

coagulation profile test

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PCL

primary cardiac lymphoma

- PTVB

percutaneous transvenous biopsy

- RPA

right pulmonary artery

- RVOT

right ventricle outflow tract

- SaO2

arterial blood oxygen saturation

- SVC

superior vena cava

- TEE

transesophageal echocardiography

- TTE

transthoracic echocardiography

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the design of the case report and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Karolis Jonavicius, Phone: +370 617 25478, Email: karolismd@gmail.com.

Kestutis Salcius, Email: kestutss@yahoo.com.

Raimundas Meskauskas, Email: raimundas.meskauskas@vpc.lt.

Nomeda Valeviciene, Email: nomeda.valeviciene@santa.lt.

Virgilijus Tarutis, Email: virgilijus.tarutis@santa.lt.

Vytautas Sirvydis, Email: vytautas.sirvydis@santa.lt.

References

- 1.Johri A, Baetz T, Isotalo PA, Nolan RL, Sanfilippo AJ, Ropchan G. Primary cardiac diffuse large B cell lymphoma presenting with superior vena cava syndrome. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:e210–2. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70110-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong L, Yang S, Lei K, Jia Y. Primary cardiac lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Chin-Ger J Clin Oncol. 2013;12:43–5. doi: 10.1007/s10330-012-1095-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung YH, Woo IS, Ko YJ, Lee JH, Lim JW, Han CW. A case of primary cardiac lymphoma showing isolated central nervous system relapse. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14:e31–3. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen K-W, Chang J-H, Yeh S-P, Lu C-R. Primary cardiac B-cell lymphoma with atrioventricular block and paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolla G, Bertero MT, Pastena G, Tartaglia N, Corradi F, Casabona R, et al. Primary lymphoma of the heart. A case report and review of the literature. Leuk Res. 2002;26:117–20. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(01)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nand S, Mullen GM, Lonchyna VA, Moncada R. Primary lymphoma of the heart. Prolonged survival with early systemic therapy in a patient. Cancer. 1991;68:2289–92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911115)68:10<2289::AID-CNCR2820681031>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaharia L, Gill PS. Primary cardiac lymphoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14:142–5. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtsinger CR, Wilson MJ, Yoneda K. Primary cardiac lymphoma. Cancer. 1989;64:521–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890715)64:2<521::AID-CNCR2820640227>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma. Cancer. 2011;117:581–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee GY, Kim WS, Ko Y-H, Choi J-O, Jeon E-S. Primary cardiac lymphoma mimicking infiltrative cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:589–91. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshihara S, Naito M, Tanioka F, Matsunaga M. A case of primary cardiac lymphoma: in vivo imaging and pathologic correlation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013; jet051. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Khuddus MA, Schmalfuss CM, Aranda JM, Pauly DF. Magnetic resonance imaging of primary cardiac lymphoma. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:144–5. doi: 10.1002/clc.20027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burling F, Devlin G, Heald S. Primary cardiac lymphoma diagnosed with transesophageal echocardiography–guided endomyocardial biopsy. Circulation. 2000;101:e179–81. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.17.e179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chin JY, Chung MH, Kim JJ, Lee JH, Kim JH, Maeng IH, et al. Extensive primary cardiac lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;17:141. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2009.17.4.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jurkovich D, de Marchena E, Bilsker M, Fierro-Renoy C, Temple D, Garcia H. Primary cardiac lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous intracardiac biopsy with combined fluoroscopic and transesophageal echocardiographic imaging. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;50:226–33. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-726X(200006)50:2<226::AID-CCD19>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habertheuer A, Ehrlich M, Wiedemann D, Mora B, Rath C, Kocher A. A rare case of primary cardiac B cell lymphoma. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]